Abstract

Iron Formations (IF) are threatened by mining, particularly the Mesovoid Shallow Substratum (MSS), an understudied subterranean environment. We evaluate the spatiotemporal patterns of subterranean fauna in MSS of iron duricrust (canga) in the Iron Quadrangle and Southern Espinhaço Range, southeastern Brazil. Samplings took place between July 2014 and June 2022 using five trap types. We sampled 108,005 individuals, 1,054 morphospecies, and seven phyla, globally the largest dataset on MSS in IF. Arthropoda represented 97% of all invertebrates sampled. We identified 31 troglomorphic organisms, primarily Arthropoda and Platyhelminthes. MSS traps were the most efficient method, capturing 80% of all invertebrates. Morphospecies were more prevalent in each locality than shared among localities. Species replacement was the main processes to spatial differences. Over time, we found a decrease of total dissimilarity and importance of species replacement for troglomorphic organisms. A positive correlation between spatial distance and compositional dissimilarity of invertebrates was found. Iron Quadrangle and Southern Espinhaço Range showed marked differences in the spatiotemporal patterns of subterranean fauna. Brazilian IF are threatened, with their biological significance not fully understood but highly endangered due their limited distribution. Conservation efforts require a comprehensive understanding of both biotic and abiotic factors shaping the entire IF ecosystem.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Iron Formation (IF) is a broad term for iron-rich rocks including (and derived from) the original Banded Iron Formation (BIF) deposits. These ancient rock formations, dating back from the Proterozoic (3.5–2.5 Gy), are of high economic value as the main source of iron (Fe)1. Most of these IF deposits are currently restricted to a few areas in Earth’s surface (Australia, Brazil, Canada, Russia, and eastern/southern Africa), commonly associated with tectonically stable settings in old cratonic regions2,3. The economic value of IF has resulted in a dramatic increase in mining activities that causes severe threat to this conspicuous and quite limited ecosystem4,5,6. In Brazil, IF rocks comprise approximately 0.1% of the Brazilian landmass, with major deposits in the Amazonian area of the Carajás plateau in northern Brazil, and in the Iron Quadrangle (IQ) and Southern Espinhaço Range (SE), both in southeastern Brazil7. Brazil holds the position as the world’s second-largest exporter of iron ore, representing a noteworthy 74% of Brazil’s mineral exports in 2021, a surge from 66% in 20208. This economic setting has had considerable impact on the conservation of caves and other subterranean environments in iron-rich landscapes.

IF regions in Brazil are usually capped (and protected from erosion) by canga, an iron-rich conglomerate usually a few meters thick. Canga is particularly porous, containing joints and fractures, which harbor pores of different sizes including caves9. Canga pores, therefore, establish connections with epigean environments, such as soil, rock compartments, and leaf litter, serving as vital connectivity elements for invertebrate fauna between macro caves and other subterranean habitats10,11,12. Canga represents a previously unrecognized subterranean ecosystem and can be seen as a type of Mesovoid Shallow Substratum (MSS)13, also known as a shallow (superficial) subterranean habitat with intermediate-sized spaces and connections with the surface14. Hence, canga provides a diverse subsurface habitat inhabited by fauna adapted to subterranean environments12,15,16. In the Brazilian Atlantic Forest, the fauna adapted to caves and similar environments within IF landscapes show higher diversity compared to fauna associated with other types of rock formations like carbonate, magmatic, and siliciclastic rocks17. However, this outstanding biodiversity and many aspects of broad-scale spatiotemporal patterns of organisms in the canga MSS environments are still unknown18.

Research interest in MSS habitats is increasing since they represent a shallow subterranean habitat of significant conservation importance because of the many invertebrates, both endemic and specialized for subterranean life, found in it18. For instance, some authors have found that IF caves and MSS are hotspots for subterranean Collembola (either troglophile or troglobiotic) in southeastern Brazil19. The MSS serves as a climatic and reproductive refuge, functions as a biogeographic corridor, and can also serve as a permanent habitat20. Some species inhabiting the MSS have specialized traits such as a marked degree of troglomorphism associated with this type of habitat21, thus allowing the occurrence of troglobiotic species (restricted to the subterranean environment). These ecosystems, in recent years, have been the subject of studies for environmental licensing purposes in Brazil, as they occur in areas of high mineral interest22. Faunistic surveys in IF caves and MSS in Brazil have indicated a diverse fauna, including records of troglobiotic and troglomorphic species18,23,24,25. Studies of the spatiotemporal distribution of biological groups in canga MSS are, however, still limited11,18,25, hence leaving a unique and highly threatened environment with little information about its biodiversity.

Evaluating the diversity patterns of the subterranean fauna allows us to verify if there is a connection between the macro cavities18. This is an argument that can be used for the delimitation of the surrounding protective area necessary to ensure the maintenance of the ecological integrity of cavities, according to the Brazilian legislation on caves26,27. Therefore, studying the subterranean fauna in the canga MSS has great potential for expanding the knowledge about the distribution of biological populations, allowing a better understanding of the IF systems. Essential discussions involve the composition of the troglobiotic fauna in the iron rocks and the extension of the subterranean environment, considering the subterranean system as a whole and not only the macro cavities accessible to humans28,29,30. The combination of complementary sampling methods allows access to different subterranean habitats and expands the knowledge and understanding of these environments31.

Here we evaluate the distribution of the subterranean invertebrate fauna inhabiting the canga MSS in the Iron Quadrangle and Southern Espinhaço Range in southeastern Brazil. Our comprehensive dataset, the largest so far in this type of rock, is based on the compilation of distribution data of species sampled with different types of traps in three long-term monitoring projects. Specifically, we aimed to characterize the fauna associated with the canga MSS in southeastern Brazil and discuss the highly threatened nature of this environment due to increasing iron mining activities. We compare the effectiveness of the five sampling methods and describe the spatiotemporal patterns of beta diversity (i.e., compositional changes) for the whole community and troglomorphic organisms. We also assess the existence of a correlation between compositional changes and spatial distance, which can bring insights into the connectivity within the IF environment.

Materials and methods

Study area

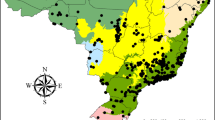

Our database consists of data from three monitoring projects carried out to evaluate the invertebrate fauna in the IQ and the SE, two geographically adjacent regions located in the state of Minas Gerais, southeastern Brazil (Fig. 1). The study region comprises an ecotone between the Atlantic Forest and Cerrado (Brazilian savannah-like ecosystem), where relic communities of mountain vegetation also occur. In the region on the eastern edge of the Espinhaço, a montane semideciduous seasonal forest predominates, with forested and woody grassland savannahs occurring as well, along with upper-mountain and montane refuges. The climate is highly seasonal, with an average annual temperature of 20.6 °C in the sampled locations, with the highest monthly averages in February (summer; 23.2 °C) and the lowest in July (winter; 16.6 °C). The annual accumulated precipitation is 1424.4 mm, while the average annual relative humidity is 76.1%. The rainiest months extend from October to March. The months from April to September are marked by the dry season32.

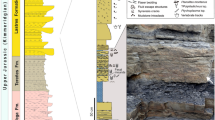

The IF regions of southeastern Brazil have undergone a complex geological and tectonic evolution, involving both hypogene (mineralization related to deep sources of ascending fluids) and supergene (mineralization near the surface due mainly to meteoric solutions) iron mobilization, resulting in the formation of resilient IF ridges. The iron-rich beds belong to the Cauê Formation and constitute a part of the larger BIF deposited between 2.52 and 2.42 Gy33. The IF of the Southern Espinhaço Range are situated near the IQ, sharing many climatic and vegetational characteristics. These formations, rich in Fe, consist of two distinct sequences separated by an erosional unconformity. They are part of the Serra do Sapo Formation, part of the Serra da Serpentina Group and the Canjica Formation which belongs to the São José Group, with depositional ages of 1.99 and 1.66 Gy, respectively34. Both BIF sequences exhibit similar features, characterized by alternating bands of hematite-rich and quartz-rich layers, ranging from millimeters to centimeters in thickness. Like the IQ, the SE iron deposits predominantly outcrop at the top and flanks of irregular, roughly north-south trending ridges. Iron mining operations in the SE region only commenced in the early 2010s, and as a result, most of the IF deposits remain relatively preserved35. In both areas there is widespread occurrence of canga, a much younger iron-rich duricrust that comprises fragments of iron rocks cemented by a ferruginous matrix36,37. Silica leaching and iron bacterial mobilization resulted in a highly heterogeneous IF habitat with elevated porosity36,38,39, with porosity values reaching as much as 24%40. Besides widespread microporosity represented by mm-scale interconnected pores, canga and weathered BIF host thousands of caves10,35,41. Although of variable size, the pore spaces within canga retain rainwater and organic matter, slowly percolating into deeper rock layers and caves. These organic-rich habitats, often persistently wet or humid, create a permeability contrast with the less permeable IF units underneath.

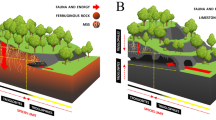

The three monitoring projects in both IF are described as follows: (1) Brumadinho (BRU). The invertebrate sampling was carried out in 20 sampling units located in Serra do Rola Moça, Brumadinho, Minas Gerais, Brazil (20º09’31”S, 43º58’26”W, 1503–1581 m a.s.l.), which belongs to the IQ domain. The sampling units were monitored during 24 campaigns carried out between April 2018 and June 2022. To sample the fauna in BRU, we used only traps developed for surface/shallow subterranean spaces (MSST traps; Fig. 2; see Appendix S1 in the Supplementary information for detailed trap description)42. (2) Itabirito (ITA). Samplings were carried out during July 2014 to May 2016 in Serra da Moeda (20º17’58”S, 43º56’46”W, 1490–1420 m a.s.l.), which is located in the southwestern portion of the IQ. The following sampling methods were used: MSS traps (MSST; N = 28); MSS traps with leaf litter (MSSL; N = 45), depth traps (DEPT; N = 18), flexible leaf litter traps (FLLT; N = 39), and drip traps (DRIT; N = 9; Fig. 2; see Appendix S1 in the Supplementary information for detailed trap description). (3) Conceição do Mato Dentro (CMD). The sampling was carried out in canga sites of Serra do Sapo, located in the municipality of Conceição do Mato Dentro (19º00’17”S, 43º23’43”W, 848–991 m a.s.l.), which belongs to the SE domain. We sampled biological groups using the following sampling methods: MSS traps (MSST; N = 20), MSS traps with leaf litter (MSSL; N = 20), flexible leaf litter traps (FLLT; N = 53), and drip traps (DRIT; N = 8; Fig. 2; see Appendix S1 in the Supplementary information for detailed trap description) between September 2015 and July 2016.

Schematic profile of an IF cave and surroundings, and trap types used to sample the IF invertebrate fauna in the three study sites of Minas Gerais, southeastern Brazil (BRU, ITA, and CMD). Classic MSS traps (MSST), MSS traps with leaf litter (MSSL), depth traps (DEPT), flexible leaf litter traps (FLLT), and drip traps (DRIT). See Appendix S1 for detailed description of traps.

Laboratory procedures

The samples were sorted and kept in 70% alcohol for preservation. After sorting, the organisms were separated into morphospecies and identified using dichotomous keys for orders and families of invertebrates. All material was sent to specialists for confirmation or refinement of identifications, as well as for analysis of possible endemism and troglomorphism (see Acknowledgments). Voucher specimens were deposited in the Museu de Ciências Naturais of the Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais (Annelida, Entognatha, Insecta, Malacostraca, Maxilipoda, Mollusca, Nematoda, Onychophora, and Platyhelminthes), Collection of Arachnids and Miriapods of the Laboratório Especial de Coleções Zoológicas of the Butantan Institute (Arachnida and Myriapoda), and Soil Fauna Reference Collection of the Universidade Estadual da Paraíba (Collembola).

Statistical analysis

We used the R analytical environment to carry out our analysis43. First, we compiled and described general patterns of (morpho)species richness and abundance of the invertebrate fauna as a whole and for troglomorphic organisms by locality and by type of trap used. The number of unique and shared species by trap type was described using Venn Diagrams.

Species accumulation curves were generated for both the whole community and troglomorphic species, using abundance per location and per sampling method throughout the sampling period. The objective was to assess sample completeness and compare species diversity profiles. To compare curves between locations, we only used data from classic MSS traps, as it was the only common method among the three locations. Only the CMD and ITA locations were used to compare sampling methods, since both used at least four different methods and the BRU location only used classic MSS traps. We estimated the sample coverage or completeness using Hill numbers44,45. Hill numbers, or the effective number of species, comprise a mathematically unified group of diversity indices (differentiated solely by an exponent q) that integrate both species richness and relative abundance into their calculations44. We used Hill numbers of q = 0 (which represents the species richness) to calculate the sample size-based rarefaction and extrapolation curves by doubling the reference sample44,46. For extrapolated portions of the curves, the number of individuals was twice the actual reference size44. The sample coverage based on the final slope of this curve was estimated with 100 bootstrap replications and implemented using the “iNEXT” R package46.

The Sorensen dissimilarity, a measure of incidence-based β-diversity (βSOR), was used to assess spatial and temporal variations in species composition per location using only the classic MSS traps. This analysis was carried out separately for the whole community and troglomorphic species. Spatial β-diversity was utilized to quantify dissimilarity in species composition among the MSS points, while temporal β-diversity measured the variation in species composition at each sampling point over the sampling period. To elucidate the main drivers of species composition variation, the spatial and temporal β-diversity (Sorensen dissimilarity) values were partitioned into species replacement and richness difference47. We used the Podani’s approach for this purpose47 using the “beta.multi” function of the “BAT” R package48.

We used Mantel tests to evaluate the correlation between species composition dissimilarity and spatial distance between sampling points49. Spatial distance was estimated using UTM coordinates of latitude and longitude of each sampling point. We carried out this analysis for the whole dataset and for each locality using classic MSS traps only. These analyses were carried out separately for the whole community and troglomorphic species. Bray-Curtis dissimilarity and Euclidean distance were used to calculate the community dissimilarity and spatial distance, respectively. We used the function “mantel” of the “vegan” R package50 with the Spearman correlation coefficient and 9,999 permutations.

Results

We sampled 108,005 individuals and 1,054 morphospecies (Table S1) belonging to seven phyla: Annelida (S = 12, N = 1,534), Arthropoda (S = 1,009, N = 105,767), Mollusca (S = 19, N = 56), Nematoda (S = 4, N = 8), Onychophora (S = 1, N = 1), Platyhelminthes (S = 5, N = 39), and Rotifera (S = 4, N = 600) (Table 1; Fig. 3a). We found 2,772 individuals of 31 morphospecies of troglomorphic fauna, belonging to two phyla: Arthropoda (S = 28, N = 2,735) and Platyhelminthes (S = 3, N = 37) (Table 2; Fig. 3a). Pseudosinella sp.1 (Collembola: Entomobryidae), Arrhopalites coecus (Tullberg, 1871) (Collembola: Arrhopalitidae), Pararrhopalites sp.11 (Collembola: Symphypleona), Pseudosinella sp.5 (Collembola: Entomobryidae), Pararrhopalites sp.2, and Pararrhopalites sp.3 represented together 82.5% of the troglomorphic species sampled. These Pseudosinella spp. occurred in all three localities, being sampled more frequently with flexible leaf litter traps followed by classic MSS traps (Table 2). A. coecus also occurred in all three localities, while these Pararrhopalites spp. were sampled only in BRU and ITA exclusively or mostly with classic MSS traps (Table 2).

Distribution of abundance (square-rooted) of the invertebrate phylum (upper panels) and Arthropoda class (lower panels) sampled in Brumadinho (BRU), Itabirito (ITA), and Conceição do Mato Dentro (CMD), and as a whole (Total) using different traps (DEPT: depth traps; DRIT: drip traps; FLLT: flexible leaf litter traps; MSSL: MSS traps with leaf litter; MSST: classic MSS traps). Phylum and class names were ordered alphabetically. Inset plots in ‘a’ and ‘c’ represent the same for troglomorphic organisms. Silhouettes of organisms are not to scale.

Among localities, Arthropoda represented more than 97% of all invertebrates sampled (BRU = 97.3%; ITA = 99.4%; CMD = 97.2%; Fig. 3a). Among these, insects were the most abundant, representing 77.7%, 64.5%, and 54.1% of all individuals sampled in BRU, ITA, and CMD, respectively (Fig. 3b). Arachnida was the second most abundant group in BRU (11.2%) and CMD (34.0%), while Collembola was the second most abundant in ITA (33.9%) (Fig. 3b). Among the sampling methods, we found that classic MSS traps sampled almost 80% of all invertebrate fauna, while depth traps were the second most efficient method in terms of invertebrate abundance (15.4%) (Fig. 3c). Flexible leaf litter traps, drip traps, and MSS traps with leaf litter sampled only 3.3, 0.8%, and 0.07% of the total individuals (Fig. 3d).

The number of shared morphospecies among the three localities was lower than the number of unique morphospecies found in each locality (Fig. 4a). BRU has the most unique invertebrate fauna among the localities sampled, with 401 morphospecies (38%). ITA had the second higher relative number of unique morphospecies (S = 211; 20%), while CMD had only 132 unique morphospecies (12.5%). Among the sampling methods, classic MSS traps was the most efficient in terms of unique morphospecies (S = 744; 70.6%) (Fig. 4b). Classic MSS traps plus flexible leaf litter traps were the second most efficient in number of morphospecies (S = 65; 6.2%). Flexible leaf litter traps sampled 50 unique morphospecies (4.7%), depth traps sampled 29 unique morphospecies (2.8%), while only 10 morphospecies (0.09%) were sampled in drip traps. For troglomorphic organisms, we found a similar pattern, with unique troglomorphic species showing high numbers in BRU and ITA (S = 9 in both), while shared species between two or three localities were low (S ≤ 4) (Fig. 4c). Among trap types, troglomorphic organisms were better sampled using classic MSS traps and classic MSS plus flexible leaf litter traps (Fig. 4d). No troglomorphic species was sampled in four or more types of traps.

Number of unique and shared morphospecies of invertebrate fauna sampled in Brumadinho (BRU), Itabirito (ITA), and Conceição do Mato Dentro (CMD) (upper panels) using different traps (MSST: classic MSS traps; MSSL: MSS traps with leaf litter; DEPT: depth traps; FLLT: flexible leaf litter traps; DRIT: drip traps) (lower panels). Left panels represent the whole invertebrate community; right panels represent the troglomorphic species.

The interpolation and extrapolation curves and sample coverage values indicated a good representation of the invertebrate fauna sampled in MSS traps in all localities (BRU: S = 658, SC [sample coverage] = 0.997; ITA: S = 346, SC = 0.992; CMD: S = 274, SC = 0.996) (Fig. 5, upper, left panel). However, BRU had 3.8 and 2.8 times more individuals than ITA and CMD, respectively. Classic MSS traps were the most successful in terms of species richness when compared to other traps (Fig. 5, central and lower left panels). Flexible leaf litter traps had the second largest number of morphospecies and individuals sampled in both ITA and CMD localities (ITA: S = 95, N = 2036, SC = 0.987; CMD: S = 92, N = 1490, SC = 0.973). For the troglomorphic fauna sampled using MSS traps, we also found a high sample coverage in all localities (BRU: S = 17, SC [sample coverage] = 0.986; ITA: S = 15, SC = 0.999; CMD: S = 7, SC = 1.000) (Fig. 5, upper, right panel). ITA, however, showed the largest number of troglomorphic individuals sampled (ITA: N = 1430; BRU: N = 350; CMD: N = 99). When sampling methods are compared, MSS traps also sampled the greatest troglomorphic richness and abundance (ITA: S = 15, N = 1430, SC = 0.999; CMD: S = 7, N = 99, SC = 1.00) (Fig. 5, central and lower right panels). In both ITA and CMD localities, the FLL traps had the second largest number of morphospecies sampled. This method also was the second in terms of abundance in ITA, while drip traps was for CMD.

Sample-size based rarefaction (solid line segment) and extrapolation (dotted line segments) sampling curves with 95% confidence intervals (shaded areas) for the whole community (left panels) and troglomorphic (right panels) invertebrate fauna sampled in Brumadinho (BRU), Itabirito (ITA), and Conceição do Mato Dentro (CMD). Traps used: classic MSS traps (MMST), MSS traps with leaf litter (MSSL), depth traps (DEPT), flexible leaf litter traps (FLLT), and drip traps (DRIT). Upper panels show curves for MSS traps only for each locality. Central and lower panels show curves for the same four sampling methods used in ITA and CMD localities. Depth traps used in ITA were not shown for clarity.

The partitioning of β-diversity revealed that species replacement contributed more than richness differences spatially (among MSS sites in each locality) for both the whole community and troglomorphic organisms, with higher values for the whole community (Fig. 6a, b). Over time, we found a variable temporal pattern for the whole community: BRU and CMD were dominated by species substitution, while ITA had an increased compositional dissimilarity, mostly represented by richness differences (Fig. 6c). Temporal β-diversity partitioning indicated a higher compositional dissimilarity of troglomorphic organisms for both BRU and ITA, mostly represented by species replacement. For CMD, we found a lower temporal dissimilarity, with both components of replacement and richness differences playing a similar role (Fig. 6d).

Partition of β-diversity (Sorensen dissimilarity) of whole community (left panels) and troglobiotic organisms (right panels) sampled in the canga MSS into their replacement and richness difference components for Brumadinho (BRU), Itabirito (ITA), and Conceição do Mato Dentro (CMD). Upper panels: spatial β-diversity (between sampling sites); lower panels: temporal β-diversity (between sampling campaigns).

We found that the increase in spatial distance was positively correlated with the increase in dissimilarity of the whole community and troglomorphic organisms sampled in the canga considering all trap types and only classic MSS traps (Fig. 7). This pattern also occurred in BRU for both groups and in ITA for the whole community. We found no correlation in CMD for both groups and for troglomorphic organisms in ITA (Fig. 7).

Spearman correlation between spatial distance (Euclidean distance) and community dissimilarity (Bray-Curtis dissimilarity) of the invertebrate fauna Brumadinho (BRU), Itabirito (ITA), and Conceição do Mato Dentro (CMD). Left panels show results for the whole community; right panels show results for troglomorphic organisms. The analysis was carried out using all traps (a, f), classic MSS traps (b, g), classic MSS traps from BRU (c, h), classic MSS traps from ITA (d, i), and classic MSS traps from CMD (e, j).

Discussion

Our results revealed an outstanding biodiversity of invertebrates sampled using different types of traps in the canga MSS from the Iron Quadrangle (IQ) and the Southern Espinhaço Range (SE) in southeastern Brazil. This includes some troglomorphic organisms. In many subterranean habitats, such as the canga MSS, there is a continuing flux of migrants from the soil and surface fauna to the MSS. This flow can be caused actively (e.g., migration, foraging) or passively (e.g., flood, wind, gravitation)14. Some deep soil and deep litter invertebrate fauna can be eyeless and pigmentless (edaphomorphy). Troglomorphic organisms are those when additional traits, such as appendage elongation or larger body size, are present51,52. Together with the organisms obligatorily associated with the MSS, these soil and surface invertebrates contribute to the high diversity of organisms found in this type of subterranean environment.

We found some marked differences in the invertebrate biodiversity between IQ (BRU, ITA) and SE (CMD). For instance, CMD had lower total species richness and abundance, and fewer troglomorphic species and their abundance than either BRU or ITA, considering only classic MSS traps with similar sampling effort in these localities. Differences in iron outcrops’ area and shape may have an influence on these results. The area of iron formations in SE was estimated at 34.2 km2 with a narrow and elongated shape comprising an almost single outcrop, plus a few adjacent areas in its southern portion34,35. In IQ, the iron formations were estimated to cover 186.4 km2 with several occurrences of outcrops spread over an area much larger than SE4,35. The relationship between the number of species and the area sampled is a well-established and widely reported ecological phenomenon. It has been documented across different taxa and spatial scales53. Additional factors such as differences in canga thickness and porosity and in local climatic and environmental conditions between IQ and SE deserve future investigation to elucidate the main processes behind such patterns.

Unique invertebrate morphospecies and troglomorphic organisms were more prevalent in each locality than shared among localities. This pattern of having numerous geographically rare species alongside a small number of geographically widespread ones is likely a common occurrence across subterranean fauna overall14. Additionally, BRU and ITA (IQ) shared more species than both shared with CMD (SE). This result is explained by the geographic proximity between the two areas of IQ in relation to SE. Biological communities are assembled by factors such as dispersal limitations, environmental heterogeneity, and interactions among organisms. Additionally, stochastic variations can also influence patterns of species distribution54. Differences in spatial distance also proved to be determinant in the compositional differences of invertebrates between the three sampled localities. Increased spatial distance led to greater dissimilarity in biological composition between IQ and SE. This pattern was robust considering the whole community and troglomorphic organisms, either using all trap types and classic MSS traps only. Within each locality, we found a similar response pattern of invertebrates only in BRU. ITA showed the same pattern but only for the whole community. Interestingly, the pattern was not maintained in CMD for any of the groups evaluated, adding yet another striking difference in the diversity patterns of invertebrates sampled in the MSS between IQ and SE. The invertebrate fauna sampled in the MSS, especially those obligatory adapted to the subterranean environment, is expected to exhibit some degree of dispersal limitation due to biotic and abiotic requirements14. Therefore, one would expect that the composition will change substantially as spatial distance, environmental heterogeneity, and interaction with different species increase across the IF sampled.

Arthropoda dominated in all localities followed by Annelida in BRU and ITA (IQ), but in CMD (SE), Rotifera was more abundant than Annelida as the second more representative group. All Rotifera organisms were found in samples using drip traps as these are aquatic and microscopic animals. The greater occurrence of Arthropoda, mainly represented by Insecta, Collembola, and Arachnida, is a robust pattern among studies on the MSS fauna55. The consistent prevalence of epigean species within the different types of MSS has been a recurrent observation in previous studies55, including the canga MSS18. The MSS acts as a climatic and reproductive refuge, operates as a biogeographic pathway, and may also function as a permanent habitat for many organisms20. In congruence, classic MSS traps sampled the most representative fauna of most phylum, except for all Rotifera (aquatic organisms) and one Onychophora (terrestrial organisms). Since their creation, classic MSS traps have been demonstrated to be a robust collection method for sampling representative and diverse subterranean fauna, including troglomorphic and troglobiotic organisms42. Excluding classic MSS traps, some organisms (S = 9 to 50) were sampled exclusively in each trap type. In ITA and CMD, localities with more trap types, the complementarity of other traps to classic MSS traps in sampling troglomorphic organisms was low. However, some organism groups were found in only one trap type: Folsomina sp.1 (Collembola) was found only using depth traps in ITA; Folsomiella sp.1 and Pygmarrhopalites sp.1 (Collembola) were sampled only using FLL traps in ITA; Bryocyclops sp.1 was sampled only using drip traps in CMD. Therefore, the use of other types of traps in addition to classic MSS traps can be useful to evaluate population dynamics of certain groups, in addition to complementing the MSS sampling.

Faunal composition of MSS is dynamic spatially and temporally, with profound effects of the rock porosity and compaction on migration between MSS and either deep hypogean or epigean layers55. This pattern is also expected between MSS sites in different portions of the canga near the surface. Some authors have found differences in the spatiotemporal patterns of troglobiotic and non-troglobiotic organisms inhabiting the canga MSS over space (between MSS sites) and time (between samplings)18. Spatially, our results showed that species replacement is the main process of compositional change for the whole community and troglomorphic organisms regardless of locality. Over time, ITA has an increased dissimilarity represented by both components of β-diversity, while BRU and CMD showed increased importance of species replacement for the whole community. However, for troglomorphic organisms we found an interesting pattern, with a decrease of dissimilarity and importance of species replacement from BRU to ITA (IQ) to CMD (SE). Differences in climatic conditions over time between these two large regions may have influenced such patterns, but this topic still needs to be better addressed since other environmental variables (e.g., vegetation, soil conditions) may also be important.

Species richness and abundance of the invertebrate fauna are expected to decrease with increasing depth in the MSS56,57,58, as the result of the decrease in available organic matter with increasing depth59 and change in conditions in the rock (e.g., water retention, lower temperature compared to top layers) and the surface (e.g., more cold/hot or rainy/dry conditions)60,61. This can cause a migration of epigean species into MSS to escape harsh surface conditions, which increases the richness and abundance of the MSS fauna near the surface60,61. These resource and condition variations are expected to cause a compositional change between the top and deep layers of the canga MSS, with some groups, such as Rotifera, being sampled only using drip traps. Depth traps (up to 5 m deep) also proved to be very relevant, being the second most efficient method in terms of abundance of invertebrates sampled, even though it was used in only one location (ITA). Canga can be up to 30 m thick but normally is just a few meters40. Therefore, one can expect that the associated fauna across the depth of the canga is different and the complementarity of collection methods is essential for a more representative sampling. Sampled restricted groups in drip traps also highlights the connectivity of the canga MSS with the interior of the caves. To understand the connectivity between the subterranean system and other connected cavities near the cave, Brazilian legislation recommends utilizing troglobiotic species as “biological tracers”27. Our investigation reveals high heterogeneity in the distribution of troglomorphic organisms (some potentially troglobiotic) within the canga MSS, a system intricately linked to caves. This result raises questions regarding the use of these organisms as “biological tracers” to indicate the connectivity of the subterranean system based solely on their presence in caves or MSS, as pointed out by Dornellas and colleagues18, despite the expected natural connectivity inherent in the environment due to the physical properties of the rock35. However, while our findings demonstrate considerable spatial variation in the composition of this fauna, it does not conclusively determine that there would or would not be evidence for gene flow between populations of the same species. Additionally, while previous studies have suggested that IF caves harboring more troglobiotic species exhibit lower species replacement values, considering them more ecologically “stable”62,63, we found high total β-diversity values in the canga MSS for both troglomorphic and the whole community. This observation reinforces the notion of moderate-to-low ecological connectivity between sampling sites in the MSS, despite the environment’s conditions for fauna evolution and persistence.

Until 2018, Brazil had 150 described obligatory subterranean species, distributed over 12 states and located in different lithologies and geomorphologic groups64. Most species were sampled in limestone rocks (S = 123), with only 12 species occurring in iron formations64. This demonstrates a range of possibilities for finding new species and expanding their distribution with the expansion of studies in canga formations that include small subterranean environments (e.g., MSS) to large caves. Among the identified troglomorphic species, we found one spider, Brasilomma enigmatica Brescovit, Ferreira & Rheims, 2012, sampled only with classic MSS traps in BRU. This species has previously been known from three caves with different formations (i.e., limestone, quartizite, and IF), all of them far apart from each other (60–180 km) in Minas Gerais65. Species of Pseudochthonius Balzan, 1892 (Pseudoscorpiones: Chthoniidae) have been listed as obligatory subterranean fauna in differences regions of Brazil, including Minas Gerais64,66. The genus includes 34 species, with 14 species occurring in Brazil, most considered troglobiotic species66,67. We sampled one unidentified, troglomorphic species of Pseudochthonius from canga formation using mostly classic MSS traps but also FLL traps. Detailed taxonomic examination of these individuals may lead to the separation into one or more species, as we collected individuals in IQ and SE.

Two unidentified species of Trogolaphysa Mills, 1938 (Collembola: Entomobryidae) were found in classic MSS traps from ITA and CMD. Many species of Trogolaphysa have been associated obligatorily with iron rock formations in southeastern Brazil19,64. Pararrhopalites sideroicus Zeppelini & Brito, 2014 and more six unidentified species (Collembola: Sminthuridae) were sampled mostly using classic MSS traps, found in higher numbers in ITA but some species also occurred in BRU. Two other species of Pararrhopalites Bonet & Tellez, 1947 have been associated obligatorily to limestone formations in Mato Grosso do Sul and São Paulo64. Arrhopalites coecus (Tullberg, 1871) was mostly sampled in depth traps and classic MSS traps, but also in FLL traps, occurring in all localities. Seven species of Arrhopalites C.Börner, 1906 are associated obligatorily with limestone formations in Santa Catarina, Paraná, and São Paulo64. We also found three unidentified species of Platyhelminthes from two families (Dugesiidae and Geoplanidae) sampled using only classic MSS traps in BRU. These findings highlight the potential for discovering new species of troglomorphic organisms within the IF ecosystem.

Conclusion

Caves and adjacent subterranean environments, such as the MSS, are increasingly threatened in Brazil with recent changes in the criteria for designating priority subterranean areas for conservation6,22. The MSS environment stands out for being much less studied compared to caves that attract the attention of tourists and policymakers, even though the associated fauna is very diverse, abundant, and specialized18,19. In this study, using a comprehensive dataset we demonstrate the high diversity of invertebrate organisms, including many troglomorphic species, that inhabit the canga MSS environments in three localities that encompass the Iron Quadrangle and the Southern Espinhaço Range. The invertebrate fauna of the canga MSS is highly diverse and abundant but clear differences stand out between these two geological formations.

Classic MSS traps demonstrated the highest efficiency, followed by depth traps. However, the combined use of different collection methods proved essential for achieving a more comprehensive inventory of the MSS. Certain types of traps were found to be more effective for specific groups of organisms, highlighting the importance of methodological complementarity in sampling strategies. Species replacement primarily drives spatial differences in β-diversity, with a variable pattern among localities over time and a positive correlation between spatial distance and compositional dissimilarity of invertebrates observed in the Iron Quadrangle but not in the Southern Espinhaço Range. These indicate a moderate-to-low ecological connectivity or a certain degree of isolation of the subterranean invertebrate fauna, according to the high rates of spatial and temporal species replacement we found. These results reinforce over a broad spatial extent some local patterns previously found in the same system18.

Mining activities pose a significant threat to Brazilian IF. These IF harbor unique ecosystems with both known and potentially undiscovered species, contributing to Brazil’s biodiversity. The biological relevance of these ecosystems is not fully understood, but they are considered highly endangered due to the limited distribution of IF across Brazil. Therefore, effective preservation efforts require a comprehensive understanding of both biotic and abiotic components shaping the entire IF ecosystem. This includes evaluating the biodiversity patterns within IF, understanding their ecological interactions, and assessing the impacts of mining activities. By gaining a holistic understanding of IF ecosystems, conservationists can develop strategies to mitigate the threats posed by mining and ensure the long-term preservation of these unique and threatened environments.

Data availability

The data analyzed are available as supplementary material.

References

Cloud, P. Paleoecological significance of the Banded Iron-formation. Econ. Geol. 68, 1135–1143. https://doi.org/10.2113/gsecongeo.68.7.1135 (1973).

Bekker, A. et al. Iron formation: the sedimentary product of a complex interplay among mantle, tectonic, oceanic, and biospheric processes. Econ. Geol. 105, 467–508. https://doi.org/10.2113/gsecongeo.105.3.467 (2010).

Klein, C. Some precambrian banded iron-formations (BIFs) from around the world: their age, geological setting, mineralogy, metamorphism, geochemistry, and origin. Min. 90, 1473–1499. https://doi.org/10.2138/am.2005.1871 (2005).

Salles, D. M., Carmo, F. F. & Jacobi, C. M. Habitat loss challenges the conservation of endemic plants in mining-targeted Brazilian mountains. Environ. Conserv. 46, 140–146. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892918000401 (2019).

Souza-Filho, P. W. M. et al. Mapping and quantification of ferruginous outcrop savannas in the Brazilian Amazon: a challenge for biodiversity conservation. PLoS ONE. 14, e0211095. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211095 (2019).

Ferreira, R. L. et al. Brazilian cave heritage under siege. Science. 375, 1238–1239. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abo1973 (2022).

Rosière, C. A. & Chemale, F. Jr. Brazilian iron formations and their geological setting. Braz J. Geol. 30, 274–278 (2000).

Brasil Brazil stands out in the export of iron ore, (2022). https://www.gov.br/en/government-of-brazil/latest-news/2022/brazil-stands-out-in-the-export-of-iron-ore

Piló, L. B., Coelho, A. & Reino, J. C. R. in Geossistema Ferruginosos: áreas prioritárias para conservação da diversidade geológica e biológica, patrimônio cultural e serviços ambientais (eds F. F. Carmo & L. H. Y. Kamino) 125–148 (3i Editora, 2015).

Culver, D. C. & Pipan, T. Superficial subterranean habitats – gateway to the subterranean realm? Cave Karst Sci. 35, 5–12 (2008).

Ferreira, R. L., de Oliveira, M. P. A. & Souza Silva, M. in In Cave Ecology. 435–447 (eds Moldovan, O. T., Kováč, Ľ. & Halse, S.) (Springer, 2018).

Auler, A. S., Parker, C. W., Barton, H. A. & Soares, G. A. in In Encyclopedia of Caves. 559–566 (eds White, W. B., Culver, D. C. & Pipan, T.) (Academic, 2019).

Juberthie, C., Delay, B. & Bouillon, M. Extension Du milieu souterrain en zone non-calcaire: description d’un nouveau milieu et de son peuplement par les coleopteres troglobies. Mem. Bioespol. 7, 19–52 (1980).

Culver, D. C. & Pipan, T. Shallow Subterranean Habitats: Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation (Oxford University Press, 2014).

Trevelin, L. C. et al. Biodiversity surrogates in amazonian iron cave ecosystems. Ecol. Indic. 101, 813–820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.01.086 (2019).

Ferreira, R. L., Oliveira, M. P. A. & Silva, M. S. in Geossistema Ferruginosos: áreas prioritárias para conservação da diversidade geológica e biológica, patrimônio cultural e serviços ambientais (eds F. F. Carmo & L. H. Y. Kamino) 195–231 (3i Editora, 2015).

Souza-Silva, M., Martins, R. P. & Ferreira, R. L. Cave lithology determining the structure of the invertebrate communities in the Brazilian Atlantic Rain Forest. Biodivers. Conserv. 20, 1713–1729. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-011-0057-5 (2011).

Dornellas, L. M. S. M. et al. Spatiotemporal distribution of invertebrate fauna in a mesovoid shallow substratum in iron formations. Biodivers. Conserv. 33, 1351–1357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-024-02801-4 (2024).

Zeppelini, D. et al. Hotspot in ferruginous rock may have serious implications in Brazilian conservation policy. Sci. Rep. 12, 14871. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18798-1 (2022).

Eusébio, R. P., Fonseca, P. E., Rebelo, R., Mathias, M. L. & Reboleira, A. S. P. S. how to map potential mesovoid shallow substratum (MSS) habitats? A case study in colluvial MSS. Subterr. Biol. 45, 141–156. https://doi.org/10.3897/subtbiol.45.96332 (2023).

Culver, D. C. & Pipan, T. The Biology of Caves and Other Subterranean Habitats (Oxford University Press, 2019).

Oliveira, H. F. M., Silva, D. C., Zangrandi, P. L. & Domingos, F. M. C. B. Brazil opens highly protected caves to mining, risking fauna. Nature. 602, 386. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-00406-x (2022).

Caetano, D. S., Bená, D. C. & Vanin, S. A. Copelatus cessaima sp. nov. (Coleoptera Dytiscidae Copelatinae) first record of a troglomorphic diving beetle from Brazil. Zootaxa. 3710, 226–232. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3710.3.2 (2013).

Bichuette, M. E., Simões, L. B., von Schimonsky, D. M. & Gallão, J. E. Effectiveness of quadrat sampling on terrestrial cave fauna survey - a case study in a neotropical cave. Acta Sci. Biol. Sci. 37, 345–351. https://doi.org/10.4025/actascibiolsci.v37i3.28374 (2015).

Mendonça, D. R. M., Rodrigues, F. P., Argolo, G., Sousa-Silva, M. & Ferreira, R. L. Eficiência de iscas na coleta de artrópodes encontrados no meio subterrâneo superficial em formação ferrífera na Amazônia brasileira. Rev. Bras. Espeleol. 1, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.37002/rbesp.v1i12.2365 (2023).

Brasil Decreto nº 10.935, de 12 de janeiro de 2022. Dispõe sobre a proteção das cavidades naturais subterrâneas existentes no território nacional. (Diário Oficial da União, (2022).

ICMBio/CECAV. Área de influência sobre o patrimônio espeleológico: orientações básicas à realização de estudos espeleológicos. (ICMBio/CECAV. (2022).

Harvey, M. S., Berry, O., Edward, K. L. & Humphreys, G. Molecular and morphological systematics of hypogean schizomids (Schizomida:Hubbardiidae) in semiarid Australia. Invertebr Syst. 22, 167–194. https://doi.org/10.1071/IS07026 (2008).

Smith, G. B., Eberhard, S. M., Perina, G. & Finston, T. New species of short range endemic troglobitic silverfish (Zygentoma: Nicoletiidae) from subterranean habitats in Western Australia’s semi-arid Pilbara region. Rec West. Aust Mus. 27, 101–116. https://doi.org/10.18195/issn.0312-3162.27(2).2012.101-116 (2012).

Humphreys, G., Blandford, D. C., Berry, O., Harvey, M. & Edward, K. Mesa A and Robe Valley Mesas Troglobitic Fauna Survey: Subterranean Fauna Assessment (Biota Environmental Sciences, 2006).

Halse, S. A. & Pearson, G. B. Troglofauna in the vadose zone: comparison of scraping and trapping results and sampling adequacy. Subterr. Biol. 13, 17–34. https://doi.org/10.3897/subtbiol.13.6991 (2014).

INMET. Normais Climatológicas do Brasil. Available at: https (2022). https://portal.inmet.gov.br/normais.

Babinski, M., Chemale, F. & Van Schmus, W. R. The Pb/Pb age of the Minas Supergroup carbonate rocks, Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Brazil. Precambrian Res. 72, 235–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-9268(94)00091-5 (1995).

Rolim, V. K., Rosière, C. A., Santos, J. O. S. & McNaughton, N. J. The Orosirian-Statherian banded iron formation-bearing sequences of the southern border of the Espinhaço Range, Southeast Brazil. J. South. Am. Earth Sci. 65, 43–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2015.11.003 (2016).

Auler, A. S. et al. Silica and iron mobilization, cave development and landscape evolution in iron formations in Brazil. Geomorphology. 398, 108068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2021.108068 (2022).

Spier, C. A., Levett, A. & Rosière, C. A. Geochemistry of canga (ferricrete) and evolution of the weathering profile developed on itabirite and iron ore in the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Min. Deposita. 54, 983–1010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00126-018-0856-7 (2019).

Gagen, E. J. et al. Biogeochemical processes in canga ecosystems: Armoring of iron ore against erosion and importance in iron duricrust restoration in Brazil. Ore Geol. Rev. 107, 573–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oregeorev.2019.03.013 (2019).

Parker, C. W. et al. Enhanced terrestrial Fe(II) mobilization identified through a novel mechanism of microbially driven cave formation in Fe(III)-rich rocks. Sci. Rep. 12, 17062. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-21365-3 (2022).

Calapa, K. A. et al. Hydrologic alteration and enhanced Microbial Reductive Dissolution of Fe(III) (hydr)oxides under Flow conditions in Fe(III)-Rich rocks: Contribution to Cave-forming processes. Front. Microbiol. 12, 696534. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.696534 (2021).

Dias, J. C., d., S. & Bacellar, L. d. A. P. A hydrogeological conceptual model for the groundwater dynamics in the ferricretes of Capão Xavier, Iron Quadrangle, Southeastern Brazil. Catena. 207, 105663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2021.105663 (2021).

Parker, C. W., Wolf, J. A., Auler, A. S., Barton, H. A. & Senko, J. M. Microbial reducibility of Fe(III) phases associated with the genesis of iron ore caves in the Iron Quadrangle, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Minerals 3, 395–411 (2013). https://doi.org/10.3390/min3040395

López, H. & Oromí, P. A pitfall trap for sampling the mesovoid shallow substratum (MSS) fauna. Speleobiology Notes. 2, 7–11 (2010).

R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Austria, Vienna, (2023).

Chao, A. et al. Rarefaction and extrapolation with Hill numbers: a framework for sampling and estimation in species diversity studies. Ecol. Monogr. 84, 45–67. https://doi.org/10.1890/13-0133.1 (2014).

Hill, M. Diversity and evenness: a unifying notation and its consequences. Ecology. 54, 427–432. https://doi.org/10.2307/1934352 (1973).

Hsieh, T. C., Ma, K. H., Chao, A. & McInerny, G. iNEXT: an R package for rarefaction and extrapolation of species diversity (Hill numbers). Methods Ecol. Evol. 7, 1451–1456. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210x.12613 (2016).

Legendre, P. Interpreting the replacement and richness difference components of beta diversity. Glob Ecol. Biogeogr. 23, 1324–1334. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12207 (2014).

Package. ‘BAT’: Biodiversity Assessment Tools (R package version 2.1.0. (2020). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=BAT.

Mantel, N. & Valand, R. S. A technique of nonparametric multivariate analysis. Biometrics. 26, 547–558 (1970).

Vegan. community ecology package (R package version 2.5-6. (2019). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan.

Deharveng, L. et al. A hotspot of subterranean biodiversity on the brink: Mo so Cave and the Hon Chong Karst of Vietnam. Diversity. 15, 1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15101058 (2023).

Deharveng, L., Bedos, A., Pipan, T. & Culver, D. C. Global subterranean biodiversity: a unique pattern. Diversity. 16, 157 (2024).

Whittaker, R. J. & Triantis, K. A. The species–area relationship: an exploration of that ‘most general, yet protean pattern’. J. Biogeogr. 39, 623–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2012.02692.x (2012).

Leibold, M. A. & Chase, J. M. Metacommunity Ecology504 (Princeton University Press, 2018).

Mammola, S. et al. Ecology and sampling techniques of an understudied subterranean habitat: the Milieu Souterrain Superficiel (MSS). Sci. Nat. 103, 88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-016-1413-9 (2016).

Rendoš, M., Mock, A. & Jászay, T. Spatial and temporal dynamics of invertebrates dwelling karstic mesovoid shallow substratum of Sivec National Nature Reserve (Slovakia), with emphasis on Coleoptera. Biologia. 67, 1143–1151. https://doi.org/10.2478/s11756-012-0113-y (2012).

Berg, M. P., Kniese, J. P., Bedaux, J. J. M. & Verhoef, H. A. Dynamics and stratification of functional groups of micro- and mesoarthropods in the organic layer of a scots pine forest. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 26, 268–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s003740050378 (1998).

Culver, D. C. & Pipan, T. The Biology of Caves and Other Subterranean Habitats (Oxford University Press, 2009).

Gers, C. Diversity of energy fluxes and interactions between arthropod communities: from soil to cave. Acta Oecol. 19, 205–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1146-609X(98)80025-8 (1998).

Nitzu, E. et al. Scree habitats: ecological function, species conservation and spatial-temporal variation in the arthropod community. Syst. Biodivers. 12, 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2013.878766 (2014).

Nae, A. Data concerning the Araneae fauna from the Aninei Mountains karstic area (Banat, Romania). Trav Inst. Speol E Racovitza. 47, 53–63 (2008).

Di Russo, C., Carchini, G., Rampini, M., Lucarelli, M. & Sbordoni, V. Long term stability of a terrestrial cave community. Int. J. Speleol. 26, 75–88. https://doi.org/10.5038/1827-806X.26.1.7 (1997).

Mammola, S. et al. Climate change going deep: the effects of global climatic alterations on cave ecosystems. Anthropocene Rev. 6, 98–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053019619851594 (2019).

Gallão, J. E. & Bichuette, M. E. Brazilian obligatory subterranean fauna and threats to the hypogean environment. ZooKeys. 746, 1–23 (2018).

Brescovit, A. D., Ferreira, R. L., Souza-Silva, M. & Rheims, C. A. Brasilomma gen. nov., a new prodidomid genus from Brazil (Araneae, Prodidomidae). Zootaxa. 3572, 23–32. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3572.1.4 (2012).

Prado, G. C. & Ferreira, R. L. Three new troglobitic species of Pseudochthonius Balzan, 1892 (Pseudoscorpiones, Chthoniidae) from northeastern Brazil. Zootaxa. 5249, 92–110. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.5249.1.5 (2023).

Von Schimonsky, D. M., Gallão, J. E. & Bichuette, M. E. A new troglobitic Pseudochthonius (Pseudoscorpiones: Chthoniidae) from Minas Gerais State, south-east Brazil. Arachnology. 19, 38–46. https://doi.org/10.13156/arac.2022.19.1.38 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Anglo American, Vallourec Mineração, and Gerdau. We thank the staff at Carste Ciência Ambiental for support during different stages of the project. We appreciated the help of Adalberto Santos, Almir Pepato, Camille Sorbo Fernandes, Christie Morais, Douglas Zeppelini, Francisco Castro, Igor Cizauskas, Jéssica Gallo, Kassileny Rocha, Kelly Paixão, Laila Heringer, Luciane Pereira, Luiz Ricardo de Simone, Marcel Araújo, Nathalie Sanchez, Raphael Caetano, Renata Andrade, and Silvana Vargas do Amaral in identifying part of the collected material.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.M.S.M.D. and A.S.A. designed the study. L.M.S.M.D., P.G.d.S., and A.S.A. wrote the main manuscript text. L.M.S.M.D. compiled and organized the data. P.G.d.S. ran the analyzes and prepared the figures and tables of results. D.C. and T.P. contributed to the manuscript writing. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dornellas, L.M.S.M., da Silva, P.G., Auler, A.S. et al. Subterranean fauna associated with mesovoid shallow substratum in canga formations from southeastern Brazil: invertebrate biodiversity of a highly threatened ecosystem. Sci Rep 14, 23211 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75053-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75053-5