Abstract

Magnetoencephalography (MEG) provides crucial information in diagnosing focal epilepsy. However, dipole estimation, a commonly used analysis method for MEG, can be time-consuming since it necessitates neurophysiologists to manually identify epileptic spikes. To reduce this burden, we developed the automatic detection of spikes using deep learning in single center. In this study, we performed a multi-center study using six MEG centers to improve the performance of the automated detection of neuromagnetically recorded epileptic spikes, which we previously developed using deep learning. Data from four centers were used for training and evaluation (internal data), and the remaining two centers were used for evaluation only (external data). We used a five-fold subject-wise cross-validation technique to train and evaluate the models. A comparison showed that the multi-center model outperformed the single-center model in terms of performance. The multi-center model achieved an average ROC-AUC of 0.9929 and 0.9426 for the internal and external data, respectively. The median distance between the neurophysiologist-analyzed and automatically analyzed dipoles was 4.36 and 7.23 mm for the multi-center model for internal and external data, respectively, indicating accurate detection of epileptic spikes. By training data from multiple centers, automated analysis can improve spike detection and reduce the analysis workload for neurophysiologists. This study suggests that the multi-center model has the potential to detect spikes within 1 cm of a neurophysiologist’s analysis. This multi-center model can significantly reduce the number of hours required by neurophysiologists to detect spikes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magnetoencephalography (MEG) is an effective tool for the clinical analysis of epilepsy1,2. Neurophysiologists analyze abnormal signals (spikes, sharp waves, or polyspikes) obtained by MEG and consider the location of the epileptic lesion. The equivalent current dipole (ECD) estimation method is the primary method used for the clinical analysis of abnormal signals. This method estimates the abnormal signal source (i.e. ECD) by solving an inverse problem3. The ECD estimation method requires time and effort because the abnormal signals in the MEG sensor time series must be identified by visual inspection, and the sensor area related to those signals must be selected4. Multiple ECDs and the sizes and shapes of the clusters they compute should be obtained to make more accurate decisions5.

Recently, a deep learning (DL) approach has been proposed to decrease the time and effort required and increase detection accuracy. DL is an effective approach for analyzing images, text, and signals for classification, regression, or generation6,7,8,9,10,11. Studies have reported the use of DL not only in MEG but also in electroencephalography (EEG) for abnormal signal analysis. The epileptic MEG spikes detection algorithm based on a deep learning network (EMS-Net) was proposed to classify MEG signals as spike or non-spike12. SpikeNet has also been proposed to classify EEG signals as spike or non-spike13.This model demonstrated performance comparable to that of experts by applying a residual network that achieved success in an image classification task6. In addition to these two studies, various DL approaches have been proposed14,15,16. However, they are insufficient for reducing the time-consuming cost of the clinical work required to complete MEG testing, as most of these studies were limited to simply classifying whether there is a spike in a certain time window. Fully automated testing requires not only the classification of spikes but also the identification of the time and spatial distribution of spikes, which are indispensable for ECD estimation. Hence, we developed a DL-based algorithm to simultaneously estimate the time and sensor region of an anomalous wave using a single-center MEG dataset17. Furthermore, we developed post-processing ECD analyses sequentially performed after spike detection, allowing for the automation of a series of clinical epilepsy analysis procedures. These methods include ECD estimation, clustering, and quantification. These operations are fully automated.

When training the DL model, the quality and amount of data influence its performance. Data collection from the multicenter itself is not technically difficult. However, we must pay attention to the characteristic differences between the centers. This is because data variability increases when treating data obtained from different centers or with different measurement protocols18. Additionally, evaluation using an external dataset is important. In a systematic review, most DL algorithms demonstrated decreased performance on an external dataset in radiological diagnosis19. An EEG study on sleep stage scoring using DL also showed decreased performance on an external dataset20. MEG data are influenced by environmental noise or large moving magnetic objects such as cars, elevators, and even hospital beds21. These environmental properties differ between institutions. Therefore, to evaluate the performance of the DL model, validation using an external dataset is crucial for improving generalization performance using a multi-center dataset.

This study aimed to enhance the efficacy of the model by incorporating diverse spike shapes learned from MEG data gathered across various facilities. Additionally, we suggest augmentation techniques to normalize the variations in data characteristics across facilities. The model is evaluated in two ways: first, at the segment level, utilizing fixed-length segments utilized during the training phase; and second, via comparison with the outcomes of the neurophysiologist’s analysis of continuous data. To verify the generalizability of the model, its performance was assessed using data from facilities not utilized during the training phase.

Methods

Participants

In this study, we used clinical MEG data for epilepsy at six domestic centers equipped with MEG equipment manufactured by either Ricoh or Yokogawa Electric Corporation. No new MEG measurements of patients were performed for this study. Data procured from four centers (Osaka University Hospital, Osaka Metropolitan University Hospital, Tohoku University Hospital, and NHO Shizuoka Institute of Epilepsy and Neurological Disorders) served as internal data for training, whereas data obtained from two additional centers (Kumagaya General Hospital and Hokuto Hospital) were used solely for external evaluation. Table 1. presents a summary of the participant information. The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of Osaka University Hospital (No. 19484-5), Ethical Committee of Osaka Metropolitan University Graduate School of Medicine (No. 2020-033), Ethics Committee Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine (No. 2020-1-1065), Ethics Committee of National Epilepsy Center, NHO Shizuoka Institute of Epilepsy and Neurological Disorders (No.2020-01), Ethics Committee of Kumagaya General Hospital (No. 2020-41), and Ethics Committee of Hokuto Hospital (No.1077). The study complied with applicable ethical guidelines, including ethical approval, Declaration of Helsinki compliance, and institutional ethical guidelines; moreover, data from each institution were collected after anonymization. Additionally, informed consent was acquired from all participants in this study through an opt-out procedure. Specifically, the website of each facility divulged the subjects, purpose, significance, methodologies, materials, and information entailed in the study, along with the provision of said materials and information to external parties, conflict of interest considerations, research affiliation, and contact details. Patients were afforded the option to withdraw from the study to preempt any potential disadvantages. Internal and external datasets were used to evaluate the performance of the DL model in scenarios where data were already available and in a newly installed MEG environment. The total number of participants from the six centers was 1782 (714 males, 586 females, and 482 unknown individuals), with a median age of 25 years and a range of 0–95. The participants included those with various types of epilepsy, including focal, generalized, and complicated. Detailed information on the disease type of patients was only available for Center A, so it is included in Supplementary Table S1. For the other centers, we had to refer to the electronic medical records, but due to cost considerations, we were unable to obtain this information. Instead, we have listed the hospital functions for each center certified as of January 2024 below. Centers A, C, and D are designated as epilepsy support base hospitals by their prefectures. Institutions A, B, and D are comprehensive epilepsy specialist medical facilities accredited by the Japan Epilepsy Society. Institutions E and F are designated as regional medical care support hospitals by the prefectural government.

MEG measurement and preprocessing

Each participant was evaluated according to the epilepsy clinical examination protocol at each center. The focus of this study was on resting-state measurements. The resting-state MEG data included two types of scans: eyes open and eyes closed. In both cases, some centers instructed the patient to rest, while others did not. In some cases, sedation was applied based on the participant’s condition. Sampling frequencies varied between 500 and 10,000 Hz; low-pass filters between 100 and 500 Hz and high-pass filters between 0.1 and 3.0 Hz were employed, although some data were obtained unfiltered. Notch filters were occasionally used to exclude AC noise. The MEGs used at each center were of the all-head type equipped with either 160- or 200-channel axial gradiometers (MEGVision; Yokogawa Electric Corporation, Kanazawa, Japan and RICOH160-1; RICOH, Tokyo, Japan).

The MEG data recorded at each center were used to create the training dataset, which fundamentally adhered to the method described in a previous study17. The only difference from the previous method was the downsampling frequency rate. This was previously 1000 Hz, but 250 Hz was used in this study. This revision was made because the lower limit of the sampling frequency in the previous study was 1000 Hz, whereas in the present data, it was 500 Hz, and to decrease the complexity of the machine learning model by having fewer model parameters. In addition to this revision, the processing method employed was consistent with a previous study, which included the application of a 3–35 Hz bandpass filter characterized by a 2000-order finite impulse response employing a hamming window, coupled with a dual-pass filtering procedure. Among all the centers, only Center E employed dual signal subspace projection (DSSP)22 for noise reduction. Consequently, this study applied DSSP to Center E’s data only to ensure consistency in the spike detection conditions used by neurophysiologists. Regarding data in which spikes were detected by neurophysiologists, 512 time points centered on the spike time were extracted and registered as spike-positive segments, whereas for data without spikes, 512 time points were extracted every 3 s and registered as spike-negative segments. To learn the segmentation model, the correct answer masks were simultaneously recorded. The correct mask was of the same size as the extracted segment data and was created by setting the neurophysiologist-registered dipole time \(\pm 15\) timepoints to 1 for the selected sensor and 0 for all other timepoints. A correct mask was created by setting all values to 0 for spike-negative data. In the Yokogawa-Ricoh MEG system, a set of preliminary sensors has been implemented to maintain a consistent number of measurable sensors. Specifically, in the event of sensor malfunction, the constancy of the sensor count is ensured through the activation of a redundant sensor. Notably, the arrangement of sensors at each center exhibits fundamental dissimilarities. Therefore, to compensate for variations in sensor placement and the quantity of sensors, the sensor order was normalized, and the magnetic field values at positions where no sensor was placed were supplemented from the surrounding sensors. Experienced neurophysiologists (M.H.) selected spike-positive data to include only data with large typical amplitudes. The number of training datasets per institution is presented in Table 2. The number of spike-negative data points at Centers A and C was disproportionately large compared to the number of spike-positive data points; thus, they were randomly sampled. All segment data were visually observed by a neurophysiologist skilled in MEG analysis (M.H.), and data unsuitable for the study were excluded.

Data augmentation

Data augmentation was utilized to prevent overfitting when training the deep learning models23. In this study, four augmentation techniques were employed: cropping window, shifting sensor order, reverse phase, and mixing frequency. In the training iteration of the model, each augmentation is independently applied subsequent to the loading of data. In order to augment data diversity, each parameter is stochastically assigned for every data readout. The cropping window involves randomly selecting 256 timepoints from a 512-timepoint segment to ensure that the spike detection performance is not dependent on the relative time in the segment data. The shifting sensor order randomly rearranges the order of sensors. Given that temporal lobe epilepsy is relatively common in partial-onset epilepsy24, spikes are expected to be more prevalent in sensors close to the temporal lobe. Therefore, similar to the cropping window, shifting sensor order was applied to mitigate the sensor-order dependence of the spikes. The reverse phase flips the phase. The ECD model assumes that the dipole direction is inverted, thereby enhancing the data corresponding to cases in which the head is measured in a different direction during MEG testing. The mixing frequency was based on previous studies25,26, in which reference segment data were randomly selected from spike-negative data and combined with source segment data in the frequency domain. MEG data are susceptible to environmental magnetic fields22,27, and each center is expected to have unique frequency components. Biological data are also susceptible to individual differences, with frequency components at rest differing between young and elderly individuals28. Mixing frequency was introduced to reduce the impact of the environmental magnetic field and age group disparities.

Model training and evaluation

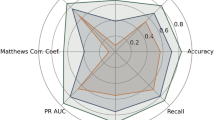

Figure 1 shows the pipeline used for model training and evaluation. The preprocessing and segmentation of continuous data are described in the preceding section. Five models were trained for each of the classification and segmentation networks, following a previous study17: a single-center model utilizing data from each of the four internal centers and a multi-center model employing data from all four centers. For the classification network, scSE-Module29, DropConnect Module30, and Dilated Convolution31 were applied to improve accuracy and generalization performance based on a 26-layer ResNet32. For the segmentation network, we also used DeepU-Net33, an extension of U-Net34. As in the previous study17, it has the same structure as the classification network, allowing the sharing of learned weights. When training the segmentation network, the weights of its encoder part were initialized using the weights of the trained classification network. A five-fold subject-wise cross validation was performed to assess the performance of the participants not used for training. Table 3. presents the parameters used during training. The participants included in each fold were the same for the multicenter and single-center models. The evaluation indices for the classification model comprised the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC-AUC), recall, precision, and specificity. The segmentation model was evaluated using the Dice index. The Dice index is a standard measure used in the evaluation of segmentation networks. It is calculated using the formula \(Dice\;Index=2\times |A \bigcap B| / (|A|+|B|)\) for a target region A and a estimated region B output by the segmentation network. Here, || denotes the number of elements contained in the regions, and \(\bigcap\) denotes common regions. The Dice Index is 1 when region A and region B are perfectly matched, and it is 0 when they have no common region. Those evaluation metrics were calculated with a calculation threshold of 0.5.

Training and evaluation pipeline. The MEG data acquired from each center was preprocessed and segmented. The internal segments were utilized to train classification and segmentation models. A single-center model was trained on data from a single center, whereas a multi-center model was trained on data obtained from multiple centers. The trained models were evaluated using both internal and external segment data. Subsequently, preprocessing was applied to the continuous data, and the trained single-center and mutli-center models were utilized to automatically detect spikes. Additionally, dipole analysis, sorting, and clustering were performed and compared with the results previously analyzed by neurophysiologists. For external data, a multi-center model was utilized to evaluate both segment and continuous data.

Subsequently, the segmentation model trained using the segmented data was employed for continuous data (typically 20–40 min) evaluation. The evaluation process was as described in a previous study17. First, the same preprocessing steps (3–35 Hz bandpass filter and 250 Hz downsampling) were applied during model training. Input data of the same size as that used during training were then cropped while overlapping the continuous data by 75% of the segment data length. The trained segmentation model was applied to each cropped input, and the resulting outputs were averaged. The output of the detection model is represented as a spike confidence map, with higher values for the sensors and times with greater spike confidence. A Gaussian filter (\(\sigma =15\) timepoints) was then applied to this two-dimensional certainty map, and the peak with a spike confidence greater than 0.5 was designated as the spike detection time. For the ECD, the spike duration was assumed to be 30 ms, and all the dipoles for \(\pm 7\) ms before and after the detection time, which corresponds to half of the 30 ms spike duration37, were calculated. Dipoles that were excessively mobile or local solutions in the ECD method were excluded from the analysis. Given that the equivalent current dipole method posits a singular current entity, the outcomes of the analysis prove to be unreliable in scenarios involving the concurrent presence of multiple signals or instances where the signal-to-noise ratio of spikes is suboptimal. In accordance with a previous study38 and standard clinical analytical practices, the following criteria were employed for exclusion: goodness-of-fit (GoF) equal to or exceeding 0.8, dipole intensity falling within the range of 50–1000 nAm, and the mean distance from the dipole’s center of gravity, as calculated continuously over time, being 2 cm or less. Ultimately, the dipole characterized by the highest intensity was duly recorded as the autonomously scrutinized dipole. Finally, the dipole time was selected as the time of the highest intensity when the signal-to-noise ratio of the spike and background brain activity was optimal. The dipole clusters were calculated using the density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN) method39 with parameters eps = 0.015 and minPts = 4 to evaluate the coherence of the dipole, which is also evaluated as the focus of epilepsy in real clinical practice. The evaluation index was calculated by comparing the time differences between the neurophysiologist’s manual analysis, spike detection, and dipole times. In the continuous data analysis of spike-negative cases, the number of false positives (FPs) per minute was evaluated. Additionally, the distance between the neurophysiologist’s dipole and the automatically detected dipole and the overlap of the dipole clusters that each constituted were obtained. Furthermore, dipole indices (GoF, intensity, and confidence volume40) were compared.

All implementations were performed in Python using an Ubuntu 18.04.3 LTS machine with an Intel Core i9-9900K CPU clocked at 3.60 GHz with 64 GB of RAM and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 Ti GPU. We measured the time required for the automatic analysis of continuous data when using this environment.

Results

Segment level evaluation

Spike classification and segmentation networks were trained using resting-state MEG segmentation data. The classification network was trained to determine the presence of spikes in the segmented data, whereas the segmentation network was trained to identify the exact time and sensors at which the spikes occurred. Table 4 lists the classification and segmentation results. The data from Centers E and F were used as external data and were not used to train the deep learning models. Data from other centers were used as internal data to train the deep learning models. A five-fold subject-wise cross-validation was utilized, with each evaluation metric indicating a five-fold mean value. The classification performance achieved by incorporating individual augmentations from the unaugmented training data is shown in Supplementary Table S2. The best classification performance was observed when all four augmentations were employed simultaneously. The evaluation metrics for segmentation, Dice+ and Dice-, represent the Dice index for spike-positive and spike-negative data, respectively. Note that there is a large discrepancy between the Dice+ and Dice− indices because the size of the correct response area relative to the input size is significantly different. Regarding the internal data in Table 4, the ROC-AUC for the single-center and multicenter models averaged 0.9728 and 0.9929, respectively. Similarly, for the external data, the ROC-AUC averaged 0.9426. The classification and segmentation performance improved when data from multiple centers were mixed and trained for all centers and indicators except recall in Center D. However, the performance of the external data was inferior to that of the internal data in the tables.

Continuous data evaluation

Automated spike detection was executed on each participant’s resting-state measurement data, and dipole estimation was conducted based on the detection time and sensor. Subsequently, the estimated dipoles were clustered. The accuracy of the automatic analysis was assessed by comparing its results with those obtained through a manual analysis conducted by a neurophysiologist. Table 5 presents the breakdown of the neurophysiologist’s analysis results and the automatic analysis results in the continuous data analysis for the spike-positive data set. The purpose is to demonstrate that the automatic analysis can reproduce the neurophysiologist’s results. To determine a match, we used a previous study41, as a reference and considered clusters with a distance of 15 mm or less between their center coordinates. The table shows the percentage of all clusters and the percentage of clusters that either did not form or did not match, even if they did form. When training with data from all centers, the rate of cluster matches was higher for internal data. However, like the external data, there were instances where spikes were not detected enough to form clusters in some of the data, rendering comparisons impossible for both the neurophysiologist and automated analyses. Additionally, there were cases where clusters did not match. The assessment outcomes are presented in Table 6. In addition, a comparison of the number of spike detections, dipole intensity, GoF, confidence volume (CV), and cluster size is presented in Supplementary Table S3. Similar to the results of the segment data evaluation, the model trained on the multi-center data reproduced the neurophysiologist’s analysis better than the results of the model trained on the single-center data. As for the external data, although the reproducibility was lower than that of the internal data, the results of the dipole analysis were reasonable in light of the criteria from previous literature38 as a measure of dipole. Regarding the internal data in Table 6, the median distance between the neurophysiologist-analyzed dipole and the dipole automatically detected by the single-center and multicenter models was 4.93 and 4.36 mm, respectively. Similar to the segmented data, the model trained on multicenter data reproduced the outcomes of the neurophysiologist better. Regarding the external data shown in Table 6, the median distance between the neurophysiologist-analyzed dipole and the dipole automatically detected by the multicenter models was 7.23 mm. In the external data, although the model did not replicate the neurophysiologist’s results as accurately as with the internal data for the automatically detected spikes, it performed equally well when focusing only on cases in which dipoles clustered. Figure 2 shows three examples comparing the dipole clusters constructed for each of the single-center and multicenter models with those of the neurophysiologist. Although this is an example, it reflects the characteristics of each model.

The processing duration is contingent on the number of spikes detected. To approximate the processing time for each center, a regression equation was used and subsequently averaged. The equation in question possessed an \(R^2\) = 0.86, wherein the processing time \(processing \, time \approx 0.3 \times (\# detected \, spikes) + 56.0\) (in seconds). The intercept of the regression equation was subject to variation based on several factors, including the measurement time, sampling frequency, and sensor quantity.

Examples of dipole clusters from three patients. The dipole clusters, which were analyzed automatically using both the single-center and multi-center models, were compared with those created by the neurophysiologist’s analysis, utilizing the same parameters. Each point represents an estimated dipole, with a 95% confidence ellipsoid constructed around it. The dipole clusters obtained from the neurophysiologist’s analysis are depicted in red; those from the single-center model are illustrated in green; and those from the multi-center model are depicted in blue. The origin in the figure represents the origin of the MEG coordinate system. Also, N represents the number of estimated dipoles in each analysis..

Discussion

As presented in Table 4, amalgamating data from multiple centers ameliorates the model’s performance, unlike training it solely on data from a single center. In deep learning, it is widely acknowledged that performance increases with an increase in data; nonetheless, this presupposes that the labels and data are devoid of noise42. In our study, to further enhance performance, we addressed the issue of limited data available at a single center using data from multiple centers. Considering that the number and arrangement of sensors differed depending on the MEGs in each institution, we standardized and supplemented them to minimize the impact of equipment differences. Additionally, we believe that the environmental magnetic field and participant characteristics of each center also influenced the accuracy, and we contend that the new augmentation technique is a more effective method for training the model. As shown in Table S2 in the Supplementary Content, we achieved further improvement in performance by aggregating data from multiple centers and applying our augmentations. In both classification and segmentation, our approach had a more potent effect on recall and precision than on specificity, signifying that the model responded more accurately to spikes and less accurately to background brain magnetic fields. This has augmented the ability of neurophysiologists to reproduce the results of their analyses. Thus, a single center alone could not sufficiently learn the characteristics of spikes, and learning the various forms of spikes observed at multiple centers amplified the generalization performance for various unknown differences depending on the institution, including environmental noise and the classification criteria of spikes. For the external data, we achieved a performance equivalent to that of the single-center model of the internal data, implying that the model acquired the generic features of the spikes.

Similar to the assessment of the segmented data, the examination of continuous data verified the enhanced performance of the multi-center model. Table 6 suggests that the model trained with multi-center data augmented the reproducibility of the detected spikes, corroborating its ability to detect various types of spikes that could not be acquired with the single-center model. Not only did the model trained on multi-center data increase sensitivity, but it also facilitated the suppression of FPs. Specifically, in the case of Center D, where the number of spike-negative cases was low, the single-center model resulted in numerous false positives; however, learning with multi-center data significantly reduced the number of false positives. Learning with data from multiple centers resulted in superior dipole location accuracy and cluster overlap. In dipole estimation, accurate estimation of the spike onset and peak times is vital, but sensor selection is also crucial. Our findings, as presented in Table 4, suggest that learning with data from multiple centers enabled us to reproduce the neurophysiologist’s sensor selection with higher accuracy, which improved the final dipole estimation outcomes and resulted in better cluster reproducibility. As illustrated in Fig. 2, even when the neurophysiologist’s dipole clusters were small and agglomerated, the single-center model estimated a broad range of dipoles, whereas the multicenter model demonstrated high cohesion of dipoles and high reproducibility of clusters. Although there were some cases in which clusters were not constructed, as shown in Table 5, more cases matched the clusters analyzed in the multicenter model than in the single-center model compared with the neurophysiologist’s clusters. This can be attributed to the detection of spikes that could not be detected in the single-center model and an increase in the number of cases in close proximity to the neurophysiologist’s cluster caused by the improved accuracy of sensor selection. In the external data, the reproducibility of the detected spikes was not as high as that of the internal data. However, the overlap with the clusters analyzed by neurophysiologists was comparable to that of the internal data.

Based on the concept that the automated model should have high specificity rather than high sensitivity, the current model was designed from the perspective of the basic diagnostic principle of epilepsy based on EEG or MEG. Based on this concept, the model was designed to detect only typical spikes with relatively large amplitudes. This contributes to a reduction in false-positive diagnoses of epilepsy, which is vital in clinical practice. However, this method may fail to detect abnormal epileptic waves. Hence, if we use an automated model for screening tests of epilepsy, it would be better to identify not only typical spikes with high specificity but also various epileptogenic waves in addition to typical spikes. Moreover, because the data utilized in this study were evaluated in a clinical context, the number of participants, their ages, and spike criteria varied among the centers. Consequently, there were differences in performance at each site. This suggests that the parameters may require adjustments at each center for practical implementation. Additionally, we posit that collecting a specific amount of data and performing transfer learning43 or domain adaptation44 of the model can lead to a higher level of detection accuracy when working at centers other than the training data collection center. In addition, previous studies have compared manually analyzed dipoles with the resected area of epileptic lesions and reported that the prognosis of resection is better when dipole clusters are constructed within or close to the resected area41,45,46. On the contrary, it has been reported that the percentage of patients who maintained Engel class I at 10 years is approximately 60% for complete resection and approximately 20% for partial resection47. Although our method was able to better reproduce the results of the neurophysiologist’s analysis by learning from multi-center data, a comparison with resection is necessary for a final evaluation.

Conclusion

In this study, we used data obtained from multiple facilities to train a model for the precise identification of epileptic spikes using MEG. Our results confirm the model’s ability to achieve superior accuracy not only for the facilities employed in the training but also for those not included. These findings can significantly reduce the labor-intensive spike detection tasks performed by neurophysiologists.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author(M.H.). The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Code availability

Demonstrations of the model and augmentation are available from CodeOcean (https://codeocean.com/capsule/8268914/tree/v1). Other training and evaluation codes can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author (M.H.).

References

Barkley, G. L. & Baumgartner, C. MEG and EEG in epilepsy. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 20, 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004691-200305000-00002 (2003).

Hämäläinen, M., Hari, R., Ilmoniemi, R. J., Knuutila, J. & Lounasmaa, O. V. Magnetoencephalography-theory, instrumentation, and applications to noninvasive studies of the working human brain. Rev. Mod. Phys. 65, 413–497. https://doi.org/10.1103/revmodphys.65.413 (1993).

Scherg, M. Fundamentals if dipole source potential analysis. In Auditory evoked magnetic fields and electric potentials vol. 6 of Advances in audiology (eds Grandori, F. et al.) 40–69 (Karger, 1990).

Tiège, X. D., Lundqvist, D., Beniczky, S., Seri, S. & Paetau, R. Current clinical magnetoencephalography practice across Europe: Are we closer to use MEG as an established clinical tool?. Seizure 50, 53–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2017.06.002 (2017).

Bagić, A. I., Knowlton, R. C., Rose, D. F., Ebersole, J. S. & Committee, A. C. P. G. C. American clinical magnetoencephalography society clinical practice guideline 1. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 28, 348–354. https://doi.org/10.1097/wnp.0b013e3182272fed (2011).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 60, 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1145/3065386 (2017).

Liu, Z. et al. (2021) Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 9992–10002. https://doi.org/10.1109/iccv48922.2021.00986 (2021).

Howard, J. & Ruder, S. Universal Language Model Fine-tuning for Text Classification. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers) 328–339, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/p18-1031 (2018).

Che, Z., Purushotham, S., Cho, K., Sontag, D. & Liu, Y. Recurrent neural networks for multivariate time series with missing values. Sci. Rep. 8, 6085. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-24271-9 (2018).

Liu, M. et al. SCINet: Time Series Modeling and Forecasting with Sample Convolution and Interaction. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2106.09305 (2021).

Woodland, M. et al. Evaluating the performance of StyleGAN2-ADA on medical images. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2210.03786 (2022).

Zheng, L. et al. EMS-Net: A deep learning method for autodetecting epileptic magnetoencephalography spikes. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 39, 1833–1844. https://doi.org/10.1109/tmi.2019.2958699 (2020).

Jing, J. et al. Development of expert-level automated detection of epileptiform discharges during electroencephalogram interpretation. JAMA Neurol. 77, 103–108. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.3485 (2020).

Aoe, J. et al. Automatic diagnosis of neurological diseases using MEG signals with a deep neural network. Sci. Rep. 9, 5057. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41500-x (2019).

Fukumori, K., Yoshida, N., Sugano, H., Nakajima, M. & Tanaka, T. Epileptic spike detection by recurrent neural networks with self-attention mechanism. In ICASSP 2022–2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) 1406–1410, https://doi.org/10.1109/icassp43922.2022.9747560 (2022).

Cheng, C. et al. Multiview feature fusion representation for interictal epileptiform spikes detection. Int. J. Neural Syst. 32, 2250014. https://doi.org/10.1142/s0129065722500149 (2022).

Hirano, R. et al. Fully-automated spike detection and dipole analysis of epileptic MEG using deep learning. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 41, 2879–2890. https://doi.org/10.1109/tmi.2022.3173743 (2022).

Bento, M., Fantini, I., Park, J., Rittner, L. & Frayne, R. Deep learning in large and multi-site structural brain MR imaging datasets. Front. Neuroinform. 15, 805669. https://doi.org/10.3389/fninf.2021.805669 (2022).

Yu, A. C., Mohajer, B. & Eng, J. External validation of deep learning algorithms for radiologic diagnosis: A systematic review. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 4, e210064. https://doi.org/10.1148/ryai.210064 (2022).

Alvarez-Estevez, D. & Rijsman, R. M. Inter-database validation of a deep learning approach for automatic sleep scoring. PLoS ONE 16, e0256111. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256111 (2021) arXiv:2009.10365.

Parkkonen, L. & Salmelin, R. 65Measurements. In MEG: An Introduction to Methods (eds Hansen, P. et al.) (Oxford University Press, 2010). https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195307238.003.0003.

Sekihara, K. et al. Dual signal subspace projection (DSSP): A novel algorithm for removing large interference in biomagnetic measurements. J. Neural Eng. 13, 036007. https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2560/13/3/036007 (2016).

Shorten, C. & Khoshgoftaar, T. M. A survey on image data augmentation for deep learning. J. Big Data 6, 60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-019-0197-0 (2019).

Téllez-Zenteno, J. F. & Hernández-Ronquillo, L. A review of the epidemiology of temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. Treatm. 2012, 630853. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/630853 (2012).

Yang, Y. & Soatto, S. FDA: Fourier domain adaptation for semantic segmentation. In 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 4084–4094, https://doi.org/10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.00414 (2020).

Zhang, H., Cisse, M., Dauphin, Y. N. & Lopez-Paz, D. mixup: Beyond Empirical Risk Minimization. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1710.09412 (2017).

Taulu, S. & Hari, R. Removal of magnetoencephalographic artifacts with temporal signal-space separation: Demonstration with single-trial auditory-evoked responses. Hum. Brain Mapp. 30, 1524–1534. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20627 (2009).

Babiloni, C. et al. Sources of cortical rhythms in adults during physiological aging: A multicentric EEG study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 27, 162–172. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20175 (2006).

Roy, A. G., Navab, N. & Wachinger, C. Concurrent Spatial and Channel Squeeze & Excitation in Fully Convolutional Networks. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1803.02579 (2018).

Wan, L., Zeiler, M., Zhang, S., Le Cun, Y. & Fergus, R. Regularization of neural networks using dropconnect. In International Conference on Machine Learning,= 1058–1066 (PMLR, 2013).

Yu, F. & Koltun, V. Multi-scale context aggregation by dilated convolutions. arXiv:1511.07122 (2015).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 770–778, https://doi.org/10.1109/cvpr.2016.90 (2016).

Li, R. et al. DeepUNet: A deep fully convolutional network for pixel-level sea-land segmentation. IEEE J. Select. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 11, 3954–3962. https://doi.org/10.1109/jstars.2018.2833382 (2018).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, October 5-9, 2015, Proceedings, Part III 18 234–241 (Springer, 2015).

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1711.05101 (2017).

Drozdzal, M., Vorontsov, E., Chartrand, G., Kadoury, S. & Pal, C. The Importance of Skip Connections in Biomedical Image Segmentation. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1608.04117 (2016).

Nowak, R., Santiuste, M. & Russi, A. Toward a definition of MEG spike: Parametric description of spikes recorded simultaneously by MEG and depth electrodes. Seizure 18, 652–655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2009.07.002 (2009).

Ayako, O., Cristina, Y. G. & Hiroshi, O. Clinical meg analyses for children with intractable epilepsy. In Magnetoencephalography (ed. Pang, E. W.) (IntechOpen, 2011). https://doi.org/10.5772/27256.

Schubert, E., Sander, J., Ester, M., Kriegel, H. P. & Xu, X. DBSCAN revisited, revisited: Why and how you should (Still) use DBSCAN. ACM Trans. Database Syst. 42, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1145/3068335 (2017).

Laohathai, C. et al. Practical fundamentals of clinical MEG interpretation in epilepsy. Front. Neurol. 12, 722986. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.722986 (2021).

Tamilia, E. et al. Assessing the localization accuracy and clinical utility of electric and magnetic source imaging in children with epilepsy. Clin. Neurophysiol. 130, 491–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2019.01.009 (2019).

Schulz, M.-A. et al. Different scaling of linear models and deep learning in UKBiobank brain images versus machine-learning datasets. Nat. Commun. 11, 4238. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18037-z (2020).

Opbroek, Av., Ikram, M. A., Vernooij, M. W. & Bruijne, Md. Transfer learning improves supervised image segmentation across imaging protocols. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 34, 1018–1030. https://doi.org/10.1109/tmi.2014.2366792 (2015).

Guan, H., Liu, M. & Liu, M. Domain adaptation for medical image analysis: A survey. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 69, 1173–1185. https://doi.org/10.1109/tbme.2021.3117407 (2021) arXiv:2102.09508.

Lau, M., Yam, D. & Burneo, J. A systematic review on meg and its use in the presurgical evaluation of localization-related epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 79, 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2008.01.004 (2008).

Ntolkeras, G. et al. Presurgical accuracy of dipole clustering in MRI-negative pediatric patients with epilepsy: Validation against intracranial EEG and resection. Clin. Neurophysiol. [SPACE] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2021.01.036 (2021).

Rampp, S. et al. Magnetoencephalography for epileptic focus localization in a series of 1000 cases. Brain 142, 3059–3071. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awz231 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding

This study was supported by the collaborative grants from the RICOH Corporation. Each center was funded by RICOH in exchange for working on data collection and sorting. The sponsors provided no instructions regarding study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, report writing, and decision to submit a paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.H. wrote the manuscript. R.H. and M.A. analyzed the data. R.H. and M.H. designed and conceptualized the study. M.H. reviewed the manuscript. M.H., N.N., A.K., T.U., N.T., M.Y., Y.S. and T.O. collected the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study complied with applicable ethical guidelines, including ethical approval, Declaration of Helsinki compliance, and institutional ethical guidelines. The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of Osaka University Hospital (No. 19484-5), Ethical Committee of Osaka Metropolitan University Graduate School of Medicine (No. 2020-033), Ethics Committee Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine (No. 2020-1-1065), Ethics Committee of National Epilepsy Center, NHO Shizuoka Institute of Epilepsy and Neurological Disorders (No.2020-01), Ethics Committee of Kumagaya General Hospital (No. 2020-41), and Ethics Committee of Hokuto Hospital (No. 1077).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hirano, R., Asai, M., Nakasato, N. et al. Deep learning based automatic detection and dipole estimation of epileptic discharges in MEG: a multi-center study. Sci Rep 14, 24574 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75370-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75370-9