Abstract

Previous studies have reported that bodily self-consciousness could be altered so that one’s body was perceived in extra-personal space. However, whether this could be induced without tactile stimuli has not been investigated. We investigated whether out-of-body illusion could be induced via synchronized audio-visual stimuli, in which auditory stimuli were used instead of tactile stimuli. We conducted an experiment in which a sounding bell was moved in front of the participant, and synchronously, a non-sounding bell was moved in front of a camera that captured the image and projected on a head-mounted device. We expected the participants to experience that the sound came from the non-sounding bell in the video and they were in the camera’s position. Results from the questionnaires conducted after the experiment revealed that items related to out-of-body illusion were significantly enhanced in the synchronized conditions. Furthermore, participants reported a similarly strong out-of-body illusion for both the synchronized audio-visual and tactile-visual stimuli. This study demonstrated that out-of-body illusion could also be induced by synchronized audio-visual stimuli, which was a novel finding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Virtual reality (VR), which allows users to experience virtual spaces as if they were real, has recently attracted attention. Self-projection, the reproduction of the features of a real space consistent among different modalities in a virtual space, is an important element in VR1,2,3. Another important element is the reproduction of these consistent sensory stimuli in a virtual space that makes one perceive their whole body as being in the virtual space. Previous studies on bodily self-consciousness in the field of cognitive neuroscience examined how one recognized their own body, which was sense of embodiment that referred to the sensations of being inside, having, and controlling a body4,5,6,7. Humans can experience the sensation of their entire body outside of their physical body via synchronous visual and tactile stimulation. However, how auditory stimulation affects this illusion of the sensation of the entire body remains unclear.

Previous studies on sense of embodiment utilized out-of-body illusion4,5,6,7, the illusion that one’s sense of embodiment was outside the real body. These out-of-body illusions bear some similarities to out-of-body experiences described in patients with neurological problems; particularly, the experience of one’s sense of self being located in a different place from the real body. Out-of-body illusions involve changes in certain aspects of the feeling of embodiment, namely self-location and body ownership. Sense of embodiment refers to the perception that one’s body is one’s own and the experience of having control over it in a specific location, which includes places different from one’s actual physical body. It encompasses three main components: (1) self-location: the feeling that one’s body or a part of it is located in a specific position in space, (2) agency: the sense that one is the cause of their own actions and movements, and (3) body ownership: the sense that one’s body or a part of it belongs to oneself. Sense of embodiment is a crucial aspect in how we interact with the world and our sense of self. It can be affected by various factors, such as neurological conditions, virtual reality experiences, and certain psychological disorders.

Out-of-body experiences can be induced by drug abuse, general anesthesia, and sleep8. Furthermore, a previous study revealed that they could be experimentally induced in healthy participants via VR technology9. This study primarily focused on the phenomenon of an out-of-body illusion being experimentally induced via a VR environment. Ehrsson stated that tactile-visual stimuli caused participants’ sense of embodiment to arise at the location of the camera positioned behind them. Participants observed their back in real time via a head-mounted device (HMD). Subsequently, the experimenter moved a stick in a poking motion toward the bottom of the camera, which was presented as a visual stimulus as it was visible in the video. Simultaneously, another stick poked the participant’s chest as a tactile stimulus. Hence, participants felt as if their chests were being poked as the stick moved toward the bottom of the camera, which corresponded to the location where the stick poked, as if their bodies were in the camera’s position. Importantly, this out-of-body illusion was induced when visual and somatosensory stimuli were synchronized; however, it was not induced when they were asynchronized. Furthermore, Guterstam and Ehrsson conducted a follow-up experiment that involved an out-of-body illusion via both synchronous and asynchronous conditions10. In addition, Petkova and Ehrsson reported a version of an out-of-body illusion induced by synchronous finger movements in a “hand-shaking task”11.

Somatic sensation and proprioception, the sensations of recognizing the positions of one’s joints through movement, are part of somatic sensations1. Integrating information from somatic and visual sensation processing influences sense of embodiment4,12,13,14,15,16. Tactile stimuli are directly inputted to the skin as somatosensory stimuli and could affect sense of embodiment via the somatosensory system, which passes through the actual physical body. However, studies have not examined whether out-of-body illusions could be induced without somatic sensations related to tactile stimulation.

A previous study suggested that audio-visual stimuli affected sense of ownership, a part of sense of embodiment, in a mannequin’s ear17. A microphone was inserted into the left ear of a mannequin-like dummy head and played the sound of a brush tickling that ear. The participant’s actual ear felt ticklish when this sound was presented via headphones close to their actual ear, even though the ear of the actual body was not being physically tickled. This suggested that simultaneous and synchronized audio-visual stimuli elicited an illusion of sense of embodiment in the mannequin’s ears. Other studies reported that when one made a sound when they tapped the floor, which seemed to come from a distance, one felt as if their arms were longer than they were. This suggested that hearing could affect the recognition of one’s body2. Lesur et al.18 investigated the induction of audio-induced autoscopy. Participants heard their own sounds and those of a stranger from various perspectives. When they listened to their own sounds allocentrically, participants reported that they sensed a presence around them. Additionally, they perceived their own sounds as being closer to themselves compared with those of a stranger. Furthermore, the importance of synchronization between visual and auditory stimuli was suggested in out-of-body illusion experiments that involved the hand, a body part, rather than the entire human body. The rubber-hand illusion was an important psychological phenomenon where a person, through synchronous visual and tactile stimuli, perceived a fake rubber hand as their own. Radziun and Ehrsson19 demonstrated how the rubber hand illusion was boosted by synchronous auditory and visuo-tactile stimuli compared with asynchronous ones. They reported that the congruent auditory stimuli could influence the rubber hand illusion, which indicated its potential to elicit an illusion on our own body cognition.

Therefore, it was hypothesized that audio-visual stimuli could induce out-of-body illusions and affect sense of embodiment. However, previous studies have not investigated out-of-body illusions induced by audio-visual stimuli. If out-of-body illusions could be induced by synchronized audio-visual stimuli, they could be influenced by sensory stimuli not directly related to the body even though they were bodily sensations. This was important for improving VR experiences.

This study was the first to investigate the induction of an out-of-body illusion via synchronized audio-visual stimuli and compare it with that induced by tactile-visual stimuli. We hypothesized that significantly more out-of-body illusions would be induced in the synchronized tactile-visual stimuli condition than asynchronized condition, as with audio-visual stimuli.

We conducted two tasks. The first task provided audio-visual stimuli. This replaced the tactile stimuli with auditory sensations from the experimental design of a previous study9. The second provided tactile-visual stimuli that replicated that of a previous study9. This was done to compare the out-of-body illusion induced by the proposed synchronized audio-visual stimuli with that induced by previously reported synchronized tactile stimuli. In addition, two conditions were applied for each task: synchronized or asynchronized stimuli from two modalities. Thus, four conditions were performed for each participant based on the combination of task and synchronicity differences.

This study prepared two questionnaires as evaluation methods based on a previous study9. Questionnaire 1 enquired the experience during the task and participants responded to items related to the induction of an out-of-body illusion. Questionnaire 2 was supplemental and enquired participants’ degree of anxiety regarding the threat posed to the camera after the task. We analyzed the degree of induction of out-of-body illusion and investigated whether audio-visual stimuli induced out-of-body illusion and differences existed between synchronized audio-visual and tactile-visual stimuli.

Methods

Apparatus

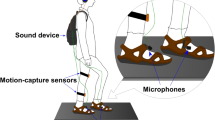

An apparatus (Fig. 1(a)) was constructed and used to allow participants to observe their backs in real time via the HMD.

Experiment description. (a) Apparatus. Participants wore a head-mounted device (HMD) that presented the visual stimuli. In addition, a stereo camera was placed 1 m behind the participant, which captured images behind their back. A program, created in Unity, was executed to present the left and right camera images captured by the stereo camera to the HMD’s left and right eye, respectively. The projected image is presented. (b) Experimental task. The experimenter moved a non-sounding bell in front of the camera at 1 Hz. This movement was also reflected in the image projected on the HMD. The participant saw the bell move as a visual stimulus. Synchronized with this movement, a sounding bell was moved in front of the participant as an audio stimulus. This made it seem as if the sound of the bell could be heard from that position by the movement of the bell in the video. (c) Experimental protocol. In each condition, task and threat to the camera for Questionnaires 2 and 1 were administered. Questionnaire 2 was administered after all the conditions. (d) Overall experiment. (Written informed consent was obtained from the participants in the figures for the publication of identifying information/images in an online open-access publication.).

This experimental set-up was based on the set-up used in Ehrsson’s study9. Participants wore a Meta Quest 2 (Meta Platforms, Inc.) as the HMD to present the visual stimuli. In addition, a stereo camera was placed 1 m behind each participant. The camera was mounted on a tripod to adjust the height of the participant’s eyes parallel to the ground and in the direction they faced. It captured images behind the participant’s back, and a program, created in Unity, was executed to present the left and right camera images captured by the stereo camera to the left and right eye of the HMD, respectively. Latency for displaying images was approximately 100 ms, which was the result of recording and comparing the times taken from both an actual stopwatch and stopwatch viewed through a stereo camera. Since the threshold for synchronized and asynchronized discrimination between the visual, tactile, and auditory sensations was approximately 250 ms, the delay was considered acceptable20.

Experiment tasks

We prepared two tasks. First, a task with audio-visual stimuli. This replaced tactile stimuli with audio stimuli from the experimental design of a previous study9. The second task involved a task with tactile stimuli, which replicated that of a previous study9. This was done to compare the out-of-body illusion induced by the proposed synchronized audio-visual stimuli with that induced by previously reported synchronized tactile stimuli.

The audio-visual stimuli task (Fig. 1(b)) utilized a bell that rang and one that did not, with the experimental setup shown in Fig. 1(c). The experimenter moved the non-sounding bell in front of the camera at 1 Hz. This movement was also reflected in the image projected onto the HMD, and the participants viewed the bell movement as a visual stimulus. Synchronized with this movement, a sounding bell was moved in front of the participants as audio stimulus. Hence, it appeared as if the bell’s sound could be heard from that position by its movement in the video. The sounding bell was not shown in the video.

Tactile-visual stimuli was provided to replicate the previous study’s experiment and compare it with the experimental design of audio-visual stimuli in this study9. This task utilized two sticks. A stick was moved toward the bottom of the camera in a poking motion at 1 Hz. Its movement was reflected in the image projected on the HMD, and participants saw the stick move toward the bottom of the image as a visual stimulus. Synchronized with this movement, the other stick poked their chest as a tactile stimulus. The stick that poked the participant’s chest was not shown in the video.

Experiment conditions

Synchronized conditions were conducted in which visual and tactile stimuli or visual and audio stimuli were presented synchronously (Fig. 2). Furthermore, asynchronized conditions were conducted in which the two stimuli were presented asynchronously. In the synchronous conditions, images captured by a stereo camera were streamed to the HMD in real time. Consequently, the movements of the bells and sticks in the video appeared to be synchronized with the sound of the bells and poking of the chest, respectively. In the asynchronized condition, the video was captured by a stereo camera and streamed to the HMD with a 500 ms delay. Consequently, the movement of the bells and sticks in the video was delayed by 500 ms compared with the sound and poking of the chest, respectively. A previous study reported that out-of-body illusion was not induced under asynchronized conditions in which visual information was delayed by 500 ms. The synchronized/asynchronized discrimination threshold between visual and tactile sensations and between visual and auditory sensations was approximately 250 ms. Therefore, a 500 ms delay was considered sufficient as an asynchronized condition20.

Task descriptions. Side view during the task (left column) and image projected on the HMD (right column). Each stimulus is presented such that the upper and lower images are repeated. (a) The audio-visual stimuli task utilized a bell that could ring and one modified to not ring. The experimenter moved the non-sounding bell in front of the camera at 1 Hz. This movement was also reflected in the image projected on the HMD. The participant saw the bell move as a visual stimulus. Synchronized with this movement, a sounding bell was moved in front of the participant as an audio stimulus. This made it seem as if the sound of the bell could be heard from that position by the movement of the bell in the video. The sounding bell was not shown in the video. (b) Task of providing tactile-visual stimuli replicated the previous study’s experiment and compared it with the experimental design of the audio-visual stimuli in this study. In this task, two sticks were prepared. A stick was moved toward the bottom of the camera in a poking motion at 1 Hz. This movement was reflected in the image projected on the HMD, and participants saw the stick move toward the bottom of the image as a visual stimulus. Synchronized with this movement, the other stick poked the participant’s chest as a tactile stimulus. The stick poking the participant’s chest was not shown in the video. (Written informed consent was obtained from the participants in the figures for the publication of identifying information/images in an online open-access publication.).

The experimental condition combinations were synchronized audio-visual, asynchronized audio-visual, synchronized tactile-visual, and asynchronized tactile-visual. The four combinations of synchronicity and experimental tasks were performed in a random order.

Experiment protocol

First, the stimuli were provided randomly for between 50 and 80 s. Subsequently, a threat was provided by a hammer after the task, as described below. Participants answered questionnaire 1 as an evaluation. These sequences were performed for each condition. At the end of the experiment, participants answered questionnaire 2. Figure 1(d) presents the experimental protocol.

Participants

This study recruited 20 healthy native Japanese speakers (10 males and 10 females) aged 22.6 ± 1.17 years (mean ± standard deviation). Before the experiment, the participants were briefed on the precautions and signed an informed consent form. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles set by the Declaration of Helsinki and its future amendments. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Tokyo Institute of Technology (approval number: A23046). Of the participants, four had errors in the experimental procedures, and data from a re-run of the experiment were used. Furthermore, one participant was excluded from questionnaire 1’s analysis as his comments in the unstructured interview clarified that he had misinterpreted the meaning of the questions.

Evaluations

Evaluation of the induction of out-of-body illusion by stimuli

Questionnaire 1 (Table 1) was administered after each condition to evaluate whether an out-of-body illusion was induced. It was a Japanese translation of a questionnaire developed in a previous study9. As indices for evaluation, the mean values of Q1–Q3 and Q4–Q10 were calculated as “Out-of-Body Illusion Index (OBI Index)” and “Control Index,” respectively21,22,23,24. In total, three main results were expected. First, the OBI Index would be significantly higher in the synchronized conditions than in the asynchronized conditions. Second, the OBI Index would be significantly higher than the Control Index in the synchronized conditions. Third, the Control Index would be negative in all the conditions, regardless of whether an out-of-body illusion was induced.

Evaluation of anxiety regarding the threats

Similar to in the previous study9, participants were threatened after the task to evaluate their anxiety and investigate whether both synchronized audio-visual and tactile-visual stimuli resulted in a higher degree of localization of the body in extra-personal space. Immediately after the task, the bell or stick was replaced with a rubber hammer that swung toward the bottom of the camera. Participants viewed the image of the hammer through the HMD (Fig. 3).

Threat description. Side view during the threat (left column) and image projected on the HMD (right column). A hammer was swung as a threat, as shown in the bottom panel from the top image. To investigate whether participants’ sense of embodiment was generated by the camera’s position, they were provided a threat after the task to assess their anxiety. Immediately after the task presented the stimuli, the bell or stick was replaced by a rubber hammer that swung toward the bottom of the camera. Participants simultaneously viewed the image of this hammer through the HMD. If participants’ sense of embodiment was generated by the position of the stereo camera rather than their own bodies, they should feel more anxious regarding a threat directed at the camera. Thus, we expected significantly higher anxiety responses in the synchronized conditions than asynchronized conditions. (Written informed consent was obtained from the participants in the figures for the publication of identifying information/images in an online open-access publication.).

After all the experimental conditions were completed, questionnaire 2 (Table 2) was administered. Participants reported their anxiety regarding the threat posed by the hammer on a scale from 1 (I was not anxious at all) to 10 (I was the most anxious I could be). If participants’ sense of embodiment was generated by the position of the stereo camera, rather than their own bodies, they would have felt more anxious regarding the threat directed at the camera. Thus, we expected significantly higher anxiety responses in the synchronized conditions than asynchronized conditions.

Results

Evaluation results of the induction of out-of-body illusion by stimuli

We evaluated two aspects of whether an out-of-body illusion was induced in the two conditions, synchronized audio-visual and tactile-visual stimuli, via questionnaires on “out-of-body illusion” and “threat anxiety,” as shown in Fig. 4.

Results of the two questionnaires (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). The display of significant differences between modalities is omitted for readability in (a). Errors bars represent the SEM. (a) Graph presents the results of Questionnaire 1’s “Out-of-Body Illusion Index (OBI Index)” (orange) and “Control Index” (purple) scores (each condition is displayed as bars). For both audio-visual and tactile-visual stimuli, the OBI Index was significantly higher in the synchronized conditions than asynchronized conditions (p = 0.010 and p = 0.011, respectively). The OBI Index was significantly higher in the synchronized conditions than the Control Index (ps < 0.001) in both the tasks. (b) Graph presenting the results of Questionnaire 2. Scores for the synchronized (blue) and asynchronized (orange) conditions in the task for each stimulus are displayed as bars. The degree of anxiety was significantly higher in the synchronized condition than asynchronized condition for both audio-visual stimuli (p = 0.006) and tactile-visual stimuli (p < 0.001).

A Friedman test was performed on the results of questionnaire 1 and confirmed significant differences (p < 0.001). To select a non-parametric or parametric test as the statistical multiple comparison method for the subtest, the normality of the data to be analyzed was confirmed. The Shapiro-Wilk normality test was used to assess the normality of the distribution of the data-set for each experimental condition. Consequently, the null hypothesis that the distribution would be normal was rejected for some datasets (ps < 0.05). Therefore, in this study, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test with Holm-Bonferroni method, a non-parametric statistical test, was used. Concretely, it was performed for multiple comparisons. For both audio-visual and tactile-visual stimuli, the OBI Index was significantly higher in the synchronized condition than asynchronized condition (p = 0.010, p = 0.011, respectively). The OBI Index was significantly higher than the Control Index in the synchronized condition (ps < 0.001) in both the tasks. Furthermore, the Control Index did not differ significantly between the synchronized and asynchronized conditions. Thus, an out-of-body illusion was induced via synchronized audio-visual and tactile-visual stimuli. In addition, under the same conditions, the OBI and Control indices did not differ significantly between tactile-visual and audio-visual stimuli. Hence, synchronized audio-visual stimuli and tactile-visual stimuli similarly induced an out-of-body illusion.

Evaluation results of anxiety regarding the threats

A Friedman test was performed on the results of Questionnaire 2 and confirmed a significant difference (p < 0.001). Furthermore, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test with Holm-Bonferroni method was performed for multiple comparisons. Participants’ degree of anxiety was significantly higher in the synchronized condition than asynchronized condition for both the audio-visual (p = 0.006) and tactile-visual stimuli (p < 0.001).

Supplementary results

The supplementary datasheet includes further detailed analyses. Table S1 presents assumption checks for the statistical analyses. Table S2 presents details on the multiple comparison results in Questionnaire (1) Table S3 and Figure S1 present the results of all the individual questions in Questionnaire 1 for all the conditions. Table S4 presents details on the multiple comparison results in Questionnaire (2) Figures S2 and S3 illustrate the boxplots in Questionnaires 1 and 2, respectively. Tables S5, S6, S7, and S8 presents the correlation analysis results between the experimental conditions in Questionnaires 1 and 2.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate whether synchronized audio-visual stimuli could induce an out-of-body illusion. We hypothesized that significantly more out-of-body illusions would be induced in the synchronized audio-visual condition than asynchronized audio-visual condition. Therefore, tasks with tactile-visual and audio-visual stimuli were conducted to investigate this hypothesis. In each task, the stimuli of the two modalities were either synchronized or asynchronized. Thus, four conditions were assigned to each participant, which combined the task and difference in synchronization. Subsequently, two questionnaires were administered to evaluate the induction of an out-of-body illusion.

Results of questionnaire 1 revealed that the OBI Index, which indicated whether audio-visual and tactile-visual stimuli induced an out-of-body illusion, was significantly higher in the synchronized condition than asynchronized condition. This was consistent with the results of a previous study9,10. Furthermore, the OBI Index was also significantly higher than the Control Index in the synchronized audio-visual and tactile-visual conditions, which was also consistent with previous results9,10. In addition, as hypothesized, the Control Index was not significantly different between the synchronized and asynchronized conditions for either audio-visual or tactile-visual stimuli. In Questionnaire 2, the degree of anxiety was significantly higher in the synchronized conditions than asynchronized conditions for both audio-visual and tactile-visual stimuli, similar to in a previous study9. These results indicated that audio-visual stimuli induced out-of-body illusion, which was consistent with results of previous studies. However, this study was the first to demonstrate that out-of-body illusion could be induced by synchronized audio-visual stimuli without somatic sensation stimuli. Out-of-body illusion was also induced by synchronized tactile-visual stimuli, similar to results of a previous study.

Results of Questionnaire 1 revealed no significant differences between the modalities of stimuli (tactile-visual and audio-visual stimuli) in the OBI and Control indices for the synchronized and asynchronized conditions. Similarly, no significant difference was observed in the anxiety responses in the synchronized and asynchronized conditions in Questionnaire 2, regardless of modality. Therefore, out-of-body illusion was similarly induced via both synchronized tactile-visual and audio-visual stimuli.

Previous studies used tactile stimuli to induce an out-of-body illusion9,11,25. Therefore, stimuli were required to be provided directly to the participant’s body to generate an out-of-body illusion. Conversely, when an out-of-body illusion was induced via synchronized audio-visual stimuli, it could be induced by providing stimuli not required to be directly provided to the participants’ bodies. These results demonstrated that audio-visual stimuli could induce an out-of-body illusion throughout the body. Moreover, previous studies also reported that an out-of-body illusion involved changes in bodily self-location10,26,27. Positive value of the OBI index in this study implied that the study’s variant based on audio-visual synchronized stimulus also involved changes in self-location.

Based on previous studies, what mechanism triggers an out-of-body illusion? This phenomenon may be related to information processing in each sense and their multisensory integration. Multisensory integration is the construction of multiple sensory stimuli, such as what we see, hear, and touch, as coherent rather than separate perceptions. Among the multiple regions of the brain where multisensory integration occurs, the temporoparietal junction is considerably involved in an out-of-body illusion. Previous studies demonstrated that an out-of-body illusion owing to drug abuse, general anesthesia, and sleep were related to the inability to integrate multisensory information from the actual body at the temporoparietal junction8,28. Guterstam et al.29 reported that people experienced an out-of-body illusion in a functional magnetic resonance imaging study, which scanned human brain activity. They suggested that involvement of two brain networks was associated with changes in body ownership and self-location, respectively. Illusory self-location was associated with activity in the hippocampus and posterior cingulate, retro-splenial, and intraparietal cortices. Furthermore, body ownership was associated with premotor-intraparietal activity. These brain regions could also be involved in an out-of-body illusion induced by synchronous audio-visual stimulation.

Previous studies have not thoroughly investigated the neuroscientific aspects of an out-of-body illusion induced by audio-visual synchronous stimulation. Therefore, to address this issue, we considered previous research on out-of-body illusion via visual-somatosensory synchronous stimulation. In an out-of-body illusion based on visual-somatosensory synchronous stimulation, different neural information processing systems in the brain managed visual and somatosensory stimuli. The illusion was elicited from their multisensory integration12,14,16. Therefore, when an out-of-body illusion was induced by synchronous visual-somatosensory stimulation, visual and somatosensory information were initially processed separately in the nervous system and subsequently integrated. Next, we considered an out-of-body illusion based on audio-visual synchronous stimulation according to previous findings. Specifically, visual information is processed in the visual cortex in the occipital lobe, while auditory information is processed in the auditory cortex in the temporal lobe. Furthermore, the temporoparietal junction, which is associated with an out-of-body illusion, integrates visual and auditory inputs30. When visual and auditory stimuli are presented synchronously31 and from the same location32, more multisensory neurons involved in multisensory integration are activated. This suggests that visual and auditory information may be closely related. Thus, in an out-of-body illusion based on audio-visual synchronous stimulation, audio-visual synchronous stimulation may be processed separately and subsequently integrated, as with visual-somatosensory synchronous stimulation.

Further investigation is required to determine the features of audio-visual stimuli that are sufficient to induce an out-of-body illusion. Our results suggested that spatiotemporally matched audio-visual stimuli could have sufficient stimulus features to induce an out-of-body illusion. A previous study suggested that humans perceived time in near and far space differently and subsequently distance to the signal source affected sound33. Hence, humans may experience a sense of embodiment when both the visual and auditory stimulus sources are spatiotemporally consistent. Specific characteristics of simultaneous audio-visual stimuli that elicit an out-of-body illusion will be further elucidated in future research based on this study’s findings.

This study has some limitations. First, only the questionnaire results were included and no objective indirect tests were conducted. Specifically, we did not measure threat-evoked skin conductance responses (SCR) during the threat procedure and solely relied on fear ratings. However, fear ratings were correlated with SCR and brain activity in areas related to fear and anticipation of pain9,29,34,35. Previous studies reported that fear reports, such as when illusory owned body parts were physically threatened in body ownership illusions, were correlated with objective physiological measures of fear and pain anticipation responses. The more intensely people experienced a body ownership illusion, the greater the reported fear when the illusory body was threatened. Moreover, the stronger the fear, the more pronounced the threat-evoked skin conductance responses (SCR) and threat-evoked BOLD activation in areas related to fear and pain anticipation, such as the anterior cingulate cortex and insular cortex9,29,34. Therefore, a fear report was an index of the emotional defense reactions triggered by threats to one’s own body or what was perceived as one’s own body in bodily illusions. Fear ratings are a valid indicator of illusory changes in body ownership and self-location4. Future studies should further verify this phenomenon based on questionnaires and physiological indicators, such as the SCR. Additionally, evaluation of the sense of self-location via measurement methods other than questionnaires may also be useful to further investigate the phenomenon of an out-of-body illusion10,25,26.

This study’s paradigm was an out-of-body illusion based on a first-person perspective. Other studies investigated out-of-body illusions based on a third-person perspective via a VR environment with a VR HMD36,37. These studies demonstrated that visual and tactile sensations induced significantly more out-of-body illusions when stimuli were provided synchronously than asynchronously. Another study reported that sense of embodiment changed when the movements of the virtual body were synchronized with those of the participant’s real body25. Ehrsson’s9 paradigm involved multisensory integration from a first-person perspective, which resulted in a strong perceptual illusion of body ownership and self-location. Conversely, Lenggenhager’s36 paradigm involved visuo-tactile stimulation from a third-person perspective, which led to a weaker cognitive feeling of illusory self-identification. Full-body illusions experienced from the first-person perspective were significantly stronger than those experienced from the third-person perspective38,39,40,41,42. Future studies should verify the experimental conditions based on the third-person perspective.

Conclusion

This study aimed to investigate whether synchronized audio-visual stimuli induced an out-of-body illusion and compare it with synchronized tactile-visual stimuli. Specifically, based on Ehrsson’s experimental design9, participants sat in a chair and observed their own back with a stereo camera of the HMD. In the synchronized audio-visual stimuli condition, a sound-making bell was rung in front of the participant’s body to provide an auditory stimulus. Simultaneously, a silent bell was rung in front of the stereo camera in synchronization to provide a visual stimulus. In the synchronous tactile-visual stimuli condition as the control condition, a tactile stimulus was a stick that poked the participant’s chest, and a visual stimulus was evoked by moving the stick in front of the stereo camera in synchronization to provide a visual stimulus. As further control conditions, asynchronized audio-visual and tactile-visual stimuli conditions were also implemented. Consequently, it was indicated that the synchronized tactile-visual stimuli condition induced an out-of-body illusion, similar to in previous studies. Surprisingly and importantly, an out-of-body illusion was induced under the synchronized audio-visual stimuli condition. This suggested for the first time that the out-of-body illusion, as an illusion related to the sense of embodiment that targeted the entire body, could be induced by synchronized audio-visual stimuli alone, without a tactile stimulus. New findings will contribute to elucidating the mechanism of out-of-body illusions and development of applications based on out-of-body illusions, such as in virtual, augmented, and mixed reality.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Tachi, S., Sato, M. & Hirose, M. & The virtual reality society of Japan. In Virtual Reality Gaku (CORONA Publishing Co., Ltd, 2011).

Tajadura-Jiménez, A. et al. Action sounds recalibrate perceived tactile distance. Curr. Biol. 22, R516–R517 (2012).

Tachi, S. & Telexistence Past, present, and future in Virtual Realities: International Dagstuhl Seminar, Dagstuhl Castle, Germany, June 9–14, Revised Selected Papers 229–259 (2015). (2013).

Ehrsson, H. H. Multisensory processes in body ownership. In Multisensory Perception: From Laboratory to Clinic (eds Sathian, K. & Ramachandran, V. S.) 179–200 (Academic Press, 2020).

Ehrsson, H. H. & Bodily illusions. In The Routledge Handbook of Bodily Awareness (eds A. J. T., Alsmith & M. R. Longo) 201–229 (Routledge, 2023).

Guy, M., Normand, J. M., Jeunet-Kelway, C. & Moreau, G. The sense of embodiment in virtual reality and its assessment methods. Front. Virtual Real. 4, 1141683 (2023).

Schettler, A., Raja, V. & Anderson, M. The embodiment of objects: Review, analysis, and future directions. Front. Neurosci. 13, 1332 (2019).

Bünning, S. & Blanke, O. The out-of body experience: Precipitating factors and neural correlates. Prog. Brain Res. 150, 331–350 (2005).

Ehrsson, H. H. The experimental induction of out-of-body experiences. Science 317, 1048 (2007).

Guterstam, A. & Ehrsson, H. H. Disowning one’s seen real body during an out-of-body illusion. Conscious Cognit. 21, 1037–1042 (2012).

Petkova, V. I. & Ehrsson, H. H. If I were you: Perceptual illusion of body swapping. PLoS ONE 3, e3832 (2008).

Matsumiya, K. Separate multisensory integration processes for ownership and localization of body parts. Sci. Rep. 9, 652 (2019).

Blanke, O., Slater, M. & Serino, A. Behavioral, neural, and computational principles of bodily self-consciousness. Neuron 88, 145–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.029 (2015).

Chancel, M., Ehrsson, H. H. & Ma, W. J. Uncertainty-based inference of a common cause for body ownership. Elife 11, e77221. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.77221 (2022).

Ehrsson, H. H. The concept of body ownership and its relation to multisensory integration. In The New Handbook of Multisensory Processes (ed Stein, B. E.) 179–200. (MIT Press, 2012).

Kilteni, K., Maselli, A., Kording, K. P. & Slater, M. Over my fake body: Body ownership illusions for studying the multisensory basis of own-body perception. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9, 141 (2015).

Kitagawa, N. & Igarashi, Y. Tickle sensation induced by hearing a sound. Jpn. J. Psychonomic Sci. 24, 121–122 (2005).

Roel Lesur, M., Bolt, E., Saetta, G. & Lenggenhager, B. The monologue of the double: Allocentric reduplication of the own voice alters bodily self-perception. Conscious Cognit. 95, 103223 (2021).

Radziun, D. & Ehrsson, H. H. Auditory cues influence the rubber-hand illusion. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 44, 1012–1021 (2018).

Fujisaki, W. & Nishida, S. Audio–tactile superiority over visuo–tactile and audio–visual combinations in the temporal resolution of synchrony perception. Exp. Brain Res. 198, 245–259 (2009).

Pamment, J. & Aspell, J. E. Putting pain out of mind with an ‘out of body’ illusion. Eur. J. Pain. 21, 334–342 (2017).

Bergouignan, L., Nyberg, L. & Ehrsson, H. H. Out-of-body memory encoding causes third-person perspective at recall. J. Cognit. Psychol. 34, 160–178 (2022).

Palluel, E., Aspell, J. E., Lavanchy, T. & Blanke, O. Experimental changes in bodily self-consciousness are tuned to the frequency sensitivity of proprioceptive fibres. Neuroreport 23, 354–359 (2012).

Kaplan, R. A. et al. Is body dysmorphic disorder associated with abnormal bodily self-awareness? A study using the rubber hand illusion. PLoS ONE 9, e99981 (2014).

Gonzalez-Franco, M., Perez-Marcos, D., Spanlang, B. & Slater, M. The contribution of real-time mirror reflections of motor actions on virtual body ownership in an immersive virtual environment. In 2010 IEEE Virtual Reality Conference (VR) 111–114 (2010).

Guterstam, A., Abdulkarim, Z. & Ehrsson, H. H. Illusory ownership of an invisible body reduces autonomic and subjective social anxiety responses. Sci. Rep. 5, 9831 (2015).

Guterstam, A. et al. Decoding illusory self-location from activity in the human hippocampus. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9, 412 (2015).

Blanke, O. & Arzy, S. The out-of-body experience: Disturbed self-processing at the temporo-parietal junction. Neuroscientist 11, 16–24 (2005).

Guterstam, A., Bjornsdotter, M., Gentile, G. & Ehrsson, H. H. Posterior cingulate cortex integrates the senses of self-location and body ownership. Curr. Biol. 25, 1416–1425 (2015).

Davis, M. H. Chapter 44 - The neurobiology of lexical access. In Neurobiology of Language (eds Hickok, G. & Small, S. L.) 541–555 (Academic Press, 2016).

Meredith, M. A., Nemitz, J. W. & Stein, B. E. Determinants of multisensory integration in superior colliculus neurons. I. Temporal factors. J. Neurosci. 7, 3215–3229 (1987).

Meredith, M. A. & Stein, B. E. Spatial factors determine the activity of multisensory neurons in cat superior colliculus. Brain Res. 365, 350–354 (1986).

Petrizzo, I. et al. Time and numerosity estimation in peripersonal and extrapersonal space. Acta. Psychol. 215, 103296 (2021).

Gentile, G., Guterstam, A., Brozzoli, C. & Ehrsson, H. H. Disintegration of multisensory signals from the real hand reduces default limb self-attribution: An fMRI study. J. Neurosci. 33, 13350–13366 (2013).

Lush, P. Demand characteristics confound the rubber hand illusion. Collabra: Psychol. 6, 22 (2020).

Lenggenhager, B., Tadi, T., Metzinger, T. & Blanke, O. Video ergo sum: Manipulating bodily self-consciousness. Science. 317, 1096–1099 (2007).

Nakul, E., Orlando-Dessaints, N., Lenggenhager, B. & Lopez, C. Measuring perceived self-location in virtual reality. Sci. Rep. 10, 6802 (2020).

Gorisse, G., Christmann, O., Amato, E. A. & Richir, S. First- and third-person perspectives in immersive virtual environments: Presence and performance analysis of embodied users. Front. Robot AI. 4, 1–33 (2017).

Maselli, A. & Slater, M. The building blocks of the full body ownership illusion. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7, 83 (2013).

Petkova, V. I. et al. From part- to whole-body ownership in the multisensory brain. Curr. Biol. 21, 1118–1122 (2011).

Petkova, V. I., Khoshnevis, M. & Ehrsson, H. H. The perspective matters! Multisensory integration in ego-centric reference frames determines full-body ownership. Front. Psychol. 2, 35 (2011).

Maselli, A. & Slater, M. Sliding perspectives: Dissociating ownership from self-location during full body illusions in virtual reality. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8, 693 (2014).

Romano, J. et al. Exploring methods for evaluating group differences on the NSSE and other surveys: Are the t-test and Cohen’s d indices the most appropriate choices? In Annual Meeting of the Southern Association for Institutional Research 1–51 (2006).

Meissel, K. & Yao, E. S. Using Cliff’s delta as a non-parametric effect size measure: An accessible web app and R tutorial. Pract. Ass. Res. Eval 29, 2 (2024).

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number 22K17630, Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) CREST Grant Number JPMJCR21C5, and JST COI-NEXT Grant Number JPMJPF2101.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YE, HU, & YM designed the study. YE & HU collected the data, performed the analyses, and wrote the manuscript. YE, HU, & YM reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Euchi, Y., Uchitomi, H. & Miyake, Y. Audio visual stimuli based out of body illusion. Sci Rep 14, 24540 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74904-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74904-5