Abstract

Replacing cement with lithium slag and fine aggregate with rubber in concrete solves waste disposal, reduces material consumption, boosts sustainability, and enhances concrete performance. A set of prismatic concrete specimens with varying proportions were designed and experimentally tested in order to study the compressive stress-strain behavior of lithium slag rubber concrete (LSRC). The main factors affecting the specimens were lithium slag substitution ratio (SL=0%, 10%, 20%, 30%) and rubber substitution ratio (SR=0%, 5%, 10%, 15%). The results demonstrated that the LSRC exhibited good integrity during the damage. Furthermore, the incorporation of lithium slag (LS) was found to effectively compensate for the reduction in compressive strength due to the incorporation of rubber. When 10% of the fine aggregate was replaced with rubber and 20% of the cement was substituted with lithium slag, the axial compressive strength, elastic modulus, and peak strain of the tested specimens increased by 21.57%, 6.92%, and 17.26%, respectively. Compared with ordinary concrete, LSRC has good toughness, impact resistance and durability with minimal loss of strength, and has broad application prospects in engineering fields (such as airports, highways, housing expansion joints, concrete floors and railway concrete sleepers, etc.). Based on the experimental data, simplified modified equations to predict the compressive strength, elastic modulus, peak strain and axial stress-strain constitutive model of LSRC were proposed, so as to promote the development of LSRC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the continuous development of industry, the disposal of polymeric material waste (such as rubber, polyethylene terephthalate, nylon, etc.) and industrial waste residues (such as fly ash, coal gangue, lithium slag, etc.) has become increasingly prominent, which poses a serious challenge to sustainable development and solid waste management. In this context, it is particularly urgent and important to explore and implement effective recycling strategies1. The application of these wastes in concrete manufacturing not only significantly reduces waste accumulation and saves natural resources, but also effectively reduces the consumption of traditional raw materials such as cement and aggregate2. At present, there are more and more researches on the application of polymer material waste and industrial waste residue in concrete3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Many studies have shown that reasonable incorporation into concrete can not only bring significant environmental benefits, but also effectively improve the performance of concrete, achieving a win-win situation of environmental protection and performance improvement.

At present, about 1 billion tires are discarded globally every year, more than half of which are improperly disposed of, posing a serious challenge to the environment and resources12. After the waste rubber is converted into particles or powder and added to concrete, it can not only effectively reduce the emission of CO2, but also significantly improve the green index of the environment13,14, and also perform well in impact resistance, cracking resistance and other properties15,16. Gupta et al.17,18,19 revealed through a series of studies that the incorporation of rubber fiber and rubber powder into concrete significantly improved its impact resistance, fatigue durability and flexural bearing capacity. It was also found that the hydrophobicity of rubber fiber improved the acid and alkali resistance and chloride resistance of concrete, making it suitable for application in chemical floors and sewage pipes20. Nejad et al.21 incorporated different amounts of rubber into concrete to replace sand and cement, respectively, and used five physical methods to reinforce the rubber. It indicated that rubber powder can improve concrete performance more effectively when replacing sand than when replacing cement, and this is verified by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis. Feng et al.22 noted that concrete with a rubber content of 30% showed the highest sensitivity and superior energy absorption capacity in dynamic splitting tensile tests. However, when the rubber content was too high, the toughness of concrete was not enhanced. This suggested that the toughness of concrete did not continue to rise with increasing rubber content. However, the rubber itself is low in strength, and incorporation increases the porosity of the material, which weakens the structural integrity and strength. Gerges et al.23 found that the partial substitution of rubber powder for fine aggregates in concrete improved the impact resistance, density, and toughness of the concrete, but the inherent hydrophobicity and high deformation properties of the rubber material hindered strong adhesion to the cement paste. This deficiency significantly affects the compressive strength, making rubber concrete (RC) have to sacrifice its own strength while exhibiting good toughness and durability, which has become a key factor limiting its further development.

Meanwhile, in China, with the rapid development of new energy fields, the market demand for lithium batteries is becoming more and more vigorous24. Lithium slag (LS), as a byproduct of lithium salt production, not only occupies valuable space but also contributes to environmental pollution25,26. Nevertheless, research has illuminated its immense potential in construction materials. Incorporating an optimal quantity of LS into concrete has been found to bolster its compressive strength, offering a viable solution to mitigate environmental concerns27. This view was also confirmed at the micro level. Qin et al.28 explored the micro-structure of lithium slag recycled concrete using SEM and found that the incorporation of LS optimized the spatial skeleton structure between the hydration products of the concrete and the aggregates, resulting in a tighter connection and better continuity between the aggregates. Dong et al.29 investigated the effect of replacing magnesium ammonium phosphate cement by different proportions of LS on the properties of the mortar. They found that when LS admixture was increased from 0 to 10%, the mechanical properties of mortar were improved. Further X-Ray diffraction and SEM evaluations verified enhanced hydration products and refined micro-structure in mortar containing 10% LS. In addition, Li et al.30 conducted an in-depth analysis of the microstructure of Li-doped composite active powder concrete through SEM and thermogravimetric tests, and found that LS has certain pozzolanic activity, which can play a chemical filling role in the interior of concrete and effectively improve its microstructure. This pozzolastic activity of LS enables it to enhance concrete durability in acidic environments by improving pore structure, reducing permeability, reducing the amount of calcium hydroxide, and increasing the amount of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel31. Zhao et al.32 used LS as a mineral admixture instead of cement, and the results showed that LS could densify the microstructure of the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) of concrete, reduce the internal porosity, and improve the erosivity of chloride ions and sulfate. Zhang et al.33 also found that LS had a positive effect on hydration, improving the compactness of concrete and reducing the Ca/Si of C-S-H gel in concrete, indicating its acid rain corrosion resistance. This shows that proper incorporation of LS into concrete can significantly improve the strength and durability of concrete, and enhance the compressive and flexural properties and corrosion resistance of acid rain and chloride ions by optimizing the microstructure.

In the past, most studies focused on the performance change of a single waste after incorporation into building materials, and few studies used waste rubber and lithium slag as raw material substitutes for concrete at the same time to analyze the combined impact on concrete performance. The inclusion of waste rubber improves the impact resistance, cracking resistance and dynamic splitting tensile properties of concrete, but its low strength and increased porosity also lead to strength loss. On the contrary, lithium slag can effectively enhance the compressive strength of concrete and optimize the internal structure through its pozzolanic activity and microscopic filling. The combination of the two not only retains the original excellent toughness of rubber concrete, but also makes up for its deficiency in strength through the enhancement of lithium slag. In addition, these two materials have shown advantages in improving the durability of concrete, especially in harsh environments such as acid, which brings extremely optimistic prospects for improved performance, longer life and lower maintenance costs of structural infrastructure31. This not only solves the problem of lithium slag and waste rubber disposal, greatly improves the efficiency of sustainable development, but also reduces the saving of resources, reduces the cost, and improves the performance of concrete. To explore the performance characteristics of this innovative green building material, this paper delves into the axial compressive mechanical properties of lithium slag rubber concrete (LSRC). According to previous research, excessive incorporation of LS or rubber could weaken the mechanical properties of concrete, while moderate incorporation could bring improved performance. Specifically, the optimum value of the lithium slag substitution ratio (SL) should be controlled in the range of 0–30%34, while the optimum value of the rubber substitution ratio (SR) should be in the range of 0–15%35,36. Therefore, the above optimal substitution ratio intervals were used as a reference basis in the experimental design. The effects of different SL and SR on the compressive strength, elastic modulus, peak strain and stress-strain relationship of concrete were analyzed through the tests.

Experimental program

Raw materials

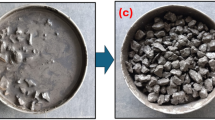

Masonry cement with a grade of 32.5 was used in this work. The LS used is shown in Fig. 1(a). The coarse aggregate consisted of natural crushed stone ranging in size of 5–20 mm. The fine aggregate mixture comprised two distinct components. The first component comprised naturally occurring, meticulously graded river sand, featuring a fineness modulus of 2.6. The second component, depicted in Fig. 1(b), consisted of rubber granules derived from the pulverization of discarded tires, exhibiting a particle size range of 0.5–2 mm. Figure 2 illustrates the particle size classification of coarse aggregate and sand. In addition, the cumulative distribution curves of the particle size of cement and LS were plotted and analyzed in conjunction with the scanning electron microscope diagrams, as shown in Fig. 3, and found to be very close to each other. Table 1 presents the chemical compositions of both cement and LS. Ordinary city tap water was used in the mixing process.

Mix proportions and specimen preparation

To investigate the influence of LS and rubber substitution ratios on the axial compressive properties of concrete, a methodical approach involving trial-and-error was employed. Specifically, LS was substituted with equal mass of cement (0%, 10%, 20% and 30%) and rubber was substituted with equal mass of fine aggregate (0%, 5%, 10% and 15%). Table 2 shows the proportions of the various concrete mixes, where ‘L’ stands for lithium slag, ‘R’ stands for rubber and the numbers indicate the corresponding substitution ratios. For example, L10R5 means SL=10% and SR=5% in this specimen. The concrete mix ratio was determined in accordance with the “Ordinary Concrete Mix Design Regulations”37.

In this experiment, prismatic test specimens measuring 100 mm by 100 mm in cross-section and 300 mm in length were prepared following the Chinese standard38, with three test blocks in each group. Among them, the reference specimen (L0R0) was prepared without adding LS and rubber. During the experiment, the component materials were meticulously weighed as per the proportions outlined in Table 2 and initially dry-mixed in a laboratory mixer. After a minute elapsed, water was incrementally introduced to guarantee a homogeneous blend of the mixture, which was then mixed for an additional minute. Promptly following this, the well-mixed concoction was swiftly poured into identically sized molds. In order to ensure the compactness of the specimen and to reduce the internal voids, the molds underwent vibration processing on a dedicated shaking table. After vibration compaction, the concrete specimens were allowed to stand at a constant temperature for 24 h, followed by demoulding. The specimens were then immersed in a water reservoir for a standard 28-day curing period to ensure complete curing of the concrete matrix. Upon completion of curing, the specimens were removed for natural drying and prepared for subsequent mechanical property tests and analyses.

Testing equipment and methods

As shown in Fig. 4, equipment precisely controlled by a microcomputer is used, with a maximum load capacity of up to 3000 kN. During the experiment, the displacement collector installed on the lower side of the lower plate was used to automatically collect the vertical deformation data of the specimen and transmit them to the computer in real time via electrical signals. To facilitate control of the loading process, a displacement-guided loading was employed, which maintained a constant loading velocity of 0.3 mm/min. The test was terminated when the strength of the specimen decreased by about 50% to ensure that sufficient data were collected to fully construct the entire stress-strain curve, including its rising and falling segments.

Experimental program

The axial compressive properties of LSRC prisms with different SL and SR are shown in Table 3. Compressive strength (fc) was the peak stress to which a specimen is subjected under axial pressure, and peak strain (εc) is the strain here. Elastic modulus (Ec) of concrete was defined as the proportionality between compressive strain and stress under axial compression conditions, and here the positive secant modulus in the ascending section of the stress-strain curve from the initial point to 0.4fc was used as the value of Ec. Δ1, Δ2 and Δ3 represented the variation ratios of different test blocks relative to the axial compressive strength (fc0), elastic modulus (Ec0), and peak strain (εc0) of normal concrete, respectively.

In order to better investigate the impact of substitution ratio on concrete, all specimens were categorized into three groups. Group 1 (L0R0, L10R0, L0R10, L10R10) compared the differences between normal concrete, single-mixed LSRC, and compound-mixed LSRC with respect to the relationship between SL and SR. Group 2 (L10R0, L10R5, L10R10, L10R15) demonstrated the variation rule of axial compressive properties of concrete with the change of SR when SL is 10%, and Group 3 (L0R10, L10R10, L20R10, L30R10) responded the change pattern of axial compressive properties with the variation of SL when SR is 10%.

Experimental phenomenon

Figure 5 demonstrates the damage patterns of some concrete samples. The experimental findings revealed that, the deterioration process undergone by these samples was fundamentally analogous to that seen in standard concrete (L0R0), when LS and rubber were employed as substitutes for fractions of the cementitious binder and fine filler material, respectively. Small cracks appeared at the edge of the specimen at the beginning. With the increase of load, the cracks gradually deepened and expanded, and the sound of aggregate being squeezed gradually increased. After failure, most of the specimens broke along the diagonal and spalled at the corners, as shown in Fig. 5(a).

Adding LS slightly affected concrete’s axial compression failure mode but hindered crack propagation. Specimen L10R0 showed fewer main crack forks and less fracture at crack openings (Fig. 5b). This was due to LS enhancing the spatial structure between cement paste and aggregates, making connections denser and more continuous28.

The addition of rubber alone (L0R10) improved the impact resistance of concrete39,40,41, weakened the driving force of crack propagation and delayed the localization of cracks on the macro level42, reduced the brittleness of concrete and enhanced the deformation adaptability43, resulting in obvious interruption of main cracks, fine cracks became fine and numerous, and no obvious spalling phenomenon occurred. High integrity is maintained, as shown in Fig. 5(c).

When both were mixed into the concrete at the same time, the specimen L10R10 was also relatively intact when destroyed, and the destruction pattern was very close to that of ordinary concrete. However, because the LS made the connection between the aggregate cement slurry more dense and rubber buffered the micro-cracks, the surface cracks of the specimen were finer, as depicted in Fig. 5(d).

Axial compressive strength

The variations in axial compressive strength for LSRC prisms, featuring distinct proportions of SL and SR are presented in Table 3; Fig. 6. From Group 1, it reveals that moderate incorporation of LS alone increases the compressive strength of concrete, whereas the sole addition of rubber leads to a reduction in this property. In contrast to the L0R0 reference, the inclusion of 10% LS alone resulted in a 13.31% increase in compressive strength, reaching a value of 24.51 MPa. Conversely, the addition of 10% rubber alone resulted in a 23.90% decrease in compressive strength to 16.46 MPa.

From Group 2, it is observable that the compressive strength diminishes with the increase of SR. When SL was 10%, the strengths of specimens with SR of 5%, 10% and 15% decreased by 16.52%, 24.15% and 44.47%, respectively. This phenomenon is predominantly attributed to the inherent hydrophobicity of rubber particles, leading to the formation of a considerably weakened interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between the aggregate and the cementitious matrix17,44. And due to the low elastic modulus, the deformation of rubber and aggregates was inconsistent, resulting in stress concentration30,45, which accelerated the destruction of ITZ. In addition, due to their low specific gravity, the rubber particles exhibited poor adhesion to cementitious materials and were prone to rise to the concrete surface during vibrating processes. This resulted in uneven distribution within the matrix, ultimately contributing to a reduction in the overall strength of the concrete46,47. At the same time, the addition of rubber not only changed the composition of concrete, but also negatively affected its chemical reactions and hydration process. Specifically, RC contained much higher levels of carbon and sulphur impurities than normal concrete, and these impurities triggered unfavourable chemical reactions during the hydration process48. Further, the inclusion of zinc interfered with the normal hydration process. Zinc’s tendency to interact with Ca2+ and OH− ions, fostering the precipitation of insoluble zincate compounds such as zinc silicate hydrate or calcium zinc silicate hydrate, impeded the timely formation of vital cementitious products like calcium hydroxide (CH) and calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H). Consequently, this hindered development diminished the structural integrity and overall strength of the concrete49.

From Group 3, it is observable that the compressive strength of concrete grows and later diminishes with the increase of SL. When SR was 10%, the strength of the specimens with SL of 10% and 20% increased by 12.94% and 21.57%, respectively. LS was rich in reactive SiO2, Al2O3, and a high proportion of amorphous mineral phases, which allowed it to exhibit good volcanic ash activity without calcination or mechanical activation50,51,52. These active ingredients were found to be capable of reacting with CH, which is generated throughout the hydration process of cement, ultimately leading to the creation of an array of compounds exhibiting enhanced strength properties. Among these are C-S-H, calcium aluminate hydrate (C-A-H), AFt, and AFm50,53,54. The freshly synthesized compounds were capable of densely occupying the voids within the concrete matrix, substantially enhancing the compactness and robustness of the concrete structure via their filling capabilities and volcanic ash-like effects55. In addition, the presence of LS also led to a volcanic ash reaction on the rubber surface, and the precipitation of its hydrates improved the rubber crumb-cement paste interface56, leading to an augmentation of the compressive strength.

However, SL of 30% specimen reduced the strength by 11.97%. When too much LS is doped, too little cement is doped to produce only a small amount of CH, which is not enough to efficiently stimulate the volcanic ash reaction of LS and thus deteriorate the pore structure33,50. Furthermore, the reduction in cement content caused a decline in the formation of C-S-H, the hydration byproduct of tricalcium silicate and dicalcium silicate. The supplementary C-S-H generated through the volcanic ash-like reaction induced by LS was insufficient to offset this loss, ultimately resulting in a less consolidated structure. Rahman et al.57 found that using 20% LS as supplementary cementitious material produced the maximum strength activity index, which was consistent with the findings obtained from this test. Therefore, the filling effect of excess LS was much lower than the compressive strength enhancement achieved through equal cement hydration, leading to a reduction in concrete strength at higher SL.

Elastic modulus

Table 3 and Fig. 7 exhibit the elastic modulus measurements for LSRC prisms which vary in terms of their SL and SR compositions. The trend in the elastic modulus as it relates to alterations in SL and SR closely mirrored the trend observed for compressive strength, but was more significantly affected by SR. Compared with L0R0, the elastic modulus of the specimens increased by 3.2% when only 10% of LS was added and decreased by 23.62% when only 10% of rubber was added.

The elastic modulus of concrete decreased as SR increased, and grew and later diminished with increasing SL. When SL was 10% (Group 2), the elastic modulus of specimens with SR of 5%, 10% and 15% decreased by 20.67%, 22.56% and 35.67%, respectively. It was due to the fact that the rubber itself had a low elastic modulus, markedly inferior to that of the adjacent matrix44,58, which was highly variable58. Similar to the compressive strength, the rubber binds weakly to the cementitious matrix and creates more voids, while the contained impurities interfere with the normal hydration mechanism of the concrete, retarding the emergence of crucial hydration byproducts59,60, thereby contributing to a diminished elastic modulus within the specimen. In addition, when SR was 10% (Group 3), the elastic modulus of specimens with SL of 10% and 20% increased by 4.64% and 6.92% respectively, and with SL of 30% decreased by 6.83%. The elastic modulus of LSRC was substantially influenced by SR, and the mechanism affected by SL was consistent with “Sect. 3.2”.

Peak strain

Table 3 and Fig. 8 exhibit the peak strain measurements for LSRC prisms which vary in terms of their SL and SR compositions. The trend of peak strain as it related to changes in SL and SR followed a similar pattern to that observed in compressive strength, but was more significantly affected by SR. Compared with L0R0, the peak strain of the specimens exhibited an increase of 2.91% when only 10% of LS was added, and decreased by 9.71% when only 10% of rubber was added.

The peak strain of concrete increased as SR increased and grew and later diminished with increasing SL. When SL was 10% (Group 2), the peak strain containing SR of 5%, 10% and 15% decreased by 3.3%, 9.91% and 49.06%, respectively. This was due to the fact that replacing fine aggregate with rubber could provide new modes of energy dissipation such as pullout of rubber particles and internal cracking of rubber61. And rubber had binding action with some of the concrete components62, these inhibited crack propagation as well as segregation of aggregate, leading to an increase in peak strain. When SR was 10% (Group 3), the peak strain with SL of 10% and 20% increased by 3.10% and 17.26% respectively, and with SL of 30% decreased by 0.88%. Consistent with the mechanism analysis above, incorporating an optimal quantity of LS into the concrete mix can effectively fill the voids, resulting in improved compactness and ductility, ultimately enhancing the material’s capacity to withstand deformation. However, an excessive amount of LS led to insufficient hydration, increased pore space, and brittle concrete, which was more prone to rupture11.

Stress-strain curve

As illustrated in Fig. 9(a), the stress-strain curves of LSRC show that the addition of LS alone does not affect the shape of the stress-strain curves too much, but only changes the location of the peak point. Meanwhile, the influence of rubber on the shape of the curve was greater whether it was added separately or in combination.

Figure 9(b) demonstrates the influence of SR on the stress-strain curve when SL is 10%. With SR increasing, the slope of the ascending segment of the stress-strain curve became progressively smaller, while the apex of the curve attained a more gently curved contour. This indicated that rubber particles, due to their good elasticity significantly reduced the initial stiffness of concrete after incorporation, while simultaneously enhancing its ductility63,64. Furthermore, SR exerted a more pronounced influence on the descending portion of the stress-strain curve. As SR escalated, the descending segment of the curve flattened out, leading to a corresponding augmentation in the ultimate strain and a substantial enhancement in the curve’s fullness. This indicated that RC exhibited higher ductility and plastic deformation capacity under axial compression conditions. This flat descending segment implied that the RC was able to withstand greater displacements during the damage process, thus demonstrating a superior energy dissipation capacity.

Figure 9(c) demonstrates the influence of SL on the stress-strain curve when SR is 10%. The different SL had less influence on the overall shape of the curve, and the change in the fullness of the curves was not significant. Specifically, as SL increases, the slope of the ascending portion of the curve, the peak stress and peak strain, exhibit a distinct trend of initially increasing and then subsequently decreasing. In particular, when SL elevated to 30%, the these properties diminished in comparison to standard concrete, owing to the retardation of the cementitious material’s hydration process caused by an abundance of LS content33,50,57. Although the effect of SL on the declining segment of the curve was limited, the peak strain and ultimate strain surpassed those of L0R0 at SL of 10% or 20%. This indicated that the addition of moderate amounts of LS was able to fill in the voids in the concrete, thereby improving its compactness and ductility.

Prediction of axial compressive properties

Calculation of axial compressive performance

By correcting the compressive strength (fc0), elastic modulus (Ec0) and peak strain (εc0) of normal concrete, the prediction equations for compressive strength (fc, LSRC), elastic modulus (Ec, LSRC) and peak strain (εc, LSRC) of LSRC were proposed as follows.

In this paper, the axial compressive performance of LSRC was investigated mainly by considering the effect of SL and SR without fully considering factors such as the source of LS and the shape and size of rubber. Prior investigations have demonstrated that the effect of SR on the axial compressive performance of concrete was more significant, which had led to the creation of various prediction models. Among them, Huang et al.65 proposed a reduction factor (RF) model for concrete with compressive strength up to 600 MPa as shown in Eq. (4). Further, the validation work by Ren et al.66 showed that the model was highly consistent with extensive experimental results (a = 0.281, b = 0.773) within a 95% prediction confidence interval, which fully demonstrated its validity and reliability in practical applications.

where a is a solid material quantity parameter; b is an experimental parameter and SR is the substitution ratio of rubber.

On this basis, a nonlinear fitting method was used to reveal the relationship between the compressive strength reduction factor (RFc), the elastic modulus reduction factor (RFE) and the peak strain reduction factor (RFPS) with SL and SR, as shown in Table 4. Figure 10 illustrates the comparison between the test values for axial compressive properties of the LSRC and the model calculated values. The results showed that they were in good agreement, which fully verified the accuracy of the proposed model.

Proposed stress-strain relations

The determination of the stress-strain relationship is an important step in the nonlinear analysis of concrete structures67. In this study, the model proposed by Guo68 as shown in Eq. (8) was used and the equation was extended to LSRC for the fitting of concrete constitutive model equations under axial compression.

where x = ε /εc, y = σ / fc, a and b are undetermined parameters. Parameter a represents the primary gradient of the dimensionless stress-strain curve, with a lower value indicating a diminished ratio of plastic deformation to the overall deformation achieved at peak stress. Parameter b pertains to the area encompassed beneath the descending segment of the dimensionless stress-strain curve.

The stress-strain relationship of LSRC was obtained experimentally, and the ascending and descending portions of the curves at different SL and SR were fitted using the least squares method. The fitted parameters a and b, and the coefficient of determination (R²), which quantifies the goodness of fit, are presented in Table 5. These values are then incorporated into Eq. (8) to derive the estimated normalized stress-strain curves, as depicted in Fig. 11.

As can be seen from Table 5, the formulas were fitted well. In addition, data regression analyses were carried out on the parameters and the results of the calculations were as follows:

where, fc, LSRC represents the prismatic axial compressive strength of LSRC and its value is determined by Eqs. (1) and (5).

The predicted value of the stress-strain curve was obtained by replacing Eq. (9) into Eq. (8). Comparing the predicted value with both the experimental measurement and the fitted result, as exhibited in Fig. 11, it is observed that the predictive model introduced in this paper demonstrates a remarkable congruency with the empirically observed data, underscoring its high degree of accuracy and consistency.

Conclusion

In this study, the impacts of varying lithium slag substitution ratio and rubber substitution ratio on the axial compressive properties of lithium slag rubber concrete were investigated. On the basis of the experimental data, a prediction formula for the stress-strain correlation in lithium slag rubber concrete was developed. The conclusions that could be drawn as follows:

-

1.

Lithium slag strengthened the inter-aggregate bond and thus increased the crack resistance of the specimen. Rubber can effectively withstand and cushion the load, slow down the crack expansion, and maintain the high integrity of the specimen after compression damage. The combined effects of these two factors resulted in a more complete concrete failure mode with delicate and numerous cracks.

-

2.

The axial compressive properties measured in this paper demonstrated a decreasing trend with the increase of rubber, and an increasing and then decreasing trend with the increase of lithium slag. When 10% of fine aggregate was replaced by rubber, the performance of the cement specimen replaced by 20% of lithium slag was the best, and the axial compressive strength, elastic modulus and peak strain of the specimen were increased by 21.57%, 6.92% and 17.26%, respectively.

-

3.

The incorporation of rubber into concrete resulted in enhanced deformability, whereas the integration of lithium slag effectively mitigated the reduction in axial compressive strength that would otherwise occur due to the introduction of rubber. When 10% of cement was replaced by lithium slag and 5–15% of fine aggregate was replaced by rubber, the peak strain increased by 16.52–44.47% compared with ordinary concrete. When rubber was used to replace 10% of the fine aggregate, the compressive strength was increased by 12.94–21.57% after replacing 10–20% of the cement with lithium slag, and was reduced by 11.97% after replacing 30% of the cement.

-

4.

The influence of lithium slag doping alone on the shape of the curve was limited, mainly by shifting the position of the peak point. In contrast, rubber doping, either alone or in combination, can significantly change the shape of the curve, resulting in a more rounded curve, a flatter descending section, and an increase in ultimate strain.

-

5.

Through regression analysis of the test data, the formulas for the axial compressive properties and the stress-strain model of lithium slag rubber concrete were proposed, which exhibited close agreement with the empirically collected data. The applicability of the model was verified for lithium slag rubber concrete, with a lithium slag substitution ratio of less than 30% and a rubber substitution ratio of less than 15%.

-

6.

These research results indicated that lithium slag rubber concrete possessed good toughness, impact resistance, and durability with minimal loss of strength, and had broad application prospects in the field of structural engineering, such as airports, highways, housing expansion joints, concrete floors, and railway concrete sleepers, among others. This was expected to propel innovative development in the realm of material science and civil engineering.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Arjomandi, A. et al. The effect of sulfuric acid attack on mechanical properties of steel fiber-reinforced concrete containing waste nylon aggregates: experiments and RSM-based optimization[J]. J. Building Eng.64, 105500 (2023).

Hosseini-Poul, S. A. et al. Synergistic effects of GGBFS and EAFS on rheology, mechanical properties, and durability of self-compacting concrete: experiments, predictions, and life cycle assessment[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.437, 136948 (2024).

Nematzadeh, M., Nazari, A. & Tayebi, M. Post-fire impact behavior and durability of steel fiber-reinforced concrete containing blended cement–zeolite and recycled nylon granules as partial aggregate replacement[J]. Archives Civil Mech. Eng.22 (1), 5 (2021).

Hossain, F. M. et al. Mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete containing crumb rubber and polypropylene fiber[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.225, 983–996 (2019).

Tayebi, M. & Nematzadeh, M. Effect of hot-compacted waste nylon fine aggregate on compressive stress-strain behavior of steel fiber-reinforced concrete after exposure to fire: experiments and optimization[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.284, 122742 (2021).

Nematzadeh, M. & Mousavi, R. Post-fire flexural behavior of functionally graded fiber-reinforced concrete containing rubber[J]. Computers Concrete. 27 (5), 417–435 (2021).

Fakoor, M. & Nematzadeh, M. Evaluation of post-fire pull-out behavior of steel rebars in high-strength concrete containing waste PET and steel fibers: experimental and theoretical study[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.299, 123917 (2021).

Wu, H. et al. High-capacity utilization of coal gangue as supplementary cementitious material, geopolymer, and aggregate: a review[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.435, 136857 (2024).

Li, Y., Wu, B. & Wang, R. Critical review and gap analysis on the use of high-volume fly ash as a substitute constituent in concrete[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.341, 127889 (2022).

Liang, J. et al. Effect of high temperature on mechanical properties of lithium slag concrete[J]. Sci. Rep.14 (1), 11872 (2024).

Chen, X. B., Liang, J. F. & Li, W. Compression stress-strain curve of lithium slag recycled fine aggregate concrete[J]. Plos One. 19 (4), e0302176 (2024).

Güneyisi, E. & Gesoğlu, M. Experimental investigation on durability performance of rubberized concrete[J]. Adv. Concrete Constr.2 (3), 193 (2014).

Zhang, Z., Ma, H. & Qian, S. Investigation on properties of ECC incorporating crumb rubber of different sizes[J]. J. Adv. Concr. Technol.13 (5), 241–251 (2015).

Azevedo, F. et al. Properties and durability of HPC with tyre rubber wastes[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.34, 186–191 (2012).

Liu, F. et al. Mechanical and fatigue performance of rubber concrete[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.47, 711–719 (2013).

Nguyen, T. H. et al. Restrained shrinkage cracking in steel fibre reinforced and rubberised cement-based mortars[J]. Mater. Struct.45, 899–904 (2012).

Gupta, T., Chaudhary, S. & Sharma, R. K. Assessment of mechanical and durability properties of concrete containing waste rubber tire as fine aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater.73, 562–574 (2014).

Gupta, T., Sharma, R. K. & Chaudhary, S. Impact resistance of concrete containing waste rubber fiber and silica fume. Int. J. Impact Eng.83, 76–87 (2015).

Gupta, T., Tiwari, A., Siddique, S., Sharma, R. K. & Chaudhary, S. Response assessment under dynamic loading and microstructural investigations of rubberized concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng.29 (8), 04017062 (2017).

Gupta, T. et al. Behaviour of waste rubber powder and hybrid rubber concrete in aggressive environment[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.217, 283–291 (2019).

Nejad, A. & Jahangiri, A. Investigation of the effect of powdered rubber reinforced by different materials on the performance of concrete[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.377, 131067 (2023).

Feng, W. et al. Experimental study on dynamic split tensile properties of rubber concrete[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.165, 675–687 (2018).

Gerges, N. N., Issa, C. A. & Fawaz, S. A. Rubber concrete: mechanical and dynamical properties[J]. Case Stud. Constr. Mater.9, e00184 (2018).

Qiao, D. et al. Potential impact of the end-of-life batteries recycling of electric vehicles on lithium demand in China: 2010–2050[J]. Sci. Total Environ.764, 142835 (2021).

Xiong, H. et al. Study on sintering behavior and properties of lithium slag-based foamed ceramics[J]. J. Non-cryst. Solids. 617, 122499 (2023).

Gao, W. et al. The use of contaminated soil and lithium slag for the production of sustainable lightweight aggregate[J]. J. Clean. Prod.348, 131361 (2022).

Luo, X. et al. Performance characterization and optimization of cement-lithium powder-grain slag composite cementitious materials[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.409, 133851 (2023).

Qin, Y. et al. The mechanical properties of recycled coarse aggregate concrete with lithium slag[J]. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng.2019 (1), 8974625 (2019).

Dong, P. et al. Preparation and study of magnesium ammonium phosphate cement from waste lithium slag[J]. J. Clean. Prod.316, 128371 (2021).

Li, J. & Huang, S. Recycling of lithium slag as a green admixture for white reactive powder concrete[J]. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manage.22 (6), 1818–1827 (2020).

Nematzadeh, M. & Fallah-Valukolaee, S. Effectiveness of fibers and binders in high-strength concrete under chemical corrosion[J]. Structural Engineering and Mechanics, An Int’l Journal, 64(2): 243–257. (2017).

Zhao, K. et al. Experimental and numerical study on chloride transport in cement mortar during drying process[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.258, 119655 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. Corrosion behavior of concrete fabricated with lithium slag as corrosion inhibitor under simulated acid rain corrosion action[J]. J. Clean. Prod.377, 134300 (2022).

Gou, H. et al. A review on Cementitious and Geopolymer composites with Lithium Slag Incorporation[J]. Materials. 17 (1), 142 (2023).

Senin, M. S. et al. A review on the suitability of rubberized concrete for concrete bridge decks[C]//IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. IOP Publishing, 271(1): 012074. (2017).

Khatib, Z. K. & Bayomy, F. M. Rubberized Portland cement concrete[J]. J. Mater. Civ. Eng.11 (3), 206–213 (1999).

JGJ 55-2011. Specification for Mix Proportion Design of Ordinary Concrete (Ministry of Housing and Urban (Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China, 2011).

50081 – 2019, G. B. T. Standard for test methods of concrete physical and mechanical properties, (2019).

Xiao, F., Zhao, P. E. W. & Amirkhanian, S. N. Fatigue behavior of rubberized asphalt concrete mixtures containing warm asphalt additives[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.23 (10), 3144–3151 (2009).

Li, D. et al. Compressive stress strain behavior of crumb rubber concrete (CRC) and application in reinforced CRC slab[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.166, 745–759 (2018).

Hameed, A. S. & Shashikala, A. P. Suitability of rubber concrete for railway sleepers[J]. Perspect. Sci.8, 32–35 (2016).

Turatsinze, A. & Garros, M. On the modulus of elasticity and strain capacity of self-compacting concrete incorporating rubber aggregates[J]. Resour. Conserv. Recycl.52 (10), 1209–1215 (2008).

Huang, Z. et al. Effect of rubber particles and fibers on the dynamic compressive behavior of novel ultra-lightweight cement composites: Numerical simulations and metamodeling[J]. Compos. Struct.258, 113210 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Performance enhancement of rubberised concrete via surface modification of rubber: a review[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.227, 116691 (2019).

Aslani, F. Mechanical properties of waste tire rubber concrete[J]. J. Mater. Civ. Eng.28 (3), 04015152 (2016).

Bompa, D. V. et al. Experimental assessment and constitutive modelling of rubberised concrete materials[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.137, 246–260 (2017).

Mohammadi, I., Khabbaz, H. & Vessalas, K. In-depth assessment of Crumb Rubber Concrete (CRC) prepared by water-soaking treatment method for rigid pavements[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.71, 456–471 (2014).

Akinyele, J. O., Salim, R. W. & Kupolati, W. K. The impact of rubber crumb on the mechanical and chemical properties of concrete[J]. Eng. Struct. Technol.7 (4), 197–204 (2015).

Weeks, C., Hand, R. J. & Sharp, J. H. Retardation of cement hydration caused by heavy metals present in ISF slag used as aggregate[J]. Cem. Concr. Compos.30 (10), 970–978 (2008).

He, Z., Li, L. & Du, S. Mechanical properties, drying shrinkage, and creep of concrete containing lithium slag[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.147, 296–304 (2017).

Ayati, B. et al. Acid activated smectite clay as pozzolanic supplementary cementitious material[J]. Cem. Concr. Res.162, 106969 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. A green route to sustainable alkali-activated materials by heat and chemical activation of lithium slag[J]. J. Clean. Prod.225, 1184–1193 (2019).

Donatello, S., Tyrer, M. & Cheeseman, C. R. Comparison of test methods to assess pozzolanic activity[J]. Cem. Concr. Compos.32 (2), 121–127 (2010).

Celik, K. et al. High-volume natural volcanic pozzolan and limestone powder as partial replacements for Portland cement in self-compacting and sustainable concrete[J]. Cem. Concr. Compos.45, 136–147 (2014).

He, Z. et al. Hydration and microstructure of concrete containing high volume lithium slag[J]. Mater. Express. 10 (3), 430–436 (2020).

Onuaguluchi, O. Effects of surface pre-coating and silica fume on crumb rubber-cement matrix interface and cement mortar properties[J]. J. Clean. Prod.104, 339–345 (2015).

Rahman, S. M. A. et al. Assessment of lithium slag as a supplementary cementitious material: pozzolanic activity and microstructure development[J]. Cem. Concr. Compos.143, 105262 (2023).

Meddah, A., Beddar, M. & Bali, A. Use of shredded rubber tire aggregates for roller compacted concrete pavement[J]. J. Clean. Prod.72, 187–192 (2014).

Kabeer K I S A, Vyas, A. K. Utilization of marble powder as fine aggregate in mortar mixes[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.165, 321–332 (2018).

Siddika, A. et al. Properties and utilizations of waste tire rubber in concrete: a review[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.224, 711–731 (2019).

Reda Taha, M. M. et al. Mechanical, fracture, and microstructural investigations of rubber concrete[J]. J. Mater. Civ. Eng.20 (10), 640–649 (2008).

Thomas, B. S., Gupta, R. C. & Panicker, V. J. Recycling of waste tire rubber as aggregate in concrete: durability-related performance[J]. J. Clean. Prod.112, 504–513 (2016).

Ganjian, E., Khorami, M. & Maghsoudi, A. A. Scrap-tyre-rubber replacement for aggregate and filler in concrete[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.23 (5), 1828–1836 (2009).

Najim, K. B. & Hall, M. R. Crumb rubber aggregate coatings/pre-treatments and their effects on interfacial bonding, air entrapment and fracture toughness in self-compacting rubberised concrete (SCRC)[J]. Mater. Struct.46, 2029–2043 (2013).

Huang, W. et al. Strength reduction factor of crumb rubber as fine aggregate replacement in concrete[J]. J. Building Eng.32, 101346 (2020).

Ren, F. et al. Crumb rubber as partial replacement for fine aggregate in concrete: an overview[J]. Constr. Build. Mater.343, 128049 (2022).

Fallah-Valukolaee, S. & Nematzadeh, M. Experimental study for determining applicable models of compressive stress–strain behavior of hybrid synthetic fiber-reinforced high-strength concrete[J]. Eur. J. Environ. Civil Eng.24 (1), 34–59 (2020).

Guo, Z. H. & Zhang, X. Q. Experimental investigation of stress-strain curves for concrete. J. Building Struct.3 (1), 1–12 (1982). (In Chinese).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the financial support provided by the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (No. 52068001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.K.: wrote the main manuscript text, visualization; L.J.: revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, visualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition; W.C.: software, validation; W.X.:visualization, Software; L.J.: investigation, visualization, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, K., Liang, J., Wang, C. et al. Axial compression stress-strain relationship of lithium slag rubber concrete. Sci Rep 14, 23037 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73566-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73566-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Mechanical Performance and Sustainability of Rubberized Self-Compacting Concrete as a Repair Material: Insights from Bond Strength and Life Cycle Assessment

Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering (2026)

-

Adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system optimization of natural rubber latex modified concrete’s mechanical Properties

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Mechanical properties of steel fiber-reinforced rubber concrete after elevated temperature

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

ANFIS modelling of the strength properties of natural rubber latex modified concrete

Discover Applied Sciences (2025)