Abstract

The development of next-generation materials such as hBN and Ga2O3 remains a topic of intense focus owing to their suitability for efficient deep ultraviolet (DUV) emission and power electronic applications. In this study, we combine p-type hBN and n-type Ga2O3, forming a pseudo-vertical pn hBN/Ga2O3 heterojunction device. Rectification ratios > 105 (300 K) and \(\:\sim\)400 (475 K) are observed and are amongst the highest values reported to date for ultra-thin hBN-based pn junctions. The measured current under forward bias is ~2 mA, which we attribute to the shallow Mg acceptor level (60 meV), and 0.2 µA at −10 V. Critically, device performance remains stable and highly repeatable after a multitude of temperature ramps to 475 K. Capacitance-voltage measurements indicate widening the depletion region under increasing reverse bias voltage and a built-in voltage of 2.34 V is recorded. The hBN p-type characteristic is confirmed by Hall effect, a hole concentration of \(\:7\times\:{10}^{17}\) cm−3 and mobility of 24.8 cm2/Vs is achieved. Mg doped hBN resistance reduces by >108 compared to intrinsic material. Future work shall focus on the optical emission properties of this material system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the discovery of two-dimensional materials in 20041, this emerging material category has captured the attention of scientists owing to their array of superlative properties. Hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) is a forerunner for a range of applications in relation to its superior thermal conductivity, chemical stability, high remote optical phonon energies, and flat surface without dangling bonds2,3,4. For these reasons, hBN is considered at the very least to be a suitable next-generation dielectric applications, providing high resistance and enhanced thermal dissipation while exerting minimum reduction in channel mobility for semiconductor devices ranging from Si logic to GaN HEMT power devices that are known to particularly suffer from joule heating effects5.

Research groups are also now exploring whether hBN can be used as an active material beyond dielectric and thermal dissipation applications. Recently it has been shown that hBN can be p-type doped using Mg (Ea~30 meV), and recently, n-type has been demonstrated through the use of Ge-O doping, and later combined with p-GaN forming a pn heterojunction device6. Furthermore, hBN is a efficient DUV emitter ×500 greater than AlN which suffers from a low internal quantum efficiency (< 3%) at < 250 nm and is used for commercial solid-state DUV emissive devices7,8,9. For example, hBN has a reported room-temperature quantum efficiency of ∼60% at UV-C wavelengths10.

Along with AlGaN, diamond, and boron nitride, gallium oxide (Ga2O3) is also one of the fourth-generation ultra-wide bandgap (UWBG) materials with a 4.8 eV band gap and is a promising candidate for several classes of power electronics, solar cells, solar-blind UV photodetectors, and even gas sensors11,12,13,14,15.

Specifically, Ga2O3 has as high critical electric field (Ecrit >8 MV/cm) and an impressive Baliga figure of merit value of 3124 (relative to Silicon) permitting Ga2O3-based power devices in achieving reduced power losses16 compared to conventional semiconductor materials. Importantly, device quality Ga2O3 can be grown heteroepitaxially on sapphire substrate facilitating technology scaling17,18,19. Unfortunately, Ga2O3 performance is hindered by low thermal conductivity, resulting in faster device degradation. Like many wide bandgap materials, Ga2O3 suffers from asymmetric doping where n-type is achievable, however p-type doping is non-trivial14. Though β-Ga2O3 is an indirect bandgap material, it possesses a direct gap only 29 meV higher, suggesting DUV emission maybe possible if high quality pn junctions can be fabricated20.

This naturally leads one to consider the formation of hBN/Ga2O3 heterostructures where the aforementioned challenges can be overcome owing to their complementary material properties.

In this article, we show that Mg doped hBN (ambient wet-transfer process) on n-type Ga2O3 can lead to the formation of high quality stable pn junction diodes. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a pn heterojunction formed between multilayer p-type hBN and n-type Ga2O3.

Methods

hBN growth

A homemade atmospheric pressure chemical vapor deposition (APCVD) system with three heating zones was used for hBN growth (Figure S2a). The system includes two internal quartz tubes, with each tube hosting ammonia borane (99.7% purity) in Zone 1 and Mg3N2 dopant precursor (99.6% purity) in Zone 2. Cu foil (99.7% purity, 30 μm thick) was electrochemically polished using a standard process21. Next, Cu was annealed in an Ar/H2 ambient (300 SCCM, 4 N purity) for 1 h at 1000 °C for enlarged Cu grains at 93.3 kPa. Figure S1 illustrates the time-temperature process in each reaction zone during growth. Vacuum base pressure was 7\(\:\:\times\:{10}^{-2}\) Pa prior to growth.

During hBN growth, ammonia borane (30 mg) is held at 90 °C and a zone 3 temperature of 1050 °C is used. The doping precursor (30 mg) was rapidly ‘turned-on’ reaching 850 °C after \(\:\sim\)5 minutes of hBN growth (from a set point of 500 °C). Growth duration was 1 h, then Ar/H2 was used as a protective gas and the system was allowed to naturally cool to room temperature. hBN film thickness is 10 nm. Thereafter, we apply a standard wet chemical process for hBN transfer to Ga2O322.

n-type Ga2O3growth

The heteroepitaxial Ga2O3 layer on c-plane sapphire is 400 nm thick grown by metal organic chemical vapour deposition. Tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) gas was used for in-situ n-type doping during growth, further details are published here17. The electron carrier concentration is \(\:\sim\)1 \(\:\times\:\) 1018 cm−3 determined by Hall measurement.

Device fabrication

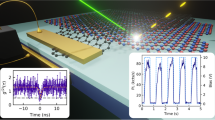

The pn junction is fabricated through a sequence of lithographic, etch and lift-off process steps. Inductiviely coupled reactive ion etching (ICPRIE) was performed using Ar gas. A Ti/Al/Ni/Au metal stack with 20/300/40/50 nm thicknesses were deposited by E-Gun on an n-type Ga2O3 epilayer followed by rapid thermal anneal to obtain an Ohmic contact. Then, Pt was deposited on hBN similarily to obtain the p-electrode contact (Fig. 3a). The fabrication process flow is shown in Fig. 1a, device structure and final layout are shown in Fig. 1b,c.

Physical analysis and electrical test

Morphological and thickness measurements were performed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), optical microscopy (OM) and atomic force microscope (AFM). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was used to determine B: N stoichiometric ratio. Raman spectra (JadeMat DPL 532 nm laser) was obtained with a 100 mW laser and 20 s integration time. X-ray diffraction (XRD, (Cu Kα, λ = 1.54 Å)) was used to confirm hBN crystallinity. Ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) was performed using a ULVAC-PHI 5000 Versaprobe II system (He UV light source) with an energy resolution of 0.02 eV (beam diameter 300 μm) to locate Fermi level position.

The Mg acceptor level was identified through temperature dependent Hall effect analysis on a reference sample transferred onto sapphire substrate. Capacitance-Voltage (C-V) and Current-Voltage (I-V) analysis is performed by a Solartron 1260 A impedance system and a HP4140B, respectively. An ezHEMS system with a 1 T field switching capability was employed for Hall effect analysis (Van der Pauw configuration).

Results and discussion

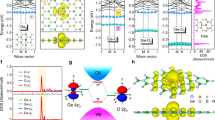

In Fig. 2a–d, XRD, XPS, Raman and UV-Vis data is presented. Figure 3a shows a singular hBN diffraction peak from the (002) plane indicating good crystallinity (bottom panel). For the Mg doped sample, (top panel) a similar result is obtained. For hBN doped and undoped material, diffraction peaks occur at 26.0 ° and 26.19 ° respectively. This may be linked to induced crystal strain as Mg atoms occupy B sites22,23,24. Full width half maximum (FWHM) values of intrinsic and doped hBN register at 1.4 ° and 1.45 ° respectively. Intrinsic hBN possesses triangular domains (lateral edge) that vary from 2 to 30 \(\:\mu\:m\)25,26,27 depending on growth conditions25. In Fig. S2b Mg doped hBN domains are similarily triangular in nature and have an \(\:\sim\)1.5 \(\:\mu\:m\) lateral edge, in other regions values up to 6 \(\:\mu\:m\) are seen. A nucleation density of \(\:\sim\)104/mm2 is calculated. These values are \(\:\times\:10\:\)higher than our undoped hBN material. SEM analysis was performed after hBN doping on Cu foil (reference sample), confirming a clean surface devoid of particles (Fig. S2c). In Fig. S2d an AFM image illustrates the Mg doped hBN layer on Ga2O3 substrate. Surface roughness is approximately 0.8 nm. Residual photoresist is also observed.

To confirm Mg incorporation, Raman spectroscopy was performed. In Fig. 3b, (bottom panel) a single E2g vibrational mode for undoped hBN is recorded at 1370 cm− 1. For the Mg doped sample (top panel) a 2nd mode appears at 1357 cm− 1. This may relate to Mg incorporation on B sites as similar secondary peaks at 1347 cm− 1 and 1363 cm− 1 are reported in22,28.

In Fig. 2c,d the XPS spectra of Mg doped hBN is presented. The B1s and N1s binding energies are 190.5 and 398.4 eV, in agreement with published values and the N/B ratio is 1.0622. UV-VIS absorption is used to evaluate bandgap and impurity incorporation. Figure 2e shows a clear band edge absorption peak for both samples at \(\:\sim6.0\:\)eV. In addition, a shoulder appears that we ascribe to Mg impurity incorporation.

In Fig. 2f, UPS demonstrates that EF is 1.8 eV from valence band edge after a 5 s 1 kV Ar sputter taken from Mg doped hBN reference sample on Cu foil grown under indentical conditions. The EF position is deeper than expected, and is clearly p-type, compared to our previous works where EF is midgap for intrinsic hBN material26. This maybe linked to doping induced defects or Fermi level pinning (FLP) effects which are known to occur in 2D materials. For example, EF in n-type 2D hBN is 1.9 eV from Ec as determined by UPS including a built-in voltage of 3.11 V when combined with p-GaN6.

Electrical measurements (I-V) were performed to confirm sample conductivity change after doping, shown in Fig. 3a. Intrinsic hBN has a resistance \(\:>\)109 Ω cm29 reducing to 0.36 Ω cm after Mg incorporation (Four point probe method). An Arrhenius plot is used in Fig. 3b to study the influence of temperature on carrier concentration and to extract an activation energy of 60 meV, similar to Ea ’s reported in7,22,30. A carrier concentration of 7 \(\:\times\:\:\)1017 cm−3 and a hole mobility of 24.8 cm2/Vs is measured at 300 K including a positive Hall voltage.

The I-V characteristics of the p-hBN/n-Ga2O3 junction measured from 300 to 475 K can be observed in Fig. 4a. A rectification ratio (RR) of 2.6\(\:\times\:\)104 at 300 K and \(\:\sim\)400 at 475 K are recorded and are among the highest values seen for ultra-thin hBN based pn junctions. A cut-in voltage (Vcut) of 2.05 V is extrapolated. Leakage current under reverse bias (−10 V ) is 0.2 µA at 300 K rising to 2\(\:\times\:\)10−4 A at 475 K, increasing with reverse bias voltage. This suggests that a current leakage path exists owing to the presence deep defect levels in the depletion layer. In Fig. 4b we plot saturation current I0 (-5 V) versus 1000/T where a 0.44 eV activation process is found, which may correlate with defects within hBN31. At forward bias, all I-V curves display a high RON originating from either a high hBN contact resistance, which is not optimized or a lateral current pathway in in n-type Ga2O3 (ND\(\:\sim\) 1\(\:\times\:\)1018 cm−3) which typically has low mobility. Ga2O3 ohmic contact resistance is typically < 10−5 ohm cm218. S. Majety32 demonstrated BN/AlGaN pn junctions with comparable properties. Here, leakage current was 3 µA at -10 V, however these BN films were considerably thicker, similarly in24.

After cool-down, the device was remeasured to confirm its stability, shown in Fig. 4c and current saturation in the linear I-V plot (> 7 V ) is owing to measurement system limitation. The pn junction remains highly functional, and rectification has increased to 2.6 \(\:\times\:{10}^{5}\). Diode RON before and after temperature ramping is 2\(\:\times\:\)103 Ω reducing to 400 Ω respectively. We attribute these improvements to reduced contact resistance. Likewise, a number of other devices were also tested at 300 K producing RRs of \(\:\sim\) 104, leakage currents < 1 \(\:\mu\:\)A and RON between 200 and 400 Ω. Owing to the large series resistance, the ideality factor is obtained using Shockley equation in the sub-threshold region only (Table 1). High values of 3.77 reducing to 2.0 at 475 K suggests thermal activation is occurring as resistance reduces at elevated temperatures. Alternatively, high values that reduce with increasing temperature have been linked to tunneling through ultra-thin barriers33.

C-V measurements are plotted in Fig. 4d from 1 to 6 MHz after temperature ramping at 300 K. The forward voltage is limited to 4 V as beyond this point diffusion capacitance dominates. The measured capacitance reduces with increasing reverse bias voltage indicating a widening of the depletion region. Under forward bias, capacitance increases owing to space charge accumulation at the depletion edge. At lower modulation frequencies total capacitance increases consecutively. This behaviour is typically associated with trapping/detrapping behaviour in the depletion region as at higher frequencies these states cannot follow the AC signal. The calculated junction capacitance is 0.18 nF in close agreement with those values depicted in Fig. 4d at zero bias.

In Fig. 4d built-in potential (Vbi) and doping concentration (NA) can be determined assuming an abrupt pn+ junction (Eq. 1). Extrapolation from 1/C2 yields a \(\:{v}_{bi}\) of 2.34 V from the linear gradient, which is close to the cut-in voltage. The 1/C2 gradient is non-linear implying a non-uniform doping profile at the pn junction interface. A net NA concentration of 7.0 \(\:\times\:\)1017 cm− 3 has been extracted from the slope of the linear segment when ND is 1.0 \(\:\times\:\)1018 cm− 3 (Ga2O3 doping level). These findings are in agreement with Hall effect measurements.

(ΔEv < ΔEc34)

Where A is the effective junction area (5.8\(\:\times\:{10}^{-8}\) m2), V is the applied voltage, \(\:\epsilon\:\) is the permittivity of hBN (\(\:{\epsilon\:}_{r}=3.5)\) and Ga2O3 (\(\:{\epsilon\:}_{r}=9.5)\) and NA is the net hole concentration. Richardson constant A* is taken as 3.12 × 105 Am−2 K−235.

For barrier height (φB) elucidation36, \(\:{v}_{d0}\) = \(\:{v}_{bi}+\:\left(\raisebox{1ex}{$kT$}\!\left/\:\!\raisebox{-1ex}{$q$}\right.\right)\) denotes the diffusion voltage at zero bias, and \(\:{v}_{p}\) = (\(\:{k}_{B}\)T⁄q)\(\:ln\left(\raisebox{1ex}{${N}_{v}$}\!\left/\:\!\raisebox{-1ex}{${N}_{A}$}\right.\right)\) represents the theoretical Fermi level position above the valence band in a neutral region of the semiconductor (Eq. 2). Taking Nv as 2.1\(\:\times\:{10}^{19}\) cm−337, φB equates to 2.47 eV in close agreement with \(\:{v}_{bi}\). φB has also been evaluated using Eq. 3, here the barrier height is recorded at a lower value of 0.86 V. Differences in barrier heights from I-V and C-V methods are well known and have been linked to effects such as interfacial barrier height inhomogeneity, deep defect levels or interfacial charge38,39.

The intrinsic hBN/Ga2O3 band alignment (direct growth) has been studied by XPS33,40 revealing a staggered type-II band alignment. Using Anderson’s method where the electron affinity of hBN and Ga2O3 are 2.0 eV and 4.0 eV26,41, respectively, we estimate the theoretical Vbi as 2.2 eV in agreement with the 1/C2 value (Fig. 5). The larger ΔEc should hinder the movement of electrons from Ga2O3 into hBN suggesting current transport may be dominated by holes moving from p-hBN to n-Ga2O3.

Conclusion

Pseudo-vertical high performing hBN/Ga2O3 pn junctions have been demonstrated. Rectification ratios > 105 and leakage currents < 0.2 \(\:\mu\:\)A are measured at 300 K and devices continue to operate reliably after high temperature ramping to 475 K. C-V analysis indicates device performance follows classical pn junction behaviour as bias voltage varies. The hBN carrier concentration is \(\:\sim\)7\(\:\times\:\)\(\:{10}^{17}\) cm−3 in reasonable agreement with C-V analysis. UPS analysis suggests FLP effects are present, and the theoretical Vbi is in good agreement with the measured value. We expect further performance gains as hBN doping and growth improves.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

12 December 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81771-7

References

Butler, S. Z. et al. Progress, challenges, and opportunities in two-dimensional materials beyond graphene. ACS Nano 7, 2898–2926 (2013).

Amalia, W., Nurwantoro, P. & Sholihun Density-functional-theory calculations of structural and electronic properties of vacancies in monolayer hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN). Comput. Condens. Matter 18, e00354 (2019).

Gunder, D., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Witte, G. Van der waals bound organic/2D insulator hybrid structures: Epitaxial growth of acene films on hBN (001) and the influence of surface defects. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 38757–38767 (2020).

Li, L. et al. A minireview on chemical vapor deposition growth of wafer-scale monolayer: H -BN single crystals. Nanoscale 13, 17310–17317 (2021).

Mao, J. Y. et al. A Van der waals integrated damage-free memristor based on layered 2D hexagonal boron nitride. Small 18, 2106253 (2022).

Lu, S. et al. Towards n-type conductivity in hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Commun. 13, 3109 (2022).

Dahal, R. et al. Epitaxially grown semiconducting hexagonal boron nitride as a deep ultraviolet photonic material. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 211110 (2011).

Kinoshita, T. et al. Deep-ultraviolet light-emitting diodes fabricated on AlN substrates prepared by hydride vapor phase epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Express 5, 122101 (2012).

Song, S. B. et al. Deep-ultraviolet electroluminescence and photocurrent generation in graphene/hBN/graphene heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 12, 7134 (2021).

Laleyan, D. A. et al. Epitaxial hexagonal boron nitride with high quantum efficiency. APL Mater. 11, 051103 (2023).

Hu, K. H. et al. γ-Ga2O3 nanocrystals electron-transporting layer for high-performance perovskite solar cells. Sol RRL 3, 1900201 (2019).

Tak, B. R. et al. Photovoltaic and flexible deep ultraviolet wavelength detector based on novel β-Ga2O3/muscovite heteroepitaxy. Sci. Rep. 10, 16098 (2020).

Lin, C. H. & Lee, C. T. Ga2O3-based solar-blind deep ultraviolet light-emitting diodes. J. Lumin. 224, 117326 (2020).

Huang, C.Y et al. Heteroepitaxially grown homojunction gallium oxide PN diodes using ion implantation technologies, Materials Today Advances, 22, 100499, (2024)

Zhai, H., Wu, Z. & Fang, Z. Recent progress of Ga2O3-based gas sensors. Ceram. Int. 48, 24213–24233 (2022).

Jahdi, S., Kumar, A. S., Deakin, M., Taylor, P. C. & Kuball, M. β-Ga2O3 in power electronics converters: opportunities & challenges. IEEE Open. J. Power Electron. 5, 1–11 (2024).

Tarntair, F. G. et al. Material properties of n-Type β-Ga2O3 epilayers with in situ doping grown on sapphire by metalorganic chemical vapor deposition. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2300679 (2024).

Yang, D., Kim, B., Eom, T. H., Park, Y. & Jang, H. W. Epitaxial growth of alpha gallium oxide thin films on sapphire substrates for electronic and optoelectronic devices: progress and perspective. Electron. Mater. Lett. 18, 113–128 (2022).

Wen, Z. et al. Investigation of Si incorporation in (010) β-Ga2O3 films grown by plasma-assisted MBE using diluted disilane as Si source and suboxide Ga2O precursor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 124, 122101 (2024).

Mengle, K. A., Shi, G., Bayerl, D. & Kioupakis, E. First-principles calculations of the near-edge optical properties of β-Ga2O3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 212104 (2016).

Li, Y. J., Tu, K. N. & Chen, C. Tensile properties of < 111>-oriented nanotwinned Cu with different columnar grain structures. Materials (Basel) 13, 1–11 (2020).

Sun, F. et al. P-Type conductivity of hexagonal boron nitride as a dielectrically tunable monolayer: Modulation doping with magnesium. Nanoscale 10, 4361–4369 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. P-type hexagonal boron nitride films with bis (cyclopentadienyl) magnesium as a doping gas in halide vapor phase epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 202102 (2023).

Mballo, A. et al. Towards p-type conduction in hexagonal boron nitride: Doping study and electrical measurements analysis of hBN/AlGaN heterojunctions. Nanomaterials 11, 211 (2021).

Stehle, Y. et al. Synthesis of hexagonal boron nitride monolayer: control of nucleation and crystal morphology. Chem. Mater. 27, 8041–8047 (2015).

Marye, S. A., Kumar, R. R., Useinov, A. & Tumilty, N. Thermal stability, work function and Fermi level analysis of 2D multi-layered hexagonal boron nitride films. Microelectron. Eng. 283, 112106 (2024).

Song, X. et al. Chemical vapor deposition growth of large-scale hexagonal boron nitride with controllable orientation. Nano Res. 8, 3164–3176 (2015).

Khalil, L. et al. High p doped and robust band structure in Mg-doped hexagonal boron nitride. Nanoscale Adv. 5, 3225–3232 (2023).

Le Thi, H., Abate Marye, S. & Tumilty, N. AC conductivity of hBN thin film on Si(111): a high temperature study. J. Appl. Phys. 132, 195101 (2022).

Jiang, H. X. & Lin, J. Y. Hexagonal boron nitride for deep ultraviolet photonic devices. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 29, 084003 (2014).

Weston, L., Wickramaratne, D., Mackoit, M., Alkauskas, A. & Van de Walle, C. G. Native point defects and impurities in hexagonal boron nitride. Phys. Rev. B 97, 214104 (2018).

Majety, S. et al. Epitaxial growth and demonstration of hexagonal BN/AlGaN p-n junctions for deep ultraviolet photonics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 061121 (2012).

Luongo, G. et al. I-V and C-V characterization of a high-responsivity graphene/silicon photodiode with embedded MOS capacitor. Nanomaterials 7, 158 (2017).

Fares, C., Ren, F. & Pearton, S. J. Temperature-dependent electrical characteristics of β-Ga2O3 diodes with W Schottky contacts up to 500°C. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 8, Q3007–Q3012 (2019).

Ortiz, W., Ramirez, N. J., Barrionuevo, D., Bhattarai, M. K. & Feng, P. Characterization of 2D boron nitride nanosheets with hysteresis effect in the schottky junctions. Nano Express. 2, 010020 (2021).

Chirakkara, S. & Krupanidhi, S. B. Study of n-ZnO/p-Si (100) thin film heterojunctions by pulsed laser deposition without buffer layer. Thin Solid Films 520, 5894–5899 (2012).

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Electric Field Effect Atomically Thin Carbon Films 306, 666–669 (2016).

Tung, R. T. Recent advances in schottky barrier concepts. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 35, 1–138 (2001).

Hacke, P. et al. Schottky barrier on n-type GaN grown by hydride vapor phase epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2678, 2676–2678 (1993).

Rama, V. K. R. et al. Characteristics of Vertical Ga2O3 Schottky junctions with the interfacial hexagonal boron nitride film. ACS Omega 7, 26021–26028 (2022).

Patrick, H. et al. Valence and conduction band offsets in AZO/Ga2O3 heterostructures. Vacuum 141, 103–108 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science and Technology Council (Taiwan, R.O.C.) under Grant Nos. 112-2622-E-A49 -011, 112-2221-E-A49 -069 -MY3, 112-2622-8-A49-013-SB, 111-2923-E-A49-003-MY3, 110-2222-E-009 -006-MY3 and 111-2622-8-A49-018-SB.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A.M, hBN growth, doping, device test, manuscript drafting and editing. X.Y.T: Device fabrication and test. R.R.K: hBN growth, doping and measurement. F.G.T: Ga2O3 growth and doping. N.T and R.H.H, conceptualization, funding acquistion, analysis and confirmation, manuscript drafting, project supervision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in Figure 3 panel b, where the y-axis was presented on a linear scale instead of a log scale. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Marye, S.A., Tsai, XY., Kumar, R.R. et al. A hBN/Ga2O3 pn junction diode. Sci Rep 14, 23484 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73931-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73931-6