Abstract

Observational studies have shown some association between cannabis use disorder (CUD) and neurological disorders, but their causal relationship is unclear. In this study, we tested the potential causal relationship between CUD and three common neurological disorders using two-sample Mendelian randomization (TSMR) and multivariate MR (MVMR) methods. Thirty-two genetic loci were extracted as exposure factors from the largest genome-wide association study (GWAS) summary statistics for CUD to date. TSMR results showed that genetic prediction of CUD with all stroke, ischemic stroke, large-artery atherosclerotic stroke, migraine with aura, and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) had a positive causal relationship (P < 0.05), which was not found in several other diseases. The association between CUD and stroke, ischemic stroke, and AD in the MVMR study may have been influenced by confounding factors (P > 0.05). Subgroup analyses highlighted a causal relationship between genetically predicted CUD and large-artery atherosclerotic stroke (OR = 1.169; 95%CI 1.030–1.328; P = 0.016) and migraine with aura (OR = 1.142; 95% 1.021–1.278; P = 0.020). Our further functional mapping and annotation enrichment analyses using FUMA suggest that the brain-gut axis may serve as another layer of explanation for the existence of an association between CUD and neurological disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the legalization of cannabis has gradually been applied in many regions, leading to the use of cannabis as the next most popular and most used psychoactive product in the world, after tobacco. However, in the long run, repeated heavy or chronic high dose use of cannabis often contribute to the development of cannabis use disorder (CUD)1,2. CUD as a heritable psychiatric disorder defined as a problematic pattern of cannabis consumption in which the user is unable to control cannabis use even though he or she is already experiencing severe physical and psychological impairment, and revised from the DSM-IV definition (Cannabis Dependence and Abuse) to include symptoms of tolerance and withdrawal3,4.

An association has been shown between CUD and certain neurological disorders, including Stroke, migraine and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Stroke, migraine and AD as major contributors to the overall burden of disease in Europe, Asia and other regions5,6. Among them, stroke, as a cerebrovascular disease with sudden onset of symptoms and clinical signs, has two pathological subtypes including ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage, with ischemic stroke including various subtypes such as large-artery atherosclerotic stroke, small-vessel stroke and cardioembolic stroke7. A series of studies has shown that heavy cannabis use is associated with an increased risk of stroke and its subtypes8,9,10. The latest advances in Mendelian randomization (MR) studies now show a positive causal association between CUD and stroke11. However, the contribution to its subtypes is unclear, and there may be differences in pathological mechanisms between subtypes.

Migraine is a genetically influenced disorder and is classified into subtypes such as migraine without aura and migraine with aura according to the International Headache Society’s classification criteria12. Cannabis affects the gray matter areas surrounding the midbrain efferent ducts and may reduce the incidence of migraine and its subtypes, even with long-term repeated cannabis use13,14, and there exists some belief that the onset of migraine may be due to a lack of endogenous cannabinoids, and a search did not reveal an exploration of the relationship between CUD and migraine.

AD, the most common cause of dementia, is characterized by a decline in memory, language and executive skills. People with CUD have reduced blood flow to every brain region and the resulting structural changes are long-lasting, with dysfunction of the hippocampus leading to an increased risk of developing AD15.

Although studies have examined whether CUD has an effect on the risk of developing stroke subtypes, migraine and its subtypes, and AD, clinical trials and related studies on CUD and the three diseases are still insufficient, and previous studies have been limited to observational studies, with some shortcomings and limitations in making causal inferences. This has raised concerns about whether CUD can have neurological effects. In order to further confirm whether CUD exists as a risk factor for the development of these three diseases, and that the treatment of CUD will potentially serve as a novel means of preventing the development of the three neurological disorders in clinical practice for the purpose of early prevention of the diseases, further studies are needed to clarify the causal relationship between the two, and therefore, we conducted the MR study. MR, an emerging epidemiological approach, uses genetic variation (i.e., single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs) to proxy intermediate phenotypes and provide evidence for a putative causal relationship between risk factors and disease16, and it has now been widely used in the study of pathogenesis.

Therefore, in this study, to explore in depth the causal associations between CUD and stroke subtypes, migraine and its subtypes, and AD, we adopted a two-sample MR analysis and used multivariate mendelian randomization (MVMR) methods to explore the influence of multiple confounding factors in it.

Methods

Study design

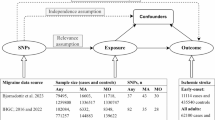

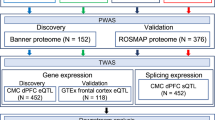

The present MR study consisted of two phases (Fig. 1), in the first phase, a two-sample univariate MR study was performed using summary statistics from a publicly available genome-wide association study (GWAS) of a population of European ancestry to assess the causal effects of CUD on three common neurological disorders. The MR study selected SNPs with strong correlations with intermediate phenotypes as genetic instrumental variables that had to satisfy the following three key assumptions16 shown in Fig. 1A: (1) genetic variation is associated with the exposure factor of interest (CUD); (2) genetic variation is not associated with any confounders of exposure and outcome associations; and (3) genetic variation does not directly affect outcome unless achieved through exposure. In the second phase, the MVMR model was constructed using multivariate MR analysis to adjust for possible confounders to determine the independent effects of CUD on the three neurological disorders (Fig. 1B).

Overview of the MR study design of the association between cannabis use disorder and three neurological disorders. (A) Univariate MR analysis and three key assumptions. (B) Multivariate MR analysis. AS, All Stroke; IS, Ischemic stroke; LAS, large-artery atherosclerotic stroke; SVS, Ischemic stroke (small-vessel); CES, cardioembolic stroke; ICH, Intracerebral Hemorrhage; AD, Alzheimer’s disease.

Data sources and selection of genetic instruments

In the present study, CUD was used as exposure and the study outcomes were three neurological disorders including all stroke, ischemic stroke, large-artery atherosclerotic stroke, small-vessel stroke and cardioembolic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, Migraine, Migraine with aura, Migraine without aura and AD. CUD’s GWAS summary statistics were obtained from the largest current meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of cannabis use disorders published in July 2020 17, which included 14,080 cases and 343,726 controls. The outcome data and confounding factors used to conduct this two-sample MR analysis were obtained from the IEU Open GWAS database (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/), a brief description and ID number for each phenotype is given in Table 1, and detailed information can be found in the Supplementary file, all in European large GWAS for all the above traits, mainly including effect estimates, standard deviations, p-values, effect and non-effect alleles, effect allele frequencies and their sample size.

Since only 2 SNP representative of CUD were obtained under the condition of genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10− 8), the threshold was relaxed in this study and a set of phenotypically associated genetic variants was extracted using P < 5 × 10− 6 as the threshold. To ensure that all SNPs were independent of each other in TSMR and MVMR, the linkage disequilibrium (LD) threshold was set to r2 = 0.001 and kb = 10,000. To avoid the impact of bias from potentially weak instrumental variables on the MR analysis, the F statistic was also used to measure the strength of association of each SNP with CUD, and the following equation was used to calculate the F statistic: F = (N-K-1)/K × R2/(1-R2), where N represents the sample size, K represents the number of SNPs, and R2 represents the extent of IV explained exposure18. R2 is calculated as follows: R2 = 2 × (1-MAF) × MAF × beta2, where MAF is the minor allele frequency, beta is an estimate of the phenotype for that SNP19. IVs with an F-statistic > 10 was eventually included in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

For univariate MR analysis, when a SNP was not available at the time of extraction in the ending, a proxy SNP was found in LDlink (https://ldlink.nci.nih.gov/) based on r2 > 0.8 instead. After extraction and strict data reconciliation, for the echo SNPs, we removed them. We further applied MR Steiger filtering to remove those SNPs that were more strongly correlated with the outcome than the exposure, and if we found SNPs with a result of “FALSE”, we removed them, which may lead to the possibility of reverse causality. Afterwards, data analysis was performed, and MR results were obtained using the inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method as the main analysis method, using multiple validity robust methods including weighted median method, penalized weighted median20, MR RAPS21 and IVW radial regression22 as sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the MR results. Then an additional series of sensitivity analyses were continued, firstly, Cochran’s Q test was executed to assess the heterogeneity of the IVW results. Second, to satisfy the exclusion restriction hypothesis when the MR key assumptions were met, the MR-Egger and MR PRESSO methods were used to perform a horizontal multiplicity test to determine the presence of horizontal multiplicity of MR results based on the intercept term in the MR-Egger regression, and when MR PRESSO detected an outlier, we excluded it as the SNP that produced the horizontal multiplicity and used Radial MR to complement the detection of outliers. A leave-one-out method was performed to see how each SNP affected the outcome. And the statistical efficacy was calculated using the web tool mRnd (http://cnsgenomics.com/shiny/mRnd/).

For multivariate MR analysis, to avoid potential confounders affecting the association between CUD and the three neurological disorders, and validated genetic tools were retrieved using PhenoScanner in order to find potential confounders previously reported to be associated with genetic tools23. A total of four phenotypes were found to be associated with (1) smoking, (2) alcohol consumption, (3) education, and (4) body mass index. The multivariate inverse variance weighting (MVMR-IVW) method was used as the main analysis method.

Enrichment analysis

To explore the potential link between CUD and three common neurological diseases at the molecular level, tissue expression enrichment analysis of genes was performed using FUMA24 for the obtained genes by retrieving the corresponding gene at each SNP site in the dbSNP database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/snp_summary.cgi). In FUMA’s GENE2FUNC module, we have used the default settings.

Results

We selected a total of 32 SNPs representing CUD as exposures for MR analysis, F-statistics of all included SNPs were > 10, and the details of the SNPs are listed in Table S1. One MR analysis was performed for each disease, and because the SNP or its proxy was not found in some endpoints, and after sensitivity analysis and MR Steiger filtering of MR results resulted in a different number of SNPs used in each MR analysis.

Univariate MR estimates of causal associations of CUD with three common neurological disorders

The causal associations of selected SNPs representing CUD in each group with three neurological diseases and their subtypes are shown in the forest plot in Fig. 2. The IVW results had evidence supporting that CUD increases all stroke (OR: 1.048; 95% CI: 1.004–1.094; P = 0.032), ischemic stroke (OR: 1.069; 95% CI: 1.022–1.118; P = 3.69 × 10− 3), large-artery atherosclerotic stroke (OR: 1.273; 95% CI: 1.142–1.419; P = 1.22 × 10− 5), migraine with aura (OR: 1.146; 95% CI. 1.038–1.264; P = 6.73 × 10− 3), and AD (OR: 1.091; 95% CI: 1.017–1.170; P = 0.015) for the risk of disease (Fig. 2), and the corresponding statistical power is shown in Table S2. Among the four methods in the supplement, the direction of effect was consistent with the IVW method, although the WM and penalised weighted median methods were not statistically significant in the all stroke, ischemic stroke and AD analyses (Table S3). However, CUD was not significantly associated with small-vessel stroke (OR: 1.017; 95% CI: 0.922–1.122; P = 0.731), cardioembolic stroke (OR: 1.076; 95% CI: 0.986–1.175; P = 0.099), Migraine (OR:1.048; 95% CI: 0.981–1.119; P = 0.165), migraine without aura (OR:1.092; 95% CI: 0.986–1.210; P = 0.092) and ICH (OR: 0.916; 95% CI: 0.609–1.378; P = 0.674) association.

Genetically predicted causal associations between CUD and neurological disorders. MR results where significant causal associations exist are indicated using light salmon pink colors and are bolded. MR results that are not causally causal associations are indicated in blue color. AS, All Stroke; IS, Ischemic stroke; LAS, large-artery atherosclerotic stroke; SVS, small-vessel stroke; CES, cardioembolic stroke; ICH, Intracerebral Hemorrhage; AD, Alzheimer’s disease.

Sensitivity analyses did not reveal heterogeneity or horizontal pleiotropy between CUD and all stroke, ischemic stroke, large-artery atherosclerotic stroke, small-vessel stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, Migraine, Migraine with aura, Migraine without aura, and AD (Table 2). The leave-one-out analysis revealed that no specific SNPs would have an effect on the outcome (Figure S1.1, Figure S1.2, Figure S1.3). In the MR Steiger filtering test of intracerebral hemorrhage results with AD, we found SNPs with “FALSE” results and excluded it (Table S4). MR PRESSO did not detect outliers in the MR analyses (Table S4), but certain analyses that did not pass the Radial MR test (including all stroke, ischemic stroke, large-artery atherosclerotic stroke, cardioembolic stroke, AD, Migraine, Migraine with aura, and Migraine without aura) had detected outliers (Figure S2.1, Figure S2.2, Figure S2.3).

Multivariate MR analysis of causal associations between CUD and three common neurological disorders

Considering the possible influence of four confounding factors in the MR causal association analysis of this study, we also performed a multivariate MR analysis to exclude as much as possible the effects of known confounders and to determine the direct effect of exposure on outcome, and the MVMR results are shown in Figs. 3, 4, and 5. Results of the IVW method showed that after adjusting for smoking, alcohol consumption, education, and BMI, the MR analysis of CUD with large-artery atherosclerotic stroke resulted in an OR: 1.169, 95%CI: 1.030–1.328, P = 0.016, and a causal relationship between CUD and large-artery atherosclerotic stroke remained, with CUD associated with an increased risk of developing large-artery atherosclerotic stroke. The result of the MR analysis of CUD and migraine with aura was OR: 1.142, 95%CI: 1.021–1.278, P = 0.020, showing that there was a statistically significant and still causal association between CUD and migraine with aura, and that CUD was associated with an increased risk of developing migraine with aura. The significant association between CUD on all stroke, ischemic stroke and AD disappeared after adjusting for four confounders: smoking, drinking, BMI and education. However, for small-vessel stroke, cardioembolic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, migraine and migraine without aura, a statistically significant association between CUD and diseases was still not found when adjusted for the MVMR model.

Forest plot of MVMR adjusted for smoking, alcohol consumption, education, and BMI for stroke and its subtypes. Colors indicate five exposures and are bolded for the main exposure CUD and marked red for MR results with significant causal associations. AS, All Stroke; IS, Ischemic stroke; LAS, large-artery atherosclerotic stroke; SVS, small-vessel stroke; CES, cardioembolic stroke; ICH, Intracerebral Hemorrhage;

Forest plot of MVMR adjusted for smoking, alcohol consumption, education, and BMI for migraine and its subtypes. Colors indicate five exposures and are bolded for the main exposure CUD and marked red for MR results with significant causal associations. CUD, cannabis use disorder; BMI, body mass index.

Enrichment analysis

The 30 tissues obtained from GTEx V8 were analysed for tissue-specificity analysis based on the genes corresponding to each SNP using the FUMA analysis platform. In this analysis, a total of 28 genomic loci were associated with CUD (Table S1), and our results showed that these 28 genes were significantly enriched in the colon (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6).

Discussion

In the present study, univariate and multivariate MR analyses were used to shed new light on the relationship between CUD and stroke and its subtypes, migraine and its subtypes, and AD. During the search, no investigational clinical trials or clinical practice studies were identified to investigate the relationship, suggesting that we filled a knowledge gap in this direction. (1) the evidence obtained supports a positive causal relationship between genetically predicted CUD and large-artery atherosclerotic stroke and migraine with aura, independent of the effects of smoking, alcohol consumption, body mass index, and education; (2) in contrast, the causal relationship between genetically predicted CUD for all stroke, ischemic stroke, and AD was attenuated after adjusting for smoking, alcohol consumption, body mass index, and education; and (3) it was not observed that CUD was associated with the risk of developing several other diseases.

Our MR findings on CUD and stroke produce inconsistent results with previous epidemiologic studies. In a general population survey of different age groups in the Australian population9, the prevalence of stroke among cannabis users was found to be elevated despite frequent long-term use and when confounding factors such as smoking were excluded, suggesting that CUD exists independently of smoking as a risk factor for stroke. In Brandon’s retrospective cohort study of national inpatients from 2006 to 2015 25, CUD patients were found to be associated with an increased incidence of stroke. In a recent MR study of CUD and stroke where causality could be established11, a statistically significant causal relationship was found even after adjusting for potential confounders, however, our study used the most current GWAS summary statistics for the European population with stroke disease, which is different from previous MR studies in that after adjusting for confounders, the statistical relationship disappeared, which may appear as a new addition to remind us of the differential risk of the disease in different pedigree populations.

In a case-control study of urinary cannabis screening in 160 patients with ischemic stroke, the significant association between cannabis use and ischemic stroke was found to be absent after adjusting for tobacco26, In another case-control study containing a sample of 214 cases27, an association between cannabis use and ischemic stroke was found, controlling for other risk factors. In response to the above controversy regarding the relationship between cannabis use and ischemic stroke, our study supports the first conclusion, on the basis of which we found that the association may also be influenced by alcohol consumption, education and BMI.

The underlying mechanisms of the effects of CUD on the development of ischemic stroke are unknown, and more than 60 cannabinoids have been previously reported to have a propensity to damage arteries28, that findings from a cohort study with up to seven follow-ups over a 25-year period suggest that cumulative exposure to marijuana may be associated with the development of atherosclerosis, cannabis smokers have an independently increased risk of abdominal arterial calcification and coronary artery calcification scores29, and the recently published literature also arrives at a consistent view30. In a recent cross-sectional study including nearly 700 young adults with first-ever ischemic stroke, daily or frequent cannabis use was found to be significantly associated with the phenotype of large-artery atherosclerotic stroke31. This was further confirmed in the present MR study and the relationship was not affected by known confounders (smoking, alcohol intake, BMI, and education). This also suggests that marijuana use may accelerate atherogenesis, which provides evidentiary support for the previous ambiguities regarding the relationship between marijuana use and atherosclerosis.

The present study found no statistically significant effect of CUD on migraine, but a causal relationship between it and subtypes, which is inconsistent with Russo’s findings and preclinical and clinical evidence that endogenous cannabinoid deficiency leads to lower pain thresholds, which in turn leads to migraine32, and play a role in the development of migraine. At the same time, our study found that the causal relationship between CUD and migraine with aura persisted, excluding the influence of confounding factors. Thus, different migraine subtypes may have different effects on the therapeutic effects of overdose cannabis than medical cannabis, i.e., the occurrence of migraine and its subtypes may be dose-related. In a study of 1055 psychoactive substance abusers treated over a 10-month follow-up period33, prolonged cannabis use was found to lead to an increased incidence of migraine. The search revealed few studies exploring the association between cannabis use or CUD and migraine and its subtypes, which also suggests that we provide new ideas in this regard, which also requires further practice in the clinic to explore whether there is an association between the two after excluding confounding factors.

In observational studies, the correlation between CUD and AD is inconsistent. According to previous studies, attention deficit disorder can be prevented by promoting hippocampal neurogenesis through smoking marijuana34. But another study says that overdose will lead to hippocampal atrophy and poor cognitive function, and that mild cognitive deficits and hippocampal atrophy at midlife are risk factors for advanced dementia35. This also suggests that the dose of cannabis use may have an incremental harmful effect on the developmental process of AD. However, the findings of an umbrella review suggest that marijuana use is not associated with the risk of developing AD36. Our study found that the causal relationship between CUD and AD disappeared after further adjusting for potential confounders, which supports the results of the review but is inconsistent with the results of previous studies, suggesting that the clear causal relationship between CUD and AD may be affected by confounders.

Enrichment analysis revealed that differential genes were primarily enriched in the colon, a tissue thought to interact with the brain (gut-brain-microbiome, GBM)37. The endogenous cannabinoid system can be specifically dysregulated by heavy cannabis use38. In turn, it acts as an important regulator of the brain-gut axis, which usually acts as an inhibitor of neural activity in pathways regulated by the gastrointestinal physiology39. This provides another layer of evidence linking CUD to three common neurological disorders.

There are several main advantages of our study. First, causality determination is difficult to achieve in clinical practice because of the large sample size required and the ethical and moral standards to be met. This clearly sets off the significant advantages of MR, which is based on a large sample for analysis and discussion, and achieves to complement the existing gaps in the relationship between CUD and common neurological disorders. Second, multiple sensitivity analyses were performed to validate our MR results and reverse causality was excluded to ensure the robustness of the results. Third, the MVMR method was used to determine the independent effect of CUD on outcome, effectively avoiding confounding bias. Fourth, the statistical validity of this study further provides firm support for the MR results of our analysis.

However, we should also acknowledge some potential limitations. First, this study included a population of European ancestry, which may limit generalization to other populations. Second, the use of a looser threshold (P < 5 × 10− 6) to screen for IVs identifying CUD may have led to an increase in invalid IVs, although the F-statistic, MR-RAPs, and MR-IVW-Radial methods did not support the presence of this bias. Third, the disappearance of univariate detected causal associations after multivariate testing, which we believe may occur because the CUD GWAS summary statistics used in this study, even though they are currently up to date, may have resulted from the fact that the number of cases included in this GWAS data was not sufficient for CUD as a secondary exposure.

In conclusion, our findings provide more reliable evidence for clinical practice that the impact of relevant confounding factors should be considered before performing disease analysis in people addicted to smoking or cannabis with three common neurological disorders and their subtypes. It also exemplifies that further exploration of disease subtypes in search of etiology is crucial, as different pathologic mechanisms may be responsible for different disease subtypes from one another.

Data availability

All data used in this study are previously published publicly downloadable GWAS summary statistics available in the article/supplementary material.

References

Connor, J. P. et al. Cannabis use and cannabis use disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 7, 16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-021-00247-4 (2021).

Chen, D., Wang, X., Huang, T. & Jia, J. Genetic support of a causal relationship between cannabis use and educational attainment: A two-sample mendelian randomization study of European ancestry. Addiction. 118, 698–710. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16090 (2023).

Hasin, D. S. et al. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5 Cannabis Use Disorder, 2012–2013: findings from the national epidemiologic survey on Alcohol and related Conditions-III. Am. J. Psychiatry. 173, 588–599. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15070907 (2016).

Robinson, T. et al. Identifying risk-thresholds for the association between frequency of cannabis use and development of cannabis use disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 238, 109582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109582 (2022).

Kang, S. et al. Burden of neurological diseases in Asia from 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis using the global burden of Disease Study data. BMJ Open. 12, e059548. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059548 (2022).

Deuschl, G. et al. The burden of neurological diseases in Europe: An analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Public. Health. 5, e551–e567. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(20)30190-0 (2020).

Hankey, G. J. & Stroke Lancet 389, 641–654. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(16)30962-x (2017).

Hackam, D. G. Cannabis and stroke: Systematic appraisal of case reports. Stroke. 46, 852–856. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.115.008680 (2015).

Hemachandra, D., McKetin, R., Cherbuin, N. & Anstey, K. J. Heavy cannabis users at elevated risk of stroke: Evidence from a general population survey. Aust N Z. J. Public. Health. 40, 226–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12477 (2016).

Phillips, K. T. et al. Chronic health conditions, acute health events, and healthcare utilization among adults over age 50 in Hawai’i who use cannabis: A matched cohort study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 234, 109387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109387 (2022).

Chen, M., Lu, Y. L., Chen, X. F., Wang, Z. & Ma, L. Association of cannabis use disorder with cardiovascular diseases: A two-sample mendelian randomization study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 966707. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.966707 (2022).

Pescador Ruschel, M. A. & De Jesus, O. In StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC. (2023).

Welch, K. M., Nagesh, V., Aurora, S. K. & Gelman, N. Periaqueductal gray matter dysfunction in migraine: Cause or the burden of illness? Headache. 41, 629–637. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.041007629.x (2001).

Cuttler, C., Spradlin, A., Cleveland, M. J. & Craft, R. M. Short- and long-term effects of cannabis on headache and migraine. J. Pain. 21, 722–730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2019.11.001 (2020).

Amen, D. G. et al. Discriminative properties of hippocampal hypoperfusion in Marijuana users compared to healthy controls: Implications for Marijuana Administration in Alzheimer’s dementia. J. Alzheimers Dis. 56, 261–273. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-160833 (2017).

Davies, N. M., Holmes, M. V. & Davey Smith, G. Reading mendelian randomisation studies: A guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. Bmj. 362, k601. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k601 (2018).

Johnson, E. C. et al. A large-scale genome-wide association study meta-analysis of cannabis use disorder. Lancet Psychiatry. 7, 1032–1045. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(20)30339-4 (2020).

Pierce, B. L., Ahsan, H. & Vanderweele, T. J. Power and instrument strength requirements for mendelian randomization studies using multiple genetic variants. Int. J. Epidemiol. 40, 740–752. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyq151 (2011).

Burgess, S., Davies, N. M. & Thompson, S. G. Bias due to participant overlap in two-sample mendelian randomization. Genet. Epidemiol. 40, 597–608. https://doi.org/10.1002/gepi.21998 (2016).

Rees, J. M. B., Wood, A. M., Dudbridge, F. & Burgess, S. Robust methods in mendelian randomization via penalization of heterogeneous causal estimates. PLoS One. 14, e0222362. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222362 (2019).

Zhao, Q., Wang, J., Hemani, G., Bowden, J. & Small, D. S. Statistical inference in two-sample summary-data Mendelian randomizati on using robust adjusted profile score. http://arxiv.org/abs/1801.09652 [stat.AP,math.ST,stat.TH,65J05, 46N60, 62F35].

Hemani, G., Bowden, J. & Davey Smith, G. Evaluating the potential role of pleiotropy in mendelian randomization studies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 27, R195–r208. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddy163 (2018).

Staley, J. R. et al. PhenoScanner: A database of human genotype-phenotype associations. Bioinformatics. 32, 3207–3209. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btw373 (2016).

Watanabe, K., Taskesen, E., van Bochoven, A. & Posthuma, D. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat. Commun. 8, 1826. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01261-5 (2017).

McGuinness, B. et al. Cannabis use disorder and perioperative outcomes in vascular surgery. J. Vasc Surg. 73, 1376–1387.e1373 (2021).

Barber, P. A. et al. Cannabis, ischemic stroke, and transient ischemic attack: A case-control study. Stroke. 44, 2327–2329. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.113.001562 (2013).

Kaku, D. A. & Lowenstein, D. H. Emergence of recreational drug abuse as a major risk factor for stroke in young adults. Ann. Intern. Med. 113, 821–827. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-113-11-821 (1990).

Desai, R. et al. Prevalence and impact of cannabis use disorder on acute ischemic stroke and subsequent mortality in elderly peripheral vascular disease patients: a population-based analysis in the USA (2016–2019). Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 49, 102162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2023.102162 (2024).

Auer, R. et al. Lifetime marijuana use and subclinical atherosclerosis: the coronary artery Risk Development in Young adults (CARDIA) study. Addiction. 113, 845–856. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14110 (2018).

Subramaniam, V. N., Menezes, A. R., DeSchutter, A. & Lavie, C. J. The Cardiovascular effects of Marijuana: Are the potential adverse effects Worth the High? Mo Med. 116, 146–153 (2019).

Gueyraud, G. et al. Stroke phenotype in cannabis users among young adults with ischemic stroke. Eur. J. Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.15799 (2023).

Russo, E. B. Clinical Endocannabinoid Deficiency reconsidered: current research supports the theory in Migraine, Fibromyalgia, irritable bowel, and other treatment-resistant syndromes. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 1, 154–165. https://doi.org/10.1089/can.2016.0009 (2016).

Beckmann, Y. Y., Seçkin, M., Manavgat, A. & Zorlu, N. Headaches related to psychoactive substance use. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 114, 990–999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.02.041 (2012).

Calabrese, E. J. & Rubio-Casillas, A. Biphasic effects of THC in memory and cognition. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 48, e12920. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.12920 (2018).

Meier, M. H. et al. Long-term Cannabis Use and Cognitive reserves and hippocampal volume in midlife. Am. J. Psychiatry. 179, 362–374. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21060664 (2022).

Arango, C. et al. Risk and protective factors for mental disorders beyond genetics: An evidence-based atlas. World Psychiatry. 20, 417–436. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20894 (2021).

Mayer, E. A., Nance, K. & Chen, S. The gut-brain Axis. Annu. Rev. Med. 73, 439–453. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-042320-014032 (2022).

Martin, E. L. & McRae-Clark, A. L. Evidence for the endocannabinoid system as a therapeutic target in the treatment of cannabis use disorder. Curr. Addict. Rep. 7, 545–552. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-020-00342-8 (2020).

Sharkey, K. A. & Wiley, J. W. The role of the endocannabinoid system in the brain-gut axis. Gastroenterology. 151, 252–266. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.04.015 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Finngen study. We would like to thank the participants and investigators of the MEGASTROKE consortium, the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, GWAS and Sequencing Consortium of Alcohol and Nicotine use, Social Science Genetic Association Consortium, and the International Genomics of Alzheimer’s Project for providing the GWAS summary statistics.

Funding

This research was funded by S&T Promotion Project of Health Commission in Jilin province China, Grant number 2022JC082, and S&T Development Plan Project in Jilin Province China, grant number 20220203125SF.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made significant contributions to the article and read and approved the final manuscript. L.D. designed the overall study design as well as acquired, organized, and analyzed the data and wrote the article. M.T.X. investigated the study and downloaded, organized, and analyzed the data for validation. W.Z.L., M.Z., and L.J.Y. organized and analyzed the data validation and methodology. Q.Y., Y.C.Z., and X.Y.L. are responsible for study design, project administration, access to funding and supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, L., Xie, M., Li, W. et al. Cannabis use disorder increases risk of large-artery atherosclerotic stroke and migraine with aura through mendelian randomization study. Sci Rep 14, 24295 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74754-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74754-1