Abstract

In order to tackle the issue of excessive coal dust and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) concurrently in underground coal mines, an alkaline dust suppressant was formulated by combining surfactant sodium sec-alkyl sulfonate (SAS60) and sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) at a certain mass ratio, meant for injection into coal seams. This study principally targeted long-flame coal extracted from Hequ County, located in Shanxi Province, China. The objective was to investigate and analyze the underlying process of how alkaline dust suppressants affect the wettability of coal. A comprehensive strategy including contact angle determination, Fourier transform infrared absorption spectrometer(FTIR) analysis, low-temperature nitrogen adsorption tests, scanning electron microscope(SEM) experimental studies, and molecular dynamics simulations was employed for this examination. The results revealed that merging Na2CO3 with SAS60 could reduce the coal’s contact angle. Despite the core structure of the coal surface staying unchanged after alkaline dust suppressant treatment, a rise in the number of hydrophilic functional groups was observed. This count notably surpassed the amount of hydrophobic functional groups, consequently boosting the coal’s hydrophilicity. The permeability of the examined coal specimens was chiefly affected by the existence of macropores and mesopores. Processing with 0.05 wt% SAS60 and 1.0 wt% Na2CO3, the coal acquired additional pores and cracks, causing an upswing of average pore size by 25.79% and a 30.64% increase in the maximum gas adsorption. This facilitated more straightforward infiltration of water into the coal dust. Molecular dynamics simulation outcomes indicated a closer affiliation between coal and water following the incorporation of Na2CO3. It led to a heightened activity in water molecule movement, fortifying intermolecular electrostatic interactions, and fostering the creation of hydrogen bonds. Consequently, this improved the coal’s wettability. The increase in the mass fraction of Na2CO3 directly corresponds to a more considerable enhancement in the solution’s ability to wet the coal. The outcomes of the molecular dynamics simulation validated the experimental results’ precision.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The depth and breadth of coal mines will continue to expand as global coal use continues to grow to meet the demands of global economic growth1,2,3. Both coal dust and H2S are occupational hazards that accompany coal mine production4,5. Coal dust is known to cause pneumoconiosis in workers, and the high concentration of coal dust also causes hazards such as spontaneous combustion and explosion6. H2S in coal seams is highly toxic, flammable, and explosive, and it is difficult to find the law of its existence because of its high activity and unstable form, which makes it difficult to prevent and control7. At present, the injection of water into coal seams is a prevalent method for managing coal dust, and the incorporation of surfactants into the solution can enhance the coal seam’s moisture absorption capability3,8,9,10. As for the treatment of H2S, catalytic desulphurization technology is mainly used in the USA and Australia, while Chinese coal mines tend to inject lye into the coal seam to remove H2S11. While these technologies exhibit some effectiveness in addressing a single issue, they fall short in concurrently lowering the levels of coal dust and H2S in subterranean coal mines12,13,14. Therefore, it is imperative to research new comprehensive reagents.

Li et al. determined that anionic/cationic surfactant blends significantly improved the wettability of low-rank coals through wettability experiments and molecular simulation studies15. Nie et al. and his team conducted a molecular simulation study to examine the wetting impact and mechanism of various surfactants on coal dust16. Wang et al. found that adding sodium dodecyl sulfate(SDS) could improve the proportions of oxygenated functional groups and strengthen the pore connectivity of the coal, which regulates its wettability and ability to absorb methane17.Niu et al. conducted research illustrating that alkyl polyglucoside-12(APG-12) could amplify the number of hydrophobic groups in coal and enhance the wetting impact, as validated via molecular dynamics simulations and experimental trials18. Gao et al. determined that through altering the surface electrical properties and energy of coal dust, surfactants can enhance the coal’s wettability1. Wang et al. discovered that incorporating inorganic salts into surfactants through wettability and water retention experiments could enhance the solution’s ability to wet coal19. Xia et al. discovered that the contact angle formed by coal samples immersed in an alkaline solution substantially diminished, suggesting that injecting such a solution into coal seams could potentially mitigate dust emission20. Tan et al. deduced that the variation in pH levels of solutions could modify the coal surface’s roughness, thereby influencing the effectiveness of water injection into coal seams21. Gao et al. studied the storage pattern of hydrogen sulfide in coal to guide management22. Usto et al. used sodium hydroxide to treat coking coal and achieved a final total desulfurization rate of more than 82%23. Zhang et al. found that adding surfactants to the lye solution could improve the removability of hydrogen sulfide24. In addition, the previous study formulated an alkaline dust suppressant by compounding surfactant and alkaline liquid, to simultaneously treat coal dust and hydrogen sulfide by coal seam solution injection, and the results showed that it could effectively promote the solution to wet the coal body as well as absorb hydrogen sulfide.

Prior research has concentrated on the process of coal wetting by neutral or acidic dust suppressants, yet the impact of alkaline solution on coal’s microstructure and wettability hasn’t been thoroughly examined. The reason why neutral inorganic salts promote the wettability of solution is that sodium ions improve the arrangement of surfactant molecules on the surface of solution through ion exchange, which belongs to physical change. However, there is relatively little research on the influence of acidic solution on coal wettability, mainly focusing on acidic fracturing fluid. The existing research shows that acid solution can react with carbonate in coal due to its acidic chemical properties, which leads to the change of physical and chemical properties of coal, which belongs to chemical changes, but acid is corrosive and will affect the properties of coal itself.

The effects of alkaline dust suppressants on coal are multifaceted due to their unique chemical properties, and it is necessary to study in depth its influence mechanism on coal wettability. Hence, SAS60 and Na2CO3 were compounded and formulated into an alkaline dust suppressant. The goal of this research is to unravel the microscale wetting process of coal dust by employing both experimental approaches and molecular dynamics simulation techniques. It is intended to assist coal mines in minimizing coal dust production, thereby ensuring safe operations. The alkaline dust suppressant suggested in this paper, designed to concurrently deal with coal dust and H2S in coal mines, is predicted to have significant practical application value.

Experiment

Materials for experiment

Gathering and processing of coal specimens

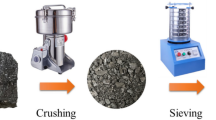

Figure 1 depicts that the coal specimens utilized in this study were long-flame coals procured from the 13# seam of Shaping coal mine situated in Hequ County, China. These samples were subjected to crushing and sieving to attain a fine dust with particle size below 0.075 mm, followed by vacuum drying at 80 ℃ for a duration of 10 h. Subsequently, they were tightly sealed and conserved under conditions of low temperature and protection from light.

Through the determination of maceral in coal, the maceral of this coal sample is mainly vitrinite and inertinite, and a small amount is crustaceous. The content of vitrinite and hemivitrinite is between 5.76% and 75.4%, with an average of 35.44%. The content of inert and semi-inert components is between 14.70% and 75.59%, with an average of 42.13%. The content of chitin is between 3.30% and 16.94%, with an average of 9.05%. Coal surface contains some inorganic components (minerals), mainly clay minerals, with a small amount of sulfide and carbonate.

Contact angle experiment

The coal dust was taken and pressed into coal flakes 20 mm in diameter and 5 mm thick using a flake press for 5 min at a pressure of 30 MPa. The contact angles between various concentration solutions and coal pieces were gauged using the JC2000D2M contact angle measuring device from Shanghai, China. Each sample underwent at least three evaluations, and the outcomes were averaged to guarantee the dependability of the experimental figures.

FTIR test

Prior to experimentation, coal specimens were combined with KBr in a 1:200 proportion and intensively pulverized in an agate grinding bowl. Subsequently, the blended material was shaped into slender slices and subjected to vacuum drying at 60 °C for a duration of 6 h to avert any water influence on the test outcomes. The assessments were performed using a FTIR spectrometer Nicolet6700, a product of Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA. Its precision is defined at 4 cm−1 and its comprehensive scanning duration is 32 cycles, with the spectral range from 400 cm−1 to 4000 cm−1.

Low-temperature nitrogen adsorption test

ASAP2020, a fully automated physical/chemical adsorption device made by Micromeritics (USA), was deployed for conducting low-temperature liquid nitrogen adsorption tests with nitrogen serving as the adsorbent. Following the cleansing and drying processes of the coal, it was subjected to degassing for about six hours at approximately 100 °C before assessing relevant characteristics such as isothermal adsorption-desorption.

SEM

Signals captured from reflected or secondary electrons permit scanning electron microscopy to depict images of coal surfaces after immersion in alkali dust suppressants. Before commencing the experiment, a gold-sputtering process is necessary as a preparatory step for the coal sample. Following this, the electron beam’s path is controlled to facilitate a comprehensive scan of the specimen.

Molecular dynamics simulation

Using the Forcite module of Materials Studio software of version 19.1, molecular dynamics simulations were carried out, enabling the investigation of relative concentration distribution, water molecules’ mean-square displacement, and interaction energies within the system. This illuminates the moistening process of coal when exposed to alkaline dust suppressants.

The coal molecules were substituted with the Wiser Bituminous Coal Molecular Model, a prevalent model that significantly conveys bituminous coal attributes25. Individual molecular models were optimized using Geometry Optimization and Anneal within the Forcite block, aiming to reduce the energy levels of each molecule and enhance the stability of the molecular structure. The ultimate molecular configurations achieved are exhibited in Fig. 2.

The periodic cell structures containing five coal molecules, 15 SAS60 molecules, and 1,000 water molecules were constructed at the bottom edge size of 35 Å × 35 Å by the Amorphous Cell command, and then optimized for each cell structure, respectively. A three-dimensional rectangular simulation framework was established using the ‘Build layers’ command, imposing periodic boundary conditions. A vacuum layer of 100 Å was constructed above it to minimize the effects from the periodic boundary. Using a comparable approach, systems comprising 51 and 153 Na2CO3 molecules were assembled, symbolizing Na2CO3 concentrations of 0.1 wt% and 0.3 wt%, respectively. The construction of each system is shown in Table 1.

After each system was optimized, Forcite’s Dynamics module was employed for executing molecular dynamics simulations. Each molecule received its corresponding charge and the COMPASS II force field was selected due to its relevance to ionic liquids and its proficiency in promptly and accurately anticipating the structure, conformation, frequency, and thermophysical properties of the system26. The simulation was conducted with a time increment of 1.0 fs. To maintain a temperature of 298 K, the Nose method was engaged. The atomic method was used to calculate Van der Waals interactions, and molecular dynamics simulations extended over a span of 400 ps under the canonical ensemble NVT.

Findings and interpretation

FTIR analysis

Research indicates that the surface of coal is rich in various chemical functional groups. The existence and ratio of oxygen-containing functionalities significantly affect the wetness attribute of coal. At the same time, functionalities such as aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons are observed to have an adverse effect on coal’s wettability27.

Figure 3 portrays the infrared spectra of coal specimens subjected to various reagent treatments. The results showed that the positions of the wave peaks were approximately unchanged between the original coal and the treated coal, and the overall trends of the infrared spectra were roughly the same, indicating that the fundamental structure of the coal functional groups did not change.

The infrared spectrum was categorized into four sections, considering the hydrophobic and hydrophilic properties of the functional groups3. Region A (3600 ~ 3200 cm−1) belongs to the hydrophilic functional group region, which was mainly the region of the hydroxyl group’s stretching vibration. Region B (3000 ~ 2850 cm−1) and D (900 ~ 750 cm−1) belong to the hydrophobic functional group region, mainly containing aliphatic structures and aromatic groups, etc. Region C, ranging from 1800 –1000 cm−1, encompasses numerous hydrophilic functional groups along with certain hydrophobic functional groups28. For coal samples subjected to different treatments, their respective infrared spectra peaks were individually identified and fitted via Peakfit software version 4.0. This was done to deduce the area size of the wave peaks in each functional group region and calculate their corresponding percentage. Figure 4 exhibits the split-peak fitting spectra of coal specimens processed with 0.05 wt% SAS60 and 1.0 wt% Na2CO3.

Table 2 shows the spread and proportion of functional groups in every section of the coal specimens pre and post processing. When compared with the unprocessed coal, there is a noticeable surge in the makeup of functional groups in the treated coal, specifically the water-attracting, oxygen-bearing functional groups.

As depicted in Fig. 4; Table 2, a significant increase in the peak area of region A in the infrared spectra was observed for coal specimens processed with alkaline dust suppressant compared to unprocessed coal. The key supporting data for this is the augmented appearance of hydroxyl self-consolidated hydrogen bonds (OH-OH) close to 3398.24 cm−1, coupled with a surge in the number of hydroxyl π-hydrogen bonds (OH-π) and hydroxyl ether hydrogen bonds (OH-O) around 3473.38 cm−1. The analysis indicated that the reduced surface tension of the alkaline dust suppressant encouraged more water to engage with the coal. This led to an increase in free hydroxyl groups, subsequently fostering hydrogen bond formation. Moreover, the peak area in region C was also greatly enhanced, which was mainly manifested by the appearance of super-intense peaks at 1010.57 ~ 1033.65 cm−1 for the C-O stretching vibration of alkyl ether and C-O-C symmetric stretching vibration of aryl ethers near 1105.01 cm−1, and it could be attributed to the alkaline solution prompting the generation of ether bonds.

The peak areas in regions B and D, primarily representative of hydrophobic functional groups, saw minimal enhancement. The primary display of this was the off-balance stretching oscillation of -CH2 around 2921.73 cm−1 in zone B and benzene ring’s tri-substitution approximately at 792.64 cm−1in zone D. This analysis was seen as the outcome of the chemical interplay between the substances on the coal surface and the alkali-based dust suppressant. Although there is a minor increase in hydrophobic functional groups, the proliferation of more oxygen-containing functional groups could amplify the hydrophilic quality of the coal surface. This allowed for easier water distribution when in contact with the coal surface, consequently reducing the contact angle29. The findings suggest that the inclusion of Na2CO3 in the surfactant can further enhance the solution’s ability to moisten the coal.

Contact angle analysis

The contact angle serves as a vital measure of wettability30. A decrease in contact angle corresponds to an enhancement in the wetting behavior of the liquid on the solid substrate31. As inferred from Eq. (1), lowering the liquid’s surface tension decreases the surface energy required for the liquid to scatter on the solid surface. Simultaneously, the difference between the surface energies of solid-gas and solid-liquid increases, leading to a smaller contact angle32.

In this context, γsg denotes the interfacial tension between solid and gas, measured in N/m; γsl symbolizes the surface tension occurring between solid and liquid, also in units of N/m; γlg refers to the interfacial tension between liquid and gas, given in N/m; while θ signifies the angle of contact at the solid-liquid interface, expressed in degrees (°).

Given that prior research indicated the optimal concentration of SAS60 solution to be 0.05 wt%, this amount was utilized to create an alkaline dust suppressant with eight distinct concentrations (0.05 wt%, 0.1 wt%, 0.3 wt%, 0.5 wt%, 0.7 wt%, 1.0 wt%, 1.5 wt%, and 2.0 wt%) of Na2CO3. This was done in order to determine the contact angle with the coal flakes correspondingly. Figure 5 illustrates the trend of alterations in the contact angle between alkaline dust suppressants, containing varying concentrations of Na2CO3, and coal fragments. This signifies that the introduction of Na2CO3 can further reduce the contact angle between the suppressant and coal fragments, particularly when SAS60 is utilized at its optimal mass fraction. When the concentration of Na2CO3 attained 1.0 wt%, the shift in the contact angle almost halted. At this point, in relation to the isolated SAS60 monomer, the interaction angle between the agent and coal fragments had decreased by 44.84%. This indicates that the addition of Na2CO3 to the SAS60 mixture can amplify its moisture absorption properties. This has been found to be profoundly connected with the functional groups on the coal surface, as well as the structure of the coal’s pores.

Analysis of pore structure

Investigation of specific surface region and pore capacity attributes

The coal surface possesses a diverse range of pore formations and incorporates multiple mineral elements33. Evidence has shown that the configuration of coal’s pore structure can have a substantial influence on its wettability34. To meticulously analyze the effect mechanism of alkaline dust suppressants on coal, the pore structure of several coal specimens was evaluated via scientific experiments.

Several theoretical models of adsorption have been suggested by earlier researchers. Due to its exceptional accuracy in quantifying the complete range of pore sizes, which stems from the density-functional theory, the density functional theory(DFT) model was employed to determine the pore volume in the coal specimens. The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller(BET) equation, widely acknowledged for its accuracy in calculating specific surface area, can be computed using the subsequent equations:

In the above equations, Qm is the adsorbed amount when the monomolecular layer is saturated, measured in cm3/g; Q is the amount of gas adsorbed at different relative pressures, also in cm3/g; S stands for the specific surface area, measured in m2/g; P0 indicates the saturation vapor pressure, given in MPa; and C is a coefficient corresponding to the liquefaction heat of the adsorbent. In addition, am signifies the cross-sectional area, expressed in nm2; and NA is Avogadro’s constant, denoted as 6.02 × 1023. Moreover, the categorization of the pore dimensions in the coal samples was performed adhering to International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry(IUPAC)standards, The pore size of micropores is less than 2 nm, the pore size of mesopores is between 2 and 50 nm, and those larger than 50 nm are macropores.The associated figures are presented in Table 3.

After evaluating the table data, a minor reduction of 1.84% in the exposed area of coal specimens processed with SAS60 was observed compared to the original coal. Conversely, the overall pore capacity saw an increment of 3.3%, signifying a reduction in micropore content and an enhancement in mesopore content due to the influence of SAS60. This likely occurred due to the dissolution of some kaolinite minerals surrounding the mesopores by water leaching. This situation caused an increase in the diameter of mesopores and macropores, while the collapsed minerals obstructed the entrances to the micropores35.

When compared to the initial coal, the coal samples infused with SAS60 and a substantial quantity of Na2CO3 experienced an increase of 8.11% in their particular area of surface. The enhancement in the pore volume was recorded as 25.67%, 19.75%, and 28.85% for micro, meso, and macroporous pores, respectively. Additionally, there was a significant increase of 25.79% in the mean pore dimension. The mineral composition of coal has been tested in 2.1.1. Considering that the inorganic components in coal are mainly clay minerals, this could be linked to the occurrence wherein inorganic minerals like clay, feldspar, or quartz surrounding the mesopores dissolved due to reactions with trace amounts of Na2CO3 in the solution. This process resulted in the creation of a vast number of secondary pores and subsequently led to the enlargement of mesopore dimensions.

Isothermal adsorption and desorption curves

The distribution of pores and the fundamental morphological characteristics in coal could be preliminarily estimated by analyzing the isothermal adsorption and desorption curves36. According to the IUPAC-standardized classification of adsorption isotherms, the adsorption and desorption plots for the experimental coal samples corresponded with the characteristics of IV(a) type isotherm. This implies that monomolecular layer adsorption occurred during ultra-low pressure phases, while multimolecular layer adsorption emerged as the relative pressure escalated. Around a relative pressure (P/P0) of approximately 0.5, capillary condensation took place and there was a swift increase in adsorption. As P/P0 neared 1, no adsorption plateau was observed and the adsorption did not reach saturation, implying the presence of a certain count of macropores in the coal. The adsorption and desorption curves of each coal sample are shown in Fig. 6.

The absorption and emission graphs of the coal samples displayed visible distinction pre and post treatment. A conspicuous ‘hysteresis loop’ was observed in the desorption segment when the P/P0ratio was approximately 0.5. Per the standard categorization of hysteresis loops by IUPAC, all coal samples qualify as type H337. This suggests the presence of open and semi-open pores in the coal.

The analysis of the adsorption/desorption isotherms revealed a substantial surge in the adsorption volumes of the remaining three coal samples by 18.17%, 19.87%, and 30.64% respectively in comparison to the unprocessed coal at a P/P0 ratio of 1. The separation of the hysteresis return lines in Fig. 6(d) becomes larger, indicating that Na2CO3 can effectively improve pore connectivity and enlarge pore width to promote gas adsorption and desorption. Moreover, the coal comprised of slit-like and ink-bottle-like pores, a factor that enhanced its water holding capacity.

Traits of pore size variation

The Barrett-Joiner- Halenda(BJH) model was utilized for assessing pore size characteristics of the coal, specifically investigating pore diameters between 1.7 and 180 nm38. Figure 7 depicts the characteristics of coal’s pore size prior to and following immersion in SAS60 and alkaline dust suppressant. The coal’s pore size mainly showcased two interval peaks at 3 ~ 4 nm and 20 ~ 100 nm. This can be attributed to the long-flame coal samples used with a lower rank, having looser pores and well-explored cracks, comprising mostly intergranular pores and dominated by medium to large pores.

Both peak intervals displayed significantly higher peak values in coal samples treated with SAS60 and alkaline dust suppressant, suggesting an upsurge in the count of medium to large pores as well as a surge in overall pore volume. The solutions react mainly with the organic and inorganic substances on the coal surface and do not destroy the essential structure of coal39.

Figure 7b illustrates that with increasing pore size, the cumulative pore volume for all treated coal samples under various conditions exhibited a rise. The growth was sharp from 2 nm to 20 nm, moderate from 20 nm to 100 nm, and became stable beyond 100 nm. Each coal sample indicated minor changes in the cumulative pore volume in the micropore sphere and substantial changes in the larger and medium pore sphere. This suggests that medium to large pores significantly impact Shaping coal’s wettability.

The cumulative pore volume of the coal samples subjected to alkaline dust suppressant treatment exhibited the quickest increase rate in the 2 nm ~ 20 nm phase, and its peak value was notably greater than the other three. This suggests that the alkaline dust suppressant has a stronger influence on the coal, meaning the dissolution of minerals from the coal surface contributes to the creation of new pores. Meanwhile, the solution reacts with the minerals around the medium and large pores, enlarging the pores width and increasing the connectivity of the pores.In this way, water can pass through the pores to wet the coal body more completely.

SEM analysis

SEM pictures help describe the coal surface’s shape, the key characteristics of which back up the analysis in Sect. Analysis of pore structure. Figure 8presents SEM shots of coal samples post-treatment with different solutions, indicating that the original coal surface was fairly level, barring a few apertures and mineral particles sticking to the coal surface. Due to the dissolving of water-absorbent minerals like montmorillonite and kaolinite, the SAS60 treated coal surface displayed signs of water penetration, more broken pores, and a somewhat enlarged total pore volume. Minerals surrounding the micropores that have absorbed water swelled, leading to pore blockage and a slight decrease in the specific surface area40.

The exterior of the coal subjected to SAS60 and 0.1 wt% Na2CO3 started to show dissolution cavities and small cracks, but these features became more evident in the specimens when the mass fraction of Na2CO3was raised to 1.0%. The increase in the number of dissolved pores, along with the expansion of the pore diameter, contributes to the enhancement in porosity. The exterior of the coal showcases prominent cracks and compound groupings, primarily arising from the erosive dissolution of hard minerals such as quartz and feldspar in clay, especially in alkaline circumstances41.

These phenomena suggested that the alkaline dust suppressant could lead to an increase in coal pore size as well as the appearance of cracks, thus enhancing inter-pore connectivity. Water has the potential to moisten the coal structure thoroughly, thereby increasing its permeability. This can result in enhanced coal wettability and a reduction in dust production during the grinding and coal-drop stages of underground coal extraction.

Examination of outcomes from molecular dynamics simulation

Figure 9 illustrates the status of each system following 400 ps under the ‘Dynamics’ command in the Forcite module. The findings indicate that driven by the surfactant SAS60 and Na2CO3, water molecules gravitate towards and permeate into coal molecules, thereby moistening the coal framework. However, the degree of movement and the capability of water molecules to infiltrate vary among systems with disparate concentrations of Na2CO3. The relative concentration distributions, mean square displacements, and interaction energy amongst water molecules, SAS60 molecules, and coal molecules as well as Na2CO3 were analyzed to clarify the mechanism.

Distribution of proportional concentration

The relative concentration distribution of a molecule or group indicates its positional distribution in a direction in the system, and its peak means the intensity of aggregation at that point42. The relative concentration distributions of three different liquids, water, SAS60 and the SAS60/Na2CO3 composite system were analyzed by the Foecite module and shown in Fig. 10.

The dispersion of relative coal concentrations shows minor fluctuations, mainly ranging between 18 Å to 68 Å. In contrast to System 1, the remaining systems present a wider cross-section of water and coal molecule trajectories, suggesting that additional water associates with the coal surface through a middle agent.

The adsorbed layer’s thickness on the coal surface expanded from 2 Å to 11 Å upon the addition of SAS60 as a go-between for the coal and water molecules. With 51 Na2CO3 molecules in the intermediary medium layer, the intersection area of water and coal molecule curves was 5.7505. However, when the quantity of Na2CO3 escalated to 153, the said area also expanded to 7.3079. This outcome suggests that the incorporation of Na2CO3 into the surfactant further boosts the coal-wetting capacity of the solution. Moreover, this wetting effect amplifies as the concentration of Na2CO3 rises.

Mean square displacement of water molecules

The Mean Square Displacement (MSD) can serve as an indicator of a particle’s capacity to diffuse43. The impact of Na2CO3and SAS60 molecules on the trajectory of water molecules can be elucidated more effectively by further calculations of water molecules’ MSD and the ‘D’ diffusion coefficient. The formulae for calculating MSD and the diffusion coefficient are presented below44:

In this context, KMSD denotes the slope of the adjusted curve; N stands for the total number of diffusing molecules; while r(t) and r(0) represent the position vectors of water molecules at any given time t and at the commencement time (t = 0) respectively.

During the initial 300 ps of the simulation, the molecules were more steady, hence the data from this segment was charted and adjusted, as demonstrated in Fig. 11.

As water molecules are inclined to migrate towards coal, their vigorous movement makes them more susceptible to absorption by coal. This suggests that the quicker the dispersion of water molecules on the coal surface, the more intensified the coal-wetting effect is. Figure 11 illustrates an increased steepness in the curve of MSD of water molecules when Na2CO3 is present, suggesting a heightened intensity of water molecular motion with the addition of SAS60 and Na2CO3 to the mixtures.

The primary factor is that Na2CO3alkalizes the solution, leading to an increased deprotonation level of hydrophilic groups. This reduces the electrostatic repulsion between molecules, encouraging hydrogen bond formation between active groups and water molecules, thereby enhancing the wetting efficiency45. This enhancing effect was more noticeable at elevated concentrations of Na2CO3, suggesting that augmenting the amount of Na2CO3 can somewhat boost the wetting impact of the alkaline dust suppressant.

Interaction energy

The variation in the interaction energy of the system leads to changes in how well the solution wets the coal. To evaluate the wetting effect of different solutions on coal, the interaction energy for each system was computed, and its calculation formula is as follows43,

The notation used is as follows: Eint symbolizes the interactive power of the system, indicated in kcal/mol; Et encapsulates the entire system’s energy, also expressed in kcal/mol; Ec, Ew, and Es represent the energies associated with coal, water, and the dielectric layer, each calculated in kcal /mol, by independently subtracting the other two elements from the system. Table 4 illustrates the calculated Eint and Enon of various systems by the Forcite module.

When Eint < 0, the adsorption effect in the systems occurs spontaneously. Clearly, S4’s Eint possesses the highest absolute value, suggesting the most vigorous molecular interactions and the peak coal wettability within this system. The observation that Eele is larger than Evan in all systems implies that the alterations in wetting effects are primarily attributed to electrostatic interactions. Meanwhile, the increase in hydrogen bonding is precisely due to the enhancement of electrostatic interactions, which explains the more vigorous movement of the water molecules in Sect. 3.5.3 further.

Conclusion

In this paper, SAS60 and Na2CO3 were mixed at some ratio to formulate an alkaline dust suppressant, and its microscopic wetting mechanism on coal was investigated, with the following conclusions:

(1) Infusing Na2CO3 into SAS60 could lessen the interaction angle between the blends and coal. The proportion of water-attracting functional groups notably outpaced that of water-repelling ones, thus amplifying the water-absorbing property of the coal surface. In addition, the effect heightens when the weight% of Na2CO3 increases. Likewise, the impact becomes even more apparent with further rise in the mass fraction of Na2CO3.

(2) Investigations using low-temperature liquid nitrogen adsorption and SEM demonstrated that macropores and mesopores primarily influence the coal’s wetness characteristics. The coal soaked in the solution containing 0.05 wt% SAS60 and 1.0 wt% Na2CO3 showed an increase of 25.79% in the average pore size and 30.64% in the maximum gas adsorption, which encouraged the water to infiltrate the coal dust more easily.

(3) The findings from the molecular dynamics simulation implied that Na2CO3 strengthens the adsorptive interaction between coal and water molecules. This in turn escalates the motility of water molecules and assists in the formation of hydrogen bonds. In addition, it strengthens the intermolecular electrostatic interactions, resulting in higher interaction energy and better wettability. The simulation results verified the accuracy of the experiments.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Gao, M. Z. et al. Mechanism of micro-wetting of highly hydrophobic coal dust in underground mining and new wetting agent development. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 33 (1), 31–46 (2023).

Sun, J., Zhou, G., Wang, C. M., Liu, R. L. & Miao, Y. N. Experimental synthesis and performance comparison analysis of high-efficiency wetting enhancers for coal seam water injection. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 147, 320–333 (2021).

Shi, G. Q., Han, C., Wang, Y. M. & Wang, H. T. Experimental study on synergistic wetting of a coal dust with dust suppressant compounded with noncationic surfactants and its mechanism analysis. Powder Technol. 356, 1077–1086 (2019).

Qin, X., Cai, J. & Wang, G. Pore-scale modeling of pore structure properties and wettability effect on permeability of low-rank coal. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 33(5), 573–584 (2023).

Han, W. B. et al. Experimental investigation on combined modification for micro physicochemical characteristics of coal by compound reagents and liquid nitrogen freeze-thaw cycle. Fuel. 292, 120287 (2021).

Zazouli, M. A. et al. Physico-chemical properties and reactive oxygen species generation by respirable coal dust: implication for human health risk assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 405, 124185 (2021).

Zhang, C. et al. Controls on hydrogen sulfide formation and techniques for its treatment in the Binchang Xiaozhuang Coal Mine, China. Energy Fuels. 33(1), 266–275 (2018).

Li, B., Liu, S. & Fan, M. The effect of ethylene oxide groups in dodecyl ethoxyl ethers on low rank coal flotation: an experimental study and simulation. Powder Technol. 344, 684–692 (2019).

Wang, X. N., Yuan, S. J. & Jiang, B. Y. Experimental investigation of the wetting ability of surfactants to coals dust based on physical chemistry characteristics of the different coal samples. Adv. Powder Technol. 30(8), 1696–1708 (2019).

Li, J. L., Zhou, F. B. & Liu, H. The selection and application of a compound wetting agent to the coal seam water infusion for dust control. Int. J. Coal Preparation Utilization. 36(4), 192–206 (2016).

Zang, C. et al. Optimization of the ratio of modified alkaline solution for hydrogen sulfide treatment in coal mine based on response surface method. J. China Coal Soc. 45(8), 2926–2932 (2020). (in Chinese).

Sönmez, Ö., Yıldız, Ö., Çakır, M. Ö., Gozmen, B. & Giray, E. S. Influence of the addition of various ionic liquids on coal extraction with NMP. Fuel. 212, 12–18 (2018).

Kelebek, S. et al. The effects of dodecylamine, kerosene and pH on batch flotation of Turkey’s Tuncbilek coal. Int. J. Miner. Process. 88 (3–4), 65–71 (2008).

Zhou, Q., Qin, B. T., Wang, J., Wang, H. T. & Wang, F. Experimental investigation on the changes of the wettability and surface characteristics of coal dust with different fractal dimensions. Colloids Surf., a. 551, 148–157 (2018).

Li, W. F. et al. Effect of mixed cationic/anionic surfactants on the low-rank coal wettability by an experimental and molecular dynamics simulation. Fuel. 289, 119886 (2021).

Nie, W., Niu, W. J., Bao, Q., Yu, F. N. & Tian, Q. F. Effect of different surfactants on the wettability of coal dust based on Dmol3 module. J. China Coal Soc. 48(03), 1255–1266 (2023). (in Chinese).

Wang, Y. H. et al. Effect of SDS modified coal microstructure on wettability and methane adsorption. Fuel. 337, 127174 (2023).

Niu, W. J. et al. Study of the microscopic mechanism of lauryl glucoside wetting coal dust: environmental pollution prevention and contro. J. Hazard. Mater. 412, 125223 (2021).

Wang, P. F., Jiang, Y. D., Liu, R. H., Liu, L. M. & He, Y. C. Experimental study on the improvement of wetting performance of OP-10 solution by inorganic salt additives. Atmospheric Pollution Res. 11 (6), 153–161 (2020).

Xia, D. P. et al. Experimental study on reducing outburst proneness of coal seam via alkaline solution. J. China Coal Soc. 40(8), 1768–1773 (2015). (in Chinese).

Tan, J. Q., Hu, C. E., Lyu, Q., Feng, G. & Chen, S. F. Experimental investigation on the effects of different fracturing fluids on shale surface morphology. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 212, 110356 (2022).

Gao, F. et al. Study on H2S occurrence in low Sulfur coal seams. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 40 (1), 193–205 (2021).

Usto, M. A. et al. Desulfurization of thar lignite by oxidative alkali leaching under pressure. Int. J. Coal Preparation Utilization. 42(11), 3430–3450 (2022).

Zhang, C. et al. Development and application of modified lye for treating hydrogen sulphide in coal mine. Fuel. 269, 117233 (2020).

Zhou, G. et al. Study on wetting behavior between CTAC and BS-12 with gas coal based on molecular dynamics simulation. J. Mol. Liq. 357, 118996 (2022).

Yuan, M. Y. et al. Determining the effect of the non-ionic surfactant AEO9 on lignite adsorption and wetting via molecular dynamics (MD) simulation and experiment comparisons. Fuel. 278, 118339 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Experimental study on the influence of acid fracturing fluid on coal wettability. Fuel. 343, 127965 (2023).

Xu, C. H. et al. Experimental investigation of coal dust wetting ability of anionic surfactants with different structures. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 121, 69–76 (2019).

Cheng, W. M., Xue, J., Zhou, G., Nie, W. & Wen, J. H. Research on the relationship between bituminous coal dust wettability and inorganic mineral content. Joural China Univ. Min. Technol. 45(03), 462–468 (2016). (in Chinese).

Zhou, G., Wang, Q., Li, S. L., Huang, Q. M. & Liu, Z. Effect of a newly synthesized anionic Gemini surfactant composite fracturing system on the wettability of coking coal. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 169, 13–23 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. Effect of active composite ionic liquids treatment on chemical structure and wettability of coal. Fuel. 337, 126885 (2023).

Ma, Y. L., Sun, J., Ding, J. F. & Liu, Z. Y. Synthesis and characterization of a penetrating and pre-wetting agent for coal seam water injection. Powder Technol. 380, 368–376 (2021).

Klaver, J., Desbois, G., Urai, J. L. & Littke, R. BIB-SEM study of the pore space morphology in early mature Posidonia Shale from the Hils area, Germany. Int. J. Coal Geol. 103, 12–25 (2012).

Zhang, L. et al. Molecular simulation of effect of pore structure on wettability of low-rank coal. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 51(06), 1117–1127 (2022). (in Chinese).

Ji, H. J., Cheng, W. Y., Hu, S. B., Li, J. N. & Chen, J. W. Effects of organic micromolecules in coal on its wettability. J. Dispersion Sci. Technol. 39(9), 1229–1235 (2018).

Muttakin, M. et al. Theoretical framework to evaluate minimum desorption temperature for IUPAC classified adsorption isotherms. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 122, 795–805 (2018).

Si, L. L. et al. The influence of long-time water intrusion on the mineral and pore structure of coal. Fuel. 290, 119848 (2021).

Si, L. L. et al. The influence of inorganic salt on coal-water wetting angle and its mechanism on eliminating water blocking effect. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 103, 104618 (2022).

Wei, J. P., Wang, H. Y., Si, L. L. & Xi, Y. J. Characteristics of coal-water solid-liquid contact in gas atmosphere. J. China Coal Soc. 47, 323–332 (2022). (in Chinese).

Weishauptova ´, Z., Pˇribyl, O., Sýkorova ´, I. & Machovic, V. Effect of bituminous coal properties on carbon dioxide and methane high pressure sorption. Fuel. 139, 115–124 (2015).

Yao, Y., Wei, M. Z. & Kang, W. L. A review of wettability alteration using surfactants in carbonate reservoirs. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 294, 102477 (2021).

Lyu, X. J. et al. Adsorption and molecular dynamics simulations of nonionic surfactant on the low rank coal surface. Fuel. 211, 529–534 (2018).

Guo, J. Y., Zhang, L., Liu, S. Y. & Li, B. Effects of hydrophilic groups of nonionic surfactants on the wettability of lignite surface: molecular dynamics simulation and experimental study. Fuel. 231, 449–457 (2018).

You, X. F. et al. Molecular dynamics simulations of nonylphenol ethoxylate on the Hatcher model of subbituminous coal surface. Powder Technol. 332, 323–330 (2018).

Lucassen-Reynders, E. H., Lucassen, J. & Giles, D. Surface and bulk properties of mixed anionic/cationic surfactant systems i. equilibrium surface tensions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 81(1), 150–157 (1981).

Acknowledgements

This work has been funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China ( No. 51604138) and the upper-level project of the Liaoning Provincial Natural Science Foundation Program (2022-MS-395).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.A. provided funds, reviewed the manuscript and proposed amendments. S.L.did experiments and simulations, analyzed the data, wrote the whole manuscript and revised it. S.Z. and X.M mainly provides experimental materials and field working conditions. Z.j. reviewed the manuscript and proposed amendments.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ai, C., Liu, S., Zhao, S. et al. An investigative and simulative study on the wetting mechanism of alkaline dust suppressant acting on long-flame coal. Sci Rep 14, 26794 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74843-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74843-1