Abstract

In the primary visual cortex area V1 activation of inhibitory interneurons, which provide negative feedback for excitatory pyramidal neurons, can improve visual response reliability and orientation selectivity. Moreover, optogenetic activation of one class of interneurons, parvalbumin (PV) positive cells, reduces the receptive field (RF) width. These data suggest that in V1 the negative feedback improves visual information processing. However, according to information theory, noise can limit information content in a signal, and to the best of our knowledge, in V1 signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) has never been estimated following either pyramidal or inhibitory neuron activation. Therefore, we optogenetically activated pyramidal or PV neurons in the deep layers of cortical area V1 and measured the SNR and RF area in nearby pyramidal neurons. Activation of pyramidal or PV neurons increased the SNR by 267% and 318%, respectively, and reduced the RF area to 60.1% and 77.5%, respectively, of that of the control. A simple integrate-and-fire neuron model demonstrated that an improved SNR and a reduced RF area can increase the amount of information encoded by neurons. We conclude that in V1 activation of pyramidal neurons improves visual information processing since the location of the visual stimulus can be pinpointed more accurately (via a reduced RF area), and more information is encoded by neurons (due to increased SNR).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neural circuits in the sensory cortex are designed to perform efficient sensory information encoding and transfer1. In the cortex, excitatory pyramidal neurons are the output cells since they are the only cell type that provides significant connections with other brain areas. Meanwhile, virtually all inhibitory neurons form local connections. Pyramidal neurons form a recurrent excitatory network, and negative feedback is provided by inhibitory interneurons. Such feedback is necessary for whole-network stability to prevent runaway excitation; therefore, cortical circuits typically function as inhibition stabilized networks (ISNs) that allow very efficient encoding and storage of sensory information2,3. The primary visual cortex (area V1) was among the first experimentally demonstrated examples of ISN4,5. In V1, the function of inhibitory interneurons is not limited to the prevention of runaway excitation; the activation of interneurons can enhance visual information processing by increasing orientation selectivity and visual response reliability6,7,8,9,10. In addition, stimulation of inhibitory parvalbumin interneurons reduces the RF width in the horizontal direction, thus potentially sharpening vision11. However, according to information theory, noise limits the speed of information transfer and information content in a signal12. Surprisingly, to the best of our knowledge, no estimates of the SNR changes following interneuron activation have been made. Although in the cortex inhibitory interneurons can be activated by pyramidal neurons of all layers, pyramidal neurons located in deep layers V and VI form connections with many interneurons across all layers and activation of these pyramidal neurons can lead to inhibition across multiple layers13,14; nevertheless, the only reported effect of optogenetic layer VI pyramidal neuron excitation is a change in response gain without any effect on orientation tuning selectivity13. However, in this study, no data on the SNR, RF width or area were provided. Therefore, we tested whether optogenetic activation of pyramidal or inhibitory PV neurons in deep layers of area V1 could induce sufficient inhibition to produce changes in the SNR and RF area. We demonstrated that this is indeed the case and that these changes increase the amount of information encoded by nearby pyramidal neurons.

Results

We activated V1 neurons by employing optogenetic methods. To this end, modified channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) with the H134R mutation (ChR2-H134R15) was expressed in pyramidal or PV neurons following AAV virus injections into the rat visual cortex at depths of ~ 1000 μm (Fig. 1).

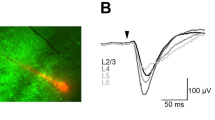

ChR2 channels were activated by 465 nm LED light delivered ~ 400 μm above the recording site via a 100 μm wide optical fiber attached to the recording tetrode (Fig. 2). ChR2-H134R expression restriction to pyramidal or PV neurons was achieved by employing shortened CaMKII and PV promoters, respectively16,17,18,19,20. For simplicity, these two viral constructs will be called the CaMKII and the PV viruses, respectively. We did not perform a comprehensive staining and counting of the CaMKII virus transgenes expressing cells here. However, it has been reported, that this short CaMKII promoter provides strong preference for pyramidal neurons and the exact numbers depend on the species, AAV serotype and titer17,18,19,20. The short PV promoter was designed by our group and a comprehensive staining and counting of the virus transgene expressing cells was reported in a separate paper16. In the paper we show that this PV promoter enables > 98% specificity for interneurons with a strong preference for PV cells: ~66% of transduced neurons are PV-expressing cells16. Here the location of expression of viral transgenes was controlled by observing fluorescence of the virus-delivered eGFP covalently attached to ChR2-H134R (Fig. 2A-D). In the case of the CaMKII virus, most the deep laying neurons had a characteristic apical dendrite directed toward the cortical surface (62 out of 70 eGFP labeled neurons counted in 4 slices from 4 different rats); just below the surface, these dendrites made multiple branches, creating a tuft of small processes (Fig. 2B). A sample staining with the CaMKIIa antibodies confirmed that at least some of these cells were CaMKII-positive pyramidal neurons (Fig. 2D). In contrast, following the PV virus injections, the fluorescent processes of the transduced neurons did not have any clear structure, and none of them reached the surface of the cortex (Fig. 2C). Most fluorescent cell bodies and processes were in the lower two-thirds of the cortex.

Virus injections and recordings were made in the deep layers of the visual cortex area V1. (A) A schematic representation of cortical coronal section containing area V1. (B) A brain section from a rat injected with the CaMKII virus. The gray dashed polygonal line indicates the recording site marked by making a lesion by passing current at the end of the recording session. Note the long fluorescent apical dendrites labeled by virus-delivered GFP; they are shown at higher resolution in the inset on the left, and the white arrowheads indicate these dendrites. (C) A brain section from a rat injected with the PV virus. Note the absence of fluorescent apical dendrites. (D) An example of a neuron labeled with the CaMKII virus that delivered GFP (green) costained with a red fluorescent probe by employing immunohistochemistry for the CaMKIIa antigen. (E) A microphotograph of a tetrode with an optical fiber attached. Abbreviations: SC, superior colliculus; V1, V2, areas V1 and V2; HIPP, hippocampus.

All the recorded single units were divided into putative pyramidal neurons (PPNs) and interneurons (PINs) according to the action potential (AP) width and the time interval between the trough and the peak, as shown in Fig. 321. In the CaMKII virus-injected rats, 77 PPNs and 18 PINs were identified. Although 465 nm light pulses are expected to activate pyramidal neurons in these rats, in most recorded PPNs, LED light pulses suppressed spontaneous AP generation (44/77, 57.1%, 44 ± 13% of control RMS, median 45%; Fig. S1A). The 465 nm light induced APs in ~ 35% of the PPNs (27/77, 35.1%, Fig. S1B). Although these neurons were optically tagged according to standard methods used for detecting neurons directly excited by blue LED light, a detailed analysis revealed that most, if not all, these 27 neurons were synaptically activated (Supplementary material, Fig. S1D). It should be noted that only in 2 out of 18 PINs LED light pulses led to an increase in spontaneous AP generation and they were optically tagged; however, detailed analysis suggests that they were also activated indirectly, i.e., synaptically (Supplementary material, Fig. S1D).

In the PV virus-injected rats, background (spontaneous) AP generation was suppressed in all the PPNs (n = 20, 45 ± 14% of the control RMS, median 40%; Figure S1E). In these rats, only 6 PINs were identified, and spontaneous AP rates were increased in 4 PINs while in 2 PINs there were no significant changes in the spontaneous AP rates (Fig. S1F).

Two types of neurons were distinguished by their action potential shape. The time interval between the trough and the peak is plotted against the trough width in µs. The gray circles correspond to pyramidal neurons, while the black circles correspond to interneurons. The number of circles is lower than the overall number of neurons used for the plot since many points overlap due to the limited resolution of the recordings (25 µs between data points, corresponding to a 40 kHz sampling rate). Representative action potentials of each class of neurons are also shown.

In summary, in the PPNs, the main effect observed was the suppression of the spontaneous AP firing rate in both the CaMKII- and the PV virus-injected rats; i.e., the main effect was inhibitory. The goal of this paper was to investigate the consequences of this inhibitory effect on visual responses, i.e., how the RF area and the SNR of visual responses change during 465 nm LED light stimulation in neurons that do not increase firing rates during LED stimulation. We used slightly different trains of LED light in the CaMKII- and PV virus-injected rats. In the PV virus-injected rats, 50 ms long pulses interleaved with 50 ms pauses were used, while in the CaMKII virus-injected rats, most experiments were performed with 10 or 30 ms pulses interleaved with 90 ms pauses since shorter intervals resulted in too many PPNs being activated by the LED light. On the other hand, a 90 ms interval could not be used in the PV virus-injected rats because of rapid recovery from suppression (τ = 27 ms; Fig. S1H; see Methods for more details). As explained below, no differences in RF area or SNR changes were found between these stimulation protocols, and all the presented data were pooled.

Clearly, in the neurons in which the LED stimulation induced APs, the LED stimulation effects on the RF area and the SNR are likely to be very different. However, we believe that these neurons are largely experimental artifact of our stimulation protocol. Indeed, when the LED pulse duration was 40 ms interleaved with 60 ms pauses, the blue LED light induced APs in 60% of PPNs (12 out of 20, details in the Supplementary Information file). However, when shorter 10 and 30 ms pulses interleaved with 90 ms pauses were used, the blue LED light induced APs in ~ 35% of PPNs (27/78, 34.6%, Supplementary Information). Thus, a decrease in the LED stimulus duration combined with longer pauses reduced the number of the LED light excited neurons by almost half. On the other hand, as shown below, stimulus duration had little effect on the results, suggesting a saturating effect. Thus, it is likely that even very modest activation will produce the effects similar to the ones reported here.

To evaluate visual response changes during 465 nm LED stimulation, we mapped the RF area by flashing 10° wide bright spots (Fig. 4). Although moving gratings or moving bars are typically used to identify RF in cortical visual area V1, we opted for flashed stationary spots for the following reasons. First, the RF area is better determined with spots since 10° wide spots evoke sufficient responses for RF determination, and we were able to determine the ON response RF area in 95 out of 121 identified units (78.5%). Meanwhile, gratings should be much larger, since in rat V1 neurons, the optimal spatial frequency is ~ 0.08 cycles/deg, corresponding to > 10° distance between the peaks of the sinusoidal function in a grating stimulus (Girman et al.., 1999). Flashed bars allow us to determine only the RF width, and additional tests are needed for complete RF mapping11. Second, the use of bright spots allows us to distinguish between ON and OFF responses (in our case, OFF responses are generated by the offset of bright spots rather than the onset of dark spots that are usually used for the OFF response generation). In rodents, the ON and OFF subfields often overlap22,23,24,25, and changes in the RF area of the ON subfield may be compensated for by changes in or the absence of changes in the OFF subfield. Therefore, for analysis, we chose one type of response, the ON response. We did not perform an analysis of OFF responses since the chosen duration of optogenetic stimulation was insufficient to modulate OFF responses (at least for 500 ms following the visual stimulus offset). Another usual argument against RF mapping with small stimuli is that the border areas may generate only subthreshold, undetectable responses to such small stimuli. However, our goal was to determine the ‘effective’ RF area, that is, the RF area in which a modest stimulus produces a suprathreshold response.

Activation of pyramidal neurons reduced the RF area and background noise. The top of the graph shows PSTHs of a single unit obtained during the RF mapping procedure in the CaMKII virus-injected rat. The location of each PSTH represents the location of the visual stimulus on the monitor. For clarity, only a fraction of the PSTHs are shown as indicated by broken line rectangles on the response maps at the bottom of the figure. The gray bars below each PSTH indicate the time when the visual stimulus was presented. In the middle of the figure, the peak responses in the control and during 465 nm LED stimulation are shown. The 465 nm LED stimulation period (a train of 40 ms long pulses at 10 Hz) is indicated by a darker background on the right-hand side of the PSTH. Bottom: a grayscale-coded representation of the responses according to the visual stimulus location on the monitor. Broken line ellipsoids indicate 2D Gaussian fits of the responses. Note the much stronger background response in the control conditions.

Figure 4 shows the results of an RF mapping experiment in a CaMKII virus-injected rat. 10° wide round spots were randomly flashed on a grid with ~ 10° spacing; for clarity, only peristimulus histograms close to the RF area are shown. Trains of 465 nm light strongly suppressed most visual responses except for those in the center of the RF, which are enlarged in the middle of the figure. These results are typical for optogenetic pyramidal neuron stimulation in the CaMKII virus-injected rats. A summary of these results is shown in Fig. 5. In total, 95 single units were identified during recordings obtained from 10 rats injected with the CaMKII virus. In 71 of the units (74.7%), we were able to measure the RF area (in several units, the RF area could not be measured because the RF was located on the border of the monitor). However, 12 out of these 71 units were directly activated by 465 nm light and were excluded from further analysis because of contamination produced by LED-induced APs. Therefore, we could evaluate the effects of optogenetic pyramidal neuron stimulation only in 59 out of 95 neurons (62.1%). The action potential (AP) shape analysis (Fig. 3) revealed that 16 units had narrow APs (27.1%); thus, they were assumed to be putative interneurons (PINs), while the remaining 43 units were putative pyramidal neurons (PPNs) (72.9%).

The RF area was reduced during 465 nm LED stimulation in both CaMKII- and PV virus-injected rats. A and B. Plots of the RF area during 465 nm LED stimulation against the control RF area in pyramidal neurons (A) and interneurons (B) in CaMKII virus-injected rats. Points below the dashed line correspond to a reduction in the RF area, and points above this line correspond to an increase in the RF area. (C) A histogram of the change in the RF area in pyramidal neurons of CaMKII virus-injected rats during 465 nm LED stimulation; values less than 1 correspond to a reduction in the RF area. Note that the x-axis is logarithmic. (D) A plot of the RF area during 465 nm LED stimulation against the control RF area in all neurons in PV virus-injected rats. E. A histogram of the change in the RF area in pyramidal neurons of PV virus-injected rats during 465 nm LED stimulation; values less than 1 correspond to a reduction in the RF area. Note that the x-axis is logarithmic.

In most PPNs, the RF area was reduced (in 40 out of 43 units, 93%, p < 0.0001). In Fig. 5A, changes in the RF area are shown as a scatter plot, in which the RF area during LED stimulation of a unit is plotted against the control RF area of that unit. The dashed line indicates no change in the RF area, and the data points below this line correspond to the RF area reduced during LED stimulation. On average, during LED stimulation, the RF area was 60.1 ± 30.4% of the control area (n = 43, the median 65.1%, p < 0.0001; Fig. 5A and C). There was no difference between the recordings during which 10 ms or 30 ms long 465 nm light pulses were used (54.2 ± 24.4% and 59.4 ± 24.7%, respectively) (n = 22 and 16, p = 0.503; 40 ms long pulses were used for the remaining 5 neurons). There was no correlation between the RF area and the effect size (rs = -0.05, p = 0.75). There was no difference between the effect sizes in the horizontal and vertical directions (72.3 ± 26.7% and 84.2 ± 37.1%, respectively; n = 43; p = 0.114). Changes in the RF area should be the consequence of altered distribution of visual responses across the RF. Therefore, we performed correlation analysis between the LED stimulation induced changes in the RF area and the RF peak and flank response amplitudes (Supplementary figures S2A – B, calculation details are provided in the Supplementary information file). As expected, reduced flank responses correlated with the extent of the RF area reduction (Spearman’s ρ = 0.505, n = 43, p < 0.001, Fig. S2B). In addition, the RF area was more likely to be strongly reduced in units in which the RF peak response was less affected by the LED stimulation (Spearman’s ρ = -0.343, n = 43, p < 0.025, Fig. S2A). On average, in PINs LED stimulation reduced the RF area to 69.1 ± 46.2% of the control area (n = 16, median 54.5%, p = 0.0209; Fig. 5B). The RF area increased in only 2 out of 16 PINs (12.5%). There was no significant difference in optogenetic pyramidal neuron stimulation effects on the RF area between PPNs and PINs (p = 0.976). It should be noted that LED stimulation usually reduces the amplitude of visual responses. To perform comparable experiments, we adjusted the 465 nm LED power such that the average visual response was reduced by ~ 30%. In fact, in the CaMKII virus-injected rats, the peak visual response amplitude (parameter A in Eq. 2 for the 2D Gaussian fit) was reduced during LED stimulation to 79.9 ± 33.5% of the control (n = 59, median value 76%). There was no difference between pyramidal neurons and interneurons: 80.8 ± 33.0% in pyramidal neurons and 77.5 ± 35.8% in interneurons (n = 43 and 16, p = 0.653).

Next, we performed the same experiments in the PV virus-injected rats, 3 rats were used for these control tests. Twenty-six units were identified in these rats; 20 of these units were PPNs (76.9%). On average, during 465 nm LED stimulation, the RF area was 77.5 ± 34% of the control area (n = 20, the median 75.3%, p = 0.0232; Fig. 5D and E). The RF area increased in only 4 out of the 20 PPNs; in the remaining PPNs, the RF area decreased (16 out of 20, 80%). In all 6 neurons with narrow APs, i.e., PINs, the RF area decreased; on average, during 465 nm light stimulation, it was 71 ± 15% of the control (median 76.1%, n = 6, p = 0.05). Moreover, there was no difference in RF area reduction between the PPNs and the PINs (p = 0.9761). Similarly, there was no difference in RF area reduction in PPNs between the CaMKII-injected rats and the PV virus-injected rats (n = 43 and 20, p = 0.0735). Thus, both qualitatively and quantitatively, the effects of 465 nm LED light stimulation on the RF area were very similar in both the CaMKII- and the PV virus-injected rats.

For the SNR measurements, we evaluated noise separately in the absence of a visual stimulus, i.e., spontaneous AP noise, corresponding to the SNRspont, and when a visual stimulus was present outside the RF, the background noise corresponded to the SNRbackgr. In both cases, the signal power was measured as the mean square of the responses to a visual stimulus present in the location for which the average response was maximal. The meaning of both SNR measures will be clarified in an example of a neuronal model.

In PPNs from CaMKII virus-injected rats, LED stimulation increased the SNRspont in 38 out of 43 units (88.4%) and the SNRbackgr in 37 out of 43 units (86.0%). The SNRspont improved on average by 267 ± 355% (n = 43, median 150%, p < 0.0001; Fig. 6A and C), while the SNRbackgr improved on average by 280 ± 423% (n = 43, median 92%, p < 0.0001).

In pyramidal neurons, the spontaneous noise SNR was increased during 465 nm LED stimulation in both CaMKII- and PV virus-injected rats. (A,B) Plots of the SNRspont during 465 nm LED stimulation against control values in pyramidal neurons (A) and interneurons (B) in CaMKII virus-injected rats. Points below the dashed line correspond to a reduction in the SNR, and points above this line correspond to an increase in the SNRspont. (C) A histogram of the change in the SNR during 465 nm LED stimulation in pyramidal neurons of CaMKII-injected rats. Values above 1 correspond to an increase in the SNRspont. Note that the x-axis is logarithmic. (D) A plot of the SNR during 465 nm LED stimulation against the control SNRspont in all neurons in the PV virus-injected rats. (E) A histogram of the change in the SNR in pyramidal neurons of PV virus-injected rats during 465 nm LED stimulation; values above 1 correspond to an increase in the SNRspont. Note that the x-axis is logarithmic. (F – J) is the as (A – E) but for SNRbackgr.

The SNR is defined as the ratio of signal power to noise power, therefore both changes in signal and noise power may contribute to the altered SNR. To estimate which change contributed the most to the LED stimulation effects on SNR, we performed correlation analysis for single units between the LED stimulation induced changes in the noise and the peak response RMS and the SNR changes (Fig. S2D – I). Signal and noise power are simply squared values of the corresponding RMS. This analysis shows that both changes in the signal and the noise RMS contributed to the altered SNRspont (Spearman’s ρ = 0.557, p < 0.0004 and Spearman’s ρ = 0.571, p < 0.0003 respectively, n = 43). Meanwhile, changes in the noise RMS were predominant in the altered SNRbackgr (Spearman’s ρ = 0.791, p < 0.0002 for the noise RMS and Spearman’s ρ = 0.276, p > 0.07 for the peak response RMS, n = 43). In addition, there was a significant correlation between the LED stimulation induced changes in the SNRbackgr and the spontaneous noise RMS (Spearman’s ρ = 0.415, p < 0.006, n = 43) but no significant correlation between changes in the SNRspont and the background noise RMS (Spearman’s ρ = 0.251, p > 0.1, n = 43). To re-phrase, the SNRbackgr correlated with both the background and the spontaneous noise RMS but the SNRspont correlated only with the spontaneous noise RMS. As explained above, the SNRspont was related to both changes in the noise and the signal (the RF peak response) power while changes in the SNRbackgr closely followed only changes in the noise RMS, that is the SNRbackgr was very dependent on the changes in the background noise while the SNRspont less so. Therefore, the consequence of a correlation between the spontaneous and the background noise RMS (Spearman’s ρ = 0.592, p < 0.0003, n = 43) could be felt more in the LED stimulation induced changes of the SNRbackgr than that of the SNRspont. It should be noted that neither changes in the SNRspont, nor changes in the SNRbackgr correlated with the reduced RF flank responses (Spearman’s ρ equal to -0.011 and 0.052 respectively, p > 0.5, n = 43, Figure S2E).

In the PINs, the SNRspont increased in 12 out of 16 PINs (75%, the median 176%, n = 16, p = 0.0574). Meanwhile, the SNRbackgr improved in 11 out of the 13 PINs (84.6%, while in 3 PINs, the SNRbackgr could not be measured), on average by 168 ± 248% (n = 13, median 67%, p = 0.0114; Fig. 6B). There was no statistically significant difference in the SNRspont improvement between 10 ms and 30 ms long 465 nm LED pulse stimulation; the improvement was on average by 279 ± 357% (n = 16, the median 178%) and by 322 ± 372%, respectively (n = 22, the median 165%; p = 0.562 for the difference between 10 ms and 30 ms stimuli). Similarly, no statistically significant difference in SNRbackgr improvement was found between the 10- and 30-ms light pulse stimulation conditions (n = 22 and 16, p = 0.101).

There was a significant correlation between the effects of optogenetic stimulation on the RF area and the SNRspont (rs = -0.33, p = 0.0306, n = 43) but not the SNRbackgr (rs = -0.176, p = 0.257, n = 43), suggesting a common mechanism for RF area reduction and improvement in the SNRspont.

Similar results were obtained for PPNs in PV virus-injected rats: following 465 nm LED stimulation, the SNRspont improved in 18 out of 20 pyramidal neurons (90%), on average by 318 ± 358%, or by a median of 180% (n = 20, p = 0.0008; Fig. 6D and E), while the SNRbackgr improved in 17 out of 20 pyramidal neurons (85%), by a median value of 113% (n = 20, p = 0.0005; Fig. 6D). Moreover, there was no significant difference in the degree to which the SNR improved during LED stimulation in the PPNs between the PV- and CaMKII virus-injected rats (n = 43/43 and 20/20, p = 0.5687 and p = 0.6384 for the SNRbackgr and SNRbackgr, respectively). Notably, in the few PINs of the PV-injected rats, there was no reduction in normalized noise (25 ± 76% on average, n = 6). This result can be explained by the fact that 4 out of the 6 of these PINs were apparently stimulated by 465 nm light (supplementary figure S1F). Apparently, direct stimulation by 465 nm light compensated for the inhibitory effect.

A response map (see Fig. 4 for a more detailed explanation) was generated by an integrate-and-fire neuron with a 6-unit input. Shades of gray represent the probability of AP generation during visual stimulus presentation in the corresponding location of the monitor.

To demonstrate that the observed change in SNR can be utilized by real neurons, we constructed a simple integrate-and-fire neuron that was fed in with an input of real units. We chose 6 units from the same recording session of the PV virus-injected rat that had highly overlapping receptive fields. In these units, the SNRspont improved by 180 ± 151% (median 129%), while the SNRbackgr improved by 734 ± 361% (median 790%). The threshold for output was reached only when at least two APs arrived at < 10 ms. As expected, during LED stimulation, the RF of this model neuron became sharper (Fig. 7). Importantly, there was an increased association between the presence of APs and a visual stimulus in the RF: 37 out of 353 APs (10.5%) in the control group and 28 out of 117 APs (23.9%) during LED stimulation were generated when a visual stimulus was present in the RF, a > 2-fold increase in such an association. Such an increase in the association or dependence of one variable on another is equivalent to an increase in mutual information. Therefore, we calculated the mutual information between the AP events and the presence of a visual stimulus in the RF. To this end, we divided the simulated neuron output into 0.1 s bins, which were considered positive if at least 1 output AP was present while the remaining bins were considered negative. The total numbers of control and stimulation segments were the same. Notably, if a visual stimulus was present outside the RF, then these APs contributed to the SNRbackgr estimate; if no visual stimulus was present, then these APs contributed to the SNRspont. Thus, both types of noise are important. In our model, under control conditions, the mutual information between APs and the presence of a visual stimulus inside the RF was 0.0038 bits, while during LED stimulation, it was 0.0049 bits, a 29% improvement. Under ideal conditions, i.e., if APs were generated only when a visual stimulus was present inside the RF, the mutual information would equal 0.088 bits. Such a low mutual information value is explained by the experimental procedure used for RF mapping: a visual stimulus was presented multiple times outside the RF, which yielded little information about the stimulus. Thus, our model neuron possessed ~ 5% of the maximal possible information about the visual stimulus. Although it is a single example, it shows a clear relationship between the improved SNRspont and SNRbackgr and the enhanced information encoded by APs about visual stimulus.

Discussion

We demonstrated that in the rat area, V1 optogenetic stimulation of pyramidal layer IV–VI neurons or PV interneurons enhances the visual information encoded by nearby pyramidal neurons. In these neurons, the RF area is reduced; thus, the location of the visual stimulus can be pinpointed more accurately, and the SNR is increased; thus, the presence of a visual stimulus in the RF can be detected with fewer errors. A simple integrate-and-fire model neuron demonstrated that optogenetic stimulation of interneurons led to an increase in the mutual information of AP trains and the visual stimulus. Although it has been shown previously that V1 interneuron stimulation may enhance visual information due to increased selectivity and response reliability, to the best of our knowledge, we are the first to report changes in the SNR and an increase in the amount of information encoded by APs during optogenetic interneuron stimulation in V1. Importantly, we demonstrated that pyramidal neuron stimulation alone is sufficient to enhance the visual information encoded by nearby pyramidal neurons. To date, only changes in visual response gain have been reported during optogenetic stimulation of pyramidal neurons in V1.

It should be noted that all results reported here relate only to these neurons, in which mainly the inhibitory effect during LED stimulation was observed (~ 65% of all neurons). In the remaining ~ 35% of neurons LED stimulation induced APs that are likely to interfere with the visual signal. However, we believe that to a large extent these neurons are an experimental artifact. This belief is supported by two observations. First, the reported effects did not depend on the LED stimulus duration. Second, a reduction in the stimulus duration accompanied by increased pause between the LED light pulses reduced the number of such LED activated neurons from ~ 60% to ~35%. Our intent was to simulate neuronal activation during visual stimulus presentation or during awake state that is likely to be less synchronized, this should further reduce the number of strongly activated neurons. In short, we believe that under real conditions most neurons will behave as the ones used for this study.

To evaluate the results, we must examine the network activity induced by optogenetic stimulation. The expression of light-sensitive ChR2-H134R channels restricted to either pyramidal neurons or PV interneurons was achieved using AAV constructs with short promoters. It is known that these short promoters often do not provide 100% specificity18,20,26. For ChR2-H134R expression in inhibitory interneurons, we used a short PV promoter. The specificity of this PV virus in rats was comprehensively evaluated by our group and the results were reported in a separate paper16, in that study we have shown that the PV virus delivered eGFP was found almost exclusively in interneurons (> 98%) with strong preference for PV interneurons (~ 2/3ds of eGFP + cells)16. This specificity for inhibitory interneurons was confirmed by single-unit data: 465 nm LED light activated only PINs, while in all PPNs, spontaneous APs were suppressed. Moreover, the rapid recovery from this suppression, τ = 27 ms, is very close to the estimated closing τ of ChR2-H134R channels27. This rapid recovery is consistent with the hypothesis that in PV virus-injected rats, widespread inhibition was induced by direct activation of inhibitory interneurons, mainly the PV type, by LED light, and as the LED light was turned off, ChR2-H134R channel closure determined the kinetics of recovery from this inhibition.

For ChR2-H134R channel expression in pyramidal neurons, we used a standard short CaMKII promoter that in most cases provides a strong transcriptional bias towards excitatory neurons that depends on animal species, AAV serotype and titer17,18,19,20. For this viral construct, we did not perform a comprehensive staining and counting, we only noted that most of the virus delivered eGFP was expressed in cells that had a characteristic pyramidal shape with an apical dendrite extending to the cortical surface and at least some of them were labeled with CaMKII antibody. This eGFP staining pattern differed dramatically from the one observed in the PV virus injected rats (Fig. 2). Physiological evidence supports the hypothesis that in CaMKII virus-injected rats, pyramidal neuron activation is the main network driving force during optogenetic stimulation: 465 nm LED light activates 35.1% of PPNs and only 2 out of 18 PINs (11.1%). However, in the remaining ~ 2/3ds of PPNs, spontaneous APs were suppressed. Moreover, the suppression of spontaneous APs could be detected even in neurons that were activated during 465 nm light pulses (Supplementary figure S1B, arrows). Such a pattern of network activity, brief excitation followed by ~ 100 ms of inhibition, is observed during microstimulation of the cortex; it has been shown that inhibition is responsible for such suppression of spontaneous APs28.

Thus, it is unclear which neurons produce this inhibition in the CaMKII virus injected rats, since, during LED stimulation, firing rates increase in only 2 out of 18 PINs. Here, we list 3 possible explanations.

First, since the light source was relatively far from the recording electrode (> 300 μm), and in the brain tissue, the light intensity drops off very quickly within ~ 100 μm29, it is likely that the source of excitation and inhibition was very compact, < 100 μm wide, and quite far from the recording electrode (~ 300 μm). At this distance, only the MU signal can be recorded, no single units30. It is likely that these active interneurons inside this distant excitation source were undetected as single units and may have contributed to the MU signal.

The second potential reason may be that even a low number of active interneurons or/and low activity of these interneurons is sufficient to significantly suppress spontaneous activity. Area V1 can function as an ISN2; in such networks, inhibition must be sufficiently strong to prevent the run-off of uncontrolled excitation3, and even activation of ~ 10% of PV cells is sufficient to affect network dynamics31.

Third, only single units with narrow APs were identified as interneurons. However, some somatostatin interneurons generate wide APs, similar to pyramidal neuron-generated APs32,33. It is possible that several PPNs, which are slowly activated by LED light, are actually somatostatin interneurons that are responsible for widespread inhibition during LED stimulation.

To summarize, in the CaMKII virus-injected rats, optogenetic stimulation first activated a set of pyramidal neurons close to the tip of the optical fiber, which in turn activated a low number of nearby interneurons, producing the observed widespread inhibitory effect. Microstimulation studies indicate that this effect can spread > 1000 μm in length28. Since we estimated the LED light effects only in neurons not activated by the LED light in the CaMKII virus-injected rats, we investigated the consequences of this widespread inhibitory effect. Therefore, the absence of a difference between the results obtained in the PV and the CaMKII virus-injected rats was expected.

We can exclude the possibility that some non-specific effects of LED light on tissue or GFP expressing cells produced the observed inhibitory effect since in control experiments, with sham virus injections and with rats injected with a virus producing eGFP expressing cells without any light sensitive channels, no effects on neuronal activity of LED light were observed, even at maximal power.

It has been shown that stimulation of area V1 interneurons improves orientation selectivity and reliability of visual responses6,7,8,9,34. These two effects are likely to enhance visual information in area V1: higher selectivity should provide more precise or simply more information about orientation, and more reliable responses are likely to result in fewer errors in stimulus detection. Thus, early reports that suggested an increase in the RF area following PV interneuron stimulation24,35 seemed at odds with these results: an increase in the RF area should degrade visual information since the location of the visual stimulus would be determined less accurately. It is possible that the methods used to determine the RF area were responsible for these results. In both studies, round gratings of different sizes were used to determine the grating size required to induce the maximal response; this ‘optimal’ size was considered to correspond to the RF size24,35. However, the optimal grating size depends on both the classical RF area and the nonclassical suppressive surround. Since the suppressive surround may depend on the activation of SOM interneurons36, which can directly inactivate PV interneurons9, it is possible that PV interneuron activation or inhibition disrupts the area in which V1 circuits affect the suppressive nonclassical surround, obscuring the real effect of PV neuron activation on the classical RF size. In contrast, in a recent study that revealed a decrease in RF width following PV interneuron stimulation, stationary bars were used to map the RF width in the horizontal direction11. To map the RF area, we used stationary flashed spots. This method has been criticized for insufficient sensitivity in the fringe RF area and because the moving bars are thought to be a more selective and effective stimulus for area V1 neurons. To increase sensitivity, we used large, 10° wide spots; consequently, most neurons generated detectable visual responses ( > ~ 75% of all neurons). We may have excluded some neurons that are sensitive to moving stimuli only, but these neurons are clearly in the minority. The use of large stimuli may have created bias in the measured RF area; indeed, we did not find RF areas smaller than 90°, which roughly corresponded to our stimulus size. However, we were able to observe a reduction in the RF area during LED stimulation. In addition, similar RF areas were reported by other investigators for the rat visual cortex22,37,38.

Our experiments were performed in deep cortical layers IV–VI; therefore, our results can be compared with the work performed in the NTSR1-Cre mouse line, a line that targets a subpopulation of layer VI pyramidal neurons13,39. These experiments showed that activation of this subpopulation of layer VI pyramidal cells strongly suppressed visual responses. However, no changes in direction or orientation selectivity were detected while neither the SNR nor the RF area was measured. Interestingly, stimulation of the same layer VI neurons induced a reduction in the RF area in some lateral geniculate neurons (LGN)40,41. The LGN is a visual center with reciprocal connections with the deep layers of the visual cortex; it is possible that these findings are related to our findings.

The improvement in the SNR following inhibitory network stimulation is, to the best of our knowledge, an entirely new result. The SNR improved ~ 4-fold, which can result in fewer errors in stimulus detection. Indeed, our example of a simple integrate-and-fire neuron model shows that such an improvement in the SNR may enable a neuron to transfer/encode more information about the presence of a visual stimulus in a particular location. All our experiments were performed at a single contrast, only high contrast bright spots on a dark background were used. The observed improvement in the SNR is due to stronger suppression by optogenetic stimulation of noise compared to visual responses. The noise power was several folds lower than the power of visual responses (see SNR distribution in Fig. 6); therefore, it is plausible that weak responses to low contrast spots will be suppressed more than responses to high contrast spots. In other words, the observed improvement in the SNR maybe limited to responses to high contrast visual stimuli as it has been shown in behavioral experiments with gratings in mice, when activation of PV interneurons actually degraded visual perception of low contrast images42,43. It is plausible that the ‘iceberg’ effect can explain our results as it was suggested for changes in the RF width11, but this can be proven only with intracellular recordings. The data presented here are only in part consistent with the ‘iceberg’ effect: although there was correlation between the LED stimulation induced changes in the SNR and noise RMS (Fig. S2F and H), only changes in the SNRspont correlated with the peak response amplitude and no correlation was found between the reduction in the flank response amplitude and SNR changes (Fig. S2E). Meanwhile, changes in the RF area did correlate with the reduced flank responses (Fig. S2B). Furthemore, the SNR was improved for a very large range of control SNR values, from ~ 2 to ~ 100 (Fig. 6A), thus, even though experiments were performed at a single contrast, the obtained data does not support the notion that optogenetic stimulation will improve the SNR only for visual responses with a high control SNR. All these observations suggest that neither the ‘iceberg’ effect, nor spatially non-uniform changes in synaptic inputs (the RF flanks versus the RF center) can explain all observed effects; it is likely that multiple mechanisms are involved. Further research is needed to address all these questions.

All our experiments were performed on anesthetized animals. It is known that anesthesia does affect visual response properties and spontaneous activity, noise24,44,45. However, most differences are quantitative and, compared to other methods, urethane anesthesia induces fewer changes in the visual response properties. The analysis presented in this Discussion indicates that our results are explained by the fact that a brief activation of excitatory neurons leads to suppression of neighboring cells by inhibitory neurons, that is by the inhibitory feedback circuitry. It is known that such inhibition is induced also in awake animals, including primates9,46. Tests in awake animals and simulations show that a period of high activity of excitatory neurons is followed by a period of suppressed activity, this occurs both in anesthetized animals as it is shown here and in awake animals as it is shown by multiple studies47,48. Therefore, it is likely that the effects of local, brief stimulation of excitatory neurons on the RF area and the SNR reported here could be observed also in awake animals with some quantitative differences, probably, responses will be stronger and faster since neurons are in a higher conductance state.

Conclusion

We demonstrated that, in the deep layers of V1, local stimulation of pyramidal neurons produces an effect very similar to that of PV interneuron stimulation: an increase in the SNR and a decrease in the RF area. These two effects improve the visual information encoded by local pyramidal neurons: the location of the visual stimulus can be pinpointed more accurately because of the reduced RF area, and a visual stimulus can be detected with fewer errors due to increased SNR.

We conclude that any increase in local activity in the deep layers of area V1 neurons, either due to sensory inputs or to a state of wakefulness, may result in improved visual information processing.

Methods

In vivo injection of viral particles

All procedures were carried out in accordance with the European Communities Council Directive of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes (2010/63/EEC) and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the State Food and Veterinary Service of Lithuania (No. G2-147 of May 13, 2020). All methods involving animals were carried out in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines49,50,51. In this type of research, there was no control group of animals because we compared the 465 nm LED on and off effects in the same animal. No 465 nm LED effects were ever observed in noninjected animals or in animals in which sham virus injections were performed, i.e., all surgical procedure for virus injections but a phosphate buffered saline without a virus was injected.

Two virus constructs were used

For channelrhodopsin expression in PV interneurons, an AAV construct with a short PV promoter designed by our group was used16. Viral particles were purchased from Virovek (Houston, TX 77070, USA), and the stated concentration was 2 × 10^13 vg/mL. For channelrhodopsin expression mostly in pyramidal neurons, the short PV promoter was substituted for the short CaMKII promoter (Dittgen et al.., 2004) in the same construct, and the promoter sequence was obtained by subcloning the plasmid pAAV-CaMKIIa-mCherry, which was a gift from Karl Deisseroth (Addgene plasmid #114469; http://n2t.net/addgene:114469; RRID: Addgene_114469). In addition, the Pv poly(A) sequence was substituted with a standard hHG poly(A) signal. Viral particles were purchased from Creative Biogene (Shirley, NY 11967, USA), and the stated concentration was 10^13 vg/mL.

Standard procedures were used for virus injections

Briefly, 18 Wistar rats of both sexes, weighing 180 to 450 g (1.5–4 months old), were anesthetized with a mixture of xylazine chloride (Eurovet Animal Health B.V., Bladel, Netherlands, 10 mg kg-1), ketamine (Richter Pharma AG, Wels, Austria, 60 mg kg-1) and butorphanol (Richter Pharma AG, Wels, Austria, 0.4 mg kg-1), which were delivered intraperitoneally. The depth of anesthesia was monitored by testing for the absence of a hind limb withdrawal reflex following a pinch of the paw. To maintain the depth of anesthesia, additional doses of the mixture were used as needed for the duration of the experiment. Under anesthesia, the body temperature was maintained at 36–38 °C with a heating pad. The anesthetized animal was placed in a stereotaxic apparatus (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA). A small craniotomy (approximately 1 × 1 mm) was made in the parietal bone immediately above the visual cortex areas V1/V2 (the injection coordinates were 1–2 mm rostral to the lambda and 2–3 mm lateral to the midline). To facilitate glass pipette penetration, a small cut of the dura mater was made. Before injection, the virus particles (10^13 particles/mL) were mixed with a warm phosphate buffer solution (ratio 1:1) and 0. 8 µL of the mixture was used for injections, corresponding to a total of 4 * 10^9 (CaMKII virus) or 8 * 10^9 (PV virus) injected viral particles. Injections were performed with a pipette made from a borosilicate glass capillary and attached to a 10 µL Hamilton syringe (CH-7402 Bonaduz, GR, Switzerland); the pipette tip size was 30–40 μm. The injection depth was between 700 μm and 1200 μm. Following pipette withdrawal, the scar was cleaned, the scalp was closed with sutures, and prophylactic antibiotics were given.

Following the injection, the rats were returned to their home cages. Care was taken to avoid any infections. Recordings were performed 27 to 44 days post-injection. The time post-injection affects the expression level of transduced cells, and after the initial increase, the expression usually plateaus after 4 to 6 weeks52. No correlation was found between the age or sex of the rats. Therefore, data from all rats of different ages and sexes were pooled.

Extracellular recording procedures

All procedures were carried out in accordance with the European Communities Council Directive of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes (2010/63/EEC) and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the State Food and Veterinary Service of Lithuania (No. G2-147 of May 13, 2020).

Wistar rats were used in this study. Although Wistar rats are albino and, compared to those of pigmented rats, their visual acuity is approximately twofold lower53, the receptive field sizes are similar to those reported for pigmented rats22,37,38. In addition, albino rats exhibit greater sensitivity to dim stimuli, and visual responses of the superior colliculus neurons are largely the same in both pigmented and albino rats54,55. We are not aware of a similar comparison of neuronal responses in the visual cortex.

Standard procedures were used for single-unit recordings56,57. Briefly, rats were anesthetized with urethane (Alfa Aesar – Thermo Fisher, Karlsruhe, Germany; 1.2–1.7 g kg− 1) aided with butorphanol (Richter Pharma AG, Wels, Austria; 0.4 g kg− 1), both of which were delivered intraperitoneally58. The depth of anesthesia was monitored by testing for the absence of a hind limb withdrawal reflex following a pinch of the paw. To maintain the depth of anesthesia, additional doses of butorphanol were used as needed for the duration of the experiment. Under anesthesia, the body temperature was maintained at 36–38 °C with a heating pad. The anesthetized animal was placed in a modified stereotaxic apparatus (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA) that enabled an unobstructed view of the left eye. Eye gel (Artelac Nighttime Gel, Baush & Lomb Incorporated, Berlin, Germany) was applied to avoid eye drying. Although eye movements are rarely problematic in anesthetized rats59, to prevent eye movements and maintain lid opening, miniature hooks were inserted between the conjunctiva of the inner eyelids and the sclera and then attached to the stereotaxic frame with a thread. Preliminary experiments showed that such hooks completely eliminated occasional drifts in the receptive field position that were sometimes observed without hooks; differences in response amplitude to stimuli at centers as little as 1 degree apart could be detected57. To dilate the pupils, 0.5% atropine (Sigma‒Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Taufkirchen, Germany) was applied to the cornea surface. Eye dilation increases light scattering, which may confound the measurements of the receptive field size. However, pupil dilation or systemic atropine or D-turbocurarine, which both also result in pupil dilation, are often applied during such experiments, allowing us to compare our data with those of other studies straightforwardly22,23,38,60,61.

For recording, a small craniotomy (approximately 2 × 2 mm) was made in the parietal bone, and a small incision was made in the dura mater. Tetrodes from Thomas Recording (Giessen, Germany) were used to acquire action potential data, while a blue PlexBright LED of 465 nm (Plexon, Dallas, Texas, USA) was used to excite neurons expressing channelrhodopsins. The LED light was delivered via a 105 μm optic fiber (Thorlabs GmbH, Munich, Germany) glued to the tetrode such that the fiber tip was located > ~ 300 μm above the tetrode tip (maximal nominal power at the tip ~ 5mW, the measured maximal irradiance 130mW/mm2 at the fiber tip; the actual power was adjusted as described in the “Results” section). Since the optical fiber was relatively far away from the tetrode tip with an exposed metal surface and the surrounding tissue dissipated most of the laser light before it reached this exposed metal surface, no optoelectrical artifacts were noted in control recordings with no virus injections or in the rats injected with a virus containing an eGFP transgene but no ChR2. Electrodes were typically placed 1.5–2.5 mm rostral to lambda and 2.5–3.5 mm lateral to the midline and then lowered perpendicular to the cortical surface by means of a microdrive to a depth of > ~ 1000 μm. In 10 rats, we generated lesions by passing a 5–15 µA current through the recording electrode at the end of the experiment (Fig. 1). All these lesion experiments confirmed that deep layers of the cortex were recorded (~ layers IV-VI).

For data acquisition, a 4-channel differential amplifier was used (EX4-400, DAGAN, Minneapolis, MN, USA) with bandpass filters set to 300 − 10,000 Hz. The data were acquired via a National Instrument DAQ card PCI-MIO-16E-1 (6070E) connected to a PC at a 40 kHz sampling frequency and visualized by employing a custom program written in the LabVIEW environment (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA). Although the sampling rate of 40 kHz in theory is excessive, tests have shown that this approach improves the signal-to-noise ratio, presumably because the real signal has very high frequency components that are not completely cancelled out by the analogous filters of the amplifier.

Visual stimulation

An LED backlit LCD monitor (frame rate 60 Hz, 58 cm by 28 cm) was used for image presentation and was placed 16 cm from the right eye. The bottom of the monitor was slightly (~ 5 cm) below the rat eye level. The monitor was inclined at a 45° angle to the rat’s longitudinal axis in the horizontal plane. In the vertical plane, the monitor was inclined at 30 degrees toward the rat to cover a wider range of vertical angles. The full screen subtended 110 horizontally and approximately 80 degrees vertically. At the center of the screen, 1 cm corresponded to ~ 3.6° of the visual angle. During the experiments, the stimulus size was entered as a fraction of the monitor height; 1/10th of the monitor height was considered to correspond to 10° of the visual angle (actual calculations show that it is 2.8 cm * 3.4 deg/cm = 10.08 deg). Rat eyes are normally emmetropic and can see sufficiently well from 7 cm to infinity62. Apparently, rat vision is mainly used to discern large predators63 and has low acuity even for short distances64. The monitor had 1920 × 1080 image pixels or > 30 pixels/cm corresponding to a minimal stimulus size of < 0.1°, which is well below the visual acuity of ~ 0.5°–1° found in rodents64. Images were generated by employing the open-source software package PsychoPy, which is controlled by an in-house program written in Python and synchronized with recordings via the LabVIEW environment (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA).

All the visual stimuli used were bright images (~ 30–45 cd/m2 at the rat’s eye level) presented on a dark gray background (~ 0.3–0.45 cd/m2).

The following visual stimulation protocol was used. The receptive field size and location were determined by flashing 10.0° wide bright round spots for 600 ms followed by a 1900 ms gap (2.5 s interstimulus interval, ISI) on an 18 × 11 grid in a quasi random fashion; in some cases, smaller grids were used. Usually, the grid spacing was ~ 10°; however, for smaller receptive field sizes, a 7°-8° spacing was used. Clearly, the use of such a large stimulus of 10.0° was chosen to enable distinguishable visual responses, but the disadvantage was that the minimal estimated RF size was approximately 10.0° wide. However, in rats, receptive fields are rarely less than 10.0° in diameter22,38; moreover, we observed a reduction in the receptive field area upon 465 nm LED stimulation; thus, if the actual size of the reduced receptive field was < 10.0°, our data underestimate only the 465 nm LED stimulation effects. Each grid location was tested 5 to 10 times. Following a preliminary estimate of the receptive field location and size, 465 nm LED stimulation (Plexon LED module driven by PlexBright LD-1, Plexon, Dallas, Texas, USA) was applied during visual stimulus presentation in a quasi random fashion during the same run as the control visual stimulus presentations.

465-nm LED stimulation

The 465 nm LED was controlled by the analog signal generated by LabView software and fed into the PlexBright LD-1 analog control input. Typically, the 465 nm LED stimulus started 100–250 ms before visual stimulus onset and lasted for 500–800 ms; however, for spontaneous noise measurements the LED stimulation started at least 500 ms before the visual stimulus onset and lasted ~ 1000 ms. Due to differences in the kinetics of recovery from LED stimulation, we used slightly different trains of light pulses in the PV- and CaMKII virus-injected rats. The recovery from the suppression of the AP firing rate was much slower in the CaMKII virus-injected rats than in the control rats: the average recovery time constant was 27 ± 2.2 ms in the PV virus-injected rats and 85 ± 7 ms in the CaMKII virus-injected rats (n = 20 and 47, respectively; p < 0.001; Supplementary material, Fig. S1H). Therefore, in the PV-injected rats, trains of 50 ms long pulses were interleaved with a 50 ms pause, and 7 or 9 such pulses were used. In CaMKII virus-injected rats, a similar stimulation protocol (40 ms pulses interleaved with a 50 ms pause) resulted in a very high percentage of PPNs activated by light pulses (up to 80%), severely limiting the analysis of visual responses. Therefore, in the CamKII virus-injected rats, we mostly used 10 ms long 465 nm LED pulses delivered every 100 ms, while in two rats, 30 ms pulses delivered each 120 ms were used; in both cases, there was a 90 ms pause between light pulses. The data analysis showed that these stimulation protocols induced similar effects on the RF area and SNR (see the “Results” section); therefore, the presented data were pooled for all three stimulation protocols. No effect of 465-nm LED stimulation was found in the rats injected with a virus carrying a fluorescence protein but no channelrhodopsin transgene (either a virus with the eGFP transgene under short PV promoter16 or a virus with the mCherry transgene under short CaMKIIa promoter (a gift from Karl Deisseroth, Addgene viral prep # 114469-AAV5 ; http://n2t.net/addgene:114469 ; RRID: Addgene_114469).

Spike detection and sorting

Most analyses of recorded traces were performed with custom written routines by employing Igor Pro software (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, Oregon, USA). MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) was used for principal component analysis (PCA), while data clustering analysis was performed with the publicly available KlustaKwik software (http://klustakwik.sourceforge.net).

Spike detection and sorting

Single units were first detected as threshold-crossing events, while the threshold was set from 3 to 4.5 standard deviations from the baseline. The standard deviation was calculated according to Quiroga et al.65. The threshold was lowered by 30% when synchronous events occurred on 2 or more traces. Care was taken that no artifacts were present in the trace. For each detected event between 1.1 ms and 1.6 ms of each channel data were collected, 44–62 data points in total: 14–20 before and 30–45 after the negative peak. The window duration was determined by the shape of the action potentials. For spike sorting, each channel’s data were reduced by principal component analysis (PCA) via MATLAB software. Then, spike classes were determined by finding clusters of 2–5 PCAs from each channel by employing KlustaKwik software (http://klustakwik.sourceforge.net). The quality of sorting was verified by the occurrence of a refractory period with auto and cross-correlograms66.

Data analysis

To identify optically tagged neurons, we used a stimulus-associated spike latency test (Kvitsiani et al., 2013). In this test, the distribution of first-spike latencies relative to the start of the 465 nm LED light pulse was compared to the latency distributions obtained in the stimulus-free baseline period when neither 465 nm LED light was on nor when a visual stimulus was presented; 500 such randomly picked up distributions were used for each test. We chose a 50 ms window for latency detection. To measure differences between distributions, a modified Jensen–Shannon divergence measure D2JSm was used:

,

where pi and qi are the probabilities of the N possible values of the discrete distributions P and Q, respectively. A neuron was considered to be optically tagged if the probability of Jensen–Shannon divergence between the 465 nm LED-induced and a randomly selected latency distribution was < 0.01, as assessed by the distribution of divergences between randomly selected baseline distributions.

A response to a visual stimulus was considered to be present/detectable if the frequency of action potentials during visual stimulus presentation exceeded the background firing frequency by > 3 standard deviations of the background noise. The background firing rate and standard deviation were calculated for a 1 s time interval before visual stimulus presentation, and 100 ms binning was applied during these calculations.

The average spike rates during visual stimulus presentation were calculated for each location of the stimulus. Then, a two-dimensional Gaussian function was used to fit the spatial distribution of these spike rate values23:

,

where x’ and y’ are the polar transformations of space coordinates x and y, respectively, along which the Gaussian distribution is oriented; a and b are standard deviations of the Gaussian function in the direction of the x’ and y’ axes, respectively; and A is the predicted maximal spike rate in the RF center. The RF area was calculated as π\(\:*\)a\(\:*\)b (the ellipse area with semiaxes a and b).

Two types of signal-to-noise ratio calculations were used that differed in noise definition. In both cases, the signal power was assessed as the mean square of individual action potential numbers during visual stimulus presentation, that is, the mean square of all responses during visual stimulus presentation in a location inducing a maximum visual response. The number of such presentations varied between 5 and 16. If the average number of action potentials during visual response differed by less than 20% for two different locations, then the response to visual stimulus presentation in both locations was used to calculate the signal power. We considered two types of noise. First, spontaneous activity noise was presented when no visual stimulus was presented. In this case, at least 300 brief sections of ~ 0.5 s of spontaneous activity just before visual stimulus presentation were used for calculations. An interval length of 0.5 s was chosen to correspond to the duration of the visual responses. In the “Results” section, this type of noise is called spontaneous noise. Second, noise power was also evaluated during visual stimulus presentations outside the RF (beyond 0.1*A isoline of the Gaussian fit); at least 20 locations outside the RF were used; since the visual stimulus was presented at least 5 times at each location, the total number of data points used for noise power calculations was > 100, typically ~ 300–500 points. This type of noise is called ‘RF background noise’.

To assess the mutual information between the action potentials of an artificial neuron and the visual stimulus, we used a two-step procedure. First, we used a simple integrated fire model of a neuron to generate action potentials:

,

where \(\:{\tau\:}_{m}\) is the membrane constant, EL is the resting potential (assumed to be equal to 0), V is the current membrane potential, Ie is the total current and Rm is the membrane resistance. The membrane constant was assumed to be equal to 10 ms. It was assumed that all action potentials generated an instantaneous synaptic current of total charge equal to 1 and that action potential generation was followed by a decrease in the membrane voltage by 1. The action potential generation threshold was set to 1.8. Inputs were generated by combining 6 units of one recording session that responded to a visual stimulus and were not optically tagged by 465 nm LED stimulation. Next, it was assumed that each action potential generated by this artificial neuron signaled the presence of a visual stimulus in the receptive field. Therefore, we calculated the mutual information of these action potentials and the presence of visual stimuli in the receptive field. To this end, the whole sequence of artificial action potentials was binned into 0.1 s long intervals. For each such bin, two values were assigned: if at least one action potential was generated (an action potential was present) and if a visual stimulus was present in the receptive field. Then, mutual information between these two variables, I(AP; Stim), was calculated:

,

where P(AP, Stim) is the joint probability of the presence of an AP and a visual stimulus in the receptive field (in both cases, only two values were assumed to be possible, present or not), while PAP and PStim are marginal probabilities of the presence of an action potential and visual stimulus in the receptive field, respectively.

Tissue sectioning

Following carbon dioxide euthanasia, thoracotomy was performed, and then an incision was made in the right atrium, followed by ample perfusion of the hearts in situ with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) via a syringe needle inserted into the left ventricle67. Blood was washed from the vessels, and the heart was controlled visually. Then, the prefixation with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution in PBS was applied. The composition of the PBS mixture was as follows (in mM): 137 NaCl, 2.7 KCl, 10 Na2HPO4, and 2 KH2PO4. The brain was exposed and extirpated under a dissecting microscope (Stemi 2000; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). The extracted whole brain was sliced at the coronal plane using an acrylic adult rat brain slicer (Zivic Instruments, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), and several thick (~ 2 mm) slices at the level of the occipital lobes were used for fixation for 3 h in 4% PFA in PBS. Then, the slices were washed 3 × 10 min in PBS, cryoprotected by immersion in PBS containing 30% sucrose and 0.05% sodium azide at 4 °C for 24 h and frozen while embedded in tissue-freezing medium (Triangle Biomedical Sciences, USA) using liquid nitrogen. Fifty-micron serial sections of the cortex were prepared from the aforementioned slices employing a CryoStar NX70 cryomicrotome (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The sections were immersed in PBS containing 0.05% sodium azide and left at 4 °C until immunohistochemical staining of the free floating sections was performed.

Immunohistochemistry

Prior to incubation with antibodies, all brain sections were left for 50 min in solution containing 1 part DMSO and 10 parts PBS with 1% Triton X-100. Next, the sections were rinsed three times for 10 min in pure PBS solution. Nonspecific binding sites in the tissue were blocked by incubation in 5% normal donkey serum in PBS for 1 h. After washing in PBS 3 × 10 min, the sections were soaked in microchambers with a solution of primary antibody at a 1:500 dilution (CaMKII, MA1-048; Invitrogen, USA). The sections were left in a refrigerator at 4 °C overnight. Then, the sections were rinsed in PBS 3 × 10 min, and secondary antibodies (Mouse-AF555, A32773, Invitrogen, USA) were applied for at least 2 h. Finally, the specimens were again rinsed in PBS 3 × 10 min. Both the primary and the secondary antibodies were diluted in the Antibody Diluent ab64211 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Afterwards, the free-floating cortical sections were carefully transferred on microscope slides. All preparations were cover-slipped using mounting medium (Vectashield, Vector Laboratories, USA) and sealed with clear nail polish.

Microscopy and image analysis

Images were acquired employing either a laser-scanning microscope LSM 700 with ZEN Black SP1 2010B software (version 6.0.0.485) using 20×/0.8 Plan Apochromat, 40×/1.4 Plan Apochromat and 60×/1.46 αPlan Apochromat oil immersion objectives (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) or a fluorescence microscope AxioImager Z1 equipped with a 20×/0.5 Pol EC Plan-Neofluar objective and a digital camera AxioCamMRm running Zeiss AxioVision software (rel. 4.8.2; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Image analysis was performed with the freely available ImageJ software, version Java 1.8.0_172 (64 bit). Two-channel nonprojected Z-stack images were used for the measurements. Microphotographs for the figures were generated by adjusting the image size, brightness and contrast using Adobe Illustrator (Adobe Systems, San Jose, USA), and the same adjustments were made prior to quantification. Brain structures were identified according to a stereotaxic atlas of the rat brain68.

Experimental design and statistical analyses

Unless stated otherwise, all the results are presented as the average ± SD plus the median for nonnormally distributed data. Most of the data presented here are from repeated measurements or matched pairs (465 nm LED on/465 nm LED off). The Shapiro‒Wilk test of normality showed significant deviation from a normal distribution for a few data sets. Therefore, a nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-ranks 2-tailed test was used for matched pairs. For independent samples, a nonparametric Kruskal‒Walli’s 2-tailed test for a fixed-effects model was used. For multiple comparisons during the recovery of firing rates from 465 nm LED-induced suppression, Dunn–Sidak correction was employed. In the figures, the population data are presented as box plots (Q1, Q2, and Q3; whiskers indicate the 10 − 90% range).

Data availability

The author declares that all the data necessary for evaluation of the statements of this paper are present in the manuscript. However, any additional reasonable requests for data will be granted by the corresponding author.

References

Douglas, R. J. & Martin, K. A. Recurrent neuronal circuits in the neocortex. Curr. Biol. 17, R496–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2007.04.024 (2007).

Sanzeni, A. et al. Inhibition stabilization is a widespread property of cortical networks. Elife. 9https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.54875 (2020).

Sadeh, S. & Clopath, C. Inhibitory stabilization and cortical computation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 22, 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-020-00390-z (2021).

Ozeki, H., Finn, I. M., Schaffer, E. S., Miller, K. D. & Ferster, D. Inhibitory stabilization of the cortical network underlies visual surround suppression. Neuron. 62, 578–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.028 (2009).

Rubin, D. B., Van Hooser, S. D. & Miller, K. D. The stabilized supralinear network: A unifying circuit motif underlying multi-input integration in sensory cortex. Neuron. 85, 402–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.026 (2015).

Lee, S. H. et al. Activation of specific interneurons improves V1 feature selectivity and visual perception. Nature. 488, 379–383. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11312 (2012).

Wilson, N. R., Runyan, C. A., Wang, F. L. & Sur, M. Division and subtraction by distinct cortical inhibitory networks in vivo. Nature. 488, 343–348. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11347 (2012).

Atallah, B. V. et al. Reply. Nature 508, E3 https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13129 (2014).

Rikhye, R. V., Yildirim, M., Hu, M., Breton-Provencher, V. & Sur, M. Reliable sensory processing in mouse visual cortex through cooperative interactions between somatostatin and parvalbumin interneurons. J. Neurosci. 41, 8761–8778. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.3176-20.2021 (2021).

Zhu, Y., Qiao, W., Liu, K., Zhong, H. & Yao, H. Control of response reliability by parvalbumin-expressing interneurons in visual cortex. Nat. Commun. 6, 6802. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7802 (2015).

Shapiro, J. T., Gosselin, E. A. R., Michaud, N. M. & Crowder, N. A. Activating parvalbumin-expressing interneurons produces iceberg effects in mouse primary visual cortex neurons. Neurosci. Lett. 786, 136804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2022.136804 (2022).

Weaver, W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication (University of Illinois Press, 1963).

Olsen, S. R., Bortone, D. S., Adesnik, H. & Scanziani, M. Gain control by layer six in cortical circuits of vision. Nature. 483, 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10835 (2012).

Binzegger, T., Douglas, R. J. & Martin, K. A. A quantitative map of the circuit of cat primary visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 24, 8441–8453. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.1400-04.2004 (2004).

Nagel, G. et al. Light activation of channelrhodopsin-2 in excitable cells of Caenorhabditis elegans triggers rapid behavioral responses. Curr. Biol. 15, 2279–2284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.032 (2005).

Tkatch, T. et al. An efficient rAAV vector for protein expression in cortical parvalbumin expressing interneurons. Sci. Rep. 12, 17851. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-21867-0 (2022).

Dittgen, T. et al. Lentivirus-based genetic manipulations of cortical neurons and their optical and electrophysiological monitoring in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 101, 18206–18211. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0407976101 (2004).

Nathanson, J. L., Yanagawa, Y., Obata, K. & Callaway, E. M. Preferential labeling of inhibitory and excitatory cortical neurons by endogenous tropism of adeno-associated virus and lentivirus vectors. Neuroscience. 161, 441–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.03.032 (2009).

Gerits, A. et al. Serotype-dependent transduction efficiencies of recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors in monkey neocortex. Neurophotonics. 2, 031209. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.NPh.2.3.031209 (2015).

Watakabe, A. et al. Comparative analyses of adeno-associated viral vector serotypes 1, 2, 5, 8 and 9 in marmoset, mouse and macaque cerebral cortex. Neurosci. Res. 93, 144–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neures.2014.09.002 (2015).

Barthó, P. et al. Characterization of neocortical principal cells and interneurons by network interactions and extracellular features. J. Neurophysiol. 92, 600–608. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.01170.2003 (2004).

Shaw, C., Yinon, U. & Auerbach, E. Receptive fields and response properties of neurons in the rat visual cortex. Vis. Res. 15, 203–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/0042-6989(75)90208-4 (1975).

Wang, L., Sarnaik, R., Rangarajan, K., Liu, X. & Cang, J. Visual receptive field properties of neurons in the superficial superior colliculus of the mouse. J. Neurosci. 30, 16573–16584. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.3305-10.2010 (2010).

Vaiceliunaite, A., Erisken, S., Franzen, F., Katzner, S. & Busse, L. Spatial integration in mouse primary visual cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 110, 964–972. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00138.2013 (2013).

Li, Y. T., Liu, B. H., Chou, X. L., Zhang, L. I. & Tao, H. W. Synaptic basis for Differential Orientation selectivity between Complex and simple cells in mouse visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 35, 11081–11093. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.5246-14.2015 (2015).

Nathanson, J. L. et al. Short promoters in viral vectors drive selective expression in mammalian inhibitory neurons, but do not restrict activity to specific inhibitory cell-types. Front. Neural Circuits. 3, 19. https://doi.org/10.3389/neuro.04.019.2009 (2009).

Lin, J. Y., Lin, M. Z., Steinbach, P. & Tsien, R. Y. Characterization of engineered channelrhodopsin variants with improved properties and kinetics. Biophys. J. 96, 1803–1814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2008.11.034 (2009).

Butovas, S. & Schwarz, C. Spatiotemporal effects of microstimulation in rat neocortex: A parametric study using multielectrode recordings. J. Neurophysiol. 90, 3024–3039. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00245.2003 (2003).

Stark, E., Koos, T. & Buzsáki, G. Diode probes for spatiotemporal optical control of multiple neurons in freely moving animals. J. Neurophysiol. 108, 349–363. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00153.2012 (2012).

Henze, D. A. et al. Intracellular features predicted by extracellular recordings in the hippocampus in vivo. J. Neurophysiol. 84, 390–400. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.2000.84.1.390 (2000).

Yang, J. W. et al. Optogenetic modulation of a minor fraction of parvalbumin-positive interneurons specifically affects spatiotemporal dynamics of spontaneous and sensory-evoked activity in mouse somatosensory cortex in vivo. Cereb. Cortex. 27, 5784–5803. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhx261 (2017).

Muñoz, W., Tremblay, R. & Rudy, B. Channelrhodopsin-assisted patching: in vivo recording of genetically and morphologically identified neurons throughout the brain. Cell. Rep. 9, 2304–2316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2014.11.042 (2014).

Ma, W. P. et al. Visual representations by cortical somatostatin inhibitory neurons–selective but with weak and delayed responses. J. Neurosci. 30, 14371–14379. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.3248-10.2010 (2010).

El-Boustani, S. et al. Reply. Nature 508, E3-4 https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13130 (2014).

Nienborg, H. et al. Contrast dependence and differential contributions from somatostatin- and parvalbumin-expressing neurons to spatial integration in mouse V1. J. Neurosci. 33, 11145–11154. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.5320-12.2013 (2013).

Adesnik, H., Bruns, W., Taniguchi, H., Huang, Z. J. & Scanziani, M. A neural circuit for spatial summation in visual cortex. Nature. 490, 226–231. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11526 (2012).

Burne, R. A., Parnavelas, J. G. & Lin, C. S. Response properties of neurons in the visual cortex of the rat. Exp. Brain Res. 53, 374–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00238168 (1984).

Girman, S. V., Sauvé, Y. & Lund, R. D. Receptive field properties of single neurons in rat primary visual cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 82, 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.1999.82.1.301 (1999).

Bortone, D. S., Olsen, S. R. & Scanziani, M. Translaminar inhibitory cells recruited by layer 6 corticothalamic neurons suppress visual cortex. Neuron. 82, 474–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.021 (2014).

Hasse, J. M. & Briggs, F. Corticogeniculate feedback sharpens the temporal precision and spatial resolution of visual signals in the ferret. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 114, E6222–E6230. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1704524114 (2017).

Denman, D. J. & Contreras, D. Complex effects on in vivo visual responses by specific projections from mouse cortical layer 6 to dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus. J. Neurosci. 35, 9265–9280. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.0027-15.2015 (2015).

Glickfeld, L. L., Histed, M. H. & Maunsell, J. H. Mouse primary visual cortex is used to detect both orientation and contrast changes. J. Neurosci. 33, 19416–19422. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.3560-13.2013 (2013).

Cone, J. J., Scantlen, M. D., Histed, M. H. & Maunsell, J. H. R. Different inhibitory interneuron cell classes make distinct contributions to visual contrast perception. eNeuro 6https://doi.org/10.1523/eneuro.0337-18.2019 (2019).