Abstract

This study utilized cultivable methods and 16 S amplicon sequencing to compare taxonomic profiles and functional potential of gut bacteria in the scarab beetle, Anomola dimidiata, under cellulose-enriched conditions. Eight culturable cellulolytic gut bacteria were isolated from the midgut and hindgut of the scarab larvae, respectively. 16 S amplicon sequencing evinced that the most represented taxonomic profiles at phylum level in the fermentation chamber and midgut were Bacillota (71.62 and 56.76%), Pseudomonadota (22.66 and 36.89%) and Bacteroidota (2.7 and 2.81%). Bacillota (56.74 and 91.39%) were significantly enriched in the midgut with the addition of cellulose. In contrast, Bacillota and Psedomonadota were significantly enriched in the fermentation chamber. Carbohydrate metabolism was up-regulated in the midgut, while nitrogen and phosphorus metabolism were up-regulated in the fermentation chamber, suggesting these symbionts’ possible metabolic roles to the host. An analysis of total cellulases as well as amplicon sequence variants indicated that the gut bacteria belonging to Acinetobacter, Bacillus, Brucella, Brevibacillus, Enterobacter, Lysinibacillus and Paenibacillus are involved in nutrition provisioning. These results have provided additional insights into the gut bacteria associated with cellulose digestion in A. dimidiata and created a platform for bioprospecting novel isolates to produce biomolecules for biotechnological use, besides identifying eco-friendly targets for its management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Insects harbour a complex community of microbes, some on their exoskeletons, in the hemocoel, gut, and within specialized cells. These microbial associations range from mutualistic to pathogenic. The role of symbiotic microbiomes has lately received much attention as they have been linked to key aspects of host physiology, including nutrition, reproduction, fitness, defence, and endowing the hosts with the phenotypic ability to withstand environmental changes1,2,3. Phytophagous insects, in particular, possess the plasticity to exploit diverse diets. This, in part, has been attributed to their gut microbial symbionts, which play essential roles, and some are involved in lignocellulosic digestion4,5. Despite surviving on plant diets and evidence of many carbohydrolytic-related processes in insects, knowledge of their functional profiles and the related microbial groups still needs to be made available. The gut of insects is reported to harbour unique microflora. Their gut morphologies and physiologies have evolved to provide the host with an array of fitnes advantages, for instance, through hydrolysis of otherwise non-digestible food material such as cellulose6,7.

Scarab beetles are a family of insects belonging to the order Coleoptera. They can degrade plant material, including roots and organic matter9. Scarabs are also economic insect pests of most crops, where the grubs are root feeders and their adult beetles feed on leaves10. The feeding ability of scarabs appears to differ significantly, which is attributed to their symbiotic association with gut bacteria, which may be shaping their plasticity11. Recent advances in metagenomics research have shown that microbial associations with insects are linked to developmental processes, digestion and metabolism, and defence12. Thus, the guts of these saprophagous macroinvertebrates are involved in transforming organic matter and nitrogen and carbon cycling in terrestrial environments. The hindgut of scarabs, especially between the pyloric sphincter and the rectum, is a complex, enlarged chamber-like structure believed to be the significant site for digestion. This modified chamber is lined with cuticles and covered with lobe-like structures harbouring many microbes reported to aid in the digestion of plant biomass11.

Cellulose digestion efficiency, estimated up to 65% of the scarab diet, has been attributed to the microbes within the scarab larval intestinal tract, which produce multiple enzymes responsible for cellulose digestion12. With this background, this investigation was conducted to profile the diversity of gut bacteria associated with the root grub, A. dimidiata, prevalent in northeastern India, through metagenomic sequencing and analysis of the 16 S ribosomal RNA gene. In addition, we enriched cellulolytic gut microbes from the midgut and fermentation chamber of A. dimidiata by culturing the homogenates from these compartments in minimal medium supplemented with a cellulose substrate for six weeks. In particular, this work focused on profiling the diversity of gut bacteria in the different gut sections of the scarable beetle digestive system under a cellulose-enriched microenvironment with an emphasis on understanding the variation of predominant cellulolytic gut microbiota of A. dimidiata across the digestive system. The profiling of gut bacteria and their function would raise the possibility of utilizing such information to enhance the suitability of control of economically important pests such as A. dimidiata by identifying possible new targets for pest management in addition to bioprospecting novel isolates and genes for the production of enzymes of biotechnological use.

Materials and methods

Insect culture

Third instar larvae of A. dimidiata, was collected from a potato field at the Indian Council for Agricultural Research (ICAR) regional station, the Central Potato Research Station, at latitude 29° 4′ N and longitude 77° 46′ E, Modipuram, UP, India. The insects were transferred to the laboratory in aerated plastic jars with field soil (with potato slices) and maintained under a regime of 16:8 h light and dark period with rearing temperature of 26 ± 1 °C and 70% relative humidity (RH) at the Division of Entomology, IARI, Pusa Campus; New Delhi, India until they were dissected. The larvae were starved for 24 h to clear the gut before dissection.

Gut dissection

The midgut (MG) and fermentation chamber (FC) compartments were used for metagenomics analysis of gut bacteria, and five healthy larvae of approximately the same size were used. Twenty-four hour-starved insects were placed in Petri dishes and immobilized by briefly placing them at − 20 °C freezer. The insects were then surface sterilized by immersing them for 60 s in 70% ethanol, followed by rinsing in sterile double-distilled water, before being placed on a dissecting wax plate that had been surface sterilized by wiping with 70% ethanol. The dissection was done by using sterile microscissors in a lamina flow, and the guts of the insects were gently removed and partitioned into midgut and fermentation chamber compartments and placed in a sterile 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube containing 0.85% NaCl. Two sets of samples were prepared from each gut section, as follows: The first set comprised direct extraction of total genomic DNA from the midgut and fermentation chamber (to cutter for both cultivable and uncultivable bacteria) designated as midgut-metagenome (MGM) and fermentation chamber-metagenome (FCM).

Enrichment of cellulose-degrading gut bacteria

The root grubs survive entirely on cellulosic diets; as such, we were interested in enriching the metagenome diversity of cellulolytic gut bacteria from these compartments. To enrich cellulose-degrading gut bacteria, twenty-four-hour-starved (to clear the gut before dissection), healthy individuals were rinsed in double-distilled water for 30 s, followed by 70% (v/v) ethanol for 60 s and again rinsed in double-distilled water for 30 s to remove the disinfectant. The sterilized larvae were dissected using sterile micro-scissors under aseptic conditions to extract the gut. The gut compartments were rinsed in sterilized 0.85% sodium chloride (NaCl) and homogenized in sterile 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes containing 0.85% NaCl saline buffer using a sterile glass homogenizer, and 200 µl of the gut homogenate from each section was inoculated in sterile plastic vials containing 10 ml of autoclaved minimal salts medium with the following composition in grams per litre: NaNO3, 2 g; K2HPO4, 0.5 g; MgSO4·7H2O, 0.02 g; MnSO4·7H2O, 0.02 g; FeSO4·7H20, 0.02 g; and CaCl2·2H2O, 5 g, containing single sterilized 1 × 6 cm Whatman No. 1 filter paper strips (~ 50 mg). The inoculated media was incubated at 37 °C for 6 weeks or until the filter paper strips were visibly degraded, indicating the presence of cellulose-degrading bacteria. A control treatment was included, which contained only autoclaved minimal salt medium with filter paper without insect gut homogenates. After visible digestion of filter paper, the digestome was inoculated in nutrient broth for overnight growth, followed by DNA extraction, designated as midgut filter paper degradation (MGP) and fermentation chamber filter paper degradation (FCP) metagenomic samples.

Isolation of culturable cellulose-degrading gut bacteria

Additionally, an attempt was made to isolate culturable cellulose-degrading bacteria from the midgut(MG), fermentation chamber(FC), and hindgut(hg) of A. dimidiata. After visible degradation of filter paper strips, 100 µl of suspension from each insect gut compartment was serially diluted (8-fold) and inoculated on minimal salt agar medium supplemented with carbon methyl cellulose (CMC) as follows: CMC 1.0%, yeast extracts 0.025%, ammonium sulphate 0.05%, calcium chloride 0.05%, monobasic potassium phosphate 0.01%, dibasic potassium phosphate 0.01%, and agar 1.5%, pH 7.0 as described by Huang and Zhang13. The inoculated plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24–48 h. The bacterial colonies were differentiated based on their colour, size, and morphology, and a single representative isolate of each morphotype was purified by streaking on corresponding agar plates repeatedly until the purity of each culture was obtained. The individual purified strains were grown in nutrient broth and maintained in glycerol stock at − 80 °C. The glycerol stock was prepared with 300 µl of 50% glycerol and 700 µl of broth bacterial culture to attain an end concentration of 10–15%.

PCR amplification of the 16 S rRNA of culturable cellulose-degrading bacteria

Distinct representative purified bacteria colonies were chosen for identification based on 16 S rRNA gene sequence analyses. Individually purified bacterial isolates were grown in nutrient broth for 24 h at 37 °C. After 24 h of growth, the broth cultures were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm to separate the pellet and supernatant. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was used for DNA extraction using a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method. The 16 S rRNA gene sequence of each isolate was amplified by PCR using BioLine Master Mix and eubacterial primers 27 F-‘AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG’ and 1492 R-‘AAGGAGGTGATCCAGCCGCA’. Each reaction contained approximately 50 ng of DNA, 25 µl of Master Mix (2X), and 0.5 mM of each primer. The PCR was carried out in a Bio-Rad C1000-thermal cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Berkeley, CA, USA) as follows: one cycle at 94 °C for 5 min, 35 cycles at 94 °C for 1 min, 52 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min 40 s, followed by 72 °C for 10 min and 4 °C forever. PCR products were examined by electrophoresis in a 1.2% agarose gel, and bands were visualized by staining with ethidium bromide. The gels were run at 100 V for 1.0 h in TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM ethylene-diamine-tetra-acetic acid (EDTA); pH 7.4). Gels were visualized under UV in the Gel Documentation System of the Alpha ImagerTM gel imaging system (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA, USA).

Bioinformatics analysis of culturable gut bacteria

The 16 S rRNA PCR product sequencing was outsourced from a private laboratory (AgriGenome Labs Pvt. Ltd., India). The gene sequences were assembled and aligned using BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor V. 7.0.5.3 and compared with the EzBioCloud 16 S database search (http://www.help.ezbiocloud.net). A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbour-joining method with Kimura’s two-parameter correction9. To calculate the support for each clade, bootstrap analysis was performed with 1000 replications10.

Cellulolytic enzyme production

Individual bacterial cultures isolated from degraded filter paper homogenates were inoculated into a production medium according to Lisdiyant et al.16 and incubated at 37 °C for 36 h. After incubation, the crude enzyme produced was harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The entire digestome from each gut compartment cell-free extract was also assayed for cellulolytic activity.

Protein determination

Protein concentration was measured according to the method of Bradford17, using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Total cellulase activity assay

The enzyme activity of crude cellulase for the three glycoside enzymes, i.e., exoglucanase, endoglucanase, and β-glucosidase activity, was estimated by using different commercially available substrates, such as carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), cellobiose, and filter paper. The cellulase activity was assayed by estimating the activities of three glycoside enzymes, i.e. exoglucanase (filter paper as substrate), endoglucanase (CMC as substrate) and β-glucosidase (cellobiose as substrate). The assay was conducted for eight individual cellulose-degrading bacteria and whole homogenate samples. For both categories, the assays beginning with enzyme production and reading absorbance at 540 nm were repeated three times. Each absorbance reading involved three technical replicates, which were then averaged to obtain a mean value for that treatment. Normality was assessed by generating a Gaussian distribution (sampling distribution) and using the Q-Q plot function (quantile-quantile plot) to compare the theoretical residuals of a perfect homoscedastic model with the actual residuals.

The amount of reducing sugars released was estimated using the DNSA method by Miller18. The amount of glucose produced was calculated using an established glucose standard curve, and the values obtained were used to determine enzyme activity. The amount of reducing specific enzyme activity was calculated using the following formula:

Endoglucanase activity was expressed in terms of units. One unit is the amount of enzyme releasing 1 µmol of reducing sugar from carboxymethyl cellulose per ml per minute. One unit of cellobiose activity (β-glucosidase) was defined as the amount of enzyme released in 1 µmol of reducing sugars from cellobiose per ml per minute. Exoglucanase activity was determined using a method described by Zhang et al.19. One unit is the amount of enzyme in the culture filtrate releasing 1 µmol of reducing sugars from filter paper per minute.

16 S rRNA gene sequencing

The MG and FC of the 3rd instar white grab larvae were used for analysis. Five healthy larvae of approximately the same size were used. Five larvae were used for each gut section, and dissection was carried out as described earlier. Total genomic DNA to be used for analysis was pooled as follows: DNA directly extracted from the MG and FC (both cultivable and uncultivable bacteria) and 24-h nutrient broth enriched growth using homogenates from the MG and FC was done using the DNeasy Power Kit (Qiagen, USA) using the five pooled samples from the respective gut compartments mentioned earlier. The integrity of DNA was checked by gel electrophoresis and concentration and purity by Qubit Fluorimeter (V.3.0). The V3-V4 region of 16 S rRNA was amplified using a specific V3 forward primer (5′→ CCTACGGGNBGCASCAG→3′) and a V4 reverse primer (5′→ GACTACNVGGGTATCTAATCC→3′). The amplified product was checked on 2% agarose gel, and gel purification was done to remove non-specific amplifications. Five ng of amplified product was used for library preparation using NEBNext Ultra DNA library preparation kit (New England Biolabs Inc., Ipswich, Massachusetts, USA). The library quantification and quality estimation were done in Agilent 2200 TapeStation. The prepared library was then sequenced in Illumina HiSeq 2500 with 2*250 chemistry cycles, with each sample replicated twice.

Raw sequence data processing

Original data acquired by high-throughput sequencing, recorded in image files, was first transformed into sequence reads by base calling using the CASSAVA software. The resulting corresponding sequencing quality information was stored as a FASTQ file. The FastQC software server (version 0.11.8) was used to check the base quality score distribution, sequence quality score distribution, average base content per read, and GC distribution in the reads. Illumina adapters (AGATCGGAAGAGC) were removed using the trim galore (version 0.4.1), which is a wrapper script to automate quality and adapter trimming as well as quality control, whereas PANDASeq (version 2.11) was used for pair-end assembly of the reads. Chimeric sequences were eliminated by using the Denovo UCHIME programme (http://www.drive5.com/usearch/manual/uchime_algo.html) with the ‘Gold’ reference database (http://drive5.com/uchime/uchime_download.html)20,21.

Taxonomic analysis

High-quality, unassembled reads of the four metagenomic samples were uploaded into the Metagenomics Rapid Annotation using the Subsystem Technology (MG-RAST) server22. Taxonomic profiles of the metagenomic reads were assigned with a maximum e-value of 1e−05, a minimum of 60%, and a minimum alignment length of 15 bp. The statistical analysis of the different taxonomic levels generated using MG-RAST was done using the Statistical Analyses of Metagenomic Profile (STAMP) software. The significance between proportions in the taxonomic distribution of the samples was measured using Fisher’s exact two-sided test with the Newcombe-Wilson confidence interval method. Functional analysis of marker gene sequences was performed using the SEED subsystems annotation in the MG-RAST, with a maximum e-value of 1e−05, a minimum identity of 60%, and a minimum alignment length of 15 bp. The cultivable filter paper-degrading bacteria were subjected to PICRUSt2 to profile their involvement in various metabolic pathways, including starch, sucrose, and fructose metabolism.

Data analysis and statistics

Analyzable data (cellulolytic indices, among others) were subjected to descriptive statistics and analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SAS software. The normality of total cellulase data was checked by generating a Gaussian distribution using a qplot function. Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) was used to determine differences between each factor at P = 0.05. Pictorial representation of overall workflow and result is depicted in Suppl. File 1; Fig. S4.

Results

This research focused on profiling gut bacteria inhabiting the midgut and fermentation chamber of A. dimidiata, zeroing in on cellulose degradation employing cultivable techniques and metagenomic analysis. The filter paper degradation assay showed that A. dimidiata harbours cellulolytic gut bacteria. Filter paper degradation occurred in all the three gut sections; however, it was faster in the hindgut and fermentation chamber, reaching 90% within fifteen days of incubation, as shown in Supplementary File 1 and Table S1. The pictorial representation of the before and after incubation status of filter paper strips (cellulose substrate), including the untreated check, is presented in Fig. 1a,b.

(a) Un degraded filter paper before incubation of gut homogenates prepared from the different compartments of A. dimidiata larvae; and (b) filter paper degradation after six weeks of incubation. (c) The phylogenetic tree illustrates the evolutionary relationships among gut bacteria isolates from the scarab midgut, fermentation chamber, and hindgut. Next to the branches is the percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates). Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7.

After the visible degradation of filter paper, an attempt was made to isolate the cellulolytic gut bacteria. The present study isolated eight cellulose-degrading gut bacteria from A. dimidiata. The gut bacterial isolate sequences were identified at the genus level by aligning them with their closest relatives in the EzBioCloud 16 S database (https://www.ezbiocloud.net)23. Sequence analysis revealed that the culturable bacterial isolates belonged to the genera Bacillus, Brucella, Enterobacter, Lysinibacillus, and Ochrobactrum. All isolates showed 99–100% nucleotide homology with their closest bacterial strains (Table 1).

Phylogenetic analysis of filter paper degrading gut bacteria isolates from A. dimidiata

The phylogenetic tree of 16 S rDNA gene sequences of cellulose-degrading gut bacteria is provided in Fig. 1c. While isolates MT259172 and MT259179 belonging to Bacillota clustered closely together, suggesting a closer evolutionary relationship, four isolates, namely MT259178, MT259170, MT259171 and MT259173, formed separate branches, indicating that they were distantly related. However, it was surprising to note that isolates MT259174 and MT259177 belonging to different genera clustering together with 78 bootstraps, suggesting some similarities.

Cellulolytic activity of enriched digestome fluids from A. dimidiata

The results of cellulolytic activity from the cell-free cultures indicated that significant activity of endoglucanase (P = 0.0109) and exoglucanase (P = 0.0173) was found in the different gut compartments of A. dimidiata. A Tukey comparison of the glycoside enzymes from A. dimidiata indicated that endoglucanase and exoglucanase activity were significantly higher in the hindgut > midgut > fermentation chamber. The β-glucosidase was considerably higher (P ≤ 0.0001) in the fermentation chamber > midgut > hindgut (Fig. 2a,b; Supplementary File 1; Table S2).

(a) Cellulolytic activity of enriched cell-free culture digestome fluids from A. dimidiata. Means with at least one letter common are not statistically significant using TUKEY’s Honest Significant Difference. (b) Cellulolytic activity (mean U/mg) of cellulose-degrading gut bacteria from A. dimidiata. Means with at least one letter common are not statistically significant using TUKEY’s honest significant difference.

Cellulolytic activity of individual culturable filter paper degrading bacterial isolates

The individual bacterial strains from A. dimidiata were assayed for their ability to produce the three cellulolytic enzymes required to completely degrade cellulose (Fig. 2b and Supplementary File 1; Table S3). Significant differences were found between cellulose-degrading gut bacterial isolates on endoglucanase (P = < 0.0001), Exoglucanase (P = < 0.0001), and β-glucosidase (P = < 0.0001) activity. The endoglucanase, exoglucanase, and β-glucosidase activities ranged from 0.37 to 1.63, 0.63 to 1.27, and 2.74 to 10.46 U/mg in A. dimidiata. A Tukey comparison of enzyme activity means from A. dimidiata showed that significantly higher endoglucanase activity was found in isolates WG-MG4-FP and WG-FC4-FP. In contrast, substantially higher exoglucanase and β-glucosidase activity was found in isolates WG-FC4-FP, WG-HG1-FP, and WG-GH3-FP, respectively.

Bacterial 16 S rRNA gene sequence reads

Scarab beetle larval DNA (MG and FC) was sequenced using the V3-V4 16 S region using Illumina HiSeq 2500. After the quality control using FastQC, the fermentation chamber metagenome sample (FCM) yielded the most reads. In contrast, the FCP (filter paper enriched) yielded the fewest reads. The average gene sequence length was 301 nt. 147,354, 128,074, 139,930, and 303,015 were identified from the FCP, MGP, FCM, and MGM samples, respectively (Supplementary File 1; Table S4). All the sequence data were deposited in the Sequence Research Archive (SRA) in the NCBI database under the Bioproject accession number PRJNA647896.

Identifying gut bacteria by 16 S rRNA gene sequencing in a normal midgut and fermentation chamber of A. dimidiata

The most represented taxonomic profiles at the domain level in both samples were Bacteria (98.20 and 98.82%), followed by Eukaryota (1.74 and 1.09%) and Archaea (0.05 and 0.09%). However, the midgut harboured significantly more bacteria compared to the fermentation chamber. Bacillota (71.62 and 56.76%), Pseudomonadota (22.66 and 36.89%), and Bacteroidota (2.7 and 2.81%) were the most abundant phyla in the two samples. However, both metagenomes differed significantly, as Bacillota and Bacteroidota were more abundant in the fermentation chamber. At the same time, Proteobacteria were substantially more abundant in the midgut (Supplementary File 1; Table S5).

Orders Bacillales (45.29 and 46%), Clostridiales (26.1 and 10.12%), Enterobacteriales (21.88 and 30.96%), Bacteroidales (1.79 and 1.61%), and Pseudomonadales (5.23% in MGM) were the most abundant in the two samples. However, Clostridiales were significantly more abundant in FCM than Enterobacteriales, which were more abundant in MGM.

The most abundant genera in both samples were Clostridium (52.15 and 10.67%), Bacillus (20.58 and 1.51%), Paenibacillus (6.47-FCM), Lysinibacillus (2.73 and 1.51%), Klebsiella (57.18%-MGM), Pseudomonas (9.40%-MGM), Acinetobacter (1.98%-MGM), and Prevotella (1.88%-MGM). However, Clostridium, Bacillus, and Lysinibacillus were significantly more prevalent in the fermentation chamber, in contrast with the prevalence of Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, and Acinetobacter, which were substantially more abundant in the midgut.

Analysis of gut bacteria variation in a normal and filter paper enriched midgut of A. dimidiata

Gut homogenates from freshly dissected midgut and fermentation chambers of A. dimidiata were inoculated in a minimal medium supplemented with filter paper as a cellulose substrate. This aimed to enrich only cellulose degraders, as this insect mainly survives on cellulosic food diets. The results of a comparative analysis of a normal and cellulose-enriched midgut of A. dimidiata are provided in Fig. 3a–c. Gut bacteria belonging to Bacillota (56.74 and 91.39%) were significantly enriched in the midgut of the filter paper-enriched sample compared to a normal sample. The abundance of Pseudomonadota (36.89 and 1.49%) was significantly reduced. At the genus level, there was a significant increase in bacteria belonging to Bacillus (0.1 and 48.7%) and Paenibacillus (0 and 25.8%) in the filter paper-enriched midgut compared to the normal midgut sample (Fig. 3a).

(a) A Venn diagram analysis of normal and enriched gut sections highlights cellulolytic gut bacteria enriched under cellulose enriched and those unique to particular gut sections and those shared between sections. Different colours represent the different gut sections. MGM normal midgut, MGP cellulose enriched midgut, FCM normal fermentation chamber, FCP cellulose enriched fermentation chamber. (b) Heat map analysis of the abundance distribution of bacterial phyla associated with A. dimidiata larvae. The taxonomic relationship of the bacterial species is shown in the rows. In contrast, the clustering of the phyla is shown in the columns. Higher intensities of the colour indicate higher abundances of the phyla (Group 1 = cellulose enriched; Group 2 = normal guts). (c) Heat map analysis of the abundance distribution of bacterial genera associated with A. dimidiata larvae. The taxonomic relationship of the bacterial species is shown in the rows. In contrast, the clustering of the genera is shown in the columns. Higher intensities of the colour indicate higher abundances of the genera. (Group 1 = cellulose enriched; Group 2 = normal guts).

Comparative analysis of gut bacteria in a normal and filter paper enriched fermentation chamber ofA. dimidiata

At the phylum level, bacteria belonging to Bacillota and Pseudomonadota were significantly enriched in the fermentation chamber compartment with a cellulose substrate (filter paper) compared to a normal FC (Fig. 3b). Genera Bacillus (1.1 and 12.2%), Acinetobacter (1.5 and 18.9% FCP), and Brevibacillus (0 and 10.7% FCP) were significantly enriched in the fermentation chamber with the addition of cellulose compared with a standard sample (Fig. 3b). Bacterial isolates belonging to Acinetobacter, Bacillus, Brevibacillus, Lysinibacillus, Paenibacillus and Pseudomonus appear to be the core gut symbionts in A. dimidiata as they were enriched in either the midgut or fermentation, some in normal samples while others after addition of a cellulose substrate (Fig. 3c). The genus Disnonomus was present in both the normal midgut and fermentation chamber. At the same time, Ochromobacterum appeared to be enriched only with a cellulose substrate. Brevibacillus was unique to the fermentation chamber. A detailed list of the most abundant amplicon sequence variants in both enriched and normal samples across gut compartments is provided in Supplementary File S2.

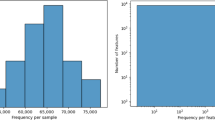

Diversity analysis

Community richness is estimated by rarefaction and provides multiple metrics for measuring microbial alpha diversity, including Shannon index analysis to account for differences in sample sizes. The rarefaction curve (Fig. 4) showed that the microbial communities of all the samples from both Group 1 (FCP and MGP) and Group 2 (FCM and MGM) had good sequence coverage, with the reads being rarefied to 20,000 and 18,000, respectively. No significant differences in changes in alpha-diversity indices were observed between the two groups on the Shannon and Simpson indices (which incorporate evenness and species richness), Chao1 (estimates species richness), Evenness, and Richness, suggesting that the taxonomic diversity of the gut bacteria of the groups was similar.

Beta-diversity analysis

Multivariate statistics are powerful techniques that can identify complex associations between community composition and multiple explanatory variables, for example, by the multivariate methods of principal component analysis (PCA) and redundancy analysis (RDA). The multivariate analysis tool was applied to measure beta diversity to sequences using the abundance distance-based measurement, Bray–Curtis (compositional dissimilarity based on counts), by generating the principal component analysis (PCoA) and redundancy analysis (RDA). The PCoA measurement in the two groups indicated that there was an emerging pattern of separation between samples of group two (FCM and MGM) as compared to group one (FCP and MGP) (Fig. 5a), suggesting that there were more dissimilar communities in group two compared to group one. Similarly, this pattern was also observed in the Bray–Curtis distance PCoA and RDA analysis of the samples, indicating that the distance between the groups was consistent with the abovementioned results. These results underscore the fact that for group 1, only those that were enriched could degrade cellulose. In contrast, group 2 had a range of bacterial communities with cellulose degrading and non-cellulose degrading bacteria.

Comparative analysis of functional features between normal and filter paper-enriched gut sections

The study also conducted a functional profile to unravel the likely bacterial involvement in digestion and host nutrition. The functional profile generated with MG-RAST indicated that there were significant differences in proportions for subsystems at level 1 between the FC and MG of A. dimidiata larvae (considering p < 0.05 and differences of at least 1% and a twofold ratio between proportions) (Suppl. File 1; Fig. S1).

The functional analysis uncovered that the majority of bacterial groups within the scarab gut (~ 70%) may be involved in metabolism, including carbohydrates and nitrogen metabolism (Fig. 5b). Carbohydrates and cell wall and capsule subsystems were the most abundant functional categories in the midgut compared with protein metabolism, virulence, disease and defence, motility and chemotaxis, and amino acids and derivatives functional categories, which were more abundant in the fermentation chamber. A comparative analysis of a normal and a cellulose-enriched midgut showed a significant increase in carbohydrate metabolism, cell wall, and capsule functional categories in MGP compared with MGM, as depicted in Fig. 6a,b and Supplementary File 1; Fig. S2). There was a similar trend in the enriched fermentation chamber, as shown in Fig. 7a,b, in addition to a significant increase in iron acquisition and metabolism, nitrogen and phosphorus metabolism (Suppl. File 1; Figs. S2 and S3).

(a) Starch and sucrose metabolism pathways in normal midgut. The pathway points highlighted in green show the enzyme with which the gut bacteria of scarab beetles may supplement the endogenous metabolism. (b) Starch and sucrose metabolism pathways in enriched midgut. The pathway points highlighted in green show the enzyme with which the gut bacteria of scarab beetles may supplement the endogenous metabolism.

(a) Starch and sucrose metabolism pathways in normal fermentation chamber midgut. The pathway points highlighted in green show the enzyme with which the gut bacteria of scarab beetles may supplement the endogenous metabolism. (b) Starch and sucrose metabolism pathways in enriched fermentation chamber midgut. The pathway points highlighted in green show the enzyme with which the gut bacteria of scarab beetles may supplement the endogenous metabolism.

Discussion

In this study, we utilized Sanger sequencing and metagenomics analysis of the bacterial 16 S rRNA gene to characterize microbial communities’ variation and functional profiles associated with the standard and cellulose-enriched midgut and fermentation chamber of A. dimidiata larvae. Gut bacteria belonging to Bacillota were most abundant in the fermentation chamber. At the same time, Pseudomonadota and Bacteroidota were abundant in the midgut. The genera Clostridium, Bacillus, and Parabacteroides were dominant in the fermentation chamber. At the same time, Lysinibacillus, Klebsiella, and Pseudomonas were more prevalent in the midgut.

Variations in relative abundance were found among the dominant bacterial groups between the gut compartments. This was true for Bacillota, which was abundant in the fermentation chamber. In contrast, bacteria belonging to Pseudomonadota were abundant in the midgut. We attribute this to the different physicochemical and morphological modifications of the gut and the fact that these bacterial symbionts may be enriched differently in the different gut compartments based on their symbiotic roles to the host. Bacterial communities belonging to Bacillus, Clostridium, Lysinibacillus, Klebsiella, and Pseudomonas were the most abundant genera of the Bacillota and Pseudomonadota phylum. In an earlier study using cultivable methods, we also found that Bacillota (62.5%) were the dominant culturable gut bacteria, followed by Pseudomonadota (37.5%) in A. dimidiata18.

Earlier studies on metagenomic analysis of gut microbiome in scarab beetles have reported the dominance of Bacillus and Clostridium4, and taxonomic units belonging to Pseudomonadota, Bacteroidota and Bacillota have been reported as dominant microbiota in the hindgut of H. parallela, larva, another species of white grubs commonly found in China through culture-dependent and independent studies11. Other studies have reported Pseudomonadota as the most abundant group in gut communities of insects such as Dendroctonus rhizophagus (Curculionidae: Scolytinae), Harpalus pensylvanicus (Coleoptera: Carabidae), Schistocerca gregaria (Orthoptera: Acrididae), and B. dorsalis24,25,26. These variations may be due to habitat and diet differences and differences in culturing and sequencing approaches for the bacterial 16 S rRNA gene. However, it is apparent in all these reports that bacterial symbionts belonging to either Bacillota or Pseudomonadota dominate the guts of most insects. This suggests these bacterial communities play significant symbiotic roles in these host insects.

Functional annotation of gut bacteria and their metabolic pathways in the midgut and fermentation chamber of A. dimidiata suggest that the gut bacteria associated with the midgut were mainly involved in carbohydrate and sucrose metabolism. In contrast, those in the fermentation chamber are involved in protein metabolism, nitrogen/amino acid derivative activities, virulence, disease, and defence functions. When enriched with a cellulose substrate, carbohydrate metabolism was up-regulated in the midgut. In contrast, nitrogen metabolism, iron acquisition, metabolism, and phosphorus metabolism functions were more pronounced in the fermentation chamber, suggesting the possible roles these microbes offer in these gut segments.

The scarab beetle larvae survive solely on lignocellulosic food diets such as plant roots and other nutritionally low organic matter11. This suggests they may possess symbiotic gut bacteria that can degrade cellulose. The ability to degrade filter paper is considered an indication of the presence of cellulolytic gut bacteria. The results from filter paper degradation assays suggest that A. dimidiata harbours cellulolytic gut bacteria. Varying levels of filter paper digestion were achieved among the gut homogenates, indicating that the gut compartments may harbour localized microbes with different levels of cellulolytic robustness. This was also evidenced in the cellulolytic activity of gut bacteria in cell-free secretome analysis from the different gut compartments. Culturable cellulose-degrading bacteria isolated from the midgut and fermentation chamber belonged to the genera Bacillus, Enterobacter, Lysinibacillus, and Ochrobactrum.

The analysis of 16 S rRNA gene sequencing also found that the above groups were highly enriched either in the midgut or fermentation chamber, suggesting that they are involved in cellulose digestion. An evolutionary relationship of the culturable cellulose-degrading bacteria suggests that some isolates were very closely related. In contrast, others formed separate branches, indicating they are distantly related and could be unique isolates. In an earlier study of culturable gut bacteria, it was found that most isolates belonging to Bacillus, Pseudomonas, and Enterobacter had cellulolytic, lipolytic, and nitrate reductase activity18. Previous studies have reported the presence of several hemicellulolytic, endo-xylanase, and beta-xylosidase bacterial strains from the gut of scarab pests4,25. Bacteria belonging to these genera have also been implicated in cellulolytic activities in other insects26.

Cellulose digestion requires a synergistic action of exoglucanase, endoglucanase, and β-glucosidases17,27. Endoglucanases attack randomly along a cellulose molecule and dissociate from it after making a few cleaves. Exoglucanases, on the other hand, have an active site inside a tunnel and remove subunits at both reducing and non-reducing ends of cellulose, releasing either cellobiose or glucose and β-glucosidase completely hydrolyze cellobiose to glucose28,29. A comparative analysis of the secretome cellulolytic activity from the different compartments suggested that the gut bacteria were able to produce the three glycoside enzymes required for complete hydrolysis of cellulose; however, the varying levels of the cellulolytic proteins seem to be dependent on the type of bacteria localized in that gut compartment.

Scarab beetles are economic pests of most crops (cereals, groundnuts, pulses, sugarcane, plantation crops, turf, pastures, and solanaceous crops) in many parts of the world where the grubs feed roots rich in hemicellulose and lignocellulose10,11. Since gut bacteria can decompose cellulose and lignin, they may degrade the roots and organic matter of plants they survive in the soil28. The findings suggest these microbial groups may be essential gut symbionts in A. dimidiata. Insects deploy diverse mechanisms that enable them to survive in diverse ecological niches. Key to these are enzymes, which can be produced by the insects, complemented by microbial associations that are used as digestive helpers, which give the insects the plasticity to survive in extreme environments29.

The role of microbial associations in insects, particularly their beneficial aspect, has gained much attention lately. It has been linked to critical aspects of host physiology by supporting host fitness with roles ranging from energy metabolism and resistance to unfavourable conditions to shaping the immune system1,34,35. Many strategies currently utilize microbe-based enzymes to degrade plant biomass for bioenergy production. Scarab larvae have been suggested as a good model as they consume cellulose from multiple sources and can extract nutrients and energy from these sources with the help of endogenous enzymes complimented with proteinases and cellulolytic enzymes produced by symbiotic microbes. Because of the wide diversity of microbes in the gut of scarab larvae, which are involved in lignocellulosic degradation through enzymatic and fermentative processes, scarabs stand to assist the biofuel industries in prospecting for new sources of efficient enzymes of microbial origin36.

Conclusion

As white grubs predominantly survive on cellulosic food diets, this study profiled the diversity of gut bacteria in a cellulose-enrichment microenvironment. Deploying 16 S rRNA gene sequencing, coupled with a culture-dependent approach, helped to identify beneficial bacterial groups that are capable of degrading cellulose. Furthermore, the pathways unravelled, especially for starch and sucrose, as well as nitrogen metabolism, have enabled the identification of unique cellulolytic or nitrogen-fixing bacteria having high enzymatic activity, such as those belonging to the genera Bacillus, Enterobacter, Lysinibacillus and Paenibacillus. Further characterization of these bacterial isolates will lead to the identification of novel genes that would be utilized in bioprocesses such as biofuel production and the production of actual biomolecules such as cellulases in composting of crop residues for effective nitrogen recycling besides other biotechnological uses. In addition, the primary symbionts in the gut can be targeted by way of symbiont disruption as an eco-friendly option for sustainable pest management.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article (and its Supplementary Information files). The details of sequences of gut bacteria generated in this study have been deposited with NCBI Nucleotide Database vide accession numbers: MT259170, MT259177, MT259171, MT259172, MT259173, MT259174, MT259178, MT259179. 16s amplicon sequencing data is submitted to NCBI under bioproject id: PRJNA647896.

References

Stathopoulou, P. et al. Irradiation effect on the structure of bacterial communities associated with the oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis. Entomol. Exp. Appl.167 (3), 209–219 (2019).

Rausch, P. et al. Comparative analysis of amplicon and metagenomic sequencing methods reveals key features in the evolution of animal metaorganisms. Microbiome. 7 (1), 1–19 (2019).

Gouda, M. R., Kumaranag, K. M., Ramakrishnan, B. & Subramanian, S. Deciphering the complex interplay between gut microbiota and crop residue breakdown in forager and hive bees (Apis mellifera L). Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 100233 (2024).

Engel, P. & Moran, N. A. The gut microbiota of insects–diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol. Rev.37, 699–735 (2013).

Shi, W. et al. Comparative genomic analysis of the endosymbionts of herbivorous insects reveals eco-environmental adaptations: biotechnology applications. PLoS Genet.9, 1 (2013).

Mereghetti, V., Chouaia, B. & Montagna, M. New insights into the microbiota of moth pests. Int. J. Mol. Sci.18, 2450 (2017).

Mathews, S. L. et al. Public questions spur the discovery of new bacterial species associated with lignin bioconversion of industrial waste. R Soc. Open. Sci. 6, 180748 (2019).

Huang, S. & Zhang, H. The impact of environmental heterogeneity and life stage on the hindgut microbiota of Holotrichia parallela larvae (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). PLoS One 8(2), e57169 (2013).

Huang, S., Sheng, P. & Zhang, H. Isolation and identification of cellulolytic bacteria from the gut of Holotrichia parallela larvae (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Int. J. Mol. Sci.13, 2563–2577. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms13032563 (2012).

Theurkar, S. V., Patil, S. B., Ghadage, M. K., Zaware, Y. B. & Madan, S. S. Distribution and Abundance of White grubs (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) in Khed Taluka, part of Northern Western Ghats, MS, India. Int. Res. J. Biol. Sci. 1, 1 (2012).

Zhang, Z. Y. et al. Cultivable anaerobic and aerobic bacterial communities in the fermentation chambers of Holotrichia parallela (coleoptera: scarabaeidae) larvae. Plos One. 13 (1), e0190663 (2018).

Handique, G. et al. Characterization of cellulose degrading bacteria from the larval gut of the white grub beetle lepidiota mansueta (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol.94(2), e21370 (2017).

Huang, S. & Zhang, H. The impact of environmental heterogeneity and life stage on the hindgut microbiota of Holotrichia parallela larvae (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). PLoS One8, 1 (2013).

Kimura, M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol.16, 111–120 (1980).

Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 39, 783–791 (1985).

Lisdiyanti, P., Suyanto, E., Gusmawati, N. F. & Rahayu, W. Isolation and characterization of cellulase produced by cellulolytic bacteria from peat soil of Ogan Komering Ilir, South Sumatera. Int. J. Environ. Bioen3, 145–153 (2012).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem.72, 248–254 (1976).

Miller, G. L. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal. Chem.31, 426–428 (1959).

Zhang, M., Su, R., Qi, W. & He, Z. Enhanced enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulose by optimizing enzyme complexes. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol.160, 1407–1414 (2010).

Haas, B. J. et al. Chimeric 16S rRNA sequence formation and detection in Sanger and 454-pyrosequenced PCR amplicons. Genome Res.21 (3), 494–504 (2011).

Edgar, R. C., Haas, B. J., Clemente, J. C., Quince, C. & Knight, R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics. 27 (16), 2194–2200 (2011).

Keegan, K. P., Glass, E. M. & Meyer, F. MG-RAST, a metagenomics service for analysis of microbial community structure and function. In Microbial environmental genomics (MEG), pp. 207–233 (2016).

Yoon, S. H. et al. Introducing EzBioCloud: a taxonomically united database of 16S rRNA gene sequence database with phylotypes that represent uncultured species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol.62, 716–721 (2017). https://www.ezbiocloud.net. Accessed on 19 June 2024.

Soko, K. M., Bhattacharya, R. C., Ramakrishnan, B., Sharma, K. & Subramanian, S. Functional characterization of bacteria isolated from different gut compartments of white grub, Anamola dimidiata, larvae. J. Environ. Biol.41 (6), 1526–1535 (2020).

Dillon, R. J., Webster, G., Weightman, A. J. & Charnley, A. K. Diversity of gut microbiota increases with aging and starvation in the desert Locust. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 97 (1), 69 (2010).

Briones-Roblero, C. I. et al. Structure and dynamics of the gut bacterial microbiota of the bark beetle, Dendroctonus rhizophagus (Curculionidae: Scolytinae) across their life stages. PloS One. 12 (4), e0175470 (2017).

Yong, H. S., Song, S. L., Chua, K. O. & Lim, P. E. Microbiota associated with Bactrocera carambolae and B. Dorsalis (Insecta: Tephritidae) revealed by next-generation sequencing of 16S rRNA gene. Meta Gene. 11, 189–196 (2017).

Sheng, P., Xu, J., Saccone, G., Li, K. & Zhang, H. Discovery and characterization of endo-xylanase and β-xylosidase from a highly xylanolytic bacterium in the hindgut of Holotrichia parallela larvae. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzymatic105, 33–40 (2014).

Haloi, D. J., Borkotoki, A., Mahanta, R. & Haloi, I. H. Cellulase activity and kinetics in Rice Grasshopper Hieroglyphus banian (Orthoptera: acrididae). Indian J. Sci. Technol.5, 3753–3757 (2012).

Gruno, M., Väljamäe, P., Pettersson, G. & Johansson, G. Inhibition of the Trichoderma reesei cellulases by cellobiose is strongly dependent on the nature of the substrate. Biotechnol. Bioeng.86, 503–511 (2004).

Fischer, R., Ostafe, R. & Twyman, R. M. Cellulases from insects. In Yellow Biotechnol. II 51–64 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013).

Bhattacharyya, B. et al. Evaluation of some granular insecticides against white grub, lepidiota mansueta B. in potato (Solanum tuberosum L). J. Entomol. Zool. Stud.5, 1441–1444 (2017).

Mika, N., Zorn, H. & Rühl, M. Insect-derived enzymes: a treasure for industrial biotechnology and food biotechnology. In Yellow Biotechnol. II 1–17 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013).

Kosewska, O., Przemieniecki, S. W. & Nietupski, M. The effect of antibiotics on Bactriome of Sitophilus orzae and Rhyzopertha dominica as a factor determining the success of foraging: a chance for antibiotic therapy in grain srores. Appl. Sci.13 (3), 1576 (2023).

Gouda, M. R., Subramanian, S., Kumar, A. & Ramakrishnan, B. Microbial ensemble in the hives: deciphering the intricate gut ecosystem of hive and forager bees of Apis mellifera. Mol. Biol. Rep.51 (1), 262 (2024).

Huang, S. W., Zhang, H. Y., Marshall, S. & Jackson, T. A. The scarab gut: a potential bioreactor for bio-fuel production. Insect Sci.17, 175–183 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This research paper forms part of the Ph.D research work of the first author and he gratefully acknowledges the support given by the Graduate School, ICAR-Indian Agricultural Research Institute, New Delhi, and Indian Council for Cultural Relations, Government of India for conducting this research programme. The authors also acknowledge the support given by Flagship Microbiome programme and NAHEP-CAAST programmes of ICAR- IARI, New Delhi. Special thanks should go to members of the Insect Molecular Genetics and Microbial Genetics laboratories of the Division of Entomology and Dr. Bhaskar Reddy for his assistance in analysis.

Funding

NAHEP-CAAST programme and Flagship Project on Microbiome.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KM.: methodology, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, validation, sofware, writing—original draft preparation, reviewing and editing. MNRG.: software analysis and reviewing and editing. BR.: review and editing. AK.: review and editing. SS: methodology, visualization, investigation, resources, conceptualization, review and editing, supervision, project administration, research support.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval statement

This study does not include any animals that require ethical clearance. We confirm that all experiments were performed in accordance with the Institute’s relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Msango, K., Gouda, M.N.R., Ramakrishnan, B. et al. Variation and functional profile of gut bacteria in the scarab beetle, Anomala dimidiata, under a cellulose-enriched microenvironment. Sci Rep 14, 22400 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73417-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73417-5