Abstract

Adapting to different environments throughout daily activities requires flexibility in allocating attention. Compromised dual-tasking can hinder mobility, increase fall risk, and decrease functional independence in patients with essential tremor, who exhibit both mobility and cognitive impairments. We evaluated motor and cognitive dual-task effects and task prioritization in 15 people with Essential Tremor (ET) and 15 age-matched people without ET during a standard and more challenging water-carry TUG. Task-specific interference was evaluated by calculating motor and cognitive dual-task effects, whereas task prioritization was assessed by contrasting the cognitive dual-task effect with the motor dual-task effect. The simultaneous performance of two tasks did not differentially impact motor or cognitive performance in either group, and both groups prioritized cognitive task performance in standard and water-carry TUG assessments. This study enhances our understanding of motor-cognitive interactions in individuals with essential tremor. These insights could lead to patient-centered approaches to therapy to improve functional performance in dynamic daily environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Essential Tremor (ET) is perhaps the most common movement disorder1, impacting approximately 7 million people or 2.2% of the United States population alone1. ET has been defined by the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society as an isolated action tremor of bilateral upper limbs of at least 3 years duration2. While ET has classically been regarded as a monosymptomatic disorder, more recent studies have highlighted its walking3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 and cognitive deficits11,12,13,14. Dysfunction in these domains contributes independently to functional disability, particularly in elderly patients who take medications that act on tremors and other neurological symptoms. Therefore, a detailed examination of interactions among walking, balance, and cognition is warranted in patients with and without ET. Allocation of attentional resources critically influences walking, balance, and other aspects of motor performance, especially in patients with pre-existing physical or neurological deficits15,16. Simultaneously engaging in two or more tasks (i.e., dual-task performance) creates competition for limited attentional resources, and individuals may employ distinct strategies when their attention is divided17. Motor Dual-Task effects (motDTE) refer to changes in motor performance when a secondary cognitive task is introduced simultaneously, compared to when the motor task is executed in isolation17. Conversely, cognitive Dual-Task Effects (cogDTE) denote alterations in cognitive performance when a concurrent motor task is introduced relative to when the cognitive task is carried out alone17,18,19. Task prioritization describes interactions between motor and cognitive task performance in the dual-task context, such that more or less attentional resources might be devoted to either component20,21,22,23. Dual-task performance is highly relevant in daily life, as diminished capabilities in this domain can severely hinder functional mobility and community interactions24,25. Several studies have investigated dual-task performance in people with ET26,27. While insightful, the study designs did not include a single cognitive task condition and focused solely on examining the impact on motor performance. Therefore, examining the interaction between the two tasks when performed simultaneously and assessing prioritization strategies is impossible. Consideration of motor and cognitive task interaction is vital in a population such as ET with known walking and cognitive deficits. Further, these studies only examined dual-task performance during straight-line walking or quiet stance assessments26,27. Limited studies in ET have examined the association between motor and cognitive performance during postural transitional movements (i.e., TUG), which may reflect one’s ability to allocate attentional resources while performing more ecologically valid everyday activities24,25. Thus, considering dual-task performance during more complex activities that may reflect daily real-world scenarios is warranted. Therefore, this study aims to compare cognitive-motor interference via dual-task performance in people with and without Essential Tremor during both a standard and more complex water-carry TUG. Specifically, we will compare motor and cognitive dual-task performance between people with and without ET during both the standard and water-carry TUG assessments. Finally, we will compare task prioritization strategies across groups during the standard and water-carry TUG. Given recent evidence that people with versus without ET display significant walking and cognitive impairments14,28,29, we hypothesize that the ET group will exhibit increased motor and cognitive dual-task effects and that motor performance will be the prioritized adaptive strategy in people with ET.

Results

Mean and standard deviation data for cognitive-motor interference outcomes during standard and water-carry TUGs, along with the calculated DTE and task prioritization across ET and Non-ET groups are in Table 1. No significant group differences were observed for the ABC, FES, or cognitive assessments (Table 1).

Standard TUG- motor and cognitive dual task effect (motDTE and cogDTE)

Considering the motDTE during the standard TUG assessment, we found a significant main effect of group (F1,28 = 4.19, p = .05, ŋ2 = 0.13). People with ET took longer to complete the standard TUG regardless of whether it was accompanied with a concurrent cognitive task (Mdiff = 3.46, SE = 1.69, p = .05) (Fig. 1A, B). We also found a significant main effect of task, regardless of group; the standard TUG took longer to complete with the addition of the cognitive task compared to when the standard TUG was performed alone (F1,28 = 48.73, p < .001, ŋ2 = 0.64). There was no significant group X task interaction (F1,28 = 1.81, p = .19, ŋ2 = 0.06). Further, the comparison of motDTE between groups was not different (F1,28 = 0.027, p = .87), indicating that the addition of a secondary cognitive task did not differentially impact TUG performance in people with ET (Fig. 1C). Considering the cogDTE during the standard TUG assessment, we found no significant main effect of group (F1,26 = 0.027, p = .87, ŋ2 = 0.001) (Fig. 2A, B). There was a significant main effect of task (F1,26 = 16.531, p < .001, ŋ2 = 0.39). Regardless of group, participants provided more correct responses during the seated cognitive task compared to when they completed the cognitive task alongside the standard TUG (Mdiff = 1.89, SE = 0.47, p < .001). There was no significant group X task interaction (F1,26 = 0.477, p = .49, ŋ2 = 0.02). Further cogDTE was not different between groups (F1,24.9 = 0.345, p = .56), suggesting that dual-task performance did not differentially impact cognitive performance in people with ET compared to people without ET (Fig. 2C).

Change in motor task performance (TUG performance) from single to dual in the standard TUG assessment. (A) represents the mean TUG duration during the standard single-task TUG and the dual-task standard TUG in each group. (B) depicts individual data points. (C) depicts the motor dual-task effect during the standard TUG for each group. Blue bars represent the Non-Essential Tremor group, while orange bars represent the Essential Tremor group. Individual data points in each group are indicated by open-filled circles. DTE % = Dual Task Effect and was calculated as follows: ((Dual Task Performance – Single Task Performance) / Single Task Performance) *100. Therefore, positive values indicate facilitation that is improved performance (shorter TUG duration) in the dual-task condition compared to the single-task condition. Negative values indicate interference, that is, reduced performance (longer TUG duration) in the dual-task condition compared to the single-task condition.

Change in the cognitive task performance (verbal fluency task) during the standard TUG assessment. (A) The mean number of correct responses provided in the verbal fluency task during the standard single-task TUG and the dual-task standard TUG in each group. (B) depicts individual data points. (C) depicts the cognitive dual-task effect during the standard TUG for each group. Blue bars represent the Non-Essential Tremor group, while orange bars represent the Essential Tremor group. Individual data points in each group are indicated by open-filled circles. DTE % = Dual Task Effect and was calculated as follows: ((Dual Task Performance – Single Task Performance) / Single Task Performance) *100. Therefore, positive values indicate facilitation that is improved performance (more correct responses) in the dual-task condition compared to the single task condition. Negative values indicate interference, that is, reduced performance (fewer correct responses) in the dual-task condition compared to the single-task condition.

Water-Carry TUG- motor and cognitive dual task effect (motDTE and cogDTE)

Considering the motDTE during the water-carry TUG assessment, we found a significant main effect of group (F1,28 = 8.05, p = .008, ŋ2 = 0.22). People with ET took longer to complete the water-carry TUG regardless of whether it was accompanied with a concurrent cognitive task (Mdiff = 4.70, SE = 1.66, p = .008) (Fig. 3A, B). There was a significant main effect of task (F1,28 = 21.04, p < .001, ŋ2 = 0.43). Regardless of group, participants provided more correct responses during the seated cognitive task compared to during the Water-Carry TUG and verbal fluency task (Mdiff = 3.35, SE = 0.73, p < .001). There was no significant group X task interaction (F1,28 = 0.920, p = .35, ŋ2 = 0.03). The motDTE was also not different between people with and without ET (F1,25.9 = 0.203, p = .66). Hence, suggesting that dual-task performance during the water-carry TUG did not differentially impact TUG performance in people with ET compared to people without ET (Fig. 3C). Considering the cogDTE during the water-carry TUG assessment, we found no significant main effect of group (F1,26 = 0.082, p = .78, ŋ2 = 0.003) (Fig. 4A, B). There was a significant main effect of task (F1,26 = 12.17, p = .002, ŋ2 = 0.32). Regardless of group, participants provided more correct responses during the single cognitive task compared to during the Water-Carry TUG + cognitive task (Mdiff = 1.75, SE = 0.5, p = .002). There was no significant group X task interaction (F1,26 = 3.69, p = .06, ŋ2 = 0.12). Further, comparison of the cogDTE between groups revealed no significant differences (F1,25.2 = 4.05, p = .06), thereby suggesting that dual-task performance did not differentially impact cognitive performance in people with ET compared to people without ET (Fig. 4C).

Change in motor task performance (TUG performance) from single to dual in the water-carry TUG assessment. (A) represents the mean TUG duration during the water-carry single-task TUG and the dual-task water-carry TUG in each group. (B) depicts individual data points. (C) depicts the motor dual-task effect during the water-carry TUG for each group. Blue bars represent the Non-Essential Tremor group, while orange bars represent the Essential Tremor group. Individual data points in each group are indicated by open-filled circles. DTE % = Dual Task Effect and was calculated as follows: ((Dual Task Performance – Single Task Performance) / Single Task Performance) *100. Therefore, positive values indicate facilitation that is improved performance (shorter TUG duration) in the dual-task condition compared to the single-task condition. Negative values indicate interference, that is, reduced performance (longer TUG duration) in the dual-task condition compared to the single-task condition.

Change in the cognitive task performance (verbal fluency task) during the water-carry TUG assessment. (A) represents the mean number of correct responses provided in the verbal fluency task during the water-carry single-task TUG and the dual-task water-carry TUG in each group. (B) depicts individual data points. (C) depicts the cognitive dual-task effect during the water-carry TUG for each group. Blue bars represent the Non-Essential Tremor group, while orange bars represent the Essential Tremor group. Individual data points in each group are indicated by open-filled circles. DTE % = Dual Task Effect and was calculated as follows: ((Dual Task Performance – Single Task Performance) / Single Task Performance) *100. Therefore, positive values indicate facilitation that is improved performance (more correct responses) in the dual-task condition compared to the single task condition. Negative values indicate interference, that is, reduced performance (fewer correct responses) in the dual-task condition compared to the single-task condition.

Task prioritization

The one-way ANOVA comparing task prioritization between individuals with and without ET yielded non-significant results for both the standard TUG (F1,25.5 = 0.358, p = .55) (Fig. 5A) and the water-carry TUG (F1,26 = 0.806, p = .38) (Fig. 5B). In both assessments, both groups exhibited negative prioritization values, indicating cognitive prioritization, more attention allocated to cognitive task performance over motor task performance. However, there were no significant differences in the degree of cognitive prioritization between the groups during either the standard or water-carry TUG.

Task prioritization during the standard and water-carry TUG. (A) shows attention allocation strategy during the standard TUG assessment, while (B) displays attention allocation strategy during the water-carry TUG assessment. Blue bars represent the Non-Essential Tremor group, while orange bars represent the Essential Tremor group. Individual data points in each group are indicated by open-filled circles. Task prioritization was calculated using the following equation: motDTE – cogDTE. Therefore, positive values represent motor prioritization, while negative values depict cognitive prioritization.

Discussion

The study compared cognitive-motor interference in people with and without ET during a standard and progressively more complex dual-task measure of gait, mobility, and balance. We report two main findings: (1) dual-task performance during a standard and complex TUG assessment did not differ between individuals with and without ET, and (2) people with ET prioritized cognitive performance over motor performance; however, this was not different from the non-ET group. These results are contrary to our hypothesis as there were no significant differences between the groups regarding motor and cognitive dual-task effects and both groups prioritized cognitive performance when performing the walking and talking assessments. Nevertheless, our study findings provide novel and impactful findings concerning the interplay between mobility and cognition in ET. Dual-task performance requires managing and executing multiple tasks simultaneously, which can significantly impact both motor and cognitive functions28,29. When individuals are required to perform a cognitive task while engaging in a motor task, they may experience a trade-off in performance, often needing to prioritize one task over the other15. Dual-tasking may be impaired in ET, owing to motor and cognitive deficits29. This suggests that people with ET might need to adopt specific strategies to prioritize either motor stability or cognitive task performance, potentially leading to impaired overall function. Our study’s examination of dual-task performance and task prioritization in Essential Tremor is crucial for understanding how individuals with ET manage competing demands and for developing strategies to improve their overall functional capacity.

Our findings provide a comprehensive and holistic study of dual-task performance and attention allocation in people with ET. The study outcomes are comprehensive and holistic, addressing both cognitive and motor dual-task effects29, which is crucial given the prevalence of motor and cognitive deficits in individuals with ET28,29. Performing concurrent motor and cognitive tasks interfered with motor and cognitive performance equally in the ET and Non-ET groups, consistent with previous studies on ET26,27. For example, Bove and colleagues examined dual-task performance during static posturography in individuals with ET and reported that dual-task performance does not significantly differ between individuals with ET and controls, indicating that balance control is only minimally affected in ET26. Similarly, during a dual-task walking paradigm, prior work in ET demonstrated that verbal fluency performance was similar between ET and Non-ET groups, consistent with the outcomes of our study27. These limited studies that have examined dual-task performance in ET have incorporated static balance or straight-line walking assessments. However, in contrast to previous work, our study examined dual-task performance during both a standard and a more challenging task (water-carry TUG), which may better reflect real-life transitional motions. Several factors, such as an individual’s physical capacity or awareness of environmental hazards, can influence motor and cognitive performance when performing a motor and cognitive task simultaneously and may explain the variability observed in our study30. Nonetheless, our results emphasize the importance of cognitive-motor task performance in daily life and suggest that people with ET are not differentially affected compared to those without ET. Task complexity, introduced by adding a water-carrying task during the TUG, did not differentially affect overall or phase-specific TUG performance in people with Essential Tremor. Despite the common clinical characteristics of upper extremity tremor and cognitive impairment in Essential Tremor, both ET and Non-ET groups performed similarly during the water-carry TUG assessment. Prior studies in frail older adults incorporating a similar water-carrying paradigm noted that reduced performance in the more complex task was sensitive in distinguishing those at fall risk31. Lundin and colleagues incorporated a water-carrying task into the TUG for frail older adults. Their research revealed that a 4.5-second difference between the standard TUG and the water-carrying TUG effectively identified individuals who were frailer and at greater risk of falls, highlighting the potential utility of including more complex motor tasks31. Additionally, research indicates that tremor amplitude in ET is modulated by sensory feedback, with increased feedback linked to greater tremor severity32. This suggests that while sensory feedback can significantly impact tremor amplitude and potentially influence dual-task performance. However, our study did not reveal such differences. Therefore, the ET group may already have been walking cautiously, as suggested by our main effect of group, or perhaps the water-carry activity was not a challenging enough stimulus. Engaging in two attention-demanding tasks simultaneously creates competition for attentional resources and challenges the brain to determine the order of priority between the tasks19,23. Our study is among the first to examine task prioritization during dual-task paradigms in ET and demonstrate that people with ET pay more attention to cognitive task performance compared to motor task performance. Task prioritization may be driven by minimizing danger and maximizing pleasure33. In a “posture first” approach, individuals prioritize gait tasks over secondary cognitive tasks, likely minimizing the risk of instability and falls. This has been demonstrated in healthy young and older adults20,21. However, our findings of cognitive prioritization in people with ET align more with a “posture second” strategy, similar to what has been observed in a Parkinson’s disease population30,34,35. The posture second strategy is characterized by diverting more attentional resources to the cognitive task over the motor task performance30. For example, prior research has highlighted that during dual-talk paradigms in which the walking tasks became more challenging and complex, dual-task performance became compromised, with younger and older adults tending to prioritize maintaining their gait and balance, even if it meant performing worse on the cognitive task, adopting this “posture first” strategy. However, even in the more challenging water-carry TUG assessment, individuals with ET perform similarly to individuals with Parkinson’s disease, adopting more of a “posture second approach.” Our sample of ET participants may have enhanced postural reserves, allowing them to focus more on the secondary cognitive task. Moreover, it is also plausible that people with ET may prioritize cognitive task performance owing to difficulties estimating hazards and lacking self-awareness of limitations36. These novel findings enhance our comprehension of the interplay between cognition and motor performance in people with ET. The observed task prioritization pattern in individuals with ET may have important clinical implications. For example, prior literature has depicted an association between the adoption of this “posture second’ approach and fall risk. Lundin-Olsson and colleagues demonstrated that the frequency of stops during walking while talking (i.e., adopting a “posture second” approach) could predict future falls37. Prior research has also linked this “posture second” strategy to an increased risk of falls in older adults38. Furthermore, the preference for allocating attention to cognitive performance over motor performance during dual-task conditions suggests that people with ET may adapt their behavior to minimize the impact of symptoms on daily activities requiring cognitive engagement. This insight could inform rehabilitation approaches for individuals with ET. Clinicians might consider incorporating dual-task training that emphasizes cognitive-motor integration, potentially aiding individuals with more effective strategies when both cognitive and motor demands are high. Additionally, this finding underscores the importance of assessing cognitive and motor aspects when evaluating functional capacity in ET in real-world settings. While our results do not indicate a unique prioritization strategy in ET, they highlight the need for a holistic approach to ET management that considers both cognitive and motor domains in treatment planning and outcome assessment. There are limitations in our study that should be considered when interpreting the results. The limited small sample size of 30 individuals (15 with ET and 15 without ET) may have affected our outcomes. While this limitation may have influenced our ability to identify interaction effects between group and condition, we believe this limited dataset addresses critical gaps in the existing ET literature and provides a necessary first step at enhancing our understanding of the influence of cognition on mobility in people with ET. Moreover, when investigating motor and cognitive alterations during the dual-task assessments, our primary motor outcomes focused on the overall duration of the standard and water-carry TUG. Examining other motor outcomes could provide more nuanced information about the effects of ET on dual-task performance and prioritization. Furthermore, it is important to acknowledge that medications used by patients with ET might alter their motor or cognitive performance. However, we consistently ensured that all participants were tested in their therapeutic optimal state. these limitations, our study outcomes contribute significantly to understanding walking and functional mobility deficits in ET and represent an important first step in providing a holistic examination of dual-task performance in detail in ET. Dual-task performance was not differentially impacted in people with ET compared to people without ET during both a standard and more challenging water-carry TUG assessment. Further, people with ET allocate more attentional resources to cognitive task performance when performing a walking and talking assessment, adopting a ‘posture second’ strategy. This work increases our understanding of the relationship between cognition and physical function in people with ET. While the outcomes of this study should be interpreted with caution due to the limited sample size, the findings nonetheless provide impactful insights and valuable information to guide future research in this area. The results offer important preliminary evidence, but larger-scale studies are needed to confirm and expand upon these initial observations.

Methods

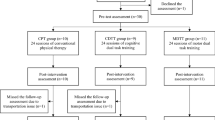

Participants provided written informed consent prior to study participation, as approved by the Auburn University Institutional Review Board ( Approval Number: 21-598EP2201). The study was conducted according to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Data collection occurred between March 2022 and April 2023. Participants visited the lab for a one-time visit. Participants first completed questionnaires including demographic and clinical history information and balance confidence and fear of falling questionnaires. Next, participants completed cognitive assessments followed by single and dual-task standard and water-carry TUG assessments which are described in more detail in the “Experimental protocol” section.

Participants

30 age-matched people aged with and without ET (15 per group) were recruited to participate in this study. To participate in this study, participants were required to be aged between 18-and 87, have a neurologist-confirmed diagnosis of ET, and report being free from lower-extremity injuries or surgeries in the past 12 months that may have changed their walking pattern or limited their capacity to complete the protocol. Participants were excluded from the study if they could not follow study commands or instructions or if they had a dual diagnosis of another neurological condition. People with ET reported to the study in their optimal therapeutic state. To ensure consistency, participants were instructed to maintain their usual medication regimen for managing tremors and maintain any treatments that were efficacious in controlling tremors. Participants who fulfilled the screening process were then enrolled by the research assistant to participate. Participant characteristics can be observed in Table 2.

Experimental protocol

Participants then visited the laboratory for a one-time cross-sectional assessment consisting of questionnaires, cognitive assessments, and dual-task assessments. All assessments were performed by trained graduate students under the supervision of the lab director, a movement disorders expert, ensuring the necessary skills for accurate administration. After acquiring demographics and other baseline measures, balance confidence was assessed using the Activities Specific Balance Scale (ABC)39, and fear of falling was measured using the Fall Efficacy Scale (FES)40. Retrospective fall history was obtained from participants regarding whether or not they had fallen within the previous three months. Considering that individuals with ET are susceptible to cognitive deficits29 participants then completed a series of baseline cognition assessments, including the Mini-Mental State Exam to test global cognition41, the Digit Span Forward and Backward assessed attention and working memory42, and the Trails Making Test A and B examined processing speed, attention and executive function43. Each assessment was chosen as prior studies have indicated deficits in global cognition, memory, attention, executive function, and processing speed in individuals with ET44. All assessments were performed in the same order and by the same administrator. The Essential Tremor Rating Assessment Scale (TETRAS)45, motor performance and activities of daily living scales were used to quantify tremor severity. The lab director, an experienced movement disorders researcher, administered the TETRAS scale. A fall log was also administered to document any falls or near falls during four weeks post-laboratory visit. Next, participants were equipped with six wireless inertial measurement units (Opal, Generation 2, APDM, Inc, Portland, OR.), with three-dimensional sensors at the sternum and lumbar spine and one on each foot and wrist. Data were captured (128 Hz) and processed using Moveo Explorer data collection software (APDM Inc Portland, OR, USA). The Moveo Explorer™ software analyzed the raw data from all sensors using an integrated and automatic algorithm to calculate the duration of TUG phases. Participants then completed a series of instrumented TUG assessments46,47,48. Participants first completed a seated cognitive task followed by four TUG assessments: (1) Standard TUG, (2) Water-Carry TUG, (3) Standard Dual Task TUG, and (4) Water-Carry Dual Task TUG. Participants were not provided explicit instructions on how to complete the tasks (i.e., no instructions to prioritize one strategy over another), and all assessments were performed using the same armless chair (height 37 cm). The cup was filled with 325 ml of water for the water-carry TUG tasks. The research assistant was the consistent administrator for each assessment and was supported by other research team members to ensure each participant’s safety.

Standard TUG and standard dual-task TUG

Participants sat with their backs against an armless chair. When the administrator verbally prompted the participant to begin, the participant stood up with their arms across their chest, walked to a piece of tape on the floor three meters away, turned around, and then walked back three meters and returned to a seated position. During the standard dual-task TUG, the participants were instructed to complete the same task while completing a concurrent cognitive task. For this task, participants were asked “to name as many animals as possible” while performing the TUG assessment. Participants began naming items while seated and then started the TUG assessment when prompted by the researcher.

Water-carry TUG and water-carry dual-task TUG

Participants again began seated with their backs against the chair, but here, they were instructed to also carry a tray with a cup full of water. When prompted, participants once again stood, walked to a piece of tape on the floor three meters away, turned around, and then walked back three meters and returned to a seated position, all while carrying a tray with a cup full of water. During the water-carry dual-task TUG, participants were instructed to complete the same task while completing a simultaneous cognitive task. For this task, participants were asked “to name as many colors” as possible while carrying a tray with a cup of water while performing the TUG assessment. The participants began naming items while seated and then started the water-carry TUG assessment when prompted. For the water-carry TUG assessment, a table was also placed beside the participant to place the tray and the water cup if needed during the sit-to-stand or stand-to-sit phases of the water-carry TUG assessment. Participants began seated holding the tray and then returned to a seated position holding the tray at the end of the assessment.

Seated cognitive task

Participants also completed a seated single-task verbal fluency task in which they sat quietly and were asked to “name as many fruits and vegetables” as possible. The number of correct responses was provided in the same amount of time it took the participant to complete the standard dual-task TUG, and the Water-Carry dual-task was used for analysis. This task was incorporated to examine this aspect of executive function in isolation and to facilitate the calculation of the cognitive dual-task effect and prioritization49. A verbal fluency cognitive task was incorporated throughout the dual-task paradigm as it has previously been used to examine executive functions49. A recent prospective study of gait and balance in people with Essential Tremor showed that impaired executive function scores were the most consistent predictors of gait and balance impairments14.

Data analysis

Task-specific interference was assessed by calculating the motor dual task effect (motDTE) and the cognitive dual task effect (cogDTE) using the following Eqs. 17,18,22,50. These measures depict how motor (i.e., walking) and cognitive (i.e., verbal fluency) task performance change when performed simultaneously compared to when performed in isolation on their own.

This motor dual task effect (motDTE) equation measured motor-related interference during standard and water-carry TUG tasks. The overall time to complete each standard and water-carry TUG assessment was incorporated into the calculation and represented motor (i.e., walking) performance. To be consistent with the recognized operational definition of dual-task effects, a negative sign was added to the formula as a greater value (i.e., longer time to complete the TUG) indicates worse performance17,18,50. Therefore, a positive motDTE value reflects facilitation; motor performance (TUG duration) improved (i.e., quicker) with the addition of a concurrent cognitive task. Conversely. a negative motDTE value reflects interference; motor performance (TUG duration) was worse (i.e., longer) with the addition of a concurrent cognitive task.

The cognitive dual task effect (cogDTE) equation measured cognitive-related interference during the standard and water-carry TUG tasks. The number of correct responses to the verbal fluency assessment were incorporated into the calculation and represented cognitive performance. A positive cogDTE value indicates facilitation; cognitive performance (the number of correct responses to the verbal fluency task) increased (i.e., more correct responses) with the addition of a concurrent motor task. A negative cogDTE value indicates interference; cognitive performance (the number of correct responses to the verbal fluency task) decreased (fewer correct responses) with the addition of a concurrent motor task.

Task prioritization was then calculated using the following Eqs. 17,22:

A positive task prioritization value reflects motor priority, indicating that performance on the motor task was prioritized. A negative task prioritization value reflects cognitive priority, indicating that performance on the verbal fluency task was prioritized. Outcomes used to assess cognitive-motor interference are further defined in Supplemental Table 1.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics Version 26 [IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA]. To describe the population in our study, means and standard deviations were calculated for the total population and each group (ET and Non-ET). The distribution of postural transition and cognitive-motor interference outcomes were assessed using the Shapiro–Wilks test, the inspection of Q–Q plots, and the examination of skewness and kurtosis values. Group comparisons for continuous variables such as age, height, body mass, balance confidence, fear of falling, and cognitive outcomes (TMT-A and B, Digit Span Test, and MMSE) were made using independent sample t-tests. As fall history and sex are categorical variables, chi-square tests of independence were conducted to compare groups. No group comparisons were made for TETRAS, QUEST, or prospective falls, as these were administered to only the ET group. Cognitive motor interference was contrasted in people with and without ET utilizing both task-specific interference measures (motDTE and cogDTE) and task prioritization. To compare task-specific interference, we conducted mixed-repeated measures ANOVA by Group (ET and Non-ET) x Condition (Single Task and Dual-Task) for both the standard and water-carry TUG. Separate models were run, one with single- and dual-task TUG performance (total TUG duration) and the other with single- and dual-task cognitive performance (correct numbers listed). Further, univariate ANOVAs were also run to compare the motDTE and cogDTE between groups during standard and water-carry TUGs. To compare task prioritization during both standard and water-carry TUGs, univariate ANOVA was conducted to assess the effect of Group (ET and Non-ET) on prioritization. If significant main effects or interactions were detected in the ANOVA models, post hoc comparisons were corrected using the Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. If the assumption of sphericity was violated according to Mauchly’s test, Greenhouse-Geisser adjusted degrees of freedom were interpreted. Significance was set at ɑ < 0.05 for all analyses. The sample size analysis presented here was conducted post-hoc, based on our total sample of 30 participants (15 in the ET group and 15 in the Non-ET group). Given this design and assuming an alpha level of 0.05 and a power of 0.8, our current sample size is capable of detecting a medium effect size, corresponding to ŋ² = 0.21. According to this analysis, a total of 30 subjects was sufficient to detect this effect size.

Data availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Louis, E. D. & McCreary, M. How common is essential tremor? Update on the worldwide prevalence of essential tremor. Tremor. Other Hyperkinet. Mov. 11, 28 (2021).

Bhatia, K. P. et al. Consensus statement on the classification of tremors. From the task force on tremor of the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society. Mov. Disord. 33, 75–87 (2018).

Singer, C., Sanchez-Ramos, J. & Weiner, W. J. Gait abnormality in essential tremor. Mov. Disord. 9, 193–196 (1994).

Hubble, J. P., Busenbark, K. L., Pahwa, R., Lyons, K. & Koller, W. C. Clinical expression of essential tremor: Effects of gender and age. Mov. Disord. 12, 969–972 (1997).

Louis, E. D. Functional correlates of lower cognitive test scores in essential tremor. Mov. Disord. 25, 481–485 (2010).

Louis, E. D. & Rao, A. K. Functional aspects of gait in essential tremor: A comparison with age-matched Parkinson’s disease cases, dystonia cases, and controls. Tremor. Other Hyperkinet. Mov. 5, (2015).

Lim, E.-S., Seo, M.-W., Woo, S.-R., Jeong, S.-Y. & Jeong, S.-K. Relationship between essential tremor and cerebellar dysfunction according to age. J. Clin. Neurol. 1, 76 (2005).

Rao, A. K., Gillman, A. & Louis, E. D. Quantitative gait analysis in essential tremor reveals impairments that are maintained into advanced age. Gait Post. 34, 65–70 (2011).

Roper, J. A. et al. Spatiotemporal gait parameters and tremor distribution in essential tremor. Gait Post. 71, 32–37 (2019).

Earhart, G. M., Clark, B. R., Tabbal, S. D. & Perlmutter, J. S. Gait and balance in essential tremor: Variable effects of bilateral thalamic stimulation. Mov. Disord. 24, 386–391 (2009).

Louis, E. D., Benito-León, J., Vega-Quiroga, S. & Bermejo-Pareja, F. Faster rate of cognitive decline in essential tremor cases than controls: A prospective study. Eur. J. Neurol. 17, 1291–1297 (2010).

Bermejo-Pareja, F., Louis, E. D. & Benito-León, J. Risk of incident dementia in essential tremor: A population-based study. Mov. Disord. 22, 1573–1580 (2007).

Louis, E. D. Non-motor symptoms in essential tremor: A review of the current data and state of the field. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 22(Suppl 1), S115–S118 (2016).

Dowd, H. et al. Prospective longitudinal study of gait and balance in a cohort of elderly essential tremor patients. Front. Neurol. 11, 1–14 (2020).

Yogev-Seligmann, G., Hausdorff, J. M. & Giladi, N. The role of executive function and attention in gait. Mov. Disord. 23, 329–342 (2008).

Al-Yahya, E. et al. Cognitive motor interference while walking: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 35, 715–728 (2011).

Longhurst, J. K. et al. A novel way of measuring dual-task interference: The reliability and construct validity of the dual-task effect battery in neurodegenerative disease. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair. 36, 346–359 (2022).

Plummer, P. et al. Cognitive-motor interference during functional mobility after stroke: State of the science and implications for future research. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 94, 2565-2574.e6 (2013).

Plummer, P. & Eskes, G. Measuring treatment effects on dual-task performance: A framework for research and clinical practice. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9, 1–7 (2015).

Woollacott, M. & Shumway-Cook, A. Attention and the control of posture and gait: A review of an emerging area of research. Gait Post. 16, 1–14 (2002).

Bloem, B. R., Valkenburg, V. V, Slabbekoorn, M. & van Dijk, J. G. The multiple tasks test. Strategies in Parkinson’s disease. Exp Brain Res 137, 478–486 (2001).

Peterson, D. Effects of gender on dual-tasking and prioritization in older adults. SSRN Electron. J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4054432 (2022).

Yogev-Seligmann, G. et al. How does explicit prioritization alter walking during dual-task performance? Effects of age and sex on gait speed and variability. Phys. Ther. 90, 177–186 (2010).

Pedullà, L. et al. The patients’ perspective on the perceived difficulties of dual-tasking: Development and validation of the Dual-task Impact on Daily-living Activities Questionnaire (DIDA-Q). Mult Scler. Relat. Disord. 46, (2020).

Abasıyanık, Z. et al. Patient-reported outcome measures for assessing dual-task performance in daily life: A review of current instruments, use, and measurement properties. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, vol. 19 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215029 (2022).

Bove, M., Marinelli, L., Avanzino, L., Marchese, R. & Abbruzzese, G. Posturographic analysis of balance control in patients with essential tremor. Mov. Disord. 21, 192–198 (2006).

Rao, A. K., Uddin, J., Gillman, A. & Louis, E. D. Cognitive motor interference during dual-task gait in essential tremor. Gait Post. 38, 403–409 (2013).

Arkadir, D. & Louis, E. D. The balance and gait disorder of essential tremor: What does this mean for patients?. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 6, 229–236 (2013).

Janicki, S. C., Cosentino, S. & Louis, E. D. The cognitive side of essential tremor: What are the therapeutic implications?. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 6, 353–368 (2013).

Bloem, B. R., Grimbergen, Y. A. M., van Dijk, J. G. & Munneke, M. The, “posture second” strategy: A review of wrong priorities in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 248, 196–204 (2006).

Lundin-Olsson, L., Nyberg, L. & Gustafson, Y. Attention, frailty, and falls: The effect of a manual task on basic mobility. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 46, 758–761 (1998).

Welzel, J. et al. The interplay of sensory feedback, arousal, and action tremor amplitude in essential tremor. Sci. Rep. 14 (2024).

Williams, L. M. An integrative neuroscience model of ‘significance’ processing. J. Integr. Neurosci. 5, 1–47 (2006).

Yogev, G. et al. Dual tasking, gait rhythmicity, and Parkinson’s disease: Which aspects of gait are attention demanding?. Eur. J. Neurosci. 22, 1248–1256 (2005).

Chapman, G. J. & Hollands, M. A. Evidence that older adult fallers prioritise the planning of future stepping actions over the accurate execution of ongoing steps during complex locomotor tasks. Gait Posture 26, 59–67 (2007).

Yogev-Seligmann, G., Hausdorff, J. M. & Giladi, N. Do we always prioritize balance when walking? Towards an integrated model of task prioritization. Mov. Disord. 27, 765–770 (2012).

Lundin-Olsson, L., Nyberg, L. & Gustafson, Y. ‘Stops walking when talking’ as a predictor of falls in elderly people. Lancet. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(97)24009-2 (1997).

Beauchet, O. et al. Stops walking when talking: A predictor of falls in older adults? Eur. J. Neurol.. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02612.x (2009).

Powell, L. E. & Myers, A. M. The activities-specific balance confidence (ABC) scale. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 50A, M28-34 (1995).

Tinetti, M. E., Richman, D. & Powell, L. Falls efficacy as a measure of fear of falling. J. Gerontol. 45, P239–P243 (1990).

Folstein, M. F., Robins, L. N. & Helzer, J. E. The mini-mental state examination. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 40, 812 (1983).

Blackburn, H. L. & Benton, A. L. Revised administration and scoring of the Digit Span Test. Journal of Consulting Psychology vol. 21 139–143 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1037/h0047235 (1957).

Partington, J. E. & Leiter, R. G. Partington’s Pathways Test. Psychol. Service Center J. 1, 11–20 (1949).

Louis, E. D., Benito-León, J., Ottman, R. & Bermejo-Pareja, F. A population-based study of mortality in essential tremor. Neurology 69, 1982–1989 (2007).

Elble, R. et al. Reliability of a new scale for essential tremor. Mov. Disord. 27, 1567–1569 (2012).

Mancini, M. et al. ISway: A sensitive, valid and reliable measure of postural control. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 9, 59 (2012).

Salarian, A. et al. iTUG, a sensitive and reliable measure of mobility. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 18, 303–310 (2010).

Mancini, M. et al. Mobility lab to assess balance and gait with synchronized body-worn sensors. J. Bioeng. Biomed. Sci. Suppl.1, 7 (2011).

Lezak, M. D., Howieson, D. B. & Loring, D. W. Neuropsychological Assessment (Oxford University Press, 2004).

Kelly, V. E., Janke, A. A. & Shumway-Cook, A. Effects of instructed focus and task difficulty on concurrent walking and cognitive task performance in healthy young adults. Exp. Brain Res. 207, 65–73 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank those who participated in this study and all those who helped distribute and spread awareness of our study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PGM and JAR conceived and designed research; PGM analyzed data; PGM prepared figures; PGM. drafted manuscript; PGM, JAR, WMM, KN, and HCW edited and revised manuscript; JAR, WMM, HCW, and KN approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Monaghan, P.G., Murrah, W.M., Walker, H.C. et al. Cognitive-motor interference in people with essential tremor. Sci Rep 14, 23456 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74310-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74310-x