Abstract

Floods accompanied by thunderstorms in developed cities are hazardous, causing damage to infrastructure. To secure infrastructure, it is important to employ an integrated approach, combining remote sensing, GIS and precipitation data. The model was developed based on the estimation of event-based runoff and investigated the relationship between runoff and impervious surfaces. The novel approach of combining Hydrologic Engineering Center’s River Analysis System (HEC-GeoRAS) along with satellite imagery was utilized, where spatial data was combined with real-time values to run the model. As a first step, the Hydrologic Engineering Center-Hydrologic Modeling System (HEC-HMS) model was fed with information about precipitation, slope, soil type, as well as land use and land cover. The results reveal that the subbasins of Deira, Nief and Jumeirah have the largest impervious area and, thus, a higher probability of flood occurrence. The model was calibrated and validated using previous runoff events and by comparing observed and simulated streak flow and peak discharge against those reported in previous studies. It was found that the model is efficient and can be used in similar regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Floods, as a response to climate change and abnormal heavy rains, are a temporary overflow of valley plains and drainage networks. They occur on one-third of the Earth’s surface, where more than 70% of the world’s population resides1. In arid regions, they occur in narrow coastal areas, narrow mountainous valleys (wadi courses), and coastal cities in lowlands due to terrain’s characteristics. They can cause serious damage to infrastructure and loss of human life1,2. The northern part of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), including the Emirate of Dubai, experienced intense rains and flash floods between 9 March and 12 March 2016, with more than 155 mm (7.55 inches) of accumulated rainfall.

The wide availability of remote sensing data and machine learning algorithms has allowed researchers to map LULC and predict flash floods on a regional scale efficiently and economically1,2,3. Recently, the application of flood forecasting has become increasingly important due to its ability to provide real-time warning information about areas with a higher probability of flash flood occurrence. These outcomes can be achieved by estimating the volume of runoff, calculating the amount of stored water and determining the likelihood of flash floods2. Thus, building computer-based hydraulic models and analyzing drainage basins are among the researchers’ and decision makers’ preferred methods as they allow for qualitative assessment of the risks1,4. Hydraulic modeling is an important systematic tool for predicting streamflow. These types of numerical models are important for flood simulation, qualitative assessment of floods and providing accurate information about flood profiles3.

In the absence of gauging stations and meteorological data, utilization of satellite data can be an efficient approach for improving the livability of an arid region by modeling and predicting rainfall and runoff events3. The Hydrologic Engineering Center’s River analysis system (HEC-GeoRAS) and Hydrologic Modeling System (HEC-HMS), which are widely used in the literature, were employed to simulate and model surface runoff based on hourly precipitation4. Accurate prediction of streamflow allows a better understanding of the hydraulic setting and helps prevent damage to infrastructures5.

Recently, several flash flood models have been developed based on an estimation of river discharge and streamflow6, the integration of Geographic Information System (GIS), remote sensing, and rainfall-runoff modeling in HEC-HMS7, geohydrological parameters and magnitude indexing1, and geospatial technology to map flash floods inundation, site selection for flash floods shelters, and assessment of flash floods8, as well as hydrological parameters such as hourly rainfall and speed of surface runoff9,10,11. The integration of HEC-HMS and HEC-GeoRAS has been applied to model and analyze flood risk and river discharge in an arid region3. This study modifies an integrated approach, combining remote sensing and precipitation data, to model and analyze flood events in rapidly urbanizing area. The study area selected was the highly urbanized city of Dubai in the UAE. This study also aimed to assess the influence of the intensive urbanization on floods. The model begins by extracting hydrological parameters such as subbasins, soil texture, topographic slope and runoff.

This study is the first attempt to model flood events in the city of Dubai using a combined approach of traditional modeling (HEC-HMS) along with satellite imagery for mapping flood-prone areas through HEC-GeoRAS. Using this approach, peak discharge and precipitation loss were calculated and compared with the real-time values. The largest subbasins were identified in the emirate of Dubai, which are prone to extensive flooding due to a lack of proper stormwater networks and an overly impervious area. The proposed model represents a significant advancement in modifying predicted maps of flash floods, land subsidence and landslides produced using hydraulic models. The results provide a better understanding of the spatial relationship between surface runoff, past flood events, and peak discharge. The main findings serve as a valuable reference for decision-makers and hydrologists for future planning and related projects.

Study area

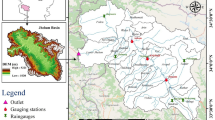

Dubai is the second largest city in the UAE and the most rapidly developed city in the world. It extends between longitudes 54º 59’ to 55º 36’ 42” E and latitudes 24º 42’ 30” to 55º 16’ 59” N (Fig. 1), and is located about 150 km east of Abu Dhabi, the UAE capital and 7 km west of the Emirate of Sharjah. The Emirate of Dubai spreads over an area of about 3,885 km2, while the city is approximately 700 km2 at an elevation of 5 m above seal level (a.s.l). It is divided into two by the Dubai Creek (Khor Dubai): the first part is known locally as Deira (northeast), while the second is known as Bur Dubai (southwest).

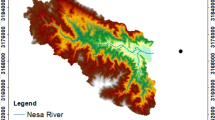

The climatic condition of the Emirate of Dubai is warm and sunny with average temperatures ranging from 25ºC in the winter to 37ºC in the summer, and with humidity averaging 90% in the summer. Rainfall in Dubai is infrequent and mostly rains during winter, with mean monthly ranges from 0.6 to 18.8 mm (https://services.dubaiairports.ae/dubaimet/met/climate.aspx). The annual rainfall varies from 30 mm in the southeastern desert near the city of Dubai to 180 mm in the mountainous areas in the north and east (Fig. 2).

The maximum number of rainfall days over the study is four to six days per month during the period from December to March, while the maximum daily precipitation value is 1.2 mm during March (Fig. 2a, b)12. The estimated annual rainfall over the mountainous and coastal areas accounts for about 97% of the total rainfall over the northern part of the United Arab Emirates. Hydrologically, the area is drained by several surface and near-surface paleochannels (wadi courses1). Their trends are generally in the NW-SE, NNW-SSE, NE-SW and NNE-SSW directions. These features play an important role in flash floods by accumulating rainwater from upstream and causing damage to houses and farms downstream.

The Emirate of Dubai has a variety of LU LC classes comprising built-up, waterbody, garden/park, farmland and bare land. Among these LULC classes, the two most dominant are built-up and vegetation areas. The rapid growth of Dubai has resulted in a sharp decline in desert areas and water quality, and, thus, agricultural deterioration13. Vegetation areas (gardens and parks) can be found in and around the city and along main roads. Agricultural activity is limited to sand dune corridors, desert and gravel plains in sand dune areas, and near Hatta, wherever paleochannels (wadis) are found. Dubai is divided into three major geomorphic regions: (i) the eastern mountainous area, (ii) a dune field in the middle, and (ii) the coastal area in the west13 (Fig. 1).

Datasets and methods

Datasets

Three different datasets were used in this study. The first dataset consisted of Landsat images with a spatial resolution of 30 m, acquired on 4 March 2016 and 2023. This dataset was used to classify and monitor changes in LULC and to observe the cloud cover and intensive precipitation in the study area. The second dataset was the digital elevation model (DEM) and images of the Phased Array type L-band Synthetic Aperture Radar (PALSAR) of the Advanced Land Observing Satellite (ALOS) with a spatial resolution of 30 m. The ALOS DEM and images were downloaded from the web page of the United States Geological Survey (USGS) (http://gdex.cr.usgs.gov/gdex/) and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, Earth Observation Research Center (https://www.eorc.jaxa.jp/ALOS/en/palsar_fnf/data/index.htm). We used this type of sensor owing to its ability to penetrate extremely dry sand sheets and image near-surface features over a regional scale in a cost-effective manner14,15. Additionally, the ALOS DEM has the lowest Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) than SRTM DEM, the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) DEM16,17. The third dataset was the precipitation data collected from meteorological stations and the webpage of the National Centre of Metrology webpage (https://www.ncm.ae/Radar_UAE_Merge). Since 1990, 61 flood events have been reported across the study area, and the most severe event occurred between January and March with 144 mm (5.66 inches)17.

Flood modeling

To modify the physically-based hydrologic model for the city of Dubai, it is important to employ suitable parameters and appropriate methods. The proposed model starts by preparing input parameters followed by calibration and validation (Fig. 3). These parameters include a LULC map, a digital elevation model (DEM), and precipitation data.

Model parameters

Topographic slope

Terrain parameters such as topographic slope, topographic relief and topographic curvatures play important roles in determining the infiltration rate of rainwater, flow accumulation, and transit and dissipation zones18. Infiltration is inversely proportional to high terrain parameter values; i.e., water infiltration increases with adecrease in topographic slope, topographic convergence, and altitude13,19,20. Thus, terrain parameter maps were included in the proposed approach. Terrain parameters were calculated from DEM using 3D Analyst tools that utilize the topographical model tool in ArcGIS v10.8 software. The calculated maps were classified into five categories from very low to very high (Fig. 4a).

Soil texture

The soil texture, soil types and physical characteristics of soil, such as porosity and permeability affect the rate of infiltration, flood rise, soil moisture, runoff coefficient and flood volume. All soil types were digitized from the soil map of Dubai (Fig. 4b).

Precipitation data

Rainfall data are a critical input parameter in all hydrological models. To model and analyze flash floods in developed cities, it is important to study and understand the spatial and temporal distribution of a given basin. In this study, two sources of meteorological data were collected. The first source was the rain gauges distributed in Dubai, Sharjah, and Ajman Airports. Since these three emirates are located side-by side and the rainfall is almost similar in these locations, the data from these gauges were used along with the second source, the Integrated Multi-satellite Retrievals for GPM (IMERG) level-3. GPM data for precipitation were obtained from the NASA website (https://pmm.nasa.gov/data-access/downloads/GPM) (Fig. 4c).

For this study, level 3 IMERG product data were used, with a spatiotemporal resolution of 10 × 10 km and a temporal resolution at half-hourly intervals for rainfall data across five studied subbasins. This data was collected for the flood event of March 2016, which was previously validated by Mohamed et al1,5. for the UAE. These data were normalized to half-hourly intervals and used in the model.

LUC classification and change detection

To map and monitor LULC changes, a set of training data (as pixels) was collected from the QuickBird imagery with a spatial resolution of 0.6 m and validated using a field check at the location where the authors live. The collected training datasets consisted of four classes (built-up, park/garden, farmland and industrial areas)1. After training data collection, we ran the Spectral Analysis Mapper (SAM) classifier, which is a suitable solution for LULC classification in Dubai13. The classifier, developed by Kruse et al21, and offers a physical-based spectral classification, which uses an n-D angle to match the pixels to reference spectra.

The classification process was performed using a supervised classification tool implemented in ENVI v4.5 software. To reduce errors in the produced LULC maps, several post-processing steps were performed by applying a 3 × 3 Sobel filter for better boundary discrimination of LULC classes, applying majority/minority analysis with a 3 × 3 kernel and central pixel of 1, and applying sieve classes using a group minimum threshold of 2, as well as the number of neighbours and a 3 × 3 operator-size for clump parameters. The resultant LULC consists of two main classes namely; built-up (residential and industrial areas) and vegetation (gardens and farms) (Fig. 4d).

Delineation of subbasins

Concerning the subbasins, a hydrology tool implemented in ArcMap v10.8 was used to automatically extract a flow direction grid. Subsequently, the subbasins were delineated using a flow accumulation function, followed by stream order and basin delineation (Fig. 5).

Creating of the curve number (CN) map

To calculate the Curve Number (CN) grid for each subbasin, two steps were performed. In the first step, a CN Lookup table was prepared. The table comprises a combination of different soil and land use groups, defining the value of each land use/ hydrology group combination. Subsequently, the SCS curve numbers were calculated based on SCS tables that are widely reported in the literature. The calculated table summarizes values ranging from 0 to 100. A value of 0 indicates no runoff potential, while a value of 100 indicates high potential runoff corresponding to all precipitation22. In other terms, a value of 0 indicates permeable soil with a higher rate of infiltration, while a value of 100 is assigned directly to the surface water. The calculation of the Weighted Curve Number (WCN)22 for each subbasin was performed using the following equation:

Where, \(\:{A}_{i}\) is the area for the ith land-use class, \(\:{CN}_{i}\) represents Curve Number for the ith land use class and \(\:WCN\) denotes the Weighted Curve Number.

The CN map was created using HEC-GeoMS implemented in the ArcGIS v9.2 software. The resultant map consists of different subbasins with different CN and area and impervious cover. Finally, WCN was calculated to calibrate the proposed model. The output of HEC-HMS was plotted using a code developed in Python (Appendix A).

Model setup

Setting up the proposed model consists of three elements: (i) rainfall and discharge, (ii) subbasin,which includes selecting the Soil Conservation Service (SCS) curve number, which is a loss method, selecting the transform method using the SCS Unit Hydrograph method, and selecting baseflow method using Recession method, and (iii) reach, which involves selecting a routing method and modeling meteorologic data using Thiessen polygon method. The SCS-CN is based on the fact that the accumulated rainfall excess depends on the soil texture, LULC, cumulative precipitation, and the previous moisture condition, as estimated using the following equation:

Where, Pe is the accumulated precipitation excess at time t (mm); P is the accumulated rainfall depth at time t (mm); Ia is the initial abstraction (mm) = 0.2 S; and S is the potential maximum retention (mm).

The maximum retention, S, and watershed characteristics are related through an intermediate dimensionless parameter, the curve number (CN) as given in the equation below:

Where, CN is the SCS curve number used to represent the combined effects of the primary characteristics of the catchment area.

Calculation of lag time

To calculate the Lag time for each subbasin, the lag for the peak runoff and loss method was implemented in the Soil Conservation Service (SCS) approach. The SCS components include the unit hydrograph (UH) lag time, which is related to the time of concentration, Tc, for the ungauged watershed, and the lag for the peak runoff and loss method. Subsequently, the total area (in km2), the length of streams, and the topographic slope were calculated in a GIS environment for each subbasin.

Manning’s coefficient was adopted from the HEC-HMS manual22. For example, for a smooth surface, Manning’s coefficient value was 0.011. The P2 value of a 2-year, 24-hour rainfall depth was acquired from Abu Dhabi Municipality stormwater and subsoil drainage master plan23. Other parameters such as \(\:{t}_{shallow}\) and \(\:{t}_{sheet}\) were calculated using the following equation:

whereas \(\:{t}_{shallow}\) is the sum of travel time in shallow flow segments. The resulting lag time is shown in Table 1. where, \(\:\varvec{L}\) is length of channel; \(\:\varvec{V}\) is velocity; \(\:\varvec{S}\) is mean Slope (%); \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{2}\) is 2-year 24-hour rainfall in mm/h; value of \(\:\varvec{n}\) adopted from HEC-HMS manual22.

After adding the basin model, the meteorological model was specified for precipitation as a specified hyetograph, by connecting each subbasin to the downstream sink. Additionally, control specifications were applied to start from 00:00 h on 8-Mar-2016 until 23:00 h on 10-Mar-2016. The time interval specified was 30 min. Precipitation gauges were linked to each subbasin, and the rainfall time series data of 30 minutes (in mm/h) were entered into the model. Finally, the model was set to run for the given date and time.

Model calibration and validation

The proposed model was calibrated using rainfall and flood events from March 8, 2016, to March 10, 2016. After that, it was validated based on the coefficient of determination (R2) value. Finally, the model was validated and simulated.

Results

The model was set to run for simulation on all five subbasins using the half-hourly data (Appendix B). The half-hourly precipitation data (March 2016) for each subbasin were used to extract water balance. Figure 4 shows five subbasins, which were extracted from a DEM using the proposed model, draining the study area and presented in different color codes to facilitate interpretation. The areas are characterized by different terrain parameters such as slope (Fig. 4a), elevation and topographic curvatures. They are covered by different soil textures (Fig. 4b) and, thus, each subbasin has its hydrologic characteristics. The results also reveal that spatial distribution, short duration and precipitation intensity are the most significant features of floods and rainfall events. Rainfall events occur during the period from November to March, with irregular rainfall events during the summer season. Spatially, the southern and eastern parts of the study area have a higher rate of precipitation than the western part (subbasin 4 and 5).

As shown in Figs. 6 and 7, the Deira subbasin (subbasin 1) has experienced the lowest rate of precipitation with a value of 20.43 mm, and has the highest percentage of the impervious surface area with a value of 65%. The low value for loss is due to the highest percentage of impervious surface area. On the contrary, Jabal Ali-1 subbasin (subbasin 4) experienced the highest rate of precipitation (33.11 mm) and loss rate with a value of 29.1 mm. This is because the area is covered by a lower percentage of impervious areas, estimated to be 12% of the total area of the study area. This difference is attributed to the impact of soil infiltration, impervious area, drainage network density, and rate of evapotranspiration24. Comparing the loss time series with impervious surface area, we found a negative relationship between intensive urbanization and flood occurrence.

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the hydrologic parameters of five subbasins calculated during the period from 8 March 2016, at 00:00 h to March 10, 2016, at 23:00 h using the HEC-HMS model. They include the total area for each subbasin, Lag Time, and predicted rate of peak discharge. As it appears from the tables, Jumeirah subbasin (subbasin 3), which is drained by streams covering an area of about 330 km2, has the highest value (2802.1 m3) for total direct runoff and peak discharge (88.6 m3/s), while Jabal Ali-1 subbasin (subbasin 4), which is drained by streams covering an area of about 30 km2, has the lowest value (66.3 m3) for the total direct runoff and the smallest value (9.9 m3/s) for peak discharge. These differences reflect differences in CN, impervious area, topographic slope, and drainage network area of each subbasin.

The spatial trend (rising and falling) of the hydrograph shows that the responses to precipitation events reflect surface runoff. Figures 6 and 7show that the Jummera subbasin (subbasin 3), which occupies an area of about 330 km2 and is covered by an impervious area of about 181.5 km2 (55%), has a higher value (537.5) for lag time and CN and WCN (65%) and is characterized by a topographic slope of about 2.7%. On the contrary, the subbasin of Jabal Ali-1 (subbasin 4), which occupies an area of about 30 km2 and is covered by impervious area of about 12%, has the lowest value (22.6) for lag time and (46%) and CN (46) (Tables 1 and 2). The percentage of impervious surface area for each subbasin was estimated based on LULC class types (Figs. 4d and 5).

Spatial analysis showed that the total area of the LULC for each subbasin strongly controls the impervious surface and infiltration rate, and CN value. The latter parameter is one of the most important parameters in the HEC-HMS model. Intensive urbanization in the eastern part of the city of Dubai has increased the impervious surface, surface runoff, and the composite CN for the subbasins of Deira, Nief and Jumeirah, making them susceptible to runoff and flooding. The severity of flooding and its timing are governed by the hydrologic effects of the ground surface3,7,8. In the same context, the high peak of flood events presents a possible threat to human life and infrastructure.

Estimation of different hydraulic parameters is one of the benefits of the model in ungauged regions; thus, model validation is important for such studies. To achieve this purpose, streamflow is simulated and compared against observed values after running the model repeatedly. Figure 8 shows a graph of the relationship between the observed and simulated hydrographs for the period from 08 March to 10 March 2016. The accuracy of the hydrologic model was determined based on the coefficient of determination (R2) value. 22The graph also exhibits an acceptable fit and correlation between the simulated and observed values with an R22 of 92.8% for the calibrated period. Thus, according to Moriasi et al25, the simulated model can be arbitrated as acceptable and satisfactory.

Discussion

A hydrologic model using the HEC-HMS method was applied for the modeling and simulation of runoff hydrographs in the city of Dubai, UAE. The initial calibrated parameters, which include topographic slope, stream networks, and soil texture, were derived based on geomorphological characteristics. Five subbasins characterize the coastal area of Dubai, with differences in their hydrographic parameters.

A higher runoff coefficient was observed in Deira, Nief and Jumeirah subbasins. The reason for this is the large area of impervious surface with lower soil permeability. Thus, they have a higher probability of flooding and damage to infrastructures compared to Jabal Ali 1 and 2, which are built in sand dune areas. This finding agrees well with Nu-Fang et al.26, who concluded that the runoff coefficient is high for areas with less infiltration compared to those covered by sand dunes and forest areas. It is apparent that the subbasins of Diera, Nief and Jumeirah are more prone to flooding than Jabal Ali 1 and 2, and the impact of flooding on the built-up area (residential and industrial) is much greater than on agricultural area. In other words, Diera, Nief and Jumeirah are zones with a higher probability of flood occurrence and damage to infrastructures. The reason for this is that they are covered by large impervious surface areas (buildings, roads, and vegetation cover). Additionally, they are characterized by a higher rate of peak discharge and total direct runoff8. The rapid increase in runoff volume is significantly affected by the porosity and permeability of the soil in each subbasin, while the length of the rainstorm has an important influence on flood occurrence. In the same context, CN, lag time, and initial abstraction are strongly controlled by topographic slope, soil texture, and LULC (Table 1).

According to Elmahdy et al.1, there are two types of flash floods that differ in their magnitudes, impacts, and controlling factors. The first type is the mountainous flash floods that hit villages and cities on and at the foot of the Oman Mountains, such as Ras Al Khaimah and Fujairah, while the second type is coastal floods that hit the main cities such as Dubai and Sharjah. The magnitude of mountainous flash floods is much greater than that of coastal floods. This is due to an abrupt change in slope in the main wadi and the short distance between the mountainous area (source of rainfall) and main cities1. Thus, mountainous flash floods cause damage to infrastructure and loss of human life, while coastal floods cause delays in flight schedule, traffic jams, and school closures.

The result indicated a strong relationship between simulated and observed runoff across the study area, with promising results for the simulation of rainfall runoff. Estimating different hydrological parameters in ungauged subbasins is one of the main benefits of the proposed model. The proposed model is cost-effective and time efficient, and performs significantly better than the Lumped model and traditional field observation methods3. Compared to the Lumped model, the modified model performs better in calculating total runoff volume and runoff discharge. However, some limitations and uncertainties are associated with the obtained parameters.

Conclusion

The city of Dubai is one of the most important economic cities in the world and is occasionally exposed to heavy rain events within its coastal areas (subbasins). To address this problem, a hydrologic model, which integrates HEC-HMS and SCS-WCN methods, was applied to simulate the floods of March 8, 2016, in the city of Dubai. The model was fed with different factors such as slope, soil, precipitation, and LULC. The initial model calibration parameter was derived using geohydrologic and geomorphological characteristics. The results showed that the area is drained by five subbasins with differences in their areas and hydrographic parameters, and floods are strongly influenced by impervious area (LULC), runoff, stream length, topographic slope, subbasin area, and soil texture. The largest subbasins covered by impervious surfaces have the highest direct runoff. These include Deira, Nief and Jumeirah, which are zones of higher flood probability. The Jumeirah subbasin, which occupies an area of 330 km2 and covers about 181.5 km2 (55%), has a higher value (537.5) for lag time and CN and WCN (65%). On the contrary, the subbasin of Jabal Ali-1 (subbasin 4), which occupies an area of about 30 km2 and is covered by impervious area of about 3.5km2 (12%), has the lowest value (22.6) for lag time and a direct runoff of 66.3 m3.

The simulation process offered valuable information about the probability of flood occurrence in an arid region in a time and cost-effective manner. Urban areas with large impervious surfaces occasionally experience damaging floods resulting from rainfall anomalies in response climate change. The model is a simple and powerful tool with efficient performance for flood forecasting in an arid region and provides a better understanding of the spatial relationship between urbanization and flood occurrence. Future work should focus on designing a new real-time warning system and modifying the model by applying a DEM with a spatial resolution of 1 m and more accurate meteorological data. Additional applications of the HEC-HMS model should be encouraged to confirm its suitability for the Dubai subbasins.s

Data availability

Data underlying this research is available in Appendix B and C.

References

Elmahdy, S., Ali, T. & Mohamed, M. Flash Flood susceptibility modeling and magnitude index using machine learning and geohydrological models: a modified hybrid approach. Remote Sens. 12, 2695 (2020).

Hamdan, A. N. A., Almuktar, S. & Scholz, M. Rainfall-runoff modeling using the HEC-HMS model for the Al-Adhaim River catchment, northern Iraq. Hydrology. 8, 58 (2021).

AL-Hussein, A. A., Khan, S., Ncibi, K., Hamdi, N. & Hamed, Y. Flood analysis using HEC-RAS and HEC-HMS: a case study of Khazir River (Middle East—Northern Iraq). Water. 14, 3779 (2022).

Elshorbagy, A., Corzo, G., Srinivasulu, S. & Solomatine, D. P. Experimental investigation of the predictive capabilities of data driven modeling techniques in hydrology-part 1: concepts and methodology. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 1931–1941 (2010).

Bessar, M. A., Matte, P. & Anctil, F. Uncertainty analysis of a 1d river hydraulic model with adaptive calibration. Water. 12, 561 (2020).

Lerat, J. et al. Do internal flow measurements improve the calibration of rainfall-runoff models? Water Resour. Res. 48, (2012).

El Alfy, M. Assessing the impact of arid area urbanization on flash floods using GIS, remote sensing, and HEC-HMS rainfall–runoff modeling. Hydrol. Res. 47, 1142–1160 (2016).

Ilia, I., Tsangaratos, P., Tzampoglou, P., Chen, W. & Hong, H. Flash flood susceptibility mapping using stacking ensemble machine learning models. Geocarto Int. 37, 15010–15036 (2022).

Tsakiris, G. Flood risk assessment: concepts, modelling, applications. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 1361–1369 (2014).

Ahmad, H. F., Alam, A., Bhat, M. S. & Ahmad, S. One dimensional steady flow analysis using HECRAS–A case of River Jhelum, Jammu and Kashmir. Eur. Sci. J. 12, 340–350 (2016).

Hamed, Y. et al. Modelling of potential groundwater artificial recharge in the transboundary algero-tunisian Basin (Tebessa‐Gafsa): the application of stable isotopes and hydroinformatics tools *. Irrig. Sci. 71, 137–156 (2022).

Giri, S. & Singh, A. K. Human health risk assessment via drinking water pathway due to metal contamination in the groundwater of Subarnarekha River Basin, India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 187, 63 (2015).

Elmahdy, S. I. & Mohamed, M. M. Remote sensing and geophysical survey applications for delineating near-surface palaeochannels and shallow aquifer in the United Arab Emirates. Geocarto Int. 30, 723–736 (2015).

Groucutt, H. S. et al. The Middle Palaeolithic of the Nejd, Saudi Arabia. J. Field Archaeol. 41, 131–147 (2016).

Roth, L. & Elachi, C. Coherent electromagnetic losses by scattering from volume inhomogeneities. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 23, 674–675 (1975).

Santillan, J. R., Makinano-Santillan, M. & Makinano, R. M. Vertical accuracy assessment of ALOS World 3D-30 M Digital Elevation Model over northeastern Mindanao, Philippines. in IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS) 5374–5377 (IEEE, 2016). (2016).

Elmahdy, S., Ali, T. & Mohamed, M. Hydrological modeling of Ar rub Al Khali, Arabian Peninsula: a modified remote sensing approach based on the weight of hydrological evidence. Geocarto Int. 37, 6251–6271 (2022).

Florinsky, I. V. Relationships between topographically expressed zones of flow accumulation and sites of fault intersection: analysis by means of digital terrain modelling. Environ. Model. Softw. 15, 87–100 (2000).

Kiss, R. Determination of drainage network in digital elevation models, utilities and limitations. J. Hung. Geomathematics. 2, 17–29 (2004).

Rao, L. N. Environmental impact of uncontrolled disposal of e-wastes. Int. J. ChemTech Res. 6, 1343–1353 (2014).

Kruse, F. A. et al. The spectral image processing system (SIPS)—interactive visualization and analysis of imaging spectrometer data. Remote Sens. Environ. 44, 145–163 (1993).

Feldman, A. D. Hydrologic Modeling System HEC-HMS, Technical Reference Manual. (2000).

ADM. Update of Rainfall Intensity-Duration-Frequency Curves, Abu Dhabi Municipality – Stormwater and Subsoil Drainage Masterplan. (2014).

Halwatura, D. & Najim, M. M. M. Application of the HEC-HMS model for runoff simulation in a tropical catchment. Environ. Model. Softw. 46, 155–162 (2013).

Moriasi, D. N. et al. Model evaluation guidelines for systematic quantification of accuracy in watershed simulations. Trans. ASABE. 50, 885–900 (2007).

Nu-Fang, F., Zhi-Hua, S., Lu, L. & Cheng, J. Rainfall, runoff, and suspended sediment delivery relationships in a small agricultural watershed of the Three Gorges area, China. Geomorphology 135, 158–166 (2011).

Funding

This research was funded by National Water and Energy Center at United Arab Emirates University through the Asian University Alliance (AUA) program, grant number 12R176-AUA-NWEC-4-2023.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: I.R.K, S.I.E, R.R, Q.K, M.M.M; Data curation: I.R.K, S.I.E, R.R, Q.K; Formal Analysis: S.I.E, R.R, M.M.M; Funding acquisition: M.M.M; Investigation: I.R.K, R.R, Q.K; Methodology: I.R.K, Q.K, M.M.M; Project administration: R.R, M.M.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, I.R., Elmahdy, S.I., Rustum, R. et al. Floods modeling and analysis for Dubai using HEC-HMS model and remote sensing using GIS. Sci Rep 14, 25039 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74736-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74736-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Interpretable flash flood susceptibility mapping in Yarlung Tsangpo River Basin using H2O Auto-ML

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Remote sensing and climatic data for flood impact assessment in Al-Ain (UAE)

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Tropical-extratropical interactions: the atmospheric dynamics behind Dubai's extreme precipitation in April 2024

Natural Hazards (2025)

-

A Systematic Framework of Flash Floods Disaster-Causing Mechanisms in Ungauged Mountainous Micro-Watersheds: Case Study of Qialegeer Village, Xinjiang, China

International Journal of Disaster Risk Science (2025)

-

Land use change, planning instruments, and sustainable strategies for urban flood risk management in Ibadan, Nigeria

Discover Environment (2025)