Abstract

Objective: To investigate the association between coal dust exposure and the occurrence of dyslipidemia in coal mine workers, and identify relevant risk factors. Methods: We selected a population who underwent occupational health examinations at Huainan Yangguang Xinkang Hospital from March 2020 to July 2022. Participants were divided into two groups based on the presence or absence of dyslipidemia, and their baseline information was collected, including records of coal dust exposure. We employed single-factor analysis to identify risk factors for dyslipidemia and adjusted for confounding factors in the adjusted models. Additionally, we explored the effects in different populations using stratified analysis, smooth curve fitting, and propensity score matching. Finally, we confirmed the causal relationship between coal dust exposure and dyslipidemia by examining tissue sections and lipid-related indicators in a mouse model of coal dust exposure. Results A total of 5,657 workers were included in the study, among whom 924 individuals had dyslipidemia and 4,743 individuals did not have dyslipidemia. The results of the single-factor analysis revealed that dust exposure, age, BMI, blood pressure, and smoking were statistically significant risk factors for dyslipidemia (p < 0.05). Additionally, the three multivariate models, adjusted for different confounders, consistently showed a significant increase in the risk of dyslipidemia associated with coal dust exposure (Model 1: OR, 1.869; Model 2: OR, 1.863; Model 3: OR, 2.033). After conducting stratified analysis, this positive correlation remained significant. Furthermore, propensity score matching analysis revealed that with increasing years of work, the risk of dyslipidemia gradually increased, reaching 50% at 11 years. In the mouse model of coal dust exposure, significant coal dust deposition was observed in the lungs and livers of the mice, accompanied by elevated levels of total cholesterol (TC), alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). Conclusion Exposure to coal dust significantly increases the risk of developing dyslipidemia, and this positive correlation exists in different populations, particularly with increasing years of work, resulting in a higher risk. Keywords: Dust, occupational health, dyslipidemia, risk factors, cross-sectional study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coal mining plays a pivotal role in the global economy, yet it is not without significant occupational health risks, particularly due to exposure to coal dust. The process of coal extraction and processing involves multiple steps, each a potential source of inhalation of fine particulate matter. Such exposure has been associated with a range of health issues, including respiratory diseases and metabolic disorders like dyslipidemia1. Dyslipidemia, characterized by abnormal lipid levels in the blood—encompassing hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and mixed hyperlipidemia—is a prevalent metabolic disorder and a significant risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, which are among the leading causes of mortality worldwide2,3.

The literature increasingly implicates occupational exposure to coal dust in the development of dyslipidemia. For instance, studies by Dehghani et al.4 and Eslamidoost et al.5 have highlighted the impact of air pollution and specific pollutants like NO2 on chronic diseases and metabolic disorders, resonating with the occupational challenges faced by coal miners. These workers are often subjected to harsh conditions such as poor ventilation, strong winds, darkness, humidity, and extreme temperatures, which exacerbate the risk of occupational diseases6.

Epidemiological evidence indicates a rising prevalence of dyslipidemia, especially in regions with high levels of environmental pollutant exposure, like coal mines7. The awareness and treatment rates for dyslipidemia among adults in Jilin Province, China, lag significantly behind those in Beijing, pointing to a pressing need for improved understanding and management of dyslipidemia in areas with substantial occupational exposure to coal dust and other pollutants8. This study aims to address these gaps by conducting a cross-sectional analysis to assess the risk of dyslipidemia due to dust exposure and by identifying potential risk factors. Furthermore, animal experiments will verify the causal relationship between dust exposure and dyslipidemia, contributing to a deeper understanding of the occupational causes of dyslipidemia and informing prevention and management strategies for high-risk occupational groups.

While studies have shown that coal dust exposure can elevate blood lipid levels, as demonstrated by higher levels of triglycerides and very-low-density lipoprotein in workers9, the influence of confounding factors like physical exercise and diet has not been fully explored10. In this study, a cross-sectional analysis will be conducted to assess the degree of risk of dyslipidemia caused by coal dust exposure and identify potential risk factors. Additionally, animal experiments will be carried out to verify the causal relationship between dust exposure and dyslipidemia (Fig. 1).

Inhalation of coal dust leads to disorder of liver deposition and metabolism, which may lead to hyperlipidemia.

Methods

Study population

The study included non-exposed individuals and coal dust-exposed individuals who underwent health examinations at Xin Kang Hospital from March 2020 to July 2022. The selection criteria for the study population were as follows:

Inclusion Criteria: (1) Non-exposed individuals: Administrative staff of the company with no history of coal dust exposure. (2) Coal dust-exposed individuals: Frontline mining workers of the company with documented exposure to coal dust.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Incomplete health examination data. (2) Presence of lipid-affecting diseases, including hypothyroidism, diabetes, and kidney disease.

Baseline information such as age, occupation, BMI, hypertension, smoking history, alcohol consumption, exercise habits, and dietary habits was meticulously collected to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the participants’ health status.

Occupational health examinations and definition of standards

Occupational health examinations were conducted to assess the health status of the study participants. These examinations included a thorough medical history, physical examination, and laboratory tests to evaluate various health parameters. The duration of coal dust exposure was recorded for each participant, with special attention paid to the potential health impacts of long-term exposure.

BMI standard: Normal range was defined as 18.5–23.9 kg/m², while values below 18.5 kg/m² or above 23.9 kg/m² were considered abnormal.

Blood pressure standard: High blood pressure was defined as systolic BP ≥ 140mmHg and/or diastolic BP ≥ 90mmHg.

Smoke: Defined as smoking at least one cigarette per day for more than one month.

Drink: Defined as drinking alcohol at least once a week for more than one year.

Physical exercise: Defined as engaging in physical activity more than three times a week, with each session lasting more than two hours.

Dietary habits: Defined as whether or not vegetables were consumed daily during a meal.

Lipid standards: Dyslipidemia was diagnosed based on triglycerides > 1.7mmol/L and/or cholesterol > 5.2 mmol/L.

Assessment of coal dust exposure

Coal dust exposure was assessed through a combination of self-reported data and environmental monitoring. Participants were asked to provide detailed information on their work history, including the duration and intensity of coal dust exposure. Environmental samples were collected to measure the concentration of particulate matter in the air, ensuring an accurate assessment of exposure levels.

Identification and control of confounding factors

Potential confounding factors were identified through a thorough review of the literature and consultation with occupational health experts. These factors included age, BMI, blood pressure, smoking, alcohol consumption, exercise habits, and dietary habits. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to control for these factors, ensuring a robust analysis of the relationship between coal dust exposure and dyslipidemia.

Model 1 was adjusted for no covariates. Model 2 was adjusted for age and BMI. Model 3 was adjusted for all potential confounding factors. Subgroup analysis was further conducted to explore the relationship between dust exposure and dyslipidemia in different populations. Weighted generalized additive models and smooth curve fitting methods were used to explore non-linear relationships. Threshold effect analysis was performed to identify the optimal inflection point.

Mouse model construction

Twenty wild-type SPF C57BL/6 male mice, aged 8–10 weeks (22–27 g), were housed under constant conditions of temperature (24 ± 1℃), relative humidity (60 ± 5%), and a 12-hour light-dark cycle (light from 08:00–20:00). They had ad libitum access to water and were fed standard mouse chow for one week to acclimatize. Large chunks of raw coal obtained from the Panji coal mining area in Huainan were crushed and ground to um-level coal dust, followed by high-pressure sterilization. Sterile coal dust suspension was prepared in sterile physiological saline at a concentration of 50 mg/mL. The animals were randomly divided into the early-stage group (14 days of coal dust inhalation), late-stage group (28 days of coal dust inhalation), and control group (n = 10). The mice were anesthetized using isoflurane (RWD Life Science, Shenzhen, China). Coal dust suspension (20µL/mouse, 3 times every day) was administered nasally11. On the 14th and 28th days of the experiment, the mice were euthanized using cervical dislocation, and tissue and blood samples were collected.

Collection and HE staining of mouse tissues

Immediately following euthanasia, the lung and liver tissues were rapidly removed from the mice in each group. Some lung and liver tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for histological analysis using HE staining. Tissue staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using the Hematoxylin-Eosin staining kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, C0105S, China).

Processing of mouse serum and measurement of dyslipidemia

After 2 and 4 weeks of intervention, the mice were anesthetized using isoflurane, their eyes were enucleated, and approximately 700µL of blood was collected and centrifuged at 3000r/min for 5 min to obtain serum samples. The levels of relevant lipid metabolism indicators, including total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), were measured using an automated biochemical analyzer. The assay kits were purchased from Mindray Biomedical Electronics Co., Ltd., with the following batch numbers: total cholesterol (Lot No: 141622013), triglycerides (Lot No: 141721003), alanine aminotransferase (Lot No: 140121005), aspartate aminotransferase (Lot No: 140222012), high-density lipoprotein (Lot No: 142122002), and low-density lipoprotein (Lot No: 142022003).

Ethical considerations

The collection of health examination information and animal experiments involved in this study were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Anhui University of Science and Technology (No. 2021032). All research procedures were conducted following the Helsinki Medical Ethics Standards and the ARRIVE guidelines. The use of medical test data obtained the informed consent of all participants. During the whole research process, the privacy and confidentiality of participants were maintained. Animal procedures are conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the European Parliament Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals for scientific purposes. Mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation under isoflurane anesthesia. All mice are kept in laboratory animal room, and their living conditions and welfare are supervised by the ethics Committee of their unit.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using EmpowerStats software. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, while categorical variables were presented as percentages. A significance level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Unpaired t-tests were used to compare continuous variables, while Pearson’s chi-square test was employed to assess differences in categorical variables. Furthermore, the prevalence of abnormal lipid profiles was calculated based on various characteristics present. Univariate and multivariate regression analyses were conducted to evaluate the correlation between lipid levels and risk factors. Associations between lipid abnormalities and risk factors were assessed using odds ratios (ORs).

Result

Baseline characteristics of the participants

According to the inclusion criteria, a total of 5,657 participants were included for analysis. The frontline coal dust exposure group consisted of 3,063 individuals, among whom 640 individuals had dyslipidemia, accounting for 20.89%. The non-exposure group consisted of 2,294 individuals, among whom 284 individuals had dyslipidemia, accounting for 12.38%. The baseline characteristics of the participants are described in Table 1.

Coal dust exposure is one of the risk factors for dyslipidemia

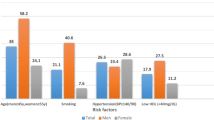

Univariate analysis (Table 2) incorporating the baseline characteristics of coal mine workers showed that dust exposure, sex, age, BMI, and abnormal blood pressure were significant risk factors for dyslipidemia among coal miners (p < 0.05).

Multivariate regression analysis

In this study, we utilized multivariate regression analysis to investigate the relationship between coal dust exposure and the risk of dyslipidemia among coal miners. The analysis was conducted in three models to account for different levels of confounding factors (Table 3).

Model 1 (Unadjusted):

This model was designed to provide a baseline estimate of the association between dust exposure and dyslipidemia without adjusting for any potential confounding factors. The odds ratio (OR) of 1.8639 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.606–2.176) indicates a significant increase in the risk of dyslipidemia among coal miners exposed to dust. The p-value of less than 0.001 confirms the robustness of this association.

Model 2 (Adjusted for Age and BMI):

Building on Model 1, Model 2 included adjustments for age and body mass index (BMI), two key demographic factors known to influence metabolic health. The OR of 1.863 (95% CI: 1.600-2.171) suggests that, even after accounting for these factors, the risk of dyslipidemia remains significantly elevated among those exposed to coal dust. The slight decrease in the OR compared to Model 1 indicates that age and BMI may partially explain the observed association, but the effect of dust exposure remains substantial.

Model 3 (Fully Adjusted):

Model 3 was the most comprehensive, adjusting for a range of potential confounding factors including age, BMI, blood pressure, smoking, alcohol consumption, exercise habits, and dietary habits. The OR of 2.033 (95% CI: 1.734–2.384) indicates that, after controlling for all these factors, the risk of dyslipidemia among coal miners exposed to dust is even higher, increasing by 103.3%. This finding suggests that the initial estimate of risk may have been conservative, and the true impact of dust exposure on dyslipidemia risk could be more pronounced than previously thought.

To ascertain whether the positive association between coal dust exposure and dyslipidemia applies to all populations, stratified analysis was conducted. BMI, blood pressure, smoking, drinking, exercise, and diet were dichotomized, and it was observed that in different subgroups, the probability of developing dyslipidemia remained higher among those exposed to coal dust compared to the unexposed group (Fig. 2).

Effect of work duration on the occurrence of dyslipidemia in coal dust-exposed population

To further explore the specific impact of exposure duration on dyslipidemia, a secondary analysis was conducted on a sample of 3,063 frontline coal mine workers. Propensity score matching (PSM) method was employed, with a caliper value set to 0.01 and a 1:1 ratio of matched pairs as the standard. Adjustments were made for age, BMI, blood pressure, smoking, drinking, exercise, and diet. This resulted in a final matched sample of 1,244 individuals, with 622 in both the control and abnormal groups (Table 4). This matching process aimed to achieve a more balanced distribution of confounding factors between the treatment and control groups.

Analyzing the matched sample reduces bias introduced by confounding factors and provides a more reliable assessment of the treatment effect. Using smoothed curve fitting, the influence of work duration on the occurrence of dyslipidemia was explored. The results showed that as work duration increased, the risk of dyslipidemia gradually rose among coal mine workers exposed to dust. When conducting threshold effect analysis on work duration (Table 5). it was found that the risk increased with longer work duration (OR: 1.272, 95% CI: 1.241–1.304, p < 0.001). Moreover, the threshold effect analysis revealed that the likelihood of developing dyslipidemia reached 50% when work duration exceeded 11 years (Fig. 3).

The influence probability of working years on the occurrence of dyslipidemia caused by coal dust exposure. A each black dot represents a sample. The ordinate 0.0 represents no dyslipidemia, 1.0 represents dyslipidemia, and the red dot represents the corresponding working years of each sample. B the solid red line represents the smooth curve fitting between variables, and the blue bar represents the 95% confidence interval of fitting.

Pathological observation of exposed coal dust mouse model and blood lipid measurement

For the mouse model exposed to coal dust, lung and liver tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). It was observed that with the prolonged exposure time, significant deposition of coal dust particles was found in the lungs and livers of the exposed group mice (Fig. 4A-B).

Observation of mouse tissue section and determination of blood lipid index. HE staining and polarizing results of mouse lung (a) and liver (b) tissue sections show that the white arrows are deposited coal particles.TC (C), ALT (D), AST (E), HDL-C (F) and LDL-C (G) were measured in control group, early coal dust exposure group (14 days) and late coal dust exposure group (28 days).

Biochemical analysis revealed that the exposed group had significantly higher levels of total cholesterol (TC), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) compared to the control group (p < 0.01). However, the high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) concentration in the high-fat group was significantly lower than that in the control group (p > 0.01). Among these, TC, ALT, and HDL-C showed a gradual increase or decrease trend with prolonged exposure time. ALT and LDL-C exhibited an increase followed by a decrease or remained stable as the exposure time extended (Fig. 4C-G).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study involving coal mine workers, we primarily investigated the relationship between exposure to coal dust and the occurrence of dyslipidemia. The results of our study demonstrated an increased risk of dyslipidemia among workers exposed to coal dust compared to those who were not exposed. Furthermore, among the coal dust-exposed workers, the risk of developing dyslipidemia reached 50% after 10 years of work duration, indicating the need for timely attention to this population. Additionally, we observed the deposition of coal dust particles in the liver tissue of animals, suggesting that it may be one of the factors contributing to the development of dyslipidemia.

Literature reports have established a strong association between air pollution, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and CVD-related mortality12. Dyslipidemia, considered an important factor for CVD, are closely linked to particulate matter (PM) present in dust. In a cross-sectional analysis involving 6,587 patients, a 2% increase in serum total lipid levels was observed with each unit increment of 1 µg/m3 of PM2.5 exposure13. Another investigation utilizing the NHANES database conducted by Ryan P Shanley et al. revealed that individuals chronically exposed to PM10 in dust exhibited a 2.42% increase in triglyceride levels (95% CI: 1.09–3.76)14. However, a cohort study involving rural residents in Henan, China, showed adverse changes in lipid levels associated with higher PM1 exposure, characterized by increased total cholesterol (TC) (95% CI: 0.11-0.31%) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) (95% CI: 0.61-0.90%), and decreased triglycerides (TG) (95% CI: 2.43-2.93%) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) (95% CI: 0.35-0.59%)15. Similarly, a longitudinal study conducted in Shijiazhuang, China, demonstrated positive associations between exposure to PM2.5 and PM10 and elevated levels of triglycerides, total cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol16. In our study, significant increases in triglyceride or cholesterol levels were observed among coal mine workers exposed to dust. Considering the differences in these results, it is possible that factors such as Sex, BMI, or blood pressure may have influenced the outcomes. Therefore, we adjusted for these variables in the multivariate regression models and conducted further stratified analysis.

Age is considered one of the destructive risk factors for developing dyslipidemia. Several studies17,18,19 have shown a positive correlation between participants’ concentrations of TC, LDL-C, and TG with age, while HDL-C concentration exhibited a significant negative correlation. This indirectly reflects that older individuals may have difficulty recognizing normal blood lipid levels and lack awareness of timely screening and preventive measures, indicating a lack of understanding and awareness regarding the prevention of dyslipidemia. This is also the reason why we adjusted for age in our regression model. dyslipidemia, as a metabolic disorder, are characterized by high levels of fats in the blood, leading to the accumulation and blockage of the heart and blood vessels. Obesity is closely related to dyslipidemia, and studies have confirmed that dyslipidemia are primarily driven by insulin resistance and pro-inflammatory adipokines20. Obesity is currently assessed primarily by measuring body mass index (BMI), a combination of weight and height. A prospective cohort study conducted in China21 found a positive correlation between BMI and the development of dyslipidemia, regardless of general or abdominal obesity. Obesity and persistent obesity were significant risk factors for dyslipidemia in Chinese adults. In a Chinese study22, the likelihood of hypertension and dyslipidemia occurring together was 13.81%, and the cumulative risk of hypertension and dyslipidemia combined was considered higher than the combined risk of hypertension and dyslipidemia alone in cardiovascular disease (CVD) and coronary heart disease (CHD)23. Therefore, the impact of blood pressure abnormalities cannot be disregarded when assessing the risk of dyslipidemia among workers.

Additionally the length of employment among coal mine workers is another important influencing factor that should not be overlooked. The results of our study revealed that the risk of developing dyslipidemia gradually increased with the length of employment among coal mine workers exposed to dust pollution, reaching 50% after 11 years of work duration. Furthermore, this risk continued to rise with prolonged exposure duration. These findings provide valuable reference for the formulation of health management measures in related industries in the future.

Evidence from animal models, showing the deposition of coal dust particles in vital organs such as the liver, suggests a potential mechanism that connects coal dust exposure with dyslipidemia. Once inhaled, particulate matter and hazardous chemicals found in coal dust initiate an inflammatory response in the respiratory tract and lungs. This inflammation triggers the release of cytokines, including interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), which, upon entering the bloodstream, can disrupt lipid metabolism1,24. Specifically, the metabolism and clearance of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) are impaired, leading to elevated LDL levels and an increased risk of LDL oxidation and arterial deposition, thereby heightening the risk of cardiovascular diseases25,26. Moreover, oxidative stress induced by coal dust can exacerbate these metabolic disruptions, promoting the progression of atherosclerosis27. These findings underscore the importance of effective dust exposure control and early intervention for dyslipidemia among coal miners.

While our study provides valuable insights into the relationship between coal dust exposure and dyslipidemia, it is not without limitations. One of the primary limitations is the cross-sectional nature of the study, which limits our ability to establish causality. Although animal experiments were conducted to explore potential causal relationships, further prospective studies are necessary to validate these findings. Additionally, our study did not account for all potential confounding factors. Lifestyle habits, sleep patterns, and other behavioral factors that could influence dyslipidemia were not included in our data collection, which may introduce bias into our conclusions. Future research should aim to include these factors to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between coal dust exposure and dyslipidemia.

Despite these limitations, our study provides valuable insights into the potential health risks associated with coal dust exposure. The findings underscore the need for targeted interventions to reduce occupational exposure, such as improved ventilation systems, personal protective equipment, and regular health screenings28,29. Health education and awareness programs for workers are also crucial, focusing on the prevention and management of dyslipidemia.

Conclusion

Exposure to coal dust is one of the risk factors for dyslipidemia. Furthermore, at 11 years of exposure, the risk of developing dyslipidemia reaches 50%, indicating the need for timely attention.

Data availability

The study data may be applied to the correspondent author via email and used with the consent of the author’s unit.

References

Liu, T. & Liu, S. The impacts of coal dust on miners’ health: A review[J]. Environ. Res., 190109849. (2020).

Leon-Mejia, G. et al. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity induced by coal and coal fly ash particles samples in V79 cells[J]. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int. 23 (23), 24019–24031 (2016).

Leon-Mejia, G. et al. Intratracheal instillation of coal and coal fly ash particles in mice induces DNA damage and translocation of metals to extrapulmonary tissues[J]. Sci. Total Environ., 625589–625599. (2018).

Dehghani, S. et al. Ecological study on household air pollution exposure and prevalent chronic disease in the elderly[J]. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 11763 (2023).

Eslami, D. Z. et al. Dispersion of SO(2) emissions in a gas refinery by AERMOD modeling and human health risk: a case study in the Middle East[J]. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 34 (2), 1227–1240 (2024).

Yang, L. et al. Mining Employees Safety and the Application of Information Technology in Coal Mining: Review[J]. Front. Public. Health, 9709987. (2021).

He, H. et al. Dyslipidemia awareness, treatment, control and influence factors among adults in the Jilin province in China: a cross-sectional study[J]. Lipids Health Dis., 13122. (2014).

Pirillo, A. et al. Global epidemiology of dyslipidaemias[J]. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 18 (10), 689–700 (2021).

Tuluce, Y. et al. Increased occupational coal dust toxicity in blood of central heating system workers[J]. Toxicol. Ind. Health. 27 (1), 57–64 (2011).

Fan, Y. et al. Prevalence of dyslipidaemia and risk factors in Chinese coal miners: a cross-sectional survey study[J]. Lipids Health Dis. 16 (1), 161 (2017).

Li, B. et al. Vitamin D3 reverses immune tolerance and enhances the cytotoxicity of effector T cells in coal pneumoconiosis[J]. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf., 271115972. (2024).

Aryal, A., Harmon, A-C. & Dugas, T-R. Particulate matter air pollutants and cardiovascular disease: strategies for intervention[J]. Pharmacol. Ther., 223107890. (2021).

McGuinn, L-A. et al. Association of long-term PM(2.5) exposure with traditional and novel lipid measures related to cardiovascular disease risk[J]. Environ. Int., 122193–122200. (2019).

Shanley, R-P. et al. Particulate Air Pollution and Clinical Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors[J]. Epidemiology. 27 (2), 291–298 (2016).

Mao, S. et al. Is long-term PM(1) exposure associated with blood lipids and dyslipidemias in a Chinese rural population?[J]. Environ. Int., 138105637. (2020).

Zhang, K. et al. The association between ambient air pollution and blood lipids: a longitudinal study in Shijiazhuang, China[J]. Sci. Total Environ., 752141648. (2021).

Liu, X. et al. Dyslipidemia prevalence, awareness, treatment, control, and risk factors in Chinese rural population: the Henan rural cohort study[J]. Lipids Health Dis. 17 (1), 119 (2018).

Li, Q. et al. The Association between Chronological Age and Dyslipidemia: A Cross-Sectional Study in Chinese Aged Population[J] 18667–18675 (Clin Interv Aging, 2023).

Izumida, T. et al. Association among age, gender, menopausal status and small dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: a cross-sectional study[J]. BMJ Open. 11 (2), e41613 (2021).

Vekic, J. et al. Obesity and dyslipidemia[J]. Metabolism, 9271–9281. (2019).

Cao, L. et al. Effects of Body Mass Index, Waist circumference, Waist-to-height ratio and their changes on risks of Dyslipidemia among Chinese adults: the Guizhou Population Health Cohort Study[J]. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health, 19(1). (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Comorbidity Analysis according to sex and age in hypertension patients in China[J]. Int. J. Med. Sci. 13 (2), 99–107 (2016).

Rehman, S. et al. Cardiovascular Disease Mortality and potential risk factor in China: A Multi-dimensional Assessment by a Grey Relational Approach[J]. Int. J. Public. Health. 671604599. (2022).

Wang, W. et al. Glycogen metabolism reprogramming promotes inflammation in coal dust-exposed lung[J]. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 242113913. (2022).

Kaur, S. et al. Effect of occupation on lipid peroxidation and antioxidant status in coal-fired thermal plant workers[J]. Int. J. Appl. Basic. Med. Res. 3 (2), 93–97 (2013).

Peng, F. et al. Serum metabolic profiling of coal worker’s pneumoconiosis using untargeted lipidomics[J]. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int. 29 (56), 85444–85453 (2022).

Tirado-Ballestas, I-P. et al. Oxidative stress and alterations in the expression of genes related to inflammation, DNA damage, and metal exposure in lung cells exposed to a hydroethanolic coal dust extract[J]. Mol. Biol. Rep. 49 (6), 4861–4871 (2022).

Zhou, G. et al. Study on MICP dust suppression technology in open pit coal mine: Preparation and mechanism of microbial dust suppression material[J]. J. Environ. Manage. 343118181. (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Identification of high-risk population of pneumoconiosis using deep learning segmentation of lung 3D images and radiomics texture analysis[J]. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 244108006. (2024).

Funding

Supported by Research Funds of Joint Research Center for Occupational Medicine and Health of IHM (No. OMH-2023-04); Open Research Fund of Anhui Province Engineering Laboratory of Occupational Health and Safety (No. AYZJSGCLK202202004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DX, DY and HD: conception and design, and study supervision. ZH, TH, FJ and HW : development of methodology, analysis and interpretation of data, and writing of the manuscript. HC and LY: review of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, H., Tao, H., Fu, J. et al. Cross-sectional analysis of dyslipidemia risk in coal mine workers: from epidemiology to animal models. Sci Rep 14, 26894 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74718-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74718-5