Abstract

Notwithstanding the latest advancements in anticancer therapy, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) remains a prominent contributor to cancer-associated mortality worldwide. Therefore, effective anti-cancer agents are required for the treatment of NSCLC. We previously demonstrated that the natural alkaloid evodiamine efficiently suppressed lung cancer cells and lung cancer stem-like cell populations by suppressing heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70). This finding inspired us to formulate evodiamine-based anti-cancer compounds against NSCLC. In this study, we synthesized a series of evodiamine derivatives with substitutions at the N14 position. EV206 was chosen for further study because it was the most effective among the 22 evodiamine derivatives at stopping H1299 cell growth. EV206 treatment efficiently suppressed cell viability and colony formation in both attached cells and in soft agar, even in those carrying drug resistance, by inducing apoptosis. The effectiveness of EV206 is approximately ten times greater than that of evodiamine. Normal cell viability was marginally affected by EV206 treatment. Additionally, EV206 efficiently decreased the cancer stem cell (CSC) population in the NSCLC cells. EV206 reduced the growth of H460 xenograft tumors without exhibiting toxic effects. These data implied that EV206 has the potential to be an effective Hsp70-targeting anticancer drug with low toxicity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lung cancer is a prevalent type of cancer in terms of both occurrence and death worldwide1. A recent report of global cancer statistics demonstrated that in 2020, approximately 2.2 million individuals received a new lung cancer diagnosis, and approximately 1.8 million fatalities were attributed to lung cancer patients1. There are two main types of lung cancer: non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC). NSCLC is the major lung cancer type, representing 80–85% of lung cancer diagnostic cases2. Owing to the innovative achievements in therapy development for NSCLC, including those using molecular targeted therapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors3, there has been a steady improvement in the 5-year survival rate of NSCLC patients4. However, the emergence of drug resistance, side effects, and toxicity has caused therapeutic failure in cancer therapy for solid tumors, including NSCLC5. In addition, patients with lung cancer are often diagnosed in later stages, and they exhibit limited responsiveness to clinically available therapeutic regimens5. Hence, the creation of new anticancer hits or candidates that offer improved efficacy and reduced toxicity is crucial for lung cancer treatment.

For drug development, natural products have provided a structural backbone, and compounds isolated from natural products or synthesized based on natural product-derived substances have been utilized as anticancer drugs6. One of these compounds is evodiamine, an indoloquinazolidine alkaloid derived from Evodia rutaecarpa7. Previously, a range of biological actions of evodiamine, including anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, cardioprotective, neuroprotective, and anticancer effects, has been demonstrated7. We provided preclinical evidence that evodiamine suppresses lung cancer cells and lung cancer stem cells (CSCs) by disrupting the function of the heat shock protein (HSP) system, specifically heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70), via ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation8. These findings suggest that evodiamine is an attractive candidate for the development of novel anticancer drugs.

Hsp70, a component of the HSP system, plays an important role in protecting cells from harmful environmental stimuli that disrupt the mature folding and stability of proteins9and in regulating innate or adaptive immunity10. Accordingly, interruption of the HSP system results in several diseases such as neurodegenerative diseases and diabetes9,11. In addition to its role in cellular homeostasis and immunity, Hsp70 is closely involved in the hallmarks of cancer owing to the oncogenic impact of various client proteins of the HSP system11. Studies have shown that deregulation of Hsp70 induces cancer development and progression and anticancer drug resistance by promoting cell survival, metastasis, and invasion of cancer cells, shaping cancer immunity, and stimulating tumor angiogenesis9,11. Additionally, several therapeutics targeting Hsp70, categorized as monoclonal antibodies and small-molecule inhibitors, have been developed and evaluated for their anticancer efficacy in preclinical studies and clinical trials9,11. However, none of these have successfully entered clinical use12.

Since Hsp70 is crucial in carcinogenesis and cancer progression, along with the absence of clinically accessible Hsp70-targeting inhibitors for anticancer therapeutics12, we developed evodiamine-based anticancer Hsp70 inhibitors. Previous structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies of evodiamine suggest that the C10-position of the evodiamine A-ring is essential for its anticancer effects13,14. Indeed, we also demonstrated that EV408, an evodiamine derivative with a substitution at the C10 position, displayed significantly enhanced effectiveness in reducing NSCLC cell viability in comparison to evodiamine15.

Along with continuous efforts to develop novel antitumor evodiamine derivatives15, the present study developed 22 synthetic N14-substituted evodiamine derivatives and examined their efficacy for the procurement of the efficacious compound. We identified EV206 as the most potent evodiamine derivative, with approximately ten times greater efficacy than evodiamine. EV206 efficiently blocked cell viability and colony formation in NSCLC cells, both therapy-naïve and therapy-resistant cells, by causing apoptotic cell death. In addition to its anti-CSC effects, EV206 suppressed H460 tumor xenograft growth. Moreover, the activity of Hsp70 was efficiently downregulated by EV206 treatment through its ability to interact with Hsp70 and cause proteasomal degradation of Hsp70. These findings indicate that EV206 is a novel Hsp70 blocker with wide-ranging effectiveness against NSCLC.

Results

Synthesis of evodiamine derivatives

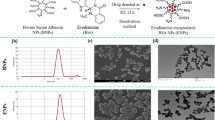

Based on our previous synthetic method for evodiamine8, we designed and synthesized a series of N14-substituted evodiamine derivatives, EV201-EV220 (Fig. 1a). In our synthetic strategy, the main indoloquinazolidine skeleton was constructed via cyclco-condensation between dihydro-β-carboline 2 and isatoic anhydride 4. Dihydro-β-carboline compound 2 was synthesized from tryptamine in high yield in two steps: N-formylation followed by intramolecular Bischler–Napieralski-type cyclization. Another coupling partner, isatosic anhydride, was obtained by the reaction of anthranilic acid with triphosgene. To introduce various substituents to the amine, we applied the corresponding alkyl halides to simple isatosic anhydride 3 under basic conditions. After obtaining N-substituted isatosic anhydride 4, it was reacted with 2 to synthesize 20 evodiamine derivatives, which were diversified at the N14 position. We further synthesized two derivatives to investigate the effect of the D-ring on anticancer activity. The coupling of carboline 2 with salicyl chloride afforded oxa-derivative EV221, and the reduction of the D-ring amide group in evodiamine using LiAlH4 yielded the carbonyl-removed derivative EV222. The structures of all the synthesized evodiamine (EV) derivatives are shown in Fig. 1b, and their purity was confirmed by HPLC to be above 95.0%. Detailed synthetic procedures and characterization of these compounds are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Outline of synthetic procedures ofN14-substituted evodiamine derivatives and structures of EV201-EV222. (a) Scheme of evodiamine derivative synthesis. (a) ethyl formate, 80 °C, 6 h, quant.; (b) POCl3, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 4 h, 94%; (c) triphosgene, THF, 50 °C, 3 h, 95%; (d) RX, DIPEA, DMAc, 40 °C, overnight, 50–88%; (e) CH2Cl2, 50 °C, 6 h, 14–98%; (f) CH2Cl2, r.t., 12 h, 54%; (g) LiAlH4, THF, r.t., 12 h, 64%. (b) Structures of EV201-EV202.

SAR analysis of evodiamine derivatives on the inhibition of NSCLC cell viability

To analyze the SAR for the inhibition of NSCLC cell viability, we first evaluated the inhibitory effects of the synthesized compounds (EV201-EV222) on H1299 cell viability (Fig. 2a). The demethylated evodiamine EV200 and D-ring-modified derivatives EV221 and EV222 lost their anticancer activity against NSCLC cells. The acylated derivative EV204 showed weak inhibitory effects on NSCLC cells only at high doses. Regardless of the various substituents on the benzyl group, most derivatives that contained the benzyl group at the N14 position did not exhibit significant anticancer activity. A few derivatives (EV209, EV210, EV212, and EV215) showed weak anticancer activity against NSCLC cells at concentrations > 5 µM. Interestingly, propargyl- and allyl-substituted derivatives (EV205 and EV206, respectively) demonstrated significant efficacy in reducing H1299 cell viability. Three derivatives (EV217–EV219), which have additional methyl groups on the allyl and propargyl substituents, appeared to maintain this inhibitory effect. However, the cinnamyl-substituted derivative (EV220) lost its antitumor activity, probably because of its bulky phenyl group. Hence, it is likely that the unsaturated substituent at the N14 position plays an essential role in the suppression of NSCLC cell viability.

Identification of EV206 as the most efficacious evodiamine derivative impeding NSCLC cell viability. (a) The effect of 22 evodiamine derivatives on H1299 cell viability was assessed using a crystal violet assay (mean ± SD, n = 5 or 6/group). The cells were treated with these evodiamine derivatives for 48 h. (b) The effectiveness of evodiamine and four evodiamine derivatives in inhibiting H1299 and H460 cell viability was determined by a crystal violet assay after treating cells with these compounds for 48 h (mean ± SD, n = 4–6/group). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test by comparison with the vehicle-treated control group (EV206 0 µM).

We next assessed the suppressive activity of four efficacious evodiamine derivatives (EV205, EV206, EV217, and EV218) on the viability of H1299 and H460 cells in comparison with that of evodiamine. To obtain a more potent compound than evodiamine, we carried out an evaluation at concentrations below 1 µM. As shown in Fig. 2b, EV206 exhibited the most pronounced inhibitory effect on H1299 and H460 cell viability, and the efficacy of EV206 was approximately 10-fold higher than that of evodiamine. Based on these results, we selected EV206 for further investigation.

Suppressive effects of EV206 on cell viability and colony-forming ability of NSCLC cells by triggering apoptotic cell death

The efficacy of EV206 on cell viability and colony formation under both attached and anchorage-independent culture conditions was assessed in NSCLC cells (H1299, H460, H226B, A549, and PC9 cells). The viability of NSCLC cells was substantially inhibited by EV206 treatment, as indicated by IC50 values below 1 µM (Fig. 3a; Table 1). Additionally, EV206 efficiently suppressed the growth of NSCLC cell colonies in both anchorage-dependent (AD) (Fig. 3b) and anchorage-independent (AID) (Fig. 3c) culture settings. These inhibitory effects of EV206 were accompanied by triggering apoptosis, as evidenced by an increase in the sub-G1 phase cell population (Fig. 3d) and a dose-dependent induction of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and caspase-3 cleavage (Fig. 3e). We determined the pro-apoptotic effect of EV206 and compared it with that of evodiamine. Treatment with evodiamine (0.5 µM) barely induced the cleavage of PARP and caspase-3 (Fig. 3f), which was consistent with the minimal effect of the same concentration of evodiamine on the viability of NSCLC cells (Fig. 2b). In contrast, EV206 markedly increased the levels of cleaved PARP and caspase-3, indicating that EV206 had a superior pro-apoptotic effect compared to evodiamine (Fig. 3f).

Suppression of NSCLC cell viability and colony-forming ability by EV206 treatment via induction of apoptotic cell death. (a) The efficacy of EV206 in suppressing NSCLC cell viability was examined using a crystal violet assay (mean ± SD, n = 5 or 6/group). Cells were treated with various concentrations of EV206 for 48 h. (b) The effect of EV206 on NSCLC cell colony formation under anchorage-dependent (AD) conditions was examined using an AD colony formation assay (mean ± SD, n = 3/group). (c) The effect of EV206 on NSCLC cell colony formation in anchorage-independent (AID) settings was assessed using a soft agar AID colony formation assay (mean ± SD, n = 3–5/group). (d, e) The effect of EV206 on apoptosis of NSCLC cells was assessed by cell cycle analysis using flow cytometry (d) and western blotting (e). (e, bottom) Western blotting results were quantified using densitometric analysis (mean ± SD, n = 3/group). The cells were treated with increasing concentrations of EV206 for 48 h. (f) The pro-apoptotic effect of EV206 (0.5 µM) in comparison with that of evodiamine (Evo, 0.5 µM) was determined by western blotting. The cells were treated with these compounds for 48 h. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test by comparison with the vehicle-treated control group (EV206 0 µM).

EV206-induced suppression of viability and colony formation of NSCLC cells with acquired resistance to chemotherapy or molecular targeted therapy via apoptotic cell death

We examined the effects of EV206 on NSCLC cells carrying acquired resistance to chemotherapy (cisplatin-resistant H1299 [H1299/CsR], pemetrexed-resistant H1299 [H1299/PmR], and paclitaxel-resistant H460 [H460/PcR] and H226B [H226B/PcR] cells) or an epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (EGFR TKI, erlotinib-resistant PC9 [PC9/ER] cells)15 in regards of their viability and colony formation in AD and AID settings. EV206 had a dose-dependent negative effect on the viability of these cells (Fig. 4a). The effects of EV206 on parental cells and their subpopulations that acquired resistance to chemotherapeutics or EGFR TKI were comparable (Table 1). In addition, EV206 considerably suppressed colony formation by drug-resistant NSCLC cells in both AD (Fig. 4b) and AID (Fig. 4c) culture settings. Furthermore, treatment with EV206 elevated the levels of sub-G1 phase cell populations (Fig. 4d) and a concentration-dependent induction of cleavage of PARP and caspase-3 (Fig. 4e), indicating the pro-apoptotic effects of EV206 on these drug-resistant NSCLC cells. In addition, consistent with the effects in therapy-naïve cells, EV206 increased PARP and caspase-3 cleavage compared to evodiamine (Fig. 4f). Collectively, these results indicate that EV206 exerts anticancer effects against both drug-naïve and drug-resistant NSCLC cells by inducing apoptosis.

Inhibition of cell viability and reduction of colony growth of NSCLC cells resistant to anticancer drugs by eliciting apoptosis by EV206 treatment. (a) The efficacy of EV206 in reducing the viability of H1299/CsR (cisplatin-resistant), H1299/PmR (pemetrexed-resistant), H460/PcR (paclitaxel-resistant), H226B/PcR (paclitaxel-resistant), and PC9/ER (erlotinib-resistant) cells was examined using a crystal violet assay (mean ± SD, n = 5 or 6/group). Cells were treated with various concentrations of EV206 for 48 h. (b) The effect of EV206 on colony formation by drug-resistant NSCLC cells under anchorage-dependent (AD) conditions was examined using an AD colony formation assay (mean ± SD, n = 3/group). (c) The effect of EV206 on colony formation by drug-resistant NSCLC cells in an anchorage-independent (AID) setting was assessed using a soft agar AID colony formation assay (mean ± SD, n = 3–5/group). (d, e) The effect of EV206 on apoptosis in drug-resistant NSCLC cells was assessed by cell cycle analysis using flow cytometry (d) and western blotting (e). (e, bottom) Western blotting results were quantified using densitometric analysis (mean ± SD, n = 3/group). The cells were treated with various concentrations of EV206 for 48 h. (f) The pro-apoptotic effect of EV206 (0.5 µM) in comparison with that of evodiamine (Evo, 0.5 µM) was determined by western blotting. Cells were treated with these compounds for 48 h. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test by comparison with the vehicle-treated control group (EV206 0 µM).

EV206-mediated inhibition of CSC-like phenotypes in NSCLC cells

Considering the anti-CSC effect of evodiamine8, we assessed whether EV206 could downregulate the CSC-like characteristics of NSCLC cells. The sphere formation assay revealed the inhibitory activity of EV206 on NSCLC sphere formation, with the degree of inhibition dependent on concentration (Fig. 5a). Additionally, EV206 decreased aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity, a known CSC marker16, in NSCLC cells (Fig. 5b). Moreover, EV206 caused a marked decrease in the expression of CSC-related markers, such as POU5F1 (the gene encoding Oct4), NANOG, and SOX217 (Fig. 5c). Collectively, these results suggest that EV206 inhibits CSC-associated phenotypes in NSCLC cells.

Anti-CSC activity EV206 in NSCLC cells. (a) Impact of EV206 on NSCLC sphere formation, as determined by the sphere-forming assay (mean ± SD, n = 4 or 5/group). (b) Effect of EV206 on ALDH activity in NSCLC cells. Cells were treated with vehicle (DMSO) or EV206 for 48 h. (c) EV206-mediated regulation of CSC-associated markers, as determined by real-time PCR (mean ± SD, n = 3/group). Vehicle (DMSO)- or EV206-treated spheres were collected and subjected to RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and real-time PCR analysis. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test (a) or a two-tailed Student’s t-test (c) by comparison with the vehicle-treated control group (EV206 0 µM).

Disruption of Hsp70 protein stability by EV206 treatment through interaction with the Hsp70 N-terminal domain

Based on our previously published literature on the regulatory activity of evodiamine on the HSP system by targeting HSP70 expression8, we assessed the impact of EV206 on the levels of Hsp70, Hsp90, and Akt, a representative client protein of the HSP system function. EV206 effectively decreased the levels of Hsp70 and Akt proteins in NSCLC cells but did not alter the expression of Hsp90 (Fig. 6a). In addition, our previous research showed that evodiamine destabilizes Hsp70 through ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation8. Hence, we examined the ability of EV206 to reduce the protein stability Hsp70 via the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Indeed, co-treatment with MG132, a proteasome inhibitor, markedly blunted the EV206-induced downregulation of Hsp70 (Fig. 6b). Therefore, EV206 seems to destabilize Hsp70 by promoting Hsp70 degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Additionally, we performed a drug affinity responsive target stability (DARTS) assay to verify Hsp70 as a target of EV206. We used full-length Hsp70 (FL) and two shortened mutant forms of Hsp70 (the N-terminal domain [N] and the C-terminal domain [C]) for the DARTS array. EV206 strongly slowed down the breakdown of FL and N by proteases, but did not change the breakdown of C. These results implied that EV206 binds to both FL and N (Fig. 6c). We further substantiated the binding of EV206 to N using a fluorescence-based equilibrium-binding assay18. The Kd values for the N and C were 16.60 µM and 42.27 µM, respectively (Fig. 6d), suggesting that EV206 has a greater capacity to bind to the N. These findings suggest that EV206 inhibits Hsp70 by interacting with its Hsp70 N-terminal domain and promoting proteasomal degradation.

Suppression of Hsp70 function by EV206 treatment by reducing Hsp70 stability via Hsp70 N-terminal domain binding. (a, b) Western blot analysis showing the capacity of EV206 to regulate Hsp70, Hsp90, and Akt expression (a) and Hsp70 expression with or without treatment with MG132 (10 µM) (b). For the experiment in panel (a), cells were incubated with vehicle (DMSO) or the indicated concentrations of EV206 for 48 h. For the experiment in panel (b), the cells were incubated with vehicle (DMSO) or EV206 (0.1 and 0.25 µM) for 48 h and additionally treated with MG132 (10 µM) for 6 h if necessary. Graphs in panels (a) and (b) depict the quantification of western blotting results by densitometric analysis (mean ± SD, n = 3/group). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test by comparison with the vehicle-treated control group (EV206 0 µM). (c) DARTS assay to evaluate EV206 binding to full-length Hsp70 (FL), Hsp70 N-terminal domain (N), or Hsp70 C-terminal domain (C). (d) Fluorescence-based equilibrium binding assay to evaluate EV206 binding to Hsp70 N-terminal domain (Hsp70 N) or Hsp70 C-terminal domain (Hsp70 C).

Antitumor effect and minimal toxicity of EV206

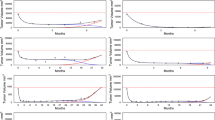

We examined the suppressive effect of EV206 on tumor growth in a tumor xenograft model using H460 cells. EV206 inhibited the increase in tumor volume in the H460 tumor xenograft model (Fig. 7a). Importantly, the administration of EV206 did not cause any detectable changes in the body weight of the mice (Fig. 7b). These findings suggest an inhibitory effect of EV206 on H460 tumor growth, with no overt toxicity. Furthermore, EV206 had a minimal impact on normal cell viability when evaluating normal cells originating from several organs, such as the retina (RPE), lung (MLE12), and liver (NCTC 1469) (Fig. 7c). These data indicate the in vivo antitumor effect of EV206 and its reduced toxicity in in vitro and in vivo models.

In vivo antitumor effect of EV206 and its limited toxicity. (a) Regulation of H460 tumor xenograft growth in response to intraperitoneal vehicle or EV206 (10 mg/kg) treatment (mean ± SD, n = 6/group). (b) Changes in body weight between vehicle- and EV206-treated mice (mean ± SD, n = 6/group). (c) Impact of EV206 on normal cell viability, as determined by the MTT assay (mean ± SD, n = 5 or 6/group). The cells were treated with vehicle (DMSO) or EV206 for 48 h. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, determined by a two-tailed Student’s t-test (a) or one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test (c) by comparison with the vehicle-treated control group (vehicle or EV206 0 μM).

Discussion

The HSP system is essential for carcinogenesis, cancer progression, and anticancer drug resistance. It acts as a molecular chaperone, ensuring the stability of different client oncoproteins12,19. Therefore, it is imperative to develop agents that specifically target HSP with minimal toxicity. In light of our earlier research that showed the potential of evodiamine as an inhibitor of Hsp70 in cancer treatment8, we aimed to discover novel anticancer evodiamine derivatives targeting Hsp70 with enhanced effectiveness and reduced toxic effects. Among the 22 evodiamine derivatives, EV206 showed the strongest capacity to limit the growth and formation of NSCLC cell colonies. These effects were also observed in cells that were resistant to chemotherapy or EGFR-TKI treatment, and these effects were achieved by triggering apoptosis. Additionally, EV206 suppressed CSC-like characteristics of NSCLC cells. EV206 hindered the activity of Hsp70 by attaching to the N-terminal region of Hsp70, causing instability in the Hsp70 protein. Moreover, EV206 efficiently reduced tumor xenograft growth in vivo without causing any noticeable toxicity. These findings highlight the potential of EV206 as an efficacious anticancer drug that targets Hsp70 and suppresses NSCLC cells as well as their CSC-like populations.

Evodiamine is a natural indoloquinazolidine alkaloid with anticancer activity7. Thus, several medicinal chemists have produced and assessed evodiamine derivatives for SAR to produce agents with improved anticancer activity13,14. Most studies have focused on the diversification of both benzenes in evodiamines (rings A and E, Fig. 1a). Based on the role of the A-ring of evodiamine, especially the C10-position, in the anticancer effect, we synthesized C10-substituted derivatives and showed that the C10-hydroxy substituted derivative EV408 inhibited NSCLC cell viability better than evodiamine15. To develop efficacious anticancer evodiamine derivatives, we synthesized several N14-substituted evodiamine derivatives. SAR studies of N13 substituents have been reported in the literature20. However, compared to other regions of evodiamine, transformation of the N14 position has been challenging, limiting the development of N14-substituted derivatives. Recently, Wang et al. developed N14-aryl-substituted evodiamine derivatives and analyzed their anticancer activity, although only with aromatic N14 substituents21. The SAR of the compounds produced for anticancer activity suggested that unsaturated substituents at the N14 position, such as propargyl and allyl groups, are critical for exerting strong cytotoxicity against NSCLC cells. Several novel evodiamine N14-substituents exhibit significant anticancer properties. These findings provide important SAR information for further design of evodiamine derivatives.

The most efficacious N14-allyl substituted evodiamine derivative, EV206, displayed the most efficacious activity in the inhibition of cell viability, formation of colonies in both attached and anchorage-independent settings, and Hsp70 function in NSCLC cells, with reduced toxicity in normal cells. EV206 exhibited an approximately 10-fold increase in efficacy relative to evodiamine. It has been known that drug resistance is the leading cause of the failure of anticancer therapeutics, which may result in cancer recurrence and patient mortality22. Thus, our research showing that EV206 has strong antitumor properties in NSCLC cells resistant to anticancer drugs supports the idea that EV206 could be useful as an effective anticancer drug in both therapy-naïve and therapy-resistant cells. The effects of EV206 on NSCLC cells and their subpopulations with acquired resistance to chemotherapy or EGFR TKI appear to be similar. These results are in line with previous reports, in which cancer cells that are naïve and those that acquired resistance to chemotherapy or molecular targeted therapy showed a similar degree of decrease in viability and induction of apoptosis in response to Hsp70 inhibitors15,23,24,25. Importantly, intraperitoneal treatment with EV206 had a substantial antitumor effect in vivo while causing minimal toxic effects. Collectively, these results imply the likelihood of EV206 as a potential hit or lead compound for developing efficacious anticancer agents with limited toxicity. In light of our previous research showing the essential role of Hsp70 in maintaining CSC populations in NSCLC and the interaction of evodiamine with the Hsp70 N-terminal domain8, the potent inhibitory effect of EV206 against NSCLC cells, including those that have acquired resistance to anticancer therapy, can be attributed to its Hsp70 inhibitory activity. Indeed, the DARTS assay (Fig. 6c) and fluorescence-based equilibrium binding assay (Fig. 6d) showed efficient binding of EV206 to the Hsp70 N-terminal domain. Therefore, it is likely that allyl substitution at the N14 position of evodiamine could potentiate the interaction of the drug with the Hsp70 nucleotide-binding residues, resulting in the anticancer effects of EV206.

Additional studies are needed to further develop EV206-based anti-cancer agents. Although EV206 inhibits Hsp70 activity by binding to the N-terminal region of Hsp70, further biochemical research is necessary to elucidate the detailed mechanism by which EV206 exerts its effects. Studies to evaluate the anticancer activity of EV206 using therapeutically relevant animal models and via different routes of administration are also necessary to validate the potential clinical utility of EV206. Additional investigations are necessary to achieve maximum therapeutic effectiveness while minimizing the adverse effects and toxicity. These investigations should encompass the development of pharmaceutical formulations that enhance physicochemical properties as well as the assessment of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics. In addition, since the nonselective effects on normal stem cells reduce the therapeutic effectiveness of anti-CSC agents22, the inhibitory effect of EV206 on normal stem cells needs to be tested.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that the evodiamine derivative EV206 is more effective than evodiamine in disturbing the HSP system. EV206 causes instability of Hsp70 and its client protein by binding directly to the Hsp70 N-terminal domain, thereby exerting considerable activity in the suppression of cell viability and formation of colonies and spheres in NSCLC cells, including those harboring resistance to anticancer therapeutics, by triggering apoptosis. Moreover, EV206 substantially blocked tumor growth with minimal toxicity. These data highlight the potential of EV206 as an anticancer drug targeting Hsp70, with broad applications in primary and secondary treatment options. Additional investigation is necessary to verify the therapeutic value of EV206 using various advanced preclinical and clinical models.

Methods

Reagents and cell culture

Detailed information on the reagents and cell lines utilized in the present study is listed in Supplementary Table 1 and in our previous report8,15. Detailed procedures for cell culture have been described in our previous literature15. Unless otherwise specified, chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Cells were cultured in the following media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (1× antibiotic-antimycotic solution): DMEM for NCTC 1469 and RPE; modified HITES15for MLE12; RPMI 1640 for A549, H1299, H460, H226B, PC9, and those carrying resistance to anticancer drugs. Cells acquiring resistance to anticancer drugs (H1299/CsR: cisplatin; H1299/PmR: pemetrexed; H460/PcR: paclitaxel, H226B/PcR: paclitaxel; PC9/ER: erlotinib) were generated by exposure to these drugs for more than six months with gradually increasing concentrations, as mentioned earlier8. Human cancer cell lines were validated using an AmplFLSTR identifier polymerase chain reaction (PCR) Amplification Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA, USA; cat. No. 4322288). Cells that were maintained for less than three months after being received or recovered and were verified to be free of mycoplasma were utilized in this study.

Synthesis of evodiamine derivatives

The procedures for the synthesis and characterization of evodiamine derivatives are described in detail in the Supplementary Materials. In addition, the supplementary materials contain1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectra of evodiamine derivatives.

Investigation of the impact of EV206 on cell viability, colony formation, and sphere formation

Our previous reports provided detailed descriptions of the methods used to assess the impact of EV206 on cell viability, colony formation in culture plates or soft agar, and sphere formation8,15.

To assess the impact on cell viability, cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 103cells/well. After treatment with the drugs for 48 h, the impact on cell viability was analyzed using MTT and crystal violet assays, following the methodology outlined in our previous study8. The GraphPad Prism software (ver. 10; GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) was used to determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of the drugs that were tested. We used non-linear regression analysis to determine IC50 values. When necessary, an extrapolation method was used to estimate the IC50 values.

To assess the effect on colony formation, cells were cultured in a 12-well culture plate (for colony formation under attached conditions) or embedded in 0.4% soft agar in a 12- or 24-well culture plate (for colony formation under detached conditions) for a period of 2–3 weeks. The generated colonies were stained using 0.025% crystal violet or MTT solution. They were then manually counted to quantify anchorage-dependent colony formation, photographed, and counted using ImageJ software (ver. 1.54 g, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MA, USA) to quantitatively assess anchorage-independent colony formation.

To assess the effect on sphere formation, viable cells were cultivated on a culture plate (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) designed to minimize attachment. The number of viable cells was determined using a trypan blue dye exclusion assay. The cells were grown without serum supplementation, but with additional sphere-enrichment supplements, including growth factors (20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor [EGF] and 20 ng/mL fibroblast growth factor [FGF]) and B-27 supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) diluted in DMEM/F12 media under unattached culture conditions using ultra-low attached multi-well plates (Corning). After culturing the spheroids for a period–2–3 weeks, images of the spheres were captured and analyzed using ImageJ software.

Flow cytometry

NSCLC cells underwent a 48-hour treatment with EV206. Flow cytometry-based assays to assess the apoptotic cell population and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity were performed using a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), as described in our previously published report8. To assess the apoptotic cell population, EV206-treated cells were fixed with 100% methanol and stained with propidium iodide (PI, 50 µg/mL) in the presence of RNase A (50 µg/mL), and changes in the distribution of cells in each phase of the cell cycle were analyzed by flow cytometry. The sub-G1 phase was determined by manual gating using the CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). We determined the ALDH activity of vehicle- and EV206-treated cells using an AldeRed ALDH detection assay kit (cat No. SCR150, Merck, KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) according to the procures provided by the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blot analysis and real-time PCR

Western blot analysis and real-time PCR were performed as described in our recent publication8,15. The cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of EV206 for 48 h. Total cell lysates obtained using modified RIPA lysis buffer were used for western blot analysis. Densitometry was performed using the ImageJ software to quantify the blots. RNA was isolated from NSCLC spheres treated with the vehicle (DMSO) or EV206 (0.1 µM). The PCR primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Drug affinity responsive target stability (DARTS) assay

Purification of the recombinant Hsp70 protein and DARTS assay were carried out as described previous reports8,26. Hsp70 proteins (35 µg) were pre-incubated for 30 min at 4 °C with 0, 1, or 10 µM EV206 (final concentration, 1%). After treatment with proteinase K at a ratio of 1:100 (proteinase K: Hsp70 protein) for 15 min at room temperature, 5× SDS-PAGE sample buffer was added to the tubes, and the mixtures were boiled at 95 °C for five minutes. Following 8% SDS-PAGE, lysates were visualized using Coomassie brilliant blue staining.

Fluorescence-based ligand binding assay

To assess the binding affinities of EV206 to Hsp70 N- and C-terminal domains, a fluorescence-based ligand-binding assay was conducted18. Prior to measuring the fluorescence emission, the full-length and truncated forms (N-terminal and C-terminal domains) of Hsp70 were equilibrated with different concentrations of EV206. Titration experiments were performed at a temperature of 20 °C using a Jasco FP 6500 spectrofluorometer (Easton, MD, USA). The ligand stock solutions were titrated into a protein sample dissolved in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, and 2 mM KH2PO4). Protein samples were excited at a wavelength of 280 nm, and the subsequent decrease in fluorescence emission resulting from ligand binding was measured at 305 nm. This measurement was then used to determine the relationship between the ligand concentration and fluorescence emission. The titration data were analyzed using a hyperbolic binding equation to determine the Kd values.

Tumor xenograft experiment

The tumor xenograft experiment was conducted following protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Seoul National University (approval No. 201026-5-1). Animal care and procedures for animal experiments were carried out according to the guidelines for ethical animal experiments from Seoul National University and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th edition), published by the National Research Council of the National Academics. In addition, the animal experiments in this study were reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines. The mice were provided with standard chow and water and housed in a controlled environment with regulated temperature, humidity, and a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle. H460 cells (5 × 106 cells per spot) were mixed with Matrigel at a 1:1 ratio and injected into the right flanks of male and female Balb/c nude mice (6-week-old age). The nude mice were purchased from Nara Biotech (Seoul, Republic of Korea). Once the tumor volume reached 50–150 mm3, the mice were randomly assigned to control (vehicle) and EV206-treated (EV206) groups. We empirically determined the sample size of the animal experiment, rather than using a statistical method. The mice were then administered either a vehicle (25% DMSO and 35% PEG400 diluted in 0.9% NaCl solution) or EV206 (10 mg/kg) intraperitoneally every other day for 16 days. Tumor growth was measured using a caliper to assess the tumor’s short and long diameters, and the tumor volume was computed using the following formula: tumor volume (mm3) = (small diameter)2×(large diameter) × 0.5, as described in our publication8. The tumor growth was monitored in a blinded manner. After completing drug treatment, the mice were euthanized by inhalation of excessive doses of isoflurane. All animals were used for experiments and data analysis. Statistical analysis of the difference in tumor growth between the vehicle and EV206 groups was performed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Statistics

The results in the table and bar graphs are shown as the mean ± SD. Data acquired from in vitro experiments are representative of results from at least two repeated experiments. The GraphPad Prism software (ver. 10) was used for statistical analysis of the results. The statistical significance of the differences was determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test for comparison of two groups or a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for comparison of more than three groups. We conducted the F-test (for two groups) or the Brown-Forsythe test (for more than three groups) to verify the equal variance of the groups. We also validated the normality of the distribution of the data using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Statistical significance was set p values < 0.05.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.71, 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2021).

Bareschino, M. A. et al. Treatment of advanced non small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Dis.3, 122–133. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2010.12.08 (2011).

Cheng, Y., Zhang, T. & Xu, Q. Therapeutic advances in non-small cell lung cancer: focus on clinical development of targeted therapy and immunotherapy. MedComm (2020). 2, 692–729. https://doi.org/10.1002/mco2.105 (2021).

Howlader, N. et al. The effect of advances in lung-Cancer treatment on Population Mortality. N Engl. J. Med.383, 640–649. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1916623 (2020).

Maeda, H. & Khatami, M. Analyses of repeated failures in cancer therapy for solid tumors: poor tumor-selective drug delivery, low therapeutic efficacy and unsustainable costs. Clin. Transl Med.7, 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40169-018-0185-6 (2018).

Newman, D. J. & Cragg, G. M. Natural products as sources of New drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod.83, 770–803. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b01285 (2020).

Sun, Q., Xie, L., Song, J., Li, X. & Evodiamine A review of its pharmacology, toxicity, pharmacokinetics and preparation researches. J. Ethnopharmacol.262, 113164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2020.113164 (2020).

Hyun, S. Y. et al. Evodiamine inhibits both stem cell and non-stem-cell populations in human cancer cells by targeting heat shock protein 70. Theranostics 11, 2932–2952 (2021). https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.49876

Sha, G. et al. The multifunction of HSP70 in cancer: Guardian or traitor to the survival of tumor cells and the next potential therapeutic target. Int. Immunopharmacol.122, 110492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110492 (2023).

Chen, T. & Cao, X. Stress for maintaining memory: HSP70 as a mobile messenger for innate and adaptive immunity. Eur. J. Immunol.40, 1541–1544. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.201040616 (2010).

Albakova, Z., Armeev, G. A., Kanevskiy, L. M., Kovalenko, E. I. & Sapozhnikov, A. M. HSP70 Multi-functionality in Cancer. Cells. 9https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9030587 (2020).

Sherman, M. Y. & Gabai, V. L. Hsp70 in cancer: back to the future. Oncogene. 34, 4153–4161. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2014.349 (2015).

Dong, G. et al. New tricks for an old natural product: discovery of highly potent evodiamine derivatives as novel antitumor agents by systemic structure-activity relationship analysis and biological evaluations. J. Med. Chem.55, 7593–7613. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm300605m (2012).

Wang, S. et al. Scaffold Diversity inspired by the natural product evodiamine: Discovery of highly potent and Multitargeting Antitumor agents. J. Med. Chem.58, 6678–6696. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00910 (2015).

Min, H. Y. et al. An A-ring substituted evodiamine derivative with potent anticancer activity against human non-small cell lung cancer cells by targeting heat shock protein 70. Biochem. Pharmacol.211, 115507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2023.115507 (2023).

Toledo-Guzman, M. E., Hernandez, M. I., Gomez-Gallegos, A. A. & Ortiz-Sanchez, E. ALDH as a stem cell marker in solid tumors. Curr. Stem Cell. Res. Ther.14, 375–388. https://doi.org/10.2174/1574888X13666180810120012 (2019).

Paterson, C. et al. Cell populations expressing stemness-Associated markers in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Life (Basel). 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11101106 (2021).

Takahashi, M., Altschmied, L. & Hillen, W. Kinetic and equilibrium characterization of the Tet repressor-tetracycline complex by fluorescence measurements. Evidence for divalent metal ion requirement and energy transfer. J. Mol. Biol.187, 341–348 (1986).

Calderwood, S. K. & Gong, J. Heat shock proteins promote Cancer: it’s a Protection Racket. Trends Biochem. Sci.41, 311–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2016.01.003 (2016).

Dong, G. et al. Selection of evodiamine as a novel topoisomerase I inhibitor by structure-based virtual screening and hit optimization of evodiamine derivatives as antitumor agents. J. Med. Chem.53, 7521–7531. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm100387d (2010).

Hao, X. et al. Design, synthesis and bioactivity evaluation of novel N-phenyl-substituted evodiamine derivatives as potent anti-tumor agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem.55, 116595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2021.116595 (2021).

Rezayatmand, H., Razmkhah, M. & Razeghian-Jahromi, I. Drug resistance in cancer therapy: the Pandora’s Box of cancer stem cells. Stem Cell. Res. Ther.13, 181. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-022-02856-6 (2022).

Song, T. et al. Small-molecule inhibitor targeting the Hsp70-Bim protein-protein interaction in CML cells overcomes BCR-ABL-independent TKI resistance. Leukemia. 35, 2862–2874. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-021-01283-5 (2021).

Hu, C. et al. Targeting chaperon protein HSP70 as a novel therapeutic strategy for FLT3-ITD-positive acute myeloid leukemia. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther.6, 334. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-021-00672-7 (2021).

Koren, J. 3 et al. Rhodacyanine derivative selectively targets cancer cells and overcomes tamoxifen resistance. PLoS One. 7, e35566. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035566 (2012).

Lomenick, B. et al. Target identification using drug affinity responsive target stability (DARTS). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 106, 21984–21989. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0910040106 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) of the Republic of Korea (No. NRF-2016R1A3B1908631) and KRIBB Research Initiative Program (No. KGM5192423).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HYM performed in vitro and in vivo experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. YL, JH, and SH designed and synthesized evodiamine derivatives. HK and JK performed in vitro experiments. JP, SK, and JL performed a fluorescence-based ligand binding assay. HYL conceived, designed, and supervised the study, wrote the manuscript, and acquired funding.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest disclosure statement

There are no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Min, HY., Lim, Y., Kwon, H. et al. Development of a novel N14-substituted antitumor evodiamine derivative with inhibiting heat shock protein 70 in non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep 14, 25436 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74926-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74926-z