Abstract

Fungi in the genus Trichoderma are widespread in the environment, mainly in soils. They are used in agriculture because of their mycoparasitic potential; Trichoderma have the ability to increase plant health and provide protection against phytopathogens, making them desirable plant symbionts. We isolated, identified, and characterized Trichoderma from different regions of Saudi Arabia and evaluated the ability of Trichoderma to promote plant growth. Morphological and molecular characterization, along with phylogenetic studies, were utilized to differentiate between Trichoderma species isolated from soil samples in the Abha and Riyadh regions, Saudi Arabia. Then, plant growth-promoting traits of the isolated Trichoderma species were assessed. Eight Trichoderma isolates were characterized via morphological and molecular analysis; six (Trichoderma koningiopsis, Trichoderma lixii, Trichoderma koningii, Trichoderma harzianum, Trichoderma brevicompactum, and Trichoderma velutinum) were from Abha and two (T. lixii and T. harzianum) were from Riyadh. The isolated Trichoderma strains belonged to three different clades (Clade 1: Harzianum, Clade 2: Brevicompactum, and Clade 3: Viride). The Trichoderma isolates varied in plant growth-promoting traits. Seeds treated with most isolates exhibited a high percentage of germination, except seeds treated with the T3-T. koningii isolate. 100% germination was reported for seeds treated with the T4-T. harzianum and T6-T. brevicompactum isolates, while seeds treated with the T1-T. koniniopsis and T5-T. lixii isolates showed 91.1% and 90.9% germination, respectively. Seeds treated with the T8-T. velutinum, T2-T. lixii, and T7-T. harzianum isolates had germination rates of 84.1%, 82.2%, and 72.7%, respectively. The Trichoderma isolate T5-T. lixii stimulated tomato plant growth the most, followed by T7-T. harzianum, T8-T. velutinum, T4-T. harzianum, T1-T. koniniopsis, T2-T. lixii, and T6-T. brevicompactum; the least effective was T3-T. koningii. A maximum fresh weight of 669.33 mg was observed for the T5-T. lixii-treated plants. The Abha region had a higher diversity of Trichoderma species than the Riyadh region, and most isolated Trichoderma spp. promoted tomato growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The agricultural systems of Saudi Arabia have significantly improved during the last 10 years. Despite the common perception that Saudi Arabia is a desert, there are several areas where cultivation is possible. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is moving forward with plans (Vision 2030) to develop the agricultural sector because of its direct impact on food security. By doing so, the Kingdom attaches importance to issues of food and water security, agricultural development, and environmental sustainability. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (2009), the global population will reach 9.7 billion by 2050, and difficulties in meeting human food needs are expected due to the effects of climate change, a shrinking agricultural land area, and the degradation of the environment and natural resources, including the loss of numerous biodiversity components that are crucial to achieving sustainable agricultural production1. Research on fungal biodiversity within the genus Trichoderma and characterization of plant growth-promoting fungi is lacking in this region. Salinity and temperature are important factors in the agriculture of Saudi Arabia and plant growth-promoting fungi such as Trichoderma spp., which can tolerate high temperatures and salinities, are advantageous to agricultural production in this region. Considering the potential for Trichoderma species to increase plant growth and control phytopathogenic fungi, the present characterization of Trichoderma biodiversity was undertaken.

Trichoderma is a globally dispersed, ubiquitous genus in the family Hypocreaceae, and Trichoderma fungi may be found in various soil types and root ecosystems, particularly those rich in organic materials. Trichoderma fungi reproduce asexually by producing conidia and chlamydospores and by producing ascospores in their natural habitats. Some of the most beneficial effects of Trichoderma spp. on plants include the control of minor infections, the delivery of dissolved nutrients, increased nutrient intake, increased glucose metabolism and photosynthesis, phytohormone production, bioremediation of heavy metals and environmental contaminants, and use in xenobiotic bioremediation1,2,3 Trichoderma spp. can promote host plant resistance to a variety of biotic and abiotic stresses; they improve plant resistance to environmental challenges, including salt and drought, by stimulating plant growth, reprogramming gene expression in roots and shoots, maintaining nutritional uptake, and activating protective mechanisms to prevent oxidative damage4,5,6.

Applying Trichoderma spp. to seeds, seedlings, and pathogen-free soils has been shown to stimulate plant growth6. Symbioses occur between crops and soil microorganisms, such as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) and plant growth-promoting fungi (PGPF), which are both natural biostimulants. Trichoderma spp. that are PGPF have been used commercially to suppress phytopathogens such as Fusarium oxysporum, Rhizoctonia solani, Armillaria mellea, and Chondrostereum purpureum7. However, the antagonistic capability and biostimulant action of Trichoderma vary greatly, resulting in strains with predominant biostimulant action and others with predominant agonistic action8. As a result, some Trichoderma strains are better suited for biological control as biopesticides, while others are better suited for boosting crop growth and nutrient uptake as biostimulants9 Trichoderma species are effective mycoparasites that produce numerous secondary compounds, many of which have clinical significance9. Additionally, they have the ability to detect, penetrate, and destroy other fungi and certain nematodes, which contributes to their commercial success as biopesticides (more than 60% of all registered biopesticides contain Trichoderma).

Trichoderma species are distinguished by their rapid growth, ability to assimilate a wide range of substrates, and ability to produce a variety of antimicrobial agents. Trichoderma species synthesize siderophores as secondary metabolites with antibacterial properties that inhibit the growth of soil pathogens by scavenging iron and inactivating iron-dependent enzymes; thus, the fungi reduce plant disease and enhance plant growth10,11. Several Trichoderma species also have the ability to synthesize phytohormones and phytoregulators, including indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), which is important for plant growth and development12,13. Moreover, Trichoderma increase the bioavailability of phosphorus by breaking down insoluble phosphate in the soil via phytases, which facilitate and enhance the uptake of nutrients by plants. Previous studies have documented the strain-dependent growth-promoting effect of Trichoderma spp. on various plants, as well as the ability of different Trichoderma spp. to provide protection against plant diseases14,15. Attempts to understand the diversity and geographical distribution of Trichoderma/Hypocrea have resulted in global observations of the genus16, but unfortunately, there have been few studies of Trichoderma in Saudi Arabia7,17,18,19,20,21. The goal of this study was to isolate and characterize Trichoderma strains from different regions of Saudi Arabia and to evaluate their growth-promoting effects on plants.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and Trichoderma isolation

Soil samples were collected at six sites each in the Abha and Riyadh regions, Saudi Arabia. Seventy-two soil samples were collected from all six sites in each region, Riyadh and Abha. Nineteen Trichoderma strains were obtained from these soil samples. The soil dilution plate method was used for the isolation of fungi7,22. The morphological and colony characteristics of Trichoderma isolates were studied in potato dextrose agar (PDA) (HIMEDIA, India), medium and Trichoderma selective medium (TSM), following previous studies23,24. The macro characteristics (colony radius, pigments, green conidia, odor, and colony appearance) and microcharacteristics (phialide, conidium, and presence of chlamydospores) were observed.

Determination of physical and chemical soil properties

A pH meter was employed to measure the soil pH. For pH measurement, a soil suspension with a ratio of 1:2.5 (soil to water) was prepared and shaken for an hour25. Additionally, an electric conductivity meter assessed the electrical conductivity (EC) in the soil’s saturated paste extract. Meanwhile, soil moisture content (MC) was determined by oven drying at 103 °C for 12 h. The following equation calculates the percent moisture content in soil:

\({\text{MC}}\; \left( \% \right)=\left( {{\text{Wf}} - {\text{Wd}}/{\text{Wd}}} \right) \times 100\)

where:

-

MC (%) represents the moisture content in percentage.

-

(Wf) is the weight of fresh soil.

-

(Wd) is the weight of soil after drying in the oven.

To estimate organic matter (OM), the loss of ignition method was used26. The following equation calculates the percent organic matter in soil.

\({\text{OM}}\; \left( \% \right) = \left( {{\text{W}}2 - {\text{W}}3} \right)/\left( {{\text{W}}2 - {\text{W}}1} \right) \times 100\)

where OM (%) is percent organic matter in soil, W1 = Weight of the crucible, W2 = Weight of the crucible + oven dry sample, W3 = Weight of the crucible + oven dry sample after ignition.

To determine whether the Trichoderma strains selected for the studies were nonpathogenic, a plant pathogenicity test was conducted. Twenty healthy two-week-old tomato plants were inoculated with a suspension of Trichoderma strain (1 × 107 CFU/ml), and the roots were inoculated via the root-dip method. Inoculated plants were transplanted singly into steam-sterilized peat moss soil and sand mixed at a 5:1 ratio. Seedlings inoculated with sterilized water (1 ml per plant) served as controls. After one week, the plants were observed for any visible symptoms. The pathogenicity test was conducted twice.

Molecular identification of and phylogenetic analysis of isolated Trichoderma species

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and molecular identification of species of Trichoderma were performed27.

Phylogenetic analysis

For phylogenetic characterization of the isolated Trichoderma strains, the relevant downloaded sequences (Table 1) were aligned using Clustal W-pairwise sequence alignment of the EMBL nucleotide sequence database. The sequence alignments were trimmed and verified by the MUSCLE (UPGMA) algorithm using MEGA11 software, Auckland, New Zealand A phylogenetic tree was reconstructed, and the evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbor‒joining method. The robustness of the internal branches was assessed with 500 bootstrap replications. Evolutionary distances were computed using the maximum composite likelihood method and were calculated in units of the number of base substitutions per site.

Biochemical characterization of plant growth-promoting Trichoderma spp.

The isolated Trichoderma strains were assessed for phosphate solubilization and IAA, ammonia, and siderophore production.

Phosphate solubilization activity

The ability of 8 Trichoderma isolates to solubilize and mineralize phosphate (P) in vitro was evaluated, and qualitative screening of phosphate solubilization was performed on Pikovskaya agar medium (HIMEDIA, India)28.

Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production

For the quantitative estimation of IAA, DF salts in minimal media supplemented with L-tryptophan at a concentration of 1.02 g/l were prepared (HIMEDIA, INDIA)29,30.

Ammonia production

Freshly grown Trichoderma isolates were cultured in peptone water (HIMEDIA, India) broth in test tubes at 28 °C for 2 days31.

Siderophore production

Modified chrome azurol S (CAS) agar (HIMEDIA, India) with King’s media (Kings Media, Kochi, Kerala) (pH 6.8) was used11.

In vivo evaluation of the effect of Trichoderma isolates on tomato plant growth

The plant growth-promoting activity of the Trichoderma isolates was assessed by analyzing the seed germination and seedling growth of tomato plants31.

Effect of Trichoderma isolates on seed germination

Tomato seeds (Roma VF) were purchased from a local market (Salam Street) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines/regulations/legislation.

Fifty tomato seeds of uniform size were surface sterilized with 0.5% NaClO (Xilong Scientific Co., Ltd., China), for 5 min and washed five times with sterile water. Ten seeds were transferred to Petri plates covered with a layer of cotton and filter paper. A spore suspension of the Trichoderma isolates (105 spores/ml) was poured over the seeds (100 µl/seed), and the plates were cultured for 7 d at 28 °C under 12 h/12 h light/dark conditions. Seeds treated with an equivalent volume of sterile water were used as controls. At the end of two weeks, the germination rate was calculated using the following equation:

\({\text{Percent seed germination }}\left( \% \right)\; \left( {{\text{Gs}}} \right)\,=\,{\text{Ts}} \times 100\)

where Gs = the number of seeds germinated, and Ts = the total number of seeds31.

Effect of Trichoderma isolates on tomato plant growth

Tomato seeds were surface sterilized, treated with Trichoderma, and sown in pots containing 5 g of sterile soil. The pots were watered as required with sterile water. After 2 weeks, the seedlings were treated (0.5 ml) with Trichoderma strains (105 spores/ml), allowed to grow for two weeks, treated again with Trichoderma strains (105 spores/ml), and grown for an additional 2 weeks. Seedlings were watered with sterile water as needed. Six weeks after germination, the experiment was terminated, and the plants were uprooted. The plants were removed from the soil, and the roots were washed carefully under running water. The plant shoot height, root length, and wet weight were measured. The plants were then dried at 105 °C for 30 min and subsequently at 50 °C for 24 h, and plant dry weight was recorded32,33.

Results

After soil samples were collected from 6 locations in the Abha and Riyadh regions, PDA medium and TSM were used to isolate Trichoderma species. Twenty Trichoderma strains were isolated from soil samples collected from the Abha region, and 12 Trichoderma strains were isolated from soil samples collected from the Riyadh region. Subsequently, the isolates were purified and identified microscopically. The isolated Trichoderma strains were classified into six groups based on colony and morphological characteristics. A total of 16 isolates were selected for pathogenicity testing. Eight out of 34 isolates were selected for pathogenicity testing on tomato plants. From the PDA plates, a total of 8 Trichoderma strains were selected for further investigation. Soil from the Abha region had a higher diversity of Trichoderma species than soil from the Riyadh region. Among these 8 Trichoderma strains, six species (T. koningiopsis, T. lixii, T. koningii, T. harzianum, T. brevicompactum, and T. velutinum) were isolated from Abha, and two species (T. lixii and T. harzianum) were isolated from Riyadh (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8). The isolated Trichoderma species (Figs. 1 T1, 2 T2, 3 T3, 4 T4 and 5 T5, 6 T6, 7 T7 and 8 T8) were cultured at 28 °C for 7 days. Panels T1–T4 show (A) the anterior side of the PDA plate, (B) the superior side of the PDA plate, (C) chlamydospores, and (D, E, F, G, H, and I) conidiophores and phialides; (D) shows conidiation pustules on Pikorskaya agar after 4 days; (E, F) show conidia. The populations of fungi in both regions presented maximum CFU/g values of 45.3 × 102 and 83 × 102 for the Abha region and 14 × 102 and 47 × 102 for the Riyadh region. Moreover, soil from the Abha region exhibited greater fungal diversity than soil from the Riyadh region.

The selected Trichoderma species (T-4) were cultured at 28 °C for 7 days. P (A) the anterior side of the PDA plate, (B) the superior side of the PDA plate, (C) chlamydospores, and (D,E) conidiophores and phialides; (D) shows conidiation pustules on Pikorskaya agar after 4 days; (E–H,I) show conidia.

Molecular identification and phylogenetic analysis of the isolated Trichoderma species

The identities of the Trichoderma isolates were confirmed by molecular analysis. The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of fungal 18s rDNA was amplified using primers ITS4 and ITS. Searches using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) (NCBI GenBank) were performed, and the results are presented in Table 2.

Phylogenetic analysis

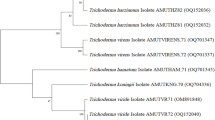

A phylogenetic tree was constructed by analyzing nineteen sequences, including the sequences of the eight isolated Trichoderma species, 10 Trichoderma species from GenBank and a Fusarium oxysporum (MT151384) sequence as an outgroup (Fig. 9). MEGA11 was used for evolutionary analysis. The evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbor-joining method, and the evolutionary distances were computed using the maximum composite likelihood method. The results revealed a total of 464 positions in the final dataset. We observed that T. harzianum, T. velutinum, and T. lixii were closely related and belonged to the Harzianum clade (Clade 1), while T. brevicompactum belonged to the Brevicompactum clade (Clade 2), and T. koningiopsis and T. koningii belonged to the Viride clade (Clade 3).

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree based on ITS 4 and ITS 5 region sequences of eight isolated Trichoderma species, 10 Trichoderma species from GenBank, and F. oxysporum as an outgroup. The evolutionary distances were computed using the maximum composite likelihood method. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (500 replicates) is shown next to the branches. Clade 1: Harzianum, Clade 2: Brevicompactum, and Clade 3: Viride.

Characterization of plant growth-promoting Trichoderma spp.

Biochemical analyses were performed to characterize the plant growth-promoting activity of Trichoderma. The isolates were assessed for phosphate solubilization, and IAA, ammonia, and siderophore production. The results are presented in Table 3.

Biochemical tests were performed to evaluate the promotion factors detected in Trichoderma species. The phosphate solubilization efficacy of the Trichoderma isolates was evaluated on Pikovaskaya agar by acidification, and all eight isolates utilized trisodium phosphate in Pikovaskaya agar and showed positive results (Fig. 10a,b). The ability to produce ammonia differed by isolate (Table 3). The highest production was exhibited by T4 (T. harzianum), T5 (T. lixii) and T7 (T. harzianum), and the other isolates, T1 (T. koniniopsis), T2 (T. lixii), T3 (T. koningii), T6 (T. brevicompactum), and T8 (T. velutinum), displayed moderate production (Table 3; Fig. 10c). Qualitative and quantitative analyses were conducted to determine IAA production by the eight Trichoderma isolates in culture media supplemented with tryptophan as a precursor. Interpolation of spectrophotometer readings using standard curves was used to quantify the amount of IAA produced by different isolates of Trichoderma. The production of IAA differed by isolate (Table 3). A high amount of IAA was produced by T. brevicompactum (51.24 ± 0.18 µg/ml) and T. lixii (50.82 ± 0.65 µg/ml), whereas T. koniniopsis (0.15 ± 0.052 µg/ml) was the lowest producer in media supplemented with tryptophan (Fig. 10d). Siderophore production also differed by isolate (Table 3). The ability to produce siderophores was demonstrated by the formation of orange halos around the colonies on the blue modified CAS agar plate (Fig. 10e,f). The T3 and T4 isolates (T. koningii and T. harzianum, respectively) showed maximum zone formation, which was observed after 5 d. Approximately 25% of the isolates showed high siderophore production, and the remaining isolates were moderate producers. No zone formation was observed for isolates T5 (T. lixii) and T8 (T. velutinum).

Biochemical assays. Panel (a) shows the negative control (media without Trichoderma). Panel (b) shows Trichoderma species T1 was positive for phosphate solubilization. Panel (c) shows ammonia production of Trichoderma species T6. Panel (d) shows IAA production by Trichoderma species T6. Panel (e) shows the negative control for siderophore production in media without Trichoderma. Panel (f) shows the T3 and T4 species in the left and right images, respectively. A wide zone appears, which means that those species produce siderophores.

In vivo evaluation of the effect of plant growth promoting Trichoderma on tomato plant growth

Effect of Trichoderma isolates on seed germination

Tomato seeds treated with Trichoderma isolates were observed for one week for seed germination. Compared with the control, priming with Trichoderma isolates significantly increased seed germination (P ≤ 0.05), except for the T3 isolate. Seed germination was 100% in seeds treated with the T4 and T6 isolates, while seeds treated with the T1 and T5 isolates showed 91.1% and 90.9% seed germination, respectively. The seed germination rates for the T8, T2, and T7 isolates were 84.1%, 82.2%, and 72.7%, respectively. Seed germination after treatment with the T3 isolate was statistically equivalent to the control (P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 11).

The effects of Trichoderma isolates on seed germination. The data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) according to a Tukey HSD test. C: Control, T1: T. koniniopsis, T2: T. lixii, T3: T. koningii, T4: T. harzianum, T5: T. lixii, T6: T. brevicompactum, T7: T. harzianum, and T8: T. velutinum.

Effects of Trichoderma isolates on tomato plant growth

Overall, Trichoderma isolates significantly (P ≤ 0.05) increased tomato plant growth compared to that of untreated control plants (Fig. 12). Among the plants that received Trichoderma isolates, the greatest increase in shoot height was observed for the plants treated with T5-T. lixii (16.16 cm) followed by those treated with T7-T. harzianum (13.33 cm), T1-T. koniniopsis (11.33 cm), T2-T. lixii (10.83 cm), T4-T. harzianum (10.83 cm), T8-T. velutinum (10.16 cm), T6-T. brevicompactum (7.00 cm), and T3-T. koningii (5.70 cm). Post hoc analysis of shoot height indicated that most of the treatments were significantly different (P ≤ 0.05) from each other, except for T3-T. koningii, which was equivalent to control plants. Conversely, the greatest increase in root length was recorded in the plants treated with T7-T. harzianum (7.23 cm), followed by those treated with T5-T. lixii (6.83 cm), T8-T. velutinum (5.16 cm), T4-T. harzianum (4.53 cm), T2-T. lixii (3.30 cm), T3-T. koningii (3.20 cm), T6-T. brevicompactum (2.76 cm) and T1-T. koniniopsis (2.40 cm). Post hoc analysis of plant root length revealed that there was no significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) between T7-T. harzianum and T5-T. lixii or among the T2-T. lixii, T3-T. koningii, and T6-T. brevicompactum treatments. The greatest plant fresh weight was observed for the plants treated with T5-T. lixii (669.33 mg), followed by those treated with T7-T. harzianum (359.33 mg), T8-T. velutinum (299.67 mg), T3-T. koningii (284.33 mg), T4-T. harzianum (197.33 mg), T1-T. koniniopsis (193.0 mg), T2-T. lixii (146.33 mg), and T6-T. brevicompactum (73.00 mg). The maximum plant dry weight was observed for the plants treated with T5-T. lixii (28.7 mg), T7-T. harzianum (22.67 mg), T8-T. velutinum (13.4 mg), T1-T. koniniopsis (11.4 mg), T4-T. harzianum (10.37 mg), T2-T. lixii (9.67 mg), T3-T. koningii (7.7 mg), and T6-T. brevicompactum (5.7 mg). Analysis of plant fresh and dry weight revealed a significant (P ≤ 0.05) difference between the control plants and the plants in the other treatment groups. However, there was no significant difference in the fresh weight of plants in the control and T6-T. brevicompactum groups or among the T1-T. koniniopsis, T2-T. lixii, and T4-T. harzianum groups. A significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) in plant dry weight was detected among all treatments (Table 4).

Tomato plant growth after the first treatment and 2 weeks (W2), 3 weeks (W3), 5 weeks (W5), and 7 weeks (W7) after sowing. Control, C. Treatments included (1) T. koniniopsis, (2) T. lixii, (3) T. koningii, (4) T. harzianum, (5) T. lixii, (6) T. brevicompactum, (7) T. harzianum, and (8) T. velutinum.

Principal component analysis (PCA) for plant growth parameters and seed germination was performed to understand the effect of Trichoderma isolates on plant growth. The PCA biplot in Fig. 13 shows that shoot height, root length, plant fresh weight, and plant dry weight were highly correlated. Seed germination was moderately correlated with the other plant growth parameters. Trichoderma isolate T5-T. lixii had the greatest positive impact on plant growth; T7-T. harzianum and T8-T. velutinum also fell into the same quadrant, demonstrating a positive effect on plant growth. T4-T. harzianum also increased plant growth, as it fell into the second quadrant. T1-T. koniniopsis, T2-T. lixii, and T6-T. brevicompactum moderately increased plant growth, whereas plants that received T3-T. koningii were similar in growth to control plants.

The left images show root growth of tomato plants treated with Trichoderma isolates. Control, C. The right image shows the PCA biplot for tomato plant growth parameters. Treatments included the control (C), T. koniniopsis (1), T. lixii (2), T. koningii (3), T. harzianum (4), T. lixii (5), T. brevicompactum (6), T. harzianum (7), and T. velutinum (8). Germ (%): seed germination, Sh: shoot height, RL: root length, FW: plant fresh weight, and DW: plant dry weight.

Discussion

Fungi from the genus Trichoderma have been widely used in agriculture because of their mycoparasitic potential and their ability to improve plant health and protect against phytopathogens, making them desirable symbionts. The goal of the current study was the isolation, molecular identification, and characterization of Trichoderma from Saudi Arabia34 and the evaluation of their ability to promote plant growth.

Soil properties of the samples collected from Abha and Riyadh were also determined. In the Riyadh region, soil pH varied from mild to extremely alkaline, while soil in the Abha region had a neutral pH. The EC values also varied widely in both regions. Previous studies have reported different pH and EC values in the Riyadh region. Masoud & Aal reported an average pH of 7.64; however, their sample sites were different from those in the present study34. Al Barakah et al.35 reported mean pH and EC values of 7.7 and 1.03 dS/m, respectively. Siham36 reported a pH range of 7.58–7.76 and EC values of 22.5–32.0 from an industrial city in Riyadh. Irrigation water and dissolving soil minerals are some sources of salts in soil. Moreover, the Riyadh region is rich in weathered limestone, and the climate is exceedingly arid; therefore, evapotranspiration exceeds precipitation. These factors may contribute to higher pH and alkalinity34,37. The organic matter content of soil in the Abha region was greater than that in the Riyadh region. Since most soil in the Abha region was from a vegetation area, organic matter can be attributed to the decomposition of dead plant materials. As expected, the moisture content varied according to the sample collection site. The soil samples collected near a water body had a higher moisture content than the other samples. The Riyadh and Abha regions both had large populations of soil fungi. Recently, fungal populations were shown to range from 4.19 to 4.67 CFU/g in the Riyadh region, and the presence of Trichoderma was also observed17,21,38,39,40.

The soil fungi of Saudi Arabia have been investigated previously, and although Trichoderma was not detected in desert soil samples41, other studies reported Trichoderma in soils from other sources42,43,44. In the present study, we isolated eight Trichoderma species (T. koningiopsis, T. lixii, T. koningii, T. harzianum, T. brevicompactum, T. velutinum, T. lixii, and T. harzianum) from the Abha and Riyadh regions. Similarly, Hussein & Yousef isolated two species of Trichoderma (T. harzianum and Trichoderma sp.) from petroleum-contaminated soil43. Additionally, Abd-Elsalam identified two Trichoderma complex species (T. harzianum/H. lixii and T. longibrachiatum/H. orientalis) from soil collected from Rawdet Khuraim in Saudi Arabia using morphological criteria and DNA sequence analysis18.

Molecular characterization based on multiple gene sequencing enables the accurate identification of Trichoderma species. Previous reports of Trichoderma isolation and characterization in Saudi Arabia depended on morphological methods, which may not distinguish closely related species. Globally, in 1998, Kindermann and others attempted to study the phylogeny of the whole Trichoderma genus based on sequencing of the ITS region, and they demonstrated that this approach was a powerful method of identifying Trichoderma species. Other researchers have since reported the importance of the ITS sequence in Trichoderma species identification44,45,46,47,48. However, our study aimed to provide an extra reliable method for the identification of Trichoderma species in Saudi Arabia We targeted the ITS region of rDNA, which is one of the most frequently targeted regions for the molecular characterization of Trichoderma species. We identified T. koniniopsis, T. velutinum, T. brevicompactum, two isolates of T. harzianum, two isolates of T. lixii, and T. koningii. This is the first time that such diverse Trichoderma species have been reported in Saudi Arabia.

Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the Trichoderma isolates belonged to three different clades. T. harzianum, T. velutinum and T. lixii were closely related and belonged to the Harzianum clade. This finding is consistent with that of Gherbawy38, who identified 91 Trichoderma isolates based on ITS regions from the soil of Taif City, Saudi Arabia. A total of 78 isolates from the population were identified as Trichoderma harzianum (Tel. Hypocrea lixii). Additionally, Chaverri and others24 reported that T. harzianum showed high similarity with T. lixii. Other molecular sequence data has demonstrated that T. harzianum is a genetically variable complex composed of one morphological species and several phylogenetic species49.

Trichoderma species have beneficial effects on plants, including enhancing plant growth, root structure, seed germination, viability, photosynthetic efficiency, flowering, and yield quality, thereby promoting overall plant health50. In the present study, eight species of Trichoderma were investigated for plant growth-promoting traits, including phosphate solubilization and IAA, ammonia, and siderophore production. The Trichoderma isolates varied in terms of their plant growth-promoting traits. All the isolates were able to mobilize phosphate, while T. harzianum and T. lixii produced the greatest amount of ammonia. T. koningii and T. harzianum were superior in siderophore production, and T. brevicompactum and T. lixii produced the most IAA. Additionally, these eight isolates of Trichoderma were evaluated for their ability to stimulate tomato seed germination and plant growth in the early stages of seedling development. The results showed that all the Trichoderma isolates significantly increased seed germination and plant growth, especially the T5-T. lixii, T7-T. harzianum, and T8-T. velutinum isolates, which were highly effective at stimulating plant growth by increasing shoot and root length and the fresh and dry weights of shoots and roots. Our results are consistent with those obtained by Bader15, who noted that a set of Trichoderma strains can produce IAA, solubilize phosphate, and promote tomato plant growth by increasing shoot length and the fresh and dry weights of shoots and roots.

Conclusion

The goal of the present study was to identify examples of the plant growth-promoting fungus Trichoderma in two regions of Saudi Arabia, Abha and Riyadh, by utilizing morphological and molecular tests. The soil properties of Abha and Riyadh differ significantly, as does the fungal population in these areas. Six diverse Trichoderma species were detected in Abha soil, while only two different species were isolated from Riyadh soil. Molecular identification and phylogenetic analysis confirmed the following six species: T. koniniopsis, T. velutinum, T. brevicompactum, T. harzianum, T. lixii, and T. koningii. Phylogenetic analysis based on ITS sequences grouped the strains into three clades. The Trichoderma isolates varied in phosphate solubilization and IAA, ammonia, and siderophore production, which are plant growth-promoting traits. In vivo experiments on tomato plants showed that all Trichoderma isolates except T3-T. koningii increased seed germination. The Trichoderma isolate T5-T. lixii had the greatest effect on tomato plant growth, followed by T7-T. harzianum, T8-T. velutinum, T4-T. harzianum, T1-T. koniniopsis, T2-T. lixii, and T6-T. brevicompactum; the least effective was T3-T. koningii. To our knowledge, this is the first characterization of plant growth-promoting Trichoderma and identification of T. brevicompactum from Saudi Arabia.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Cabral-Miramontes, J. P., Olmedo-Monfil, V., Lara-Banda, M., Zúñiga-Romo, E. R. & Aréchiga-Carvajal, E. T. Promotion of plant growth in arid zones by selected Trichoderma spp. strains with adaptation plasticity to alkaline pH. Biology (Basel) 11, 1206 (2022).

Natsiopoulos, D., Tziolias, A., Lagogiannis, I., Mantzoukas, S. & Eliopoulos, P. A. Growth-promoting and protective effect of Trichoderma atrobrunneum and T. simmonsii on tomato against soil-borne fungal pathogens. Crops 2, 202–217 (2022).

Tyśkiewicz, R., Nowak, A., Ozimek, E. & Jaroszuk-ściseł, J. Trichoderma: The current status of its application in agriculture for the biocontrol of fungal phytopathogens and stimulation of plant growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 2329 (2022).

Mona, S. A. et al. Increased resistance of drought by Trichoderma harzianum fungal treatment correlates with increased secondary metabolites and proline content. J. Integr. Agric. 16, 1751–1757 (2017).

Stewart, A. & Hill, R. Applications of Trichoderma in plant growth promotion. In Biotechnology and Biology of Trichoderma, 415–428 (Elsevier, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-59576-8.00031-X.

Adnan, M. et al. Plant defense against fungal pathogens by antagonistic fungi with Trichoderma in focus. In Microbial Pathogenesis, vol. 129, 7–18 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2019.01.042.

El-Komy, M. H., Saleh, A. A., Eranthodi, A. & Molan, Y. Y. Characterization of novel Trichoderma asperellum isolates to select effective biocontrol agents against tomato fusarium wilt. Plant. Pathol. J. (Faisalabad) 31, 50–60 (2015).

Baiyee, B., Ito, S. & Sunpapao, A. Trichoderma asperellum T1 mediated antifungal activity and induced defense response against leaf spot fungi in lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 106, 96–101 (2019).

Mukherjee, P. K., Horwitz, B. A., Herrera-Estrella, A., Schmoll, M. & Kenerley, C. M. Trichoderma research in the genome era. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-082712-102353 (2013).

Harman, G. E., Howell, C. R., Viterbo, A., Chet, I. & Lorito, M. Trichoderma species—Opportunistic, avirulent plant symbionts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 43–56 (2004).

Ghosh, S. K., Banerjee, S. & Sengupta, C. Bioassay, characterization and estimation of siderophores from some important antagonistic fungi. J. Biopestic. 10, 105–112 (2017).

Ozimek, E. et al. Synthesis of indoleacetic acid, gibberellic acid and ACC-deaminase by Mortierella strains promote winter wheat seedlings growth under different conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 1–17 (2018).

Jaroszuk-ściseł, J. et al. Phytohormones (auxin, gibberellin) and ACC deaminase in vitro synthesized by the mycoparasitic Trichoderma DEMTKZ3A0 strain and changes in the level of auxin and plant resistance markers in wheat seedlings inoculated with this strain conidia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 1–35 (2019).

Alfiky, A. & Weisskopf, L. Deciphering Trichoderma–plant–pathogen interactions for better development of biocontrol applications. J. Fungi 7, 1–18 (2021).

Qi, W. & Lei, Z. Study of the siderophore-producing Trichoderma asperellum Q1 on cucumber growth promotion under salt stress. J. Basic. Microbiol. 53 (4), 355 (2013).

Sagrita. Studies on native strains of Trichoderma compatible with fertilizers and their bioefficacy against Chickpea wilt pathogen. Doctoral dissertation, Rvskvv, Gwalior (MP) (2017).

Molan. Detection of presumptive mycoparasites in soil placed on hostcolonized agar plates in Riyadh region, Saudi Arabia (2009).

Abd-Elsalam, K. A., Almohimeed, I., Moslem, M. A. & Bahkali, A. H. M13-microsatellite pcr and rdna sequence markers for identification of Trichoderma (Hypocreaceae) species in Saudi Arabian soil. Genet. Mol. Res. 9, 2016–2024 (2010).

Perveen, K. & Bokhari, N. A. Antagonistic activity of Trichoderma harzianum and Trichoderma viride isolated from soil of date palm field against Fusarium oxysporum. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 6, 3348–3353 (2012).

Gherbawy, Y. et al. Soil and soil properties. Mycol. Prog. 3, 211–218 (2004).

Mazrou, Y. S. A. et al. Comparative molecular genetic diversity between Trichoderma spp. Egypt and Saudi Arabia. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-020-00318-w (2020).

Elad, Y., Chet, I. & Henis, Y. Degradation of plant pathogenic fungi by Trichoderma harzianum. Can. J. Microbiol. 28 (7), 719 (1982).

Jaklitsch, W. M. & Voglmayr, H. iodiversity of Trichoderma (Hypocreaceae) in Southern Europe and Macaronesia. Stud. Mycol. 80, 1–87 (2015).

Chaverri, P., Castlebury, L. A., Samuels, G. J. & Geiser, D. M. Multilocus phylogenetic structure within the Trichoderma harzianum/Hypocrea lixii complex. Mol. Phylogenet Evol. 27, 302–313 (2003).

Rhoades, J. D. & Oster, J. D. Solute content. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 1 Physical and Mineralogical Methods, vol. 5, 985–1006 (1986).

Gessesse, T. A. & Khamzina, A. How reliable is the Walkley-Black method for analyzing carbon-poor, semi-arid soils in Ethiopia? J. Arid Environ. 153, 98–101 (2018).

Alwadai, A. S., Perveen, K. & Alwahaibi, M. The isolation and characterization of antagonist Trichoderma spp. from the soil of Abha, Saudi Arabia. Molecules 27 (2022).

Vazquez, P., Holguin, G., Puente, M. E., Lopez-Cortes, A. & Bashan, Y. Phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms associated with the rhizosphere of mangroves in a semiarid coastal lagoon. Biol. Fertil. Soils 30, 460–468 (2000).

Dworkin2, M. & Foster, J. W. Experiments with Some Microorganisms Which Utilize Ethane and Hydrogen’ (1958). http://jb.asm.org/

Gordon, S. A. & Weber, R. P. Colorimetric estimation of indoleacetic acid. Plant. Physiol. 192–195 (1951).

Ahmad, F., Ahmad, I. & Khan, M. S. Screening of free-living rhizospheric bacteria for their multiple plant growth promoting activities. Microbiol. Res. 163, 173–181 (2008).

Bokhari, N. A. & Perveen, K. Antagonistic action of Trichoderma harzianum and Trichoderma viride against Fusarium solani causing root rot of tomato. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 6, 7193–7197 (2013).

Kleifeld, O. & Chet, I. Trichoderma harzianum-interaction with plants and effect on growth response. Plant Soil 144, 267–272 (1992).

Masoud, A. A. & Aal, A. K. A. Three-dimensional geotechnical modeling of the soils in Riyadh city, KSA. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 78, 1–17 (2019).

Barakah, A. L., Alnohait, F. N., Ramzan, F. A. S., Radwan, S. & M. S. M. & Microbial diversity in the rhizosphere of some wild plants in Riyadh region, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 9, 3518–3534 (2020).

Siham, A. K. A. Effect of lead and copper on the growth of heavy metal resistance fungi isolated from second industrial city in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J. Appl. Sci. 7 (7), 1019 (2007).

Oumenskou, H. et al. Multivariate statistical analysis for spatial evaluation of physicochemical properties of agricultural soils from Beni-Amir irrigated perimeter, Tadla plain, Morocco. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 3, 83–94 (2019).

Gherbawy, Y. A., Hussein, N. A. & Al-Qurashi, A. A. Original research article molecular characterization of Trichoderma populations isolated from soil of Taif City, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 3, 1059–1071 (2014).

Elazab, N. T. Diversity and biological activities of endophytic fungi at Al-Qassim region. J. Mol. Biol. Res. 9, 160 (2019).

Al-Dhabaan, F. A. Mycoremediation of crude oil contaminated soil by specific fungi isolated from Dhahran in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 28, 73–77 (2021).

Abdel-Hafez, S. I. I. Survey of the mycoflora of desert soils in Saudi Arabia. Department of Biology, Center of Science and Mathematics. P. O. Box 1070, Taif, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Abstract. 8 (1982).

Youssef, A. Y., Karram El Din, A. A. & Ramadani, A. Isolation of keratinophilic fungi, including three species of dermatophytes from soils in Makkah and Taif E Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 5, 42–49 (1998).

Hussein, N. A. & Yousef, N. M. H. Microbial population of soil contamination with petroleum derivatives and molecular identification of Aspergillus niger (2011).

Druzhinina, I. & Kubicek, C. P. Species concepts and biodiversity in Trichoderma and Hypocrea: From aggregate species to species clusters. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. 6 B, 100–112 (2005).

Kubicek, C. P., Bissett, J., Druzhinina, I., Kullnig-Gradinger, C. & Szakacs, G. Genetic and metabolic diversity of Trichoderma: A case study on South-East Asian isolates. Fungal Genet. Biol. 38, 310–319 (2003).

Chakraborty, B. N., Chakraborty, U., Saha, A. & Dey, P. L. Molecular characterization of Trichoderma viride and Trichoderma harzianum isolated from soils of North Bengal based on rDNA markers and analysis of their PCR-RAPD profiles. Glob. J. Biotechnol. Biochem. 5(1), 55 (2010).

Savitha, M. J. & Sriram, S. Morphological and molecular identification of Trichoderma isolates with biocontrol potential against Phytophthora blight in red pepper. Pest Manag. Hortic. Ecosyst. 21, 194–202 (2015).

Kullnig-Gradinger, C. M., Szakacs, G. & Kubicek, C. P. Phylogeny and evolution of the genus Trichoderma: A multigene approach. Mycol. Res. 106 (7), 75 (2002).

s11557-006-0091-y.

Halifu, S., Deng, X., Song, X. & Song, R. Effects of two Trichoderma strains on plant growth, rhizosphere soil nutrients, and fungal community of Pinus sylvestris var. Mongolica annual seedlings. Forests. 10, 1–17 (2019).

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2024R173), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for their funding, which played a crucial role in the successful execution of this study and the attainment of our research goals.

Funding

Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP2024R173), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.A., K.P. and M.S.A.; Data curation, A.S.A. and M.S.A.; Investigation, M.F.A. and K.P.; Methodology, A.S.A.; N.A.A.; Supervision, R.E.; Writing—original draft, A.S.A. and R.E.; Writing—review and editing, M.S.A. and K.P. The authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Sample availability

Samples of the compounds are not available from the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alwadai, A.S., Al Wahibi, M.S., Alsayed, M.F. et al. Molecular characterization of plant growth-promoting Trichoderma from Saudi Arabia. Sci Rep 14, 23236 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73762-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73762-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Copper bioremediation by Trichoderma spp.

Biologia (2026)