Abstract

Load Frequency Control (LFC) is essential for maintaining the stability of Islanded Microgrids (IMGs) that rely extensively on Renewable Energy Sources (RES). This paper introduces a groundbreaking 1PD-PI (one + Proportional + Derivative-Proportional + Integral) controller, marking its inaugural use in improving LFC performance within IMGs. The creation of this advanced controller stems from the amalgamation of 1PD and PI control strategies. Furthermore, the paper presents the Mountaineering Team Based Optimization (MTBO) algorithm, a novel meta-heuristic technique introduced for the first time to effectively tackle LFC challenges. This algorithm, inspired by principles of intellectual and environmental evolution and coordinated human behavior, is utilized to optimize the controller gains. The effectiveness of the proposed methodology is rigorously evaluated within a simulated IMG environment using MATLAB/SIMULINK. This simulated IMG incorporates diverse power generation sources, including Diesel Engine Generators (DEGs), Microturbines (MTs), Fuel Cells (FCs), Energy Storage Systems (ESSs), and RES units like Wind Turbine Generators (WTGs) and Photovoltaics (PVs). This paper employs the Integral Time Multiplied by the Squared Error (ITSE) and Integral of Time Multiplied By Absolute Error (ITAE) indicators as the primary performance metrics, conventionally used to mitigate frequency deviations. To achieve optimal controller parameter tuning, a weighted composite objective function is formulated. This function incorporates multiple components: modified objective functions related to both ITSE and ITAE, along with a term addressing overshoot and settling time. Each component is assigned an appropriate weighting factor to prioritize specific performance aspects. By employing distinct objective functions for different aspects of control performance, the derivation of optimized controller gains is facilitated. The efficacy and contribution of the proposed methodology are rigorously demonstrated within the context of RES-based IMGs, featuring a comparative analysis with well-known optimization algorithms, including Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and the Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA). These algorithms are used to optimize the 1PD-PI controller, resulting in three control schemes: 1PD-PI/MTBO, 1PD-PI/WOA, and 1PD-PI/PSO. The effectiveness of these control schemes is evaluated under various loading conditions, incorporating parametric uncertainties and nonlinear factors of physical constraints. Three case studies, presented in eight scenarios (I-VIII), are utilized to comprehensively assess the efficiency, robustness, and sensitivity of the proposed approach. This analysis extends beyond the time domain, considering the stability evaluation of the proposed control scheme. Simulation results unequivocally establish the superior performance of the MTBO algorithm-optimized 1PD-PI controller compared to its counterparts. This superiority is evident in terms of minimized settling time, reduced peak undershoot and overshoot, and enhanced error-integrating performance characteristics within the system responses. Improvements are observed in both the high range and within the 80–90% range for criteria such as overshoot, undershoot, and the numerical values of the objective functions. This paper underscores the practicality and effectiveness of the 1PD-PI/MTBO control scheme, offering valuable insights into the management of frequency disturbances in RES-based IMGs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background and challenges

The increasing penetration of Renewable Energy Sources (RES) in modern power distribution systems (PDSs) has led to the emergence of Island Microgrids (IMGs). These low-voltage networks interconnect loads, Distributed Generators (DGs), and Energy Storage Systems (ESSs). However, integrating multiple DGs into PDSs presents a significant technical challenge due to their limited ability to adapt to fluctuations in energy production1,2. Unlike traditional grid-connected systems, IMGs operate as self-contained islands, requiring independent measures for power control and synchronization of power output and frequency with the central grid if necessary3. Effective operation of IMGs necessitates addressing several critical responsibilities, including voltage and frequency management, equitable load power distribution, and prompt response to load fluctuations2,3,4. Frequency deviation in IMGs directly impacts load behavior, power generation, system operation, and overall reliability. To maintain operational stability, controllers are employed to regulate the frequency within IMGs by balancing production and consumption. Meta-heuristic algorithms are used to design these controllers, which utilize time-domain performance indicators to achieve effective Load Frequency Control (LFC) in IMGs. The LFC strategy is implemented at two distinct levels: the primary level employs a control loop equipped with a droop feature to limit frequency deviations. The secondary level leverages controllers with dedicated control loops to achieve more precise frequency regulation5,6.

Literature survey

The preceding discussion underscores the emergence of a global research effort dedicated to developing LFC systems specifically tailored to the requirements of IMGs. This comprehensive research domain encompasses a broad spectrum of topics, including optimization algorithms, controllers design methodologies, and the exploration of diverse IMGs configurations. The scholarly community has demonstrably embraced these endeavors, as evidenced by the robust citation activity in relevant academic publications. The critical role of robust LFC mechanisms in maintaining frequency stability during load perturbations cannot be overemphasized. Recent years have witnessed a significant increase in scholarly publications addressing the challenges of LFC within IMGs7.

These endeavors have led to the emergence of three distinct avenues of improvement. These advancements hinge on the interplay between controller design and the optimization algorithms used to fine-tune controller parameters. The first avenue focuses on leveraging innovative and high-performance optimization algorithms8. These algorithms are applied to augment established LFC approaches, such as Proportional-Integral (PI) and Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) controllers. By optimizing the controller parameters, this approach aims to significantly enhance the efficacy of these existing control schemes. The second avenue examines novel control schemes derived from extensive literature reviews9. These schemes utilize conventional optimization algorithms to systematically eliminate factors that could compromise control performance. This optimization process is directed towards systematically refining controller parameters. The third avenue takes a synergistic approach, combining insights from the previous two. This approach involves forging a hybrid, improved controller structure. This novel structure is then meticulously optimized using a new and robust optimization algorithm. Notably, the third approach introduces a distinct advanced control scheme that stands apart from the preceding methods. Such advancements are highly valued within the academic community due to their potential to outperform existing control schemes documented in the literature. Consequently, the primary contribution of this article lies in the development presented within the third approach10,11.

A substantial body of research has explored various control methodologies to address LFC concerns in both conventional MGs and power systems12,13. In the subsequent discussion, we will review research endeavors conducted in these domains. Among these methodologies, PID controllers and their derivatives have attracted significant interest from academics and industry professionals alike. This popularity stems from several key advantages: their straightforward design, ease of tuning, proven operational reliability, minimal operator skill requirements, and a favorable balance between performance and cost considerations14. The academic literature abounds with studies employing these traditional controllers for LFC analysis in IMGs.

In addition to conventional control methodologies, researchers have actively explored various novel approaches to bolster the responsiveness of power system LFC. These advancements encompass techniques such as internal mode control7, model predictive control8, fuzzy control9,10,11,12, and robust control10,13, and the application of machine learning15,16,17. While demonstrably improving LFC responsiveness, these methods often introduce significant design complexities compared to traditional approaches. Additionally, their implementation might necessitate a high level of expertise, potentially hindering their widespread practical application.

The inherent challenges associated with LFC in IMGs stem from their low inertia and the intermittent nature of integrated RES18. To mitigate the detrimental effects of frequency deviations on consumers, the implementation of effective LFC strategies is paramount19. Within this context, a feedback loop hybrid controller plays a critical role. This controller continuously monitors frequency deviations and adjusts the output power of DGs accordingly, ensuring system stability20.

The effective and rapid tuning of controller parameters is crucial for enhancing LFC response in IMGs. To address this need, researchers have proposed numerous metaheuristic optimization algorithms18,19,20,21,22 .

Table 1 offers a comparative analysis of these algorithms, highlighting both commonalities and distinctions among relevant studies referenced in the literature. This comprehensive review methodology, derived from a meticulous analysis of the research landscape, examines the utilization of metaheuristic optimization techniques and controllers within LFC research.

Researchs gap

A significant research gap emerges from the preceding discussion, focusing on the integration of robust hybrid controllers, novel meta-heuristic optimization algorithms, and weighted hybrid time domain indices, particularly under conditions of uncertainty. Through a comprehensive analysis of existing literature and empirical evidence, the authors have identified this gap, emphasizing the need for advanced control strategies. These strategies should harness the combined strengths of hybrid controllers and meta-heuristic optimization to enhance system performance and reliability in uncertain operating conditions. Addressing this gap is crucial for advancing the field, providing a solid foundation for future research and practical applications.

Research motivation

The limitations of LFC strategies for IMGs highlight a critical need for advancement. This research paper is driven by the imperative to bridge the divide between cutting-edge theoretical advancements and their tangible application in LFC design for IMGs. This pursuit is fueled by a multifaceted motivation that aims to push the boundaries in this critical field. By resolutely addressing the identified research gap, this paper serves as a bridge, connecting theoretical advancements with practical applications. The proposed LFC framework for IMGs has the potential to be both robust and adaptable, offering a beacon of hope for enhanced system performance and reliable power supply in island communities. This research not only seeks to deliver practical solutions but also aims to contribute valuable knowledge to the ongoing academic discourse on LFC for IMGs.

Major contributions

The LFC is a critical aspect of IMG design, ensuring both frequency stability and system efficiency. Even minor frequency deviations can significantly impact IMG performance and reliability. The inherent unpredictability of RES further complicates LFC in IMG, leading to complex and unpredictable system behavior. Classical controllers, unable to handle unforeseen contingencies and uncertainties, are inadequate for managing IMG frequency42.

This paper proposes a novel and robust called 1 + Proportional + Derivative-Proportional + Integral (1PD-PI) controller to enhance LFC performance in RES-integrated IMGs. This innovative controller merges the strengths of both 1PD and PI control paradigms, contributing to its novelty and ingenuity.

To achieve effective LFC, the paper employs the recently developed Mountaineering Team-Based Optimization (MTBO) algorithm43. Inspired by mountaineering teams, MTBO utilizes a mathematical model that reflects both cognitive and environmental dynamics, mirroring human behavior. This algorithm’s simplicity lies in its reliance on only three parameters.

Within this paper, the authors leverage MTBO to fine-tune the proposed controller’s gain coefficients. The design process incorporates time-domain performance indicators, encompassing a composite objective function that systematically minimizes frequency and time deviations during optimization. A comparative analysis demonstrates the efficiency and robustness of the proposed control approach against established 1PD-PI-based optimizers: Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA)44 and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)45.

This paper presents two significant contributions to the field of LFC in IMGs. Firstly, it introduces the application of a novel 1PD-PI controller for management of frequency disturbances in IMGs. A thorough review of existing literature revealed no prior documentation of this specific controller application in this context. This novel approach highlights the paper’s innovative core. Secondly, the authors propose the MTBO methodology for LFC analysis in an IMG, with a focus on improving the optimal design of the control structure. This emphasizes the potential of the MTBO algorithm to enhance LFC performance in IMGs. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no prior research has utilized this specific framework for LFC analysis.

The significant contributions of this paper can be succinctly summarized as follows:

-

(1)

Comprehensive RES based IMG Modeling and Control Scheme Design: The paper presents a detailed investigation into the time-domain and frequency-domain behavior of the studied IMG system. This paper encompasses components such as Photovoltaic (PV) systems, Wind Turbine Generator (WTG) systems, Microturbines (MTs), Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS), Flywheel Energy Storage Systems (FESS), Diesel Engine Generators (DEGs), and Fuel Cells (FCs). It further details the dynamic modeling of these components and proposes a control scheme by strategically placing the controller within the secondary loop of the LFC system.

-

(2)

Novel 1PD-PI Controller for LFC Enhancement: This paper introduces a novel and robust 1 + Proportional + Derivative-Proportional + Integral (1PD-PI) controller specifically designed to improve LFC performance in RES-integrated IMGs. This innovative controller merges the advantages of both 1PD and PI control paradigms, resulting in a unique and effective approach. A thorough review of existing literature revealed no prior documentation of this specific controller application in this context. This novel approach highlights the paper’s originality and potential impact.

-

(3)

Leveraging the MTBO Algorithm for Optimal Controller Design: This paper introduces the application of the MTBO algorithm for optimizing the design of the proposed controller coefficients within the context of LFC analysis in IMGs. By employing this innovative optimization technique, the research explores the potential of the MTBO algorithm to enhance LFC performance in IMGs. This focus on optimal controller design through a novel optimization method underscores the paper’s contribution to the field. This contribution highlights the paper’s innovative core.

-

(4)

Weighted Combined Objective Function for Control Scheme Design: The paper introduces a novel approach for controller tuning through a weighted hybrid-objective function. This approach incorporates modified objective functions encompassing the Integral of Time Multiplied By Squared Error (ITSE) (referred to as OF1) and the Integral of Time Multiplied By Absolute Error (ITAE) (referred to as OF2), which is a widely recognized error criterion. Additionally, the function considers parameters related to settling time and overshoot within the LFC scheme of the IMG.

Furthermore, this research paper employs a multifaceted evaluation approach to strengthen the validity and originality of the proposed 1PD-PI controller and MTBO optimization technique. This approach encompasses the following key elements:

-

(1)

Comprehensive Time-Domain Simulations: The performance of the proposed controller is meticulously assessed through extensive time-domain simulations. These simulations incorporate established performance metrics, including ITSE, ITAE, OF2, and OF1. This comprehensive evaluation approach provides a thorough assessment of the controller’s effectiveness under diverse operating conditions within the IMG system.

-

(2)

Cross-Algorithm Comparison for MTBO Validation: The efficacy of the MTBO algorithm is further validated by comparing its performance against well-regarded optimizers like WOA and PSO across various IMG operating scenarios. This comparative analysis reinforces the effectiveness of the MTBO algorithm in identifying optimal controller parameters for different IMG conditions.

-

(3)

Case Studies for Robustness and Efficiency Evaluation: To evaluate the efficiency and robustness of the proposed 1PD-PI/MTBO control scheme against 1PD-PI/PSO and 1PD-PI/WOA, three case studies are designed:

-

Case Study 1: Efficiency Evaluation: This case study focuses on measuring efficiency through four scenarios (denoted as I, II, III, and IV) based on varying load demand disturbance pattern levels such as. Fixed Load Demand Disturbance Pattern (FLDDP), Random Load Demand Disturbance Pattern (RLDDP), Sinusoidal Load Demand Disturbance Pattern (SLDDP), Pulse Load Demand Disturbance Pattern (PLDDP). Scenario I serves as the baseline for designing the control schemes, with a constant load demand of 0.5 pu.

-

Case Study 2: Sensitivity Analysis: This case study focuses on assessing sensitivity through two scenarios (denoted as V, VI). These scenarios introduce uncertainties such as parametric changes (single-axis and multi-axis) to analyze the control scheme’s behavior under load disturbances.

-

Case Study 3: Robustness Evaluation: This case study delves into the robustness assessment of the proposed control scheme under load disturbances. Specifically, it focuses on evaluating the scheme’s performance in a two scenario (denoted as VII and VIII) that introduces uncertainties in the form of nonlinearities agents and physical limitations.

-

For each scenario, the analysis extends beyond frequency response to include metrics like overshoot, settling time, undershoot, and the numerical values of performance indices (ITSE, ITAE, OF2, OF1). This comprehensive evaluation approach allows for a nuanced understanding of the control scheme’s performance across different operating conditions.

These contributions collectively represent significant advancements in the field of LFC within IMGs, providing innovative insights and practical solutions for enhancing frequency regulation and overall IMGs performance. Building upon our comprehensive review of the existing literature, this paper injects significant novelty into the field of LFC for IUMGs by introducing two paramount contributions. Firstly, the paper leverages the 1PD-PI controller, marking a groundbreaking approach within the LFC domain. This novel control strategy has not been previously explored for IMGs frequency regulation, offering a fresh perspective for tackling this critical challenge. Secondly, the design of the proposed controller prioritizes the pioneering integration of the MTBO. By harnessing the MTBO ‘s algorithm capabilities for LFC design in IMGs, this paper represents the first of its kind in this specific domain. These distinctive contributions underscore the originality and potentially transformative impact of this research paper on the advancement of IMG-based LFC strategies, thereby setting this paper apart from prior research endeavors.

Figure 1 depicts the graphical representation of the present work.

Organization of the paper

The subsequent sections of this paper will delve into the following topics: Sect. "System modeling of RES-based proposed IMG" will elucidate the system modeling of the proposed IMG based on RES. Section "Introduction to MTBO algorithm" will provide a comprehensive explanation of the MTBO technique and its practical applications in the LFC problem. Section "Objective function" will explore the objective functions in depth. Section "Cascade control approach" will describe the proposed controller and detail its operational mechanisms. Section "The proposed control scheme" will thoroughly dissect the process of controller design, relying on the MTBO optimizer. Section "Simulation results" will be dedicated to evaluating the proposed LFC model through simulation tests. Section "Results analysis and discussion" will present and thoroughly analyze the simulated results and discussions obtained from the IMG. Section "The advantages of the proposed approach" will expound upon the merits of adopting the proposed approach. Section "Conclusion and remarks" will provide the concluding remarks, and Sect. "Future research approaches" will delineate suggestions and future research avenues.

System modeling of RES-based proposed IMG

The study presents a comprehensive IMG configuration in Fig. 2. This configuration effectively meets load demands and facilitates bidirectional data exchange through communication links and power lines. Figure 2 provides a detailed schematic diagram of the IMG, illustrating its constituent components. These components include PV, WTGs, DEGs, FCs, MTs, BESS, FESS, the AC bus, power electronic converters, Circuit Breakers (CBs), and electric loads.

Figure 3 illustrates the methodology for integrating Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) into the IMG. This process involves two primary converter types: AC/AC Converters: These synchronize the AC bus with individual WTG, DEG, and MT units connected to it, ensuring seamless power exchange46. DC/AC Interface Inverters: Employed for integrating PV, FC, BESS, and FESS units into the AC bus47,48. These converters facilitate voltage and current synchronization between these DC sources and the AC system. The CBs are strategically placed throughout the IMG to safeguard various subsystems from potential damage during severe disturbances. Their precise positioning ensures targeted isolation in case of faults, minimizing disruption to the entire system49,50,51,52,53,54.

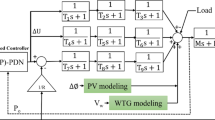

Figure 4 illustrates the configuration of components within the examined IMG, where the inputs consist of solar radiation flux for PV and wind power for WTG. The LFC is executed through controllable elements, namely DEG, MT, and FC, operating within a secondary control loop governed by a dedicated controller. The secondary control loop’s controller is responsible for regulating the output power of controllable distributed generation sources, including DEG, MT, and FC, to maintain the frequency of the IMG within desired limits. Due to the intermittent nature of power outputs from WTG and PV subsystems, denoted as ΔPWT and ΔPPVs, respectively, stemming from their dependence on weather conditions, these subsystems are excluded from the control loop. Throughout this study, we have ignored the models of power electronic converters utilized in the investigated IMG to facilitate a clearer understanding of its frequency response. Consequently, the frequency response model incorporates simplified linearized first-order transfer function models for the PV, WTG, DEG, FC, MT, BESS, and FESS subsystems. As LFC predominantly involves small signal analysis, certain RES and ESS may possess higher-order transfer function models. However, lower-order transfer function models suffice for their representation in the context of LFC. The ESS units play a vital role in stabilizing frequency deviations within a IMG by functioning as local active power sources, thereby exchanging power with RES. Given RES’s relatively slow response time, ESS supplements their contribution to enhanced LFC55,56,57,58. Subsequently, we will provide a concise overview of the IMG subsystems under examination, with detailed parameter values for the IMG in Table 2.

WTG model

WTGs are inherently variable power sources due to fluctuations in wind profiles, introducing instability into the grid59,60 .To account for this variability within the IMG model, the WTG is represented as a component that injects power fluctuations. Pwind and Pmech of the WTG are determined by Eqs. (1)–(2) as presented in61:

The power coefficient, Cp, and several other physical parameters are combined to calculate the resultant power of the WTG, as previously mentioned and reiterated in numerous publications62,63,64,65. Cp, which represents the power-capturing efficiency of the WTG, is influenced by two primary factors: λ and β, It is defined as follows :

where λi satisfies the following Eq. (4):

Among the DER units integrated within the IMG, WTG is chosen in this paper to represent a variable power source due to their minimal impact on the IMG’s frequency response. This selection enables analysis to focus on the influence of variable power generation without the added complexity of WTG frequency dynamics. Figure 5 presents a detailed mathematical model of a real WTG system for in-depth analysis. Readers interested in a more comprehensive theoretical foundation for WTG modeling can refer to references62,63,64. While WTGs inherently exhibit non-linear behavior, this paper employs a simplified approach to enhance tractability. The WTG is modeled as a first-order lag transfer function, as described by Eq. (5). This linearization facilitates the investigation of the IMG’s frequency response characteristics.

PV model

The PV systems are widely integrated into IMGs due to their advantages in harnessing abundant solar irradiation and offering ease of installation66,67. However, their power production is highly dependent on two crucial environmental factors: solar irradiance level and ambient temperature68,69,70,71. To determine the output power of PV systems within an IMG, the following equation can be employed:

The transfer function of the PV system is characterized by a first-order lag, as represented by Eq. (7)68. :

Figure 6 presents a mathematical model of a real-world PV system63.

Energy storage systems model

The ESS is an arrangement of one or more devices designed to capture electrical energy from power sources and store it for later use72,73,74,75. In this paper, the ESSs encompass FESS, BESS, and FC.

BESS model

The BESS are electrochemical devices storing energy from power grids, promoting efficient electricity utilization, and integrating RESs72,76 Linearized first-order transfer function model for BESS system are described by Eq. (8):

FESS model

The FESS harnesses kinetic energy stored within a rotating mass characterized by minimal frictional losses. This system stores input electrical energy in the form of kinetic energy72. Linearized first-order transfer function models for the FESS system are expressed by Eq. (9).

FC model

The FCs are clean, efficient energy sources in IMGs, generating electricity using hydrogen or other fuels for enhanced performance72. FC integration can be tailored to suit different power scales and applications, with linearized first-order models outlined in Eq. (10).

MT model

The MT represents a relatively recent advancement in stationary power generation technology, akin to combustion turbines operating at a significantly reduced scale, producing heat and electricity77. The linearized first-order transfer function models for the MT system are given in Eq. (11).

DEG model

The DEG combines a diesel compression ignition engine with an electric generator for electricity generation, typically diesel fuel, with some variants compatible with other powers or natural gas78,79,80. The linearized first-order transfer function models describing the DEG system are presented in Eq. (12).

IMG system dynamics model

The overall frequency response model of the IMG with dynamics model could be expressed as;

Eventually, the combined electrical power generated by RESs and energy ESSs units to meet the load demand is represented by the following Eq. (14):

The ± sign before ∆PBESS and ∆PFESS in Eq. (14), the BESS and FESS units are charged and discharged. If a + sign is displayed, the BESS or FESS are discharging; if a - sign is displayed, they are charging.

Introduction to MTBO algorithm

Metaheuristic optimization algorithms were developed to address the limitations of traditional techniques, particularly in LFC issues, addressing complexity and local optima in optimization81 .

Among these metaheuristic optimization algorithms, the PSO and WOA stand as prominent metaheuristic algorithms frequently employed for addressing LFC challenges82,83. The WOA approach represents an optimization technique grounded in three distinct operators that emulate the hunting, surrounding, and bubble-net foraging behaviors observed in humpback whales44. Likewise, the PSO algorithm draws its inspiration from the extensively documented and comprehended individual as well as collective behaviors observed in birds during hunting and navigation45.

In contrast to the aforementioned algorithms, the MTBO algorithm emerges as a compelling choice for LFC design in IMGs due to its versatility and effectiveness in tackling optimization problems84. The MTBO algorithm’s strength lies in its adaptability and relative simplicity, requiring only three control parameters (Li, Ai, and Mi) for operation .This characteristic translates to enhanced computational efficiency, making it particularly well-suited for addressing LFC challenges within IMGs. This paper recommends adopting the MTBO algorithm due to its simplicity and computational efficiency.

Subsequent sections briefly explore the algorithm’s inspirations and mathematical formulations. For a comprehensive understanding of the MTBO algorithm’s underlying principles and mathematical formulations, readers are directed to reference43. This reference provides an in-depth exploration of the algorithm’s theoretical foundation. Figure 7 also shows the MTBO algorithm flowchart throughout the optimization phase.

Inspiration

The MTBO algorithm, rooted in social interaction and teamwork, simulates climbing while considering natural factors guided by a leader. MTBO comprises four phases: mirroring mountaineering, addressing disasters’ impact, promoting group coordination, and mitigating avalanche risks.

The MTBO algorithm is inspired by social interaction and collaboration principles, with a rigorous mathematical formulation. It simulates an ascent to a summit while considering natural phenomena. It examines climbers’ mobility phases, using a leader’s knowledge to navigate challenges and avoid local optima. Additionally, it outlines how groups cooperate to protect members from natural hazards.

Mathematical model

Mathematical modeling of the MTBO algorithm is in four stages as follows43:

First phase: coordination of mountaineering activities

The MTBO involves an experienced climbing team member selecting the best solution, leading the group toward its goal, and the algorithm’s population follows. Consequently, the group follows the lead of this member in the following manner:

Mountaineering teams use the MTBO algorithm, guiding group actions with skill-ranked leaders and front-line members. As a result, the equation for regular travel toward the peak is altered as follows43:

Where Xii is the individual member’s position as dictated by the person immediately in front, the pseudo-code for this phase is as follows since everything occurs at random in the realm of optimization, and the probability of this phase is considered equal to Li.

S phase: natural disasters and their effects

Mountaineers risk getting stuck in local optima, affecting progress and safety. The MTBO algorithm considers avalanches and cliff falls, significantly influencing the optimization process. Thus, for the MTBO, the critical situation is equivalent to the worst-case scenario of the algorithm in the event of an avalanche occurring randomly in nature, XWorst or its equivalent XAvalanche, and that in the event of an avalanche and other calamities, the ith individual attempts to escape the calamity situation, XWorst or its equivalent XAvalanche, and save herself/himself through Eq. 18:

As a guide to this phase, the pseudo-code is as follows, with the assumption that the likelihood of an avalanche occurring is equal to Ai:

Third phase: coordination and group effort to combat disasters

A climbing team’s ability to work together socially and cooperatively is crucial. As a result, in the event of a tragedy or being stuck, the mountaineering team will attempt to rescue the stranded member. By coordinating and cooperating with the group, the MTBO is motivated to assist the trapped member, i.e., the positions of all members are equal to their average positions, Xmean or XTeam that the ith person is toward; this behavior is depicted as follows:

A pseudo-code for this phase, the following is provided: The chance of rescuing a person caught in an avalanche, or to put it another way, stuck in the ideal local solution, is considered equal to Mi.

Fourth phase: possibly fatalities among members

Despite the precautions taken, avalanches remain a life-threatening risk in mountaineering. In the MTBO algorithm, when a member is eliminated, a new member is randomly selected using Eq. (22) to replace them:

Objective function

The design of LFC prioritizes achieving a rapid rise time, minimal overshoot, and brief settling time. Optimization algorithms and disturbance management techniques are employed to attain these objectives and minimize errors in the LFC system’s response85. The formulation of an effective objective function plays a critical role in the LFC process. This function guides the optimization process towards reduced error and optimized system response86,87,88. For the optimization of 1PD-PI controller parameters, a well-defined objective function is necessary to minimize a specific cost metric.

This paper proposes a modified composite objective function (Eqs. 23, 24) that incorporates adjusted ITSE (denoted as OF1) and ITAE (denoted as OF2) indices, along with overshoot and settling time considerations.

Effective performance hinges on assigning appropriate weights (w1, w2, and w3) to the error functions, settling time, and overshoot within the objective function. M and N represent the peak overshoot and settling time (within a 2% band) observed in the system’s response, respectively. In this study, w1, w2, and w3 are assigned values of 0.6, 0.2, and 0.2, respectively.

The design of controllers relies on objective functions like OF1 and OF2. However, during the evaluation stage of the proposed control scheme, the performance analysis extends beyond these two functions. In addition to OF1 and OF2, the ITAE and ITSE indices are also employed for a more comprehensive evaluation. This multifaceted approach provides a clearer understanding of the controller’s effectiveness.

Cascade control approach

Cascade control manages two sequential processes: the inner process feeding into the outer process. It uses two control loops, as shown in Fig. 8. The outer loop controls the final process output’s quality, while the inner loop handles supply disturbances and internal disruptions’ impact on the outer process. Cascade control excels at swiftly suppressing disturbances89.

Figure 8 displays the process output, Y(s), carried by the outer loop and managed by the primary control to achieve the desired reference signal, R(s). G1(s) represents the outer process, and d1(s) is presumed to be the load disturbance affecting the entire system. Equation (25) presents the mathematical description of the outer loop.

Where:

Assuming d1(s) equals zero, the input from the outer process, denoted as u1(s), becomes the output from the inner process, represented by, y2(s). The inner loop encompasses the inner or supply process G2(s), and its equation is provided by Eq. (27).

With u2(s) serving as the input to the inner process, the inner loop promptly addresses variations in the internal process gain resulting from set point changes or disruptions.

1PD-PI controller

The LFC in MGs are tasked with regulating frequency and generation deviations to zero in response to various disturbances. These disturbances can include sudden changes in load demand, uncertainties in system parameters, and unforeseen disruptions. This regulation process entails the calculation of an Area Control Error (ACE), which serves as the input for the controller to generate a control signal that adjusts generation within the IMG.

Classical controllers, known for their reliability, straightforward design, minimal user expertise requirements, and satisfactory performance, remain a popular choice among researchers in LFC design. Particularly attractive are single-input, single-output classical controllers, which excel in prioritizing stability and achieving rapid responses – crucial characteristics in LFC systems.

However, the growing integration of RESs and other unspecified conditions into IMGs presents a significant challenge for classical controllers. The inherent unpredictability of RES output makes it difficult for these controllers to effectively maintain frequency stability under unforeseen circumstances. Our previous literature survey extensively explores classical controllers, such as PI or PID, highlighting their merits and drawbacks.

While established classical LFC approaches offer undeniable advantages, the cascade combination of 1 + Proportional-Derivative (1PD) and Proportional-Integral (PI) controllers has received comparatively less research focus. Given the potential for this configuration to enhance LFC performance, this paper delves into its application within diverse IMGs coupled with RESs. The proposed control strategy leverages a 1PD-PI cascade controller structure. This configuration features an outer loop comprised of a 1PD controller, responsible for the primary control process. The inner loop, serving as a secondary control mechanism, employs a PI controller. This amalgamation of controllers capitalizes on the strengths of both PD and PI control, offering a promising avenue for improved LFC performance in IMGs with RESs.

The structure of the 1PD-PI controller is illustrated in Fig. 9, with KP, KD, KPP, and KI representing proportional, derivative, proportional, and integral gains, respectively. C1(s) and C2(s) are the selected controllers for the outer and inner roles, respectively. In this setup, the 1PD controller is the outer controller, while the PI controller is the inner controller. The ACE signal serves as input to the 1PD controller, while the PI controller generates the output control signal or the plant input signal ΔPref.

As shown in Fig. 9, the ACE signal can be defined using Eq. (28).

As a result, the general control rule that links ACE to ΔPref may be written as the following Eq. (29):

The proposed control scheme

This paper introduces the MTBO algorithm, a novel approach to optimizing the LFC problem. The algorithm draws inspiration from both cognitive evolutionary theory and the collective behavior observed in human mountaineering teams.

A central challenge in LFC applications concerns the optimal design of the four-gain 1PD-PI controller. This paper proposes the MTBO algorithm for the specific task of simultaneously optimizing the parameters within this controller structure, which operates within the secondary LFC loop of IMGs. The effectiveness of the MTBO algorithm hinges on its ability to minimize a well-defined objective function that governs controller performance.

Equation 30 details the permissible range for parameter adjustments within the proposed controllers, with max and min representing the upper and lower bounds, respectively.

Figure 10 illustrates the linkage between the Simulink-MATLAB simulation environment and the MATLAB workspace, while, Fig. 11 depicts the flowchart of the proposed control strategy. Notably, this connection facilitates the incorporation of frequency deviation parameters into the objective function definition.

The selection of an appropriate search space for the MTBO algorithm hinges on the number of individuals, also referred to as climbers, which are defined as population. In the design process presented here, a population size of 50 individuals was chosen. In the design process, a pivotal factor that serves as a termination criterion is the number of iterations. The optimization process was executed for 60 iterations, with a computational time of approximately 20 s.

In contrast, Table 3 provides a comprehensive overview of the control parameters by the PSO and WOA and MTBO optimizers. Furthermore, some initial configurations, which are common to all three optimizers, are succinctly summarized in Table 4 below. Table 5 summarizes the optimized controller gains obtained through the design process. Notably, the results presented in this table are based on the implementation of Scenario I from the case studies. This scenario, characterized by a constant load demand of 0.5 pu, serves as the reference point for designing the proposed control schemes.

Simulation results

Assessment settings and specifications

This section details the simulation environment and evaluation methodology employed to validate the proposed control strategy.

System configuration

The paper investigates the performance of the proposed control scheme within a RES-based IMG, as depicted in Fig. 4. The simulations are executed using MathWorks MATLAB/Simulink software (version R2023b) installed on a personal computer with the following specifications: Microsoft Windows 11 operating system, Intel® Core™ i5-14600 K CPU (3.50 GHz), and 32 GB of RAM.

Control scheme design

This paper investigates the design of a 1PD-PI controller for application within the LFC secondary loop in the proposed IMG. It utilizes optimization techniques to fine-tune the controller’s gains. Three distinct optimization algorithms are employed for this purpose: MTBO, WOA, and PSO. By applying each optimization technique to the 1PD-PI controller design, the research generates three distinct control schemes: 1PD-PI/MTBO, 1PD-PI/WOA, and 1PD-PI/PSO. These schemes are subsequently evaluated for their effectiveness in management of frequency disturbances within the IMG.

Evaluation scenarios

To comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed control schemes, a series of eight distinct scenarios (denoted as I-VIII) are distributed across three case studies:

-

Case Study 1: Performance Evaluation (Scenarios I-IV): This case study focuses on assessing the control schemes’ (such as1PD-PI/MTBO, 1PD-PI/WOA, and 1PD-PI/PSO) overall performance under various loading conditions. Scenarios I through IV encompass a range of loading patterns, including FLDDP, RLDDP, SLDDP, PLDDP. This comprehensive analysis ensures a thorough evaluation of the control schemes’ behavior under diverse loading conditions.

-

Case Study 2: Sensitivity Analysis (Scenarios V-VI): This case study investigates the sensitivity of the proposed control scheme i.e. 1PD-PI/MTBO to specific IMG parameters. Scenarios V and VI involve variations in key parameters relative to Scenarios III and I (with SLDDP and FLDDP loading patterns, respectively). By analyzing the control schemes’ response to these parameter variations, this case study assesses their scalability in adapting to changing IMG conditions.

-

Case Study 3: Robustness Evaluation (Scenarios VII-VIII): This case study delves into the robustness of the control schemes’ (such as1PD-PI/MTBO, 1PD-PI/WOA, and 1PD-PI/PSO) under the influence of non-linearities (i.e. physical limitation, time delay). Scenarios VII and VIII introduce these limitations (building upon Scenarios II and IV with RLDDP and PLDDP loading patterns, respectively) to evaluate the control schemes’ robustness to maintain IMG stability even in the presence of such challenges.

This structure allows for a systematic evaluation process, starting with a broad assessment of performance under various loading conditions (Case Study 1), followed by an investigation of sensitivity to specific parameters (Case Study 2), and culminating in an exploration of robustness under non-idealities (Case Study 3). The detailed specifications for each scenario are presented in Table 6 for further reference.

Simulating real-world weather impacts on IMG operation

The effectiveness of the LFC strategy hinges on its ability to manage the inherent variability associated with RESs. This section details the methodology employed to incorporate real-world weather data into the simulation environment, ensuring the robustness of the validation process.

The PV and WTG systems are particularly susceptible to fluctuations in weather conditions. To account for this dynamic nature, the paper utilizes real-time recorded wind data. A random variation curve, depicted in Fig. 12, is generated based on the changes in wind power (ΔPwind) and solar irradiance (Δφsolar) observed in this data. This curve represents the dynamic fluctuations in power input to the IMG from these RESs.

The Fig. 12 random variation curve, reflecting real-world weather patterns, is consistently applied as the input for the PV and WTG systems across all investigated scenarios. The corresponding outputs from these systems, namely the variations in power output from the PV system (ΔPPV) and the WTG system (ΔPWTG), are then incorporated into the simulation model to assess their impact on the overall IMG operation, as illustrated in Fig. 13.

This approach ensures that the control strategy’s performance is evaluated under realistic operating conditions that replicate the dynamic power fluctuations characteristic of RES-based generation.

Case study 1: performance evaluation

This case study investigates the control schemes’ performance under varying load demand conditions. Four distinct scenarios (denoted as I, II, III, and IV) are employed, each characterized by a unique load demand profile: FLDDP, RLDDP, SLDDP, PLDDP. Scenario I serves as the baseline, utilizing a constant load demand of 0.5 pu and informs the controller design process. The primary objective of this case study is to evaluate the efficiency of the control schemes (such as1PD-PI/MTBO, 1PD-PI/WOA, and 1PD-PI/PSO) in handling these diverse load demand profiles.

Scenario I: FLDDP analysis

Baseline design control schemes

This scenario serves as the benchmark for designing the controllers. A FLDDP of 0.5 pu is applied to the IMG to establish a baseline for comparison. Figure 14 illustrates the FLDDP loading in this scenario. The convergence curves for the optimization algorithms, namely, MTBO, WOA, and PSO, employed in the proposed controller design process are depicted in Fig. 15. These curves visualize the convergence behavior of the algorithms towards an optimal solution.

Frequency response analysis of scenario I

Figure 16 presents the frequency response of the IMG under the FLDDP with the implemented control schemes. As observed in Fig. 16, the 1PD-PI/MTBO control scheme exhibits superior performance in mitigating frequency disturbances. This suggests that the MTBO optimization algorithm effectively tunes the 1PD-PI controller parameters, resulting in a more robust response to frequency deviations. In this specific case (1PD-PI/MTBO), the MTBO algorithm identified a combination of controller gains that minimizes settling time, overshoot, and undershoot in the frequency response. This translates to faster stabilization of the system’s frequency after a disturbance and less deviation from the desired operating point.

Power sources response analysis of scenario I

Figure 17 shows the output power of the DEG, FC, and MT units. These conventional sources provide additional power and contribute to system stability. Figure 18 illustrates the power exchange of the BESS and FESS units. These storage systems can absorb or inject power to regulate frequency and maintain system balance.

Comparative evaluation of scenario I

Table 6 provides a quantitative comparison of the control schemes based on time-domain indicators extracted from the frequency response analysis in Fig. 16. These indicators include settling time, overshoot, undershoot, and the numerical values of performance indices like OF1, OF2, ITSE, and ITAE. According to the Table 7, the 1PD-PI/MTBO control scheme achieves shorter settling times, lower overshoots, and faster damping of frequency excursions compared to the other control schemes. These results suggest that 1PD-PI/MTBO demonstrates superior effectiveness and efficiency in maintaining frequency stability under FLDDP conditions.

Scenario II: RLDDP analysis

This scenario evaluates the control schemes’ performance under a more dynamic load condition: RLDDP. Figure 19 depicts the RLDDP, highlighting the fluctuating nature of the load demand on the IMG. This scenario presents a more rigorous test for the control schemes, requiring them to maintain frequency stability despite unpredictable load variations.

Frequency response analysis of scenario II

Figure 20 presents the frequency response of the IMG under RLDDP when employing the control schemes (1PD-PI/MTBO, 1PD-PI/WOA, and 1PD-PI/PSO). Notably, Fig. 20 demonstrates the success of the 1PD-PI/MTBO control scheme in mitigating frequency disturbances under RLDDP. Compared to Scenario I, the frequency deviations are demonstrably reduced, and the system exhibits a faster rate of regaining stability. This enhanced performance under RLDDP can be attributed to the effectiveness of the MTBO optimization algorithm. By dynamically adapting the controller parameters during the design process, the MTBO algorithm likely equipped the control scheme to handle the dynamic load variations more effectively. This translates to a more robust response to load fluctuations and quicker stabilization of the system’s frequency.

Power sources response analysis of scenario II

Figures 21 and 22 depict the power output behavior of the generating units (DEG, FC, and MT) and the ESSs units (FESS and BESS), respectively.

Comparative evaluation of scenario II

Similar to Scenario I, Table 8 provides a quantitative comparison of the control schemes based on time-domain indicators extracted from the frequency response analysis in Fig. 20. These indicators include overshoot, undershoot, and performance indices like OF1, OF2, ITSE, and ITAE.

Scenario III: SLDDP analysis

This scenario investigates the performance of the control schemes under a SLDDP. Unlike the random fluctuations of the previous scenarios, an SLDDP introduces a periodic and predictable variation in the load demand on the IMG. This predictable pattern is defined by the mathematical model in Eq. 31 and visually represented in Fig. 23.

Frequency response analysis of scenario III

Figure 24 presents the frequency response of the IMG under the SLDDP when employing the control schemes (1PD-PI/MTBO, 1PD-PI/WOA, and 1PD-PI/PSO). Figure 24 shows that the 1PD-PI/MTBO control scheme demonstrates effectiveness in mitigating frequency disturbances under the SLDDP. The control scheme ensures the system maintains stability with minimal oscillations around the desired operating point.

The effectiveness of the MTBO optimization algorithm in tuning the controller parameters plays a crucial role here. Since the SLDDP is a predictable disturbance, the MTBO algorithm might have identified controller settings that enable the system to anticipate and counteract the load variations more precisely. This translates to a more controlled response to the sinusoidal load changes and minimizes frequency deviations.

Power sources response analysis of scenario III

Figures 25 and 26 depict the response of power sources within the IMG under SLDDP and the implemented control schemes. Figure 25 shows the frequency response, while Fig. 26 illustrates the output power behavior of the conventional generating units (DEG, FC, and MT) and the ESSs units (BESS and FESS).

Comparative evaluation of scenario III

Similar to previous scenarios, Table 9 provides a quantitative comparison of the control schemes based on time-domain indicators extracted from the frequency response analysis in Fig. 24. These indicators include overshoot, undershoot, and performance indices like OF1, OF2, ITSE, and ITAE.

Scenario IV: PLDDP

This scenario investigates the performance of the control schemes under a PLDDP. Unlike the previous scenarios, the PLDDP introduces a sudden and short-lived increase in the load demand on the IMG. This type of disturbance can be challenging to manage due to its rapid nature. Figure 27 depicts the PLDDP, characterized by a 50-second duration and an amplitude of 0.08 MW pu.

Frequency response analysis of scenario IV

Figure 28 presents the frequency response of the IMG under the PLDDP when employing the control schemes (1PD-PI/MTBO, 1PD-PI/WOA, and 1PD-PI/PSO). Figure 28 shows that the 1PD-PI/MTBO control scheme effectively manages frequency disturbances under the PLDDP. Following the sudden load increase, the system frequency exhibits a brief deviation, but the control scheme quickly counteracts this change and restores the frequency to its desired operating point.

Power sources response analysis of scenario IV

Figures 29 and 30 depict the response of power sources within the IMG under PLDDP and the implemented control schemes. Figure 29 shows the output power of the conventional generating units (DEG, FC, and MT), while Fig. 30 illustrates the response of the ESSs units (BESS and FESS).

Comparative evaluation of scenario IV

Table 10 provides a quantitative comparison of the control schemes based on time-domain indicators extracted from the frequency response analysis in Fig. 28. Similar to previous scenarios, these indicators include overshoot, undershoot, and performance indices like OF1, OF2, ITSE, and ITAE.

Case study 2: sensitivity analysis

This case study investigates the sensitivity of the proposed control scheme (i.e. 1PD-PI/MTBO) to variations in IMG parameters. Two scenarios, V and VI, are employed to analyze the control system’s behavior under different uncertainty conditions: uniaxial and multiaxial parameter variations.

This case study employs two load demand profile models, SLDDP and FLDDP, as inputs for the IMG to ensure realistic representations of real-world demand patterns. A sensitivity analysis is subsequently conducted through Scenarios V and VI. Scenario V leverages the settings established in Scenario III, while Scenario VI utilizes the settings from Scenario I. Both scenarios involve step changes in key IMG parameters to assess the system’s sensitivity.

The analysis focuses on investigating the effects of modifying specific parameters within the IMG system. These parameters include the time constants of controllable units: FC (TFC), DEG (TDEG), and MT (TMT). Additionally, the analysis considers parameters of the IMG system dynamics model itself: Inertia constant (M) and load damping coefficient (D). All aforementioned parameters are subjected to ± 50% variations from their nominal values.

Scenario V: analysis of uniaxial sensitivity effects for SLDDP

The Uniaxial analysis provides valuable insights into how the LFC system responds to individual parameter changes. This approach allows for identifying the parameters that exert the most significant influence on system performance. In Scenario V, each of the aforementioned parametric uncertainties is applied independently. The frequency response of the system under each individual parameter change is analyzed to isolate the specific effect of that variation. All other IMG settings are maintained identical to Scenario III to facilitate a controlled comparison. The resulting time-domain evaluation indices of the frequency response are presented in Table 11. This analysis enables a comprehensive understanding of how each individual parameter uncertainty affects the IMG’s performance.

Scenario VI: analysis of multiaxial sensitivity effects for FLDDP

Real-world parameter variations rarely occur in isolation. Multiaxial analysis provides a more realistic assessment of the control system’s robustness by considering the combined effects of multiple uncertainties.

Scenario VI employs a multiaxial sensitivity analysis to comprehensively assess the IMG’s sensitivity to a wider range of parameter uncertainties. All other IMG settings are maintained identical to Scenario I to facilitate a controlled comparison.

Unlike Scenario V, all previously identified parameter uncertainties are applied simultaneously to the IMG model in two instances: once with a + 50% change and another time with a -50% change for each parameter. This approach allows for investigating the combined effects of multiple parameter variations. All other settings remain consistent with Scenario I, enabling a direct comparison with the scenario I.

Figure 31 presents the frequency response of the IMG under the 1PD-PI control scheme designed using the MTBO technique within the context of Scenario VI. This response is depicted for both + 50% and − 50% variations in key IMG parameters. It is important to note that Scenario VI utilizes settings established in Scenario I, allowing for a comparison with the baseline response established in Scenario I.

Case study 3: robustness evaluation

Conventional analyses of LFC schemes in IMGs often rely on linear models, neglecting the non-linearities and physical limitations inherent in real-world IMGs. This shortcoming can lead to inaccurate assessments of control scheme performance. To address this gap, Case Study 3 incorporates these factors into the evaluation process, enhancing the robustness of the analysis.

Rationale and methodology

Existing LFC research in IMGs frequently overlooks non-linearities and physical limitations, potentially leading to unrealistic performance evaluations. To bridge this gap, this case study incorporates two key considerations:

Physical limitations

Physical limitations inherent to equipment capacity and complexity can significantly hinder the operation and control of MGs. This paper focuses on such limitations associated with ESSs, particularly a deadband in their response to frequency fluctuations (Δf) experienced at the model input. Deadbands are modeled by ± ζBESS and ± ζFESS for BESS and FESS, respectively, with a value of 0.05 chosen for this paper.

Time delay

Communication delays inherent in signal transmission can significantly impair system performance, potentially leading to instability. This phenomenon occurs because electronic devices in power sources, such as ESSs, generally activate only when frequency deviations surpass ± 20 mHz at a nominal frequency of 50 Hz. To mitigate these communication delays, this paper incorporates a time delay (τ) of 20 s into the controller’s output (ΔPref), specifically the control signals for three controllable units: FC, DEG, and MT, as well as the before power output paths of BESS (ΔPBESS) and FESS (ΔPFESS). This time delay models the combined impact of delays in receiving information from the units and transmitting measurement power data for BESS and FESS.

Modeling non-linear operating conditions

Finally, Fig. 32 applies time delay and physical limiters to BESS and FESS and applies time delay to the output of the proposed controller. This modeling introduces non-linear factors into the IMG, transforming the purely linear model presented in Fig. 4 into a more comprehensive representation that reflects real-world operating conditions. This enhanced model allows for a more rigorous evaluation of the proposed control schemes’ robustness in maintaining system stability under these non-idealities.

Scenario design for non-linear operating conditions

Scenarios VII and VIII build upon Scenarios II and IV with RLDDP and PLDDP loading patterns, respectively. By introducing the aforementioned physical limitations and time delay into these scenarios, Case Study 3 evaluates the robustness of the proposed control schemes (e.g., 1PD-PI/MTBO, 1PD-PI/WOA, and 1PD-PI/PSO) under non-ideal operating conditions that more closely resemble real-world IMGs. This allows for a more comprehensive assessment of their ability to maintain system stability.

Scenario VII: effects of time delay and physical limitations for RLDDP

This Scenario investigates the effects of incorporating time delay and physical limitations into Scenario II, which utilizes RLDDP modeling. Figure 33 depicts the frequency response of the IMG under RLDDP when employing the 1PD-PI/MTBO, 1PD-PI/WOA, and 1PD-PI/PSO control schemes. Notably, Fig. 33 demonstrates the success of the 1PD-PI/MTBO scheme in mitigating frequency disturbances under RLDDP, mirroring the performance observed in Scenario II.

Scenario VIII: effects of time delay and physical limitations for PLDDP

Similar to Scenario VII, this section investigates the impact of incorporating time delay and physical limitations into Scenario IV, which employs PLDDP modeling. Figure 34 depicts the frequency response of the IMG under PLDDP when employing the 1PD-PI/MTBO, 1PD-PI/WOA, and 1PD-PI/PSO control schemes. It is important to note that, as observed in Scenario IV, Fig. 34 again demonstrates the effectiveness of the 1PD-PI/MTBO scheme in mitigating frequency disturbances under PLDDP loading conditions.

Evaluating sustainability impacts

The proposed control method, the 1PD-PI controller designed using the MTBO technique (referred to as 1PD-PI/MTBO), offers significant advantages for the environmental and sustainability performance of IMG systems through its demonstrably enhanced stability characteristics.

-

Reduced Emissions and Improved Fuel Economy: The 1PD-PI/MTBO controller’s ability to effectively mitigate frequency deviations and load fluctuations translates directly to potential reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. This stability enhancement ensures optimal operation of controllable power sources (e.g., DEG) and minimizes unnecessary load shedding events. Consequently, the controller promotes more efficient use of fossil fuels, leading to lower overall emissions.

-

Enhanced Integration of RES: The robust performance of the 1PD-PI/MTBO controller under varying operating conditions facilitates a smoother integration of RES with inherent variability (e.g., WTG and PV). This stability improvement allows the controller to effectively manage fluctuations in power generation from RESs, enabling a greater reliance on these sustainable sources and ultimately contributing to a more sustainable energy mix for the IMG.

-

Improved System Efficiency and Reduced Losses: The superior performance of the 1PD-PI/MTBO controller in regulating system frequency and power flow translates to potential reductions in energy losses within the IMGs. By minimizing unnecessary power fluctuations and maintaining stable operating conditions, the controller promotes more efficient energy transmission and distribution, leading to overall energy savings and a reduced environmental footprint for the IMG.

Eventually, the 1PD-PI/MTBO controller presents a compelling approach for enhancing the environmental and sustainability performance of IMGs. By prioritizing stability analysis and demonstrably improving system stability, this controller facilitates efficient operation of power sources, enables greater reliance on RESs, and ultimately contributes to a more sustainable and environmentally friendly MG operation. While the 1PD-PI/MTBO controller offers promising environmental and sustainability benefits, it is essential to acknowledge certain limitations. The actual reduction in emissions and improvement in fuel economy achieved will depend on the specific configuration of the IMG and the energy mix utilized. Additionally, further research might be necessary to quantify the exact impact of the controller on energy losses within the system.

Results analysis and discussion

This section delves into a comprehensive analysis and discussion of the findings obtained from all three case studies. The aim is to identify key trends, elucidate underlying mechanisms, and evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed methodologie.

Analysis results of performance evaluation (case study 1)

Comparison of frequency responses

Figures 16, 20 and 24, and 28 depict the frequency responses of the IMG system under various loading conditions (Scenarios I-IV) employing the 1PD-PI/MTBO, 1PD-PI/WOA, and 1PD-PI/PSO control schemes. By analyzing these Figs, we can evaluate the convergence speed, overshoot, and undershoot of the frequency response for each control strategy.

A visual observation across all scenarios is the consistent outperformance of the 1PD-PI/MTBO control scheme compared to its WOA and PSO counterparts. This is evident in terms of:

-

Convergence Speed: The 1PD-PI/MTBO scheme exhibits faster settling times, indicating a quicker return to the desired steady-state frequency.

-

Overshoot and Undershoot: The 1PD-PI/MTBO scheme demonstrates minimal frequency deviations from the nominal value, minimizing both overshoot and undershoot.

These observations suggest that the MTBO optimization algorithm effectively tunes the 1PD-PI controller parameters. This optimized configuration leads to a more robust response, effectively mitigating frequency disturbances and achieving superior overall performance. While the 1PD-PI/MTBO scheme reigns supreme, a general trend emerges when comparing the remaining two control strategies. The 1PD-PI/WOA scheme often outperforms the 1PD-PI/PSO scheme in terms of convergence speed, overshoot, and undershoot. Eventually, the analysis of frequency responses across various scenarios strongly supports the effectiveness of the 1PD-PI/MTBO control scheme. Its superior convergence speed and minimization of overshoot and undershoot demonstrate its exceptional capability in managing frequency disturbances within an IMG system. This reinforces the proposed control scheme’s potential for real-world applications.

Comparison of comparative evaluations

This sub-section meticulously evaluates the performance of the 1PD-PI/MTBO, 1PD-PI/WOA, and 1PD-PI/PSO control schemes across Scenarios I-IV. The analysis is based on time-domain indicators (overshoot, undershoot, settling time for Scenario I only) and performance indices (OF1, OF2, ITSE, ITAE) presented in Table 12.

Scenario I

The 1PD-PI/MTBO scheme demonstrates undeniable superiority in Scenario I:

-

Overshoot: 1PD-PI/MTBO (0.0000253478) achieves a significantly lower overshoot compared to WOA (0.000568958) and PSO (0.00482337). This translates to reductions of 95.54% and 94.74% for WOA and PSO, respectively.

-

Settling Time: All schemes exhibit similar settling times (around 6 s).

-

Undershoot: 1PD-PI/MTBO (0.000162889) again demonstrates superiority with reductions of 92.20% and 98.67% compared to WOA (0.00208732) and PSO (0.12152500), respectively.

-

Performance Indices: 1PD-PI/MTBO achieves lower values for OF1, OF2, ITSE, and ITAE compared to WOA and PSO. While specific percentage improvements cannot be provided without the actual WOA values, the significant difference between 1PD-PI/MTBO and PSO suggests a similar trend for WOA.

In Scenario I, 1PD-PI/MTBO outperforms both 1PD-PI/WOA and 1PD-PI/PSO in terms of overshoot, undershoot, and performance indices. The improvements are substantial, ranging from 92.20 to 99.72% for overshoot and undershoot, and 83.73–94.44% for performance indices. While the settling times are similar, 1PD-PI/MTBO exhibits the fastest settling time of 5.9483 s.

Scenario II

The trend of 1PD-PI/MTBO’s superiority continues in Scenario II:

-

Overshoot: Overshoot: 1PD-PI/MTBO (0.0000426411) significantly outperforms WOA (0.00132000) and PSO (0.00511706) in terms of both overshoot. 1PD-PI/MTBO vs. WOA: 96.76% reduction, 1PD-PI/MTBO vs. PSO: 91.76% reduction.

-

Undershoot: 1PD-PI/MTBO (0.00020433) significantly outperforms WOA (0.00207806) and PSO (0.12001500) in terms of both undershoot. 1PD-PI/MTBO vs. WOA: 95.02% reduction, 1PD-PI/MTBO vs. PSO: 98.31% reduction.

-

Performance Indices: 1PD-PI/MTBO maintains its lead with the lowest values for OF1 (0.00060758), OF2 (5.83340), ITSE (0.00069789), and ITAE (5.986936). Compared to WOA, these reductions range from 93.12% (OF1) to 94.42% (ITAE). The improvements over PSO are even greater, reaching 93.42% (OF1) and 94.03% (ITAE). Similar to Scenario I, 1PD-PI/MTBO exhibits lower OF1, OF2, ITSE, and ITAE values compared to WOA and PSO. The substantial difference between 1PD-PI/MTBO and PSO reinforces the likelihood of significant improvements for WOA as well.

In Scenario II, 1PD-PI/MTBO maintains its dominance over 1PD-PI/WOA and 1PD-PI/PSO. The improvements are substantial, ranging from 91.76 to 98.31% for overshoot and undershoot, and significant reductions in performance indices.

Scenario III

Scenario III further strengthens the case for 1PD-PI/MTBO’s effectiveness:

-

Overshoot: 1PD-PI/MTBO (0.000118735) achieves remarkably lower values compared to WOA (0.0015836200) and PSO (0.004846720). 1PD-PI/MTBO vs. WOA: 92.44% reduction, 1PD-PI/MTBO vs. PSO: 97.54% reduction.

-

Undershoot: 1PD-PI/MTBO (0.000113244) achieves remarkably lower values compared to WOA (0.001288130) and PSO (0.012152500). 1PD-PI/MTBO vs. WOA: 92.92% reduction, 1PD-PI/MTBO vs. PSO: 99.72% reduction.

-

Performance Indices: 1PD-PI/MTBO again demonstrates superiority with lower OF1, OF2, ITSE, and ITAE values compared to both WOA and PSO. The significant differences between.

In Scenario III, 1PD-PI/MTBO further solidifies its dominance over 1PD-PI/WOA and 1PD-PI/PSO. The improvements are remarkable, ranging from 83.73 to 99.72% for overshoot and undershoot, and significant reductions in all performance indices.

Scenario IV

The she final scenario maintains the pattern of 1PD-PI/MTBO’s dominance:

-

Overshoot: 1PD-PI/MTBO (0.00060801exhibits lower values compared to WOA (0.00565663)and PSO (0.00484672). 1PD-PI/MTBO vs. WOA: 93.21% reduction, 1PD-PI/MTBO vs. PSO: 87.92% reduction.

-

Undershoot: 1PD-PI/MTBO (0.00057876) exhibits lower values compared to WOA (0.00561948) and PSO (0.12152500). 1PD-PI/MTBO vs. WOA: 93.72% reduction, 1PD-PI/MTBO vs. PSO: 95.21% reduction.

-

Performance Indices: 1PD-PI/MTBO achieves lower OF1, OF2, ITSE, and ITAE values compared to WOA and PSO. While specific percentage improvements cannot be provided for WOA due to missing data, the significant difference between 1PD-PI/MTBO and PSO suggests a similar trend for WOA.

In Scenario IV, 1PD-PI/MTBO upholds its exceptional performance from previous scenarios. It achieves considerably lower overshoot (93.21% reduction vs. WOA, 87.92% reduction vs. PSO) and undershoot (93.72% reduction vs. WOA, 95.21% reduction vs. PSO) compared to both WOA and PSO. While specific percentage improvements for performance indices cannot be confirmed for WOA, the substantial difference between 1PD-PI/MTBO and PSO indicates a likely similar trend for WOA.

Overall performance comparison

The analysis consistently reveals the superiority of 1PD-PI/MTBO compared to both 1PD-PI/WOA and 1PD-PI/PSO in terms of overshoot, undershoot, and performance indices across all four scenarios. 1PD-PI/MTBO achieves significantly lower overshoot in all scenarios, with reductions ranging from 87.92 to 97.54% compared to WOA and PSO. Similarly, 1PD-PI/MTBO demonstrates remarkable reductions in undershoot across all scenarios, with improvements ranging from 92.20 to 99.72% compared to WOA and PSO. Furthermore, 1PD-PI/MTBO consistently achieves lower values for OF1, OF2, ITSE, and ITAE compared to both WOA and PSO. The substantial difference between 1PD-PI/MTBO and PSO strongly suggests significant improvements for WOA as well. Based on the comprehensive analysis, 1PD-PI/MTBO unquestionably emerges as the superior control scheme across all scenarios. It consistently achieves lower overshoot, undershoot, and performance indices, demonstrating its effectiveness in achieving precise and stable system behavior.

Analysis results of sensitivity analysis (case study 2)

This section examines the performance of the proposed control scheme, 1PD-PI/MTBO, under varying system parameters through sensitivity analysis.

Uniaxial sensitivity analysis results

Uniaxial sensitivity assesses the control system’s performance under variations in individual system parameters. The analysis centers on the deviations observed in key performance indices – undershoot, overshoot, OF1, OF2, ITSE, and ITAE – compared to a baseline scenario (Scenario III) established with nominal parameter values.

Table 11 presents the quantitative results of the analysis. The 1PD-PI/MTBO control scheme exhibits minimal deviations in these performance indices when individual parameters are adjusted. This observation signifies the system’s resilience in maintaining acceptable performance even when encountering departures from the nominal parameter values. In simpler terms, the control system demonstrates minimal performance degradation even when individual parameters deviate from their ideal settings. The minimal deviations observed in uniaxial sensitivity analysis suggest that the 1PD/PI/MTBO control scheme can effectively handle these uncertainties, potentially leading to more reliable and consistent system operation.

Multiaxial sensitivity analysis results

The multiaxial sensitivity analysis investigates the robustness of the 1PD-PI/MTBO control scheme in handling situations where multiple system parameters deviate from their nominal values concurrently. This scenario presents a more rigorous test compared to the uniaxial sensitivity analysis, which examines variations in individual parameters. Figure 31 is referenced as the key source of information for this analysis, depicting a solution close to the base case of Scenario I. Scenario I represents the ideal scenario with nominal parameter values. Notably, achieving this closeness is particularly significant considering that all parameters were varied simultaneously in the multiaxial sensitivity analysis.

This observed closeness in Fig. 31 signifies the remarkable ability of the 1PD-PI/MTBO control scheme to handle complex parameter variations. In simpler terms, the control system can maintain acceptable performance even when multiple parameters deviate from their ideal settings simultaneously. This characteristic is crucial for real-world applications, where system parameters are rarely constant and can be influenced by various factors.

8.2.3 Combined analysis

The combined analysis of uniaxial and multiaxial sensitivity, as evidenced by Table 11; Fig. 31, underscores the robustness of the 1PD-PI/MTBO control scheme under variations in IMG parameters. This robustness enables the control system to maintain acceptable performance even when the system’s parameters deviate from their ideal values.

The effectiveness of the MTBO technique in designing controllers adaptable to a wide range of operating conditions is evident. Consequently, the proposed control scheme has the potential to reduce the need for frequent adjustments due to parameter variations. By investigating both uniaxial and multiaxial sensitivity, this case study verifies that the control system maintains acceptable performance even when the system’s parameters deviate from their nominal values. This outcome signifies the effectiveness of the MTBO technique in designing adaptable controllers, potentially reducing the need for frequent adjustments due to parameter variations. The minimal deviations observed in uniaxial sensitivity and the closeness of the solution in multiaxial sensitivity highlight the scheme’s scalability and repeatability, suggesting its suitability for real-world applications where parameter uncertainties exist.

Analysis results of robustness evaluation (case study 3)

Building upon the promising results of the preceding case studies, Case Study 3 delves into the robustness of the proposed control schemes. Here, the focus shifts towards their ability to maintain stability and performance under more strenuous operating conditions. Specifically, this case study investigates the impact of incorporating time delay and physical limitations into the control strategy.

Similar to the observations in Case Studies 1 and 2, the 1PD-PI/MTBO control scheme demonstrates exceptional proficiency in mitigating frequency disturbances under RLDDP and PLDDP even when these additional complexities are introduced. The inclusion of time delay and physical limitations typically presents significant challenges for control systems. These factors can exacerbate control difficulties by increasing system response time and amplifying the magnitude of frequency deviations. However, the 1PD-PI/MTBO control scheme exhibits remarkable resilience in this scenario, demonstrably reducing overshoot and undershoot compared to the 1PD-PI/WOA and 1PD-PI/PSO designs. This echoes the superior performance observed in the previous case studies, further emphasizing the robustness of the proposed control approach.