Abstract

Commensal Neisseria (Nc) mainly occupy the oropharynx of humans and animals. These organisms do not typically cause disease; however, they can act as a reservoir for antimicrobial resistance genes that can be acquired by pathogenic Neisseria species. This study characterised the carriage and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of Nc from the oropharynx of 50 participants. Carriage prevalence of Nc species was 86% with 66% of participants colonised with more than one isolate. Isolates were identified by MALDI-ToF and the most common species was N. subflava (61.4%). Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) to penicillin, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, azithromycin, tetracycline, and gentamicin were determined by agar dilution and E-test was used for cefixime. Using Ng CLSI/EUCAST guidelines, Nc resistance rates were above the WHO threshold of 5% resistance in circulating strains for changing the first line treatment empirical antimicrobial: 5% (CLSI) and 13 (EUCAST) for ceftriaxone and 29.3% for azithromycin. Whole genome sequencing of 30 Nc isolates was performed, which identified AMR genes to macrolides and tetracycline. Core gene MLST clustered Nc into three main groups. Gonococcal DNA uptake sequences were identified in two Nc clusters. This suggests that Nc have the potential AMR gene pool and transfer sequences that can result in resistance transfer to pathogenic Neisseria within the nasopharyngeal niche.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neisseria species are gram-negative aerobic cocci, part of the β-proteobacteria class. Neisseria colonise the mucosal surfaces of humans and animals, mainly the oral cavity and nasopharynx. To date, there are at least 43 published Neisseria species by the List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN; accessed 4 May 2024)1 and 47 by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI; accessed 4 May 2024)2. The predicted phylogeny of Neisseria species is continuously evolving. Studies performed using 16s rRNA sequencing and conserved housekeeping genes identified five separate groups of Neisseria3. Group one contained Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Ng), Neisseria meningitidis (Nm), N. polysaccharea, and N. lactamica, group two included N. subflava, N. flavescens, and N. mucosa. The third group included only N. cinerea strains. The fourth and fifth groups contained N. phayngis and N. elongata species respectively3. More recent studies however have suggested the re-classification of certain species into single clusters, for example N. perflava, N. subflava and N. flava are now thought to belong to the N. flavescens group4. Genomic relatedness among Neisseria species has been examined by several methods, but core genome MLST (cgMLST) is now commonly used5,6.

The ability of Neisseria species to uptake DNA and integrate it into their genome is a common feature among the genus leading to a high degree of genetic variation, which is crucial to survival and adaption to their host7. Uptake of DNA in Ng is regulated by the presence of the 10-base pair DNA uptake sequence (DUS) 5’-GCCGTCTGAA-3’8. More recently, a revised 12-base pair sequence was identified (AT-DUS: 5’-AT-GCCGTCTGAA-3’), which enhances transformation efficiency9. A variant DUS (vDUS 5’-GTCGTCTGAA-3’) present in commensal Neisseria (Nc) has also been described, with some species such as N. mucosa having > 3,000 copies10.

Commensal Neisseria are important reservoirs of transferable antimicrobial resistance (AMR) for pathogenic species11,12. The transfer of β-lactam resistance, including extended spectrum cephalosporins (ESC) is of particular importance; Nm and Ng strains resistant to β-lactams have been shown to harbour mosaic penA genes, acquired from Nc species such as N. cinerea and N. perflava13,14. As such, it has been suggested that surveillance of Nc species can contribute to delaying the spread in AMR in pathogenic Neisseria species15.

The prevalence of Nc in the oropharynx and associated AMR is understudied compared to pathogenic Neisseria species. However, Nc prevalence has been estimated between 10.2% and 100%16,17,18,19,20, with some studies reporting individuals’ colonisation by up to four different species17,18,20. Susceptibility of Nc to ceftriaxone is low, with reported median minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of 0.047 mg/L21, 0.002 mg/L22 and 0.03 mg/L23, although the last two studies were limited to only N. lactamica and N. subflava respectively. Additionally, resistance rates to ceftriaxone and cefixime among Nc has been estimated as 28% and 31% respectively17.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report Nc prevalence combined with penicillin, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, azithromycin, tetracycline, and gentamicin MICs and genomic analyses, and the only one to date performed in the United Kingdom. This study highlights that Nc have the potential AMR gene pool and transfer sequences that can result in resistance transfer to Ng and Nm within the nasopharyngeal niche.

Methods

Participant recruitment and sample processing

A cross-sectional study of staff and students from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) was undertaken between June and July 2019. Any participant over the age of 17 years old was eligible for inclusion, with the following exclusion criteria: antibiotic use within one month, usage of antiseptic mouthwash in the past week and participants who are taking steroids or immunosuppressant therapy. The aims of the study were explained to all participants, after which informed consent was obtained. All subsequent experiments were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

A DrySwab device (MWE, Nottingham, UK) was used to sample the peritonsillar areas of participants. Swabs were expressed in 1mL of sterile saline by vortexing vigorously, and 50 µL inoculated onto a Luria-Bertani Vancomycin Trimethoprim Sucrose Neutral Red (LBVT.SNR) agar, as previously described18. Briefly, LBVT.SNR agar consisted of 1% tryptone (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK), 0.5% yeast extract (Oxoid), 0.5% sodium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.), 1.5% Bacteriological Agar Number 1 (Oxoid), 1% w/v sucrose (VWR International, Radnor, Pennsylvania, US), 3 mg/L trimethoprim (Sigma-Aldrich), 3 mg/L vancomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.3% neutral red indicator (Sigma-Aldrich). Inoculated plates were incubated at 5% CO2 at 37oC for 48 h.

Bacterial identification

Cultured isolates were first observed for colonial morphology, including colour, texture, and size. Morphologically distinct colonies from the LBVT.SNR agar were sub-cultured on chocolate agar (Oxoid) for further identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST). Oxidase and gram staining were performed on colonies of interest; oxidase positive, gram-negative cocci were considered as presumptive Neisseria species. Isolates were stored in 20% glycerol brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Oxoid) at -70°C until further testing.

Identification to species level was determined by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionisation – Time-of-Flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-ToF MS), using a Bruker MALDI Biotyper (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, Massachusetts, US). Identification values of 2.0 or over were accepted, while values under 2.0 were repeated once.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Minimum inhibitory concentrations for penicillin, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, azithromycin, tetracycline, and gentamicin (Sigma-Aldrich) were all determined by agar dilution in line with the Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute protocol24, using gonococcal medium base (GCMB) agar (BD Difco, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, US). Cefixime MICs were obtained by E-test (Biomerieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France), on GCMB. Gonococcal WHO controls K, G, V, F, X and Y25 were included in the AST, due to the lack of Nc control strains. Isolates with a penicillin MIC > 1 mg/L were tested for β-lactamase production using a cefinase disk (Oxoid), according to manufacturer’s instructions. As there are no MIC breakpoints for Nc, calculated rates of reduced susceptibility (referred to as resistance for ease) used the Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)24 and European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST v.13.1)26. Gentamicin breakpoints used epidemiological values suggested previously27 (Table 2). Resistance rates to all antimicrobials were calculated for all Nc overall and for each species individually (Table 2).

The MIC values generated were used to deduplicate isolates within individual patients, using the following criteria:

-

(1)

Isolates with the same phenotypic appearance on LBVT.SNR agar, and.

-

(2)

Isolates with same species ID by MALDI-ToF, or whole genome sequencing (WGS) where MALDI did not give an ID, and.

-

(3)

Isolates with at least five out of seven antibiotic matching MICs, within 1 log2 MIC.

Whole genome sequencing and bioinformatic analysis

Total genomic DNA was extracted using the PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit extraction kit (Invitrogen, Waltham, Massachusetts, US) and quantified using the Qubit dsDNA BR assay kit (Invitrogen). The Nextera XT library (2 × 151 bp) prep kit (Illumina, San Diego, California, US) was used to prepare the sequence libraries as per manufacturer’s protocol. The samples were sequenced on a MiSeq System (Illumina) as per the recommended protocol. Additional Illumina (2 × 251 bp) sequencing was performed at MicrobesNG (MicrobesNG, Birmingham, UK). Raw sequence data were quality controlled using Trimmomatic v0.3829 with the following specifications: Leading:3 Trailing:3 SlidingWindow:4:20 Minlen:36. Quality control (QC) checks were performed using FastQC v0.11.830. Fastq reads were mapped against reference sequences using BWA MEM with default settings31 and viewed in Artemis and ACT32,33. De novo sequence assemblies were performed using Spades v3.1334 with default settings, a coverage cut-off of 20 and k-mer lengths of 21, 33, 55, 77, 99 and 111. Draft genome multi-fasta files were evaluated using Quast assessment tool v5.0.235. Contigs were ordered against a N. meningitidis MC58 (accession AE002098) using ABACAS v1.3.1 using -dmbc settings36. Non-matching contigs were appended to the ordered contigs. The resulting assemblies were polished using Pilon v1.22 with default settings37 and annotation using Prokka v1.13 in gram negative mode38.

The assembled contigs were screened for AMR genes using ABRicate39 v1.0.1 and CARD40, and NCBI AMRFinderPlus41 databases and combined. Putative plasmid replicons were identified using the ABRicate with the PlasmidFinder database42. MLST profiles were determined using the software package MLST v2.16.1 from the draft assemblies43. Kraken2 using draft assemblies and the minikraken_8Gb_20200312 database44 was used to predict species. The BSR-Based Allele Calling Algorithm (chewBBACA)45 and predetermined Neisseria schema was used to generate cgMLST profiles and paralog removal using alleles present in 95%46. Allele profile data was used to generate a MSTree in Grapetree using --wgMLST and default settings47. Heatmaps was generated using Morpheus website (software.broadinstitute.org) with hierarchical clustering using Euclidean distance, average linkage method.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with STATA 18 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas, US). Prevalence and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for each of the Nc species. The MICs between Nc species was compared using the Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test. To enable statistical testing, MICs above the maximum or below the minimum range tested were converted to the dilution before or after the limit of detection, as previously described21. For example, azithromycin MIC > 256 mg/L was expressed as 512 mg/L.

Results

Participant demographics and Neisseria isolates

Fifty participants were recruited with 37 (74%) females and median age was 35 (range 17 to 81). The number of participants colonised with Nc was 43/50, generating an estimated population prevalence of 86% (95% CI; 73.8%, 93%). In total, there were 143 morphologically distinct Nc isolates cultured from the 43 participants. A total of 42 isolates were removed as duplicates, leading to a final total of 101 isolates from the 43 participants that grew Nc.

Neisseria species prevalence and characterisation

The most common Nc species detected by MALDI-ToF was N. subflava (62/101, 61.4%) (Supplementary Table S1). The second most prevalent species was N. flavescens (12 isolates, 11.9%), then N. perflava (10, 9.9%), N. macacae (6, 5.9%) and N. mucosa (3, 2.9%) (Supplementary Table S1). Twenty isolates (19.8%) were identified by MALDI-ToF as either one of two probable species, both having an index of over 2.0 (high confidence identification); the isolate with the highest index was considered as the primary ID (Supplementary Table S1). No ID was possible on eight isolates by MALDI-ToF; these were classified as Neisseria spp (Supplementary Table S1).

N. subflava had the highest incidence among the participants, with 74% (37/50 participants) carrying this species. This was followed by N. flavescens (20%, n = 10), N. perflava (18%, n = 9), N. macacae (10%, n = 5) and N. mucosa (6%, n = 3). Ten participants (20%) harboured a single Nc species, however, some participants harboured multiple isolates; 18 (32%) participants were colonised by two isolates, 11 (22%) by three isolates, 2 (4%) by five isolates and 1 (2%) each were colonised by four and eight isolates (Fig. 1).

Susceptibility of commensal Neisseria species

After deduplication of isolates, the following MIC data were analysed: penicillin and ceftriaxone MICs for 101 and 100 isolates respectively and for cefixime, ciprofloxacin, azithromycin, gentamicin and tetracycline, 91 isolates MICs (Table 1). The median MICs for penicillin, ceftriaxone, cefixime, ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, azithromycin and gentamicin were 1 mg/L, 0.06 mg/L, 0.064 mg/L, 0.032 mg/L, 0.5 mg/L, 0.5 mg/L and 4 mg/L respectively (Table 1; Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S2). No isolates produced a detectable β-lactamase. The proportion of isolates overall resistant to penicillin and azithromycin according to both CLSI and EUCAST breakpoints was 26.7% (27/101) and 29.3% (27/92) respectively (Supplementary Table S2). Of the penicillin resistant isolates, 10 were also resistant to azithromycin. N. subflava had the highest number of resistant isolates to both antibiotics (PEN; n = 15/59 [25.4%], AZI; n = 15/58 [25.9%]) (Table 2), with seven isolates being resistant to both antimicrobials. According to CLSI breakpoints, the proportion of isolates resistant to ceftriaxone, cefixime, ciprofloxacin and tetracycline were 5%, 4.3%, 16.3% and 22.8% respectively. The proportion of isolates resistant to these antibiotics differed by EUCAST breakpoints; they were 13.0%, 5.4%, 45.7% and 37%. No isolates were resistant to gentamicin.

The Kruskal-Wallis H was performed only on N. subflava, N. macacae, N. perflava and N. flavescens (Table 1). The test demonstrated no statistically significant difference in MIC values between the four Neisseria species. (Table 1).

Genomic analysis and relatedness

Thirty isolates were selected for whole genome sequencing (WGS), covering isolates with ceftriaxone MICs ≥ 0.125 mg/L (15 isolates) and < 0.125 mg/L (four isolates), at least one of each species from the MALDI-ToF identification (six isolates) and three isolates where MALDI-ToF identification was not possible (Supplementary Table S5). The genomic data from the study isolates, along with 61 Neisseria reference genomes (Supplementary Table S3), was used to generate cgMLST neighbour joining phylogeny.

The 91 Neisseria isolates clustered in approximately five clusters (Fig. 3). As previously described, N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae isolates clustered together with N. lactamica and N. polysaccharea4 however N. bergeri and N. cinerea were also present within the cluster. No study isolates were present in the N. meningitidis/N. gonorrhoeae cluster (Supplementary Tables S3 and S4). The N. bacilliformis group also contained N. bacilliformis, N. animaloris, and 8 other species but no study isolates (Supplementary Table S3 and S4). MLST analysis of N. perflava CCH10-H12, which clustered with N. mucosa isolates only matched 3 alleles in the database: abcZ233, adk178 and pdhC561 (Supplementary Table S3). This combination of alleles was only found together in ST-16,693 but this ST was not associated with any isolates in the database. abcZ233 was present in ST-3706 (N. mucosa), ST-9926 (N. perflava), ST-10,150 (N. mucosa), ST-16,006 (N. mucosa), ST-16,037 (N. mucosa), ST-16,480 (N. mucosa). Adk178 was present in ST-3706 (N. mucosa) and pdhC561 was present in ST-12,049 (N. mucosa).

The N. flavescens cluster contained 3/4 N. flavescens, a single N. subflava and 10 study isolates. The N. subflava cluster contained 4/5 N. subflava and 2/2 N. perflava plus 16 study isolates. Finally, the N. macacae cluster contained 1/1 N. macacae, 3/3 N. elongata, 3/3 N. sicca and 1/1 N. mucosa plus four study isolates (Supplementary Tables S3 and S4).

We compared the first and second species identification given by MALDI-ToF and Kraken2 from the genome sequence, excluding the three isolates with no MALDI-ToF ID. A total of 16/26 (61.5%) isolates had ID concordance between the primary MALDI-ToF ID and Kraken2 and 22/26 (84.6%) had concordance between any MALDI-ToF ID and Kraken2 (Supplementary Table S5). The three isolates with no MALDI-ToF ID were predicted as N. subflava by Kraken2. All isolates identified as N. subflava, N. perflava or N. flavescens by MALDI-ToF were predicted as N. subflava by Kraken2. The isolates identified as N. macacae by MALDI-ToF were predicted as N. mucosa by Kraken2.

Genotypic antimicrobial resistance

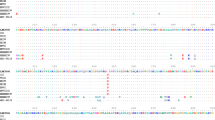

One isolate (49 A) produced a poor assembly so was removed from further analysis. Analysis of the remaining 29 Nc genomes for AMR related genes identified five matches (min 80% identity, 80% coverage) with the CARD database, three with ResFinder, eight with MEGARes additionally 14 virulence related genes with matched against VFDB (Fig. 4).

AMR and virulence genes. Draft genomes were analysed for AMR genes (CARD, ResFinder and Megares databases) and virulence (VFDB) genes using Abricate (min ID/coverage 80%). Circles represent the presence of gene, scaled to %ID. Similar profiles were grouped using Euclidean hierarchical clustering using average linkage algorithm in Morpheus. Study isolates are given with MALDI-ToF identification in parenthesis. 1 to 5 indicate cgMLST clustering group; 1 = N. meningitidis/N. gonorrhoeae cluster, 2 = N. bacilliformis cluster, 3 = N. flavescens cluster, 4 = N. subflava cluster, 5 = N. macacae cluster.

The MacAB-TolC tripartite macrolide efflux complex consists of macA, macB and tolC. macB was present in most isolates except 12/14 of the N. bacilliformis cluster isolates and N. perflava CCH10-H12, however macA was only identified in N. meningitidis/N. gonorrhoeae cluster isolates and N. macacae group isolates plus 49 A48 (Fig. 4). Similarly, mtrC and mtrD, along with mtrE, encode a multidrug efflux complex but while mtrCD were conserved within N. meningitidis/N. gonorrhoeae cluster [cluster 1], these genes differentiated the N. mucosa/sicca/macacae (present) from N. elongata and N. perflava CCH10-H12 (absent) within the N. macacae cluster5. mtrCD was also completely absent from the N. bacilliformis cluster2. Within the N. flavescens and N. subflava cluster all isolates except N. flavescens ERR2764931 had mtrD but only five isolates also had mtrC.

PenA, linked to β-lactam resistance, was only present in the N. meningitidis/N. gonorrhoeae, N. flavescens (except N. flavescens ERR2764931) and N. subflava clusters. TetM, a ribosomal protection protein that confers tetracycline resistance, was present in 7 isolates: N. subflava C2007002879, 1 A, 10 A, 14B, 18B, 35 A and 48B, which were spread evenly across N. flavescens and N. subflava clusters (Fig. 4). Isolates 14B and 18B had tetracycline MICs of 0.5 mg/L and 1 A, 10 A & 35 A had MICs of 16–32 mg/L (Supplementary Table S2). Tetracycline MIC testing was not performed on isolate 48B as it was nonviable on resuscitation.

Capsule polysaccharide modification proteins (LipA/LipB) and capsule polysaccharide export ATP-binding protein (CtrD) were present in all N. meningitidis (except N. meningitidis alpha14) but absent from N. gonorrhoeae and N. lactamica Additionally, all three genes were conserved within the majority of N. flavescens/N. subflava clusters (lipA: 34/36, lipB: 32/36, ctrD: 22/36) but absent from N. bergeri, N. polysaccharea and N. cinerea.

Analysis of DNA transfer mechanisms

The Nc genomes were screened for the presence of gcDUS, AT-DUS and vDUS. All three DUS dialects were found in the Nc genomes. Overall, the N. subflava complex (N. subflava, N. perflava and N. flavescens) isolates had more gcDUS repeats than vDUS whereas the opposite was seen with N. macacae. The N. subflava complex isolates had 2738–2990 Ng DUS, 144–192 AT-DUS and 158–276 vDUS repeats. N. macacae isolates carried 247–292 Ng DUS, 29–40 AT-DUS and 3608–3802 vDUS repeats (Supplementary Table S6). No genetic plasmid markers were identified; however, tetM has previously been identified as plasmid mediated49. Raw reads from all tetM positive isolates were mapped against pEP5289 (GU479466, ‘Dutch’ tetM) and pEP5050 (GU479464, ‘American’ tetM genetic load area) which showed no mapped reads except to the tetM gene. Subsequent analysis identified a cryptic 40 kb plasmid in isolate 8 A (N. macacae) that had 95% coverage, 99.7% identity to a Ng plasmid (CP048906) however this plasmid did not contain any AMR genes.

Discussion

The value of monitoring carriage and the AMR reservoir of Nc from the human oropharynx is becoming increasingly evident, not only to prevent the development of AMR in Nm and Ng, but also the assess the risk of oropharyngeal colonisation and persistence of the pathogenic Neisseria species. Not only is there transmission of AMR genes between Neisseria species, there is also evidence Nc are shared between intimate partners50, further exacerbating the problem of AMR transmission. In this study we characterised the carriage, genomic relatedness and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of Nc species, acquired from the oropharynx of 50 LSHTM volunteers.

In this study, 84% of the study population were colonised with at least one Nc species. This finding aligns with recent studies reporting Nc carriage of 68%21 and 100%17. However, our findings contrasted with those found by Diallo et al.16 and Le Saux et al.19 who found a Nc prevalence of 10.2% and 11.6% respectively. These studies were focused on colonisation of Nm and in particular vaccinated individuals, and it has been suggested that both Nm and Nc carriage can be negatively associated with recent meningococcal vaccination16. Also, both these studies used Theyer-Martin (TM) media for pathogenic Neisseria species, whereas some Nc species such as N. cinerea, N. subflava and N. mucosa do not grow very well on this media51. This was confirmed by the lack of growth of study Nc on Ng selective VCAT agar. LBVT.SNR media, formulated specifically for the isolation of Nc18, aligns with two older studies that used the same media and identified high prevalence of 96.6%18 and 100%20. Additionally, the study by Sáez et al. that found 100% prevalence used both LBVT.SNR and TM media, the latter added specifically to ensure the recovery of Nm and Nl20.

The most common Nc species found in this study was N. subflava, with 61.4% and 74% of participants colonised by this species. The colonisation rate of N. subflava is similar found in two recent studies17,21, especially when combined with N. flavescens and N. perflava as previously described4. Surprisingly, N. lactamica were not isolated from the study participants, however this was likely due to omission of selective media for pathogenic Neisseria species. In fact, as part of our quality control checks, a N. lactamica laboratory reference strain grew very poorly on SBVT.SNR media. Carriage of N. lactamica seems to be variable depending on the population; the prevalence of N. lactamica in previous studies ranged from 0.4%17 to 17.3%52. Interestingly, some studies showed that young children carry N. lactamica at much higher rates than adults16,52, which could further explain the lack of recover in our study.

Concordance between MALDI-ToF species identification and Kraken2 prediction was just 65.2% when considering the primary species ID. This further demonstrates the challenge of accurate identification in this homogeneous genus, due to the limitations of both technologies. The accuracy of these techniques is only as good as the curation of the database itself demonstrated by several reports of misidentification of Nc by MALDI-ToF53,54,55. Similarly, genomic identification is limited by the high genetic recombination of Neisseria species6,28,56,57,58 coupled with the lack of an internationally accepted genomic identification scheme.

The introduction of more advanced techniques such as WGS, rMLST and cgMLST have led to several re-classifications of existing species and the discovery of novel species4,5,6. In this study, the isolates clustered into three distinct groups, the N. flavescens, N. perflava and N. macacae clusters, in line with previous findings. The clustering agreed with previously suggested re-classifications of N. perflava and N. subflava into different variants of N. subflava5. Similarly, it has been suggested that N. macacae and N. mucosa can be merged into a single N. mucosa group59, which our cgMLST cluster analysis supports.

Resistance to all antimicrobials except gentamicin and cefixime was high according to both CLSI and EUCAST breakpoints. The median MIC to ceftriaxone was 0.06 mg/L, which although phenotypically susceptible according to both CLSI and EUCAST breakpoints is just 1–2 log2 MIC lower than the 0.125–0.25 mg/L breakpoint with one isolate having an MIC of 8 mg/L. This translates to resistance rates of 5% (CLSI) and 13% (EUCAST) compared to Ng resistance rates of 0% for the same year in England28, but lower than Nc resistance rates of 28% reported in Vietnam17. Differing AMR rates could be due to differences in study populatons, as the study in Vietnam included only men who have sex with men (MSM)17. This patient group are described as having a higher likelihood of repeated gonococcal infection and exposure to ceftriaxone, leading to AMR selection pressures on Nc17.

Commensal Neisseria species with high ESC MICs pose a significant reservoir for transfer of resistance and development of mosaic genes in pathogenic Neisseria species. Although other antimicrobials are no longer used as empirical treatment, resistance to these should not be overlooked, as there has been evidence of macrolide, tetracycline and fluoroquinolone AMR transfer57. Investigations of the Neisseria resistome have found high resistance to β-lactams, fluoroquinolones encoded by mutations in gyrA, tetracylines due to tetM as well as TEM-type β-lactamases60. Importantly, a recent study demonstrated in vitro transformation of zoliflodacin resistance, a new DNA replication inhibitor evaluated for treatment of Ng, from Nc to Ng, suggesting important implications for the introduction of new antimicrobials61. In this study, 30 Nc isolates genomes were analysed for genotypic markers of acquired resistance and we identified several acquired resistance genes. For example, msr(D) responsible for high level macrolide resistance (> 256 mg/L)57, was present in 2 A which had an MIC of > 256 mg/L. Macrolide resistance has also been associated with overexpression of the MtrCDE efflux pump, which also confers resistance to b-lactams, tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones62. The MtrCDE efflux pump is commonly found in Ng62 and other Neisseria species, however correlation between presence of mtrCDE and any macrolide resistances was not identified. Similarly, most of our Nc isolates had macB, another efflux pump complex also found in Ng63, but there was no correlation with phenotypic resistance. Antimicrobial resistance due to overexpression of efflux pumps are associated with specific mutations64 and the presence of efflux pumps genes do not necessarily translate to phenotypic resistance.

Transfer of AMR genes between isolates provides a rapid solution to antibiotic treatment compared to accumulation of new genes through evolutionary purposes. Nc are proposed as a possible source of horizontally acquired AMR genes in pathogenic Neisseria, for example horizontal gene transfer of penA from N. lactamica, N. macacae, N. mucosa and N. cinerea to Ng58,65,66,67. Neisseria are naturally competent and therefore naked DNA is a primary method of acquiring new DNA. The Neisseria DUS sequences enhance this DNA uptake. Members of the N. subflava and N. flavescens clusters had more copies of gcDUS than vDUS and the opposite was true for the N. macacae cluster (Supplementary Table S6). These findings agree with previous published data10,68 and suggest that DNA incorporation into Ng and Nm would be more efficient from N. subflava and N. flavescens clusters than N. macacae cluster isolates. Even though Nc have fewer copies of AT-DUS that enhances transformation efficiency, these findings demonstrate the high likelihood of HGT between Nc and pathogenic Neisseria species, not just relating to AMR, but also virulence and niche adaptation68. Plasmids also can transfer AMR genes in Neisseria for example tetM was associated with tetracycline resistance in six of our isolates (1 A, 10 A, 14B, 18B, 35 A and 48B), three of which had tetracycline MICs of 16–32 mg/L (1 A, 10 A and 35 A) and two had an MIC of 0.5 mg/L (14B and 18B) (Supplementary Table S2). Tetracycline resistance due to tetM is usually coded on a conjugative plasmid in Ng, resulting in MICs of 16–64 mg/L69. No plasmid markers or known tetM carrying plasmids were detected suggesting tetM may be present in the chromosome of some Nc species. Interestingly, a single plasmid was identified in a N. macacae isolate that had previously been sequenced in a Ng isolate. While this supports transfer between pathogenic and commensal Neisseria no AMR genes were present on this plasmid.

In our study we performed comprehensive phenotypic and genotypic analysis of both Nc carriage, speciation, and AMR determinants, but it is not without limitations. Firstly, our sample size was small, which limited statistical power in some analyses, such as exploring the relationship between Nc and AMR. Additionally, we did not use Ng selective agar, which may have enabled us to recover N. lactamica due to the possibility of isolating Ng/Nm which was outside the scope of the project and had additional ethical considerations. There is currently no gold standard for speciation of Nc; the accuracy of genomic and MALDI-ToF analyses are reliant on the accuracy of published reference genomes and identification databases. The nomenclature and speciation of Nc is evolving, with species reclassified and new species being discovered, meaning that taxonomic errors in reference databases have been discovered59. This issue also extends to phenotypic and genotypic analysis of AMR. Firstly, there are no guidelines or resistance breakpoints for Nc and most published literature have used CLSI or EUCAST breakpoints for Ng. This also means there are no international control strains for Nc susceptibility testing which impacts the accuracy of both phenotypic and genotypic testing. Published fully susceptible Nc reference genomes will enable detection of single nucleotide polymorphisms and mosaic genes as well as acquired resistances.

This study demonstrated high pharyngeal colonisation rates in our population with higher AMR rates than Ng. Although more research in needed to understand the mechanisms of HGT in vivo, monitoring Nc may help us predict the rates of Ng resistant strains occurring in the future, especially relating to ESCs and other newly introduced antimicrobials.

Data availability

The whole genome datasets presented in this study can be found online at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena under study PRJEB67528. Any additional datasets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Parte, A. C., Carbasse, J. S., Meier-Kolthoff, J. P., Reimer, L. C. & Göker, M. List of prokaryotic names with standing in nomenclature (LPSN) moves to the DSMZ. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 70(11), 5607–5612. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijsem.0.004332 (2020).

C. L. Schoch et al., NCBI Taxonomy: A Comprehensive Update on Curation, Resources and Tools (Oxford University Press, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1093/database/baaa062

Smith, N. H., Holmes, E. C., Donovan, G. M., Carpenter, G. A. & Spratt, B. G. Networks and groups within the genus Neisseria: Analysis of argF, recA, rho, and 16S rRNA Sequences from Human Neisseria Species. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16(6), 773–783 (1999).

Bennett, J. S. et al. A genomic approach to bacterial taxonomy: An examination and proposed reclassification of species within the genus Neisseria. Microbiology (United Kingdom) 158(6), 1570–1580. https://doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.056077-0 (2012).

K. Diallo et al. Genomic characterization of novel Neisseria species. Sci. Rep. 9(1), (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50203-2

Maiden, M. C. J. & Harrison, O. B. Population and functional genomics of neisseria revealed with gene-by-gene approaches. J. Clin. Microbiol. 54(8), 1949–1955. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00301-16 (2016).

Hamilton, H. L. & Dillard, J. P. Natural transformation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: From DNA donation to homologous recombination. Mol. Microbiol. 59(2), 376–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04964.x (2006).

Frye, S. A., Nilsen, M., Tønjum, T. & Ambur, O. H. Dialects of the DNA Uptake Sequence in Neisseriaceae. PLoS Genet. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003458 (2013).

Duffin, P. M. & Seifert, H. S. DNA uptake sequence-mediated enhancement of transformation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae is strain dependent. J. Bacteriol. 192(17), 4436–4444. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00442-10 (2010).

Marri, P. R. et al. Genome sequencing reveals widespread virulence gene exchange among human Neisseria species. PLoS One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0011835 (2010).

Hamilton, H. L. and Dillard, J. P. Natural transformation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: From DNA donation to homologous recombination (2006). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04964.x

Higashi, D. L. et al. N. elongata produces type IV pili that mediate interspecies gene transfer with N. gonorrhoeae. PLoS One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0021373 (2011).

Mechergui, A., Touati, A., Baaboura, R., Achour, W. & Ben Hassen, A. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of β-lactams resistance in commensal Neisseria strains isolated from neutropenic patients in Tunisia. Ann. Microbiol. 61(3), 695–697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13213-011-0202-0 (2011).

Igawa, G. et al. Neisseria cinerea with high ceftriaxone MIC is a source of ceftriaxone and cefixime resistance-mediating penA sequences in neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 62(3), e02069-e2117. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC (2018).

Goytia, M. & Wadsworth, C. B. Canary in the coal mine: How resistance surveillance in commensals could help curb the spread of AMR in PATHOGENIC Neisseria. mBio 13(5), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.01991-22 (2022).

Diallo, K. et al. Pharyngeal carriage of Neisseria species in the African meningitis belt. J. Infect. 72(6), 667–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2016.03.010 (2016).

Dong, H. V. et al. decreased cephalosporin susceptibility of oropharyngeal Neisseria species in antibiotic-using men who have sex with men in Hanoi, Vietnam. Clin. Infect. Dis. 70(6), 1169–1175. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciz365 (2020).

Knappl, J. S. & Hook, E. W. Prevalence and persistence of Neisseria cinerea and other Neisseria spp. in adults. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26(5), 896–900. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.26.5.896-900.1988 (1988).

Le Saux, N. et al. Carriage of Neisseria species in communities with different rates of meningococcal disease. Can. J. Infect. Dis. 3(2), 60–64. https://doi.org/10.1155/1992/928727 (1992).

Sâez, J. A., Carmen, N. & Vinde, M. A. Multicolonization of human nasopharynx due to Neisseria spp. Int. Microbiol. 1(1), 59–63 (1998).

Laumen, J. G. E. et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of commensal Neisseria in a general population and men who have sex with men in Belgium. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03995-1 (2022).

Arreaza, L., Salcedo, C., Alcalá, B. & Vasquez, J. What about antibiotic resistance in Neisseria lactamica?. J. Antimicrobial. Chemother. 49, 545–547. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/49.3.545 (2002).

Furuya, R. et al. Antimicrobial resistance in clinical isolates of Neisseria subflava from the oral cavities of a Japanese population. J. Infect. Chemother. 13(5), 302–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10156-007-0541-8 (2007).

Jo-Anne, R. Dillon and Stefania Starnino, Laboratory Manual Identification and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Neisseria gonorrhoeae Second Edition GASP-LAC Co-ordinating Centre, Saskatchewan, 2011.

Unemo, M. et al. The novel 2016 WHO Neisseria gonorrhoeae reference strains for global quality assurance of laboratory investigations: Phenotypic, genetic and reference genome characterization. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71(11), 3096–3108. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkw288 (2016).

The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, “European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters v13.1,” 2023.

Brown, L. B. et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae antimicrobial susceptibility in Lilongwe, Malawi, 2007. Sex Transm. Dis. 37(3), 169–172. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181bf575c (2010).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30(15), 2114–2120. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 (2014).

S. Andrews, “FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data,” Jun. 2015. Available: https://qubeshub.org/resources/fastqc

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 26(5), 589–595. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698 (2010).

Carver, T., Harris, S. R., Berriman, M., Parkhill, J. & McQuillan, J. A. Artemis: An integrated platform for visualization and analysis of high-throughput sequence-based experimental data. Bioinformatics 28(4), 464–469. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr703 (2012).

Carver, T. et al. Artemis and ACT: Viewing, annotating and comparing sequences stored in a relational database. Bioinformatics 24(23), 2672–2676. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btn529 (2008).

Prjibelski, A., Antipov, D., Meleshko, D., Lapidus, A. & Korobeynikov, A. Using SPAdes De Novo Assembler. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 70(1), e102. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpbi.102 (2020).

Mikheenko, A., Prjibelski, A., Saveliev, V., Antipov, D. & Gurevich, A. Versatile genome assembly evaluation with QUAST-LG. Bioinformatics 34(13), i142–i150. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty266 (2018).

Assefa, S., Keane, T. M., Otto, T. D., Newbold, C. & Berriman, M. ABACAS: Algorithm-based automatic contiguation of assembled sequences. Bioinformatics 25(15), 1968–1969. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp347 (2009).

Walker, B. J. et al. Pilon: An integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One 9(11), e112963. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112963 (2014).

Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30(14), 2068–2069. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153 (2014).

Seemann, T. Abricate. Github (accessed 04 September 2023); https://github.com/tseemann/abricate

Jia, B. et al. CARD 2017: Expansion and model-centric curation of the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 45(D1), D566–D573. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw1004 (2017).

Feldgarden, M. et al. Validating the AMRFINder tool and resistance gene database by using antimicrobial resistance genotype-phenotype correlations in a collection of isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 63(11), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00483-19 (2019).

Carattoli, A. et al. In Silico detection and typing of plasmids using plasmidfinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58(7), 3895–3903. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02412-14 (2014).

Seemann, T. MLST. Github (Accessed 04 September 2023); https://github.com/tseemann/mlst

Wood, D. E., Lu, J. & Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 20(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-019-1891-0 (2019).

Silva, M. et al. chewBBACA: A complete suite for gene-by-gene schema creation and strain identification. Microb. Genom. 4(3), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1099/mgen.0.000166 (2018).

Harrison, O. B. et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae population genomics: Use of the gonococcal core genome to improve surveillance of antimicrobial resistance. J. Infect. Dis. 222(11), 1816–1825. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa002 (2020).

Zhou, Z. et al. Grapetree: Visualization of core genomic relationships among 100,000 bacterial pathogens. Genome Res. 28(9), 1395–1404. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.232397.117 (2018).

Greene, N. P., Kaplan, E., Crow, A. & Koronakis, V. “Antibiotic resistance mediated by the MacB ABC transporter family: A structural and functional perspective. Front. Media S.A. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00950 (2018).

Pachulec, E. & van der Does, C. Conjugative plasmids of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. PLoS One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009962 (2010).

Van Dijck, C., Laumen, J. G. E., Manoharan-Basil, S. S. & Kenyon, C. Commensal neisseria are shared between sexual partners: Implications for gonococcal and meningococcal antimicrobial resistance. Pathogens. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9030228 (2020).

Knapp, J. S. Historical perspectives and identification of Neisseria and related species. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1(4), 415–431. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.1.4.415 (1988).

Kristiansen, P. A. et al. Carriage of Neisseria lactamica in 1- to 29-year-old people in Burkina Faso: Epidemiology and molecular characterization. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50(12), 4020–4027. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01717-12 (2012).

Golparian, D., Tabrizi, S. N. & Unemo, M. Analytical specificity and sensitivity of the APTIMA combo 2 and APTIMA GC assays for detection of commensal neisseria species and neisseria gonorrhoeae on the gen-probe panther instrument. Sex Transm. Dis. 40(2), 175–178. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182787e45 (2013).

Kawahara-Matsumizu, M., Yamagishi, Y. & Mikamo, H. Misidentification of Neisseria cinerea as Neisseria meningitidis by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). J. Infect. Dis. 71, 85–87. https://doi.org/10.7883/yoken.JJID.2017.183 (2018).

Morel, F. et al. Use of andromas and bruker MALDI-TOF MS in the identification of Neisseria. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 37(12), 2273–2277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-018-3368-6 (2018).

Alber, D. et al. Genetic diversity of Neisseria lactamica strains from epidemiologically defined carriers. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39(5), 1710–1715. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.39.5.1710-1715.2001 (2001).

de Block, T. et al. Successful intra- but not inter-species recombination of msr(D) in Neisseria subflava. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.855482 (2022).

Khoder, M. et al. Whole genome analyses accurately identify Neisseria spp. and limit taxonomic ambiguity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 13456. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232113456 (2022).

UKHSA, Antimicrobial Resistance in Neisseria Gonorrhoeae in England and Wales Key findings from the Gonococcal Resistance to Antimicrobials Surveillance Programme (GRASP 2020, accessed 16 April 2024, 2021); https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6193dbc78fa8f50382034cf5/GRASP_2020_Report.pdf

Spratt, B. G., Bowler, L. D., Zhang, Q. Y., Zhou, J. & Smith, J. M. Role of interspecies transfer of chromosomal genes in the evolution of penicillin resistance in pathogenic and commensal Neisseria species. J. Mol. Evol. 34(2), 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00182388 (1992).

Lujan, R., Zhang, Q. Y., Saez Nieto, J. A., Jones, D. M. & Spratt, B. G. Penicillin-resistant isolates of Neisseria lactamica produce altered forms of penicillin-binding protein 2 that arose by interspecies horizontal gene transfer. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35(2), 300–304. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.35.2.300 (1991).

Marangoni, A. et al. Mosaic structure of the penA gene in the oropharynx of men who have sex with men negative for gonorrhoea. Int. J. STD AIDS 31(3), 230–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956462419889265 (2020).

Xiu, L. et al. Emergence of ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains harbouring a novel mosaic penA gene in China. J. Antimicrobial. Chemother. 75(4), 907–910. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkz530 (2020).

Fiore, M. A., Raisman, J. C., Wong, N. H., Hudson, A. O. & Wadsworth, C. B. Exploration of the neisseria resistome reveals resistance mechanisms in commensals that may be acquired by N. Gonorrhoeae through horizontal gene transfer. Antibiotics 9(10), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics9100656 (2020).

Abdellati, S. et al. Gonococcal resistance to zoliflodacin could emerge via transformation from commensal Neisseria species. An in-vitro transformation study. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49943-z (2024).

Evert, B. J. et al. Self-inhibitory peptides targeting the Neisseria gonorrhoeae MtrCDE efflux pump increase antibiotic susceptibility. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01542-21 (2022).

Rouquette-Loughlin, C. E., Balthazar, J. T. & Shafer, W. M. Characterization of the MacA-MacB efflux system in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Antimicrobial. Chemother. 56(5), 856–860. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dki333 (2005).

Warner, D. M., Folster, J. P., Shafer, W. M. & Jerse, A. E. Regulation of the MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux-pump system modulates the in vivo fitness of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Infect. Dis. 196(12), 1804–1812. https://doi.org/10.1086/522964 (2007).

Młynarczyk-Bonikowska, B., Kujawa, M., Malejczyk, M., Młynarczyk, G. & Majewski, S. Plasmid-Mediated Resistance to Tetracyclines Among Neisseria Gonorrhoeae Strains Isolated in Poland Between 2012 and 2013 (Termedia Publishing House Ltd., 2016). https://doi.org/10.5114/ada.2016.63887.

Calder, A. et al. Virulence genes and previously unexplored gene clusters in four commensal Neisseria spp. Isolated from the human throat expand the neisserial gene repertoire. Microb. Genom. 6(9), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1099/mgen.0.000423 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the University College London Infection & Immunity Department for providing the multipoint inoculator that we used for MIC testing. We would also to thank Archibald Coombs for assisting in the MIC testing process.

Funding

The genomic analysis was part funded by the Centre for Antimicrobial Resistance, LSHTM.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VM designed the study, recruited participants, performed laboratory work, and wrote the manuscript. WB recruited participants and performed laboratory work. IS and MH performed MIC testing. SG assisted with MALDI-ToF identification. RS performed WGS, genomic analyses and prepared Figs. 3 and 4. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the LSHTM Research Ethics Committee. Approval was granted on 14/06/2019 (Ref − 17126).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miari, V.F., Bonnin, W., Smith, I.K.G. et al. Carriage and antimicrobial susceptibility of commensal Neisseria species from the human oropharynx. Sci Rep 14, 25017 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75130-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75130-9