Abstract

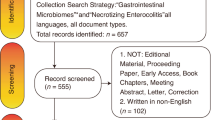

Several perinatal factors influence the intestinal microbiome of newborns during the first days of life, whether during delivery or even in utero. These factors may increase the risk of developing necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) by causing dysbiosis linked to a NEC-associated microbiota, which may also be associated with other gastrointestinal problems. The objective of our study was to evaluate the potential risks associated with microbial shifts in newborns with gastrointestinal symptoms and identify the intestinal microbiota of neonates at risk for NEC.During the study period, 310 preterm and term newborns’ first passed meconium occurring within 72 h of birth were collected, and the microbiome was analyzed. We identified the risk factors in the NEC/FI group. Regarding microbiota, we compared the bacterial abundance between the NEC/FI group at the phylum and genus levels and explored the differences in the microbial composition of the 1st stool samples. A total of 14.8% (n = 46) of the infants were diagnosed with NEC or FI. In univariate analysis, the mean gestational age and birth weight were significantly lower in the NEC/FI group (p < 0.001). Prolonged rupture of membranes (PROM) > 18 h, chorioamnionitis, and histology were significantly higher in the NEC/FI group (p < 0.001). Multivariate analysis showed that gestational age (GA), prolonged membrane rupture (> 18 h), and early onset sepsis were consistently associated with an increased risk of NEC/FI. Infants diagnosed with NEC/FI exhibited a significantly lower abundance of Actinobacteria at the phylum level than the control group (p < 0.001). At the genus level, a significantly lower abundance of Streptococcus and Bifidobacterium which belong to the Actinobacteria phylum, was observed in the NEC/FI group (p < 0.001). Furthermore, the NEC/FI had significantly lower alpha diversities (Shannon Index,3.39 vs. 3.12; P = 0.044, respectively). Our study revealed that newborns with lower diversity and dysbiosis in their initial gut microbiota had an increased risk of developing NEC, with microbiota differences appearing to be associated with NEC/FI. Dysbiosis could potentially serve as a predictive marker for NEC- or GI-related symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Several perinatal and postnatal factors influence the intestinal microbiome of newborns. Microorganisms found in the meconium are the initial colonizers of the newborn gut and originate from the mother’s skin, vagina, and gut1. The gut microbiota inhabits intestinal mucosal surfaces and plays a crucial role in epithelial homeostasis and immune development2. In particular, preterm infants are at increased risk of developing severe bowel disorders characterized by inflammation and infection. Kindinger et al. reported a significant correlation between maternal vaginal microbiota and the risk of preterm or full-term birth3. Similarly, certain neonatal and maternal risk factors contribute to sepsis development in newborns. Factors such as low birth weight, chorioamnionitis, premature birth, and premature rupture of membranes may disrupt the balance of gut microbiota, increasing susceptibility to necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) and infections4. The intestinal microbiota plays a crucial role in immune system maturation, immune response regulation, protection against opportunistic pathogen invasion, and hormonal regulation5. As maternal microbiota is the primary source for the initial colonization of newborn infants, dysbiosis of the neonatal microbiota in the first stool may be closely associated with the prediction of neonatal diseases such as NEC, feeding intolerance (FI), and sepsis during hospitalization. The potential risks associated with microbial shifts in neonates may predict the risk of disease development. A wide variety of reports have demonstrated that the microbiota in the meconium can be affected by factors at the time of delivery. Accordingly, the bacterial diversity observed in NEC patients appears distinct from that of controls, characterized by a lower presence of beneficial microorganisms even before the onset of NEC6. Low diversity of intestinal microbial flora was found without any differences between NEC patients and controls7. As a result, the intestinal microbiome may play an important role in the pathogenesis of NEC which can lead to death, serious infection, and long-term disability and developmental problems6,7. The objective of our study is to investigate whether dysbiosis in the initial gut microbiota increases the risk of developing NEC, with microbiota differences appearing to be associated with NEC/FI in newborns admitted to NICU. Further, significant clinical risk factors associated with NEC or FI that may contribute to dysbiosis were investigated. Additionally, we assessed the diversity of microbiota to identify potential dysbiosis that may predict NEC/FI.

Materials and methods

Population under study and data collection

This was a prospective study carried out at a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) of level IV referral university hospital located in Seoul, Korea. Preterm and term infants admitted to the NICU between May 2021 and September 2023 were included as study participants upon the collection of their first meconium stool sample within 72 h of birth, regardless of whether NEC-related symptoms or signs appeared. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the first meconium stool sample obtained within 72 h of birth during the study period, (2) admission to the NICU regardless of gestational age at birth, (3) immediate NICU admission after birth for any symptoms requiring intensive care, and (4) informed consent obtained from the legal guardians. The control group consisted of infants who met these criteria but did not develop NEC or FI and were considered healthier. Immediately upon passage, a volume of 1–2 mL (maximum 3 mL) of the infant’s meconium was promptly gathered and preserved at − 20 °C. Within 48 h after collection, the specimens were transferred to a deep freezer set at − 80 ◦C until DNA was extracted for microbiome analyses. We excluded infants who died before NICU discharge. Patients with major congenital abnormalities, syndromes, or metabolic diseases were excluded from the study. The specimens were then subjected to DNA extraction for microbiome analyses.

The clinical course and disease progression of the infants included in the study were surveyed until discharge. In addition to collecting perinatal data, we gathered postnatal and clinical information of infants admitted to our level IV NICU. This encompassed details, such as gestational age, birth weight, birth-related history, and major hospital outcomes. Furthermore, we analyzed the rates of feeding advancement, duration of total parenteral nutrition (TPN), and the choice between formula and breast milk. This study was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) under the auspices of the Korean Ministry of Science (grant number: 2022R1A2C100399611). This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Boards at Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital (KC22TNSI0297), and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The written informed consent was obtained from the parents upon admission.

Fecal microbiome analysis

Our previous pilot study examined the relationship between NEC and gestational age in a smaller group setting. The protocols used are described in detail in the methods section of our previous microbiota study8. DNA was extracted from the meconium samples, and, for the target region (V3–V4), specific amplification PCR was conducted. Subsequently, dual index PCR was performed with an Illumina sequencing platform using the PCRBIO VeriFi Mix (PCR Biosystems®, London, UK) and Nextera ® Index Kit V2 Set A (Illumina®, San Diego, CA, USA). After indexing, the final pooled library concentration and size were checked. DNA was pooled and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq platform, and the sequencing data of bacterial variability sites (V3–V4) were analyzed with a 16 S metagenomics application. Then, the sequencing and data analysis were performed using Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology 2 (QIIME2; version 2020.2 and 2020.6). The detailed sampling, preprocessing, and analysis methods used for the meconium samples have been published elsewhere8.

Definitions

Meconium is often defined as the first stool passed within 48 h from birth, however, VLBWI with immature bowel movement with careful advancement of feeding may lead their first meconium pass within 72 h of life. NEC was defined as stage II or above, according to the modified Bell’s staging classification grade9, which includes one or more of the following clinical signs: bilious, gastric aspirator emesis, abdominal distention, or occult or gross blood in the stool. This classification also includes one or more of the following radiographic findings: pneumatosis intestinalis, hepatobiliary gas, or pneumoperitoneum. Therapeutic decisions were based on clinical staging. FI was defined as persistent gastric aspirates of > 50% of the feed volume more than three times a day, which did not allow the advancement of feeding > 10–20 ml/kg/day with or without increased abdominal girth in the absence of culture-positive sepsis or radiographic evidence of NEC during 48 h10. Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) was diagnosed on the basis of both clinical and radiographic findings. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia was defined as the use of oxygen ≥ 0.21% at corrected 36 weeks. Sepsis was diagnosed in patients with symptoms and/or signs of systemic infection. Blood-proven sepsis was defined as a positive result for one or more bacterial or fungal cultures obtained from the blood of infants with clinical signs of infection, treated with antibiotics for 5 or more days, or treated for a shorter period if the patient died11. Early sepsis was classified as sepsis occurring within a week of life and late-onset sepsis (LOS) as they occurred after 7 days of life. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) was diagnosed if oxygen use exceeding 0.21% was still required at a corrected gestational age of 36 weeks. Full feeding was defined as the attainment of enteral feeding exceeding > 100 ml/kg/day, at which point the peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) could be removed.

Statistical analysis

For descriptive statistics of demographic data and concentration, continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations (SD), while categorical variables were presented as percentages and frequencies. For inferential statistics, continuous variables were compared using the t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test, depending on the normality of the variable being tested. More specifically, we compared the microbiome concentrations in the NEC group versus controls using the student’s t test (or Welch-Satterthwaite t test when the variance in the two groups was unequal). Alpha diversity was calculated using Shannon’s diversity index, and beta diversity was plotted using principal coordinate analysis of Bray-Curti’s dissimilarity. Differences in categorical variables were compared using chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Comparison of the clinical characteristics of the NEC/FI group versus control group

During the study period, 310 preterm and term infants born between gestational ages 22 weeks and 40 weeks at the level IV NICU of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital were included in the study. The patients who did not present with any GI (gastrointestinal) symptoms during the NICU admission period were divided into two groups: the NEC/FI group and the control group. A total of 14.8% (n = 46) of the infants were diagnosed with NEC or FI. Perinatal and postnatal clinical factors associated with an increased risk of NEC/FI were investigated during hospitalization. In univariate analysis, the mean gestational age and birth weight were significantly lower in the NEC/FI group (p < 0.001). Prolonged rupture of membranes (PROM) > 18 h, chorioamnionitis, and histology were significantly higher in the NEC/FI group (p < 0.001). Steroid use, IVF conception, and congenital infections were also significantly higher in the NEC/FI group (p < 0.001), along with a higher incidence of resuscitation requiring intubation, compression, and medication at delivery(p < 0.001). Maternal diabetes mellitus (DM), Maternal antibiotics > 3days, sex, and caesarean section were not significantly different between the two groups (Table 1).

In terms of clinical outcomes, prematurity-related morbidities such as respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), and chronic lung disease (CLD) were significantly more prevalent in the NEC and FI group (p < 0.001). Additionally, the infants in this group required a longer time to reach full feeding and experienced extended periods of total parenteral nutrition and mechanical ventilation(p < 0.001). Furthermore, both early and late sepsis rates were significantly elevated in the NEC and FI groups, which was accompanied by a higher incidence of prematurity-associated morbidities, such as patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), and chronic lung disease (CLD). The infants in this group also required a longer time to reach full feeding and experienced extended periods of total parenteral nutrition. Notably, breastfeeding was more commonly achieved among the infants in the NEC/FI group during their NICU stay (Table 2).

NEC/FI risk factor in a multivariable logistic regression analysis

NEC/FI risk factors were examined using multivariable logistic regression analysis. Given the significance of GA and birth weight as contributing factors to sepsis, we further investigated the impact of potential confounding factors on NEC through significant variables in the univariate analysis. Our analysis included GA, birth weight, PROM > 18 h, chorioamnionitis, histology, steroid use, IVF conception, congenital infection, intubation, resuscitation, RDS, Breast milk (≥ 50%), and early and late sepsis, all of which were identified as significant risk factors for NEC/FI. The analysis results consistently showed that gestational age (GA), prolonged rupture of membranes (> 18 h), and early onset sepsis were associated with an increased risk of NEC/FI (Table 3).

Comparison of significant microbiomes between NEC/FI group versus control group

Compared with the control group, infants who had NEC/FI had a significantly lower abundance of Actinobacteria (p < 0.001) at the phylum level (Fig. 1). In the genus level, there were a wide variety of dominant species which were significantly lower in the NEC/FI group, especially showing a significantly lower abundance of Streptococcus and Bifidobacterium (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). The comparison between the control group and the NEC/FI group in a boxplot displaying 18 categories, where the median value exceeded 0.5%, also showed that the relative abundance and types of bacteria at the genus level in the NEC/FI groups showed a significantly lower abundance of Streptococcus and Bifidobacterium(Table 4).

Comparison of alpha diversity (Shannon Index) and beta diversity (Bray–Curti’s dissimilarity) between the NEC/FI and control groups

Compared with the control group, infants who had NEC/FI had significantly lower alpha diversities (Shannon Index,3.39 vs. 3.12; P = 0.044, respectively). However, the number of species identified was not significantly different between the two groups (Fig. 3).

Discussion

In our study, we observed significantly higher rates of PROM > 18 h, chorioamnionitis, and histologic changes in the NEC/FI group, coupled with notably lower mean gestational age and birth weight compared to the non-NEC/FI group (p < 0.001). Similarly, Cekmez et al. reported that certain neonatal and maternal risk factors such as low birth weight, chorioamnionitis, prematurity, and premature rupture of membranes may disrupt the balance of gut microbiota, increasing the susceptibility to NEC and infections4. The prevalence of preterm infants at risk of inflammatory conditions, such as PROM > 18 h and chorioamnionitis, suggests a pivotal role in either the acquisition or deficiency of beneficial intestinal microbiota before NEC development.

Meconium is not sterile, and the neonatal meconium microbiota often reflects the intrauterine microbial community12. Meconium is often defined as the first stool passed within 48 h of birth; however, VLBWI with immature bowel movements and careful advancement of feeding may lead their first meconium pass within 72 h of life. Neonatal microbiotas start to diversify quickly after birth, and compared to adults or older children, infant microbiota is known to have lower diversity as well as an unstable and highly dynamic microbiota structure13. In healthy full-term neonates, the gut and the immune system regulate the microbial community to ensure proper functioning. However, this balance can be quickly disrupted, especially in situations common in prematurity, such as preterm rupture of membranes and chorioamnionitis14. Generally, maternal pregnancy-related health issues and newborn-related outcomes are associated with altered meconium microbiota and are influenced mainly by delivery15,16. Although the initial microbiota of newborns and their maternal contributions remain unclear, immediate perinatal factors influence the microbial composition of the first-pass meconium more than prenatal factors16. Heida et al. emphasized that a NEC-associated gut microbiota was present within days after birth and affects the formation of a NEC-associated microbiota17. Further, Dobbler et al. similarly manifested that decreased diversity and differential abundance of Enterobacteriaceae, as well as an altered community structure, during the first four days of life, correlated with increased risk for developing NEC18. Our study also revealed that NEC/FI had significantly lower abundance of Actinobacteria (p < 0.001) in the phylum level and significantly lower abundance of Streptococcus and Bifidobacterium in the genus level (p < 0.001). Further, the dysbiosis in the initial microbiota of newborns, characterized by lower alpha diversity, was significantly associated with the NEC/FI group in the later days of life.

With respect to morbidities, we also noted a significantly higher incidence of early and late sepsis in the NEC/FI group, along with a greater prevalence of RDS (p < 0.001), potentially attributable to prematurity-related factors. Since RDS is strongly related to prematurity, infants born before 30 weeks of gestational age (GA) often exhibit lower diversity and dysbiosis in their initial gut microbiota8. However, in our multivariate analysis, gestational age (GA), prolonged rupture of membranes (> 18 h), and early onset sepsis consistently exhibited associations with an increased risk of NEC/FI. Our findings support the notion that the microbiota composition of the initial stool is primarily influenced by the presence of inflammatory conditions at the time of delivery, suggesting an early perturbation of the preterm gut microbiome before bacterial maturation3,4,5. Building upon our previous research, the current study adds valuable insights into the complex interplay between inflammatory factors, microbiota dynamics, and NEC pathogenesis in preterm infants, as the first stool is mainly influenced by the possibility of inflammatory conditions and reflects dysbiosis, which can be a risk factor for early disruption of the gut before achieving bacterial maturation. According to our previous study examining the relationship between NEC and gestational age8, events occurring at or soon after birth were found to be important in the development of NEC. Therefore, changes in the gut microbiome during the immediate perinatal period may be a key driver of NEC or feeding intolerance. Our findings are also consistent with a study that found a clear difference in the meconium microbiota between preterm infants with and without sepsis, noting that chorioamnionitis is one of the major risk factors for sepsis19.

Regarding to microbiota, NEC/FI had significantly lower abundance of Actinobacteria in the phylum level and, in the genus level, there were a wide variety of dominant species which were significantly lower in the NEC/FI group, especially showing a significantly lower abundance of Streptococcus and Bifidobacterium. Our study also showed significantly lower alpha diversity of the meconium microbiota in the NEC/FI group, which is more prone to infection20, suggesting that a lack of diverse colonization and predominance of pathogenic bacteria may increase the risk of infection and bacterial translocation21. Lower diversity of gut microbiota is also known to be a driver of many diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, acute diarrheal disease, C. difficile infection, as well as in cancer patients22,23,24. The genus Bifidobacterium belongs to the Actinobacteria phylum. Bifidobacteria are among the dominant bacterial populations in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and mostly found in breast-fed infants because of the variety of oligosaccharides present in human milk25. Bifidobacterium-mediated health benefits are the result of a complex dynamic interplay established between bifidobacteria, other members of the gut microbiota, and the human host, and further studies are warranted in the future26. Recent studies have shown that the predominant early colonizers of the infant gut are maternal fecal bacteria, mainly Bifidobacterium and Bacteroides, and Clostridium27,28,29. Bifidobacterium has been found more frequently in breast-fed infants, which harbor a more complex and numerous Bifidobacterium microbiota than formula-fed infants26. Bifidobacteria are well known for their ability to utilize human milk oligosaccharides and reduce the overrepresentation of enteropathogenesis, thereby increasing disease risk30,31. Among the proposed benefits of bifidobacteria, inhibition of enteropathogenesis and reduction of rotavirus infection stand out32. Most recently, Koleva et al. reported that the depletion of CD71 + erythroid cells (CECs) results in an inflammatory response to microbial communities in newborn mice. In this study, intestinal CECs are highly abundant in the early stages of life and possess a unique phenotype characterized by elevated expression levels. However, disturbances in mucosal homeostasis can allow unrestrained access of normal gut residents, leading to an inflammatory response. Ultimately, Koleva et al. emphasized that changes in microbial communities are directly linked to the reduction of CECs which can be a contributing factor to NEC33. On the other hand, breast milk, which serves as an exclusive source of nutrition for newborns alongside formula, stimulates beneficial bacteria that directly influence the development of host defenses34. Several studies have suggested that probiotics administered to preterm infants may protect against developing NEC35. Gregory et. reported profound effects of breast milk on the composition and diversity of colonizing intestinal populations. Infants who were fed breast milk had a greater initial bacterial diversity and a more gradual acquisition of diversity than infants who were fed infant formula36. Further randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are warranted to explore the significant association with dysbiosis.

In summary, our primary focus was on investigating the initial composition of the gut microbiota reflecting the perinatal gut microbiome of the infant and its association with NEC/FI. We aimed to identify significant microbial changes during the immediate perinatal period, which could later be a driving factor for NEC or FI. Our study provides valuable insights into the complex interplay between inflammatory factors, microbiota dynamics, and NEC pathogenesis in preterm infants.

Strengths and limitations

This study is unique in its prospective enrollment of all newborns admitted to the level IV NICU and assessment of their first meconium within the first 3 days of admission. However, this study had a few limitations. First, the study lacked a longitudinal analysis of the changes in the gut microbiota of neonates after birth. Second, the sample size is relatively small for making distinctive comparisons between groups. Nevertheless, our study involves the largest prospective cohort of neonates in South Korea to date, ensuring a representative sample across racial demographics.

Conclusion

In summary, this study revealed that newborns with lower diversity and dysbiosis in their initial gut microbiota had an increased risk of developing NEC, and microbiota differences were associated with NEC/FI. Additionally, infants with NEC/FI presented significantly lower alpha diversity. GA, PROM (> 18 hours), and early-onset sepsis were consistently associated with an increased risk of infants with NEC/FI. These findings suggest that the gut microbiome of NEC infants is vulnerable, and that the initiation of NEC-associated microbiota formation may even occur before birth. Further studies are warranted to better understand the role and impact of the microbiota in disease pathogenesis in vulnerable newborns.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the information contained in the data must be protected as confidential and will only become available to those who have obtained permission from the data review board and the IRB of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital. However, the data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ferretti, P. et al. Mother-to-infant microbial transmission from different body sites shapes the developing infant gut microbiome. Cell. Host Microbe. 24 (1), 133–145e135 (2018).

Kolodziejczyk, A. A., Zheng, D. & Elinav, E. Diet-Microbiota interactions and personalized nutrition. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17 (12), 742–753. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-019-0256-8 (2019).

Kindinger, L. M. et al. Relationship between vaginal microbial dysbiosis, inflammation, and pregnancy outcomes in cervical cerclage. Sci. Transl Med. 8, 350ra102 (2016).

Cekmez, Y., Güleço˘glu, M. D., Özcan, C., Karadeniz, L. & Kiran, G. The utility of maternal mean platelet volume levels for early onset neonatal sepsis prediction of term infants. Ginekol. Pol. 88, 312–314 (2017). [CrossRef].

Neu, J. & Walker, W. A. Necrotizing enterocolitis. New. Engl. J. Med. 364, 255–264 (2011). [CrossRef].

Mai, V. et al. Fecal microbiota in premature infants prior to necrotizing enterocolitis. PLoS One. 6, e20647 (2011).

Normann, E., Fahlén, A., Engstrand, L. & Lilja, H. E. Intestinal microbial profiles in extremely preterm infants with and without necrotizing enterocolitis. Acta Paediatr. 101 (11), 1121–1127 (2012).

Kang, H. M. & Kim, S. Seok Hwang-Bo, In Hyuk Yoo, Yu-Mi Seo, Moon Yeon Oh, Soo-Ah Im and Young-Ah Youn. Pathogens. ;12(1):55. (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12010055

Bell, M. J. et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging. Ann. Surg. 187, 1–7 (1978).

Carlos, M. A., Babyn, P. S., Marcon, M. A. & Moore, A. M. Changes in gastric emptying in early postnatal life. J. Pediatr. 130, 931–937 (1997).

Hansen, N. et al. Late-onset sepsis in very low birth weight neonates: the experience of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics. 110 (2), 285–291 (2002).

Ardissone, A. N. et al. Meconium microbiome analysis identifies bacteria correlated with premature birth. PLoS One. 9 (3), e90784 (2014).

Hodzic, Z., Bolock, A. M. & Good, M. The role of mucosal immunity in the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis. Front. Pediatr. 5, 40 (2017). [CrossRef].

Wardwell, L. H., Huttenhower, C. & Garrett, W. S. Current concepts of the intestinal microbiota and the pathogenesis of infection. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 13 (1), 28–34 (2011).

Jenni Turunen, M. V. et al. Investigating prenatal and perinatal factors on meconium microbiota: a systematic review and cohort study. Pediatr. Res. 95 (1), 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-023-02783-z (2024). Epub 2023 Aug 17.

Turunen, J., Tejesvi, M. V. & Paalanne, N. Investigating prenatal and perinatal factors on meconium microbiota: a systematic review and cohort study. Pediatr. Res. 95 (1), 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-023-02783-z (2024).

Heida, F. H. et al. A necrotizing enterocolitis-Associated Gut Microbiota is Present in the meconium: results of a prospective study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 62 (7), 863–870. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw016 (2016). Epub 2016 Jan 19. PMID: 26787171.

Dobbler, P. T. et al. Low microbial diversity and abnormal Microbial succession is Associated with Necrotizing enterocolitis in Preterm infants. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2243. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02243 (2017).

Belkaid, Y. & Hand, T. W. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell. 157, 121–141 (2014).

Madan, J. C. et al. Gut microbial colonisation in premature neonates predicts neonatal sepsis. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 97 (6), F456–F462 (2012).

Stewart, C. J. et al. Longitudinal development of the gut microbiome and metabolome in preterm neonates with late onset sepsis and healthy controls. Microbiome. 5 (1), 75 (2017).

Samuels, N., van de Graaf, R. A., de Jonge, R. C. J., Reiss, I. K. M. & Vermeulen, M. J. Risk factors for necrotizing enterocolitis in neonates: a systematic review of prognostic studies. BMC Pediatr. 17, 105 (2017). [CrossRef].

Bäckhed, F. et al. Dynamics and stabilization of the human gut microbiome during the First Year of Life. Cell. Host Microbe. 17, 690–703 (2015).

Neish, A. S. Microbes in gastrointestinal health and disease. Gastroenterology. 136, 65–80 (2009).

Dornellesa, L., Procianoya, R. S., Roeschb, L. F., Corsoa, A. L. & Dobblerb, Volker Silveira, M. R. Meconium microbiota predicts clinical early-onset neonatal sepsis in preterm neonates. J. Mater. Fetal Nenon. Med.. (35), 10 1935–1943 https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2020.1774870 (2022).

Hidalgo Cantabrana, C., Delgado, S., Ruiz, L. & Ruas-Madiedo Patricia Sánchez Borja, Margolles A. Bifidobacteria and their health-promoting effects. Clin. Microbiol. 2017 (5):3 https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.bad-0010-2016

Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852–857 (2019). [CrossRef] [PubMed].

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods. 13, 581–583 (2016). [CrossRef].

Davis, N. M., Proctor, D. M., Holmes, S. P., Relman, D. A. & Callahan, B. J. Simple statistical identification and removal of contaminant sequences in marker-gene and metagenomics data. Microbiome. 6, 226 (2018). [CrossRef].

Mariat, D. et al. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio of the human microbiota changes with age. BMC Microbiol. 9, 123. (2009).

Roger, L. C., Costabile, A., Holland, D. T., Hoyles, L. & McCartney, A. L. Examination of faecal Bifidobacterium populations in breast- and formula-fed infants during the first 18 months of life. Microbiology. 156, 3329–3341. https://doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.043224-0 (2010).

Muñoz, J. A. et al. Novel probiotic Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis CECT 7210 strain active against rotavirus infections. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 8775–8783 (2011).

Koleva, P. et al. CD71 + erythroid cells promote intestinal symbiotic microbial communities in pregnancy and neonatal period. Microbiome. 12 (1), 142. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-024-01859-0 (2024). PMID: 39080725; PMCID: PMC11290123.

Groer, M. W., Gregory, K. E., Louis-Jacques, A., Thibeau, S. & Walker, W. A. The very low birth weight infant microbiome and childhood health. Birth Defects Res. C Embryo Today. 105 (4), 252–264 (2015).

Repa, A. et al. Probiotics (Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium bifidum) prevent NEC in VLBW infants fed breast milk but not formula. Pediatr. Res. 77 (2), 381–388 (2015).

Gregory, K. E. et al. Influence of maternal breast milk ingestion on acquisition of the intestinal microbiome in preterm infants. Microbiome. 4 (1), 68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-016-0214-x (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank AIBIOTICS Co., Ltd., for their technical and statistical assistance and our NICU team at Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) under the auspices of the Korean Ministry of Science (grant number 2022R1A2C100399611).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions: Y.Y.A., K.S.Y. and K.H.M designed the patient study; Y.Y.A., C.H.J, K.S.Y, I.S.A and K.H.M conducted the research. Y.Y.A. wrote the paper and had the primary responsibility.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

We, the authors, provided consent for publication. Medical records are available in the Archive of the Department of Pediatrics of the Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital (KC22TNSI0297).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chae, H., Kim, S.Y., Kang, H.M. et al. Dysbiosis of the initial stool microbiota increases the risk of developing necrotizing enterocolitis or feeding intolerance in newborns. Sci Rep 14, 24416 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75157-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75157-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Transcriptional stratification of necrotizing enterocolitis identifies distinct disease subtypes

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

The microbiome’s hidden influence: preclinical insights into inflammatory responses in necrotizing enterocolitis

Seminars in Immunopathology (2025)