Abstract

The real juncture between corrugated steel webs (CSWs) and flanges follows a multi-segmented line, distinct from that of flat steel webs. Classic methods may yield significant deviations in predicting the elastic global shear buckling capacity of CSWs of various scales due to their failure to consider real boundary constraints. Therefore, a universally applicable formula for calculating the elastic critical global shear buckling stress of CSWs, which accounts for real boundary conditions, is proposed. This formula is pertinent to both large-scale engineering CSWs and small-scale testing CSWs. This study commenced with a comprehensive reassessment of the elastic global shear buckling calculation method. Subsequently, the influence of geometric parameter ratios on the elastic critical global buckling stress was examined. The primary parameter was identified and employed to improve the global buckling coefficient. The proposed calculation method was validated using different corrugation configurations, including 1000-type, 1200-type, 1600-type, 1800-type, and 2000-type CSWs, as well as other CSWs used in experimental settings. These results were compared with those obtained from other reference methods. Findings indicate that the accuracy of the classic theoretical method is affected by variations in both boundary conditions and geometric dimensions due to the constraint effect of real boundary conditions. Under the real boundary conditions, the elastic critical global shear buckling stress of CSWs with simply supported boundary conditions is close to that of CSWs with consolidated boundary conditions. The ratio of web height to corrugation depth primarily affects the elastic global shear buckling capacity, which decreases as the ratio increases. The Easley formula can be modified based on the web height to corrugation depth ratio. Comparisons of numerous numerical and theoretical results reveal that the proposed calculation method exhibits commendable computational precision. In comparison to alternative formulas, the proposed method demonstrates enhanced consistency for calculating CSWs with varying geometric dimensions and boundary conditions, thereby demonstrating its favorable applicability. These conclusions provide valuable reference for the shear design of CSWs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Corrugated steel webs (CSWs) are extensively utilized in bridges1,2,3, buildings4,5,6, and culverts7,8 due to their superior shear buckling strength and out-of-plane stiffness. As the structural span increases, the height of CSWs also increases, making global shear buckling a critical design consideration. Existing methods typically rely on orthotropic plate theory to calculate the elastic critical global shear buckling stress of CSWs. However, these methods do not account for the three-dimensional spatial constraint effects induced by the corrugation configuration of CSWs. For certain specific parameters of CSWs, the traditional theoretical calculations may be overly conservative, thereby diminishing the economic benefits of composite girder bridges with CSWs. For instance, the Nanfeihe Bridge in China, which spans 153 m, employed thicker CSWs to avert global shear buckling failure. The maximum height of these CSWs is 6.35 m, and the maximum thickness is 34 mm. Further increasing the thickness is not feasible due to economic and manufacturing constraints. A more accurate calculation formula can help reduce costs and improve the span of composite beam bridges with CSWs. Furthermore, existing methods fail to provide accurate calculations for both large-scale CSWs in engineering applications and small-scale CSWs in laboratory settings, due to significant variations in geometric parameters. Consequently, it is imperative to develop an elastic global buckling calculation method that incorporates the effects of spatial boundary constraints and accommodates variations in geometric dimensions. Such a method would significantly enhance the application of CSWs in long-span structures.

In recent years, scholars have conducted extensive research on the static performance9,10,11,12, fatigue performance13,14, and fire performance15,16 of CSWs. Shear performance, a critical aspect of static performance, has been studied in various types of CSWs, including equal-section CSWs17,18,19, variable-section CSWs20,21, curved CSWs22,23 and stiffened CSWs24. These investigations cover a broad range of topics, from the mechanisms of shear failure to the effects of welding and corrosion damage on shear performance. The elastic shear buckling of CSWs includes local buckling25, global buckling26 and interactive buckling27, and is studied using both theoretical and numerical methods. For elastic global shear buckling, research has evolved from traditional theoretical formulas to methods that incorporate real boundary conditions. Easley and McFarland28 utilized orthotropic anisotropic plate theory to develop a formula for determining the elastic critical global buckling stress of CSWs. Nie et al.29 derived a formula for the elastic critical global buckling stress based on energy principles, demonstrating that the effect of constraints in the direction of weak bending stiffness of CSWs can be neglected. Hassanein and Kharoob30 utilized finite element models to analyze the elastic global buckling of CSWs under real boundary conditions. Their findings revealed that the elastic critical shear buckling stress of CSWs with consolidated boundaries is comparable to that of CSWs with simply supported boundaries. Furthermore, under real boundary conditions, the ratio of the critical buckling stress of CSWs with simply supported boundary conditions to that under consolidated boundary conditions is significantly higher than the ratio predicted by the orthotropic plate theory. Wang et al.31 developed an elastic shear buckling calculation formula tailored for four types of large-scale CSWs: the 1000-type, 1200-type, 1600-type, and 1800-type. This formula accounts for the real boundary constraints of large-scale CSWs and lacks validation for small-scale CSWs. It is noteworthy that the boundary constraints of CSWs differ from those of traditional flat steel webs. There is a paucity of elastic critical global shear buckling stress calculation formulas that consider real boundary conditions and are suitable for both large-scale CSWs used in engineering applications and small-scale CSWs used in testing.

The juncture between traditional flat steel webs and flanges is linear, whereas the juncture between CSWs and flanges follows a multi-segmented line. This corrugation configuration results in a spatial three-dimensional boundary for CSWs. Due to this difference, traditional plate theory cannot be directly applied to calculate the boundary constraint effects of CSWs. Existing orthotropic anisotropic plate theories are inadequate in accurately considering these real constraint effects. Finite element method-based fitting formulas are often used for specific types of CSWs but cannot be generalized to CSWs with varying parameter proportions.

To address these limitations and develop a widely applicable calculation method for elastic global shear buckling capacity, this study focuses on equal-section CSWs. Initially, the relationship between the ratio of geometric parameters and the elastic critical global shear buckling stress is analyzed using numerical methods, leading to the identification of the primary influencing parameters. Subsequently, the real boundary constraint effects and the accuracy of traditional orthotropic plate calculation methods are examined. Based on these findings, modifications are made to Easley’s elastic global shear buckling stress calculation formula. Finally, the modified formula is validated and compared with existing formulas by assessing the 1000-type, 1200-type, 1600-type, 1800-type, and 2000-type CSWs used in engineering, as well as certain CSWs employed in laboratory settings.

Theoretical methods

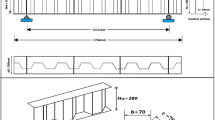

The classic approach considers the CSW as an orthotropic anisotropic plate, utilizing orthotropic anisotropic plate theory to determine the elastic critical global shear buckling stress. The formula for elastic critical global shear buckling stress, established by Easley32, is extensively employed and effectively illustrates the mechanical relationship between the primary parameters influencing elastic global shear buckling capacity, as depicted in Eq. (1). In this equation, kG represents the global buckling coefficient, which is assigned 36 for simply supported boundary conditions and 68.4 for consolidated boundary conditions29,32. Nonetheless, this formula does not accurately account for the real boundary constraints imposed by the corrugation configuration. Consequently, more precise formulas need to be developed from Eq. (1), incorporating spatial boundary constraints and accommodating various sizes of CSWs. Figure 1 presents a schematic diagram of CSWs.

where \(\tau\) is the elastic critical global shear buckling stress; kG is the global buckling coefficient; t is the thickness of CSWs; E is the elastic modulus of the steel; h is the height of the web; b is the parallel fold width; c is the inclined fold width; d is the horizontal projection of the inclined fold width; e is the corrugation depth; \(\alpha\) is the corrugation angle.

In practice, CSWs experience spatial boundary constraints that are distinct from those of flat steel webs. Even under simply supported boundary conditions, these spatial constraints limit the free rotation of CSWs. Wang et al.31 has derived formulas for calculating the elastic critical buckling stress for large-scale CSWs of types 1000, 1200, 1600, and 1800, based on extensive numerical analysis, as presented in Eq. (7). This equation takes into account the real boundary conditions. However, the applicability of this formula needs to be verified for small-scale CSWs in laboratory settings. The buckling coefficient limits are not specified. When the geometric parameter ratios deviate significantly from those typical of CSWs commonly used in engineering, excessively low buckling coefficients may result. To address this, the lower limits of the buckling coefficients in Eqs. (8) and (9) are set at 36, based on the buckling coefficients of a simply supported orthotropic anisotropic plate.

where \(k_{G}^{\prime}\) is obtained by Eq. (8) for CSWs with simply supported boundary conditions, and is obtained by Eq. (9) for CSWs with consolidated boundary conditions.

Numerical methods

Geometric deviations and welding residual stresses can cause some variability in the experimental results of the global shear buckling of CSWs. Additionally, spatial geometric boundaries complicate theoretical derivations. Therefore, the elastic shear buckling capacity of CSWs considering the real boundary juncture between CSWs and flanges is typically studied using the finite element method. Refer to the finite element buckling analysis method of CSWs, the CSW is simulated using ANSYS finite element package31,33,34. The SHELL181 four-node shell element is used to simulate the CSW with an elastic modulus of 206 GPa and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.3, as shown in Fig. 2. For simply supported boundary conditions on all four edges, the translation degrees of freedom in the z-direction and the x-direction are constrained on the AB side and the DC side, the translation degrees of freedom in the z-direction and the y-direction are constrained on the AD side, and the translation degree of freedom in z-direction is constrained on the BC side. The translational constraint for fully consolidated boundary conditions on all four edges are the same as that for simply supported boundary conditions, with the exception that rotational constraints are additionally imposed. Specifically, rotational constraints about the x-axis are applied at the edges AB and DC, while rotational constraints about the y-axis are applied at the edges AD and BC. For CSWs with simply supported or consolidated boundary conditions, a uniformly distributed vertical load is applied on the BC edge. The effect of the loading point position on the critical buckling stress is negligible when the ratio of edge AB/edge BC is greater than 229. Moreover, after trial calculation, when there are six elements in the length of the straight section of CSWs, a more accurate numerical result can be obtained and the calculation efficiency can be taken into account. The typical global buckling failure mode of CSWs is shown in Fig. 3.

To validate the accuracy of the numerical model, the critical buckling stress derived from the aforementioned numerical modeling method was compared with the numerical results calculated by Hassanein and Kharoob30. Table 1 provides a comparison of the numerical results. It is noteworthy that the finite element calculation model utilized in Table 1 employs the material parameters provided by Hassanein and Kharoob30 to eliminate discrepancies in calculation results attributable to material differences. The average ratio is 1.00 and the standard deviation (SD) is 0.02. The numerical results predicted in the paper agree well with the results calculated by Hassanein and Kharoob30. In addition, the critical shear buckling stress of CSWs calculated using the above numerical method is similar to the finite element fitting formula results predicted by Wang et al.31. The mean and SD also closely match the results predicted by Wang et al.31, indicating the accuracy of the numerical method, as shown in Figs. 11b and 12b. Detailed analysis can be found in the verification of the proposed calculation method section. The elastic buckling stress of CSWs can be predicted by the proposed finite element analysis method.

Finite element analysis

Parameter analysis

Geometric foundation design parameters of CSWs include web height (h), web thickness (t), corrugation depth (e), parallel fold width (b) and horizontal projection of inclined fold width (d). The elastic global buckling capacity of CSWs was investigated by varying the geometric foundation design parameters for the corrugation configurations30,35,36 of 1600-type, 2000-type and Hassanein-type CSWs. The geometric foundation design parameters of each model are detailed in Table 2. Each type of CSWs was divided into five groups based on the geometric foundation design parameters, with each group consisting of six models. The parameter groups of different types of CSWs are represented by A1-A5, B1-B5, and C1-C5. For example, the models in the first group of design parameters are labeled A1, B1, and C1.

To ensure that the analysis results are applicable to both large-scale engineering CSWs and small-scale laboratory CSWs, the design parameters were examined in terms of their ratios: web height to corrugation depth (h/e), corrugation depth to web thickness (e/t), parallel fold width to inclined fold width (b/c), and the corrugation angle (\(\alpha\)). Referring to the parameter ratio of CSWs in the engineering and CSWs in the laboratory, the parameter variation range for the global shear buckling analysis is as follows: (1)\(0.5 \le b/c \le 2\); (2)\(27^\circ \le \alpha \le 45^\circ\); (3)\(7 \le e/t \le 25\); (4) \(20 \le h/e \le 130\). It is important to note that, to ensure the applicability of the analysis results to various sizes of CSWs, the web height in Table 2 has been appropriately expanded. This adjustment aims to guarantee that the parameter ratio analysis results are valid for both large-scale and small-scale CSWs. The parameter ratios of CSW models in the subsequent calculation method validation are also within the above range. In Table 2, the first, second, and fourth groups were used for analyzing the relationships between h/e、e/t、b/c, and the critical global shear buckling stress. For the third and fifth groups, alterations in the basic parameters result in variations in multiple parameter ratios. The fifth group which exhibits less parameter coupling, will be used to analyze the influence of parameter \(\alpha\). The third group, characterized by more parameter ratio coupling, will be employed for subsequent statistical analysis.

Figure 4 illustrates the relationship between the parameter ratios and the critical global shear buckling stress of CSWs with simply supported boundary conditions on all four edges. To facilitate the analysis of different types of CSWs, the vertical axis represents the ratio of the critical global shear buckling stress (\(\tau_{1}\)) to the average critical global shear buckling stress (\(\tau_{{\text{e}}}\)) of the six models in each group. The horizontal axis represents the parameter ratios. For different types of CSWs, the relationship between these parameter ratios and the critical global shear buckling stress is consistent: the critical shear buckling stress decreases with increasing h/e and e/t, and increases with increasing b/c. Furthermore, variations in parameter \(\alpha\) and the b/c ratio result in only slight changes in the \(\tau_{1} /\tau_{{\text{e}}}\) ratio, indicating that \(\alpha\) and b/c exert minimal influence on the critical shear buckling stress. Notably, when the h/e ratio changes the variation range of \(\tau_{1} /\tau_{{\text{e}}}\) is between 0 and 3. This variation is substantially higher compared to the influence exerted by other parameter ratios on the critical global shear buckling stress.

Additionally, for CSWs with fully consolidated boundary conditions on all four edges, the relationship between the parameter ratios and the critical global buckling stress remains analogous to that observed in CSWs with simply supported boundary conditions on all four edges. As illustrated in Fig. 5, the h/e ratio continues to be the most significant influencing parameter under the condition as well. This consistency underscores the critical role of the h/e ratio in determining the global shear buckling capacity of CSWs across different support conditions.

Discussion on boundary constraint effect

Figure 6 examines the constraint effect of the real boundary conditions of CSWs. In Fig. 6, \(\tau_{{\text{s}}}\) represents the elastic critical global shear buckling stress for the simply supported boundary condition, while \(\tau_{{\text{F}}}\) denotes the elastic critical global shear buckling stress for the consolidated boundary condition. It is evident from Fig. 6 that the ratio of \(\tau_{{\text{s}}} /\tau_{{\text{F}}}\) under the real boundary condition ranges between 0.8 and 1. This indicates that, due to the spatial boundary constraint, the constraint effect of the simply supported boundary condition for CSWs is comparable to that of the consolidated boundary condition. In contrast, the traditional orthotropic anisotropic theory yields a ratio of 0.53, as it fails to account for the spatial constraint effect.

Improved Easley formula

The ratio of h/e significantly influences the elastic global shear buckling capacity. Figures 7 and 8 show the relationship between the accuracy of the traditional calculation method and the ratio of h/e. In these figures, \(\tau_{1}\) denotes the numerical results, and \(\tau_{2}\) represents the theoretical results calculated using Eq. (1). For CSWs with simply supported boundary conditions on all four edges, the theoretical results are generally lower than the numerical results. As the h/e ratio increases, the theoretical results gradually approach the numerical results, as illustrated in Fig. 7. Conversely, for CSWs with fully consolidated boundary conditions on all four edges, the theoretical results are generally higher than the numerical results. As the h/e ratio decreases, the theoretical results converge towards the numerical results, as shown in Fig. 8.

The discrepancy between theoretical and numerical results arises because Eq. (1) simplifies the CSW to an orthotropic plate and the boundary condition to a two-dimensional plate boundary. In reality, the boundary of CSWs is three-dimensional. The spatial boundary constraints imply that the rotation of CSWs under simply supported boundary conditions is also restricted, a factor that the traditional formula fails to accurately account for. Given that the influence of the h/e ratio on the elastic global buckling capacity is much more significant than that of other parameter ratios, it is feasible to modify the existing theoretical calculation method by using the h/e ratio as the primary parameter. By performing statistical regression on the data in Figs. 7 and 8, a correction formula can be established, as shown in Eq. (10).

where kG1 is the boundary constraint correction factor.

For CSWs with simply supported boundary conditions on all four edges, the boundary constraint correction factor can be obtained as:

For CSWs with consolidated boundary conditions on all four edges, the boundary constraint correction factor can be obtained as:

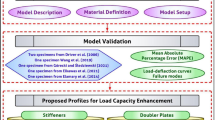

Verification of the proposed calculation method

To verify the accuracy of Eq. (10), both engineering CSWs and certain testing CSWs were employed. The corrugation configurations31,35,36 for 1000-type, 1200-type, 1600-type, 1800-type and 2000-type CSWs were determined. The parameter range for CSWs in engineering is detailed in Table 3, which lists the common parameters used for bridges with CSWs that experience global shear buckling, with appropriate extensions. Generally, as the span of the bridge increases, a larger type of CSW and a higher web are utilized. Given that 1800-type and 2000-type CSWs are relatively new with few engineering cases, the maximum height for these two types has been increased by 2 m compared to that of the 1600-type CSW. Most CSWs within this range exhibited global shear buckling failure. Moreover, only models that experienced global buckling failure were utilized for the calculation method verification. For CSWs in laboratory, the corrugation configurations33,37,38 were analyzed. The thickness and height of the webs were adjusted to ensure the global shear buckling failure. The detailed parameters are provided in Table 4.

Equations (1), (7) and (10) are employed to calculate the elastic global shear buckling capacity of CSW models for both engineering applications and experimental tests. These formulas are recommended by Easley32, Wang et al.31, and this paper respectively. Figures 9, 10, 11, and 12 show the comparison between the theoretical results and the numerical results. The average value and SD of the ratio between the theoretical results and the finite element results are shown in Table 5. When applying different formulas to calculate the elastic critical global shear buckling stress of CSWs of varying geometric dimensions and boundary conditions, differences in accuracy and discrepancies are observed. The average ratio of theoretical results derived from the Easley formula to those obtained from finite element analysis ranges from 0.61 to 1.53, with a SD between 0.05 and 0.09. Utilizing the formula proposed by Wang et al.31, the average ratio of theoretical results to numerical results lies between 0.83 and 1.05, with a SD ranging from 0.01 to 0.05. For the proposed formula, the average ratio of theoretical results to numerical results spans from 0.95 to 1.01, with an SD between 0.04 and 0.06.

For the engineering CSWs with consolidated boundary conditions and testing CSWs with simply supported boundary conditions, the theoretical results calculated by Eq. (1) are in good agreement with the numerical results, as shown in Figs. 9a and 12a. However, for other cases of CSWs, the theoretical results calculated by Eq. (1) deviate from the numerical results. This discrepancy arises because the Easley formula’s accuracy varies markedly with changes in boundary conditions and geometric dimensions, due to its inability to account for real spatial boundary constraint effects. The elastic global buckling capacity of large-sale CSWs in the engineering can be well predicted by the formula proposed by Wang et al.31. However, there is a certain deviation in predicting the critical shear buckling stress of CSWs in the laboratory, as shown in Figs. 9b and 10b. Since Eq. (7) is mainly used to calculate the large-scale CSWs in the engineering, its applicability is limited when the parameter ratios of testing CSWs differ significantly from those of engineering CSWs, resulting in an inability to accurately calculate elastic critical global shear buckling stress. The formula proposed in this paper provides similar calculation accuracy for both large-scale CSWs in the engineering and small-size CSWs in the laboratory. The accuracy is consistent regardless of changes in geometric parameters and boundary conditions, demonstrating the formula’s good applicability. Therefore, it can be used to predict the elastic global shear buckling capacity of CSWs. Additionally, when the parameter variation falls within the range specified in the parameter analysis section, the proposed formula can accurately calculate the elastic critical global shear buckling stress. For other, less common parameter ranges of CSWs, further verification of the formula’s accuracy is necessary.

In general, the elastic global buckling capacity of CSWs with different sizes and boundary conditions can be calculated using Eq. (1) for simply supported boundary conditions, providing a conservative estimate. The formula proposed by Wang et al.31 is suitable for large-scale CSWs in engineering. The formula presented in this paper effectively predicts the elastic global buckling capacity for both large-scale engineering CSWs and small-scale testing CSWs.

Conclusions

Numerical models were employed to investigate the calculation method for the elastic critical global shear buckling stress of CSWs with varying geometric dimensions and boundary conditions. A modified Easley formula was proposed to predict this stress for both large-scale engineering CSWs and small-scale testing CSWs, taking real boundary conditions into account. The primary research conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

Due to the spatial boundary constraint, the constraint effect of the simply supported boundary condition for CSWs is comparable to that of the consolidated boundary condition. The classic calculation method fails to accurately account for the real boundary constraint effect for CSWs with different sizes and boundary conditions.

-

(2)

The elastic critical global shear buckling stress of CSWs is influenced by the ratios of web height to corrugation depth, corrugation depth to web thickness, parallel fold width to inclined fold width, and the corrugation angle. Among these, the ratio of web height to corrugation depth is the most significant factor.

-

(3)

Using the ratio of web height to corrugation depth as the primary variable, the Easley formula has been modified. The proposed formula can be used to calculate the elastic critical global shear buckling stress of large-scale CSWs in engineering applications, as well as the elastic global shear buckling stress of small-scale CSWs in laboratory settings. This formula demonstrates an improved level of accuracy and consistency.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chen, Y., Dong, J., Tong, Z., Jiang, R. & Yue, Y. Flexural behavior of composite box girders with corrugated steel webs and trusses. Eng. Struct. 209, 110275 (2020).

Wang, S., Zhang, K., Zhang, Y. & Liu, Y. Shear failure mechanism of local buckling-dominated large-scale corrugated steel web. Thin-Walled Struct. 182, 110279 (2023).

Deng, W., Liu, D., Xiong, Y. & Zhang, J. Experimental study on asynchronous construction for composite bridges with corrugated steel webs. J. Constr. Steel. Res. 157, 93–102 (2019).

Wen, Z., Wei, X., Xiao, L. & Dai, L. Shear performance of corrugated steel webs with local uniform defects. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn.https://doi.org/10.1142/S021945542250153X (2022).

Deng, H., Shao, Y. & Hassanein, M. F. Experimental shear testing of small-scale corrugated web girders used in conventional buildings. J. Constr. Steel. Res. 189, 107086 (2022).

Wang, T. & Ma, J. Shear Buckling stress and normalized shear strength of trapezoidal corrugated steel web. J. Build. Eng. 57, 104807 (2022).

Kearns, O., Moore, I. D. & Hoult, N. A. Measured responses of a corrugated steel ellipse culvert at different cover depths. J. Bridge Eng.https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)BE.1943-5592.0001635 (2020).

Sun, K. et al. Analysis and prediction of mechanical characteristics of corrugated plate as primary support in tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 111, 103845 (2021).

Sause, R. & Braxtan, T. N. Shear strength of trapezoidal corrugated steel webs. J. Constr. Steel. Res. 67, 223–236 (2011).

Hlal, F. & Al-Emrani, M. Flange buckling in stainless-steel corrugated webs I-girders under pure bending: Numerical study. J. Constr. Steel. Res. 208, 108031 (2023).

He, J., Wang, S., Liu, Y., Lyu, Z. & Li, C. Mechanical behavior of a partially encased composite girder with corrugated steel web: Interaction of shear and bending. Engineering 3, 806–816 (2017).

Zhu, Y. et al. Torsional repair of damaged single-box multi-cell composite box-girder with corrugated steel webs using CFRP. Part II: Theoretical investigation. Compos. Struct. 301, 116204 (2022).

Yang, T. et al. Fatigue performance of stud connectors in joints between top slabs and steel girders with corrugated webs subjected to transverse bending moments. Eng. Struct. 310, 118132 (2024).

Liu, X., Xiong, Z., Liu, Y., Li, J. & Liang, C. Optimization and fatigue assessment of girders with large-dimension corrugated steel webs. Structures 64, 106619 (2024).

Zhou, M. & Peng, X. Shear behavior of prismatic and tapered prestressed concrete girders with corrugated steel webs exposed to vehicle fire. Eng. Struct. 308, 118004 (2024).

Khan, M. A. et al. Response of restrained stainless steel corrugated web beams at elevated temperature. Structures. 41, 668–683 (2022).

Alikhanifard, M. A., Rahai, A. R. & Tehrani, P. A new shear strength model for steel corrugated web girders. J. Constr. Steel. Res. 197, 107457 (2022).

Zhao, Z. et al. Shear capacity of corrugated steel plates with a random corrosion damage. Thin-Walled Struct. 193, 111264 (2023).

Kollár, D. & Kövesdi, B. Welding simulation of corrugated web girders-Part 1: Effect of manufacturing on residual stresses and imperfections. Thin-Walled Struct. 146, 106107 (2020).

Ji, W. & Liu, X. Analysis of the shear buckling strength of variable-section corrugated steel webs. Ksce J. Civ. Eng. 25(08), 1–17 (2021).

Zhao, P., Chen, C., Shao, X. & Rong, X. Shear stress at joint of prefabricated-composite box girders with corrugated steel webs. J. Constr. Steel. Res. 212, 108301–108307 (2024).

Eldib, A. H. Shear buckling strength and design of curved corrugated steel webs for bridges. J. Constr. Steel. Res. 65, 2129–2139 (2009).

Yossef, N. M. A new approach to estimate the shear strength of curved corrugated steel webs. Structures 24, 400–414 (2020).

He, J., Wang, S., Liu, Y., Wang, D. & Xin, H. Shear behavior of steel i-girder with stiffened corrugated web. Part II: Numerical study. Thin-Walled Struct. 147, 106025 (2020).

Sebastiao, L. & Papangelis, J. Elastic local shear buckling of beams with sinusoidal corrugated webs. Structures 54, 684–692 (2023).

Kim, K. & Park, S. Analysis of shear buckling for sinusoidal corrugated web beam. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mech. 51, 6863–6880 (2023).

Hosseinzadeh, L., Mofid, M., Aziminejad, A. & Emami, F. Elastic interactive buckling strength of corrugated steel shear wall under pure shear force. Struct. Des. Tall. Spec. 26(8), 1357 (2017).

Easley, J. T. & McFarland, D. E. Buckling of light-gage corrugated metal shear diaphragms. J. Struct. Div. 95(7), 1497–1516 (1969).

Nie, J. G. & Tang, L. Global shear buckling of corrugated steel plates with edges elastically restrained against rotation. Eng. Mech. 03, 1–7 (2008).

Hassanein, M. F. & Kharoob, O. F. Behavior of bridge girders with corrugated webs: (I) Real boundary condition at the juncture of the web and flanges. Eng. Struct. 57, 554–564 (2013).

Wang, S., Zhang, Y., Luo, T. & Liu, Y. Elastic critical shear buckling stress of large-scale corrugated steel web used in bridge girders. Eng. Struct. 244, 112757 (2021).

Easley, J. T. Buckling formulas for corrugated metal shear diaphragms. J. Struct. Div. 101(07), 1403–1417 (1975).

Nie, J. G., Zhu, L. & Tang, L. Shear strength of trapezoidal corrugated steel webs. China Civ. Eng. J. 46(06), 97–109 (2013).

Tohamy, A. S. et al. Efficiency of web cutouts for steel plate girders with corrugated webs versus flat webs under shear loading. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 48(4), 5215–5228 (2023).

CJJ/T 272-2017, Technical Standard for Composite Girder Bridges with Corrugated Steel Webs (2017).

JTT 784-2022, Corrugated Steel Webs in Composite Structure Bridge (2022).

Elgaaly, M., Hamilton, R. W. & Seshadri, A. Shear strength of beams with corrugated webs. J. Struct. Eng. 122(4), 390–398 (1996).

Li, L. F., Hou, L. C. & Sun, J. C. Research on shear mechanical property of corrugated steel webs. J. Hunan Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 42(11), 56–63 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the financial support from Fujian Natural Science Foundation (2023J05056 and 2023J011104) and Fujian Educational Research Project for Young and Middle-aged Teachers (JAT220242).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z. T.:Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-Original Draf; K. S.: Investigation, Writing—Review and Editing; Y. L.: Numerical Analysis; J. D.: Formal Analysis; B. L.: Data Curation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tong, Z., Shen, K., Li, Y. et al. Modified Easley formula for elastic critical global shear buckling stress of corrugated steel webs considering real boundary conditions. Sci Rep 14, 24702 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75368-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75368-3