Abstract

The utilization of visible-near infrared (Vis–NIR) spectroscopy presents a nondestructive, fast, reliable and cost-effective approach to predicting total nitrogen (TN) and organic carbon (OC) levels. This study employed a combination of Vis–NIR spectroscopy, partial least-squares regression (PLSR), and support vector machine (SVM) models to investigate the effects of mining on TN and OC stocks in both the topsoil (0–10 cm) and subsoil (10–40 cm). 105 soil samples were collected from agricultural areas near an iron mine, polluted, moderately-polluted, and non-polluted sites. Results indicated that soils at the non-polluted site had the highest of soil OC stocks (7.5 kg m–2) and total nitrogen (2.5 kg m–2), followed by the moderately-polluted site. Furthermore, it was observed that soils from the polluted site displayed the highest spectral reflectance. The spectral bands in the range of 500–700 nm showed the strongest correlation with soil organic carbon content. Notably, the SVM method utilizing Vis–NIR spectroscopy provided superior predictions for both subsoil and topsoil organic carbon and total nitrogen compared to the PLSR methods. Additionally, SVM demonstrated better performance in predicting topsoil soil organic carbon (R2 = 0.87, RMSE = 0.13%, and RPD = 2.8) and total nitrogen (R2 = 0.91, RMSE = 0.13%, and RPD = 2.4) compared to the subsoil, owing to the larger OM content in the topsoils.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soil organic carbon (SOC) is considered as the largest OC reservoir in terrestrial ecosystems and the potential for SOC accumulation is crucial for maintaining soil health and mitigating climate change1,2,3. Its significance in mitigating climate change and environmental and human health-risks has garnered substantial attention, as it is a primary dynamic carbon stock within terrestrial systems4,5. Similarly, soil total nitrogen (TN) is essential for maintaining a healthy ecological balance, being a vital constituent of organic matter and a key player in the soil’s mineralization process6.

Human activities, especially mining, have had widespread and significant impacts on both TN and SOC worldwide7,8. Generally, mining operations involve extensive removal of vegetation, extensive clearing of land, and permanent changes in natural soil structure These factors lead to decreased soil fertility, soil structure instability, and significant losses of TN and SOC, which are critical to maintaining good soil health and ecological functions9. Degradation of these important soil elements not only affects local ecosystems but also contributes to broader environmental challenges, such as increased soil loss, decreased water holding capacity, and greenhouse gas emissions. This highlights the urgent need for effective and accurate methods for monitoring the extent of soil degradation 01710. In particular, methods that can rapidly and cost-effectively monitor changes in TN and SOC concentrations to create sustainable land reclamation and land management practices in mine-affected areas are needed.

Traditional methods of carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) measurements methods are often costly and time-consuming11. The advent of visible and near-infrared (Vis–NIR) soil spectroscopy offers a promising alternative. This rapid, cost-effective, and non-destructive technique leverages distinctive spectral characteristics to provide valuable insights into the composition and structure of different molecules, facilitating the quantification of C and N content in soils12,13,14.

Soil spectroscopy is a powerful tool for monitoring soil health, structure and productivity. This method is non-destructive, that is, it does not destroy soil or plants, and it is efficient and fast, making it a valuable method for agricultural applications. Recent research highlights the widespread application of soil analysis, especially in identifying sustainable management options15,16,17,18. For example, it can be used to improve crop yields by rapidly assessing soil nutrition and health, help farmers make informed crop and crop management decisions and play a key role in monitoring soil quality over time. A notable example is Ramírez-Rincón et al.19, who demonstrated a strong correlation (r > 0.85) between soil spectrum and OC in Colombian agricultural soils. This finding highlights the potential of soil spectroscopy for measuring SOC.

Traditional statistical methods cannot adequately deal with extensive datasets20. Hence, over the years, data-mining methods have evolved for the estimation of soil properties from spectral data. The partial least squares regression (PLSR) is renowned for its accuracy with extensive datasets, frequently employed for the estimation soil properties such as carbon, nitrogen, and clay21,22,23,24,25,26. In addition, non-linear machine learning algorithm like support vector machines (SVM), a pattern search and grid search algorithms, offer robust alternatives, particularly for complex datasets that combine multiple sites from diverse geo-pedological areas27,28,29. Pattern search and grid search algorithms explore a broad range of parameter configurations and evaluate a predefined set of parameter values, respectively, both contributing to effective model optimization. Studies such as those by Seema et al.30 have reported the performance of PLSR and SVM methods for the SOC estimation using Mid-infrared (MIR) spectroscopy. Xiao et al.31 has focused on the prediction of soil organic matter (SOM) using spectroscopy in mining areas to address soil pollution, while Wang et al.32 used of Vis–NIR spectra for predicting soil salinity under various land uses. These findings showed the versatility and accuracy of spectroscopy for the assessment of soil properties.

Despite these advancements, there remains a significant knowledge gap regarding the specific impact of iron mining on SOC and TN, particularly in subsoil. Understanding these impacts is crucial for the development of effective soil management strategies in mining-affected regions. Thus, the main objective were to: (1) investigate the effects of an iron mine on both subsoil and topsoil OC and TN content and stocks in polluted, moderately polluted, and no-polluted sites in western Iran, and (2) use of Vis–NIR spectroscopy combined with advanced machine-learning algorithms, PLSR and SVM, to provide a comprehensive assessment of topsoil and subsoil OC and N in mining-impacted areas, addressing the critical knowledge gap in this field.

Method and materials

Study area

This research was conducted in the southern part of Malayer, Hamaden Province, Iran. The study area is situated between 34°11ʹ and 34°7ʹ N and 49°03ʹ–48°56ʹ E. The study site has a semi-arid climate with a mean rainfall of 320.0 mm. The mean annual temperature is 14.5 °C, ranging from − 10 °C in winter to 41 in summer °C. During the warm months (Jun to August) temperatures are quite high and during winter (December to March), temperatures are relatively low. Soils have high amount of calcium carbonate and on the basis of the Taxonomy classification33, soils are classified as Entisols, Alfisols, and Inceptisols. Lands are commonly used for livestock and agriculture, mainly for potatoes, barley, wheat, and, with some areas dedicated to horticulture. Geological formations include intermountain depressions, mountain ranges, and various types of sedimentary basins.

Soil sampling and analysis

105 soil samples were collected from agricultural lands, as depicted in Fig. 1. In order to ensure unbiased results, the soil samples were randomly collected from three sites, with 45 samples obtained from each site. These sites consisted of a polluted site located near the mine, a moderately-polluted site, and a no-polluted site. To ensure accuracy and reliability, three replicate soil samples were taken at each sampling point to a depth of 40 cm using a stainless-steel auger. After soil sampling, the samples were divided into two depths: 0–10 cm (topsoil) and 10–40 cm (subsoil). The three topsoil samples from each sampling location were combined to create a homogeneous topsoil sample, and the three subsoil samples were similarly combined to create a homogeneous subsoil sample. The samples were transferred to the lab and air-dried, then ground and sieved prior to soil physicochemical soil analysis. Soil texture was determined using a hydrometer. Organic matter (SOM) was determined based on the Walkley–Black by oxidizing organic matter with potassium dichromate and determining the amount of carbon that was present based on the unreacted dichromate34. While total N was determined based on the Kjeldahl approach by converting organic nitrogen into ammonia, distilling it, and then quantifying it through acid–base titration35. The calcium carbonate (CaCO3) content was obtained by utilizing a 1 mol L–1 HCl, reacting the soil with the HCl to dissolve the CaCO3, and then measuring the amount of carbon dioxide released during the reaction. CaCO3 content is calculated based on the volume of acid used and the amount of CO2 evolved34. Additionally, an EC-pH meter was utilized for determining the soil’s electrical conductivity (EC) and pH values.

A screenshot of Google Earth-map of the studied sites and sampling positions36.

Soil spectroscopy

Vis–NIR spectra were collected in a darkroom using an ASD FieldSpec3 spectrometer (350–2500 nm). A 50 W halogen lamp, placed 10 cm from the soil sample at a 30° angle, provided the light sourceAn optical probe was positioned 5 cm above the sample for a 1° field angle, with a 100% reflectance white panel used as the reference for accurate spectral reflectance. Fifteen spectral were measured for each soil sample. The final reflectance spectrum was obtained by excluding five noisy spectra and averaging the results of the remaining ten. The splicing correction function in ViewSpecPro software (version 6.0.0, ASD Inc, CO, USA) was employed to correct for discrepancies between different spectral data segment. To improve accuracy and minimize baseline shifts, the reflectance spectra were converted to absorbance using A = log(1/R), followed by Savitzky-Golay filtering. These pre-processing steps were implemented in Python (version 3.8.5) for efficient data processing.

Model development and validation

The spectral differences among various sites were analyzed and visually represented using Principal Component Analysis (PCA). The PCA utilized a correlation matrix to extract meaningful insights from the data. The statistical software R (2013) was employed to facilitate effective visualization of the results. Cross-validation was used to evaluate the effectiveness of the pre-processing methods. The dataset was split into 70% for calibration and 30% for validation, utilizing the k-means algorithm for partitioning.

To enhance the connection between soil data and Vis–NIR spectra, Partial Least-Squares Regression (PLSR) was employed. The PLSR is a powerful tool specifically designed to handle large datasets with high multicollinearity among predictor variables, such as soil spectra data. It identifies latent variables highly correlated with the target response variables, optimizing the covariance between the spectral data and soil properties. This process compresses the data matrix, reducing dimensionality and capturing the most relevant information. Consequently, a robust model is created that can accurately predict soil properties based on the given Vis–NIR spectra. Through decomposition into factor scores and factor loadings, the PLSR model predicts the response variable Y by identifying the most critical variation in the predictor variable X. The quantity of inputs utilized during model development plays a crucial role in determining the accuracy of predictions; including too few or too many principal components can lead to under-fitting or over-fitting, resulting in poor predictive performance. The most accurate regression equations were obtained by selecting the parameters that yielded the best results for predicting TN and OC. The PLSR was perfprmed using Unscrambler × 10.337.

To identify the optimal prediction, the SVM models were trained using a repeated 10-k-fold cross-validation approach that incorporated all spectral pre-processing techniques. To enhance the performance of this process, an automated grid search was implemented to optimize the SVM hyperparameters, which were varied within the range of 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, and 100. A test-set validation was then conducted to evaluate the models’ performance. We utilized the Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel to model complex relationships in data due to its ability to handle non-linear relationships. The calibration set, consisting of 73 samples, was used to assess the results of PLSR and SVM. Subsequently, the optimal PLSR model, determined through cross-validation, was applied to the validation set containing 32 samples to evaluate the accuracy of the models.

Data analyses were performed using Statistica 8.0 software, and Excel 2016 was utilized for generating graphs. To evaluate the data normality, a Kolmogorov and Smirnov test was performed Statistica 8.0 software. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to investigate the impacts of mining on STN and OC stocks. Furthermore, an Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test was conducted to compare the different sites. Additionally, a Pearson index was used to assess the associations between TN and OC stocks in the topsoil and subsurface layers. Some indicators were employed to statistically evaluate the models, including R2, RMSE, ME, and RPD ratio (predicted deviation).

where n represents the observations number, O denotes the observed values, P represents the predicted values, Sd signifies the standard deviation, and SEP represents the standard error. The estimations were assessed based on the criteria suggested by Viscarra-Rossel38 as follows: “Excellent” estimations are characterized by an RPD ≥ 2.5 and an R2 ≥ 0.80.“Good” estimations have an RPD between 2 and 2.5 and an R2 of at least 0.70. “Moderate” estimations range from an RPD of 1.5 to 2 and an R2 of ≥ 0.60. “Poor” estimations have an RPD < 1.5 and an R2 < 0.60.

Results and discussion

Descriptive of soil samples

Table 1 provides an overview of the soil properties across three studied sites; polluted, moderately polluted, and no-polluted sites. Soils with a mean pH greater than 7.6 are classified as calcareous and alkaline, likely due to a higher content of CaCO3 (mean CaCO3 = 45.9%; see Table 1). The sits exhibit a vast range of particle sizes, with clay ranging from 8.5% to 57.2%, sand from 5.7 to 66.5%, and silt from 15.5 to 66.4%. The soil texture across the study area exhibits a range from clay to sandy loam, with the predominant soil classifications being clay loam and loam (Fig. 2).

As shown in Fig. 3, both the validation and calibration datasets had similar soil texture classes. Soils classified moderately polluted soils and no-polluted soils showed a higher average clay compared to polluted soils. Among the factors examined, clay content displayed the greatest variability, with a coefficient of variation (CV) value of 33.2%. In terms of TN and OC, the topsoil in no-polluted soils land had higher levels compared to moderately-polluted and polluted soils. Similarly, the subsurface in no-polluted exhibited greater OC and TN compared to moderately-polluted and polluted soils. Although top and subsoil and C and TN in moderately-polluted were greater than those in polluted soils, these differences were not statistically significant.

Table 2 presents the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) values for the soil profile (0–40 cm) TN and OC in relation to various soil basic properties. Among the soil particles, clay exhibited the highest positive correlation with SOC (r = 0.38, p < 0.05) and TN (r = 0.31, p < 0.05). Additionally, a positive significant correlation was found between organic matter (OM) and CaCO3 (r = 0.37, p < 0.05), which is in the line with the findings of Ref.39, Ostovari et al.40 who reported r = 0.36 between OM and CaCO3. The CaCO3 contains a substantial amount of Ca2+ ions, playing a vital act in the formation of large and stable soil aggregates. It acts as a binding agent, promoting the flocculation of soil minerals41,42. This leads to a reduction in TN and OC loss and enhances the resistance of soil aggregates against runoff and raindrop detachment.

STN and OC stocks in three studied sites

Among the three soil groups, non-polluted soils had the greatest stocks of SOC (7.4 kgm–2) and TN (2.4 kgm–2) in the 0–40 cm depth range, moderately-polluted soils followed closely behind. Significant differences were observed in TN and OC stocks between the no-polluted and polluted soils. But the difference between moderately-polluted and polluted soils was not statistically significant. Agricultural soils have significantly lower SOC stocks compared to orchard soils. No-polluted soils benefit from high inputs of C from litter and extensive fine root systems, contributing to the greater OC accumulation in the soil profile. Additionally, no-polluted soils generally possess higher vegetation and root density compared to polluted soils, directly affecting soil porosity and indirectly influencing the distribution of SOC through processes like illuviation, percolation, faunal, and activities.

The conversion of agricultural land to mining results in the decrease of soil organic carbon, while reversing this land use change can lead to an accumulation SOC content. The primary factor influencing SOC stocks is the presence of vegetation, which contributes significantly through the increase of root biomass and the addition of plant residues. Vegetation litter plays a crucial role for determining both the quantity and quality of SOC. Furthermore, well-developed roots systems enhance soil aggregation and promote the accumulation of SOC, creating a healthier soil environment.

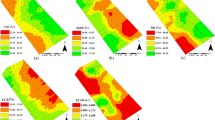

As depicted in Fig. 3, the no-polluted soils exhibited higher stocks of TN and OC in both the subsoil and topsoil, with moderately-polluted ranking second. Notably, approximately 50% of the SOC stocks are located in the subsoil across the all three sites, as shown in Fig. 4a and b. In contrast, more than 70% of the total nitrogen (TN) is concentrated in the topsoil. This distribution indicates that the high levels of total nitrogen (TN) and organic carbon (OC) observed in the subsoil across three sites (as shown in Fig. 4) could result in a significant underestimation of TN and soil organic carbon (SOC) if assessments are restricted to shallower soil layers.

This phenomenon may be attributed to the higher nitrogen inputs received by the topsoil from various sources, such as fertilizer application or nitrogen fixation by vegetation, compared to the subsurface layers. The presence of high subsurface SOC stocks in mountainous regions, like our study site, can be explained by the inhibiting effects of low temperatures and abundant precipitation, which slow down the SOC decomposition and promote its accumulation at higher elevations43. These results align with the findings of Lozano-García et al.44 and Patton et al.45, who reported 51% and 41% of the SOC were found below depths of 30 cm and 25 cm, respectively. Additionally, Wiesmeier et al.46 pointed out that a significant portion of SOC (ranging from 20 to 47%) is present in German subsoil. Furthermore, Lozano-García et al.44 and also Yimer et al.47 noted that 41% and 51% of TN were located within depth of 0–25 cm. Similarly, Bangroo et al.48 found comparable ranges of TN stocks, with 59–62% in the depth range of 0–20 cm and 41–38% in the depth range from 20 to 60 cm in the Himalayan.

Soil Vis–NIR spectroscopy

Figure 5 illustrates the relationship of TN and SOC contents and spectral reflectance. SOC were significantly linked with several bands: 490 (r = 0.23), 671 (r = 0.35), 785 (r = 0.24), 1090 (r = − 0.26), 1420 (r = 0.34), 1860 (r = − 0.33), and 2422 nm (r = 0.33). Babaeian et al.49 monstrated correlations of SOM with bands near 490, 1400, 1860, 2340, and 2440 nm. Additionally, Martin et al.50 and Stenberg51 have reported the usability of similar bands for SOM prediction. Udelhoven et al.52 emphasized the importance of brightness of soil sample in the visible region for predicting SOM.

Absorptions in NIR (780–2500 nm) can be attributed to the overtones bands resulting from the bending and stretching of C–H, C–O, and N–H groups53, as well as the overtones of OH, SO4–2, and CO3–2 groups. These vibrations are contributed to the absorptions observed in the Vis–NIR region. Islam et al.54 highlighted that the visible region may provide a better estimation of SOM. Figure 6 reveals a pattern in the reflectance of the TN and SOC. Notably, these properties exhibit a similar trend, showing a robust correlation (r = 0.68, p < 0.01) between them. Furthermore, TN shows also significant correlations with some wavelengths, including 542 nm, 615nm, 1445 nm, and 2343 nm.

Figure 6 reveals distinct bands in the wavelength range of 600 to 700 nm, as well as four well-defined bands at 1415, 1990, 2222, and 2342 nm. These findings support the idea that SOC influences spectral data across from 701 to 2445 nm, as noted by Stenberg et al.51. Additionally, Tahmasbian et al.55 emphasized the significance of specific wavelengths, particularly the regions from 740 to 800 nm and from 900 to 1000 nm, which are crucial for predicting SOC and total nitrogen (TN) content, respectively. Notable absorption features are also observed around 950 nm and within the 2300–2445 range nm, further supported by Babaeian et al.49.

The mean soil spectra for three soil groups (polluted soils, moderately polluted soils, and no-polluted soils) are presented in Fig. 6a. The no-polluted soils, characterized by higher OC in both subsoil and topsoil, display the lowest spectra reflectance, followed by moderately polluted soils, and no-polluted soils. Soil spectra are influenced by landuse changes, primarily due to their significant effect on SOM, a crucial soil property that impacts soil color.

Consequently, these alterations have significant effects on soil spectra through their influence on SOM39,55. Higher spectra observed in the polluted soils could be attributed to their predominance in high-altitude and high-steep slope areas, where lower vegetation cover increases the risk of erosion. There is a direct correlation between slope and soil water content, which significantly influences the accumulation of SOC. Slope affects SOC accumulation by influencing the infiltration and retention of water in the soil56. Vegetation growth is adversely affected on steep slopes, leading to a significant decrease in soil fertility and, consequently, SOC stocks57. Previous studies have consistently shown that the SOC content tends to be higher on lower slopes (non-polluted soils) and lower on upper slopes, where intense sunlight leads to high rates of water evaporation, resulting in relatively low soil water content56,57. This condition promotes the decomposition of SOC. Moreover, the upper slopes are more prone to soil erosion, leading to the deposition of eroded soil on the lower slopes. Consequently, the soil profile in the lower slopes becomes relatively thicker, increasing SOC stock. At the polluted site, especially near the mine areas, pollutant deposits and dust from the mine reduce plant growth and vegetation density, resulting in a significant reduction in SOC. Areas with less vegetation cover are more prone to erosion and degradation, leading to uneven distribution of SOC.

Figure 6b demonstrates that topsoil exhibits lower spectra compared to the subsoil. This difference can be attributed to the darker nature of topsoil, which typically contains larger stocks of soil organic matter derived from various sources such as exudates, root litter, plant residues, and ground litter. Correspondingly, studies by Stenberg51 identified absorption at 480, 580 and 650 nm, which are linked to oxides (e.g. hematite) that influence soil color. These findings align with those of Babaeian et al.49, further supporting the identified features. Sandy soil exhibits the highest reflectance, primarily due to its composition of white minerals like quartz and potassium-feldspar. In contrast, the clay-texture soil showed the lowest spectral (Fig. 6c). Bowers and Hanks58 observed a reduction in reflectance as particle size increased. Additionally, the soil spectra within the 700 to 2450 nm range is significantly influenced by soil texture, particularly in relation to distinct absorption features.

Model development and validation

In Fig. 7, the comparison between predicted and measured OC and total TN contents in both subsoil and topsoil using SVM and PLSR models with soil spectra is presented..

Both SVM and PLSR methods demonstrate high accuracy in predicting TN and OC, as evidenced by the excellent distribution of TN and SOC data points around the 1–1 lines in both calibration and validation datasets (Fig. 7). Table 3 further supports the superior performance of SVM and PLSR for topsoil TN and OC compared to subsoil TN and OC in both datasets. This can be attributed to the higher reflectance of the topsoil, which is associated with higher TN and OC. Topsoil generally exhibits higher reflectance due to its greater SOM, which improves the accuracy of spectral models like SVM and PLSR59. For both subsoil and topsoil, the SVM method shows excellent prediction results. Specifically, for OC, SVM achieves R2 values of 0.91 and 0.88, RMSE values of 0.12% and 0.13%, and RPD ratios of 2.8 and 2.4, respectively (Table 3). Similarly, for TN, SVM achieves R2 = 0.88 and 0.82, RMSE = 0.13% and -0.21%, and RPD ratios of 2.4 for both subsoil and topsoil. In comparison, PLSR performs well with R2 = 0.82 for both TN and OC in the topsoil but slightly underestimates the TN and OC content in both subsoil and topsoil. Interestingly, scholars from various countries have conducted a series of studies on the monitoring SOC60. Seema et al.30 found that the PLSR model with R2 = 0.78, RMSE = 0.04%, and RPD = 2.07 outperformed the SVR model (R2 = 0.65, RMSE = 0.09%, and RPD = 1.12) for predicting SOC content. This underscores the reliability of MIR spectroscopy for SOC determination and highlights the importance of selecting appropriate techniques and methods for spectral analysis. Xiao et al.31 utilized spectroscopy to assess SOM in mining areas, achieving a strong correlation coefficient (r) of 0.96 and a relative percentage deviation (RPD) of 3.08, further demonstrating the effectiveness of spectroscopy for precise SOM evaluation in mined regions.

Several studies have highlighted the effectiveness of advanced models like SVM and PLSR in predicting soil carbon and nitrogen content. Tahmasbian et al.55 reported satisfactory results with low RMSE and high R2 when using advanced models in predicting OC and TN in soil. Yang et al.61 emphasized the high performance of the PLSR in predicting SOC. Ding et al.62 demonstrated that SVM produced the best results for SOC prediction and highlighted the benefits of combining Vis–NIR spectroscopy and SVM for monitoring and predicting SOC in arid region. Jia et al.63 used Vis–NIR and MIR techniques for predicting SOC under different land cover types, and found that SVM regression models outperformed PLSR models in predicting SOC concentration. Viscarra-Rossel and Behrens64 compared various data mining techniques and concluded that SVM was the best approach for estimating SOC, %clay, and pH by using soil Vis–NIR spectroscopy. Sorenson et al.26 suggested that Vis–NIR soil spectroscopy integrated with other methods can be successfully analyzed the variability of TN and OC at soil aggregate scales. In summary, SVM and PLSR models demonstrate strong predictive capabilities for estimating TN and OC using soil spectra. Their accuracy makes them valuable tools for efficiently monitoring and prediction of soil properties.

Higher organic carbon (OC) content in topsoil leads to better predictions with support vector machines (SVM) compared to partial least squares regression (PLSR) due to SVM’s ability to capture complex, non-linear relationships and handle high-dimensional data effectively. The distinctive spectral features associated with high OC content provide rich data that SVM can leverage for more accurate predictions. In contrast, PLSR’s linear approach and dimensionality reduction can miss the nuanced spectral variations in high-OC soils, limiting its predictive power65.

Conclusion

The study aimed to investigate the effects of mining on total nitrogen (TN) and organic carbon (OC) stocks in both the topsoil and subsoil across 3 sites (polluted, moderately-polluted, and non-polluted) using Vis–NIR spectroscopy coupled with SVM and PLSR models. The findings revealed crucial insights into soil health, with the non-polluted site showing the highest levels of organic carbon (7.5 kg m–2) and total nitrogen (2.5 kg m–2), indicating a healthier soil environment. The moderately-polluted site had lower but still significant levels of TN and OC, while the polluted site, especially in northern areas, exhibited the highest spectral reflectance, suggesting that pollution from the iron mine has significantly affected soil properties. Reflectance in the 500–700 nm range was strongly correlated with OC, while the 175–1950 nm range was more strongly correlated to TN. The study also found that using the SVM method with Vis–NIR spectroscopy improved the accuracy of soil property predictions compared to PLSR methods. SVM was particularly effective in predicting topsoil and subsoil TN and OC due to its ability to handle higher concentrations of organic matter. These findings provide a deeper understanding of the impact of iron mining pollution on soil properties at different depths and highlight the benefits of advanced predictive methods in soil science.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Batjes, N. H. Total carbon and nitrogen in the soils of the world. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 65(1), 10–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejss.12114_2 (2014).

Du, C., Xu, Z., Yi, F., Gao, J. & Shi, K. Bearing capacity mechanism of soil bagged graphite tailings. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 83(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-023-03531-7 (2023).

Qiu, S. et al. Carbon storage in an arable soil combining field measurements, aggregate turnover modeling and climate scenarios. Catena 220, 106708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2022.106708 (2023).

Adhikari, K. & Hartemink, A. E. Linking soils to ecosystem services—A global review. Geoderma 262, 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2015.08.009 (2016).

Pei, T. et al. Mapping soil organic matter using the topographic wetness index: A comparative study based on different flow-direction algorithms and kriging methods. Ecol. Indic. 10(3), 610–619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2009.10.005 (2010).

Gregory, A. S. et al. An assessment of subsoil organic carbon stocks in England and Wales. Soil Use Manag. 30(1), 10–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/sum.12085 (2014).

Ussiri, D. A. N., Jacinthe, P. A. & Lal, R. Methods for determination of coal carbon in reclaimed minesoils: a review. Geoderma 214, 155–167 (2014).

Zhang, T. et al. Effects of coastal wetland reclamation on soil organic carbon, total nitrogen, and total phosphorus in China: A meta-analysis. Land Degrad. Dev. 34(11), 3340–3349. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.4687 (2023).

Shrestha, R. K. & Lal, R. Changes in physical and chemical properties of soil after surface mining and reclamation. Geoderma 161, 168–176 (2011).

Poppiel, R. R. et al. High resolution middle eastern soil attributes mapping via open data and cloud computing. Geoderma 385, 114890 (2021).

Demattê, J. A. M., Dotto, A. C., Bedin, L. G., Sayão, V. M. & Souza, A. B. Soil analytical quality control by traditional and spectroscopy techniques: constructing the future of a hybrid laboratory for low environmental impact. Geoderma 337, 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.09.010 (2019).

Nawar, S., Buddenbaum, H., Hill, J., Kozak, J. & Mouazen, A. M. Estimating the soil clay content and organic matter by means of different calibration methods of VIS–NIR diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. Soil Till. Res. 155, 510–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2015.07.021 (2016).

Nawar, S. & Mouazen, A. M. Comparison between random forests, artificial neural networks and gradient boosted machines methods of on-line Vis-NIR spectroscopy measurements of soil total nitrogen and total carbon. Sensors 17, 2428. https://doi.org/10.3390/s17102428 (2017).

Rizzo, R., Demattê, J. A., Lepsch, I. F., Gallo, B. C. & Fongaro, C. T. Digital soil mapping at local scale using a multi-depth Vis-NIR spectral library and terrain attributes. Geoderma 274, 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.03.019 (2016).

Hong, Y. et al. Improving spectral estimation of soil inorganic carbon in urban and suburban areas by coupling continuous wavelet transform with geographical stratification. Geoderma 430, 116284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2022.116284 (2023).

Salehi-Varnousfaderani, B., Afshin Honarbakhsh, A., Tahmoures, M. & Akbari, M. Soil erodibility prediction by Vis-NIR spectra and environmental covariates coupled with GIS, regression and PLSR in a watershed scale, Iran. Geoderma Reg. 28, e00470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geodrs.2021.e00470 (2022).

Vasques, G. M., Grunwald, S. & Sickman, J. O. Comparison of multivariate methods for inferential modeling of soil carbon using visible/near infrared spectra. Geoderma 146, 14–25 (2008).

Wijewardane, N. K., Ge, Y., Wills, S. & Libohova, Z. Predicting physical and chemical properties of US soils with a mid-infrared reflectance spectral library. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 82, 722–731. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2017.10.0361 (2018).

Ramírez-Rincón, J. A., Manuel Palencia, M. & Combatt, E. M. Determining relative values of pH, CECe, and OC in agricultural soils using functional enhanced derivative spectroscopy (FEDS0) method in the mid-infrared region. Infrared Phys. Technol. 133, 104864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infrared.2023.104864 (2023).

Zhao, Z. et al. Identification of geochemical anomalies based on RPCA and multifractal theory: A case study of the Sidaowanzi area, Chifeng, Inner Mongolia. ACS Omega 9(23), 24998–25013. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.4c02078 (2024).

Khayamim, F. et al. Using visible and near-infrared spectroscopy to estimate carbonates and gypsum in soils in arid and subhumid regions of Isfahan, Iran. J. Near Infrared Spectrosc. 23, 155–165 (2015).

Santra, P. et al. Estimation of soil hydraulic properties using proximal spectral reflectance in visible, near-infrared, and shortwave-infrared (VIS-NIR-SWIR) region. Geoderma 152, 338–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2009.07.001 (2009).

Stevens, A., Nocita, M., Tóth, G., Montanarella, L. & van Wesemael, B. Prediction of soil organic carbon at the European scale by visible and near infrared reflectance spectroscopy. PLoS One 8, e66409. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066409 (2013).

Nawar, S. & Mouazen, A. M. On-line vis-NIR spectroscopy prediction of soil organic carbon using machine learning. Soil Till. Res. 190, 120–127 (2019).

Bo, Y. B., Yan, C., Yuan, J., Ding, N. & Chen, Z. Prediction of soil properties based on characteristic wavelengths with optimal spectral resolution by using Vis-NIR spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 293, 122452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2023.122452 (2023).

Sorenson, P. T., Quideau, S. A. & Rivard, B. High resolution measurement of soil organic carbon and total nitrogen with laboratory imaging spectroscopy. Geoderma 315, 170–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2017.11.032 (2018).

Chen, J. et al. Metallogenic prediction based on fractal theory and machine learning in Duobaoshan area, Heilongjiang province. Ore Geol. Rev. 168, 106030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oregeorev.2024.106030 (2024).

Jiao, S. et al. Hybrid physics-machine learning models for predicting rate of penetration in the Halahatang oil field, Tarim Basin. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 5957. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56640-y (2024).

Wadoux, A.M.-C., Minasny, B. & McBratney, A. B. Machine learning for digital soil mapping: Applications, challenges and suggested solutions. Earth-Sci. Rev. 210, 103359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ear (2020).

Seema, G. A. K., Hati, K. M., Kumar Sinha, N., Mridha, N. & Biswabara, S. Regional soil organic carbon prediction models based on a multivariate analysis of the Mid-infrared hyperspectral data in the middle Indo-Gangetic plains of India. Infrared Phys. Technol. 127, 104372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infrared.2022.104372 (2022).

Xiao, D. et al. Inversion study of soil organic matter content based on reflectance spectroscopy and the improved hybrid extreme learning machine. Infrared Phys. Technol. 128, 104488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infrared.2022.104488 (2023).

Wang, Z., Miao, Z., Yu, X. & He, F. Vis-NIR spectroscopy coupled with PLSR and multivariate regression models to predict soil salinity under different types of land use. Infrared Phys. Technol. 133, 104826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infrared.2023.104826 (2023).

USDA. Soil Survey Staff. Keys to soil taxonomy (11th ed.). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service (2010).

Nelson, D. W. & Sommers, L. E. Total Carbon, Organic Carbon, and Organic Matter. In Methods of Soil Analysis Part 3—Chemical Methods (eds Sparks, D. L. et al.) 961–1010 (Soil Science Society of America, American Society of Agronomy, Madison, WI, 1996).

Bremner, J. M., and Mulvaney, C. S. Nitrogen-total. In "Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 2. Chemical and Microbiological Properties, pp. 595–624 (American Society of Agronomy, Inc., 1982)

Google Inc. (2019). Google Earth Pro (Version 7.3.2) software. https://www.google.com/earth/version/.

Camo Software. The Unscrambler X version 10.3. Camo Software. https://www.camo.com/products/unscrambler/ (2013).

Viscarra-Rossel, R. A. Robust modelling of soil diffuse reflectance spectra by "bagging-partial least squares regression”. J. Near Infrared Spectrosc. 15, 37–47 (2007).

Ostovari, Y. et al. Towards prediction of soil erodibility, SOM and CaCO3 using laboratory VisNIR spectra: a case study in a semi-arid region of Iran. Geoderma 314, 102–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2017.11.014 (2018).

Ostovari, Y., Moosavi, A. A. & Pourghasemi, H. R. Soil loss tolerance in calcareous soils of a semiarid region: Evaluation, prediction, and influential parameters. Land Degrad. Dev. 31(15), 2156–2167 (2020).

Akbari, M. & Azma, M. T. Land capability assessment by combining LESA and GIS in a calcareous watershed, Iran. Arab. J. Geosci. 15, 404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-022-09729-5 (2022).

Mirzaee, S. & Ghorbani-Dashtaki, S. Calibrating the WEPP model to predict soil loss for some calcareous soils. Arab. J. Geosci. 14, 2198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-021-08646-3 (2021).

Baumgarten, A. et al. Organic soil carbon in Austria – Status quo and foreseeable trends. Geoderma 402, 115214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2021.115214 (2021).

Lozano-García, B., Parras-Alcántara, L. & Brevik, E. C. Impact of topographic aspect and vegetation (native and reforested areas) on soil organic carbon and nitrogen budgets in Mediterranean natural areas. Sci. Total Environ. 544, 963–970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.12.022 (2016).

Patton, N. R., Lohse, K. A., Seyfried, M. S., Godsey, S. E. & Parsons, S. B. Topographic controls of soil organic carbon on soil-mantled landscapes. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 6390. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42556-5 (2019).

Wiesmeier, M. et al. Amount, distribution and driving factors of soil organic carbon and nitrogen in cropland and grassland soils of southeast Germany (Bavaria). Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 176, 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2013.05.012 (2013).

Yimer, F., Ledin, S. & Abdelkadir, A. Soil organic carbon and total nitrogen stocks as affected by topographic aspect and vegetation in the Bale Mountains, Ethiopia. Geoderma 135, 335–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2006.01.005 (2006).

Bangroo, S. A., Najar, G. R. & Rasool, A. Effect of altitude and aspect on soil organic carbon and nitrogen stocks in the Himalayan Mawer Forest Range. Catena 158, 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2017.06.017 (2017).

Babaeian, E., Homaee, M., Carsten Montzka, C., Vereecken, H. & Ali Norouzi, A. A. Towards retrieving soil hydraulic properties by hyperspectral remote sensing. Vadose Zone J. https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2014.07.0080 (2015).

Martin, R. C., He, Y & Kaewniyom, K. Usability of Similar Bands for Soil Organic Matter Prediction. In Remote Sensing and Soil Monitoring Proceedings (University of Guelph, Canada, 2000).

Stenberg, B. Effects of soil sample pretreatments and standardised rewetting as interacted with sand classes on Vis-NIR predictions of clay and soil organic carbon. Geoderma https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2010.04.008 (2010).

Udelhoven, T., Emmerling, C. & Jarmer, T. Quantitative analysis of soil chemical properties with diffuse reflectance spectrometry and partial least-square regression: A feasibility study. Plant Soil 251, 319–329 (2003).

Clark, R. N., King, T. V. V., Klejwa, M., Swayze, G. A. & Vergo, N. High spectral resolution reflectance spectroscopy of minerals. J. Geophys. Res. 95, 12653–12680 (1990).

Islam, K., Singh, B. & McBratney, A. Simultaneous estimation of several soil properties by ultra-violet, visible, and near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy. Aust. J. Soil Res. 41, 1101–1114 (2003).

Tahmasbian, I. et al. Laboratory-based hyperspectral image analysis for predicting soil carbon, nitrogen and their isotope compositions. Geoderma 330, 254–263 (2018).

Xiaojun, N., Jianhui, Z. & Zhengan, S. Dynamics of soil organic carbon and microbial biomass carbon in relation to water erosion and tillage erosion. PLoS One 8(5), e64059. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064059 (2013).

Wu, L., Li, L. & Yao, Y. Spatial distribution of soil organic carbon and its influencing factors at different soil depths in a semiarid region of China. Environ. Earth Sci. 76, 654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-017-6982-1 (2017).

Bowers, S. A. & Hanks, R. J. Reflection of radiant energy from soils. Soil Sci. 100, 130–138 (1965).

Junting, Y. et al. High spatial resolution topsoil organic matter content mapping across desertified land in Northern China. Front. Environ. Sci. 9, 668912. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2021.668912 (2021).

Su, F. et al. Estimation of the cavity volume in the gasification zone for underground coal gasification under different oxygen flow conditions. Energy 285, 129309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.129309 (2023).

Yang, M., Xu, D., Chen, S., Li, H. & Shi, Z. Evaluation of machine learning approaches to predict soil organic matter and pH using vis-NIR spectra. Sensors 19(263), 1–14 (2019).

Ding, J., Yang, A., Wang, J., Sagan, V. & Yu, D. Machine-learning-based quantitative estimation of soil organic carbon content by VIS/NIR spectroscopy. PeerJ 6, e5714. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.5714 (2018).

Jia, J. et al. Comparing microbial carbon sequestration and priming in the subsoil versus topsoil of a Qinghai-Tibetan alpine grassland. Soil Biol. Biochem. 104, 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.10.018 (2017).

Viscarra-Rossel, R. A. & Behrens, T. Using data mining to model and interpret soil diffuse reflectance spectra. Geoderma 158, 46–54 (2010).

Kim, M.-J., Lee, J.-E., Back, I., Lim, K. J. & Mo, C. Estimation of total nitrogen content in topsoil based on machine and deep learning using hyperspectral imaging. Agriculture 2023, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13101975 (1975).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, T., Li, Y. & Wang, M. Prediction of soil organic carbon and total nitrogen affected by mine using Vis–NIR spectroscopy coupled with machine learning algorithms in calcareous soils. Sci Rep 14, 28014 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73761-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73761-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Soil total nitrogen prediction based on multi-temporal synthetic Sentinel-2 images under different land use types

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Evaluating the impact of soil moisture variation on the performance of visible and near-infrared (Vis–NIR) spectroscopy for predicting soil organic carbon content

Environmental Monitoring and Assessment (2025)