Abstract

Increased propulsion force (PF) in the paretic limb is associated with improved walking speed in patients with stroke. However, late braking force (LBF), an additional braking force occurring between PF onset and toe-off, is present in a subset of stroke patients. Few studies have investigated the changes in LBF and walking speed in these patients. This study aimed to elucidate the patterns of change in PF and LBF during fast gait in hemiplegics and identify potential compensatory strategies based on the LBF patterns. Data from 100 patients with stroke walking at both comfortable (mean, 0.79 ± 024 m/s) and fast speeds (mean, 1.06 ± 0.35 m/s) were analyzed retrospectively stroke using a 3D motion analyzer. PF was higher during fast-speed walking than that during comfortable-speed walking in all patients, while LBF showed both decreasing and increasing trends during fast-speed walking. In the LBF increasing pattern, a reduction in in-phase coordination of the shank and foot during the pre-swing phase was observed, along with an increase in pelvic hike during fast-speed walking compared to those in the decreasing LBF pattern. Our findings demonstrate that alterations in LBF patterns are associated with gait deviations in patients with stroke at fast speeds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The life space of stroke patients is impacted by their walking speed1,2,3, underscoring the importance of training to enhance this aspect to improve community participation and overall quality of life4,5.

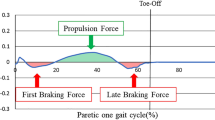

Propulsion force (PF), occurring in the latter portion of the stance phase of the affected lower limb, demonstrates a direct correlation with walking speed6,7. Recent studies focusing on gait among stroke patients have recognized PF during the late stance phase of the paretic side as a pivotal endpoint, with numerous intervention studies highlighting its role in enhancing walking speed8,9. Conversely, stroke patients tend to exhibit the manifestation of the posterior component of ground reaction force (GRF) just before toe-off10. This component, observed during the late stance phase, is termed late braking force (LBF), contrasting with the initial braking force observed in the early stance phase11.

We previously identified LBF in 110 out of 157 stroke patients and found that without the influence of PF, LBF was associated not only with the knee joint flexion angle in the pre-swing and swing phases of the affected limbs but also with walking speed12. We identified the following indicators related to LBF: trailing limb angle (TLA), in-phase coordination between the shank and foot on the affected side during the pre-swing phase (coordinated anterior tilt of the lower leg and plantar flexion of the foot), and reverse-phase coordination between the bilateral hips (coordinated hip flexion in the rear leg and hip extension in the front leg)12. Therefore, we believe that interventions aimed at improving gait in stroke patients should consider not only an increase in PF but also a decrease in LBF. Furthermore, studies should focus on the TLA on the paretic side, coordination between the shank and the foot, and bilateral hip coordination.

Previous research has indicated that stroke patients possess adaptable reserve capacity despite diminished PF resulting from lower limb paralysis13. This adaptability has been demonstrated in studies involving fast-paced gait conditions7,14,15. Furthermore, walking at an increased speed suggests improved kinematic gait for patients with stroke, including increased stride length, decreased bilateral asymmetry, and improved knee joint flexion angle during the swing phase6,14,16,17. While some reports suggest that the characteristic deviant gait of stroke patients, such as pelvic hike and circumduction during the swing phase, does not worsen under fast speed conditions14,18, others report increased hip circumduction with increased walking speed and a slight increase in pelvic hike compared to healthy controls11,16. Therefore, a more detailed analysis is needed regarding the changes in the characteristic deviant gait of stroke patients caused by increased walking speed.

In addition, the impact of fast-paced walking on LBF in hemiplegics remains unclear. Understanding how LBF is influenced during high-speed gait may unveil strategies to assist hemiplegics in performing optimally at such velocities, particularly if changes in LBF are not solely tied to alterations in PF.

This study aimed to elucidate the patterns of change in PF and LBF during fast gait in hemiplegics and to identify potential compensatory strategies based on the LBF pattern. We hypothesized that the pattern of change characterized by an increase or decrease in LBF would lead to differences in walking speed, stride length, and locomotor strategy during the swing phase in this population.

Methods

Participants

Ethical approval

for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Seiai Rehabilitation Hospital and the Graduate Schools of Toyo University (approval number: 20–244, 2022–12 S). Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study, and adherence to the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki was ensured.

This cohort investigation focused on stroke patients who underwent comprehensive gait analysis utilizing a motion analysis system (VICON-MX cameras: Vicon Motion System Ltd., Oxford, UK) at Seiai Rehabilitation Hospital in Fukuoka, Japan, spanning from 2017 to 2023.

The inclusion criteria comprised sub-acute stroke patients admitted to the rehabilitation unit, aged > 20 years, with supratentorial stroke, unilateral lower limb paresis, intact cognitive function, and the ability to comprehend instructions for gait analysis. Eligible patients were also required to walk independently at self-selected and maximum speeds without assistance or aids.

Exclusion criteria encompassed individuals with bilateral strokes, prior neurological or musculoskeletal conditions unrelated to stroke, and cases lacking documented PF necessary for determining LBF intervals.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

Patient demographics were meticulously documented at the time of gait analysis, encompassing age, sex, height, weight, time since stroke onset, stroke classification (hemorrhagic or ischemic), and the affected hemisphere. Clinical characteristics mirrored those of previous studies12, utilizing the total score, lower extremity motor score, and balance score of the Fugl-Meyer Assessment (FMA)19,20, the trunk control test (TCT) for trunk function assessment21, and the Functional Ambulation Category (FAC) for evaluating walking independence22.

Experimental conditions

The participants were instructed to walk along an 8 m walkway, completing two tasks: walking at a self-selected comfortable speed and walking as fast as possible. Two or three walking cycles were employed during the middle of each gait measurement to avoid a start/end step in the 8 m walking path. Therefore, 3–5 gait measurements were performed per patient for each condition. All participants walked independently, without the use of any ambulatory aids, such as canes or orthotic devices. A therapist accompanied them during gait measurements to prevent falls.

Experimental setup

Data collection utilized fourteen VICON-MX cameras (Vicon Motion System Ltd., Oxford, UK) and six force plates (600 × 400 mm; Advanced Mechanical Technology Inc., Watertown, MA, USA) operating at sampling frequencies of 100 Hz and 1000 Hz, respectively. The experimental walking path spanned 8 m with a measurement section of 6 m and an approach section of 2 m. Based on the Helen Hayes Marker Set, 29 reflective markers were affixed to participants’ bodies, including one at the sacrum’s center as an additional marker for the pelvis.

Data analysis

Data analysis employed Visual3D analytical software (C-Motion Ltd., Rochelle, IL, USA). Low-pass filters with cutoff frequencies of 6 Hz for spatial coordinates of reflective markers and 18 Hz for the GRF data were applied. Triaxial joint angles, lower extremity angular velocity, lower extremity joint moments, GRF, and center of pressure (COP) were calculated. Joint moment and GRF data were normalized to participants’ body weight.

Using the vertical component of the GRF, a gait cycle was divided into four phases: loading response, single-leg support, pre-swing, and swing. Loading response was defined as the initial contact of the paretic lower limb to the toe-off of the non-paretic lower limb, single-leg support was defined as the toe-off of the non-paretic lower limb to the initial contact of the non-paretic lower limb, pre-swing was defined as the initial contact of the non-paretic lower limb to the toe-off of the paretic lower limb, and swing was from the toe-off of the paretic lower limb to the initial contact of the paretic lower limb.

A threshold for the vertical GRF was set at 1% of body weight, following the methodology of a previous study11,12. Consistent with previous studies11,12, PF and LBF were normalized to 100% of the gait cycle of the paretic lower limb, with the forward component post-loading response phase defined as PF and the backward component as LBF. PF and LBF impulses, representing time integrals of PF and LBF, were calculated as described in previous studies (Fig. 1)11,12,13. The kinetic and kinematic parameters affecting PF and LBF were based on prior research, including TLA, in-phase coordination between the shank and foot, and reverse-phase coordination between the bilateral hip joints during the pre-swing phase on the paretic side12). TLA was evaluated by measuring the angle formed between a line perpendicular to the floor from the greater trochanter and another line extending from the greater trochanter to the COP of the hind limb15,23,24,25. Coordination among the shank, foot, and bilateral hip joints was calculated using the root mean square (RMS) of the continuous relative phase (CRP) between the segments in the pre-swing phase (CRP-RMS). Following methods from previous studies12,26,27,28, the CRP-RMS calculates the phase angles from the normalized angular velocities of each segment, and the phase difference between the phase angles is calculated using the RMS during the pre-swing phase segment. This study focused on the coordination of the paretic side’s shank and foot as well as both thighs because in-phase coordination of the shank and foot on the paretic side and reverse-phase coordination of the bilateral thighs are involved in the development of LBF12.

Definitions of propulsion force and late braking force. (a) The forward component of the GRF after the loading response phase is defined as the propulsion force. (b) The backward component of the GRF after the propulsion force is defined as the late braking force. (c) The AGRF of typical cases in which the LBF appears. GRF, ground reaction force; AGRF, anterior ground reaction force.

Calculated spatiotemporal gait metrics included walking velocity, step length for the paretic limb, step length for the non-paretic limb, and the maximum knee flexion angles of the paretic limb during the pre-swing and swing phases. Additionally, pelvic hike and hip circumduction, common deviation gait observed in stroke patients14,16,29,30,31, were assessed. Pelvic hike was determined from the pelvic angle, while the maximum hip circumduction was derived from the hip abduction angle. Furthermore, the ratios of spatiotemporal and kinematic gait parameters between fast-speed walking and comfortable-speed walking were calculated (ratio = fast speed condition / comfortable speed condition).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics Ver. 28 (International Business Machines Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and Python (3.10.12). The mean value of the five gait cycles of the paretic limb was utilized for all gait analysis data. The normality of each parameter was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, with significance set at a p-value of < 0.05.

Initially, comparisons of spatiotemporal and kinematic gait parameters between walking at a comfortable speed and walking at a fast speed were made using paired-sample t-tests or Wilcoxon nonparametric tests. Secondly, the anteroposterior component of GRF, knee angle, pelvic hike, and hip circumduction were evaluated using statistical parameter mapping (SPM) with the SPM1d code (spm1d-0.4.32-py3) to compare differences between comfortable speed walking and fast speed walking in a time series of data for a single walking cycle. Thirdly the analysis focused on the change in LBF with speed modulation from comfortable to fast speed. Participants were classified into three groups: those without LBF at either comfortable or fast speeds (without LBF group), those with decreased LBF at fast speed compared to comfortable speed (decreased LBF group), and those with increased LBF at fast speed compared to comfortable speed (increased LBF group). A one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction was employed to analyze the rate of change in spatiotemporal and kinematic gait parameters across these three groups. When equal variances were assumed, Bonferroni’s method was used; when equal variances were not assumed, Games–Howell’s method was used for the post-hoc analysis. In addition, clinical characteristics, such as age, FMA lower limb motor and balance scores, and trunk control test, were compared between the groups. As clinical characteristics outside of age are ordinal measures, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used.

Results

Out of a total of 462 stroke patients who underwent gait analysis during the study period, 100 met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled. Table 1 presents the basic demographics and clinical characteristics of the patients. The participants comprised subacute cases during hospitalization, with a mean FMA lower extremity motor score of 29.4 points (range: 16–34 points). Among them, 10 patients were classified as FAC III, 39 as FAC IV, and 51 as FAC IV, indicating that 90% were walking independently.

Table 2 compares the spatiotemporal and kinematic parameters for walking at comfortable and fast speeds. All parameters were verified for normal distribution. Most parameters increased significantly during fast-speed walking (p < 0.001). Specifically, walking speed and PF increased in all patients, with overall increases of 34% and 24%, respectively. However, pelvic hike, hip circumduction, LBF, and coordination between the shank and foot did not show significant changes (p = 0.934, p = 0.627, p = 0.861, p = 0.118).

Figure 2 shows statistical parametric mapping results of the time series data. For the anterior-posterior component of GRF, PF showed a statistically significant increase of 22–50% for fast-speed walking. Just before toe-off, the PF increased slightly for walking at a comfortable speed. Knee flexion angle showed a statistically significant increase of 42–79% for fast-speed walking. Regarding pelvic hike, the angle of elevation was greater for walking at a comfortable speed (73–83%). There was a significant difference in hip adduction/abduction angles (19–63%); however, abduction was greater for fast-speed walking (60%).

Statistical parametric mapping results for A: anterior-posterior component of GRF, B: knee joint flexion/extension angle, C: pelvic hike/down control angle, and D: hip abduction/adduction angle. The upper panel shows the mean curve and standard deviation for comfortable speed walking (solid line) and fast speed walking (dashed line). The lower panel displays the SPM (t) curves, with significant differences indicated in black.

The classification of groups based on changes in LBF is depicted in Fig. 3.

At a comfortable walking speed, 39 patients exhibited without LBF, while 61 had LBF. Subsequently, at faster speeds, 30 patients maintained without LBF, 36 experienced a decrease in LBF, and 34 had an increase in LBF.

Table 3 presents a comparison of the ratio of changes in spatiotemporal to kinematic parameters for each group relative to changes in LBF. Normal distribution for each parameter was confirmed for all groups. All groups demonstrated increases in gait speed, stride length, knee flexion angle in the pre-swing and swing phases, PF, TLA, and reverse-phase coordination of bilateral thighs, with no significant differences among the groups (p > 0.05). However, the group with increased LBF exhibited significantly more pelvic hike compared to those without LBF (p < 0.001) and less in-phase coordination of the shank and foot compared to both the without LBF and increased LBF groups (p < 0.001 and p = 0.034, respectively).

Table 4 compares the clinical characteristics between the groups. No significant differences were found in age, FMA balance score, and trunk control test results between the three groups. However, the FMA lower limb movement score was significantly lower in the group with increased LBF compared to the group with without LBF (p < 0.05).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the patterns of change in PF and LBF in stroke patients as they transition from walking at a comfortable speed to walking at a fast speed and to elucidate the motor strategies involved in walking based on these patterns of LBF change. We analyzed gait measurement data from 100 stroke patients who met the criteria associated with changes in walking speed. The results revealed that while PF increased in all patients, there were both decreasing and increasing patterns of LBF noted, with some patients exhibiting without LBF during comfortable speed walking but experiencing LBF during maximal speed walking, confirming our hypothesis.

Interestingly, although there were no differences observed between patterns of LBF change concerning gait speed, stride length, or the ratio of change in knee flexion angle, the patterns with increasing LBF clearly demonstrated variances in motor strategies, such as increased pelvic hike during the swing phase, compared to patterns with decreasing LBF.

Effects of changes in walking speed on each parameter

In this study, a comparative analysis was conducted between walking at the subject’s comfortable speed and the fastest speed attainable. Similar to previous studies, wherein walking speed increased by an average of 39.6% (range: 27.9–55.8%)6,7,32,33,34,35, our study observed an average increase in walking speed of 34.2%, consistent with prior reports.

Furthermore, both the paretic and non-paretic sides showed significant increases in stride length, knee joint flexion angle during the pre-swing phase and the swing phase, PF (directly related to gait speed), and TLA (significantly related to PF). Although pelvic hike did not differ significantly at the maximum value during the swing phase, SPM1d showed a lower angle of elevation at the fastest speed gait in the middle swing phase. This may be due to variations in the timing of peak pelvic hikes; however, in general, the pelvic hike did not increase with increasing speed. Although there was no significant difference in hip circumduction at the maximum value, the hip abduction angle was greater at the initial swing of walking at the fastest speed in SPM1d. However, there was no significant difference in hip abduction angle in the middle swing phase, when the hip abduction angle peaked, suggesting no increase in circumduction with increasing speed. These results support previous findings of no worsening of deviant gait patterns during the swing phase6,14,16,17.

However, unlike PF, which increased in all patients as walking speed increased, changes in LBF with increasing walking speed have yet been previously fully examined. In the present study, LBF, in contrast to PF, did not significantly change with increasing speed, indicating that it may be a feature independent of speed modulation. This result differs from that reported by Dean et al.,11 but may be due to the wider range of lower extremity dysfunction in the participants in our study than in their study and the different measurement conditions on the treadmill and ground.

Coordination of bilateral thighs was significantly increased in fast-speed walking. The CRP_RMS used in this analysis is interpreted as increased in-phase coordination when it is close to 0°, and increased reverse-phase coordination when it is close to 180°26,27.

In stroke patients, heightened hip flexor activity in the paretic limb is observed as a strategy to enhance walking speed33,36. This could lead to an augmented reverse-phase coordination of the bilateral thighs during the pre-swing phase. Gait practice using an exoskeletal robot for the bilateral lower limbs improves bilateral hip joint coordination37,38. Therefore, future studies should explore whether repeated fast-speed walking can improve bilateral hip joint coordination, as in an intervention study using an exoskeletal robot.

On the other hand, no notable changes were detected in shank and foot coordination, another factor influencing LBF. Hutin et al.26 reported an escalation in in-phase coordination of the shank and foot during the late stance phase (50–60% of the gait cycle) at fast speeds compared to comfortable speeds; however, our study’s findings do not align with this observation. This discrepancy may arise from differences in extraction methods compared to the previous study, as well as variations in patient age range and post-onset period. Consequently, we posit that LBF did not decrease with velocity due to the lack of change in shank and foot coordination, despite increases in TLA and reverse-phase coordination of the bilateral thighs.

Comparison of each parameter ratio according to the pattern of change in LBF

The patterns of change in LBF with different gait speeds were classified into three categories: without LBF at both comfortable and fast speeds, decreasing LBF, and increasing LBF. Of the 61 patients with LBF at comfortable speeds, 36 showed a decrease in LBF at fast speeds (13 patients changed to without LBF), 34 exhibited an increase in LBF at fast speeds and of these, 9 patients who did not exhibit LBF at comfortable speeds exhibited LBF at the fastest speeds. Therefore, we included patients without LBF and compared the clinical characteristics and rate of change in parameters of fast speed relative to comfortable speed.

Comparison of clinical characteristics showed no differences among the three groups with respect to age, balance ability, and trunk function. The group with increased LBF had poorer lower limb motor function than the group without LBF; however, there was no difference in lower limb motor function between the group with decreased LBF and the group with increased LBF. Therefore, it is unclear whether differences in motor function are responsible for the increase or decrease in LBF associated with increased walking speed.

Furthermore, the three patterns showed no significant differences in walking speed, stride length, knee joint flexion angle between the pre-swing phase and swing phases, or hip circumduction. However, pelvic hike was significantly increased in the pattern with increased LBF compared to the other two patterns. This result differs from previous reports that do not show increased deviatoric movements, such as pelvic hike, as an exercise strategy to increase walking speed14,16. It indicates that walking at a fast speed is not suitable for all patients. Generally, pelvic hikes are seen as a compensatory measure to ensure toe clearance during the swing phase29,30,39. In this study, the group with the increased LBF pattern also had an increased knee flexion angle similar to that of the other groups. However, the increased LBF despite the fast-speed condition may have compensated for the delay in toe-off.

Next, the pattern of increased LBF was associated with decreased coordination between the shank and foot, whereas the other groups exhibited increased coordination. Specifically, only the group with increased LBF showed a decrease in in-phase coordination, while the other two groups showed an increase. Additionally, the group with decreasing LBF showed a significantly higher ratio of change in PF compared to the group with increasing LBF. This suggests that without the potential to increase in-phase coordination between the shank and foot, there is less increase in PF and more increase in LBF. This observation is analogous to the presence of cases in which the potential is realized in fast speed gait, similar to the study that reported that many patients with stroke have latent plantar flexor muscles on the paretic side that cannot be voluntarily exerted40. Contrarily, when the patient’s plantar flexor potential is low or when the patient has a condition that may inhibit it, it may be difficult to improve shank-foot coordination, similar to the studies that reported that reduced central drive to the plantar flexor muscles reduces PF and spasticity of the plantar flexors, thereby inhibiting improvement in gait speed and spatial asymmetry32,40,41,42. These results suggest that it may be difficult to improve shank-foot coordination with increased gait speed if the patient has low potential plantar flexor muscle strength or a disease that inhibits it.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is that we did not measure muscle activity; therefore, we were unable to verify the extent of cortical nerve input in the paretic lower extremity and its relevance, such as simultaneous contractions. This can be confirmed in future studies by using additional data measurements. Additionally, it is possible that a more suitable walking speed could have been determined by grading the rate of increase in suitable walking speed; however, this was not feasible in this retrospective study design. Another limitation is the classification of groups into three categories: without LBF/increased LBF/decreased LBF. It should be noted that detailed patterns exist, such as cases where LBF is absent at comfortable speeds but present at fast speeds, or vice versa. The LBF impulses used in the classification were averaged over five gait cycles, and because LBF occurred irregularly, these characteristics should be taken into account in future studies for further validation.

Conclusions

This study provides detailed insights into the variations of PF and LBF in stroke patients across different walking speeds. PF consistently increased with higher speeds, while LBF exhibited both increasing and decreasing patterns. An increased LBF pattern was associated with an elevated pelvic hike, suggesting its significance during fast-paced walking. Enhancing PF and reducing LBF during fast walking necessitates the ability to perform anterior tilt of the shank and plantar flexion of the foot during the pre-swing phase. Moving forward, there is a need to explore the development of gait tasks and supportive tools that effectively promote decreased LBF and increased PF.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Perry, J., Garrett, M., Gronley, J. K. & Mulroy, S. J. Classification of walking handicap in the stroke population. Stroke. 26, 982–989 (1995).

Mulder, M., Nijland, R. H., van de Port, I. G., van Wegen, E. E. & Kwakkel, G. Prospectively classifying community walkers after stroke: who are they? Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 100, 2113–2118 (2019).

Fulk, G. D., Reynolds, C., Mondal, S. & Deutsch, J. E. Predicting home and community walking activity in people with stroke. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 91, 1582–1586 (2010).

Schmid, A. et al. Improvements in speed-based gait classifications are meaningful. Stroke. 38, 2096–2100 (2007).

Grau-Pellicer, M., Chamarro-Lusar, A. & Medina-Casanovas, J. Serdà Ferrer, C. walking speed as a predictor of community mobility and quality of life after stroke. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 26, 349–358 (2019).

Hsiao, H., Awad, L. N., Palmer, J. A., Higginson, J. S. & Binder-Macleod, S. A. Contribution of Paretic and Nonparetic Limb Peak Propulsive Forces to changes in walking speed in individuals Poststroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair.30, 743–752 (2016).

Beaman, C. B., Peterson, C. L., Neptune, R. R. & Kautz, S. A. Differences in self-selected and fastest-comfortable walking in post-stroke hemiparetic persons. Gait Posture. 31, 311–316 (2010).

Alingh, G. & Van, A. Effectiveness of rehabilitation interventions to improve paretic propulsion in individuals with stroke–A systematic review. Clin. Biomed. Res.71, 176–188 (2020).

Alingh, J. F., Groen, B. E., Kamphuis, J. F., Geurts, A. C. H. & Weerdesteyn, V. Task-specific training for improving propulsion symmetry and gait speed in people in the chronic phase after stroke: a proof-of-concept study. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 18, 69 (2021).

Turns, L. J., Neptune, R. R. & Kautz, S. A. Relationships between muscle activity and anteroposterior ground reaction forces in hemiparetic walking. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 88, 1127–1135 (2007).

Dean, J. C., Bowden, M. G., Kelly, A. L. & Kautz, S. A. Altered post-stroke propulsion is related to paretic swing phase kinematics. Clin. Biomech.72, 24–30 (2020).

Ohta, M., Tanabe, S., Katsuhira, J. & Tamari, M. Kinetic and kinematic parameters associated with late braking force and effects on gait performance of stroke patients. Sci. Rep.13, 7729 (2023).

Lewek, M. D., Raiti, C. & Doty, A. The Presence of a Paretic Propulsion Reserve during Gait in individuals following stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair.32, 1011–1019 (2018).

Tyrell, C. M., Roos, M. A., Rudolph, K. S. & Reisman, D. S. Influence of systematic increases in treadmill walking speed on gait kinematics after stroke. Phys. Ther.91, 392–403 (2011).

Hsiao, H., Knarr, B. A., Higginson, J. S. & Binder-Macleod, S. A. mechanisms to increase propulsive force for individuals poststroke. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 12, 40 (2015).

Kettlety, S. A., Finley, J. M., Reisman, D. S., Schweighofer, N. & Leech, K. A. Speed-dependent biomechanical changes vary across individual gait metrics post-stroke relative to neurotypical adults. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 20, 14 (2023).

Lamontagne, A. & Fung, J. Faster is better: implications for speed-intensive gait training after stroke. Stroke. 35, 2543–2548 (2004).

Jonkers, I., Delp, S. & Patten, C. Capacity to increase walking speed is limited by impaired hip and ankle power generation in lower functioning persons post-stroke. Gait Posture. 29, 129–137 (2009).

Meyer, F., Jääskö, A. R., Norlin, V. & L. & The post-stroke hemiplegic patient. II. Incidence, mortality, and vocational return in Göteborg, Sweden with a review of the literature. Scand. J. Rehabil Med.7, 73–83 (1975).

Danells, G. D. J., Black, S. E. & C. J. & The Fugl-Meyer assessment of motor recovery after stroke: a critical review of its measurement properties. Neurorehabil Neural Repair.16, 232–240 (2002).

Collin, C. & Wade, D. Assessing motor impairment after stroke: a pilot reliability study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 53, 576–579 (1990).

Holden, M. K., Gill, K. M., Magliozzi, M. R., Nathan, J. & Piehl-Baker, L. Clinical gait assessment in the neurologically impaired. Reliab. Meaningfulness Phys. Ther.64, 35–40 (1984).

Lewek, M. D. & Sawicki, G. S. Trailing limb angle is a surrogate for propulsive limb forces during walking post-stroke. Clin. Biomech.67, 115–118 (2019).

Awad, L. N., Binder-Macleod, S. A., Pohlig, R. T. & Reisman, D. S. Paretic Propulsion and Trailing Limb Angle are key determinants of Long-Distance walking function after stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair.29, 499–508 (2015).

Ray, N. T., Reisman, D. S. & Higginson, J. S. Combined user-driven treadmill control and functional electrical stimulation increases walking speeds poststroke. J. Biomech.124, 110480 (2021).

Hutin, E. et al. Walking velocity and lower limb coordination in hemiparesis. Gait Posture. 36, 205–211 (2012).

Sakuma, K. et al. Gait kinematics and physical function that most affect intralimb coordination in patients with stroke. NeuroRehabilitation. 45, 493–499 (2019).

Haddad, J. M., van Emmerik, R. E. A., Whittlesey, S. N. & Hamill, J. Adaptations in interlimb and intralimb coordination to asymmetrical loading in human walking. Gait Posture. 23, 429–434 (2006).

Stanhope, V. A., Knarr, B. A., Reisman, D. S. & Higginson, J. S. Frontal plane compensatory strategies associated with self-selected walking speed in individuals post-stroke. Clin. Biomech.29, 518–522 (2014).

Haruyama, K. et al. Pelvis-Toe Distance: 3-Dimensional gait characteristics of functional limb shortening in Hemiparetic Stroke. Sensors21, 5417 (2021).

Motoya, R. et al. Classification of abnormal gait patterns of poststroke hemiplegic patients in principal component analysis. Japanese J. Compr. Rehabilitation Sci.12, 70–77 (2021).

Palmer, J. A., Hsiao, H., Awad, L. N. & Binder-Macleod, S. A. Symmetry of corticomotor input to plantarflexors influences the propulsive strategy used to increase walking speed post-stroke. Clin. Neurophysiol.127, 1837–1844 (2016).

Jonsdottir, J. et al. Functional resources to increase gait speed in people with stroke: strategies adopted compared to healthy controls. Gait Posture. 29, 355–359 (2009).

Vive, S., Elam, C. & Bunketorp-Käll, L. Comfortable and maximum gait speed in individuals with chronic stroke and community-dwelling controls. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis.30, 106023 (2021).

Nascimento, L. R., de Menezes, K. K. P., Scianni, A. A. & Faria-Fortini, I. Teixeira-Salmela, L. F. Deficits in motor coordination of the paretic lower limb limit the ability to immediately increase walking speed in individuals with chronic stroke. Braz J. Phys. Ther.24, 496–502 (2020).

Milot, M. H., Nadeau, S. & Gravel, D. Muscular utilization of the plantarflexors, hip flexors and extensors in persons with hemiparesis walking at self-selected and maximal speeds. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol.17, 184–193 (2007).

Puentes, S. et al. Reshaping of bilateral gait coordination in hemiparetic stroke patients after early robotic intervention. Front. Neurosci.12, 719 (2018).

Pan, Y. T. et al. Effects of bilateral assistance for hemiparetic gait post-stroke using a powered hip exoskeleton. Ann. Biomed. Eng.51, 410–421 (2023).

Van Criekinge, T. et al. Associations between trunk and gait performance after stroke. Gait Posture. 57, 179–180 (2017).

Awad, L. N., Hsiao, H. & Binder-Macleod, S. A. Central drive to the paretic ankle plantarflexors affects the relationship between propulsion and walking speed after stroke. Neurol. Phys. Ther.44, 42–48 (2020).

Lin, P. Y., Yang, Y. R., Cheng, S. J. & Wang, R. Y. The relation between ankle impairments and gait velocity and symmetry in people with stroke. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 87, 562–568 (2006).

Yamada, T., Ohta, M. & Tamari, M. Effect of spasticity of the ankle plantar flexors on the walking speed of hemiplegic stroke patients after maximum walking speed exercises. Jpn J. Compr. Rehabil Sci.12, 64–69 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We extend our sincere gratitude to all the patients, Seiai Rehabilitation Hospital, and related parties for their invaluable cooperation in facilitating this research. We also acknowledge Editage (www.editage.jp) for providing English language editing services.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.O. and S.T. were responsible for data collection. All authors contributed to data analysis and interpretation. M.O. drafted the main manuscript text and prepared the figures and tables. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclosures

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (22K21261).

Additional information

O.M., J.K., and T.M. received research grants from JSPS KAKENHI. J.K. is an advisor and shareholder (unlisted) of Trunk Solution Co., Ltd., and obtains patent royalties. Trunk Solution Co. Ltd. was not included in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ohta, M., Tanabe, S., Tamari, M. et al. Patterns of change in propulsion force and late braking force in patients with stroke walking at comfortable and fast speeds. Sci Rep 14, 22316 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74093-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74093-1