Abstract

Background: Both lipid metabolism and obesity are crucial factors in osteoporosis, influencing the relevance of the cardiometabolic index (CMI), a new body fat index incorporating obesity and lipid metrics. Our study aims to explore the relationship between CMI and lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD) and the mediating role of body fat percentage. Methods: Utilizing the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 2011 to 2018, we conducted a cross-sectional analysis. We employed multiple linear regression models, subgroup analyses, generalized additive models (GAM), smooth curve fitting, and mediation analysis to evaluate the linear and nonlinear relationships between CMI and lumbar spine BMD. Results: The study involved 5,124 participants with an average lumbar spine BMD of 1.03 ± 0.15 g/cm2. We identified a negative correlation between CMI and lumbar spine BMD (β = -0.015; 95% CI: -0.023, -0.008). Nonlinear associations were evident, with inflection points at CMI values of 1.12 and 2.86. Subgroup analyses showed consistent negative correlations across all categories without significant differences (p for interaction > 0.05). Moreover, body fat percentage negatively correlated with BMD (β = -0.005; 95% CI: -0.006, -0.004) and mediated 9.41% of the relationship between CMI and BMD. Conclusion: Increased CMI levels are associated with lower lumbar spine BMD, with body fat percentage significantly mediating this relationship. This underscores the importance of managing body composition in the context of bone health, highlighting CMI’s potential utility in osteoporosis risk assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiometabolic index (CMI) is a novel body fat index that incorporates both obesity and lipid components, effectively reflecting visceral fat distribution and dysfunction1. It combines anthropometric measures such as the waist-to-height ratio (WHTR) and the triglyceride-to-high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (TG/HDL-C) ratio2. The TG/HDL-C ratio has been shown to accurately depict lipid metabolism in severely obese children, obese adolescents, and obese adults. Previous studies have also confirmed its association with the development of diabetes, abdominal obesity, hyperuricemia, and dyslipidemia3.

Bone mineral density (BMD) serves as the primary method for diagnosing osteoporosis and bone loss4. Osteoporosis (OP) is a common condition of the skeleton that is defined by reduced bone mass and damaged microstructure, which ultimately leads to greater fragility and fracture risk5,6. Utilizing a dual-energy X-ray bone densitometer (DXA) to assess bone density in areas like the lumbar spine, a BMD value of ≤ -2.5 indicates potential osteoporosis6,7. While bone mass stands as a crucial osteoporosis indicator, its detection is more intricate, thus rendering bone density the prevailing choice in clinical settings8. As a metabolic bone ailment, OP ranks high in global prevalence rates following hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and coronary heart disease9,10. Epidemiological studies illustrate osteoporosis prevalence rates of 23.1% in women and 11.7% in men11, with over 50 million U.S. adults affected by osteoporosis and bone loss in 201012. Approximately 30% of women and 20% of men with osteoporosis endure fractures, elevating the United States among nations grappling with high osteoporosis prevalence13. Osteoporosis and its consequential fractures not only precipitate a substantial decline in patients’ quality of life but also inflict severe physical and psychological traumas14. The etiology of bone loss and osteoporosis is multifaceted, encompassing metabolic, genetic, and lifestyle factors15.

Understanding the potential relationship between CMI and BMD is imperative in discerning whether CMI exhibits a positive or negative correlation with osteoporosis. We hypothesize that both positive and negative impacts of CMI on BMD coexist, yet the net effect remains undetermined. Given the deterioration of the metabolic profile in individuals with body fat metabolism disorders over time, accurate monitoring of body fat percentage in osteoporosis patients is crucial for devising effective interventions to avert adverse health outcomes. In this study, we use NHANES data to investigate the relationship between osteoporosis and CMI. Our findings may furnish compelling evidence regarding the involvement of lipid metabolism in the osteoporotic populace, offering invaluable insights for healthcare practitioners in their daily practice.

Materials and methods

Study population

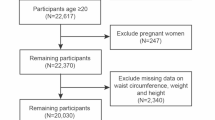

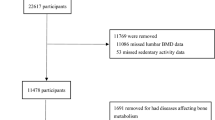

Study participants were recruited from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which utilized a complex, multi-stage, stratified, and clustered probability design to represent the U.S. population. NHANES has been conducted regularly on a 2-year cycle since 1999, aiming to investigate the correlations between nutrition, living environment or habits, and physical health. Each participant in this effort was assigned a unique identification number and participated in one of the survey cycles. Data on demographics, lifestyle, and health status were obtained through questionnaires, physical examinations, and laboratory tests. This study included participants from the NHANES cycles of 2011–2012, 2013–2014, 2015–2016, and 2017–2018 who reported BMD levels. Out of the 39,156 participants initially considered, a total of 5,124 were included after excluding those with missing data: specifically, 11,086 with missing BMD data, 6,407 with missing cardiometabolic index (CMI) data, and 16,539 participants who were under 20 years of age. The National Center for Health Statistics Ethics Review Board approved the study, and informed consent was given by each participant. (Fig. 1)

Study variables

Lumbar spine bone mineral density and body fat percentage measurements were performed using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). The DXA scan not only provides bone and soft tissue measurements for the whole body, arms, legs, trunk, and head but also serves as an internationally recognized screening tool to assess fragility fracture risk. Radiologic technicians, who are certified and trained in DXA screening, conducted the measurements. The whole body scans were acquired using the Hologic Discovery model A densitometers (Hologic, Inc., Bedford, Massachusetts) with software version Apex 3.2. The robustness of these measurements has been affirmed in previous studies16,17,18.

The calculation of the cardiometabolic index (CMI) is based on both anthropometric and biochemical data, including height, waist circumference (WC), triglycerides (TG), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C). Both height and waist circumference are expressed in centimeters (cm), while triglycerides and HDL-C are expressed in milligrams per deciliter (mg/dl)3. The formula for the calculation of CMI is as follows.

Covariates

Age, sex (male or female), race, education, marital status, body mass index (BMI), household income to poverty ratio (household PIR), total cholesterol, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) were the factors chosen for this study. Furthermore, a person’s drinking status is determined by whether or not they have had alcohol at least 12 times in the previous year, and their smoking status is determined by whether or not they have ever smoked 100 cigarettes. Diabetes mellitus was diagnosed by any of the following: informed by a physician or health professional; fasting blood glucose ≥ 126 mg/dl; HBA1c level ≥ 6.5%; or use of antidiabetic medications including insulin. Hypertension was diagnosed by any of the following: informed by a physician or health professional; use of antihypertensive medications; or mean systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg and/or mean diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg. To enhance the transparency of our methodology, we referenced previous studies for detailed information on these variables1. All study variables’ composite measures are accessible on the NHANES website. (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/).

Statistical analysis

For this study, we applied complex sampling weights to all analyses to better represent the entire population of the United States, by the NCHS analytic guidelines. To investigate the correlation between the cardiometabolic index (CMI) and lumbar bone mineral density (BMD), we utilized weighted linear regression or chi-square tests to assess differences between CMI quartiles. Weighted survey means ± standard deviation (SD) are used to express continuous data, whereas weighted survey percentages are used to express categorical variables.

To explore the association between the cardiometabolic index (CMI) and lumbar bone mineral density (BMD), we utilized three linear regression models: unadjusted, minimally adjusted, and fully adjusted for covariates. Model 1 was unadjusted; Model 2 was adjusted for age, race, and sex; and Model 3 included adjustments for sex, race, age, BMI, PIR, education, marital status, smoking, alcohol consumption, diabetes, and hypertension. We conducted weighted linear regression analyses using CMI as both a continuous variable and a categorical variable (quartiles), estimating trends by treating CMI quartiles as continuous variables. Additionally, we examined the nonlinear association between CMI and kidney stone prevalence using a generalized additive model (GAM) and smooth curve fitting. When nonlinear associations were identified, a two-segment linear regression model (segmented regression model) was fitted to each interval and compared with a single-linear model (non-segmented model) using a log-likelihood ratio test. Threshold effects and corresponding inflection points were calculated. Subsequently, subgroup analyses and interaction tests were conducted to evaluate the potential confounders listed in the baseline table.

Finally, we utilized weighted multiple linear regression analysis to assess the association between body fat percentage and lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD). Furthermore, mediation analyses were performed to examine the potential mediating effect of body fat percentage on the association between the cardiometabolic index (CMI) and lumbar BMD. The formula (mediated effect/total effect) × 100% was used to calculate the proportion of effect mediated by body fat percentage. R (http://www.r-project.org) and EmpowerStats (http://www.empowerstats.com) were used for the statistical analysis of this study, with a significance threshold of P < 0.05.

Results

Basic characteristics of the study population

As shown in Table 1, a total of 5124 individuals aged between 20 and 59 years were included in our study. The mean age of the participants was 39.67 ± 11.72 years, with 53.11% being male. The mean bone mineral density of the lumbar spine was 1.03 ± 0.15 g/cm2. The bone mineral densities for the quartile groups according to the CMI level were as follows: 1.05 ± 0.14 g/cm2, 1.04 ± 0.15 g/cm2, 1.03 ± 0.15 g/cm2, and 1.02 ± 0.14 g/cm2, respectively, with significant differences between the groups. The body fat percentages according to CMI level quartiles were 29.81 ± 8.14%, 29.81 ± 8.14%, 33.99 ± 8.33%, and 33.95 ± 7.35%, respectively, also showing significant differences between groups (p < 0.05). Compared to the other quartiles, the highest CMI quartile population was predominantly male, white, and moderately educated, with a high percentage of married individuals, and those with a BMI greater than 30.

Association between CMI and lumbar bone mineral density

Table 2 presents the multivariate linear regression analysis between the cardiometabolic index (CMI) level and lumbar spine bone mineral density, indicating a negative correlation between the two. Specifically, in Model 3, for each unit increase in CMI, lumbar spine bone mineral density decreased by 0.015 g/cm2 (β = -0.015, 95% CI: -0.023, -0.008). The CMI was transformed from a continuous variable to a quartile one. Compared with the lowest quartile, participants in the highest quartile of CMI experienced a decrease in bone mineral density of 0.037 g/cm2 (β = -0.037, 95% CI: -0.050, -0.024). As CMI was categorized into quartiles, the reduction in bone mineral density became significantly more pronounced with increasing CMI quartiles (p for trend < 0.001) (Table 2).

Smooth curve fitting and threshold effect analysis

We further explored the nonlinear relationship between cardiometabolic index (CMI) levels and lumbar vertebral bone mineral density using generalized additive modeling and smoothed curve fitting (Fig. 2). Additionally, our results indicated a nonlinear relationship between CMI levels and kidney stones. Using a recursive algorithm, we determined the inflection points at 1.12 and 2.86 for the saturation threshold effect analysis (log-likelihood ratio test p-value < 0.05) (Table 3). On the left side of the inflection point 1.12, each unit increase in CMI decreased lumbar bone mineral density by 0.032 g/cm2 (β = -0.032, 95% CI: -0.047, -0.017), with a p-value of < 0.001. On the right side of inflection point 1.12, there was no statistically significant association between CMI and lumbar bone mineral density (p-value = 0.926). Similarly, on the right side of inflection point 2.86, each unit increase in CMI was associated with a 0.054 g/cm2 decrease in lumbar spine bone mineral density (β = -0.054, 95% CI: -0.102, -0.006), with a p-value of 0.028. On the left side of inflection point 2.86, no statistically significant association was observed between CMI and bone mineral density (p-value = 0.083).

Subgroup analysis

As shown in Fig. 3, there was a negative correlation between the cardiometabolic index (CMI) and lumbar spine bone mineral density in all subgroups, with no significant variation observed across these subgroups (p for interaction > 0.05). In the gender subgroups, there was a decreasing trend in bone mineral density levels for both men [-0.017 (-0.026, -0.008), p = 0.001] and women [-0.012 (-0.024, -0.001), p < 0.074]. Similarly, a decreasing trend was noted in bone mineral density levels in both the 20–40 age group [-0.020 (-0.031, -0.009), P = 0.001] and the 40–59 age group [-0.013 (-0.022, -0.003), P = 0.007].

Subgroup analysis between CMI and lumbar spine bone mineral density(g/cm2). Note 1: The above model was adjusted for age, gender, race, education level, marital status, the ratio of income to poverty (PIR), body mass index (BMI), smoking status, diabetes status, alcohol drinking status, and hypertension. Note 2: In each case, the model does not adjust for the stratification variable. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. PIR represents the ratio of income to poverty. CMI stands for cardiometabolic index, and BMI for body mass index.

Association between body fat percentage and mineral density of lumbar vertebrae

We further explored the multiple linear regression analysis between body fat percentage and lumbar bone mineral density, which showed a negative correlation with lumbar bone mineral density across all three models. In model three, each unit increase in body fat percentage was associated with a 0.005 g/cm2 decrease in lumbar spine bone mineral density (β = -0.005, 95% CI: -0.006, -0.004). We converted body fat percentage from a continuous variable to a quartile variable. Participants in the highest quartile of body fat percentage experienced a 0.091 g/cm2 decrease in bone mineral density compared to those in the lowest quartile (β = -0.091, 95% CI: -0.112, -0.071). As body fat percentage was grouped into quartiles, the reduction in bone mineral density became more significant with increasing quartiles (p for trend < 0.001) (Table 4).

Intermediary analysis

Mediation analysis was further employed to explore the mediating role of body fat percentage between the cardiometabolic index (CMI) and lumbar spine bone mineral density. The results indicated that body fat percentage had a significant indirect effect, with a mediation ratio of 9.41% (Table 5).

Discussion

A nationally representative sample was used in this study to investigate the relationship between osteoporosis, lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD), and the cardiometabolic index (CMI). The findings suggest that elevated CMI levels may be associated with reduced lumbar spine BMD among U.S. adults. This association’s robustness was further validated by adjusting for multiple potential confounders. Moreover, the study revealed an S-shaped nonlinear relationship between CMI and lumbar spine BMD, with inflection points occurring at 1.12 and 2.86, respectively (p-value < 0.05 for the log-likelihood ratio test). To the left of the inflection point at 1.12, lumbar BMD decreased by 0.032 g/cm2 for each unit increase in CMI, while to the right of the inflection point at 2.86, lumbar BMD decreased by 0.054 g/cm2 per unit increase in CMI. Additionally, the study showed that body fat percentage played an important role in modulating the relationship between lumbar spine BMD and CMI, explaining 9.41% of CMI’s effect on lumbar spine BMD. These findings not only indicate the importance of body fat percentage in osteoporosis risk assessment but also emphasize the complex role of lipid metabolism in BMD changes.

Overweight is a risk factor in and of itself for disorders related to the cardiometabolic circuit. Individuals harboring surplus body fat exhibit heightened incidences of insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome, amplifying the risk of premature mortality19. Heightened cytokine secretion in individuals with elevated body fat percentages obstructs insulin receptor signaling, instigating insulin resistance and precipitating alterations in lipid distribution, culminating in the onset of cardiometabolic diseases20. Moreover, as fat accumulates within arteries, the heart contends with heightened strain to circulate blood throughout the body, augmenting pressure on arterial walls21. Concurrently, cardiac metabolic irregularities can foster abdominal obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, and hypertension22. Sex hormones have emerged as pivotal factors in governing body fat storage, distribution, and catabolism, contributing to gender disparities in body fat quantity and distribution23,24. Estrogen directly influences the expression of obesity genes, whereas androgens stimulate energy expenditure and act as lipolysis promoters. Additionally, androgens regulate muscle growth and development, promoting ongoing muscle hypertrophy to a certain extent25. Collectively, a correlation exists between body fat percentage and cardiac metabolism. In our study, we scrutinized the relationship between CMI and body fat percentage within the study cohort, revealing a trend of escalating body fat percentage with increasing CMI quartiles (p-value < 0.0001). This underscores and reinforces the association between CMI and body fat percentage.

Numerous studies have confirmed a remarkable relationship between the proportion of fat stored and the amount of bone mineral., in addition to a strong inverse relationship between the body’s fat proportion and osteoporosis26,27. Notably, in a study involving individuals with type 2 diabetes, low body fat percentage emerged as the most accurate predictor of bone mineral loss28. A proportion of an individual’s body weight comprises muscle and bone29. Increased muscle mass necessitates heightened physical activity to sustain, imposing additional mechanical stresses on the skeleton, thereby elucidating the stronger impact of low body fat percentage on bone health. Certain animal experiments have evidenced that when osteoblasts receive shear stress signals, the secretion of sclerostin diminishes, curbing apoptosis, while osteoclast activity is suppressed, fostering osteoblast differentiation and consequent bone density augmentation16. In our study, subgroup analysis comparing genders unveiled a declining trend in BMD levels among both men and women. However, with a P-value for the interaction of 0.268, With the fact that there is a relationship between bone density and the percentage of fat in the body that is more pronounced in males compared to females, the discrepancy is not statistically significant. This could be attributed to the significantly greater muscle mass and strength in males, necessitating coordinated muscle-bone interactions during daily physical activity, which can transfer mechanical loads to bones and induce osteogenic responses30. The percentage of body fat tends to be higher in women than in men, leading to increased mechanical loads on the skeleton due to higher body weight and promoting osteoblast differentiation31. Consequently, the lumbar spine, bearing the heaviest loads at higher bone densities, exhibits the most pronounced effect of adiposity on bone density10. Furthermore, our analysis of the relationship between lumbar vertebral bone density and fat mass quartiles revealed a gradual decline in bone density with increasing body fat percentage quartiles from Q1 (lowest) to Q4 (highest), with a significant trend observed (p-value < 0.001). These findings suggest a negative correlation between body fat percentage and lumbar spine bone density, implying that an elevation in body fat percentage may precipitate a decrease in lumbar spine bone density, a correlation that persists even after adjusting for multiple covariates.

After converting CMI from a continuous to a quartile variable, we carried out a thorough investigation to examine the connection between CMI and the lumbar spine density of bones. Notably, participants in the highest CMI quartile exhibited markedly lower lumbar spine BMD, with a reduction of 0.037 g/cm2. This reduction was statistically significant when compared to the lowest CMI quartile group. Moreover, the trend of decreasing BMD among participants as CMI quartiles ascended was highly significant. We adjusted for this association in three distinct models, even after controlling for confounding variables, there was still a statistically significant connection between CMI and lumbar spine density of bones.

Furthermore, we conducted a mediated effects analysis, which revealed a Total effect of -0.0085, signifying a negative influence of CMI on lumbar spine bone density. The Direct effect was determined to be -0.0077, indicating that CMI retained a negative association with lumbar spine bone density even after factoring in the effect of body fat percentage. The mediator ratio was calculated at 9.41%, indicating a partial explanation of the link between CMI and lumbar spine bone density may be provided by the mediator effect. However, it is necessary to compare this effect with other potential mediators, such as inflammatory markers, insulin resistance, and lipid profiles. Inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-6, are known to promote bone resorption through the activation of osteoclasts and therefore may mediate the relationship between CMI and BMD32. Similarly, insulin resistance is associated with impaired bone formation and increased bone resorption, which further affects this relationship33.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several significant strengths and unique features. First, the use of the NHANES database enabled the production of nationally representative estimates, supported by its rigorous quality assurance protocols that ensure data accuracy and reliability. Second, the breadth of the NHANES dataset ensured that its sample was representative, thereby increasing the applicability of the study’s results. Third, this study employed generalized additive models (GAM) and smoothed curve fitting methods to reveal a nonlinear relationship between CMI and BMD, which contrasts with the linear relationships typically found in most studies. This finding suggests that changes within specific CMI ranges may have a more significant impact on BMD. Fourth, the mediating role of body fat percentage between CMI and BMD is another important finding of this study. While previous research primarily investigated the direct relationship between body fat and BMD, the present study demonstrated that body fat percentage not only directly affects BMD but also indirectly influences BMD by modulating CMI.

However, this study also has some limitations. First, due to its cross-sectional design, although this study revealed an association between CMI and lumbar spine BMD, it was unable to determine a causal relationship. The relationship between CMI and BMD may be influenced by various factors, and this study could not clarify the causal order of these factors using cross-sectional data. Second, although we observed a greater difference in BMD between the first and fourth quartiles of CMI, the difference between the second and third quartiles was less significant. This phenomenon may indicate a smaller or stabilizing biological effect of BMD changes at intermediate CMI levels. Third, changes in BMD are an ongoing physiological process, and cross-sectional data only reflect conditions at a single point in time, failing to capture the dynamic changes in bone health. Future studies should adopt a longitudinal design to measure changes in CMI, body fat percentage, and BMD in individuals through multiple follow-up visits, thereby providing a better understanding of the causal relationships and dynamic processes among these variables.

Conclusion

In summary, the results of this study showed that increased CMI levels were associated with lower lumbar bone mineral density and that body fat percentage played an important mediating role between CMI and lumbar bone mineral density. It is suggested that proper obesity control may be an effective adjunct to increase bone mineral density.

Data availability

The survey data are publicly available on the internet for data users and researchers throughout the world ( www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/ ).

Abbreviations

- CMI:

-

Cardiometabolic index

- BMD:

-

Bone mineral density

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- GAM:

-

Generalized additive model

- PIR:

-

Income to poverty ratio

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

- TG:

-

Triglycerides

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- WHTR:

-

Waist-to-height ratio

- DXA:

-

Dual-energy X-ray bone densitometer

References

Xue, H. et al. The association between different physical activity (PA) patterns and cardiometabolic index (CMI) in US adult population from NHANES (2007–2016). Heliyon. 10 (7), e28792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28792 (2024).

Wakabayashi, I. (ed Daimon, T.) The cardiometabolic index as a new marker determined by adiposity and blood lipids for discrimination of diabetes mellitus. Clin. Chim. Acta 438 274–278 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2014.08.042 (2015).

Cheng, L., Wu, Q. & Wang, S. Cardiometabolic index is associated with increased depression: A population-based study. J. Affect. Disord. 348, 259–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.12.073 (2024).

Sun, A., Hu, J., Wang, S., Yin, F. & Liu, Z. Association of the visceral adiposity index with femur bone mineral density and osteoporosis among the U.S. older adults from NHANES 2005–2020: A cross-sectional study. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1231527. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1231527 (2023).

Kanis, J. A. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: Synopsis of a WHO report. WHO Study Group. Osteoporosis Int. 4(6), 368–381 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01622200

Lane, N. E. Epidemiology, etiology, and diagnosis of osteoporosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 194 (2 Suppl). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2005.08.047 (2006).

Black, D. M. & Rosen, C. J. Clinical practice. Postmenopausal osteoporosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 374 (3), 254–262. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1513724 (2016).

Yang, Y., Wang, S. & Cong, H. Association between parity and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. BMC Women’s Health. 22 (1), 87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01662-9 (2022).

Wang, X., Yang, S., He, G. & Xie, L. The association between weight-adjusted-waist index and total bone mineral density in adolescents: NHANES 2011–2018. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1191501. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1191501 (2023).

Hassan, A. B. et al. The estimated prevalence of osteoporosis in Bahrain: A multi-centered-based study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 25 (1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-023-07145-8 (2024).

Sun, X. & Wu, X. Association of apolipoprotein A1 with osteoporosis: A cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 24 (1), 157. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-023-06264-6 (2023).

Luo, Y. et al. Correction: Association between dietary selenium intake and the prevalence of osteoporosis and its role in the treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 19 (1), 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-023-04500-2 (2024).

Tian, N., Chen, S., Han, H., Jin, J. & Li, Z. Association between triglyceride glucose index and total bone mineral density: A cross-sectional study from NHANES 2011–2018. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 4208. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54192-9 (2024).

Dutta, S. M. et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis of the Hippocampus of rats with GCR-Induced spatial memory impairment. Radiat. Res. 189 (2), 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1667/rr14822.1 (2018).

Yi, S. J., Lim, J. & Kim, K. Exploring epigenetic strategies for the treatment of osteoporosis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 51 (1), 398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-024-09353-4 (2024).

Bai, T. et al. The association between brominated flame retardants exposure with bone mineral density in US adults: A cross-sectional study of the national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 2005–2014. Environ. Res. 251 (Pt 1), 118580. (2024).

Lee, C. L., Tzeng, H. E., Liu, W. J. & Tsai, C. H. A cross-sectional analysis of the association between sleep duration and osteoporosis risk in adults using 2005–2010 NHANES. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 9090. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-88739-x (2021).

Xie, R., Huang, X., Liu, Q. & Liu, M. Positive association between high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and bone mineral density in U.S. adults: The NHANES 2011–2018. J. Orthop. Surg, Res. 17 (1), 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-022-02986-w (2022).

Wong, J. C., O’Neill, S., Beck, B. R., Forwood, M. R. & Khoo, S. K. Comparison of obesity and metabolic syndrome prevalence using fat mass index, body mass index and percentage body fat. PloS One. 16 (1), e0245436. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245436 (2021).

Lazzer, S. et al. Cardiometabolic Index (CMI) and visceral Adiposity Index (VAI) highlight a higher risk of metabolic syndrome in women with severe obesity. J. Clin. Med. 12 (9). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093055 (2023).

Li, H., Zhang, Y., Luo, H. & Lin, R. The lipid accumulation product is a powerful tool to diagnose metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease in the United States adults. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 977625. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.977625 (2022).

Noonan, R. J. The influence of adolescent Sport participation on body mass index tracking and the association between body mass index and self-esteem over a three-year period. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19 (23). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315579 (2022).

Fan, H. et al. Recent advances in senescence-associated secretory phenotype and osteoporosis. Heliyon. 10 (4), e25538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e25538 (2024).

Yin, B. et al. Non-linear association of atherogenic index of plasma with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22 (1), 157. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-01886-5 (2023).

Xu, J. et al. Proteome-wide profiling reveals dysregulated molecular features and accelerated aging in osteoporosis: A 9.8-year prospective study. Aging cell. 23 (2), e14035. https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.14035 (2024).

Bernardes, M. et al. Coronary artery calcium score in female rheumatoid arthritis patients: Associations with apolipoproteins and disease biomarkers. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 22 (10), 1841–1856. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185x.13685 (2019).

Blaschke, M. et al. Crohn’s disease patient serum changes protein expression in a human mesenchymal stem cell model in a linear relationship to patients’ disease stage and to bone mineral density. J. Clin. Transl. Endocrinol. 13, 26–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcte.2018.06.002 (2018).

Huang, Y. H. et al. POU2F3 is a master regulator of a tuft cell-like variant of small cell lung cancer. Genes Dev. 32 (13–14), 915–928. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.314815.118 (2018).

Shi, D., Liu, W., Hang, J. & Chen, W. Whole egg consumption in relation to bone health of the US population: A cross-sectional study. Food Funct. 15 (3), 1369–1378. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3fo04248k (2024).

Yuan, C. & Li, J. Research progress of periostin and osteoporosis. Front. Endocrinol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2024.1356297 (2024).

Zhao, Y. et al. Revealing oxidative stress-related genes in osteoporosis and advanced structural biological study for novel natural material discovery regarding MAPKAPK2. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 1052721. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.1052721 (2022).

Redlich, K. & Smolen, J. S. Inflammatory bone loss: Pathogenesis and therapeutic intervention. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.. 11 (3), 234–250. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd3669 (2012).

Leslie, W. D. & Morin, S. N. Osteoporosis epidemiology 2013: implications for diagnosis, risk assessment, and treatment. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 26 (4), 440–446. https://doi.org/10.1097/bor.0000000000000064 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HL, HD and YZ designed the research. MJ, HH and YY collected, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. HJ revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

The portions of this study involving human participants, human materials, or human data were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the NCHS Ethics Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, H., Dong, H., Zhou, Y. et al. Nonlinear relationship between cardiometabolic index and bone mineral density in U.S. adults: the mediating role of percent body fat. Sci Rep 14, 22449 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73427-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73427-3