Abstract

This trial examined the effectiveness of the popliteal plexus block (PPB) and tibial nerve block (TNB) for early rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty (TKA). We allocated 136 participants to receive PPB or TNB with 0.25% levobupivacaine 10 mL in a randomized, double-masked manner. The primary outcome was achieving rehabilitation goals with a non-inferiority 9-hour margin, including adequate pain relief, knee flexion angles over 90 degrees, and enabling ambulatory rehabilitation. The time to reach rehabilitation goals showed non-inferiority with 49.7 ± 10.5 h for TNB and 47.4 ± 9.7 h for PPB, whose mean difference (PPB - TNB) was − 2.3 h (95% CI -5.8 to 1.2 h; P < 0.001). PPB showed higher dorsal and plantar percentage of maximum voluntary isometric contraction (dorsal, PPB 87.7% ± 11.4% vs. TNB 74.0% ± 16.5%: P < 0.001; plantar, PPB 90.9% ± 10.3% vs. TNB 72.1% ± 16.0%; P < 0.001) at six hours after nerve block. No significant differences between the two groups emerged in pain scores, knee range of motion, additional analgesic requirements, success in the straight leg raise, and adverse events. PPB exhibited non-inferiority to TNB in achieving postoperative rehabilitation goals and had superiority in preserving foot motor strength after TKA. (200)

Similar content being viewed by others

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a surgical procedure that effectively alleviates pain and enhances mobility for individuals suffering from knee joint disorders. It is widely known that a combination of regional anesthesia, including peripheral nerve blocks (PNB), and multimodal analgesic techniques is effective in obtaining postoperative analgesia for TKA1. Periarticular injection (PAI) and selective tibial nerve block have been reported to be useful in obtaining postoperative analgesia in the posterior knee joint while preserving ankle joint motion2. In addition, the interspace between the popliteal artery and the posterior capsule of the knee block (IPACK) has also been shown to provide good quality analgesia when combined with adductor canal block (ACB) or femoral triangular block (FTB) while preserving lower leg motor function3.

Although previous studies have shown that TNB was less likely to cause the common peroneal nerve block than SNB4, thus preserving postoperative dorsal foot motion, it is worth noting that TNB may affect ankle mobility, depending on the extent of local anesthetic spread5. Additionally, a case report observed IPACK causing spread to the terminal branch of the sciatic nerve, leading to a motor deficiency of dorsal foot motion known as “foot drop”6.

Popliteal plexus block (PPB) is a procedure where local anesthetics are injected into the adductor canal, positioned about 1–2 cm above the adductor hiatus. The injected solutions then disperse distally to the adductor hiatus and towards the popliteal fossa. To mitigate the risk of SNB, limiting the volume of local anesthetic to 10–15 mL is recommended, allowing for the blockage of the genicular nerve, posterior obturator, and tibial nerves7,8,9. Recent research showed that PPB with FTB resulted in a significant reduction in postoperative opioid consumption after TKA compared with FTB or ACB alone10.

This study aims to investigate the impact of PPB on the postoperative pain management and rehabilitation progress following TKA combined with a single-shot ACB. We hypothesize that PPB will demonstrate non-inferiority to TNB in achieving rehabilitation objectives during the early postoperative period. Our secondary outcomes of interest include postoperative pain scores, ankle mobility gauged through muscle strength assessment, knee range of motion (ROM), additional analgesics, and potential adverse events.

Results

This study included 136 patients (Fig. 1), of whom 132 completed the protocols; four were excluded due to protocol violations. Patient demographics were not significantly different (Table 1).

Analysis of the primary outcome showed a difference in the mean time to reach rehabilitation goals between the TNB (49.7 ± 10.5 h) and PPB (47.4 ± 9.7 h) groups of -2.3 h (95% CI -5.8 to 1.2 h; P < 0.001) (Table 2). The upper CI of the difference was lower than the non-inferiority margin (Fig. 2).

Non-inferiority plot showing the observed difference between popliteal plexus block (PPB) and tibial nerve block (TNB) in the achievement of rehabilitation goals (Numeric Rating Pain Scale ≤ 4 at rest, 30-meter walk with a walker, and ability to perform 90° knee flexion). The dashed line indicates the non-inferiority margin (Δ). The horizontal bars indicate the 95% CI difference between the PPB and TNB groups. P < 0.05 was taken to indicate statistical significance.

No significant differences in NRS scores at rest or during knee flexion were observed between the groups at any point (Fig. 3). No statistical differences were found in knee ROM, ability to perform the SLR test at any time point, additional analgesic requirements, and incidence of postoperative adverse events, including postoperative nausea and vomiting, falls, and pruritus (Table 2).

Comparison of the numerical rating scale (NRS) (0–10, where 0 = no pain and 10 = the worst imaginable pain) at rest and during knee flexion rehabilitation over the first 72 h after total knee arthroplasty. Data are expressed as median (horizontal bar) with 25th–75th (box), range (whiskers), and outliers (dots). There was no significant difference at 0.05, representing overall comparison across the tibial and popliteal plexus block groups: TNB, tibial nerve block; PPB, popliteal plexus block.

The dorsal and plantar %MVIC 6 h after PNB were significantly higher in the PPB group (dorsal, PPB 87.7% ± 11.4% vs. TNB 74.0% ± 16.5%; difference, 13.6% [8.8-18.5%]; P < 0.001; plantar, PPB 90.9% ± 10.3% vs. TNB 72.1% ± 16.0%; difference, 18.9% [14.2-23.5%]; P < 0.001, Table 2). However, both %MVIC 24 h after PNB were insignificant between the two groups.

Discussion

This trial demonstrated that PPB showed non-inferiority to TNB in achieving rehabilitation goals, including knee flexion, ambulation, and pain control with oral analgesics after TKA. Regarding secondary outcomes, PPB maintained statistically higher levels of dorsi flexion and plantar flexion muscle strength six hours after surgery. When examining postoperative NRS pain scores, frequency of analgesic use, knee ROM, and adverse effects, the results emphasized PPB as a viable alternative to TNB for post-TKA pain management.

The actual value and 95% CI, assuming non-inferiority in postoperative rehabilitation goals, indicates that at least PPB did not increase the time to meet the discharge criteria beyond the standard 9 h compared to TNB, and 95% CI for the difference between the two groups ranges from − 5.8 h to 1.2 h, showed no clinically significant impact on outcome. The ability of PPB to achieve rehabilitation outcomes without lagging behind TNB has several advantages, including prompt postoperative gait training, appropriate analgesia with oral medications, and knee flexion rehabilitation. These factors help to reduce postoperative disability, resulting in early recovery, discharge, and lower medical costs11. As demonstrated in this study, PPB excels in maintaining dorsi flexion and plantar flexion.

Additionally, PPB reduces the risk of the common peroneal nerve block compared to TNB, potentially impacting the immediate postoperative demonstration of the absence of surgical common peroneal nerve injury. PPB can be performed in the same leg position as ACB, making it more accessible than TNB, which requires a change in leg position. Furthermore, the comparable results regarding the ability to perform SLR suggest that the combination of proximal ACB with TNB or PPB did not affect quadriceps motor weakness in the early period after TKA. The absence of differences in postoperative adverse effects, including nausea, vomiting, falls, and pruritus, suggests that our study setting did not interfere with rehabilitation progress immediately after TKA.

Anatomical evidence from a cadaveric study has clarified the neural branches innervating the posterior knee capsule, including the posterior division of the obturator and tibial nerves, articular branches of the common peroneal nerve, and the sciatic nerve, which form the intricate popliteal plexus12. This anatomical understanding supports the augmentation of femoral triangle block or ACB combined with obturator or sciatic nerve block to improve postoperative pain control after TKA13,14. In addition, TNB has emerged as a viable pain management technique that provides adequate blockade of the posterior division of the tibial nerve while avoiding ankle motor impairment4; however, the recent trial showed TNB had no superior analgesic efficacy compared to the local infiltration analgesia in the posterior knee capsule15.

We consider that the advent of the IPACK technique highlights its efficacy in targeting the terminal branches of the sciatic and posterior obturator nerves, which innervate the posterior knee capsule. A cadaveric study showed that both the proximal and distal IPACK injection methods resulted in comparable dye distribution within the popliteal region and extensive staining of the articular branches supplying the posterior capsule16. In contrast, PPB extends the dye from the adductor canal into the posterior knee, encompassing the popliteal area through the adductor hiatus8,17. This spread depends on the volume of local anesthetic administered9. PPB delivers local anesthetic to a more superficial area around the adductor canal and femoral artery than IPACK. Our study suggests that this indirect distribution effectively provides adequate analgesia for post-TKA, as evidenced by postoperative NRS scores.

A previous study compared the administration of 0.25% levobupivacaine (20 ml) in TNB, proximal IPACK, and distal IPACK. The results demonstrated that the two IPACK procedures were significantly less likely to induce motor weakness than TNB18. The present study showed that administering a reduced quantity of levobupivacaine in either PPB or TNB was an efficacious method for providing postoperative pain relief while simultaneously preserving the muscle strength of plantar and dorsi flexion at the six-hour postoperative mark. Notably, our study employed a lower dosage than that utilized in previously published PAI or IPACK protocols19,20. These results provide a rationale for selecting PPB in institutions prioritizing early gait training within 24 h of the surgery. However, we should notice that this difference became practically insignificant 24 h after surgery. A previous clinical finding indicated that the injection of local anesthetic and contrast solutions into the adductor canal distributes to the sciatic nerve territory via the adductor hiatus without resulting in foot motor weakness21. Another cadaveric study demonstrated a significant proximal spread of local anesthetic after TNB, which may result in unwanted motor blocks of the peroneal nerve5. The results of our trial confirm those of previous studies indicating that TNB may induce motor weakness in dorsal foot movement due to the common peroneal nerve block. While muscle sparing is advantageous in fast-track rehabilitation programs, especially when early gait training is initiated after surgery, avoiding excessive local anesthetic administration is critical to prevent inadvertent spread to the sciatic nerve. Therefore, selecting a nerve block technique such as PPB that does not significantly reduce foot motor function is beneficial.

Effective pain management is of paramount importance for the active engagement of patients in the early postoperative rehabilitation process22. Some institutions have implemented an accelerated gait rehabilitation program for patients discharged on postoperative day (POD) 0 or POD 1, intending to reduce hospital stay and healthcare costs23,24. However, the surgical team hesitated to perform gait training on POD 0 due to the participants’ advanced age and declining physical abilities. Moreover, the surgical team hypothesized that initiating gait training on POD 0 would not markedly reduce the duration of hospitalization compared to commencing on the morning of POD 1, based on the findings of a prior study22. Variations in postoperative management and rehabilitation strategies have resulted in discrepancies in length of stay and rehabilitation objectives across institutions25,26.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study, particularly concerning the relatively large non-inferiority margin for the primary outcome. The margin may not have fully reflected the reality in other institutions prioritizing early rehabilitation. The larger margin for rehabilitation goals was accepted because our institution did not have a predisposition for postoperative management of gait training on the same day after surgery. Additionally, early discharge within one day after surgery did not contribute to our hospital revenue in terms of national insurance reimbursement. Furthermore, the start time of postoperative rehabilitation interventions was set at a later point in the day, with a larger margin, due to the assumption that the difference of up to 9 h between early morning and afternoon interventions would not contribute to hospital revenue. Nevertheless, evidence from other countries indicates that a narrower margin may be more appropriate. In settings with intensive rehabilitation, increasing the sample size may enhance the statistical power of the study. Earlier rehabilitation and discharge could diminish the healthcare resource consumption associated with pain management therapy and potentially augment hospital revenue while reducing national health insurance costs27.

Our view is that the achievement of the primary endpoint is an indicator of the success of the surgery. It should be noted, however, that each participant’s knee mobile ability and walking ability may vary. In addition, the mere administration of regional anesthesia to relieve postoperative pain does not necessarily guarantee a positive surgical outcome. Therefore, the primary outcome was limited to measuring participants’ ability following TKA for early discharge, including pain, ambulation, and knee flexibility. Furthermore, at the trial outset, we did not regard IPACK as a procedure that could be meaningfully compared with PPB or TNB. Future studies should evaluate the postoperative analgesic and motor-sparing effects of IPACK versus PPB plus proximal ACB. In our study, we limited the volume of a local anesthetic to 10 ml for PPB or TNB based on a cadaver study that indicated the potential for spread from the proximal adductor canal to the posterior knee, which could affect outcomes17,28. Because the optimal dose of local anesthetic required to achieve analgesia of the posterior knee and knee capsule varies with patient background and surgical invasiveness, differences in motor function may be observed with increasing doses of local anesthetic.

Conclusions

The results confirmed that PPB had non-inferiority to TNB in accelerating the achievement of postoperative rehabilitation goals. In addition, PPB demonstrated superiority in preserving ankle strength in the early postoperative period.

Methods

Patients, blinding, and allocation

This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and data presentation followed the guidelines of the CONSORT statement. The Institutional Review Board of Daiyukai General Hospital approved the trial protocol (No. 2019-024, March 4, 2020), and all participating patients provided written informed consent. Before patient recruitment, the study was registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN000040054, registered on 04/April/ 2020, URL: https://center6.umin.ac.jp/cgi-open-bin/ctr_e/ctr_view.cgi?recptno=R000045668). Recruitment for the study took place between April 6, 2020, and June 23, 2021. Inclusion criteria included patients over 20 years of age, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) I-III classification, undergoing unilateral TKA for knee osteoarthritis. Exclusion criteria included unplanned implants or surgical procedures, concurrent bilateral TKA, revision TKA, allergy to study medications, chronic opioid use, neuromuscular deficits, infection, and contraindications to PNB.

Before surgery, participants were randomly assigned to receive either PPB or TNB using a computer-generated random number sequence with a block size of 4 and an allocation ratio of 1:1. Information regarding treatment group allocation was concealed in a sealed envelope. All surgeons, nurses, and physiotherapists were blinded to the allocation.

Regional anesthesia techniques

An experienced anesthesiologist performed preoperative nerve blocks in an operating room. An electrocardiogram, pulse oximetry, and blood pressure monitoring were also performed. Peripheral intravenous (IV) access was established, and intravenous midazolam (0.03–0.04 mg/kg) was administered before block procedures for blinding. PNB procedures were performed using a high-frequency linear ultrasound transducer (Logic E Premium, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL) and a 10-cm, 21-gauge PNB needle (Echoplex plus; Vygon, Paris, France).

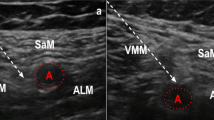

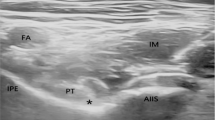

The ACB procedure targeted the proximal end of the adductor canal where the medial edges of the sartorius and adductor longus muscles intersect28. The needle was inserted perpendicular to the nerve at this level using an in-plane approach from a lateral-to-medial direction. The needle tip was positioned at the nerve structures, including the bifurcated saphenous nerve and the vastus medialis branch. We then administered 10 mL of levobupivacaine 0.25% around the nerve.

During the TNB procedure, the subject was placed supine with the hip and knee joints flexed (Fig. 4_A1). The ultrasound probe was positioned in the popliteal fossa, perpendicular to the femur, and moved slightly cephalad to locate the popliteal artery and nerve structures. The bifurcation of the sciatic nerve into the common peroneal and tibial nerves was visualized. The needle was then inserted from the lateral thigh using the in-plane technique. The needle tip was advanced into the medial aspect of the tibial nerve and approached tangentially4 (Fig. 4_A2). We then administered 10 mL of levobupivacaine 0.25% on the medial side of the tibial nerve.

Ultrasound-guided selective tibial nerve block (A1-2) and popliteal plexus block. (B1–2). Tibial nerve block: The subjects were supine with participants’ legs bent upwards to 90 degrees. (A1) We fitted the ultrasound transducer position in the short-axis view of the tibial nerve on the posterior thigh. We placed a block needle (cyan arrows) from the lateral side of the thigh to the medial side of the tibial nerve. (A2) Local anesthetics were injected around the tibial nerve component. Popliteal nerve block: The subjects were supine, with the knee slightly flexed. (B1) We positioned the ultrasound transducer in the short-axis view of the femoral artery, which entered the popliteal fossa. We pierced the nerve block needle (cyan arrows) into the vastus medialis muscle. The target of the needle tip was the posteromedial side of the femoral artery. (B2) Local anesthetics were injected between the sartorius and the adductor magnus muscle, spreading into the popliteal fossa’s direction. TN, Tibial nerve; CPN, common peroneal nerve; BFM, biceps femoris muscle; STM, semitendinous muscle; FA, femoral artery; SM, sartorius muscle; AMM, adductor magnus muscle; VMM, vastus medialis muscle; White asterisk, local anesthetics.

For the PPB procedure, the subject remained supine with the knee slightly flexed (Fig. 4_B1). The ultrasound probe was positioned at the same level as the ACB and moved downward along the femoral artery until the artery separated from the sartorius muscle at the distal end of the adductor canal, resulting in the adductor hiatus7. We identified the target site as the space between the vastus medialis and adductor magnus muscles, with slight posteromedial encroachment of the sartorius muscle. The needle was inserted through the vastus medialis muscle and positioned to approach the artery tangentially in the medial artery region (Fig. 4_B2). We then administered 10 mL of levobupivacaine 0.25% to allow for distribution between the artery and the adductor magnus muscle.

To maintain blinding, all subjects in each group who were sedated with midazolam were positioned in the lower extremity for TNB or PPB, performed the disinfection maneuver, and then received local anesthesia with lidocaine at the intended puncture site and held in this position for 1 min. However, the actual block needle insertion was not performed.

Perioperative management

All participants underwent general anesthesia with a supraglottic airway. Anesthesia was induced and maintained with air/oxygen, propofol, fentanyl, and intravenous dexamethasone (3.3 mg) as an antiemetic. The same surgical team performed TKA using a mini-mid parapatellar approach with a 12–15 cm midline skin incision and the same prosthetic implant (Fine CR, Teijin-Nakashima Medical, Okayama, Japan). After patella replacement, fixation was secured with bone cement, and a drainage tube was inserted. A tourniquet was applied with an inflation pressure of 300 mmHg. Before skin closure, surgeons only injected 10 mL of ropivacaine 0.75% (75 mg) into the surgical incision line.

After surgery, all participants received 1000 mg of paracetamol by intravenous injection one hour after surgery. Subsequently, they received paracetamol 500 mg every eight hours and celecoxib 200 mg every 12 h. If they had a patient-reported numeric rating scale (NRS) of ≥ 5 at rest, they received tramadol 25 mg. For breakthrough pain, diclofenac 50 mg was administered by suppository or pentazocine 15 mg by intramuscular injection. The drainage tube was removed on the morning of the first postoperative day.

Study results and analysis

The primary endpoint was the time to rehabilitation goal, defined as achieving an NRS ≤ 4 at rest with scheduled analgesics, walking 30 m with a walker, and demonstrating the voluntary performance of 90° knee flexion11,29. Secondary endpoints included the following: (1) NRS at rest and during knee flexion rehabilitation at 1, 6, 10, and 24 h postoperatively, (2) active knee range of motion (ROM) on postoperative days 1–3, (3) additional analgesic requirements for 72 h postoperatively, (4) straight leg raise (SLR) success at 1, 6, 24, and 72 h postoperatively, defined as the ability to raise the operative limb 10 cm above the waist for at least 10 s in the supine position, (5) frequency of postoperative adverse events, including postoperative nausea and vomiting, falls, pruritus, and (6) assessment of maximum voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC) of foot movement.

Nurses recorded NRS scores and adverse events every two hours from 6:00 am to 10:00 pm. Physical therapists assessed patients at least twice daily (morning and afternoon), SLR test feasibility, knee ROM, and gait training, specifically the patient’s ability to walk over 30 m.

Ankle plantar and dorsi flexion strengths were measured using a handheld dynamometer (µ-TAS F1; Anima, Tokyo, Japan) as the MVIC29. During the measurement, the participants lay supine with the leg immobilized, and the evaluator applied the dynamometer to the plantar or dorsal foot. The evaluator instructed the participants to exert maximum effort for a 5-second contraction followed by relaxation, with the procedure repeated twice. The average of these measurements was recorded the day before surgery and 6 and 24 h after surgery following nerve blocks. These values were expressed as a percentage of preoperative MVIC (%MVIC)30.

Statistics and sample size calculation

To assess the non-inferiority of PPB compared to TNB, we conducted an unpublished pilot study with ten participants in each group. The mean time to achieve rehabilitation goals was 64.1 ± 14.6 h for TNB and 60.2 ± 15.5 h for PPB in the ten participants. Previous studies in TKA comparing continuous FNB with placebo showed a median difference of 15 h in the time to meet discharge criteria, including pain relief, additional opioids, and ambulation11. Considering the acceptable non-inferiority margin that should be established relative to placebo31, we expected the subjective difference to be approximately 50% of the previously mentioned results from a placebo-controlled trial. The standard deviation (SD) was adopted from our preliminary results; thus, each group should consist of 63 patients, with a power of 0.9, a one-sided α of 0.025, a non-inferiority margin of 9 h, and an SD of 15.5 h. We enrolled 136 patients, accounting for potential dropouts.

A one-tailed t-test with a significance level of 2.5% was used to test the non-inferiority hypothesis. Categorical data were presented as percentages (%) and analyzed using the chi-squared test with a calculation of the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the odds ratio. Non-normally distributed continuous and nonparametric data were expressed as median and range, and we used the Mann-Whitney U test, including a 95% CI for the median difference when possible. For normally distributed data, we reported the mean and standard deviation, along with a 95% CI, and analyzed them using Student’s t-test. A two-tailed P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant, except for the non-inferiority hypothesis. All statistical analyses were performed with R version 4.1.6 (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. In addition, sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trial Registry (UMIN-CTR) with the primary accession code UMIN000040054. (need UMIN ID)UMIN CTR: https://center6.umin.ac.jp/cgi-open-bin/ctr_e/ctr_view.cgi? recptno=R000045668.

Abbreviations

- TKA:

-

Total knee arthroplasty

- PAI:

-

Periarticular injection

- PNB:

-

Peripheral nerve block

- FNB:

-

Femoral nerve block

- FTB:

-

Femoral triangle block

- ACB:

-

Adductor canal block

- SNB:

-

Sciatic nerve block

- TNB:

-

Tibial nerve block

- ONB:

-

Obturator nerve block

- IPACK:

-

The interspace between the popliteal artery and posterior capsule of the knee block

- PPB:

-

Popliteal plexus block

- ROM:

-

Range of motion

- CONSORT:

-

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- UMIN:

-

University Hospital Medical Information Network

- ASA:

-

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- NRS:

-

Numeric Rating Scale for pain

- SLR:

-

Straight leg raise

- MVIC:

-

Maximum voluntary isometric contraction

- %MVIC:

-

Percentage of preoperative MVIC

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- POD:

-

Postoperative day

References

Memtsoudis, S. G. et al. Peripheral nerve block anesthesia/analgesia for patientsundergoing primary hip and knee arthroplasty: recommendations from theInternational Consensus on Anesthesia-Related Outcomes after Surgery (ICAROS)group based on a systematic review and meta-analysis of current literature. RegAnesth Pain Med. 46, 971–985. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2021-102750 (2021).

Paulou, F. et al. Analgesic efficacy of selective tibial nerve block versus partial local infiltration analgesia for posterior pain after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled, triple-blinded trial. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 42, 101223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accpm.2023.101223 (2023).

Xue, X., Lv, X., Ma, X., Zhou, Y. & Yu, N. Postoperative pain relief after total knee arthroplasty: A Bayesian network meta-analysis and systematic review of analgesic strategies based on nerve blocks. J Clin Anesth 96, 111490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2024.111490 (2024).

Sinha, S. K. et al. Femoral nerve block with selective tibial nerve block provides effective analgesia without foot drop after total knee arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized, observer-blinded study. Anesth Analg. 115, 202–206. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182536193 (2012).

Silverman, E. R. et al. The anatomic relationship of the tibial nerve to the common peroneal nerve in the popliteal fossa: implications for selective tibial nerve block in total knee arthroplasty. Pain Res Manag. 2017, 7250181. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/7250181 (2017).

Sreckovic, S. D., Tulic, G. D. Z., Jokanovic, M. N., Dabetic, U. D. J. & Kadija, M. V. Delayed foot drop after a combination of the adductor canal block and IPACK block following total knee arthroplasty. J Clin Anesth. 73, 110363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2021.110363 (2021).

Runge, C. et al. The analgesic effect of a popliteal plexus blockade after total knee arthroplasty: a feasibility study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 62, 1127–1132. https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.13145 (2018).

Runge, C., Moriggl, B., Børglum, J. & Bendtsen, T. F. The spread of ultrasound-guided injectate from the adductor canal to the genicular branch of the posterior obturator nerve and the popliteal plexus: a cadaveric study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 42, 725–730. https://doi.org/10.1097/AAP.0000000000000675 (2017).

Andersen, H. L., Andersen, S. L. & Tranum-Jensen, J. The spread of injectate during saphenous nerve block at the adductor canal: a cadaver study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 59, 238–245. https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.12451 (2015).

Sørensen J.K., Grevstad U., Jaeger P., Nikolajsen L. & Runge C. Effects of popliteal plexus block after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized clinical trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. Epub ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2024-105747 (2024).

Ilfeld, B. M. et al. A multicenter, randomized, triple-masked, placebo-controlled trial of the effect of ambulatory continuous femoral nerve blocks on discharge-readiness following total knee arthroplasty in patients on general orthopaedic wards. Pain. 150, 477–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.05.028 (2010).

Tran, J., Peng, P. W. H., Gofeld, M., Chan, V. & Agur, A. M. R. Anatomical study of the innervation of posterior knee joint capsule: implication for image-guided intervention. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 44, 234–238. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2018-000015 (2019).

Abdallah, F. W. et al. The analgesic effects of proximal, distal, or no sciatic nerve block on posterior knee pain after total knee arthroplasty: a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial. Anesthesiology. 121, 1302–1310. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000000406 (2014).

Runge, C. et al. The analgesic effect of obturator nerve block added to a femoral triangle block after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 41, 445–451. https://doi.org/10.1097/AAP.0000000000000406 (2016).

Paulou, F. et al. Analgesic efficacy of selective tibial nerve block versus partial local infiltration analgesia for posterior pain after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled, triple-blinded trial. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 42, 101223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accpm.2023.101223 (2023).

Tran, J. et al. Evaluation of the iPACK block injectate spread: a cadaveric study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 44, 689–694. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2018-100355 (2019).

Sonawane, K., Dixit, H., Mistry, T., Gurumoorthi, P. & Balavenkatasubramanian, J. Anatomical and technical considerations of the hi-pac (hi-volume proximal adductor canal) block: a novel motor-sparing regional analgesia technique for below-knee surgeries. Cureus. 14, e21953. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.21953 (2022).

Kampitak, W., Tanavalee, A., Ngarmukos, S. & Tantavisut, S. Motor-sparing effect of iPACK (interspace between the popliteal artery and capsule of the posterior knee) block versus tibial nerve block after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 45, 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2019-100895 (2020).

Albrecht, E., Guyen, O., Jacot-Guillarmod, A. & Kirkham, K. R. The analgesic efficacy of local infiltration analgesia vs femoral nerve block after total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 116, 597–609. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aew099 (2016).

Albrecht, E., Wegrzyn, J., Dabetic, A. & El-Boghdadly, K. The analgesic efficacy of iPACK after knee surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. J Clin Anesth. 72, 110305 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2021.110305 (2021).

Gautier, P. E. et al. Distribution of injectate and sensory-motor blockade after adductor canal block. Anesth Analg. 122, 279–282. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000001025 (2016).

Bohl, D. D. et al. Physical therapy on postoperative day zero following total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial of 394 patients. J Arthroplasty. 34, S173-177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2019.02.010 (2019).

Rana, A. J. & Bozic, K. J. Bundled payments in orthopaedics. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 473, 422–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-014-3520-2 (2015).

Molloy, I. B., Martin, B. I., Moschetti, W. E. & Jevsevar, D. S. Effects of the length of stay on the cost of total knee and total hip arthroplasty from 2002 to 2013. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 99, 402–407. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.16.00019 (2017).

Jenny, J. Y. et al. Fast-track procedures after primary total knee arthroplasty reduce hospital stay by unselected patients: a prospective national multi-centre study. Int Orthop. 45, 133–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-020-04680-0 (2021).

Brüggenjürgen, B., Muehlendyck, C., Gador, L. V. & Katzer, A. Length of stay after introduction of a new total knee arthroplasty (TKA)-results of a German retrospective database analysis. Med Devices (Auckl). 12, 245–251. https://doi.org/10.2147/MDER.S191529 (2019).

Tilleul, P. et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis comparing epidural, patient-controlled intravenous morphine, and continuous wound infiltration for postoperative pain management after open abdominal surgery. Br J Anaesth. 108, 998–1005. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aes091 (2012).

Tran, J., Chan, V. W. S., Peng, P. W. H. & Agur, A. M. R. Evaluation of the proximal adductor canal block injectate spread: a cadaveric study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 45, 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2019-101091 (2020).

Sakai, N., Nakatsuka, M. & Tomita, T. Patient-controlled bolus femoral nerve block after knee arthroplasty: quadriceps recovery, analgesia, local anesthetic consumption. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 60, 1461–1469. https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.12778 (2016).

Roy, M. A. & Doherty, T. J. Reliability of handheld dynamometry in assessment of knee extensor strength after hip fracture. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 83, 813–818. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.phm.0000143405.17932.78 (2004).

Althunian, T. A., de Boer, A., Klungel, O. H., Insani, W. N. & Groenwold, R. H. Methods of defining the non-inferiority margin in randomized, double-blind controlled trials: a systematic review. Trials. 18, 107. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-1859-x (2017).

Acknowledgements

Dr. Tomohiro Michino (Department of Anesthesiology, Daiyukai General Hospital, Ichinomiya, Japan) for his advice and generous contribution to the data analysis and manuscript preparation. Enago, a member of Crimson Interactive Pvt. Ltd. (http://www.enago.com/), contributed to the proofreading and editing of this manuscript.

Funding

The authors have no sources of funding to declare for this manuscript from any funding agency in public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors designed the study protocol. N.S., T.A., T.S., C.T., and Y.U. recruited patients and conducted this study. N.S. and T.A. analyzed the data, and C.T., T.S., and Y.U. interpreted the study data. M.T. supervised the entire study process. N.S. prepared the first draft of the manuscript, and then all authors revised it and approved the final version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The Institutional Review Board of Daiyukai General Hospital approved the trial protocol (No. 2019-024, March 4, 2020), and all participating patients provided written informed consent. The study was registered in the National Registry (Study ID: UMIN40054: https://center6.umin.ac.jp/cgi-open-bin/ctr_e/ctr_view.cgi?recptno=R000045668, April 4, 2020) before patient recruitment. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Presentation

The abstract of this trial was presented at the 39th Annual Congress of The European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy in Thessaloniki, Greece, on June 23, 2022.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sakai, N., Adachi, T., Sudani, T. et al. Popliteal plexus block compared with tibial nerve block on rehabilitation goals following total knee arthroplasty: a randomized non-inferiority trial. Sci Rep 14, 23853 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74951-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74951-y