Abstract

This study delves into the development and optimization of photocatalysts, namely ZnO NPs/Zeolite and TiO2 NPs/Zeolite, for the degradation of two beta-blocker drugs, including Atenolol (AT) and Metoprolol (ME). Structural and morphological analyses of the catalysts were conducted, and optimal conditions for drug degradation were determined using a Box-Behnken design. The results underscored the significant influence of pH, catalyst amount, drug concentration, and H2O2 concentration on the degradation process using ZnO NPs/Zeolite and TiO2 NPs/Zeolite as the catalysts. The optimal values of drug concentration, pH, catalyst amount, and H2O2 concentration, were determined to be 32 and 33 mg L−1, 4.2 and 4.6, 428 and 386 mg, and 2.6 and 2.5 mM utilizing ZnO NPs/Zeolite and TiO2 NPs/Zeolite as the catalyst, respectively. Following optimization, the kinetics of the photodegradation process were investigated, revealing promising rates and half-life times for both drugs. The pseudo-first-order rate constants for Atenolol and Metoprolol degradation were 0.064 ± 0.007 min−1 and 0.065 ± 0.004 min−1 with ZnO NPs/Zeolite and 0.071 ± 0.007 min−1 and 0.071 ± 0.006 min−1 with TiO2 NPs/Zeolite, respectively. Furthermore, ZnO NPs/Zeolite and TiO2 NPs/Zeolite demonstrated reusability up to 5 and 6 times, respectively, without significant activity loss. The comparative analysis highlighted the superior performance of TiO2 NPs/Zeolite over ZnO NPs/Zeolite, attributed to lower consumption, shorter degradation time, improved reusability, and compatibility with milder acidic conditions. Overall, the research showcases the potential of ZnO NPs/Zeolite and TiO2 NPs/Zeolite as an effective and sustainable solution for removing Metoprolol and Atenolol contaminants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Beta-blockers are pharmaceutical agents that interfere with the action of adrenaline and noradrenaline in the body, thereby playing a crucial role in managing hypertension, angina, arrhythmias, heart failure, and other cardiovascular disorders1. Among the widely prescribed beta-blockers, atenolol and metoprolol stand out for their efficacy and safety profiles2. The majority of atenolol and metoprolol, along with their metabolites, are primarily eliminated from the body via renal excretion in the urine3. However, a small portion of these drugs may also undergo elimination through fecal excretion and respiratory excretion4,5. It is worth noting that individual factors, such as age, gender, and health conditions, can influence the specific discharge pathways of these medications.

Despite their benefits in treating cardiovascular conditions, the use of atenolol and metoprolol can have potential environmental implications, particularly through their presence in water bodies6. These drugs can enter the environment through various pathways, including human excretion, improper disposal of unused medications, and discharge from wastewater treatment plants7,8. Studies have identified the presence of beta-blockers in surface water, groundwater, and even drinking water sources9. The incomplete removal of these compounds during wastewater treatment processes contributes to their persistence in the environment. While the levels of beta-blockers detected in environmental samples are generally low and not considered an immediate threat to human health, they can have adverse effects on aquatic organisms10. Research indicates that atenolol and metoprolol may disrupt the behavior, reproduction, and development of certain species when present in water sources11. Prolonged exposure to these beta-blockers can negatively impact fish, algae, and other aquatic organisms, although such effects typically occur at higher concentrations than those commonly found in the environment12,13. Therefore, removing these beta-blockers from the environment due to their impact on water systems is necessary.

Photodegradation, combined with the use of catalysts, presents a promising strategy for accelerating the removal of atenolol and metoprolol from water sources, thereby addressing the challenges associated with their presence in the environment14,15. The integration of catalysts into photodegradation processes can significantly enhance the degradation efficiency of target compounds, including beta-blockers16. Catalysts facilitate the activation of reactive species, promote electron transfer processes, and increase the degradation kinetics of pharmaceutical residues under light irradiation17. Catalytic materials, such as titanium dioxide (TiO2), zinc oxide (ZnO), and other semiconductor nanoparticles, can act as photocatalysts to initiate oxidation reactions when exposed to light18. These catalysts generate electron-hole pairs upon illumination, leading to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that contribute to the degradation of beta-blockers in water19,20. The incorporation of catalysts into photodegradation processes offers several advantages for the removal of beta-blockers: (i) Catalysts enhance the photodegradation kinetics, leading to faster and more efficient removal of atenolol and metoprolol from water sources compared to conventional photodegradation methods21. (ii) Catalysts can selectively promote the degradation of specific pollutants, such as beta-blockers, while minimizing the degradation of non-target compounds, thereby improving the selectivity of the degradation process22.

Zeolite is a porous material that has been widely used as a substrate for photocatalysts, including ZnO and TiO223. The incorporation of these catalysts onto a zeolite substrate can significantly enhance their photocatalytic activity by providing a higher surface area for the catalyst to interact with the target pollutants in the water24. The zeolite substrate acts as a support for the catalyst, providing a stable and uniform surface for the deposition of these nanoparticles25. This enables the nanoparticles to be evenly distributed over the substrate, maximizing their photocatalytic activity26. Additionally, the zeolite substrate can also provide a protective layer for the nanoparticles, preventing their agglomeration and improving their stability under irradiation27,28. Furthermore, the use of a zeolite substrate can also improve the selectivity of the photocatalytic process by enabling the separation of the catalyst and the target pollutant.

This research focuses on preparing ZnO NPs/Zeolite and TiO2 NPs/Zeolite photocatalysts for the degradation of AT and ME. The morphology and structure of both catalysts were characterized. A Box-Behnken design identifies the crucial impact of pH, catalyst amount, drug, and H2O2 concentration and their binary interactions on the degradation efficiency of these drugs using the catalysts. Besides, the kinetics of the degradation procedure and hilf-life time were evaluated using the first-order kinetic model. Besides, the reusability of the catalysts under the optimum conditions was investigated.

Experimental

Material

Atenolol and metoprolol were obtained from Samisaz Co (Mashhad, Iran). Other materials for preparing photocatalysts, including Zinc acetate dihydrate (≥ 98%), Zeolites (particle size < 45 μm), Sodium hydroxide(≥ 97%), Nitric acid (70%), Titanium (IV) butoxide (97%), and Ethanol were purchased from Sigma-Aldirch.

Instruments

Atenolol and metoprolol were quantified by employing an Agilent 1200 series instrument (USA) equipped with a photodiode array detector (1024 series). Analysis was performed using an Agilent Eclipse XDB-C18 column with a particle size of 5 mm (250 mm & 4.6 mm I.D.) at room temperature. The mobile phase consisted of phosphate buffer (0.01 M, pH 3.0), acetonitrile, and methanol in a ratio of 10%:10%:80% v/v. The flow rate was initially set at 1.0 mL min−1 for 4 min, then increased to 1.5 mL min−1. Atenolol and metoprolol were detected at 223 and 220 nm, respectively, using the photodiode array detector29.

The morphology of the photocatalysts was examined using various instruments, including a Fourier Transform Infrared spectrometer (FT-IR, Bruker, Germany), X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Philips PW 3710), Field Emission-Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM, Mira 3 Tescan; Czech Republic), and Brunauer-Emmett-Teller analysis (BET, BELSORP Mini II, Japan). A Metrohm 780 pH meter (Herisau, Switzerland) was used to adjust the pH of the solution.

Photocatalyst preparation

In this study, various catalysts, including ZnO nanoparticles (ZnO NPs), TiO2 nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs), ZnO NPs/Zeolite, and TiO2 NPs/Zeolite, were prepared and their efficiency in degrading atenolol and metoprolol was investigated and compared.

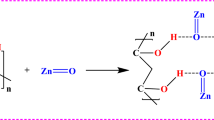

ZnO nanoparticles/zeolite

ZnO nanoparticles/Zeolite were prepared using a co-precipitation method30. Briefly, 0.674 g of Zn(CH3COO)2·2H2O and 5.0 g of Zeolite (with a ratio of Zeolite to ZnO of 95:5 w/w%) were dissolved in 100 mL of distilled water. The mixture was then refluxed at 80 °C for 5 h to exchange Zn ions with ions in the Zeolite. Sodium hydroxide (0.1 M) was added dropwise to the mixture until the pH reached 11. The resulting precipitate was separated, washed with distilled water, dried at 60 °C, and then calcined at 450 °C for 2 h30. To compare the catalyst activity, ZnO NPs were synthesized using a similar method without the addition of Zeolite and the reflux step. The synthesis procedure is presented in Scheme 1.

TiO2 NPs/zeolite

For the preparation of TiO2 NPs/Zeolite, a sol-gel method was employed31. Titanium (IV) butoxide (1.1 mL) was mixed with ethanol (1.0 mL) and stirred for 30 min. The solution was then added dropwise to a mixture containing ethanol (8.5 mL), HNO3 (0.2 mL), and distilled water (1.0 mL) under stirring at 400 rpm for 90 min to form the sol. Subsequently, 5.0 g of Zeolite (with a ratio of Zeolite to TiO2 NPs of 95:5 w/w%) was added to the sol and stirred for 30 min. The mixture was aged at room temperature for 24 h, dried at 80 °C for 12 h, and then calcined at 300 °C for 3 h. To compare the catalyst activity, TiO2 NPs were also synthesized using a similar method without the addition of Zeolite. The synthesis procedure is presented in Scheme 1.

Photocatlyst characterization

FTIR spectra of Zeolite, ZnO NPs/Zeolite, and TiO2 NPs/Zeolite are presented in Fig. 1. Strong broad peaks at 3345 cm−1 and 1648 cm−1 correspond to the stretching and bending vibrations of hydroxyl groups in Zeolite. These peaks are also observed in ZnO NPs/Zeolite and TiO2 NPs/Zeolite, albeit with a slight shift in wavenumber to 3344 cm−1 and 1626 cm−1, and 3339 cm−1 and 1623 cm−1, respectively. As can be seen, the peak shift in TiO2 NPs/Zeolite is slightly more than ZnO NPs/Zeolite, showing that the interaction between TiO2 NPs and Zeolite is marginally stronger than ZnO NPs and Zeolite. Additionally, peaks at 1002 cm−1 and 551 cm−1 are attributed to the internal tetrahedral system of Zeolite. Furthermore, peaks at 1439 cm−1 and 1406 cm−1 are associated with Zn-O and Ti-O bonds in ZnO NPs/Zeolite and TiO2 NPs/Zeolite, respectively. The peak at 1002 cm−1 is related to the skeleton vibration of Si(Al)-O- Si(Al) in Zeolite, ZnO NPs/Zeolite, and TiO2 NPs/Zeolite30,31. The presence of these peaks indicates the successful preparation of these composites.

SEM images of ZnO NPs/Zeolite and TiO2 NPs/Zeolite are presented in Fig. 2. ZnO NPs of various shapes and sizes are observed covering the zeolite surface. Zeolite with a porous and uneven structure is of interest as a unique sorbent with a large surface area and a high absorption coefficient32. These many pores in the rhyolite surface are suitable sites for absorbing ZnO NPs or TiO2 Nps through the physisorption process. Anyway, the ZnO NPs exhibit spherical, rod-shaped, and irregular morphologies, with sizes ranging between 70 and 500 nm (Fig. 2a and b). These nanoparticles were impregnated in the zeolite pore and covered the zeolite surface32. On the other hand, Fig. 2c and d depict the presence of TiO2 NPs on the zeolite surface, appearing as rods with lengths ranging from approximately 100 to 300 nm and widths of about 20 to 50 nm. It is evident that the rod-shaped TiO2 NPs have densely covered almost the entire surface of the zeolite.

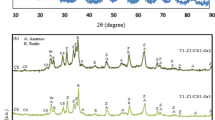

XRD patterns of ZnO NPs/Zeolite and TiO2 NPs/Zeolite are displayed in Fig. 3. The peaks observed at 2 theta values of 7.35, 10.35, 12.6, 16.4, and 22.16 with corresponding lattice planes of 200, 220, 222, 440, and 600 are attributed to Zeolite in both ZnO NPs/Zeolite and TiO2 NPs/Zeolite33. In the case of ZnO NPs/Zeolite (Fig. 3a), peaks at 2 theta angles of 30.1, 33.85, 36.56, 56.60, and 62.95 with lattice planes of 100, 002, 101, 110, and 103 are associated with ZnO NPs34. For TiO2 NPs/Zeolite, peaks at 2 theta values of 25.1, 36.91, 48.04, 53.9, and 55.05 with lattice planes of 101, 004, 200, 105, and 211 are indicative of TiO2 NPs presence (Fig. 3b)35. Moreover, the presence of peaks at 25.1 (101) and 48.04 (200) suggests that the TiO2 NPs exhibit an anatase structure.

The BET analysis of zeolite shows a specific surface area (as, BET) of 12.24 m2 g−1 and a total pore volume of 0.074007 cm3 g−1 at a relative pressure of 0.982. The mean pore diameter was determined to be 24.186 nm. These parameters indicate the porous nature of Zeolite, offering a significant surface area for adsorption and catalytic reactions.

The BET analysis of ZnO NPs/Zeolite revealed a higher specific surface area of 16.651 m2 g−1 and a total pore volume of 0.08193 cm3 g−1 at a relative pressure of 0.981. The mean pore diameter was found to be 19.682 nm. These results suggest that the incorporation of ZnO nanoparticles into Zeolite enhances the surface area available for interactions, potentially improving catalytic performance.

Lastly, the BET analysis for TiO2 NPs/Zeolite showcased remarkable characteristics, with a specific surface area of 148.18 m2 g−1 and a total pore volume of 0.1161 cm3 g−1 at a relative pressure of 0.990. The mean pore diameter was notably smaller at 3.1335 nm. These results indicate the high surface area and finely tuned pore structure of TiO2 NPs/Zeolite, which can facilitate efficient adsorption and degradation of drugs through photocatalytic processes.

Photodegradation procedure

To carry out the photodegradation procedure, the appropriate amount of photocatalyst (ZnO NPs/Zeolite or TiO2 NPs/Zeolite) was introduced into a solution containing AT and ME at specific concentrations. The pH of the solution was adjusted to the optimal level using hydrochloric acid (0.1 M). The mixture was shaken for 45 min in the dark at 150 rpm. Subsequently, an H2O2 solution with the optimum concentration was introduced, and the resulting mixture was exposed to UV light for 60 min. After the photodegradation of AT and ME, the catalyst was separated using centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was analyzed using HPLC to determine the final concentration of AT and ME. The removal percentage (R%) was calculated using the following equation36:

Where, Cf and Ci represent the the final and initial concentration of AT or ME (mg L−1), respectively.

Results and discussion

Type of photocatalyst

The photocatalytic degradation efficiency of AT and ME is significantly influenced by the type of photocatalyst employed. This study investigated the degradation of AT and ME using four different photocatalysts: TiO2 NPs, ZnO NPs, TiO2 NPs/Zeolite, and ZnO NPs/Zeolite. The results demonstrated that the addition of zeolite to both TiO2 NPs and ZnO NPs significantly enhanced the degradation efficiency of AT and ME. Specifically, ZnO NPs exhibited 69.5% and 71.4% degradation of AT and ME, respectively, while ZnO NPs/Zeolite achieved 82.6% and 83.1% degradation for AT and ME, respectively. Similarly, TiO2 NPs resulted in 68.4% and 67.3% degradation of AT and ME, whereas TiO2 NPs/Zeolite demonstrated a substantial increase in degradation efficiency to 83.2% and 82.5% for AT and ME, respectively. The enhanced photocatalytic activity of the zeolite-modified nanoparticles is likely attributed to the following factors: (i) Zeolite’s porous structure provides a larger surface area for the photocatalyst, allowing for more active sites for photocatalytic reactions (ii) The zeolite support may act as a trap for photogenerated electrons, promoting charge separation and reducing electron-hole recombination. (iii) Zeolite exhibits strong adsorption capacity for organic pollutants, potentially enhancing the proximity of the pollutants to the photocatalytic active sites.

Optimization of photodegradation process

In the realm of experimental design, the Box-Behnken design (BBD) stands out as a valuable tool for optimizing processes and understanding complex interactions between multiple variables. The BBD is a response surface methodology (RSM) that utilizes a factorial design with three levels for each factor. The strategy is commonly utilized in various fields, including the optimization of factors in the photodegradation procedures of drugs37. This design enables the efficient study of multiple factors on a response variable, aiding in determining the optimal conditions for achieving desired outcomes38. Unlike full factorial designs, which can become unwieldy with increasing factors, BBDs strategically select combinations of factor levels to achieve optimal information gain with fewer experiments. This not only saves time and reduces costs but also facilitates the rapid identification of optimal conditions for maximizing the photodegradation efficiency of drugs. One of the key advantages of the BBD lies in its ability to estimate both main effects and quadratic interactions between factors39. This is crucial for optimizing processes where interaction effects can significantly impact the response. By exploring the curvature of the response surface, BBDs help identify the optimal factor levels for maximizing or minimizing the desired response40. Furthermore, the BBD’s design structure allows for a balanced distribution of experimental runs, minimizing the potential for bias41. The absence of corner points in the BBD design eliminates the need for extrapolating data, resulting in a more robust and reliable prediction of the response surface. In this study, a Box-Behnken design was created to optimize factors such as drug concentration, catalyst amount, pH, and H2O2 concentration for the photodegradation process. While photodegradation time was not included in this optimization, it will be thoroughly explored in the kinetics section due to its importance.

The designed experiment aimed to optimize the degradation process of AT and ME using ZnO NPs/Zeolite and TiO2 NPs/Zeolite as catalysts. By employing the same design and selective levels for factors, a better comparison of the photocatalytic activity of these catalysts was facilitated. The design included 29 runs for optimizing four selected factors. The levels (minimum, maximum, and center point of each factor were selected based on other published lectures. The runs were carried out in a random order to remove the effects of the unknown parameters. The design and corresponding responses for each drug in the presence of each catalyst were documented in Table 1. Each run within the Box-Behnken design was conducted in triplicate under consistent conditions, with the average degradation of each drug considered as the response variable.

The results were analyzed using ANOVA at a confidence level of 95%. The significance of the effect of each factor or binary interaction in the degradation process of AT and ME was assessed through the p-value obtained using ANOVA. Factors or binary interactions with a p-value less than 0.05 at the 95% confidence level were deemed to have a significant effect on the degradation of drugs.

Optimization of photodegradation process using ZnO NPs/Zeolite

Table 2 shows the ANOVA for the degradation of AT and ME using ZnO NPs/Zeolite as the catalyst. According to the p-value, the quadratic models presented by ANOVA for degrading both drugs are significant (the p-values lower than 0.05)42. Similarly, all four factors in the selective range showed meaningful effects in the degradation of AT and ME in the presence of ZnO NPs/Zeolite as the catalyst. The analysis of binary interactions shows that the interaction between the catalyst amount and the H2O2 concentration significantly degrades both drugs. Other binary interactions for AT degradation did not show a significant effect. However, in ME degradation, the interaction between ME concentration and pH and between pH and catalyst amount also had a significant effect due to the p-values less than 0.05. The three-dimensional diagram of meaningful interactions in the degradation of drugs using ZnO NPs/Zeolite is shown in Fig. 4. However, with the simultaneous increase of the catalyst amount and the H2O2 concentration, R% increases for both drugs. It is clear that by increasing the catalyst amount, the possibility of absorbing light and creating electron-hole pairs increases, which increases the degradation of drugs. Also, by increasing the H2O2 concentration, the possibility of producing free radicals in the solution for the degradation of drugs increases.

The quadratic equation to describe the relationship between factors and interactions with the R% for the degradation of AT and ME in the presence of ZnO NPs/Zeolite is as follows:

Significant binary interaction for degradation of AT and ME using ZnO NPs/Zeolite as the catalyst. Interaction between catalyst amount and H2O2 concentration for the AT degradation (a), ME concentration and pH (b), pH and catalyst amount (c), and catalyst amount and H2O2 concentration for the ME degradation (d).

The adequacy of the equations was assessed by evaluating the R2 and adjusted R2 values, which are compiled in Table 3. The obtained values for the degradation of AT and ME using ZnO NPs/Zeolite as the catalyst exceeded 0.95, indicating a good fit between the equations and the experimental results. Additionally, the predicted R2 values, exceeding 0.85, signify that the models have a strong predictive capability. Notably, the equations highlight that the catalyst amount has the highest coefficient with a positive effect, indicating that an increase in catalyst amount results in higher degradation percentages for AT and ME.

Furthermore, among the binary interactions, the interaction between the catalyst amount and H2O2 concentration exhibited the highest coefficient, indicating that a simultaneous increase in these factors leads to an increased degradation percentage for both drugs. The optimal values for the studied factors were determined based on these results, with drug concentrations, pH, catalyst amount, and H2O2 concentration set at 32 mg L−1, 4.2, 428 mg, and 2.6 mM, respectively. Under these conditions, the predicted degradation percentages for AT and ME were 96.80% and 97.98%, respectively, as shown in Table 4.

Optimization of the photodegradation process using TiO2 NPs/zeolite

The ANOVA evaluation of the results for the degradation of AT and ME with TiO2 NPs/Zeolite as the catalyst is summarized in Table 5. Similar to the previous analysis, all four factors within the specified range exhibited p-values below 0.05, indicating their significant impact on the R%. Examination of binary interactions revealed that three interactions - drug concentration with pH, pH with catalyst amount, and catalyst amount with H2O2 concentration - significantly influenced the degradation of AT and ME in the presence of TiO2 NPs/Zeolite as the catalyst. Additionally, the interaction between drug concentration and H2O2 concentration emerged as another significant factor for ME degradation. Notably, the three-dimensional diagram depicting these significant binary interactions is presented in Fig. 5.

Significant binary interaction for degradation of AT and ME using TiO2 NPs/Zeolite as the catalyst. Interaction between AT concentration and pH (a), pH and catalyst amount (b), catalyst amount and H2O2 concentration (c) for the AT degradation, ME concentration and pH (d), pH and catalyst amount (e), and catalyst amount and H2O2 concentration (f), and ME concentration and catalyst amount (g) for the ME degradation.

The established model was deemed significant for the degradation of both drugs, as indicated by p-values below 0.05, while the lack-of-fit parameter demonstrated insignificance with p-values exceeding 0.05. The quadratic equations derived for the models are as follows:

The R2 and adjusted R2 values in Table 3 validate the suitability of the equations with the obtained results, surpassing 0.95. Additionally, the predicted R2 values for the degradation of AT and ME exceeding 0.85 underscore the models’ efficacy in predicting outcomes. Analysis of the coefficients within the equations revealed that drug concentration held the largest coefficient for AT degradation, emphasizing the significant influence of AT concentration within the specified range. Conversely, in the case of ME degradation, the pH coefficient exhibited the largest negative value, indicating a substantial impact of pH with a drastic decrease in ME degradation with increasing pH.

Furthermore, the most crucial binary interaction with the largest positive coefficient pertained to the interaction between catalyst amount and H2O2 concentration, signifying a substantial increase in the degradation percentage of both drugs with the simultaneous escalation of these factors. Optimal values for factors, including drug concentration, pH, catalyst amount, and H2O2 concentration, were determined to be 33 mg L−1, 4.6, 386 mg, and 2.5 mM, respectively. Under these optimized conditions, the predicted degradation percentages for AT and ME utilizing TiO2 NPs/Zeolite as the catalyst were estimated to be 97.38% and 96.82%, as detailed in Table 4.

The photodegradation kinetic

The kinetics of the degradation process of AT and ME using the catalysts ZnO NPs/Zeolite and TiO2 NPs/Zeolite were investigated utilizing the pseudo-first-order kinetic model. Under optimal conditions determined for each photocatalyst, the appropriate amount of photocatalyst was introduced into a solution containing AT and ME at specific concentrations, and the solution’s pH was adjusted to the optimal level using hydrochloric acid (0.1 M). The mixture was shaken for 45 min in the absence of UV light at a speed of 150 rpm. Subsequently, an H2O2 solution was added, and the resulting mixture was subjected to UV light exposure for a duration ranging from 0 to 60 min. Each experiment was conducted in triplicate.

The pseudo-first-order kinetic model is characterized by the following nonlinear equation36:

Here, x and Cf denote the initial and final concentrations of AT and ME after performing the photodegradation process in the presence of the catalyst, respectively. The variables t, k, and E represent the exposure duration, pseudo-first-order rate constant, and the maximum degradation concentration of AT and ME following the completion of the photodegradation process, respectively. Graphs were generated by plotting Cf against exposure time (Fig. 6). The obtained results revealed rate constants for the photodegradation of AT and ME using ZnO NPs/Zeolite to be 0.064 ± 0.007 min−1 and 0.065 ± 0.004 min−1, while in the presence of TiO2 NPs/Zeolite, they were 0.071 ± 0.007 min−1 and 0.071 ± 0.006 min−1, respectively. These findings indicate that the degradation rate using TiO2 NPs/Zeolite is marginally higher than that with ZnO NPs/Zeolite for both drugs.

Furthermore, the half-life time of degradation was calculated using the equation:

The t1/2 values for the photodegradation of AT and ME were calculated using Eq. (7), revealing a significant difference in the degradation rates between the two catalysts. Table 6 shows that ZnO NPs/Zeolite exhibited a t1/2 of 10.83 min for AT and 10.66 min for ME, while TiO2 NPs/Zeolite demonstrated a faster degradation rate, achieving a t1/2 of 9.76 min for both drugs. The bandgap energy of TiO2 NPs, TiO2 NPs/Zeolite ZnO NPs, and ZnO NPs/Zeolite was determined using the DRS method to be 3.11 eV, 3.23 eV, 3.22 eV, and 3.31 eV, respectively. The results indicated that the band gap energy of TiO2 NPs and ZnO NPs was increased with preparing TiO2 NPs/Zeolite and ZnO NPs/Zeolite. These findings suggest that TiO2 NPs/Zeolite exhibits superior photocatalytic activity compared to ZnO NPs/Zeolite. The observed differences in degradation rates can be due to TiO2 NPs/Zeolite having a smaller bandgap energy compared to ZnO NPs/Zeolite, allowing it to absorb a wider range of wavelengths in the UV light spectrum. This enhanced light absorption leads to a higher generation of electron-hole pairs, driving the photocatalytic degradation process more efficiently. Besides, TiO2 NPs/Zeolite exhibits a higher efficiency in separating electron-hole pairs, reducing the recombination rate and leading to a more effective photocatalytic reaction. Overall, these results highlight the potential of TiO2 NPs/Zeolite as a promising photocatalyst for the degradation of pharmaceutical contaminants in wastewater. The faster degradation rates and shorter half-lives observed with TiO2 NPs/Zeolite compared to ZnO NPs/Zeolite demonstrate its superior performance in removing pharmaceuticals from contaminated water sources.

Elucidating the reactive oxygen species (ROS) responsible

To identify the dominant reactive oxygen species (ROS) responsible for the photocatalytic degradation of AT and ME using the TiO2 NPs/Zeolite and ZnO NPs/Zeolite composite, a series of scavenging experiments were conducted. This approach employed specific chemical scavengers known to selectively quench individual ROS, thereby revealing their relative contributions to the degradation process. The following scavengers were chosen based on their established reactivity with specific ROS, including Benzoquinone (BQ) as an effectively scavenges superoxide radicals (·O2−), Isopropanol (IPA) as a well-known scavenger of hydroxyl radicals (·OH), and Ammonium oxalate (AO) as a scavenger for photogenerated holes (h+). The effects of these scavengers on the photocatalytic degradation of AT and ME were investigated by adding them to the reaction solution before irradiation. The results, presented in Fig. 7, reveal a significant reduction in the degradation rate when IPA is added, indicating that ·OH radicals play a crucial role in the photocatalytic degradation of AT and ME. In contrast, the presence of AO or BQ did not significantly affect the degradation rate, suggesting that h+ and ·O2− have negligible contributions to the degradation process. These findings strongly suggest that ·OH radicals are the primary active species responsible for the efficient degradation of AT and ME by the TiO2 NPs/Zeolite and ZnO NPs/Zeolite composite. This observation is consistent with the proposed mechanism, where the photogenerated electrons from TiO2 NPs or ZnO NPs effectively reduce oxygen molecules to generate ·O2−, which subsequently reacts with H+ to produce ·OH. This detailed investigation into the role of different ROS sheds light on the underlying mechanism of the photocatalytic degradation of AT and ME by the TiO2 NPs/Zeolite and ZnO NPs/Zeolite composite. It further highlights the significance of ·OH radicals in this process, emphasizing the potential of this photocatalyst for effective environmental remediation of AT and ME contamination. The following equations are a suggested mechanism to degrade AT and ME using the prepared photocatalysts:

-

(1)

TiO2 NPs/Zeolite or ZnO NPs/Zeolite (VB) + hν → TiO2 NPs/Zeolite or ZnO NPs/Zeolite (VB) + h + e

-

(2)

H2O2 + e− → OH− + * OH

-

(3)

AT or ME + * OH → Degradation products (CO2, H2O, etc.)

The reusability of the catalysts

The reusability of photocatalysts in degradation methods is essential for promoting environmental sustainability and cost-effectiveness. To assess the reusability of the synthesized catalysts, they were carefully separated from the solution after the photocatalytic degradation process of AT and ME. Subsequently, they were washed with distilled water and dried in an oven at 60 °C for reuse. The results, as presented in Table 7, demonstrate that ZnO NPs/Zeolite can be reused up to 5 times, while TiO2 NPs/Zeolite can be reused up to 6 times without a significant decrease in their activity. These findings suggest that TiO2 NPs/Zeolite exhibit slightly better stability than ZnO NPs/Zeolite in the photocatalytic degradation of drugs.

Comparison with other photocatalysts

The photocatalytic performance of the materials synthesized in this study was evaluated for the degradation of AT and ME and compared to recently reported photocatalysts (Table 8). The data reveal a significant enhancement in the degradation percentage of AT and ME using the newly prepared photocatalysts, suggesting a superior ability to generate electron-hole pairs compared to previously studied materials. Furthermore, the degradation time required for both AT and ME was considerably reduced, indicating faster reaction kinetics. These findings underscore the improved efficiency of the novel photocatalytic materials in facilitating the degradation of these pharmaceuticals, highlighting their potential for more effective water purification applications.

Conclusion

This study successfully synthesized and characterized two novel photocatalysts, TiO2 NPs/Zeolite, and ZnO NPs/Zeolite, for the degradation of AT and ME. The Box-Behnken design effectively identified optimal conditions for maximizing the degradation of both pharmaceuticals, demonstrating the significant influence of pH, catalyst dosage, drug concentration, and H2O2 concentration on the photocatalytic process. Kinetic studies revealed favorable degradation rates and half-lives for both catalysts. A comparative analysis indicated that TiO2 NPs/Zeolite outperformed ZnO NPs/Zeolite in terms of degradation efficiency. TiO2 NPs/Zeolite achieved higher degradation rates with lower consumption, a shorter degradation time, improved reusability, and the ability to function effectively in less acidic conditions. These findings highlight the potential of TiO2 NPs/Zeolite as a promising photocatalyst for the efficient degradation of pharmaceuticals in wastewater, contributing to the development of sustainable and environmentally friendly water treatment technologies.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Mahmood, A. et al. Drugs resistance in Heart diseases. Biochem. Drug Resist. 295–334 (2021).

Goadsby, P. J. et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of Erenumab: Results from 64 weeks of the liberty study. Neurology 96, e2724–e2735 (2021).

Brocker, C. N. et al. Metabolomic profiling of metoprolol hypertension treatment reveals altered gut microbiota-derived urinary metabolites. Hum. Genom. 14, 1–9 (2020).

Waseem, R., Hussein, M. I. H., Salih, T. S. & Ahmed, S. M. Pharmacology of the autonomic nervous system (2023).

Ceolotto, N. et al. A new Wastewater-based epidemiology workflow to estimate community wide non-communicable disease prevalence using pharmaceutical proxy data. J. Hazard. Mater. 461, 132645 (2024).

Yi, M., Sheng, Q., Sui, Q. & Lu, H. β-blockers in the environment: Distribution, transformation, and ecotoxicity. Environ. Pollut. 266, 115269 (2020).

Khasawneh, O. F. S. & Palaniandy, P. Occurrence and removal of pharmaceuticals in wastewater treatment plants. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 150, 532–556 (2021).

Ulvi, A., Aydın, S. & Aydın, M. E. Fate of selected pharmaceuticals in hospital and municipal wastewater effluent: Occurrence, removal, and environmental risk assessment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 75609–75625 (2022).

Iancu, V., Puiu, D. & Radu, G. L. Determination of some beta-blockers in surface water samples (2020).

Sumpter, J. P., Runnalls, T. J., Donnachie, R. L. & Owen, S. F. A comprehensive aquatic risk assessment of the beta-blocker propranolol, based on the results of over 600 research papers. Sci. Total Environ. 793, 148617 (2021).

Zhang, K., Zhao, Y. & Fent, K. Cardiovascular drugs and lipid regulating agents in surface waters at global scale: Occurrence, ecotoxicity and risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 729, 138770 (2020).

Klimaszyk, P. & Rzymski, P. Water and aquatic fauna on drugs: What are the impacts of pharmaceutical pollution? Water Manage. Environment: Case Stud. 255–278 (2018).

Davis, R. B. et al. Quantitation and localization of beta-blockers and SSRIs accumulation in fathead minnows by complementary mass spectrometry analyses. Sci. Total Environ. 741, 140331 (2020).

Ponkshe, A. & Thakur, P. Solar light–driven photocatalytic degradation and mineralization of beta blockers propranolol and atenolol by carbon dot/TiO2 composite. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 1–17 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Mechanism of bicarbonate enhancing the photodegradation of β-blockers in natural waters. Water Res. 197, 117078 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Targeted degradation of refractory organic compounds in wastewaters based on molecular imprinting catalysts. Water Res. 203, 117541 (2021).

Chen, F. et al. Catalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin by a visible-light-assisted peroxymonosulfate activation system: Performance and mechanism. Water Res. 173, 115559 (2020).

Abu-Dief, A. M. & Mohamed, W. Development of nanomaterials as photo catalysts for environmental applications. Curr. Catal. 9, 128–137 (2020).

Abdullah, T. A. et al. A critical review of the photocatalytic degradation of pharmaceutical residues by a TiO2-based photocatalyst. Hung. J. Ind. Chem. 51, 65–75 (2023).

Sawunyama, L., Oyewo, O. A., Seheri, N., Onjefu, S. A. & Onwudiwe, D. C. Metal oxide functionalized ceramic membranes for the removal of pharmaceuticals in wastewater. Surf. Interfaces 102787 (2023).

Saeed, M., Muneer, M., Haq, A., Akram, N. & Photocatalysis An effective tool for photodegradation of dyes—A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 293–311 (2022).

Saravanan, A., Kumar, P. S., Jeevanantham, S., Anubha, M. & Jayashree, S. Degradation of toxic agrochemicals and pharmaceutical pollutants: Effective and alternative approaches toward photocatalysis. Environ. Pollut. 298, 118844 (2022).

Hussain, S. M. et al. Emerging aspects of photo-catalysts (TiO2 & ZnO) doped zeolites and advanced oxidation processes for degradation of azo dyes: A review. Curr. Anal. Chem. 17, 82–97 (2021).

Hu, G. et al. Recent developments and challenges in zeolite-based composite photocatalysts for environmental applications. Chem. Eng. J. 417, 129209 (2021).

Wang, Y., Wang, C., Wang, L., Wang, L. & Xiao, F. S. Zeolite fixed metal nanoparticles: New perspective in catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 54, 2579–2590 (2021).

Sun, Q., Wang, N. & Yu, J. Advances in catalytic applications of zeolite-supported metal catalysts. Adv. Mater.33, 2104442 (2021).

Mahdavi Far, R., Van der Bruggen, B., Verliefde, A. & Cornelissen, E. A review of zeolite materials used in membranes for water purification: History, applications, challenges and future trends. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 97, 575–596 (2022).

Pan, Y. et al. Functional Ag-doped coralloid titanosilicate zeolite (CTS-Ag) for efficiently catalytic and photodegradative removal of free cyanides and copper/zinc-cyanide complexes in real wastewater. J. Alloys Compd. 926, 166848 (2022).

Abadi, M. A. A., Masrournia, M. & Abedi, M. R. Simultaneous extraction and preconcentration of three beta (β)-blockers in biological samples with an efficient magnetic dispersive micro-solid phase extraction procedure employing in situ sorbent modification. Microchem. J. 163, 105937 (2021).

Alswata, A. A. et al. Preparation of zeolite/zinc oxide nanocomposites for toxic metals removal from water. Results Phys. 7, 723–731 (2017).

Liu, X., Liu, Y., Lu, S., Guo, W. & Xi, B. Performance and mechanism into TiO2/Zeolite composites for sulfadiazine adsorption and photodegradation. Chem. Eng. J. 350, 131–147 (2018).

Wedajo, T., Mekonnen, A. & Alemu, T. Preparation and application of zeolite-zinc oxide nano composite for nitrate removal from groundwater. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 21, 277–291 (2023).

Bessa, R. A. et al. Hierarchical zeolite based on multiporous zeolite A and bacterial cellulose: An efficient adsorbent of Pb2+. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 312, 110752 (2021).

Abdelhakim, H. K., El-Sayed, E. & Rashidi, F. B. Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles with antimicrobial, anticancer, antioxidant and photocatalytic activities by the endophytic Alternaria tenuissima. J. Appl. Microbiol. 128, 1634–1646 (2020).

El Bendali, A. et al. The electrochemical and structural changes of phosphorus-doped TiO2 through in situ Raman and in situ X-ray diffraction analysis. ACS Omega 9, 14911–14922 (2024).

Ghorbani, M. et al. Crafting an innovative bimetallic MOF-on-MOF/TiO2 composite for effective removal of Imatinib anticancer agent through adsorption and photodegradation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 336, 126227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2023.126227 (2024).

Mohammadi, P. et al. Dispersive micro solid-phase extraction with gas chromatography for determination of Diazinon and Ethion residues in biological, vegetables and cereal grain samples, employing D-optimal mixture design. Microchem. J. 160, 105680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2020.105680 (2021).

Ghorbani, M. et al. Optimization and synthesis of a novel sorbent composite based on magnetic chitosan-amine-functionalized bimetallic MOF for the simultaneous dispersive solid-phase microextraction of four aflatoxins in real water, herbal distillate, and food samples. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 415, 5681–5694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-023-04842-0 (2023).

Latif, A. et al. Optimized degradation of bisphenol A by immobilized laccase from trametes versicolor using box-behnken design (BBD) and artificial neural network (ANN). J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10, 107331 (2022).

Silva, V. & Cardoso, J. S. Response Surface Methods-Theory, Applications and Optimization Techniques: Theory, Applications and Optimization Techniques. (BoD–Books on Demand, 2024).

Pandey, A. K. & Sara, U. S. Quality by design approach for optimization of 5-fluorouracil microbeads using box–behnken design and desirability function for colon targeting. J. Pharm. Innov. 18, 2054–2065 (2023).

Ghorbani, M. et al. Investigation and health risk assessment of nitrate ion, nitrite ion, and phthalate esters in herbal distillates produced by Iranian companies. Fine Chem. Eng. 1–23 (2024).

Wang, Y., Niu, J., Gao, X. & Zhang, Y. Synergetic tuning of photocatalytic activity and photostability of Ag3PO4 via yttrium doping, carbon quantum dots and BiVO4 for atenolol degradation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 533, 147458 (2020).

Ramasamy, B., Jeyadharmarajan, J. & Chinnaiyan, P. Novel organic assisted Ag-ZnO photocatalyst for atenolol and acetaminophen photocatalytic degradation under visible radiation: Performance and reaction mechanism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 39637–39647 (2021).

Rajeshwari, M. R. et al. Enhanced photo-Fenton assisted photocatalytic degradation of atenolol using a novel rGO embedded double Z-scheme nano-heterojunction: Mechanism, kinetics and toxicity studies. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 115, 402–415 (2022).

Bhuvaneswari, R., Jeyanthi, J. & Kumar, M. Visible light assisted degradation of atenolol by Fe-TiO2: Synthesis, characterization, optimization and mechanism. Optik 239, 166658 (2021).

Hojamberdiev, M., Czech, B., Göktaş, A. C., Yubuta, K. & Kadirova, Z. C. SnO2@ ZnS photocatalyst with enhanced photocatalytic activity for the degradation of selected pharmaceuticals and personal care products in model wastewater. J. Alloys Compd. 827, 154339 (2020).

Leong, K. et al. Sunlight mediated enhanced removal of metoprolol using graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4). Mater. Res. Found. 29.

Avilés-García, O. et al. Removal of metoprolol by means of photo-oxidation processes. Catal. Today 397, 562–573 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their appreciation to the Research Council of Islamic Azad University of Quchan, Iran for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sara Sarabyar: Writing e original draft, Investigation, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Resources.Afshin Farahbakhsh: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing e review & final editing. Hamzeh Ali Tahmasebi: Analysis, Writing e review. Behrooz Mahmoodzadeh Vaziri : Investigation, Writing e review. Susan Khosroyar: Investigation, Writing e review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sarabyar, S., Farahbakhsh, A., Tahmasebi, H.A. et al. Enhancing photocatalytic degradation of beta-blocker drugs using TiO2 NPs/zeolite and ZnO NPs/zeolite as photocatalysts: optimization and kinetic investigations. Sci Rep 14, 27390 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73888-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73888-6