Abstract

The rupture of vulnerable plaque (VP) are significant pathogenic factors leading to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. This study aims to construct a vulnerable plaque prediction model (VPPM) by combining multimodal vascular ultrasound parameters and clinical risk factors, and to validate it. A total of 196 atherosclerotic patients who underwent carotid endarterectomy (CEA) from January 2017 to December 2023 were collected and divided into a modeling group (n = 137) and a validation group (n = 59). Clinical information including: hypertension, diabetes, smoking history, and body mass index (BMI) was included in the analysis. All patients underwent carotid ultrasound and contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) examination after admission, with main ultrasound parameters including thickness, echogenicity types, stenosis degree, and CEUS neovascularization grading of plaques. Independent risk factors for VP in CEA patients were screened through binary Logistic regression analysis, and a prediction model was established along with a nomogram. The calibration curve, receiver-operating characteristic curve (ROC), and decision curve analysis (DCA) were employed to assess the calibration, diagnostic efficacy, and clinical utility of the VPPM model. There were no significant statistical differences in multimodal vascular ultrasound parameters and clinical risk factors between the modeling and validation groups (P > 0.05). Binary Logistic regression analysis identified plaque thickness, echo type, CEUS neovascularization grading, BMI, and smoking history as 5 variables entering the prediction model. The VPPM model showed good diagnostic efficacy, with an area under the ROC curve of 0.959 (95% CI 0.915–0.999). Using the nomogram with a VPPM risk assessment score of 135.42 as the diagnostic cutoff value in the modeling group, the sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio, negative likelihood ratio, and Youden index were 88.1%, 94.1%, 14.98, 0.126, and 82.2%, respectively. In the DCA curve, the VPPM model curve was significantly better than two extreme lines, indicating good clinical utility. The VPPM model constructed by integrating multimodal ultrasound parameters and clinical key risk factors has high diagnostic efficacy and is expected to be an auxiliary tool for clinical diagnosis of vulnerable plaques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vulnerable plaque is a crucial factor contributing to cardiovascular events induced by atherosclerosis (AS)1,2,3. Carotid endarterectomy (CEA) is the primary surgical approach for treating carotid AS4,5, with plaque pathology serving as the gold standard for diagnosing vulnerable plaques. The main pathological features include a thin fibrous cap, a large lipid-rich necrotic core, abundant inflammatory cells, few smooth muscle cells, abundant neovascularization, and intra-plaque hemorrhage6,7.

Vulnerable plaques exhibit complex compositional and histological characteristics. Previous studies have extensively assessed plaques through imaging techniques such as ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Two-dimensional ultrasound primarily estimates the nature of plaques based on their echo and morphology, but traditional ultrasound alone cannot meet clinical demands. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) can dynamically detect neovascularization within plaques8, which plays a crucial role in plaque vulnerability by being a major source of intra-plaque hemorrhage9,10,11.

Prior researches12,13,14,15,16,17 have indicated that numerous clinical risk factors are associated with AS and plaque vulnerability. Aging is an independent risk factor for AS, as elderly individuals often have other cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes, and aging itself can cause changes in vascular wall structure and function12,13. Diabetes, characterized by high blood sugar and insulin resistance, along with factors such as increased glycation end products, inflammation, oxidative stress, and lipid metabolism disorders, is a significant risk factor for AS formation14. Bouwhuijsen et al. found hypertension and smoking to be risk factors for intra-plaque hemorrhage by examining carotid plaque characteristics using MRI15. Smoking is a crucial risk factor for disability and death from cerebrovascular diseases16. Ohashi et al. found that obesity, particularly increased visceral fat content, independently predicts the presence of non-calcified coronary artery plaques, which often exhibit vulnerable characteristics17.

Therefore, using histopathology as the gold standard for vulnerable plaques, the study aims to combine multimodal vascular ultrasound parameters with key clinical risk factors to construct a vulnerable plaque prediction model (VPPM) and validate the model’s value in diagnosing vulnerable plaques.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

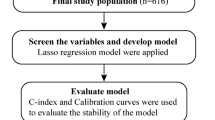

Patients admitted to vascular surgery department who underwent carotid endarterectomy (CEA) surgery from January 2017 to December 2023 were included in the study. Patients were divided into a modeling group containing 2/3 of the patients and a validation group containing the remaining 1/3 of the patients according to their admission times. The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University (Approval No: MRCTA, ECFAH of FMU [2021]428). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The inclusion criteria for CEA patients were as follows18: (1) patients with severe carotid artery stenosis (70-99%) without recent significant cerebral ischemic symptoms; (2) patients with mild or moderate ipsilateral carotid artery stenosis, who still experienced transient ischemic attacks or ischemic strokes recently. All enrolled subjects underwent preoperative carotid ultrasound and CEUS examinations. Exclusion criteria were: (1) patients with severe multi-organ dysfunction; (2) patients with carotid artery stenosis due to other causes, such as large-vessel vasculitis and arterial dissection; (3) patients with calcified plaques making it difficult for ultrasound to penetrate; (4) patients allergic to ultrasound contrast agent (SonoVue) (see Fig. 1).

Clinical data including gender, age, body mass index (BMI), smoking history, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, history of statin use, and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were collected from patients’ medical records.

Ultrasound examination

Carotid artery ultrasound and CEUS examination

Carotid artery ultrasound and CEUS examinations were performed by an ultrasound physician with over 10 years of vascular ultrasound experience, using a Philips EPIC-Q7 (USA) ultrasound diagnostic instrument equipped with a vascular linear array transducer (frequency 3-12 MHz). The mechanical index, image depth, and focus position were adjusted to 0.2–0.3, 4–5 cm, and 3–4 cm, respectively. Target plaques were continuously scanned in longitudinal and transverse sections, and the maximum thickness of the plaque was measured. The echo type, surface morphology, and distribution of calcification of each plaque were carefully observed. According to the American College of Radiology ultrasound consensus19, a comprehensive grading of luminal stenosis was performed using two-dimensional and Doppler ultrasound (see Fig. 2).

Scans from a 72-year-old man with right carotid atherosclerotic plaque. (a, b) CDFI showed the color mosaic blood flow in lumen stenosis caused by the responsible plaque and PSV was 645 cm/s. (c) Extensive intraplaque enhancement were visible on CEUS (grade 2). (d) Histologic section from the CEA specimen with HE stains (magnification, 40): intra-plaque hemorrhage can be seen (white arrow). CEUS contrast-enhanced ultrasound, CDFI color Doppler flow imaging, CEA carotid endarterectomy; HE hematoxylin–eosin, PSV peak systolic velocity.

A total of 1.5-2 ml of contrast agent (SonoVue [Bracco Imaging, Milan, Italy]) was injected into the median cubital vein, followed by flushing with 5 ml of normal saline. The frame rate was set at 10–15 fps, mechanical index at 0.1, and dynamic range at 50–60 dB. The upper shoulder, middle part, and lower shoulder of the target plaque were observed for the entry of contrast microbubbles from the intima or adventitia. Dynamic videos were observed and recorded for at least 60 s after injection. Contrast microbubbles typically appeared within 10–20 s after injection. Additionally, all static images and dynamic real-time videos of CEUS were saved for offline analysis. It is important to distinguish contrast microbubbles from artifacts. (see Fig. 2)

Image analysis

Two experienced ultrasound physicians evaluated and graded the two-dimensional and CEUS images of the plaques: (1) plaque thickness: ≤2 mm was grade 0, > 2–3 mm was grade 1, 3–4 mm was grade 2, and ≥ 4 mm was grade 3; (2) plaque morphology: regular morphology plaque was grade 0, irregular morphology plaque was grade 1; (3) plaque echo type: homogeneous isoechoic plaque was grade 0, homogeneous hypoechoic plaque was grade 1, heterogeneous plaque with < 50% low or no echo area was grade 2, heterogeneous plaque with > 50% low or no echo area was grade 3; (4) plaque calcification: no calcification was grade 0, speckled calcification at the base was grade 1, speckled calcification at the top was grade 2; (5) extremely low echo area within the plaque: absent was grade 0, present was grade 1; (6) degree of stenosis: <50% was grade 0, 50–69% was grade 1, 70–99% was grade 2; (7) CEUS plaque neovascularization: no bubbles within the plaque or bubbles limited to the plaque’s outer wall was grade 0, moderate enhancement with moving microbubbles within the plaque was grade 1, widespread enhancement within the plaque with obvious microbubble entry into the plaque core was grade 220.

Histopathological examination

All CEA plaque specimens were fixed, decalcified, and paraffin-embedded in 10% formalin buffer. Sections with a thickness of 3 mm were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and observed to differentiate vulnerable plaques from non-vulnerable plaques based on histological morphology and composition.

The consensus literature has proposed the diagnostic criteria of histopathological features for vulnerable plaques21: a core of lipid necrosis(area ratio>40%), intraplaque neovascularization, intraplaque hemorrhage, thin/ruptured fibrous cap(<65 μm), and active inflammation(massive infiltration of macrophages and lymphocytes).

Statistical analysis

SPSS 25.0 software and R language (version 4.3.2) were used for data analysis. Normally distributed continuous data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (\(\:\stackrel{-}{x}\)±s), while non-normally distributed data were expressed as median M (P25-P75). Independent sample t-test was used to compare the means between two groups with normally distributed data, and Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-normally distributed data comparison. Count data were expressed as n (%) and compared using the chi-square test. Variables related to plaque vulnerability (P < 0.1) were subjected to binary logistic regression analysis to select independent influencing variables (P < 0.05) for inclusion in the final prediction model construction. The nomogram function in the rms package of R language was used to plot the nomogram of the VPPM model. Bootstrap method was used for internal validation of the nomogram prediction model by repeating sampling 1000 times. ROC curve was plotted using SPSS software and the cutoff value was calculated, and the area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC) within a 95% confidence interval was used to evaluate the predictive ability of the model. The calibration plot was drawn using the val.prob function in the rms package of R language, and the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was used to test the consistency between the modeling group and the validation group. The DCA curve was plotted using the dca package in R language to determine the clinical utility of the nomogram. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Comparison of demographic characteristics, ultrasound parameters, and clinical risk factors between the modeling group and validation group

A total of 196 consecutive CEA patients were included in this study, who were divided into modeling group (n = 137) and validation group (n = 59) in chronological order. There were no significant statistical differences in demographic characteristics, ultrasound parameters, and clinical risk factors between the modeling group and validation group (P > 0.05) (Table 1), indicating good consistency between the two groups.

Univariate analysis of variables in the modeling group

According to the pathological results, patients in the modeling group were divided into the non-vulnerable plaque group (n = 48) and vulnerable plaque group (n = 89). Except for gender, age, and plaque morphology, which showed no significant differences between the two groups (P > 0.05), the remaining indicators showed significant differences between the two groups (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Multivariate analysis of vascular ultrasound parameters and clinical risk factors in the modeling group

Variables with statistical differences in univariate analysis (see Table 2) were included in binary logistic regression analysis. The results showed that thickness, echo, CEUS, smoking, and BMI were independent risk factors for vulnerable plaques (see Table 3), with OR values of 3.084 (95%CI: 2.018–3.169), 5.059 (95%CI: 4.026–6.182), 3.039 (95%CI: 2.205–4.310), 3.286 (95%CI: 2.106–4.335), and 1.689 (95%CI: 1.011–1.942), respectively.

Construction and nomogram plot of the VPPM model

Based on the results of multivariate analysis, five variables including thickness, echo, CEUS, smoking, and BMI were finally included in the prediction model, and a nomogram plot was drawn as shown in Fig. 3. According to the contribution degree of the five influencing factors in the model to the outcome variable (the size of the regression coefficient), assign scores to each value level of each influencing factor, add up the scores to obtain the total score, and finally obtain the probability of vulnerable plaques through the total score. The Bootstrap method was used to internally validate the nomogram prediction model by repeated sampling 1000 times.

VPPM prediction model. For example, a patient with a plaque thickness > 3 mm scored 43 points, heterogeneous hypoechogenicity scored 72 points, CEUS neovascularization grade 2 scored 29 points, smoking history scored 31 points, BMI = 30 scored 78 points, and the final score for the patient was 253 points. At this point, the probability of being diagnosed as a vulnerable plaque according to the VPPM model was about 99.9%, and the pathological results of this patient also confirmed that it was a vulnerable plaque.

Calibration curves of the modeling group and validation group

The predicted curves of the modeling group and validation group were distributed along the 45° line (standard line), indicating good accuracy of the VPPM. The calibration curve showed good consistency between the predicted and observed data in the modeling group and validation group (Fig. 4), suggesting that the model fits well with the observed data and is suitable for predicting vulnerable plaques.

Calibration curves for predicting vulnerable plaques in the modeling group (a) and validation group (b). The calibration curve (solid line) is close to the ideal reference line (dashed line), indicating that the predicted results are consistent with the actual results, demonstrating good performance of the nomogram in both the modeling and validation groups.

ROC curves of variables in the modeling group and validation group

ROC curves were used to evaluate the predictive accuracy of each variable in the model. As shown in Fig. 5, the VPPM model had the best diagnostic performance, with an AUC value of 0.959 (95% CI: 0.915–0.999) in the modeling group, which was higher than that of other variables (see Table 4). When the risk assessment value of the nomogram VPPM was 135.42, the sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio, negative likelihood ratio, and Youden index of the model were 88.1%, 94.1%, 14.98, 0.126, and 82.2%, respectively.

DCA curves of the modeling group and validation group

The DCA curves of the VPPM and other variables’ clinical decision-making are shown in Fig. 6. The VPPM curve is located at the upper right corner of the graph, indicating better clinical decision-making performance.

DCA curves for predictive models in the modeling group (a) and validation group (b). In the DCA curves, the model curve in the modeling group is significantly better than the two extreme lines, indicating good overall population benefit; and similarly, it performs excellently in the validation group.

Discussion

Atherosclerosis leading to cerebrovascular diseases is a significant contributor to the increasing global mortality and disability rates22, with vulnerable plaques being the main culprit behind cerebrovascular thromboembolic events23,24. In recent years, researchers have been devoted to using various imaging techniques to diagnose vulnerable plaques and identify related clinical risk factors contributing to their formation.

This study combined multi-modal vascular ultrasound parameters and key clinical risk factors to construct the VPPM model and validated it. The results revealed that plaque thickness, echo type, CEUS neovascularization grading, BMI, and smoking history were independent risk factors for vulnerable plaques. ROC curves demonstrated good diagnostic performance of the VPPM model in both the modeling and validation groups. In the DCA curves, the model curves in both groups were significantly better than the two extreme lines, indicating good clinical applicability of the model.

Relationship between AS clinical risk factors and plaque vulnerability

Studies have shown that cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and increased BMI are associated with increased intima-media thickness of the carotid artery and promote plaque formation25. High cholesterol levels and smoking are closely related to the increased risk of carotid artery stenosis26, and the incidence of AS in diabetic patients is higher27. The results of this study showed that in the vulnerable plaque group, there were statistically significant differences compared to the non-vulnerable plaque group in terms of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, BMI, CRP, hyperlipidemia, and smoking history (P < 0.05). Logistic regression analysis further identified BMI and smoking history as independent predictors of vulnerable plaques. Previous studies have found that patients with a BMI > 25 kg/m2 have a high risk of developing high-risk characteristic plaques, and BMI is an independent predictor of future acute coronary events28. The mechanism may involve excessive adipose tissue causing lipid metabolism disorders, insulin resistance, aggravation of endothelial dysfunction, increased reactive oxygen species, decreased nitric oxide utilization, enhanced inflammatory response, and increased secretion of pro-inflammatory factors29,30,31. Kumagai et al.32 investigated the effect of smoking on coronary artery plaques using intravascular ultrasound and found that smoking was independently associated with lipid-rich plaques, contributing to increased plaque vulnerability. Smoking may promote plaque rupture by inducing the expression of inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6 in the circulation, and inducing increased expression of matrix metalloproteinases in the plaque33,34.

Relationship between multi-modal ultrasound parameters and plaque vulnerability

Nyman et al.35 found that ultrasound has high repeatability in detecting plaques and is a reliable detection method. Conventional two-dimensional ultrasound can visually observe plaque thickness, morphology, echo type, and degree of stenosis. This study included plaque thickness, echo type, morphology, and degree of vascular stenosis as the main parameters of plaque ultrasound features, all of which showed significant statistical differences between the vulnerable plaque group and the non-vulnerable plaque group (P < 0.05). However, binary logistic regression analysis found that only plaque thickness, echo, and CEUS neovascularization grading were independent risk factors for vulnerable plaques. Previous studies have found that plaque echo intensity is correlated with plaque tissue composition, where extremely low echo areas within the plaque represent lipid cores or intraplaque hemorrhage, while strong or high echo areas represent calcification and fibrosis of the plaque, with increased calcification and fibrosis indicating increased plaque stability36. Spanos et al.37 found that patients with lower preoperative plaque echo intensity had higher levels of macrophage infiltration and larger lipid volumes within the plaque, as well as a higher incidence of plaque rupture. A higher proportion of extremely low echo areas38 or echo-free areas39 within the plaque indicates potential unstable lesions, which are also related to neurological symptoms. Gupta et al.40,41 found that in patients with carotid artery stenosis of 50–99%, the probability of stroke in patients with low echo plaques was 2.6 times higher than that in patients with strong echo plaques. Therefore, in this study, the proportion of low or echo-free areas within the plaque was used to grade plaque echo, with the highest grade assigned to heterogeneous echo types with a proportion of low or echo-free areas > 50%.

Conventional two-dimensional ultrasound combined with color Doppler flow imaging has been widely used for measuring the degree of carotid artery atherosclerotic plaque stenosis and evaluating plaque composition42. However, conventional two-dimensional ultrasound cannot detect neovascularization within the plaque, and its inter-operator consistency is low, which is a major limitation in evaluating plaque vulnerability using two-dimensional ultrasound. CEUS is recognized as a tool for real-time detection of neovascularization43, with minimal invasiveness and unique advantages44,45, and has gradually been used as one of the standards for diagnosing vulnerable plaques. Studies have shown that CEUS can semi-quantitatively assess neovascularization based on the degree of enhancement of contrast agents. Weak endothelium of neo vessels within the plaque makes them prone to rupture, leading to intraplaque hemorrhage, accompanied by the release of chemical mediators into the plaque, increased inflammation46,47, and increased vulnerability of the plaque, thus increasing the risk of ischemic stroke48. Analysis of large atherosclerotic plaque biobanks has also shown that neovascular density within the plaque is highly correlated with the risk of stroke49. The results of this study showed that CEUS grading of neovascularization within the plaque was an independent influencing factor for vulnerable plaques, further confirming the importance of neovascularization within the plaque in influencing plaque vulnerability.

Construction of a predictive model for vulnerable plaques using multi-modal vascular ultrasound parameters and clinical risk factors

Although there have been many studies on ultrasound assessment of vulnerable plaques and clinical risk factors for AS, there are few reports on the joint construction of predictive models using multi-modal ultrasound parameters and clinical key risk factors. In this study, binary logistic regression was used to analyze multi-modal ultrasound parameters and clinical risk factors, and the results showed that plaque thickness, echo type, CEUS neovascularization within the plaque, smoking history, and BMI were independent risk factors for vulnerable plaques. This study not only constructed a predictive model for vulnerable plaques but also validated the model. ROC curve analysis in the modeling group showed that the AUC value of the VPPM model for predicting vulnerable plaques was 0.959, higher than that of other variables. When the risk assessment value of the nomogram VPPM was 135.42, the model demonstrated sufficient diagnostic performance with sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio, negative likelihood ratio, and Youden index of 88.1%, 94.1%, 14.98, 0.126, and 82.2%, respectively. The calibration curves showed good consistency in the modeling and validation groups, indicating good discrimination and calibration capabilities of the model. In the DCA curves, the model curves in both groups were significantly better than the two extreme lines, indicating good clinical applicability of the model, allowing clinicians to intuitively, accurately, and quantitatively assess plaque vulnerability, thus enabling the development of personalized treatment plans to improve patient prognosis.

Limitations of this study

Firstly, this was a single-center study, although we have validated the model in an independent cohort within the same center, future research need more cases and multicenter external validation studies. Secondly, because the study included few experimental indicators related to vulnerability, future studies could include additional indicators such as matrix metalloproteinase-7 and interleukin-17. Thirdly, the sample size of this study was small, and due to the need to obtain pathological gold standards, all enrolled subjects were CEA patients, which may have caused selection bias.

In summary, the VPPM predictive model constructed based on multi-modal ultrasound parameters and clinical risk factors has good calibration and clinical effectiveness, making it a potentially useful clinical model for diagnosing vulnerable plaques. Future research should focus on identifying new, potential, and valuable risk variables associated with plaque vulnerability for testing and validation in future clinical prediction models.

Data availability

Requests for access to the dataset should be directed to the first author: Lei Yan, yanlei20082336@163.com.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CEUS:

-

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound

- CDFI:

-

Color Doppler flow imaging

- CEA:

-

Carotid endarterectomy

- HE:

-

Hematoxylin–eosin

- PSV:

-

Peak systolic velocity

- MR:

-

Magnetic resonance

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- VP:

-

Vulnerable plaque

- VPPM:

-

Vulnerable plaque prediction model

- 2D:

-

Two-dimensional ultrasound

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- TIA:

-

Transient ischemic attack

References

Bentzon, J. F., Otsuka, F., Virmani, R. & Falk, E. Mechanisms of plaque formation and rupture. Circ. Res. 114(12), 1852–1866. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302721 (2014).

Saba, L. et al. Imaging biomarkers of vulnerable carotid plaques for stroke risk prediction and their potential clinical implications. Lancet Neurol. 18(6), 559–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30035-3 (2019).

Baradaran, H. et al. Carotid artery plaque characteristics: current reporting practices on CT angiography. Neuroradiology 63(7), 1013–1018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-020-02610-w (2021).

Heck, D. & Jost, A. Carotid stenosis, stroke, and carotid artery revascularization. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 65, 49–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2021.03.005 (2021).

Bonati, L. H., Jansen, O., de Borst, G. J. & Brown, M. M. Management of atherosclerotic extracranial carotid artery stenosis. Lancet Neurol. 21(3), 273–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00359-8 (2022).

Libby, P. Mechanisms of acute coronary syndromes and their implications for therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 368(21), 2004–2013. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1216063 (2013).

Puig, N., Jiménez-Xarrié, E., Camps-Renom, P. & Benitez, S. Search for reliable circulating biomarkers to predict carotid plaque vulnerability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(21), 8236. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21218236 (2020).

Magnoni, M., Ammirati, E., Moroni, F., Norata, G. D. & Camici, P. G. Impact of cardiovascular risk factors and pharmacologic treatments on carotid intraplaque neovascularization detected by contrast-enhanced ultrasound. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 32(1), 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2018.09.001 (2019).

Moreno, P. R., Purushothaman, K. R., Zias, E., Sanz, J. & Fuster, V. Neovascularization in human atherosclerosis. Curr. Mol. Med. 6(5), 457–477. https://doi.org/10.2174/156652406778018635 (2006).

van den Oord, S. C. et al. Assessment of carotid atherosclerosis, intraplaque neovascularization, and plaque ulceration using quantitative contrast-enhanced ultrasound in asymptomatic patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 15(11), 1213–1218. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jeu127 (2014).

Goudot, G. et al. Carotid plaque vulnerability assessed by combined shear wave elastography and ultrafast doppler compared to histology. Transl. Stroke Res. 13(1), 100–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-021-00920-6 (2022).

Wang, J. C. & Bennett, M. Aging and atherosclerosis: mechanisms, functional consequences, and potential therapeutics for cellular senescence. Circ. Res. 111(2), 245–259. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.261388 (2012).

Ruiz-García, J. et al. Age- and gender-related changes in plaque composition in patients with acute coronary syndrome: the PROSPECT study. EuroIntervention 8(8), 929–938. https://doi.org/10.4244/EIJV8I8A142 (2012).

La Sala, L., Prattichizzo, F. & Ceriello, A. The link between diabetes and atherosclerosis. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 26(2_suppl), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487319878373 (2019).

van den Bouwhuijsen, Q. J. et al. Determinants of magnetic resonance imaging detected carotid plaque components: the Rotterdam Study. Eur. Heart J. 33(2), 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehr227 (2012).

Tsao CW, et al. American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2023 Update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023;147(8): e93-e621. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001123.

Ohashi, N. et al. Association between visceral adipose tissue area and coronary plaque morphology assessed by CT angiography. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 3(9), 908–917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.06.014 (2010).

Liapis, C. D. et al. Invasive treatment for carotid stenosis: indications, techniques. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 37(4 Suppl), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.11.006 (2009).

Grant, E. G. et al. Carotid artery stenosis: gray-scale and Doppler US diagnosis–Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference. Radiology 229(2), 340–346. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2292030516 (2003).

Coli, S. et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging of intraplaque neovascularization in carotid arteries: correlation with histology and plaque echogenicity. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 52(3), 223–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2008.02.082 (2008).

Naghavi, M. et al. From vulnerable plaque to vulnerable patient: a call for new definitions and risk assessment strategies: Part I. Circulation 108(14), 1664–1672. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000087480.94275.97 (2003).

Arbab-Zadeh, A. & Fuster, V. From detecting the vulnerable plaque to managing the vulnerable patient: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 74(12), 1582–1593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.07.062 (2019).

Serfaty, J. M. et al. Plaque density on CT, a potential marker of ischemic stroke. Neurology 66(1), 118–120. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000191391.71614.51 (2006).

Gao, T., Zhang, Z., Yu, W., Zhang, Z. & Wang, Y. Atherosclerotic carotid vulnerable plaque and subsequent stroke: a high-resolution MRI study. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 27(4), 345–352. https://doi.org/10.1159/000202011 (2009).

Xu, X., Hua, Y., Wang, L., Hou, W. & Xia, M. Correlation between risk factors of cerebrovascular disease and calcified plaque characteristics in patients with atherosclerotic severe carotid stenosis. Neurol. Res. 42(1), 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616412.2019.1710403 (2020).

Meng, R., Mi, X. & Sun, D. Risk factors for recurrent carotid-artery stenosis following stenting treatment. Med. Sci. Monit. 25, 2429–2434. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.913894 (2019).

Poznyak, A. et al. The diabetes mellitus-atherosclerosis connection: the role of lipid and glucose metabolism and chronic inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(5), 1835. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21051835 (2020).

Motoyama, S. et al. Plaque characterization by coronary computed tomography angiography and the likelihood of acute coronary events in mid-term follow-up. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 66(4), 337–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.069 (2015).

Liu, L. et al. Adipokines, adiposity, and atherosclerosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 79(5), 272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-022-04286-2 (2022).

Ratushnyy, A., Lobanova, M. & Buravkova, L. B. Expansion of adipose tissue-derived stromal cells at “physiologic” hypoxia attenuates replicative senescence. Cell Biochem. Funct. 35(4), 232–243. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbf.3267 (2017).

Yuan, T. et al. New insights into oxidative stress and inflammation during diabetes mellitus-accelerated atherosclerosis. Redox Biol. 20, 247–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2018.09.025 (2019).

Kumagai, S. et al. Impact of cigarette smoking on coronary plaque composition. Coron. Artery Dis. 26(1), 60–65. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCA.0000000000000168 (2015).

Batatinha, H. A. P., Rosa Neto, J. C. & Krüger, K. Inflammatory features of obesity and smoke exposure and the immunologic effects of exercise. Exerc. Immunol. Rev. 25, 96–111 (2019).

Stolle, K., Berges, A., Lietz, M., Lebrun, S. & Wallerath, T. Cigarette smoke enhances abdominal aortic aneurysm formation in angiotensin II-treated apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Toxicol. Lett. 199(3), 403–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.10.005 (2010).

Nyman, E., Vanoli, D., Näslund, U. & Grönlund, C. Inter-sonographer reproducibility of carotid ultrasound plaque detection using Mannheim consensus in subclinical atherosclerosis. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 40(1), 46–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpf.12602 (2020).

Barrett, H. E., Van der Heiden, K., Farrell, E., Gijsen, F. J. H. & Akyildiz, A. C. Calcifications in atherosclerotic plaques and impact on plaque biomechanics. J. Biomech. 87, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2019.03.005 (2019).

Spanos, K., Tzorbatzoglou, I., Lazari, P., Maras, D. & Giannoukas, A. D. Carotid artery plaque echomorphology and its association with histopathologic characteristics. J. Vasc. Surg. 68(6), 1772–1780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2018.01.068 (2018).

Griffin, M. B. et al. Juxtaluminal hypoechoic area in ultrasonic images of carotid plaques and hemispheric symptoms. J. Vasc. Surg. 52(1), 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2010.02.265 (2010).

Hashimoto, H., Tagaya, M., Niki, H. & Etani, H. Computer-assisted analysis of heterogeneity on B-mode imaging predicts instability of asymptomatic carotid plaque. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 28(4), 357–364. https://doi.org/10.1159/000229554 (2009).

Gupta, A. et al. Plaque echolucency and stroke risk in asymptomatic carotid stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 46(1), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006091 (2015).

Sztajzel, R., Momjian-Mayor, I., Comelli, M. & Momjian, S. Correlation of cerebrovascular symptoms and microembolic signals with the stratified gray-scale median analysis and color mapping of the carotid plaque. Stroke 37(3), 824–829. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000204277.86466.f0 (2006).

Murray, C. S. G., Nahar, T., Kalashyan, H., Becher, H. & Nanda, N. C. Ultrasound assessment of carotid arteries: Current concepts, methodologies, diagnostic criteria, and technological advancements. Echocardiography 35(12), 2079–2091. https://doi.org/10.1111/echo.14197 (2018).

Saito, K. et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound for the evaluation of neovascularization in atherosclerotic carotid artery plaques. Stroke 45(10), 3073–3075. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006483 (2014).

Hoogi, A. et al. Carotid plaque vulnerability: quantification of neovascularization on contrast-enhanced ultrasound with histopathologic correlation. Am. J. Roentgenol. 196(2), 431–436. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.10.4522 (2011).

Li, C. et al. Quantification of carotid plaque neovascularization using contrast-enhanced ultrasound with histopathologic validation. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 40(8), 1827–1833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.02.010 (2014).

Jeziorska, M. & Woolley, D. E. Local neovascularization and cellular composition within vulnerable regions of atherosclerotic plaques of human carotid arteries. J. Pathol. 188(2), 189–196 (1999).

Saha, S. A., Gourineni, V. & Feinstein, S. B. The use of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography for imaging of carotid atherosclerotic plaques: Current evidence, future directions. Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am. 26(1), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nic.2015.09.007 (2016).

Cui, L. et al. Carotid intraplaque neovascularisation as a predictive factor for future vascular events in patients with mild and moderate carotid stenosis: an observational prospective study. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 14, 17562864211023992. https://doi.org/10.1177/17562864211023992 (2021).

Howard, D. P. et al. Symptomatic carotid atherosclerotic disease: correlations between plaque composition and ipsilateral stroke risk. Stroke 46(1), 182–189. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007221 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank department of Pathology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical College, for providing pathological images and consultation.

Funding

1. Leading Project Foundation of Science and Technology, Fujian Province (No.2022Y0010); 2. Fujian Provincial Health Technology Project (No. 2020GGB032).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was in accordance with the Ethical Standards of the Institutional Ethics Committee of First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable Ethical Standards. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations in the declaration. Written informed consent was provide by all included patients. Ethics batch number: MRCTA, ECFAH of FMU [2021]428.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, L., Ye, X., Fu, L. et al. Construction of vulnerable plaque prediction model based on multimodal vascular ultrasound parameters and clinical risk factors. Sci Rep 14, 24255 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75375-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75375-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Echogenicity of carotid plaques as a predictor of regression following lipid-lowering therapy

Thrombosis Journal (2025)