Abstract

The Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) one of the important food borne pathogen from milk, which was investigated in this study. The isolates were screened for antimicrobial resistance, enterotoxin genes, biofilm formation, spa typing, coagulase gene polymorphism and accessory gene regulator types. The prevalence of S. aureus in milk samples was 34.4% (89/259). Methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA) was found at 27% (24/89) of the isolates, were classified as community acquired based on SCCmec typing. The 24.71% (22/89) isolates demonstrated multiple antimicrobial resistance (MAR) pattern. However, none of the isolates carried vancomycin and mupirocin resistance genes. The isolates were positive for sea and sed enterotoxin genes and exhibited high frequency of biofilm formation. The High-Resolution Melting and conventional spa typing revealed that the isolates had both animal and community-associated S. aureus clustered origins. Coagulase gene polymorphism and agr typing demonstrated variable genotypic patterns. The finding of this study establishes the prevalence of community associated, enterotoxigenic, biofilm forming and antimicrobial resistance among S. aureus from milk in Chennai city. This emphasizing a potential threat to public health which needs a continuous monitoring system and strategies to mitigate their spread across the food chain and achieve food safety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is an important food-borne pathogen globally, capable of causing staphylococcal food poisoning through ingestion of one or more preformed staphylococcal enterotoxins (SEs), they also capable of producing virulence factors, biofilm formation and acquiring antimicrobial resistance1. There are five classical enterotoxins (SEA, SEB, SEC, SED, and SEE), produced by S. aureus which considered are as main cause of staphylococcal food-poisoning (SFP)2. The staphylococcal protein A (spa) typing technique is based on the repeat sequence of a polymorphic VNTR in the 3′ coding region of the spa protein, which is unique and S. aureus specific. This unique repeat succession in the polymorphic VNTR (variable number tandem repeat), which is a DNA sequence motif that is repeated multiple times in a genome for a given strain/isolate to determines its spa type3. The accessory gene regulatory (agr) quorum sensing system, in which agr gene polymorphism or allelic forms system, acts as one of the major regulatory and control factors for expression of virulence genes and biofilm formation. The agr operon genes regulate over 70 genes in S. aureus, out of which 23 genes control pathogenicity and invasive infections4. S. aureus is mainly divided into four different groups (agr I, agr II, agr III, and agr IV) according to their sequences of agrC (auto inducing peptide) and agrD (cyclic AIP) genes. The different agr types/groups often contribute to pathogenic properties and prevalence specific to geographical areas5.

The Staphylococcus aureus is a highly adaptable bacterium, which has ability to form a complex extracellular polymeric biofilm structure that protects the pathogen against hostile conditions. Biofilms protect the bacterial community against sanitation procedures, environmental stress, host defense and antimicrobial treatment, which leads to persistent contamination or infection among clinical and environmental strains6. The increasing tolerance to antimicrobial drugs by S. aureus has contributed to the emergence and rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) levels, leading to increased morbidity and mortality in human and animal populations7. The study of meta-analysis on the prevalence of MRSA in India was reported using 17,525 various samples of 98 studies was 37% (95% CI 32–41) between 2015–20208. The origin of MRSA could be from human, community, or animal origin and its origin is commonly classified by the presence of the type of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) present in these isolates9.

To better understand and mitigate S. aureus, a pathogen of public health concern, studying the prevalence, toxin-mediated virulence factors, biofilm forming ability, genetic relatedness and antimicrobial resistance patterns in any study area is crucial10. Hence, the present study was conducted to screen S. aureus isolates obtained from milk samples in Chennai city, Tamil Nadu, India for the presence of enterotoxin genes, biofilm forming ability, antimicrobial profiling, spa typing, coagulase gene polymorphism and accessory gene regulator typing.

Results and discussion

A total of 89 confirmed positive S. aureus isolates out of 259 samples (89/259: 34.4%) (34.4 ± 0.609; 95% CI) were used for the present study11. The detailed report on prevalence rate and the odds ratio are outlined in the supplementary Table 2.

Staphylococcal protein A typing (Spa typing) – conventional method and High-resolution melting curve (HRM) analysis

The Staphylococcal protein A is one of the important virulence factors of S. aureus. In the present study, we reported 4 established spa types and the most prevalent spa type was t6296, accounting for 33.7% (30/89) (33.7 ± 1.039; 95% CI). Other spa types found were t267 (23/89) (25.84 ± 1.039; 95% CI), t605(18/89) (20.22 ± 1.039; 95% CI), and t1200(7/89) (7.86 ± 1.039; 95% CI). Eleven isolates had multiple bands and were not characterized into any spa types. The prevalence of spa types and origin of source are given in Table 1. There was no association between the source of milk and occurrence of spa types (p = 0.285). Silva12 reported that when methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) isolates were subjected to spa typing, spa types t605 (37.5%) and t127 (44.6%) were the most predominant types from bovine sources. The spa type t605 was reported to be common in animal origin isolates by various research workers around the globe13. Mitra14 documented that spa type t267 and t1200 are S. aureus clonal ancestors of bovine subclinical mastitis in India. In addition, spa type t267 was noticed from various sources, namely mastitis in cows15; nosocomial and hospital acquired, hospital16; and cross fit facilities17. Similarly, t605 was reported in nosocomial and hospital acquired18; milk and meat19. Another spa type, t6296, was reported from animal origins, as well as community associated S. aureus infection. Our study identified the occurrence of various spa types from milk in the study area, emphasizing non clonality and the dissemination of S. aureus among various sources. The presence of the same spa types in different study areas indicates their transmissibility, clonal expansion, and a need to understand the significance of this in the pathogenic role of these circulating strains. Further, they may also carry virulence and antibiotic resistance genes contributing to persistent colonization with serious public health risks.

Molecular typing methods for epidemiological investigations are easy to perform, highly reproducible, inexpensive, rapid, and easy to interpret20,21. One such technique is HRM analysis, a simpler, less expensive, and faster technique compared to conventional DNA-based sequencing analysis for spa typing20,21. The HRM analysis is based on identification of specific Tm (melting temperature) and shape of melting curve. The distinction of specific Tm could be due to the GC content and amplicon size in the spa types20,21. In the present study, the observed spa types based on sequencing analysis were subjected to HRM analysis using RT-PCR were distinguished based on respective Tm values. HRM analysis showed respective Tm for each of the spa type viz., t605-78.91 °C; t267-79.31 °C; t6296–79.85 °C; t1200-80.34 °C (Supplementary data Fig. 1 showed the melting curve). Various researchers have reported the differentiation of spa types using HRM analysis, but based on our knowledge and literature survey, it is the first of its kind to employ the differentiation of spa types using HRM analysis for milk sample (foods of animal origin). Our study indicated that utilization of HRM analysis will be an alternative for conservative sequence-based spa typing, but further studies are needed to standardize this protocol through spiking studies and testing unknown samples subjected to spa typing.

Coagulase gene polymorphism with RFLP digestion pattern

The coagulase gene-based characterization of S. aureus isolates has been considered a simple and efficient method for molecular typing22. Raimundo23 reported that this technique could be used in epidemiological investigations of S. aureus isolates of bovine mastitis due to its high reproducibility and good discriminatory power. The Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) is a molecular marker technique that detects differences in DNA sequences at specific recognized variation results in different sized DNA fragments produced by digesting the DNA with a restriction enzyme. It is the easiest way to analyze coa gene polymorphism among a large number of bacterial isolates, generating distinct multiple polymorphism patterns. In the present study, coagulase gene polymorphism was elucidated by the PCR assay with milk S. aureus isolates and showed 11 different types of amplicons, including 420 bp, 650 bp, 731 bp, 812 bp, 891 bp, 972 bp, 1070 bp, 1070 bp + 972 bp, 650 bp + 972 bp, 731 bp + 972 bp, 812 bp + 972 bp, and few unspecific bands. The 972 bp coagulase amplicon was observed among 38.2% (34/89) which was the predominant type. The multiple coa patterns obtained in our study signifies considerable variation among the S. aureus types, a finding consistent with other studies22,23,24,25,26. Schlegelova24 reported 10 different genotypes with PCR amplicons sizes varying from 650 bp, 730 bp, 810 bp, and 1050 bp in milk and human origin S. aureus isolates. Sharma25 reported 9 types of coa patterns ranging from 730 to 1130 bp from milk samples in Rajasthan. A double band for coa was also visualized among few isolates, indicating the existence of distinct allelic forms of coa gene. The multiple bands and distinct coa gene pattern are linked to the production of more than one immunologic form of the coagulase protein by some S. aureus isolates26. The PCR amplification products subjected to digestion with a restriction enzyme such as, AluI, HaeIII or NdeI are considered a simple, rapid, and accurate typing method for S. aureus characterization26. In the present study, PCR–RFLP studies with HaeIII restriction enzymes documented 10 different patterns with milk isolates. Of which, these 3 PCR–RFLP patterns viz., 145 bp + 307 bp (27%; 24/89), 226 bp + 307 bp (18%; 16/89), and 145 bp + 307 bp + 469 bp (16%; 14/89), constitute major portion respectively. Our study highlighted the 11 different types of coagulase gene PCR products and 10 different RFLP pattern among S. aureus milk isolates, indicative of genotypic variability. In the present study, the occurrence of coa gene pattern highly varied but overlapped between the sources of origin, hence we could conclude that the high genetic variation but similarity among the isolates is concurrent with the results of our earlier spa typing. The coa gene PCR and PCR–RFLP results matched with spa typing data, which proves that these techniques will be of immense help to identify epidemiological patterns in the event of disease outbreaks with limited laboratory facilities.

Biofilm forming ability of S. aureus

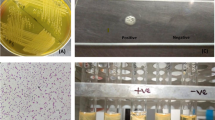

The slime layer (SL) is pseudo-capsule formed by staphylococci, which is primarily composed of polysaccharides27. The formation of black color colonies on Congo red agar (CRA) medium is proportional to slime layer production, predisposing S. aureus to produce biofilm, and Congo red agar has the potential to differentiate polysaccharide intracellular adhesin positive and negative strains27. The complete biofilm formation results are presented in Fig. 1. Congo red agar (CRA) method with milk isolates showed that 68/89 (76.4%) were intense blackish colour (+ +), 14/89 (15.73%) were blackish colour ( +), with overall positivity of 82/89 (92.13%) and 7/89 (7.86%) were red colour (-) negative. Similar to our results, Aslantas and Demir28 investigated 112 S. aureus isolates with Congo red agar method and found 43 (38.4%) as strong, 36 (32.1%) as moderate, 0 as weak, and 33 (29.5%) as negative, with an overall positivity of 79 (70.5%) isolates based on intensity of discoloration in Congo red plates.

The Standard tube adherence method (STA) is a semi-quantitative method that is based on the thickness of biofilm layer formation. STA with our milk isolates found that 21/89 (23.59%) were moderate (+ +), 59/89 (66.29%) were weak ( +), with overall positivity of 80/89 (89.88%) and 9/89 (10.11%) were ( −) negative. Aslantas and Demir28 performed standard tube method to identify biofilm producers and categorized the isolates into strong, moderate, and weak, with an overall positivity of 62.5% based on the strength of staining of tubes. Microtiter plate method is a quantitative method that is based on the opacity of biofilm layer with dye using 96 well polystyrene plates. The Microtiter plate method with milk isolates, identified 7/89 (7.86%) as strong ≥ 0.3 (+ + +), 18/89 (20.22%) as moderate 0.2–0.3 (+ +), 58/89 (65.16%) as weak 0.2–0.1 ( +), with overall positivity of 83/89 (93.25%) and 6/89 (6.74%) as ( −) negative ≤ 0.1 for in-vitro biofilm production. Microtiter plate method was also used by many researchers to evaluate the biofilm formation ability of isolates obtained from human infections and medical devices with varying success29. Upon comparison of all three phenotypic methods for biofilm production, it was observed that around 90% of the isolates have the potential to form biofilms, which may be a serious concern due to potential survive in harsh habitat and spread microbes.

Intercellular adhesion genes [ica(A) and ica(D)] play a major role in biofilm formation in S. aureus. In the present study, we found that 43.82% (39/89) of the milk isolates harbored ica(A) and 98.87% (88/89) of the milk isolates harbored ica(D) genes, respectively. The results of biofilm representing genes are represented in Fig. 2. Vasudevan30 reported 100% prevalence of intercellular adhesion genes, namely ica(A) and ica(D) in milk isolates. The importance of intercellular adhesion genes [ica(AD)] in biofilm production was documented in S. aureus recovered from human medical devices31. The study carried out by Liberto32 established 79.3% concordance between the slime production and presence of ica(A) and ica(D) with biofilm production in S. aureus. The variation between the results of phenotypic and genotypic methods that was observed in our study may be postulated to various reasons, such as point mutations in the ica locus, presence and expression of genes, regulation by agr quorum sensing, or other unknown factors that negatively affects biofilm synthesis, and the same have also been endorsed by other workers33.

The biofilm forming ability of S. aureus in milk samples was analyzed for each biofilm formation detection method using the cumulative logit linear model, with the fixed effect being the sample source. Model goodness of fit was validated via., the ratio of deviance-to-degrees-of-freedom (all close to 1; results not shown). The association between biofilm forming ability and ica(A) prevalence was measured using the Kendall’s Tau-b and Stuart’s Tau-a (Supplementary data 3). The observed values between 0.3–0.6 are considered as moderate-to-strong association. The association between the source and with CRA (p = 0.5782) similarly with STA (p = 0.0377), and with microtiter (p = 0.5257) (Supplementary data 4), denoting those differences among sources with respect to biofilm forming ability irrespective of the biofilm method. Specifically, retail outlet milk had higher biofilm forming ability than dairy farm milk.

Enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus aureus

Staphylococcal enterotoxins (SEs) are exotoxins produced by S. aureus during exponential growth or during the transition from exponential to stationary growth phase of the bacteria34. In the present study, the presence of five classical enterotoxin genes (sea, seb, sec, sed and see) were screened and it was found that there was a prevalence of sea 5.6% (5/89) and sed at 3.4% (3/89) enterotoxin genes. Further, out of 5 isolates with sea enterotoxin gene, there were 2 isolates from dairy farms with spa type t267/agr-2&3/MRSA/SCC-5; t267/agr-1; 2 isolates from retail outlets with spa type t605/agr-3 and t1200/agr-1&3; and 1 isolate from local vendors with spa type t605/agr-3. Similarly, out of 3 positive sed isolates with sea positive enterotoxin gene, there were 2 isolates from local vendors with spa types t1200/agr-1/MRSA/SCC-5; t6296/agr-1; and 1 isolate from retail outlets with spa type t605/agr-1. Fursova35 profiled the enterotoxins of S. aureus as sea, 53.3%; seb, 3.3%; sec, 50%; sed, 4%; and see, 46.6%, 1.6% from cow milk collected from various farms settings in Central Russia. Sharma25 reported that milk isolates from Rajasthan were positive by 30% for sec, 10% for sea, and 3.3% for seb. The positive reports from various countries on enterotoxin in milk and dairy products was 24.6% in Algeria36, 37.1% in China37. The PCR based methods detect genes encoding enterotoxins has two major limitations: staphylococcal strains must be isolated from food, and the presence or absence of genes encoding SEs do not provide any information on the expression of these genes in food systems and on a few occasions encoded by enterotoxin genes carried either in prophage or plasmids38. The present study recorded lower presence of enterotoxigenic strains in S. aureus isolates from the study area, which may be attributed to switching off and switching on enterotoxin genes, as they are present in mobile elements and are extra chromosomal in nature.

Accessory gene regulator (agr gene) typing

In the present study, agr gene polymorphism in milk isolates showed that agr type 1 is the most predominant type found in 79% (70/89) of the isolates, followed by agr type 3 in 8.98% (8/89), agr type 1&2 in 4.49% (4/89), agr type 1&3 in 2.24% (2/89), and agr type 2&3 in 4.49% (4/89). None of the milk isolates harboured agr type 4. Similar to our findings, other researchers have documented agr type 1 as the predominant type in food systems and clinical isolates39. The agr type 3 is the second most common type, which agrees with the present results40,41. As documented by various researchers regarding the absence of agr type 4, our results also documented the absence of agr type 440. The S. aureus isolates with agr group 1 have the ability to establish strong and moderately attached biofilms, as well as weakly adherent biofilms39. Further, Fabres-Klein39 reported biofilm production by bovine S. aureus isolates belonging to agr group 3. Similarly, Vergara40 showed that the majority of isolates with agr 3 are moderate or weak biofilm formers. This indicates that milk isolates with agr 1 are potential biofilm producers, and there is a need to have a better understanding of their pathogenic potential. The accessory gene regulator (agr) controls the expression of many virulence factors, including toxins and exoenzymes41. In the current study, it was observed that the majority of S. aureus isolates harbored the agr type 1 gene, indicating the potential of these isolates to produce a variety of virulence factors, thus posing a significant public health risk.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of S. aureus isolates

A total of 24.71% (22/89) isolates expressed multidrug resistance patterns, which had documented by the calculative index which was calculated by dividing no of antimicrobials tested positive by total antimicrobials tested which when has score more than 0.2 was characterised as multiple antimicrobial resistance (MAR) index. Notably, none of the isolates displayed vancomycin and mupirocin resistance genes (Fig. 3). The presence of methicillin Resistance (MRSA) among the S. aureus isolates from milk samples was documented at 27% (24/89). The results obtained by PCR targeting the mec(A) gene encoding for methicillin resistance corroborate with those obtained by disk diffusion test. Conversely, none of isolates showed positivity for the mec(C) gene in the PCR study. The phenotypic and genotypic identification methods for detecting MRSA were found to be in agreement. There was no evident association between the source and presence of mec(A) gene (p = 0.713).

The cefoxitin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) results were consistent with the disc diffusion assay outcomes. Sharma25 similarly reported 100% sensitivity and specificity of the cefoxitin disk diffusion method and Oxacillin Ezy MIC method in identifying methicillin resistance. This heightened sensitivity to cefoxitin can be explained by the increased expression of the mec(A)-encoded protein PBP2a, induced by cefoxitin, which in turn triggers the mec(A) gene41. The occurrence of MRSA in this study concurred was in line with various research findings Neeling42 reported 39% in Netharlands; Battisti43 reported 38% in Italy; Antoci44 44% in Italy. In contrast, lower occurrence rates of MRSA was reported by other researchers Vanderhaeghen45 in Belgium (10%); Juhasz-Kaszanyitzky46 in Hungary (7.2%).

In the assessment of Vancomycin resistance in S. aureus (VRSA) through disk diffusion assay and MIC, none of the milk isolates displayed resistance. Literature on MIC values of vancomycin for S. aureus isolated from foods of animal origin is limited. Adhikari47 reported MIC values of vancomycin for S. aureus ranging from 0.016 to 1 μg/mL. Corresponding to the VRSA identification in this study, no isolates exhibited positivity in the MIC study and disk diffusion assay. However, a few isolates demonstrated a resistance pattern closer to vancomycin in the disk diffusion assay.

Mupirocin, a non-systemic antibiotic used commonly against S. aureus in humans and rarely in animals, demonstrated a high degree of activity against all staphylococci, including MRSA48. The development of resistance may be linked to acquisition of resistance from plasmids. However, in this study, no mupirocin resistance was observed in either PCR targeting ileS (MUPA) gene and high-level mupirocin resistance 200 µg disk diffusion assay. It is important to note the possibility of future resistance acquisition through environmental contamination and an evolutionary selection pressure, as a few isolates displayed a reduced zone of inhibition and a fuzzy outer layer, warranting cautious consideration.

Detection of antimicrobial resistance genes

The genotypic characterization of antimicrobial resistance genes in S. aureus isolates authenticates the presence and persistence of resistance patterns, providing insights into dissemination of resistance determinants. In this study, the presence of antimicrobial genes is detailed in Table 2 presenting the resistance rates, odds ratio, and their association with isolate’s source of origin. The majority of our results have a P-value around 1, indicating that the resistance pattern is not significantly affected by the source. However, a few antimicrobials showed a P-value less than 1, suggesting a lower dependence between source and resistance occurrence. The heat map representing data on characterization of 89 S. aureus isolates is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Erythromycin and tylosin belong to the macrolide family. The 13% (12/89) of the isolates showed the positivity for erythromycin disk diffusion method and PCR targeting the erm(B) gene. None of the isolates showed the resistance pattern for tylosin disk (0/89) through disk diffusion method, but PCR targeting the aph(A) gene revealed that 31% (28/89) positive. The association between the source and the presence of erm(B) (p = 0.389) and aph(A) genes (P = 0.755) was not significant. Liu49 reported that 60% of their S. aureus milk isolates harbored erythromycin-resistant genes.

The presence of the blaZ gene, was found among 29% (26/89) of the isolates, whereas 8% (7/89) isolates showed positive for β-lactamase production identified through the penicillin zone-edge test. Kaase50 reported that PCR based blaZ detection is superior when compared to phenotypic assays for penicillinase detection. The streptomycin belongs to the aminoglycoside family, and the positivity rate for streptomycin resistance gene, determined using PCR targeting add(E1) gene, was 18% (16/89). The association between the source and with presence of add(E1) gene (p = 0.749) was not significant. Zehra51 recorded that 32 S. aureus isolates possessed aac(A)-aph(D) gene for gentamicin resistance but were phenotypically sensitive to gentamicin, possibly due to non-expression or varied expression of aac(6')-aph(2'')gene52. The 11% (10/89) isolates showed tetracycline resistance pattern upon disk diffusion method whereas 19% (17/89) isolates positive on PCR against the tet(M) gene for S. aureus isolates. There was no association between the source and with presence of tet(M) gene (p = 0.963). In ready-to-eat foods in Poland, targeting tet(M) gene has been reported by Chajęcka-Wierzchowska53. Emaneini54 reported that a few S. aureus isolates were found to be sensitive to tetracycline phenotypically and were positive for tet gene [tet(M) and tet(K)] by PCR assay.

Results of the present study demonstrated variations between phenotypic (disk diffusion method) and genotypic (detection of antimicrobial gene) methods (Table 2 & Fig. 4), and a direct correlation could not be established (Supplementary Table 5). In our earlier research publication, 28 isolates were categorized as multidrug-resistant by disk diffusion assay, and the study also established that occurrence varied with genetic diversity among the isolates using PFGE and divergence pattern of AMR S. aureus55. This variation may be attributed to non-expression of genes, as they are mostly extra chromosomal in nature. This has also been endorsed in literature by Zehra51. However, the presence of resistant genes is an indication that there is a significant potential for these isolates to become antimicrobial resistant strains when they are exposed to varying environmental conditions.

SCCmec typing (Staphylococcal chromosome cassette methicillin resistance)

SCCmec typing serves as a vital molecular tool for identifying the origins of clonal outbreaks. MRSA strains acquire and integrate a mobile genetic element of 21- to 67-kb size into their genome, known as staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCC mec), housing the methicillin resistance mec(A) gene56. In our study, all the MRSA isolates from different sources were categorized as SCC mec type V, as detailed in Table 2 and illustrated in Fig. 4. SCC mec type V signifies that the isolates are community acquired- methicillin resistant S. aureus. (CA-MRSA). The growing prevalence of these CA-MRSA strains poses a significant threat to public health57. In alignment with our findings on SCCmec occurrence, Basanisi57 reported similar characteristics of MRSA isolated from milk and dairy products in southern Italy, with the majority exhibiting SCC mec type V (92.5%). Boswihi58 reported that isolates from foods of animal origin carried SCCmec-V -ST2816-t605. Based on our SCC mec typing results, we conclude that MRSA isolates in this study were community associated, even though they were isolated from bovine and chicken meat, indicating the potential for spread to both livestock and hospitals.

Conclusions

The presence of S. aureus in milk samples emphasizes the urgent need for stringent hygienic practices throughout the milk production and distribution chains in the studied area. Employing genotyping techniques like spa typing, coagulase gene polymorphism, and agr typing was instrumental in understanding prevalent clonal lineages. These lineages observed across various geographical and source origins, suggest a wide distribution of common strains from both the community and animal sources within the region. The concerning is the combination of antimicrobial resistance, biofilm-producing ability, and enterotoxigenic potential in these isolates, posing a significant threat to food safety. The identification of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in food samples raises alarming concerns regarding public health. Future efforts should intensify monitoring, implement rigorous control measures, and encourage responsible use of antibiotics to mitigate these risks and preserve both food safety and public health.

Materials and methods

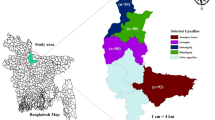

Milk sample collection and isolation of S. aureus

The milk samples for this study were collected from various raw milk retail outlets, vendors, and dairy farms in and around Chennai city, India (13.0827° N, 80.2707° E). A total of 259 raw milk samples were collected for this study, which includes 109 samples collected from 4 small dairy farms, 60 samples from local vendors who sell milk early morning directly to customers and 90 samples from retail outlets who sell milk in sealed packs early morning directly to customers. For each individual sample, 25 ml of milk was collected in a sterile screw cap bottle and immediately transported in a refrigerated chain to the laboratory. Isolation of Staphylococcus aureus was done as per the standard procedure (ISO standard 6888/1:1999 and 6888/2: 1999). In brief, raw milk samples were enriched on brain heart infusion broth (HiMedia, India) with 7% NaCl (sodium chloride) overnight. The selective plating for S. aureus was done on Baird Parker Agar containing potassium tellurite and mannitol salt agar (HiMedia, India). The isolated colonies were Gram stained and subjected to biochemical tests (catalase test, coagulase test, haemolysis test, and HiStaph™ Latex Test Kit; Himedia, India) for initial confirmation. For further confirmation, thermonuclease (nuc) gene PCR assay was performed. Unless otherwise mentioned, the S. aureus strain ATCC 25,923 was used as the reference strain for the entire experiment55.

Staphylococcal protein A typing (spa typing)- conventional method

The polymorphic X-region of the protein A gene (spa) was amplified by PCR using spa-1113F and spa-1514R primers59. The amplified products were sequenced using the Sanger sequencing method (Eurofins, Bengaluru, India). The spa type was detected using a publicly available database (http://spatyper.fortinbras.us/). Furthermore, it was compared and confirmed using the RidomSpaServer (http://www.spaserver.ridom.de/) for the spa repeats succession. The spa types with similar repeat profiles were grouped into a spa complex as described Ruppitsch60.

High Resolution Melting curve (HRM) analysis

The conventional PCR assay primers spa-1113F and spa-1514R were optimized for the Applied Biosystems® Fast7500 (Thermo Fischer Scientific). A total of 20µL reaction contained 10µL Platinum SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix-UDG (2X, Invitrogen Life Technologies), 0.25µL of each primer (0.5 pM stock), 2µL DNA template (20 fg/L) and adjusted with nuclease free water. The amplification conditions and protocol followed was as described by Fasihi20.

Coagulase gene polymorphism

The detection of coagulase gene polymorphism along with RFLP digestion pattern was studied using coagulase (coa) gene primers as described by Himabindu61. The genetic diversity for S. aureus was evaluated based on variation in restriction patterns of coa gene by PCR–RFLP using HaeIII restriction endonuclease (NEB, UK, Ltd).

Detection of enterotoxicity and biofilm forming ability

The genes encoding five classical enterotoxins (sea, seb, sec, sed and see) of S. aureus were investigated as described by Lovseth62. The phenotypic characterization for biofilm formation was performed using Congo red agar28, Standard tube adherence method29, and Microtiter plate method63. The amplification of gene encoding biofilm formation like ica(A) and ica(D) was carried out as outlined by Vasudevan30.

Characterization of accessory gene regulator (agr gene) typing

The accessory gene regulator (agr gene) typing of S. aureus isolates for determination of agr allele types (1–4) using the agr type specific primers and amplification conditions as described by Shopsin64.

Detection of MIC for cefoxitin and vancomycin

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) for S. aureus isolates were determined for cefoxitin (CX) and vancomycin (VAN) by Epsilometer test (E-test) using dual Ezy MIC™ strips (HiMedia, India) (CX 0.5–64 µg/mL) (VAN 0.19–16.0 µg/mL) and the results were interpreted as per the CLSI guidelines65.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The S. aureus isolates were investigated to find the antibiotic susceptibility pattern using commercially available antibiotic discs namely, cefoxitin 30 mg for methicillin resistance, vancomycin 10 µg for vancomycin resistance of S. aureus (VRSA), high-level mupirocin resistance using 200 µg disk, tylosin resistance using 10 µg disk, erythromycin resistance using 15mcg disk, tetracycline resistance using 30 µg disk (HiMedia, India) as per the standard disc diffusion method65.

Detection of antimicrobial resistance genes

Genomic DNA was extracted by QIAamp DNA Kit method (Qiagen’s) from a freshly grown culture in BHI broth as per manufacturer’s instruction. The genotypic characterization of various genes conferring antimicrobial resistance viz., methicillin resistance targeting mec(A), vancomycin resistance with van(A) and van(B), tetracycline resistance with tet(M), penicillin resistance targeting bla(Z), streptomycin resistance with add(E1), erythromycin resistance with erm(B) and tylosin resistance with aph(A) was carried out by conventional PCR (primers details are outlined in Supplementary Table 1).

MRSA- Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec element (SCCmec) typing

Methicillin resistant S. aureus isolates were further characterized for Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec element (SCCmec) typing as described by Zhang66.

Determination of MAR index

The method used for multiple antimicrobial resistance (MAR) index was described earlier by Osundiya67, in brief it’s the number of antimicrobials to which an isolate is resistant (a) is divided by the total number of antimicrobials used in the study (b). [MAR = a/b].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS (version 9.4; Cary, NC) LOGISTIC and FREQ procedures. The S. aureus prevalence in 259 raw milk samples was analyzed using the logit linear model with fixed effects being sample source (dairy farm, local vendor, retail outlet) and milk producer (1, 2, 3, 4) nested within dairy farm. The producer-nested-within-dairy-farm effect was not significant (p = 0.114), hence it was excluded from the subsequent analyses of the 89 milk samples tested positive for S. aureus. The antimicrobial susceptibility of S. aureus in milk samples was analyzed for genotypic characteristic, using the logit linear model with the fixed effect being sample source. Exact inference was applied in the case of sparse (i.e., < 5) resistant or susceptible milk samples. The biofilm forming ability of S. aureus in milk samples was analyzed, for each biofilm formation detection method, using the cumulative logit linear model with the fixed effect being sample source. The effect of milk source on spa type in S. aureus positive samples was evaluated using the exact test using the Pearson Chi-square test statistic for a 2-way contingency table. All tests were performed at the 0.05 level. Pairwise comparison of source effects was carried out based on the 2-sided test for non-zero log odds ratio.

Data availability

“All data generated during this study are included in this article and its Supplementary Information files”.

References

da Silva, A. C., Rodrigues, M. X. & Silva, N. C. C. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in food and the prevalence in Brazil: A review. Braz. J. Microbiol. 51, 347–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42770-019-00168-1 (2020).

Argudín, M. Á., Mendoza, M. C. & Rodicio, M. R. Food poisoning and Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins. Toxins (Basel) 2, 1751–1773. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins2071751 (2010).

Koreen, L. et al. spa typing method for discriminating among Staphylococcus aureus isolates: Implications for use of a single marker to detect genetic micro- and macrovariation. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 792–799. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.42.2.792-799.2004 (2004).

Thompson, T. A. & Brown, P. D. Association between the agr locus and the presence of virulence genes and pathogenesis in Staphylococcus aureus using a Caenorhabditis elegans model. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 54, 72–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2016.11.411 (2017).

Javdan, S., Narimani, T., Shahini Shams Abadi, M. & Gholipour, A. Agr typing of Staphylococcus aureus species isolated from clinical samples in training hospitals of Isfahan and Shahrekord. BMC Res. Notes 12, 363. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-019-4396-8 (2019).

Abdallah, M., Benoliel, C., Drider, D., Dhulster, P. & Chihib, N. E. Biofilm formation and persistence on abiotic surfaces in the context of food and medical environments. Arch. Microbiol. 196, 453–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-014-0983-1 (2014).

Idrees, M., Sawant, S., Karodia, N. & Rahman, A. Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm: Morphology, genetics, pathogenesis and treatment strategies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 7602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147602 (2021).

Patil, S. S. et al. Prevalence of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oman Med. J. 37(4), e440. https://doi.org/10.5001/omj.2022.22 (2022).

Rolo, J. et al. Evidence for the evolutionary steps leading to mecA-mediated β-lactam resistance in staphylococci. PLoS Genet. 13, e1006674. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1006674 (2017).

Qamar, M. U. et al. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria, antimicrobial resistance genes, and antibiotic residue in food from animal sources: One health food safety concern. Microorganisms 11, 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11010161 (2023).

Deepak, S. J. et al. Occurrence of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus from bovine raw milk in Chennai. J. Ani. Res. 10(1), 127–131. https://doi.org/10.30954/2277-940X.01.2020.18 (2020).

Silva, N. C. C. et al. Molecular characterization and clonal diversity of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus in milk of cows with mastitis in Brazil. J. Dairy Sci. 96(11), 6856–6862. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2013-6719 (2013).

Huber, H., Koller, S., Giezendanner, N., Stephan, R. & Zweifel, C. Prevalence and characteristics of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in humans in contact with farm animals, in livestock, and in food of animal origin, Switzerland, 2009. Euro. Surveill. 15, 19542 (2010).

Mitra, S. D. et al. Staphylococcus aureus spa type t267, clonal ancestor of bovine subclinical mastitis in India. J. Appl. Microbiol 114(6), 1604–1615. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.12186 (2013).

Haveri, M., Hovinen, M., Roslöf, A. & Pyörälä, S. Molecular types and genetic profiles of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from bovine intramammary infections and extramammary sites. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46, 3728–3735. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00769-08 (2008).

Harastani, H. H., Araj, G. F. & Tokajian, S. T. Molecular characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from a major hospital in Lebanon. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 19, 33–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2013.10.007 (2014).

Dalman, M. et al. Characterizing the molecular epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus across and within fitness facility types. BMC Infect. Dis. 19, 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3699-7 (2019).

Boswihi, S. S., Udo, E. E. & Al-Sweih, N. Shifts in the clonal distribution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Kuwait hospitals: 1992–2010. PLoS One 11, e0162744. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0162744 (2016).

Sabat, A. J. et al. Overview of molecular typing methods for outbreak detection and epidemiological surveillance. Euro. Surveill. 18, 20380. https://doi.org/10.2807/ese.18.04.20380-en (2013).

Fasihi, Y., Fooladi, S., Mohammadi, M. A., Emaneini, M. & Kalantar-Neyestanaki, D. The spa typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates by High Resolution Melting (HRM) analysis. J. Med. Microbiol. 66, 1335–1337. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.000574 (2017).

Stephens, A. J., Inman-Bamber, J., Giffard, P. M. & Huygens, F. High-resolution melting analysis of the spa repeat region of Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Chem. 54, 432–436. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2007.093658 (2008).

Goh, S. H., Byrne, S. K., Zhang, J. L. & Chow, A. W. Molecular typing of Staphylococcus aureus on the basis of coagulase gene polymorphisms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30, 1642–1645. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.30.7.1642-1645.1992 (1992).

Raimundo, O., Deighton, M., Capstick, J. & Gerraty, N. Molecular typing of Staphylococcus aureus of bovine origin by polymorphisms of the coagulase gene. Vet. Microbiol. 66, 275–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-1135(99)00020-6 (1999).

Schlegelová, J., Dendis, M., Benedík, J., Babák, V. & Rysánek, D. Staphylococcus aureus isolates from dairy cows and humans on a farm differ in coagulase genotype. Vet. Microbiol. 92, 327–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-1135(02)00409-1 (2003).

Sharma, V. et al. Coagulase gene polymorphism, enterotoxigenecity, biofilm production, and antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine raw milk in North West India. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 16, 65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-017-0242-9.PMID:28931414;PMCID:PMC5607506 (2017).

Hookey, J. V., Richardson, J. F. & Cookson, B. D. Molecular typing of Staphylococcus aureus based on PCR restriction fragment length polymorphism and DNA sequence analysis of the coagulase gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36, 1083–1089. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.36.4.1083-1089.1998 (1998).

Heilmann, C. & Götz, F. Further characterization of Staphylococcus epidermidis transposon mutants deficient in primary attachment or intercellular adhesion. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. 287, 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0934-8840(98)80149-7 (1998).

Aslantaş, Ö. & Demir, C. Investigation of the antibiotic resistance and biofilm-forming ability of Staphylococcus aureus from subclinical bovine mastitis cases. J. Dairy Sci. 99, 8607–8613. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2016-11310 (2016).

Mathur, T. et al. Detection of biofilm formation among the clinical isolates of Staphylococci: An evaluation of three different screening methods. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 24, 25–29. https://doi.org/10.4103/0255-0857.19890 (2006).

Vasudevan, P., Nair, M. K., Annamalai, T. & Venkitanarayanan, K. S. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of bovine mastitis isolates of Staphylococcus aureus for biofilm formation. Vet. Microbiol. 92, 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-1135(02)00360-7 (2003).

Yazdani, R. et al. Detection of icaAD gene and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus isolates from wound infections. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 4(18), 1879–1883 (2006).

Liberto, M. C. et al. Phenotypic and genotypic evaluation of slime production by conventional and molecular microbiological techniques. Microbiol. Res. 164, 522–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2007.04.004 (2009).

Cramton, S. E., Gerke, C., Schnell, N. F., Nichols, W. W. & Götz, F. The intercellular adhesion (ica) locus is present in Staphylococcus aureus and is required for biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 67, 5427–5433. https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.67.10.5427-5433.1999.PMID:10496925;PMCID:PMC96900 (1999).

Czop, J. K. & Bergdoll, M. S. Staphylococcal enterotoxin synthesis during the exponential, transitional, and stationary growth phases. Infect. Immun. 9, 229–235. https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.9.2.229-235.1974.PMID:4205941;PMCID:PMC414791 (1974).

Fursova, K. K. et al. Exotoxin diversity of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from milk of cows with subclinical mastitis in Central Russia. J. Dairy Sci. 101, 4325–4331. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2017-14074 (2018).

Titouche, Y. et al. Emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) ST8 in raw milk and traditional dairy products in the Tizi Ouzou area of Algeria. J. Dairy Sci. 102(8), 6876–6884. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2018-16208 (2019).

Cai, H. et al. Prevalence and characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from Kazak cheese in Xinjiang China. Food Control 123, 107759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107759 (2021).

Hennekinne, J. A., De Buyser, M. L. & Dragacci, S. Staphylococcus aureus and its food poisoning toxins: Characterization and outbreak investigation. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36, 815–836. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00311.x (2012).

Fabres-Klein, M. H., Caizer Santos, M. J., Contelli Klein, R., Nunes de Souza, G. & de Oliveira Barros Ribon, A.,. An association between milk and slime increases biofilm production by bovine Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Vet. Res. 11, 3 (2015).

Vergara, A. et al. Biofilm formation and its relationship with the molecular characteristics of food-related methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). J. Food Sci. 82, 2364–2370. https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.13846 (2017).

Skov, R. et al. Evaluation of a cefoxitin 30 microg disc on Iso-Sensitest agar for detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52, 204–207. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkg325 (2003).

de Neeling, A. J. et al. High prevalence of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus in pigs. Vet. Microbiol. 122, 366–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.01.027 (2007).

Battisti, A. et al. Heterogeneity among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from Italian pig finishing holdings. Vet. Microbiol. 142, 361–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.10.008 (2010).

Antoci, E., Pinzone, M. R., Nunnari, G., Stefani, S. & Cacopardo, B. Prevalence and molecular characteristics of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) among subjects working on bovine dairy farms. Infez. Med. 21, 125–129 (2013).

Vanderhaeghen, W. et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) ST398 associated with clinical and subclinical mastitis in Belgian cows. Vet. Microbiol. 144, 166–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.12.044 (2010).

Juhász-Kaszanyitzky, E. et al. MRSA transmission between cows and humans. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13, 630–632. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1304.060833 (2007).

Adhikari, R. et al. Detection of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus and determination of minimum inhibitory concentration of vancomycin for Staphylococcus aureus isolated from pus/wound swab samples of the patients attending a tertiary Care hospital in Kathmandu Nepal. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2017, 2191532. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/2191532 (2017).

Dadashi, M., Hajikhani, B., Darban-Sarokhalil, D., van Belkum, A. & Goudarzi, M. Mupirocin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 20, 238–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgar.2019.07.032 (2020).

Liu, H. et al. Staphylococcus aureus epicutaneous exposure drives skin inflammation via IL-36-mediated T Cell responses. Cell Host Microbe 22, 653-666.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2017.10.006.PMID:29120743;PMCID:PMC5774218 (2017).

Kaase, M. et al. Comparison of phenotypic methods for penicillinase detection in Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14, 614–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.01997.x (2008).

Zehra, R., Kumar, P. K., Sridharan, K. S. & Sekar, U. Nasal carriage of community acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Indian School Children. Int. J. Prev. Med. 5, 1210–1211 (2014).

Martineau, F. et al. Correlation between the resistance genotype determined by multiplex PCR assays and the antibiotic susceptibility patterns of Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44, 231–238. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.44.2.231-238.2000.PMID:10639342;PMCID:PMC89663 (2000).

Chajęcka-Wierzchowska, W., Zadernowska, A., Nalepa, B., Sierpińska, M. & Łaniewska-Trokenheim, Ł. Coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) isolated from ready-to-eat food of animal origin–phenotypic and genotypic antibiotic resistance. Food Microbiol. 46, 222–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fm.2014.08.001 (2015).

Emaneini, M. et al. Distribution of genes encoding tetracycline resistance and aminoglycoside modifying enzymes in Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from a burn center. Ann. Burns Fire Disasters 26, 76–80 (2013).

Deepak, S. J. et al. Prevalence and characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from retail raw milk samples in Chennai India. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 20(12), 570–578. https://doi.org/10.1089/fpd.2023.0050 (2023).

Ito, T. et al. Novel type V staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec driven by a novel cassette chromosome recombinase, ccrC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48, 2637–2651. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.48.7.2637-2651.2004 (2004).

Basanisi, M. G., La Bella, G., Nobili, G., Franconieri, I. & La Salandra, G. Genotyping of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolated from milk and dairy products in South Italy. Food Microbiol. 62, 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fm.2016.10.020 (2017).

Boswihi, S. S. & Udo, E. E. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: An update on the epidemiology, treatment options and infection control. Curr. Med. Res. Pract. 8(1), 18–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmrp.2018.01.001 (2018).

Aires-de-Sousa, M. et al. High interlaboratory reproducibility of DNA sequence-based typing of bacteria in a multicenter study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44, 619–621. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.44.2.619-621.2006 (2006).

Ruppitsch, W. et al. Classifying spa types in complexes improves interpretation of typing results for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44, 2442–2448. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00113-06 (2006).

Himabindu, M., Muthamilselvan, D. S., Bishi, D. K. & Verma, R. S. Molecular analysis of coagulase gene polymorphism in clinical isolates of Methicilin resistant Staphylococcus aureus by restriction fragment length polymorphism based genotyping. Am. J. Infect. Dis. 5, 163–169. https://doi.org/10.3844/ajidsp.2009.163.169 (2009).

Løvseth, A., Loncarevic, S. & Berdal, K. G. Modified multiplex PCR method for detection of pyrogenic exotoxin genes in staphylococcal isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 3869–3872. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.42.8.3869-3872.2004 (2004).

Stepanović, S. et al. Quantification of biofilm in microtiter plates: overview of testing conditions and practical recommendations for assessment of biofilm production by staphylococci. APMIS 115, 891–899. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.apm_630.x (2007).

Shopsin, B. et al. Prevalence of agr specificity groups among Staphylococcus aureus strains colonizing children and their guardians. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41, 456–459. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.41.1.456-459.2003 (2003).

CLSI. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, CLSI approved standard M100-S27. CLSI document, Wayne. (2018). https://file.qums.ac.ir/repository/mmrc/CLSI-2018-M100-S28.pdf

Zhang, K., McClure, J. A., Elsayed, S., Louie, T. & Conly, J. M. Novel multiplex PCR assay for characterization and concomitant subtyping of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec types I to V in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43, 5026–5033. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.43.10.5026-5033.2005 (2005).

Osundiya, O. O., Oladele, R. O. & Oduyebo, O. O. Multiple antibiotic resistance (MAR) indices of Pseudomonas and Klebsiella species isolates in Lagos University Teaching Hospital. African J. Clin. Exp. Microbiol. 14, 164–168 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Chennai, India for providing the facilities for the smooth conduct of the research. This manuscript is part of the PhD thesis submitted by the first author to TANUVAS, Chennai.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

For Conceptualization: P.K, S.J.D, W.R.S, E.A, and S.S,; Formal analysis: S.J.D, P.K, W.R.S, S.K.T.M.A, N.B.R, S.S, Q.K and R.G.A,; Investigation: D.S.J, P.K, E.A, and S.S,; Supervision: P.K, E.A, and S.S,; Writing—original draft: S.J.D, P.K, E.A, and R.G.A,; Writing & reviewing and editing, S.J.D, P.K, N.Q.M, C.A.C and R.G.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no Competing interests

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Deepak, S.J., Kannan, P., Savariraj, W.R. et al. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from milk samples for their virulence, biofilm, and antimicrobial resistance. Sci Rep 14, 25635 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75076-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75076-y