Abstract

Nanostructures are tiny objects at the molecular and microscopic scale, with carbon nanotubes being the most notable among them. The elements possess exceptional microelectronic properties and other unique characteristics. Researchers have recently focused on the mathematical features of these materials. Molecular descriptors are crucial in mathematical chemistry, particularly in QSAR and QSPR modeling. Topological indices hold a significant position among them. This study presents the precise formulation of the ten most crucial topological indices for a benzene ring positioned on a P-type surface within the highly symmetric 2D lattice \(\hbox {BCZ}_{48}\). We have incorporated the computed indices to develop a predictive model for the graph energy of the 2D lattice and, in addition, provided the NMR patterns and the HOMO-LUMO gap.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A mathematical model is an explanation of a structure, exhausting mathematical and linguistic ideas. The process of mounting a mathematical model is called mathematical modeling. These models are used in the sciences of nature, the various disciplines of engineering, and social sciences. One such example is the graph-theoretic model. A study of the graph is an essential branch of discrete mathematics. It is a mathematical structure used to model pairwise relationships among entities. The entities could be anything; in particular, we take the entities as atoms of the molecule, and pairwise relationships among entities are called bonds. Graph-theoretically, vertices are mapped as atoms, and edges are mapped to bonds. This leads to another new subfield of mathematical chemistry, which is called chemical graph theory. Molecular descriptors are crucial in mathematical chemistry, particularly in QSPR and QSAR modelling1,2. Topological indices hold a significant position among them. Currently, there are numerous topological indices with applications across different branches of chemistry. A topological index (TI) is a numerical value calculated from the chemical structure using mathematical methods3,4,5,6,7,8,9.

In 1947, Wiener first proposed the concept of the topological index while conducting an experiment on the boiling point of paraffin10. This index was based on the sum of the shortest distances between every pair of vertices. The shortest distance is the length of a shortest path. The shortest path problem in network science has many applications in engineering, science and technology. For example, shortest path in LEO satellite constellation networks11. The real-life application on network science can be found in12,13,14,15. Topological indices are associated with physicochemical properties such as stability, strain energy, boiling point, ESR spectroscopy, and NMR spectroscopy. For recent work on this topic, see17,18,19,20,21,22.

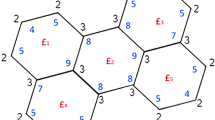

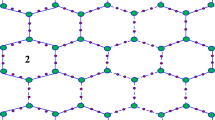

Carbon materials can be categorized based on their dimensions, electronic band structures, and hybridized states. The \(\hbox {sp}^2\)-hybridized carbon allotropes are further subdivided into three categories according to surface curvature. Fullerenes exhibit spherical shapes with positive Gaussian curvature, while carbon nanotubes (CNTs) have cylindrical structures with zero Gaussian curvature. Conversely, schwarzites are characterized as carbon allotropes with typical negative curvature23,24,25,26. C-schwarzites are graphite-like networks characterized by negative Gaussian curvature, typically referred to as P and D surfaces. In contrast to the positive curvature in fullerenes, which is caused by 5-membered rings, the negative curvature in schwarzites arises from the presence of 7- or 8-membered rings. BN-schwarzites, as binary compounds, are hypothesized to feature architectures composed solely of 6- and 8-membered rings, as shown in Figure 1.

In the study conducted in27, polybenzene was characterized as a \(6\cdot 8^2\) net embedded in the infinite periodic minimal D-surface. It consisted of a single type of carbon atom and was anticipated to possess significantly lower energy per atom compared to the reference structure \(\hbox {C}_{60}\) in the field of nanoscience. It is alternatively referred to as a \(6\cdot 8^2\) framework integrated within the periodic minimal P-surface. The development of a rational structure for three benzene-based units is examined in the study conducted by28. The benzene ring is embedded in the D-surface with a value of \(\hbox {BTA}_{48}\), in the P-type-surface with a value of \(\hbox {BCZ}_{48}\), and in the P-type-surface with a value of \(\hbox {BCA}_{96}\).

The construction of these structures was made with the help of some experiments on maps29,30,31, applied on Platonic solids: the sequence of polygon-4 and leapfrog operations, \(Le(P_4(M))\), the tetrahedron (T), cube (C) was used to construct the molecular structures \(\textrm{BCA}_{96}\) and \(\textrm{BTA}_{48}\). By extending the cage produced by the octahedron, the molecular structure of \(\textrm{BCZ}_{48}\) is defined. In all these structures, B connotes the benzene path of tessellation. C or T denotes the Platonic on which the map operations acted, A stands for armchair, and Z comes from the zig-zag ending of a nanotube. The last number in the notation denotes the cardinality of carbon atoms in the structures. We denote the molecular graph of \(\textrm{BCZ}_{48}\) as BCZ(m, n). Similarly, the molecular graphs of \(\textrm{BTA}_{48}\) and \(\textrm{BCA}_{96}\) are denoted as BTA(m, n) and BCA(m, n), respectively. In this study, we focus on the molecular graph BCZ(m, n), which contains 24mn vertices and \(32mn-2m-2n\) edges. Furthermore, the graph is bipartite, as evident from the unit cell of \(\textrm{BCZ}_{48}\) and its construction shown in Figure 1.

The M-polynomial of BCZ(m, n) was obtained in32, and thereby the authors found few degree-based topological indices. Zagreb polynomials and a few more TIs were discussed in33. The degree-based TIs of line graphs of BCZ(m, n) were dealt with in34. A theoretical investigation of \(\textrm{BTA}_{48}\) based on density functional theory was done in35. With this motivation, we compute the ten most important distance based topological indices, develop a predictive model for graph energy, and provide NMR patterns for BCZ(m, n).

Graph-theoretical concepts

Let G be a graph with vertex set V(G) and edge set E(G). For \(e_1= u_1u_2 \in E(G)\), we define

Their cardinalities, \(|N_{u_1}(e_1|G)|=n_{u_1}(e_1|G)\) and \(|M_{u_1}(e_1|G)|=m_{u_1}(e_1|G)\). The terms \(n_{u_2}(e_1|G)\) and \(m_{u_2}(e_1|G)\) are similar. The strength-weighted concept was initiated in36 and later used in37,38,39,40,41,42 as \(G^* = (G, (v_{w}, v_s), e_s)\) where \(v_w\) is vertex weight, \(v_s\) is the vertex strength and \(e_s\) is the edge strength. Table 1 summaries the TIs with strength-weighted parameters, while for simple graphs, refer to43,44. It should be noted that \(d_{G^*}(u_1, u_2)= d_G(u_1, u_2)\) for any \(u_1,u_2 \in V(G^*)\) and \(D_{G^*}(e_1, e_2)= D_G(e_1, e_2)\) for any \(e_1,e_2 \in E(G^*)\). Similarly, the sets \(N_{u_1}(e_1|{G^*})= N_{u_1}(e_1|G)\) and \(M_{u_1}(e_1|{G^*})= M_{u_1}(e_1 |G)\) are defined with cardinality

The values of \(n_{u_2}(e_1|G^*)\) and \(m_{u_2}(e_1|G^*)\) are analogous. The degree of the vertex \(u_1\) in \(G^*\) is defined as \(d_{G^*}(u_1) = \sum \limits _{v \in N_{G^*}(u_1)}e_s(u_1v)\). Denote \(\{1,2,3,\ldots , n\}\) as \(\mathbb {N}_n\), and therefore \(1\le i \le n\) as \(i\in \mathbb {N}_n\).

The cut approach proved to be very useful for handling distance-based graph invariants, which are fundamental ideas in chemical graph theory. There are other methods to find the distance-based invariants, but they do not serve the purpose of finding all indices. Those techniques explained in45,46 are restricted to serving a few. For a comprehensive understanding of the cut process, please consult the latest survey by43. Partial cubes, isometric subgraph, Djoković-Winkler \(\varTheta\) condition, and convex subgraph are important components of the cut method. The well-defined collection of hypercubes’ subgraphs is termed a partial cube47. The canonical metric representation was discussed in48 to prove all benzenoid systems are partial cubes. The condition, \(d_G(s_1,s_2)+d_G(t_1,t_2)\ne d_G(s_1,t_2)+d_G(t_1,s_2)\) for two edges \(e_1=s_1t_1\) and \(e_2=s_2t_2\) is called Djoković-Winkler (\(\varTheta\)) relation. Recently, Prabhu et al. proved that the anti-kekulene system also falls under partial cubes20. It satisfies the first two conditions of the equivalence relation and fails to follow the third in general. Hence, the \(\varTheta\) partitions of the edge set of a partial cube G into classes \(F_1, F_2,\ldots F_r\), called \(\varTheta\)-classes or convex cuts. However, its transitive closure \(\varTheta ^{*}\) forms an equivalence relation and partitions the edge set into many convex components. A partition \(\mathscr {E} = \{E_{1},E_{2}, \ldots E_{k}\}\) of E(G) is considered coarser than partition \(\mathscr {F}\) if every set \(E_{i}\) is composed of one or more \(\varTheta ^{*}\)-classes of G. The quotient graph \(G/E_i\) is created from the disconnected graph \(G-E_i\) by treating the connected components as vertices. Two components \(C_j^i\) and \(C_k^i\) are connected in \(G/E_i\) if there exists an edge \(xy\in E_i\) where x is in \(C_j^i\) and y is in \(C_k^i\).

Mathematical results

Theorem 1

Let G be a BCZ(m, n) lattice structure, where \(m,n\ge 1\). Then,

-

(i)

\(W(G)= -(4m(216m^4 - 1080m^3n - 720m^2n^2 + 20m^2 - 2880mn^3 + 120mn + 180n^2 + 30n - 101))/15\).

-

(ii)

\(W_e(G)= (- 1536m^5 + 7680m^4n + 5120m^3n^2 - 2560m^3n - 120m^3 + 20480m^2n^3 - 12480m^2n^2\)\(+ 1060m^2n - 60m^2 - 2560mn^3 + 460mn^2 + 560mn + 681m + 80n^3 - 60n^2 - 35n)/15\).

-

(iii)

\(W_{ve}(G)= -(4m(288m^4 - 1440m^3n - 960m^2n^2 + 240m^2n + 20m^2 - 3840mn^3 + 1170mn^2\)\(+ 90mn + 240n^3 + 150n^2 - 45n - 128))/15\).

-

(iv)

\(Sz_v(G)= (8m(- 96m^3 + 1152m^2n^3 + 156m^2n - 8m^2 + 24mn + 69m - 36n^3 - 6n + 8))/3\).

-

(v)

\(Sz_e(G)= (- 384m^5 + 9600m^4n - 8400m^4 + 81920m^3n^3 - 39680m^3n^2 + 16680m^3n + 520m^3\)\(- 12800m^2n^3 + 2640m^2n^2 - 5560m^2n + 5880m^2 - 120mn^3 + 200mn^2 + 100mn - 256m - 120n^3)/15\).

-

(vi)

\(Sz_{ev}(G)= (8m(- 18m^4 + 450m^3n - 660m^3 + 7680m^2n^3 - 1860m^2n^2 + 1170m^2n + 5m^2 - 600mn^3\)\(- 180mn + 480m - 150n^3 + 15n^2 - 30n + 13))/15\).

-

(vii)

\(Sz_t(G)= (- 672m^5 + 16800m^4n - 22800m^4 + 250880m^3n^3 - 69440m^3n^2 + 41640m^3n + 280m^3\)\(- 22400m^2n^3 + 2640m^2n^2 - 7480m^2n + 16320m^2 - 3960mn^3 + 440mn^2 - 620mn + 272m - 120n^3)/15\).

-

(viii)

\(PI(G)= 32m^3 + 1024m^2n^2 - 232m^2n + 8m^2 - 136mn^2 + 8mn - 16m + 8n^2\).

-

(ix)

\(S(G)= -(16m(288m^4 - 1440m^3n - 960m^2n^2 + 240m^2n + 20m^2 - 3840mn^3 + 450mn^2\)\(+ 135mn + 240n^3 + 195n^2 - 45n - 128))/15\).

-

(x)

\(Gut(G)= (- 6144m^5 + 30720m^4n + 20480m^3n^2 - 10240m^3n + 81920m^2n^3 - 19200m^2n^2 - 1160m^2n\)\(- 60m^2 - 10240mn^3 - 2120mn^2 + 2480mn + 2484m + 320n^3 - 60n^2 - 140n)/15\).

Proof

Let \(\{Z_{1i} : i \in \mathbb {N}_{m-1}\}\), \(\{Z_{2i} : i \in \mathbb {N}_{n-m+1}\}\), \(\{O_{1i} : i \in \mathbb {N}_m\}\), \(\{O_{2i} : i \in \mathbb {N}_{n-m}\}\), \(\{V_i : i\in \mathbb {N}_{2n-1}\}\) and \(\{H_i : i \in \mathbb {N}_{2m-1}\}\) be the different cuts of BCZ(m, n). For reference, cuts of BCZ(4, 6) are depicted in Figures 2, 3, and 4. The quotient graphs \(G/ Z_{1i}\), \(G/ Z_{2i}\) are isomorphic to \(K_{2,4i}\) and \(K_{2,4m}\), depicted in Figures 5(a) and (b). The quotient graphs corresponding to obtuse, vertical and horizontal cuts \(G/O_{1i}\), \(G/O_{2i}\), \(G/ V_{i}\) and \(G/ H_{i}\) are path on two vertices and respectively depicted in Figures 6(a), (b), (c) and (d) along with their edge strengths. The vertex strength-weighted values of all these quotient graphs are given in Table 2.

The above expressions are simplified using Table 2 to derive the mathematical results. \(\square\)

The degree-based indices of BCZ(m, n) were discussed in32,33 and are stated below. The numerical values of the distance based indices discussed in this paper are given in Table 3, while the degree based indices are provided in Table 4. Figures 7(a) and (b) depict the graphical representation of Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Theorem 2

32,33 Let G be a BCZ(m, n), \(m,n\ge 1\). Then,

-

(i)

\(M_{1}(G) = 176mn-20m-20n.\)

-

(ii)

\(M_{2}(G) = 240mn-38m-38n.\)

-

(iii)

\(HM(G) = 196mn-152m-152n.\)

-

(iv)

\(H(G) =\frac{1}{15}\left[ 176mn\right] .\)

-

(v)

\(GA(G)= \frac{1}{5}\left[ \left( 32\sqrt{6}+80\right) mn-10m-10n\right] .\)

-

(vi)

\(AZ(G) =\frac{1}{32} \left[ 9928mn-1163m-1163n\right] .\)

-

(vii)

\(ABC(G)=\frac{1}{3}\left[ (24\sqrt{2}+32)mn+\left( 6\sqrt{2}-12\right) m+\left( 6\sqrt{2}-12\right) n\right] .\)

-

(viii)

\(R(G)=\frac{1}{3}\left[ 8\sqrt{6}+16\right] mn.\)

-

(ix)

\(SDD(G) =\frac{1}{3}\left[ 200mn-12m-12n\right] .\)

-

(x)

\(ISI(G)=\frac{1}{5}\left[ 216mn-25m-25n\right] .\)

Applications to graph energy and \(^{13}\)C NMR signals

Graph energy was introduced as a mathematical abstraction of \(\pi\)-electron energy, based on the idea that the two are approximately proportional. This connection emerged from the study of molecular orbital theory in conjugated hydrocarbons, such as benzene49,50. As a result, graph energy has become a useful tool for developing mathematical models51 to analyze molecular stability and reactivity.

The graph energy of a molecular graph G is mathematically defined as the sum of the absolute values of the eigenvalues of the adjacency matrix of G. Suppose \(\lambda _1, \lambda _2, \dots , \lambda _p\) are the eigenvalues of G with order p. Then, the graph energy \(E_\pi\) of G is defined as

The computational difficulties of calculating graph energy arise primarily from determining the eigenvalues from the characteristic polynomial, which becomes increasingly challenging for large and complex graphs. This challenge has spurred the development of algorithms and mathematical models. In this study, we formulate a mathematical model for predicting graph energy using distance-based topological indices, as discussed in the earlier section. We use the newGRAPH package52 to compute the graph energy for specific dimensions, as presented in Table 5. As we see from Table 3, the distance-based indices increase rapidly with the structure’s dimension. Therefore, we scale the indices based on their vertex and edge contributions during computation. Vertex-contributed indices, such as W, \(W_{e}\), \(W_{ve}\), S, and Gut, are divided by the number of vertices, while indices such as \(Sz_{v}\), \(Sz_{e}\), \(Sz_{ev}\), \(Sz_{t}\), and PI are divided by the number of edges. These scaled indices are then correlated with the graph energy values, revealing that PI has the highest correlation, as shown in Table 5, where \(PI^* = PI/|E|\). The resulting equation is given below.

where correlation coefficient \(r=0.999993384\), F-value \(F=453447.0452\), and standard error \(SE=3.102795978.\)

Applications of machine learning related to spectroscopy and BCZ stability can make use of the topological information stored in the adjacency and distance matrices of these structures. It is feasible that we will be able to design a strategy for the vertex partitioning of BCZ if we take the distance matrices of these structures and use them to create the distance degree sequence vectors (DDSV) for each vertex of BCZ. Such a strategy would allow us to partition the vertex connections of these structures. For the purpose of generating the vertex divisions, graph theory is the only instrument that is employed within the context of this approach; experimental reference values are not utilized in any way. In spite of the fact that the DDSV equivalence does not always exhibit isomorphism with the automorphic equivalence of vertices, Quintas and colleagues53 demonstrated that DDSVs can be employed to study network vertices. The number of vertices in BCZ that are at distance j from any vertex \(v_i\) is represented as \(D_{ij}\). The set \(\{D_{i0}, D_{i1}, D_{i2},... D_{ij},...\}\) represents the DDSV of every vertex in BCZ.

It is possible to produce the DDSV of each vertex in any dimension of BCZ, as described in the sources given in52. This can be accomplished by utilising the newGRAPH interface. Following that, Python code is utilized in order to study the DDSVs that have been assigned to each vertex. When a significant number of DDSVs are exchanged, sets of vertices will begin to converge. Constructing nuclear divisions is challenging due to the presence of multiple nuclei associated with vectors of varying DDSV lengths, which complicates the process. However, with the assistance of MATLAB code developed using analytical equations, the numerical findings for the topological descriptors of BCZ were successfully verified.

According to the data presented in Table 6, the four distinct dimensions each exhibit their own unique nuclear equivalence classes. All of their atomic identities, connectivities, and automorphic symmetries are highly distinct from one another. Given the considerable number of different carbon nuclear equivalence classes, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy of carbon-13 (C-13) should be an effective tool for comparing the various dimensions. For the purpose of forecasting the quantity of \(^{13}\)C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) signals, as well as the patterns of their intensity, the nuclear equivalence class structures, which are displayed in Table 6, can be utilized. Consequently, \(^{13}\)C NMR spectroscopy is an effective tool for investigating the structures of specific assemblies.

The HOMO-LUMO gaps, which are indicative of kinetic stability, tend to decrease in the BCZ as the values of m and n increase, as can be seen by examining Table 7. With each increase in m and n, the gap gets closer and closer to being equal to zero. In light of the fact that this is the situation, the vast majority of chains exhibit HOMO-LUMO gaps of BCZ that are almost small. Because this shows that they have triplet spin ground states, it is feasible that BCZ could be advantageous to topological spintronics. This is because of the fact that they have triplet spin ground states. Table 7 contains the energy measurements, which take into consideration the total energy of the \(\pi\)-electron as well as the delocalisation energies for each bond. On the basis of the theoretical estimation of the potential energy, these observations have been accomplished.

Let p be the number of vertices in BCZ. The energy of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) is \(\hbox {E}_{HOMO}\)=\(\lambda _{p/2}\) and the energy of the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) is \(\hbox {E}_{LUMO}\)=\(\lambda _{p/2+1}\). Therefore, HOMO-LUMO gap is \(\delta _{HL}= \lambda _{p/2}-\lambda _{p/2+1}\). The total \(\pi\)-electron energy is \(E_{\pi }=2\sum _{i=1}^{p/2}\lambda _i\) and the delocalization energy is \(E_{Deloc}= E_{\pi }-p\)54. In the above formulas, the energies are stated in conventional \(\beta\)-units in Table 7.

To develop hybrid quantum chemistry techniques better suited for handling large systems, quantum chemical parameterizations can leverage the topological characteristics and matrices that have been computed. For instance, graph theory, in conjunction with Pariser-Parr-Pople processes, effectively manages \(\pi\)-electrons. By applying the CASSCF/CI methods55 to a collection of smaller molecular building blocks, it is possible to determine parameters related to hybrid techniques. Consequently, topological indices that account for distance, such as those using resistance as an indicator, can provide significant advantages and insights into deriving more precise parameters from quantum chemical approaches.

Conclusion

In recent years, molecular topology has emerged as an effective method for drug design and discovery. It involves identifying molecules with similar structural characteristics that exhibit comparable pharmacological activities. In this study, we employed the strength-weighted graph approach to derive distance based topological indices for the 2D lattice of BCZ benzene structures. We developed a linear regression model to predict the graph energy of these structures based on the computed topological indices, achieving high correlation. Additionally, we provided \(^{13}\)C NMR signals and intensity patterns by incorporating distance matrices and presented the HOMO-LUMO gaps for these structures.

Data availibility

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Dearden, J.C. The Use of Topological Indices in QSAR and QSPR Modeling. In: Roy, K. (eds) Advances in QSAR Modeling. Challenges and Advances in Computational Chemistry and Physics, vol 24. Springer, Cham. (2017)

Arockiaraj, M. et al. Novel molecular hybrid geometric-harmonic-Zagreb degree based descriptors and their efficacy in QSPR studies of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. SAR and QSAR in Environmental Research 34, 569–589 (2023).

Hakeem, A., Ullah, A. & Zaman, S. Computation of some important degree-based topological indices for \(\gamma\)-graphyne and zigzag graphyne nanoribbon. Molecular Physics 121(14), e2211403 (2023).

Meharban, S., Ullah, A., Zaman, S., Hamraz, A. & Razaq, A. Molecular structural modeling and physical characteristics of anti-breast cancer drugs via some novel topological descriptors and regression models. Current Research in Structural Biology 7, 100134 (2024).

Arockiaraj, M., Jency, J., Mushtaq, S., Shalini, A. J. & Balasubramanian, K. Covalent organic frameworks: topological characterizations, spectral patterns and graph entropies. Journal of Mathematical Chemistry 61, 1633–1664 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. QSPR analysis of drugs for treatment of schizophrenia using topological indices. ACS Omega 8(44), 41417–41426 (2023).

Shanmukha, M. C. et al. Chemical applicability and computation of K-Banhatti indices for benzenoid hydrocarbons and triazine-based covalent organic frameworks. Scientific Reports 13, 17743 (2023).

Shanmukha, M. C., Usha, A., Basavarajappa, N. S. & Shilpa, K. C. Comparative study of multilayered graphene using numerical descriptors through M-polynomial. Physica Scripta 98(7), 075205 (2023).

Arockiaraj, M. et al. Relativistic distance based and bond additive topological descriptors of zeolite RHO materials. Journal of Molecular Structure 1250, 131798 (2022).

Wiener, H. Structural determination of paraffin boiling points. Journal of the American Chemical Society 69(1), 17–20 (1947).

Chen, Q. et al. Shortest path in LEO satellite constellation networks: An explicit analytic approach. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications 42(5), 1175–1187 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. A differential game approach for real-time security defense decision in scale-free networks. Computer Networks 224, 109635 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. A resource-based dynamic pricing and forced forwarding incentive algorithm in socially aware networking. Electronics 13(15), 3044 (2024).

Xuemin, Z. et al. Self-organizing key security management algorithm in socially aware networking. Journal of Signal Processing Systems 96, 369–383 (2024).

Wang, Q., Hu, J., Wu, Y. & Zhao, Y. Output synchronization of wide-area heterogeneous multi-agent systems over intermittent clustered networks. Information Sciences 619, 263–275 (2023).

Gutman, I., & Trinajstić, N. Graph theory and molecular orbitals. Total \(\pi\)-electron energy of alternant hydrocarbons. Chemical Physics Letters 17(4), 535–538 (1972).

Govardhan, S., Roy, S., Balasubramanian, K. & Prabhu, S. Topological indices and entropies of triangular and rhomboidal tessellations of kekulenes with applications to NMR and ESR spectroscopies. Journal of Mathematical Chemistry 61(7), 1477–1490 (2023).

Govardhan, S., Roy, S., Prabhu, S. & Arulperumjothi, M. Topological characterization of cove-edged graphene nanoribbons with applications to NMR spectroscopies. Journal of Molecular Structure 1303, 137492 (2024).

Arockiaraj, M., Prabhu, S., Arulperumjothi, M., Kavitha, S. R. J. & Balasubramanian, K. Topological characterization of hexagonal and rectangular tessellations of kekulenes as traps for toxic heavy metal ions. Theoretical Chemistry Accounts 140, 43 (2021).

Prabhu, S., Arulperumjothi, M., Manimozhi, V. & Balasubramanian, K. Topological characterizations on hexagonal and rectangular tessellations of antikekulenes and its computed spectral, nuclear magnetic resonance and electron spin resonance characterizations. International Journal of Quantum Chemistry 124(7), e27365 (2024).

Ullah, A., Jama, M. & Zaman, S. Shamsudin, Connection based novel AL topological descriptors and structural property of the zinc oxide metal organic frameworks. Physica Scripta 99(5), 055202 (2024).

Hayat, S., Suhaili, N. & Jamil, H. Statistical significance of valency-based topological descriptors for correlating thermodynamic properties of benzenoid hydrocarbons with applications. Computational Theoretical Chemistry 1227, 114259 (2023).

Lherbier, A., Terrones, H. & Charlier, J.-C. Three-dimensional massless dirac fermions in carbon schwarzites. Physical Review B 90, 125434 (2014).

Rosato, V., Celino, M., Benedek, G. & Gaito, S. Thermodynamic behavior of the carbon schwarzite fcc (c36)2. Physical Review B 60, 16928–16933 (1999).

Park, N. et al. Magnetism in all-carbon nanostructures with negative gaussian curvature. Physical Review Letters 91, 237204 (2003).

Townsend, S. J., Lenosky, T. J., Muller, D. A., Nichols, C. S. & Elser, V. Negatively curved graphitic sheet model of amorphous carbon. Physical Review Letters 69, 921–924 (1992).

O’Keeffe, M., Adams, G. B. & Sankey, O. F. Predicted new low energy forms of carbon. Physical Review Letters 68(15), 2325–2328 (1992).

Szefler, B. & Diudea, M. V. Polybenzene revisited. Acta Chimica Slovenica 59(4), 795–802 (2012).

Diudea, M. V., Stefu, M., John, P. E. & Graovac, A. Generalized operations on maps. Croatica Chemica Acta 79, 355–362 (2006).

Diudea, M. V. Nanoporous carbon allotropes by septupling map operations. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 45, 1002–1009 (2005).

Diudea, M. V. Covering forms in nanostructures. Forma (Tokyo) 19(3), 131–163 (2004).

Yang, H., Baig, A. Q., Khalid, W., Farahani, M. R. & Zhang, X. M-Polynomial and topological indices of benzene ring embedded in P-type surface network. Journal of Chemistry 2019, 7297253 (2019).

Ahmad, A. On the degree-based topological indices of benzene ring embedded in P-type-surface in 2D network. Hacettepe Journal of Mathematics and Statistics 47(1), 9–18 (2018).

Ahmad, A., Elahi, K., Hasni, R. & Nadeem, M. F. Computing the degree-based topological indices of line graph of benzene ring embedded in P-type surface in 2D network. Journal of Information and Optimization Sciences 40(7), 1511–1528 (2019).

Feng, X., Mu, H., Xiang, Z., & Cai, Y. Theoretical investigation of negatively curved \(6\cdot8^2\)D carbon based on density functional theory. Computational Materials Science 171, 109211 (2020).

Arockiaraj, M., Clement, J. & Balasubramanian, K. Topological indices and their applications to circumcised donut benzenoid systems, kekulenes and drugs. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds 40(2), 280–303 (2020).

Prabhu, S., Murugan, G., Arockiaraj, M., Arulperumjothi, M. & Manimozhi, V. Molecular topological characterization of three classes of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Journal of Molecular Structure 1229, 129501 (2021).

Radhakrishnan, M., Prabhu, S., Arockiaraj, M. & Arulperumjothi, M. Molecular structural characterization of superphenalene and supertriphenylene. International Journal of Quantum Chemistry 122(2), e26818 (2022).

Prabhu, S., Murugan, G., Cary, M., Arulperumjothi, M. & Liu, J. B. On certain distance and degree-based topological indices of zeolite LTA frameworks. Materials Research Express 7, 055006 (2020).

Arockiaraj, M., Liu, J. B., Arulperumjothi, M. & Prabhu, S. On certain topological indices of three-layered single-walled titania nanosheets. Combinatorial Chemistry & High Throughput Screening 25(3), 483–495 (2022).

Saravanan, B., Prabhu, S., Arulperumjothi, M., Julietraja, K. & Siddiqui, M. K. Molecular structural characterization of supercorenene and triangle-shaped discotic graphene. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds 43(3), 2080–2103 (2023).

Prabhu, S. et al. Computational analysis of some more rectangular tessellations of kekulenes and their molecular characterizations. Molecules 28(18), 6625 (2023).

Klav\(\check{z}\)ar, S., M. Nadjafi-Arani, Cut method: Update on recent developments and equivalence of independent approaches. Current Organic Chemistry 19, 348–358 (2015).

Manuel, P., Rajasingh, I. & Arockiaraj, M. Total-Szeged index of \(\text{ C}_4\)-nanotubes, \(\text{ C}_4\)-nanotori and dendrimer nanostars. Journal of Computational and Theoretical Nanoscience 10, 405–411 (2013).

Arulperumjothi, M., Prabhu, S., Liu, J. B., Rajasankar, P. Y. & Gayathri, V. On counting polynomials of certain classes of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds 43(5), 4768–4786 (2023).

Prabhu, S. et al. On counting polynomials of supercoronenes and triangle-shaped discotic graphene. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds 44(5), 3243–3271 (2024).

Klavžar, S. On the canonical metric representation, average distance, and partial Hamming graphs. European Journal of Combinatorics 27(1), 68–73 (2006).

Klavžar, S., Gutman, I. & Mohar, B. Labeling of benzenoid systems which reflects the vertex distance-relations. Journal of Chemical Information and Computer Sciences 35(3), 590–593 (1995).

Gutman, I. The energy of a graph. Ber. Math. Stat. Sekt. Forschungszentrum Graz. 103, 1–22 (1978).

Gutman, I. et al. Estimating and approximating the total \(\pi\)-electron energy of benzenoid hydrocarbons. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung A 55(5), 507–512 (2000).

Greeni, A. B., Kalaam, A. R. A. & Arockiaraj, M. Predicting graph energy and entropy analysis of pent-heptagonal nanomaterials: Insights from regression models using generalized reverse degree-sum topological indices. Materials Today Communications 41, 110229 (2024).

Stevanović, L., Brankov, V., Cvetković, D., Simić, S. newGRAPH, A fully integrated environment used for research process in graph theory, http://www.mi.sanu.ac.rs/ newgraph/index.html, (2021).

Bloom, G.S., Kennedy, J.W. & Quintas, L.V. Some problems concerning distance and path degree sequences, In: Borowiecki, M., Kennedy, J.W., Syslo, M.M. (eds) Graph Theory. Lecture Notes in Mathematics, vol 1018. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Redzepovic, I., Furtula, B. & Gutman, I. Relating total \(\pi\)-electron energy of benzenoid hydrocarbons with HOMO and LOMO energies. MATCH Communications in Mathematical and in Computer Chemistry 84(1), 229–237 (2020).

Balasubramanian, K. Cas scf/ci calculations on \(\text{ Si}_4\) and \(\text{ Si}_4^+\). Chemical Physics Letters 135(3), 283–287 (1987).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Methodology, S.P., M.A., M.A. and S.M.P. and; validation, X.Z., S.P. and V.M.; formal analysis, M.A., M.A. and S.M.P. and V.M.; investigation, X.Z., S.P. and V.M.; resources, X.Z., S.P., S.M.P. and V.M.; visualization, M.A. and M.A.; supervision, M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the current version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Prabhu, S., Arulperumjothi, M. et al. Distance based topological characterization, graph energy prediction, and NMR patterns of benzene ring embedded in P-type surface in 2D network. Sci Rep 14, 23766 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75193-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75193-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

On computing extended graph energies and their thermodynamic properties for benzenoid hydrocarbons

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

A dynamic programming algorithm for generating chemical isomers based on frequency vectors

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Topological information entropy and spectral energy analysis in aminal-linked covalent organic frameworks

Scientific Reports (2025)