Abstract

This study introduces an approach to validate sampling points for air monitoring in environments where operations generate significant airborne particulate radioactivity. A case study of repair works in a nuclear spent fuel reprocessing facility is used to synthesis and demonstrate the methodology. We use the probability distribution of air activity measurements and the correlation between two sampling points near high particulate generating operations and the ventilation ducts. The methodology developed in this paper can be applied in task-related air monitoring scenarios for validation of sampling points. This will augment internal exposure control measures during works involving physical entries in areas with high potential of escalation of air activity (e.g., during major repairs, during decommissioning of nuclear facilities etc.) and to evaluate the sufficiency of respiratory protection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the “Declaration to Triple Nuclear Energy” at COP281, more than 20 countries recognized the key role of nuclear energy in achieving global net-zero greenhouse gas emissions and to get closer to the 1.5 °C limit on temperature rise. The impetus behind this declaration is the urgent search for energy resilience and decarbonization of energy. Unlike other zero-carbon energy options like solar and wind energy that provide an intermittent energy supply, nuclear energy has proved to be a reliable and safe source of dispatchable energy2. It is also the only zero-carbon option that works for high-temperature core industrial processes, such as steel production.

Nuclear fuel cycle facilities (which include uranium mines, nuclear power plants, spent fuel reprocessing facilities and nuclear waste management facilities) have an excellent track record in controlling exposures (and hence the risk) from ionizing radiation to its workers and to the public. For perspective, the average annual effective dose to occupational workers at nuclear reactors across the world between 2010–2014 was 0.5 mSv, compared to 4.1 mSv between 1975–793. In a 20-year study on radiological impact of Indian nuclear power plants on the environment, it was found that the estimated total radiation doses to the public were at most 10% of the stipulated regulatory dose limit to public (1000 μSv) and consistently decreased over the study period4.

Despite these advantages, if nuclear industry is to scale up to the energy demands of the mid-21st century, the industry has to implement best practices learned from individual-projects. This can reduce the likelihood of cost and schedule overruns5. And to do so, will require optimization in every aspect of the industry.

Like any other industry, operational downtime in a nuclear facility, especially nuclear power plants and fuel cycle facilities have to be minimized to increase the production output. Maintenance and repair in a nuclear facility is a non-trivial task, with the usual technical difficulties exacerbated by considerations of radiation exposure to the workers. By design, nuclear facilities have equipment that require no or minimal physical entries inside areas with high radiation fields and transferable radio-contamination. However, in certain scenarios (e.g., the case study of a spent nuclear fuel reprocessing facility that we present in this paper), entry of workers in such areas is unavoidable. In such scenarios, radiation exposure control measures have to be extensive, and informed by workplace monitoring instruments, thus expanding the monitoring requirements.

Workplace monitoring practices can be divided into three major categories–routine monitoring (to demonstrate that radiation environment in the workplace is satisfactory), task-related monitoring (in scenarios where monitoring data are required to continuously inform ALARA decisions) and special monitoring (investigative monitoring done with the objective to obtain additional exposure information)6. This categorization is in addition to the an even broader classification on the basis of monitoring for external exposure and internal exposure. The prevalent monitoring practice for external exposure is by real-time measurement of \(H^*(10)\) through area gamma monitors (AGMs), and measurement of \(H_p(10)\) through personal dosimeters. For internal exposure, the monitoring of airborne particulate radioactivity concentration through air sampling is the prevalent practice, along with internal dose assessment techniques through in-vivo and in-vitro samples.

Specifically for monitoring of airborne particulate radioactivity (APR) concentrations, nuclear facilities usually have continuous air monitors (CAMs) installed in locations with potential of release of air activity beyond the designed containment. The purpose of these CAMs is to provide an immediate alarm (audio-visual) to alert radiation workers of elevated airborne radioactivity. These CAMs sample air, and pass it through a medium (a filter paper for particulate radioactivity, usually glass fibre filters). The radioactivity collected on these filter papers (FPs), are measured in real-time by an alpha or beta detector, depending on the radionuclide of interest. The activity measured in real-time, however, is not an accurate representative of airborne particulate radioactivity because of the contribution of short-lived natural radioactivity collected on the FPs. After a set sampling schedule (usually after 24 h of sampling, or less in case of an alarm-event), the FPs of CAMs are changed, and counted after a 4-day delay, to allow for the decay of natural radioactivity. Finally, based on these counts, air activity is estimated for the surveilled area in terms of Derived Air Concentration (DAC) of radionuclide of interest. Thus, CAMs serve the purpose of both monitoring (systematic, ongoing process of measuring and recording data) and surveillance7 (a more focused observation aimed at early detection of unusual conditions or changes from the norm. For example, trend analysis of airborne particulate radioactivity can be used to draw conclusions about the integrity of radioactive handling equipment and engineered safety measures to control the airborne contamination8).

However, there maybe instances where surveillance for air activity goes beyond the purview of CAMs installed for routine monitoring (e.g., during maintenance shutdowns or extensive repairs or during decommissioning of nuclear facilities). These works may involve entries of radiation workers in areas with high air activity concentration. The goal in such scenarios will be to ensure the sufficiency of respiratory protection. For such scenarios, the assigned protection factor (APF)9 of the recommended respirators should be higher than the DAC value in the work areas. In such scenarios, special monitoring of air activity, by installation of additional CAMs is necessary.

In such cases the APR concentrations are envisaged to escalate. Hence, it becomes necessary to consider the position of the sampling point of air monitors near the working area. A sampling point too near the APR-generating operation may not be desirable as it creates the additional hazard of handling highly active filter papers. And a sampling point too far away will not serve the purpose either, since the observations from such a sampling point may not capture the underlying physical process that generates APR (e.g, cutting and welding of radioactive fluid lines or equipment). Such repair works are protracted, with extensive considerations given to ensure that exposures to workers are well-controlled. A considerable part of procedural planning is dedicated to ALARA practices. Hence, the efforts of operational health physicists cannot be sufficiently directed at experimenting with different sampling locations. The practical considerations of positioning CAMs near APR-generating processes are necessary for effective monitoring. Positioning the CAM too close to the source may lead to excessively high radioactivity levels (a mix of artificial and natural) being collected, which could off-scale the detector and compromise the ability to monitor real-time changes in APR effectively. Conversely, placing the CAM too far from the source may result in insufficient detection of APR due to the influence of ventilation patterns rather than the actual APR-generating process. A detailed analytical model, by considering the aerosol generation process is possible, however, making a model flexible enough to be applicable across a wide variety of APR-generating scenarios maybe intractable. To address this, we propose a simpler method, more suited to the operational aspects of radiation protection.

In this work, we present an approach for validation of sampling points near high-APR generating operations (near the working area). We demonstrate this approach by presenting a case study of in-cell repair works at a spent fuel reprocessing facility. These repairs were part of a 3-year operational shutdown, with a quantum of work involving cutting, grinding and welding of process fluid lines of thermosyphon waste evaporators .These works were APR-generating operations, since the process fluid lines were highly radioactive, handling \(\beta \gamma\) activity concentration in the range of 4000–7000 TBq/m3 (~100–200 Ci per liter) during normal operations. In our approach, we estimate the probability density function for air activity near the working area and compare it with the density function near the ventilation duct of the area. We demonstrate that inferences from such a comparison can be used for validation of the sampling point near the working area, and thus the reliability of the special air monitoring.

Background of the case study

The data used in this work is from special monitoring for air activity during replacement of heat exchangers (HXs) of thermosyphon evaporators (TSEs) of a spent nuclear fuel reprocessing plant (from here on referred to as the facility).

This was a protracted repair work, spread over 3 years, and across three process cells (referred to as Cell-1, Cell-2 and Cell-3). Different process cells in the facility had different categories of evaporators. TSEs are used for volume reduction of high (with \(\beta \gamma\)-activity concentration greater than 3700 MBq/m3) and intermediate level liquid waste (with \(\beta \gamma\)-activity concentration between 37 MBq/m3 and 3700 MBq/m3) generated in different steps of PUREX process10 (this is a simplification since evaporators have other utilities in the PUREX process too. However, in the context of this work, such a simplification will suffice). The TSEs have shell and tube HX, with steam input on the shell side and radioactive process fluid on the tube side. As the process fluid absorbs heat (HX temperature ~105 °C), its temperature rises, and upon reaching its boiling point, it begins to vaporize. This phase change occurs within the tube side, allowing for the separation of vapor from the liquid. The resulting vapor is directed towards the off-gas system, while the concentrated liquid is collected in the concentrate tank, effectively achieving volume reduction.

Specifically for evaporator systems, corrosion and erosion are generally more severe compared to other types of equipment in PUREX process. This is because of (a) necessary concentration differences for evaporator operation, (b) frequent presence of solids in suspension and (c) high velocity of vapours and liquid11. Within the evaporator system the components of the evaporator that are exposed to severe thermal cycles and radiochemical elements, are the tubes of the HX. Eventually, during the course of their operations, the tubes of HXs fail, which can be addressed only through replacement of the failed HX.

Replacement of HXs in the facility (from hereon referred to as “in-cell works”) was possible only through physical entries inside the process cells. All the process fluid lines connecting the HXs to the TSEs were first cut. This was followed by edge-preparation, that involved grinding the edges smooth for welding. And finally, new HXs were welded to the TSE. Considering that the process fluid lines handled liquids with \(\beta \gamma\) activity concentration in the range of 4000–7000 TBq/m3 (~100–200 Ci per liter), controlling the external and internal exposures of the radiation workers were challenging.

The comprehensive exposure control measures implemented during the in-cell works are beyond the scope of this paper. However, we will delineate on the requirement for additional air activity surveillance.

Special monitoring for air activity

Process cells, being Red Zones during regular operations, are not part of routine air monitoring. According to general safety guidelines on occupational radiation protection12, the frequency of routine monitoring at a workplace should be commensurate with the occupancy factor of radiation workers in the location and the anticipated changes in the radiation environment. Because of the nature of the in-cell works, it was expected that in addition to the presence of transferable contamination in the work areas, there will be generation of particulate radioactivity during the in-cell works. Hence, it was deemed necessary to monitor changes in the APR concentrations in real-time (through direct readings from filter paper facing \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) detectors in CAMs), in addition to the estimation of air activity (in terms of DAC-h). To achieve this, a special air monitoring scheme was planned (shown in Fig. 1).

Key | Description |

|---|---|

1 | HEPA filter for local exhaust system |

2 | Centrifugal pump for local exhaust system |

3 | Sampling point for airborne radioactivity near working area (NWA) |

4 | Sampling point for airborne radioactivity near cell ventilation (NCV) Duct |

5 | Continuous air monitors (CAMs) for sampling points 3 and 4. Both \(\alpha\)-CAM and \(\beta\)-CAM are in the same housing, and connected to the central radiation protection console (CRPC) |

6 | Cell ventilation system |

7 | Plant ventilation system |

8 | Local exhaust system discharge to adjacent process cell |

Every process cell has a ventilation system by design. However, an additional local exhaust system was installed to increase the number of air changes. The suction of the local exhaust system was near the working area and the discharge point was near cell ventilation duct of an adjacent process cell (see “8” in Fig. 1.). The primary objective of this special air activity monitoring was to identify sudden increases in the APR concentrations near the working area. This was necessary to inform the sufficiency of air respirators and future protection protocols (this monitoring was in addition to the air monitoring using personal air samplers in the breathable zone of the workers).

It was obvious that the sampling point near working area (NWA) was to be suitably near the APR-generating operations. However, considering the protracted nature of the in-cell repair works, with the quantum of jobs insides the process cells being high-APR generating operations (cutting, welding, edge-preparation etc.), we needed to verify the ‘validity’ of sampling point NWA. Validity in this context is for the sampling point is its efficacy in capturing the suddent increases in APR concentration NWA. Thus, the CAM near working area should be able to capture the underlying physical processes generating APR. Reliability of the APR estimations from the sampling point NWA (see “3” in Fig. 1).

We achieved this by installing a second CAM near the process cell ventilation duct (NCV). These CAMs were connected to the Central Radiation Protection Console (CRPC) for real-time monitoring of air activity inside the cell. The CAM with sample point near working area (CAM-NWA) was an \(\alpha\)-CAM with a ZnS(Ag) detector near the filter face, and the CAM near cell ventilation duct (CAM-NCV) was a \(\beta\)-CAM with an end-window GM Tube.

Source of APR data

Since this was not part of routine monitoring, the schedule for filter paper changing was not fixed. Fresh filter papers were placed in the CAMs at the beginning of physical entries inside process cells, and were changed after physical entries inside the cells were suspended for the day. Every time the filter papers were changed, the sampling time was noted. After a delay of 4-days, to allow for decay of natural radioactivity, these filter papers were counted (for gross \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\)). Allowing for a 4-day delay before measurements of gross \(\alpha\) and gross \(\beta\) is an established practice in occupational radiation protection. This is because, in typical cases, CAMs are installed in nuclear facilities not to precisely quantify APR but to monitor changes (increases) in APR during normal operations. Changes in APR concentration indicate deviations from usual operations and are used as indicators of malfunctions in engineered safety measures (such as ventilation and containment) or deviations from safe operating procedures. In these situations, the concentration of artificial radionuclides in the air changes. The same was true in our case study–operations such as cutting, grinding, and welding of radioactive lines in the PUREX process were expected to release artificial APR. The sampling point of CAM-NWA was to be validated to determine if it could identify sudden changes in APR concentration. Therefore, 4-day delayed measurements of filter papers help identify trends in artificial radionuclides.

The sampling time and gross counts were used to calculate the derived air concentration-hours (DAC-h) inside near working area and near cell ventilation. For the purpose of analysis in this paper, we have retained DAC-h, instead of DAC, for two reasons - (1) Since DAC and DAC-h are related by a multiplicative factor, the distribution and correlation between NWA and NCV will not get affected by the choice of either DAC or DAC-h, (2) DAC-h is a normative term for expressing concentration in operational radiation protection because of its benefits over DAC13.

DAC-h(\(\beta\)) and DAC-h(\(\alpha\)) were calculated on the basis of annual limit intakes (ALIs) for the most limiting radionuclides in this monitoring scenario. The Minimum Detectable Activity (MDA) of the counting system was \(3\times 10^{-2}\) DAC-h(\(\alpha\)) and \(2\times 10^{-4}\) DAC-h(\(\beta\)).

The air activity observations (in DAC-h (\(\alpha\)) and DAC-h (\(\beta\))) were normalized (min-max scaling), with the goal to re-scale the air activity observations between 0 and 1.

where, \(x_{\text {min}}\)is the minimum air activity reading observed. This was 0 for our dataset (readings below MDA), \(x_{\text {max}}\) is the maximum air activity reading observed. This varied depending on the dataset. There are 12 distinct data sets (viz., observations from two CAMs, three process cells and \(\alpha\) & \(\beta\) observations).

The data used in this paper for analysis and calculations are the DAC-h(\(\alpha\)) and DAC-h(\(\beta\)) for CAM-NWA and CAM-NCV, along with the dates on which these observations were recorded. Table 1 shows a snippet of our dataset. Notice that \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) activities have been shown for both CAM-NWA (\(\alpha\)-CAM) and CAM-NCV (\(\beta\)-CAM). This is because the difference between CAM-NWA and CAM-NCV in the context of monitoring is only by the type of detectors they have. While the real-time readings, as captured by CRPC, for CAM-NWA were only for \(\alpha\)-activity and for CAM-NCV were for \(\beta\) activity, the filter papers from both the CAMs were measured for both gross \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) activity. These measurements were ultimately used to calculate DAC-h (\(\alpha\)) and DAC-h (\(\beta\)).

The blank cells (e.g., 03-10-2021) were for the days in which no in-cell works were done (i.e., there was no air activity surveillance inside the process cell). We made no attempts to impute these missing values because a timeseries analysis was not our objective. Observations below the MDA were assigned 0. Our distribution and correlation analysis was based on 706 such observations, with the half the observations for CAM-NWA and the other half for CAM-NCV.

The proposed validation methodology

The central hypothesis of our methodology is - if the sampling point for CAM-NWA were to be suitable for special air monitoring in a high-APR generating environment, then the probability distribution of activity deposited on the filter paper for CAM-NWA, should be similar to that of CAM-NCV. Furthermore, we expected them to be correlated because the underlying physical process for the observations (i.e., cutting, welding etc. of active fluid lines) in both the CAMs were same. We investigate these aspects of the air activity data from our case study by plotting the kernel density estimates and by calculating the Pearson’s correlation between the air activity from CAM-NWA and CAM-NCV.

Kernel density estimation

Kernel density estimation (KDE), is an established practice to estimate the underlying density function of a dataset14. A detailed tutorial on KDE can be found in15. KDE is a non-parametric method16 (i.e., it does not assume that the data fits any specific parametric form or distribution) for estimating density. Unlike histograms that use discrete bins, in KDE, the observations are smoothed using a Gaussian kernel.

Definition

For \(X_1,X_2,\dots ,X_n \in \mathbb {R}^d\) be an independent, identically distributed random sample from an unknown distribution P with density function p. In the context of this study, \(d = 1\), since air activity observations from each CAM are 1-dimensional. Formally, KDE is expressed as:

where,

- \(K: \mathbb {R}^d \longrightarrow \mathbb {R}\):

-

is the kernel function,

- \(h > 0\):

-

is the smoothing bandwidth that controls the extent of smoothing.

KDE plots

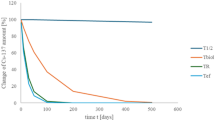

In this study, we have used KDE to analyze the similarity/dissimilarity of distribution of air activity data from CAM-NWA and CAM-NCV. The kernel density estimator (KDE) plots for air activity inside Process Cells are shown in Fig. 2. These plots are done using an open-source python library, seaborn17. The kernel function K(x) (in Eq. 2) used in this library is the Gaussian kernel.

The KDE is implemented using a Gaussian kernel, which smooths the data points over a continuous range. This smoothing is controlled by a bandwidth parameter, which affects the density estimator’s bias and variance. The choice of bandwidth is critical–too narrow a bandwidth leads to a plot that is too rough, with many spurious features resembling noise; too wide a bandwidth over-smooths the data, thus obscuring important structural details of the distribution. In seaborn bandwidth selection is optimized based on Silverman’s “rule of thumb”18.

where,

- \(\hat{\sigma }\):

-

is the standard deviation of the observations for which probability distribution is being estimated,

- n:

-

is the number of observations

Since our air activity observations were expected to be skewed (not every repair work inside the process cell was expected to generate appreciable quantity of air activity), instead of \(\hat{\sigma }\), a parameter A was used,

where,

- IQR:

-

is the interquartile range. \(IQR = Q_3 - Q_1\). \(Q_3\) is median of n/2 largest values in the dataset, and \(Q_1\) is the median of n/2 smallest values in the dataset. n can be even or odd. \(Q_2\) is median, by definition.

Silverman’s rule is designed to minimize the mean integrated squared error, providing the bandwidth of choice in many practical scenarios.

The KDE plots for \(\hat{p}_n(x)\) thus generated provide a visual representation of the air activity data’s distribution, allowing for direct comparison between the activity levels at the two sampling points. By examining these plots, we can infer whether the sampling locations consistently capture the representative air activity generated during operations. This visual and quantitative analysis forms the basis for validating the effectiveness and placement of air sampling points in high particulate-generating scenarios.

Figure 2 shows the kernel density estimates for air activity (\(\alpha\) and \(\beta\)) in different process cells for our case study.

Correlation matrix

Correlation heatmap for \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) activities for CAM-NWA and CAN-NCV. The numbers in the map are the Pearson’s correlation between observations. For example, in the “correlation matrix for Cell-3”, the number in the cell for DAC-h (alpha)-NWA and DAC-h (beta)-NCV is the correlation between the \(\alpha\) air activity recorded by CAM-NWA and CAM-NCV. A higher correlation denotes a stronger linear relationship. Unscaled observations were used to calculate these correlations.

We also calculated the Pearson correlation19 (also called Pearson product-moment correlation) of air activity observations for both \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) activities and for both near working area (NWA) and near cell ventilation (NCV) CAMs. The correlation matrices for these four variables are shown in Fig. 3 for three different process cells. A higher correlation between x and y indicates a linear relationship between two variables . A correlation of 1 would mean that x and y can be modelled as \(y = ax +b\).

Inferences

Based on the KDE plots (Fig. 2) and correlation matrices (Fig. 3), the following inferences were drawn:

Similarity in probability distribution functions for activity near the working area and near cell ventilation

The observed similarity in the probability distribution functions, which is most prominent in the (\(\alpha\))-air activity KDE plots for Cell-3 (Fig. 2), indicates that the underlying physical process responsible for generating the particulate activity during the repair work was consistent across the sampled locations, specifically CAM-NWA and CAM-NCV. This suggests that our chosen sampling location (i.e., that of CAM-NWA) effectively captured the airborne activity generated during in-cell operations. If this location was not well-chosen, the KDE plots for the working area and those near the cell ventilation (which is located much further away from the working area) would likely have shown significant differences. The similarity in these plots implies that the data from both locations reflects the same physical phenomena.

While the \(\beta\) activity distributions for Cell-3 and Cell-2 show some differences between the working area and the cell ventilation, the distributions for Cell-1 are almost identical. This consistency in Cell-1 can be attributed to the lower inventory of beta-emitting materials in Cell-3 and Cell-2 by the design of the PUREX process.

Wider activity distribution near working area compared to near cell ventilation

It was observed for Air activity (\(\alpha\)) distribution in Cell-3 and Air Activity (\(\beta\)) in Cell-1, that the distribution of air activity near working area, was wider compared to that near cell ventilation. This observation was in-line with the underlying physical process because:

-

a.

More variability in air activity near working area due to variety of activity generation processes like cutting, grinding etc.

-

b.

Dilution of air activity near cell ventilation point, owing to the dilution because of the cell volume.

Such an agreement between density estimates for air activity observations from two different sampling points validates the placement of sampling point near the high-APR generating operations.

Correlations between activity near working area and near cell ventilation varied with process cells

The correlation between alpha activity for CAM-NWA and alpha activity for CAM-NCV was strong for Cell-3 (= 0.86), whereas in Cell-1, the correlation between beta activity CAM-NWA and CAM-NCV was strong (= 0.84). This is another validation of the choice of our sampling point, considering that this observation was in line with the alpha and beta inventories which were handled in the respective process cells.

Practical application of the validation methodology

In scenarios where maintenance or repair activities are expected to generate APR, the methodology presented in this study offers a practical approach to validate the positioning of air monitors. Most task-related monitoring scenarios are likely to be of short duration. In such cases, it may not be feasible to conduct multiple tests to optimize the placement of special Continuous Air Monitors (CAMs).

We recommend a straightforward approach: position one CAM near the working area, where the APR is anticipated to be generated. This is the CAM whose location we intend to validate (i.e., if it faithfully captures the APR generation). This location is typically close to the source of APR generation (e.g., by cutting or welding a radioactive pipeline). The second CAM should be placed near the final ventilation duct of the containment area. In nuclear facilities, these areas are usually maintained under negative pressure to control APR concentration, ensuring that any airborne contaminants are directed towards the ventilation system.

If a permanent ventilation system is not in place, an ad hoc ventilation arrangement is typically introduced during APR-generating activities. In such instances, the second CAM, equivalent to the CAM-NCV in our study, should be positioned near the ventilation outlet. This placement ensures that the CAM captures the residual APR levels as the air exist the containment area.

The effectiveness of this validation methodology lies in the comparison of the probability distributions of APR concentrations recorded by the two CAMs, and by looking at correlations of activities as delineated in our work. By analyzing the kernel density estimates of the activity readings from both the CAM near the APR-generating area and the CAM near the ventilation duct, it is possible to assess whether the positioning of the CAM near the working area is optimal for detecting APR generated. This method ensures that the CAM near the working area is strategically placed to provide the most reliable data for protecting workers and maintaining safe operating conditions during high-APR generating operations.

Conclusions

The methodology presented in this paper provides a practical and robust approach for validating the positioning of Continuous Air Monitors (CAMs) in task-related air monitoring scenarios, particularly in environments with the potential for sudden rises in airborne particulate radioactivity (APR). In scenarios with short-duration monitoring, where it may not be feasible to test multiple sampling points, our method demonstrates that analyzing probability density functions and correlations of air activity between two strategically placed CAMs can effectively validate the location of the CAM near the working area. This is achieved by positioning one CAM close to the APR-generating source and another near the ventilation duct of the containment area. The method relies on comparing kernel density estimates of APR concentrations to assess the reliability of the CAM placement, independent of the exact radioactivity levels within the process cells. This approach is particularly valuable during high-APR generating operations, such as major repairs or decommissioning activities, where internal exposure control is of critical importance. By ensuring that the CAM near the working area is optimally placed, the methodology enhances the effectiveness of respiratory protection and overall worker safety. The application of this validation process does not depend on the exact levels of radioactivity being measured; however, care should be taken that the percentage of readings below the Minimum Detectable Activity (MDA) does not exceed 60% to avoid potential inaccuracies in statistical parameter estimation (i.e., the air activity dataset should not be heavily censored). It is unlikely that the air activity measurement data during high-APR generating will be censored. In our case study, only about 10% of the readings were below MDA. This methodology fills a gap in task-related air monitoring by providing a validated, efficient means of ensuring accurate air activity measurements, ultimately supporting the safe execution of tasks in radiation environments.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

U.S. Department of Energy. At COP28, countries launch declaration to triple nuclear energy capacity by 2050, recognizing the key role of nuclear energy in reaching net zero (2023). https://www.energy.gov/articles/cop28-countries-launch-declaration-triple-nuclear-energy-capacity-2050-recognizing-key. Accessed 11 April 2024.

OECD. Comparing nuclear accident risks with those from other energy sources (OECD Publishing, 2010). https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/9789264097995-en

United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation. Sources, effects and risks of ionizing radiation, UNSCEAR 2020/2021 report, Volume IV: Annex D–evaluation of occupational exposure to ionizing radiation. Technical report, United Nations, New York. https://www.unscear.org/unscear/en/publications/2020_2021.html (2022).

Kumar, A. V. et al. Negligible radiological impact of Indian nuclear power plants on the environment and the public: Findings from a 20-year study. Sci. Total Environ. 914, 169936 (2024).

Cramer, C., Lacivita, B., Laws, J., Malik, M. N. & Olynyk, G. What will it take for nuclear power to meet the climate challenge? (McKinsey & Company, 2023). https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/electric-power-and-natural-gas/our-insights/what-will-it-take-for-nuclear-power-to-meet-the-climate-challenge. Accessed 09 April 2024.

United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation. Sources and effects of ionizing radiation. UNSCEAR 2000 report to the general assembly, with scientific annexes. Volume I: Sources. Report, United Nations, Annex E–occupational radiation exposures. https://www.unscear.org/unscear/en/publications/2000_1.html (2000).

ISO 16639:2017. Surveillance of the activity concentrations of airborne radioactive substances in the workplace of nuclear facilities 1st edn. https://www.iso.org/standard/57345.html (2017).

Chakraborty, A. et al. Trend analysis of long-lived airborne contamination in a reprocessing facility. Radiat. Prot. Environ. 46, S63–S64 (2023).

Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Assigned protection factors for the revised respiratory protection standard. Technical report (U.S. Department of Labor, Washington, D.C., 2009).

Natarajan, R. Reprocessing of spent nuclear fuel in India: Present challenges and future programme. Prog. Nuclear Energy 101, 118–132 (2017).

International Atomic Energy Agency. Design and operation of evaporators for radioactive wastes. Technical report (International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Vienna, Austria, 1968).

Occupational Radiation Protection. No. GSG-7 in general safety guides (International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, 2018). https://www.iaea.org/publications/11113/occupational-radiation-protection

Hadlock, D. J. Use of DAC-hours for radiation work permit suspension guides and validation of respiratory equipment selection at the savannah river site. https://www.osti.gov/biblio/817233 (2003).

Parzen, E. On estimation of a probability density function and mode. Ann. Math. Stat. 33, 1065–1076 (1962).

Chen, Y.-C. A tutorial on kernel density estimation and recent advances. Biostat. Epidemiol. 1, 161–187 (2017).

Sheskin, D. J. Handbook of parametric and nonparametric statistical procedures 3rd edn. (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2003). https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420036268.

Waskom, M. L. Seaborn: Statistical data visualization. J. Open Source Softw. 6, 3021. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.03021 (2021).

Silverman, B. W. Density estimation for statistics and data analysis 1st edn. (Routledge, New York, 1998). https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315140919.

Schober, P., Boer, C. & Schwarte, L. A. Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 126, 1763–1768 (2018).

Funding

No funding was received for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.C.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing. N.P.: Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing. D.K.P.: Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing. P.K.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing. U.V. D.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing. J.P.N. P.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chakraborty, A., Parashar, N., Pandey, D.K. et al. Validation of sampling points for airborne radioactivity in particulate-generating operations. Sci Rep 14, 27120 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74788-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74788-5