Abstract

Optimization algorithms are essential tools used to address real-world problems through minimization or maximization processes. In the context of photovoltaic (PV) systems, various optimization algorithms have been employed to extract solar cell parameters using minimization techniques, and to identify the maximum power point (MPP) using maximization approaches. However, under partial shading conditions or during rapidly changing irradiance, many of these algorithms tend to get trapped in local minima, failing to locate the global maximum power point (GMPPT). This shortcoming leads to significant energy losses from PV cells. Similarly, the extraction of solar cell parameters is often compromised by the random search behavior and inadequate exploration and exploitation capabilities of many existing algorithms. The Jellyfish Search Optimization (JSO) algorithm is a recent, parameter-free method developed to tackle a wide range of optimization problems. Despite its innovative design, JSO is prone to premature convergence and exhibits a longer convergence time. To address these limitations, this paper proposes a modified version of the JSO algorithm, which integrates the state-of-the-art features of JSO with the Lévy flight characteristic from the cuckoo search algorithm. This combination aims to achieve a better balance between exploration and exploitation. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed Improved Jellyfish Search Optimization (IJSO) algorithm in PV systems, extensive experiments were conducted. These experiments included benchmarking with complex test functions, extracting cell parameters using various solar cell models, and maximizing energy output from PV systems under different environmental conditions. The results demonstrate that the proposed IJSO algorithm effectively enhances parameter extraction and global maximum power point tracking, making it a promising solution for optimizing energy extraction from PV cells in dynamic conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The integration of machine learning techniques into real-world problem-solving has evolved significantly in the 21st century due to their robustness compared to traditional numerical algorithms like Newton’s method, gradient descent, linear programming (simplex method), Lagrange multipliers, genetic algorithms, and simulated annealing. While these native methods employ mathematical and analytical techniques to minimize or maximize an objective function under constraints, they are typically suited for solving well-defined, lower-complexity problems1,2,3. In contrast, machine learning techniques have been applied across diverse fields, including aeronautics, the military, medicine, engineering, business administration, law, and education, to address complex computational challenges4,5,6. For example, in the medical sector, support vector machines (SVM), a supervised machine learning technique, are utilized by oncologists to detect early-stage cancer7,8,9. Optimization algorithms, commonly used in machine learning, employ iterative methods to find the input values or objectives that result in the minimum or maximum output of a function. These algorithms are generally classified into two categories: **approximate methods**, which find near-optimal solutions using random approaches, and **exact methods**. Figure 1 presents a flowchart illustrating the branches of optimization techniques and examples of each.

Optimization techniques have been applied in various domains, such as medical science, financial markets, industrial production, data clustering, and military operations10. In renewable energy, researchers have developed several optimization algorithms to extract input parameters that optimize power flow in photovoltaic (PV) systems. These PV models are often represented using a 1-diode model with five parameters or a 2-diode model with seven parameters9,11,12. One prominent application in PV systems is “global maximum power point tracking (GMPPT)”, which involves optimizing power output by adjusting the duty cycle to ensure maximum power generation under varying atmospheric conditions13,14. PV systems are eco-friendly, cost-effective, and have a lifespan of up to 35 years, making them an attractive renewable energy source15,16.

Despite these benefits, PV systems face challenges, particularly during **partial shading conditions**, where uneven light distribution across the panel results in reduced energy generation17,18. Researchers have proposed various methods to address this issue, including advanced GMPPT techniques that precisely locate the optimal duty cycle to regulate power flow in PV cells19. However, optimization algorithms are not without limitations, as they can become trapped in local maxima, exhibit poor responsiveness to changing weather conditions, and struggle with exploration and exploitation during the search process. Specifically, these algorithms often face difficulties in updating particle positions within the convergence region to find the global best position20,21. Additionally, the mathematical equations governing the iterative updates of duty cycles until the stopping criterion (such as maximum iterations) is met pose another challenge, often resulting in suboptimal performance under certain conditions20,21.

Flowchart of optimization techniques22.

Another drawback is the time (number of iterations) consumed by GMPPT algorithm search particles (population or swarms) to successfully converge, that is, when the absolute difference between the particle best fitness \(fitnessPbest\left( u \right)\) power and the global best fitness \(\left( {fitnessGbest} \right)\) power falls below the stipulated tolerance value equivalent to one-hundredth of the theoretical GMPPT power as used in recent research papers that contribute to global maximum power point tracking developments in PV systems23,24. This article focuses on improvising an improved Jellyfish search optimization (IJSO) technique capable of responding intermittently to sudden changes in weather conditions, and suitable for extracting solar cell parameters needed in PV cell modelling and as well enhance the flow of electrical power in PV cells or array working at different atmospheric conditions. This paper proposes an improved Jellyfish Search Optimization (IJFO) algorithm that outperforms the original Jellyfish Search Optimization (JSO) algorithm. The improved algorithm enhances the convergence rate and maintains a better balance between exploration and exploitation. Unlike the original JSO technique, which can get trapped in local minima during the exploration phase, the improved algorithm is more robust and effective in navigating the solution space, thus avoiding premature convergence.

The rest of this article is prearranged as follows. Section 2 presents the mathematical modelling of photovoltaic cells using five parameters, seven parameters, and nine parameters equivalent circuit models. Section 3 will be a brief description of the suggested IJSO technique, and a review of other recent optimization techniques considered for solving both minimization and maximization problems and their extended applications in photovoltaic system. Section 4 presents the experimental procedure using six different scenarios as case studies. Section 5 provides the outcomes and deliberations, and Sect. 6 would be the conclusion.

2. Mathematical modelling of photovoltaic cells

Solar cells are semiconductor materials used to convert sunlight energy to other forms of energy such as electric and heat energy25. A basic cell consists of photodiode(s), resistors, positive and negative junctions for the deposition of free electrons and holes absorbed from sunlight energy26. Figure 2 signifies a corresponding circuit of a single diode cell modelled using five parameters27. In this model, the five parameters are photon current \(\:\left({I}_{ph}\right)\), reverse saturated current of diode D1\(\:\left({I}_{s1}\right)\), series resistance \(\:\left({R}_{s}\right)\), shunt resistance \(\:\left({R}_{sh}\right)\:\)and diode ideality factor \(\:\left({A}_{1}\right)\). 5-parameter cell is an approximate to a practical cell with an output current \(\:\left({I}_{calculated}\right)\) expressed using Eq. (1) for a single cell and Eq. (2) for multiple cells connected in series28,

where \({I_{total}},{I_{D1}},{I_R},{V_t},V{\text{ and }}I\) represent the total PV cell current, current across diode D1, current across the series resistance R, thermal voltage, measured cell voltage and the measured cell current respectively.

Figure 3 illustrates the corresponding circuit for a two-diode cell modelled using seven parameters topology29,30. This prototype is assumed to be more accurate than a single-diode cell due to the impact of reverse saturation current \(\:\left({I}_{s2}\right)\) and the ideality factor, A2, measuring the diode proximity in comparison with the ideal diode equivalence31. However, with the additional variables comes complexity as seven-parameter cells appear to be more intricate and computational-demanding than a single diode cell with five parameters32,33. Equation (3) expresses the calculated current \(\:\left({I}_{calculated}\right)\:\)for a two-diode cell whereas Eq. (4) is the cumulative output current (calculated) for solar panels with\({N_s}\)(number of series-linked cells) and with the supposition that the number of parallel-connected cells ,\(\:{N}_{p}\), remains at unity34,35,36.

Figure 4 displays the comparable circuit of a three-diode cell developed using nine-parameters \(\:\left({I}_{ph},{I}_{s1},{A}_{1},{I}_{s2},{A}_{2},{I}_{s3},{A}_{3},{R}_{s},\text{\:and\:}{\text{R}}_{sh}\right)\). In addition, this model addresses the grain boundary losses and current leakage losses experienced with practical cells and is considered more complex than a two-diode cell due to the inclusion of another two additional parameters \(\:\left({I}_{\text{s3}}\text{\:}\right)\:\)referred to as the reverse saturation current across diode D3 and, \(\:{\text{A}}_{3}\), known as the ideality factor for diode D3. Similarly, the mathematical formula for a 3-diode cell is described using Eqs. (5)–(6), while the total current for multiple cells connected in series can be defined using Eq. (7)37.

where ID2 and ID3 is the current across diode D2 and D3.

Optimization methods

The four optimization algorithms considered in this article for case studies are Mayfly optimization algorithm, (MOA), Harris Hawk optimization (HHO), flying Squirrel search optimization (FSSO) and the proposed improved Jelly Fish search optimization (IJSO). A brief review of the considered optimization techniques is discussed as follows:

Mayfly optimization algorithm

Mayfly Optimization (MFO) algorithm is a population-based and bio-inspired metaheuristic optimization technique presented by K. Zervoudakis and S. Tsafarakis in 2020 for solving both continuous and discrete optimization problems38. MFO mimics the flying and breeding behaviour of adult mayflies as candidate solutions in solving optimization problems39. MFO is categorized as a hybrid algorithm combining swarm intelligence and evolutionary behaviour of three known algorithms comprising of particle swarm optimization (PSO), firefly algorithm (FA), and genetic algorithm (GA) techniques as a single-objective technique40,41. For the movement behaviour, the mayfly algorithm uses a PSO or firefly pattern-like attribute to convey both male and female mayflies for mating process, that is in-turn completed using GA pattern-like characteristics to produce new Mayfly offspring. The mathematical model of MFO is discussed below42:

Movement of male mayflies

Equations (8)–(9) presents the mathematical computation involved for the movement of male mayflies towards the female mayflies using nuptial dance parameter,

where

Movement of female mayflies

Like the male mayflies, Eqs. (12)–(14) illustrate the female mayflies’ transitional movement towards the male mayflies for mating to provide new offspring43.

Mating of fireflies

New offspring genes and chromosomes are shared using Eqs. (14),

where parentmale and parentfemale represent the male and female parents, and K is a random parameter with values between 0 and 1. In the same way, to implement the MFO algorithm for tracking global-best duty cycle position in PV systems, \(\:{x}_{i}^{k}\text{\:and\:}{x}_{i}^{k+1}\:\)are replaced with current duty cycles \(\:,{d}_{i}^{k}\text{\:and\:updated\:duty\:cycle\:}{d}_{i}^{k+1}\:\)While assigning values of 0.1 and 0.9 to boundaries \(\:{l}_{b}\text{\:and\:}{u}_{b\:}\)as the duty cycle searching space respectively44,45,46,47,48.

Harris Hawk optimization algorithm

Harris Hawk optimization (HHO) algorithm is a recent, nature-inspired technique introduced by Heidari et al.49. The algorithm imitates the random-searching (exploration), mutual pounce-hunting strategies (exploitation) of Harris hawk birds when predating on escaping prey that is often Rabbits as food50. Naturally, Harris Hawk uses a switching tactic, both hard and soft besiege and attacks from different directions to confuse, weaken and kill its prey, and have the food source shared with other party members48. The exploitation phase in the HHO algorithm consists of four phases described as ‘the soft besiege, hard besiege, soft besiege with progressive rapid drive, and the hard besiege with progressive rapid drive51. Like conventional jellyfish swarm optimization, the HHO algorithm is parameterless and only relies on the random distribution probability as the only variable for changing phases to ensure the candidate solution is located. Mathematically, both the exploration process and the transition from exploration to exploitation using the four-mentioned phases are expatiated further using the equations below52,53:

where \({E_0}=2*rand - 1\) is the initial escape energy with values between \(\:-1\text{\:and\:}1\). Variables \(\:E,k,{k}_{max}\:\)represent the escape energy, current iteration, and maximum iteration respectively and rand is a uniformly distributed random numbers with values between 0 and 1.

Exploration phase \(\:\left(\left|E\right|\ge\:1\right)\)

At this phase, where the value of escape energy is 1 or exceeds 1, the algorithm attempts to evaluate candidate solutions that are not neighbours to the current solution(s) using Eqs. (16)–(17),

Exploitation phases \(\:\left(\left|E\right|<1\right)\)

At this phase, where the absolute value of the escape energy is lesser than 1, the algorithm searches for the global best solution among candidate solutions that are neighbors to the current solutions using these four phases formula:

Soft Besiege, when \(\:\left(\left|E\right|\ge\:0.5\text{\:and\:}r\ge\:0.5\right)\)

Hard Besiege, when \(\:\left(\left|E\right|<0.5\text{\:and\:}r\ge\:0.5\right)\)

Soft Besiege with progressive rapid dives (PRD), when \(\left( {\left| E \right| \geqslant 0.5{\text{ and }}r<0.5} \right)\)

Hard besiege with progressive rapid dives (PRD), when \(\:\left(\left|E\right|<0.5\text{\:and\:}r<0.5\right)\)

Variables \(\:\left(\text{r},{\text{r}}_{1},{\text{r}}_{2},{\text{r}}_{3},{\text{r}}_{4},\text{\:and\:}{\text{r}}_{5}\right)\:\)are uniformly distributed arbitrary numbers with values between 0 and 1. parameters\(\:\:{\:\text{x}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{k}},{\text{x}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{k}+1},{{\text{x}}^{\text{k}}}_{\text{r}\text{a}\text{b}\text{b}\text{i}\text{t}},{\text{x}}_{\text{m}\text{e}\text{a}\text{n}}^{\text{k}},\text{\:and\:}\text{J}\:\)denote the current position, updated position of the predator (Harris Hawk), the prey (Rabbit) position or global best position or candidate solution, the mean position at iteration k, and the Rabbit random jump strength correspondingly54. For MPPT tracking in PV systems, the HHO algorithm can also be applied by substituting the vector position \(\:\left({x}_{i}\right)\:\)with duty cycle positions with searching space between 0.1 and 0.953,55.

Flying Squirrel search optimization (FSSO)

Flying Squirrel search optimization (FSSO) technique is an improved prototype of the novel Squirrel search optimization (SSO) technique originally developed by Jain et al. in 2019 and recently modified by Y. Wang and T. Du56,57. FSSO is a swarm-based, nature-inspired algorithm imitating the active slide movement of southern flying Squirrels commonly found in an old forest environment58. FSSO uses allotted random positions generated from a uniform distribution to denote the initial positions of the flying squirrels and with corresponding fitness value as the quality of food source for each flying squirrel respectively. To solve optimization problems, flying Squirrel positions are split into three regions while following three basic phases depending on the fitness value59. The three-mentioned regions are classified categorically as “the region with sets of optimal solution (OS-region), a region near-optimal solution (NOS-region), and the region with random solution (RS-region)60. Furthermore, the three operational steps involved with the FSSO algorithm are enumerated as follows59,61,62:

-

For the first step, the near-optimum-solution (NOS) particles move in the path determined by the best candidate.

-

The next is splitting the random-solution (RS) particles to allow the movement of some fold toward the optimal solution (OS).

-

For the third step, the remaining RS particles move towards the NOS particles.

while exploiting the best candidate solutions, some of the FSSO particles from the entire population transit from \(\:normal\_tree\to\:acorn\_tree\to\:hickory\_tree\) using a parameter referred to as “the predator presence probability \(\:\left({P}_{dp}\right)\)” analyzed using Eqs. (26)–(29)63.

where \(\:{d}_{i},{N}_{fs},{d\text{\:and}{\text{\:}}_{max}}_{min}\:\)signify the current position of flying squirrel \(\:i\), number of flying squirrels, lower boundary and the upper boundary searching space respectively.

Seasonal monitoring conditions (exploitation phase).

Condition 1

Condition 2

Condition 3

where \(\:{g}_{d}=\frac{{h}_{g}}{{s}_{f}{tan}\varphi\:}\), \(\:{tan}\varphi\:=\frac{{f}_{d}}{{f}_{l}}=\frac{0.5\rho\:{V}^{2}S{C}_{d}}{0.5\rho\:{V}^{2}S{C}_{l}}\), \(\:{S}_{c}^{k}=\left|{d}_{at}^{k}-{d}_{ht}\right|\), and \({S_{\hbox{min} }}=\frac{{10{e^{ - 6}}}}{{{{365}^{\frac{{2.5k}}{{{k_{\hbox{max} }}}}}}}}\)

\({h_g} = 1\;{\rm{m}}; {s_f} = 18; \rho = 1.204\;{\rm{kg/}}{{\rm{m}}^3}; V = 5.25\;{\rm{m/s}}; S = 154\;{\rm{c}}{{\rm{m}}^2}; {C_d} = 0.6; {C_l} = 0.7; {P_{dp}} = 0.1; {G_c} = 1.9\)

Variables \(\:{d}_{nt},{d}_{at},{d}_{ht}\)are the normal tree, acorn tree, and hickory tree solutions while variables \(\:{r}_{1},{r}_{2},\text{\:and\:}{r}_{3}\) are random numbers distributed uniformly between 0 and 1. \(\:{\text{g}}_{\text{d}}\:\)denotes the gliding distance and \(\:{\text{G}}_{\text{c}}\) is the gliding constant with a value of 1.9. \(\:{h}_{g},{s}_{f},\phi\:,\rho\:,V,S,{C}_{d},\text{\:and\:}{C}_{l}\) denote the height loss after gliding has occurred, scaling factor, tangential angle, air density, velocity of squirrel, surface area, drag coefficient and the lift coefficient respectively. For better exploration, Eqs. (30) and (31) display how flying squirrels situated at normal tree positions are updated with the aid of Lévy flight\(\:\left(s\right)\) movement,

Exploration phase

Improved Jellyfish search optimization (IJSO)

IJSO is a hybrid algorithm combining the functionality of Jellyfish search optimization (JSO) and Cuckoo search (CS) algorithm as a single algorithm. Jellyfish search optimization is a recent bio-inspired metaheuristic optimization technique developed by Jui-Sheng Chou et al. in 202164,65. The IJSO algorithm imitates the foraging behaviour of Jellyfish in the sea while the CS algorithm is a nature-inspired optimization algorithm developed by Yang et al. in 2009, mimicking the coevolution behaviour of some cuckoo bird species. The improved jellyfish search optimization (IJSO) algorithm works by first enacting the fast-problem-solving performance of the JSO algorithm as the initial candidate solution. This initial solution is then further amended by allowing the shift of particles situated at worse particle vector positions from the entire population to iteratively change their vector positions to a better position using the amalgamated CS algorithm to successfully locate the best candidate solution. This methodology seems promising and can be recommended for solving different kinds of minimization and maximization optimization problems. Another advantage of the improved IJSO is that the algorithm works extensively with zero-arity as tuning parameters are not required to work, unlike some other optimization techniques such as PSO and Mayfly optimization. The IJSO’s fast exploration and exploitation capabilities are achieved using these three basic rules66,67:

-

Jellyfish trails and uses a time-control mechanism, \(\:{C}_{k},\:\)for changing its drives (ocean drive for local search and swarm drive for exploitation) while searching for food particles. This switching mechanism, \(\:{C}_{k},\:\)allows the algorithm to initially exhibit more of local-search characteristics, which in time changes to exploitation as \(\:{C}_{k}\) decreases due to an increment in the number of iterations.

-

While seeking for food particles in the sea, Jellyfishes are more concerned to environments with higher quantities of food.

-

The quantity of food located by Jellyfishes depends on the food position and its equivalent fitness function.

-

A cuckoo-search discovery probability (P) can be used to locate and improve the worst JSO candidate solution to a better solution.

Similar to a conventional JSO technique, the exploration phase occurs when a Jellyfish follows the ocean current in search of food position \(\:\left({x}_{gbest}^{k}\right)\) and using Eq. (33), while exploitation phases are the active and inert movement of jellyfishes inside the swarm calculated using Eqs. (34)–(36)68,

Exploration phase

Equation (33) is the mathematical formula for ocean current, \(\:\left(when\:\left|{C}_{k}\right|\ge\:{C}_{0}\right)\)

Exploitation phase (movement inside the swarm) when $$\:\left|{C}_{k}\right|<{C}_{0}$$

This movement is further re-distributed as passive and active motion.

The passive (type A) motion \(\:\left(when\:{r}_{3}>\left(1-{C}_{k}\right)\right)\) is expressed using Eqs. (34),

where variables\(\:\:\left({\upgamma\:},{\text{c}}_{0},\text{\:and\:}{\upbeta\:}\right)\:\)represent the movement coefficient, threshold constant, and distribution coefficient with values of 0.1, 0.5, and 3 respectively, \(\:\text{k}\)is the iteration number, \(\:{\text{k}}_{\text{m}\text{a}\text{x}\:}\)is the maximum iteration, and \(\:\left({\text{r}}_{1},{\text{r}}_{2},{\text{r}}_{3},\text{\:and\:}{\text{r}}_{4}\right)\:\)are random numbers that are uniformly distributed between 0 and 1. \(\:\left({\text{x}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{k}},{\text{x}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{k}+1},{\text{x}}_{\text{p}\text{b}\text{e}\text{s}\text{t}}^{\text{k}},{\text{x}}_{\text{m}\text{e}\text{a}\text{n}}^{\text{k}},{\text{u}}_{\text{b}},\text{\:and\:}{\text{l}}_{\text{b}}\right)\:\:\)denote the current, updated particle position, current best-particle position, mean position, upper boundary limit, and the lower boundary searching space respectively69.

The Active (type B) motion \(\:\left(when\:{r}_{3}\le\:\left(1-{c}_{k}\right)\right)\:\)is described using Eqs. (35),

where \(\:\text{s}\text{t}\text{e}\text{p}\:\)is the distance apart between \(particle - i\)with fitness functions \(\:\text{f}\left({\text{x}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{k}}\right)\) and \(particle - j\)with fitness function \(\:\text{f}\left({\text{x}}_{\text{j}}^{\text{k}}\right)\),

For the MPPT task, the modified JSO algorithm is workable by replacing the vector position \(\:\overrightarrow{x}\) with duty cycle position, \(\:\overrightarrow{d}\), and boundary constraints \(\:{u}_{b}\text{\:and\:}{l}_{b}\) with values of 0.9 and 0.1 respectively41,70,71. Figure 5 displays the flow diagram of the IJSO algorithm for the MPPT task and its corresponding pseudocode is described in the next section below.

Simulation setup

To evaluate the performances of the proposed IJSO algorithms along with other three existing algorithms comprising of HHO, MFO72,73 and FFSO techniques discussed in Sect. 3, three experiment analyses were led to assess the potentials of these algorithms for solar cell modelling and maximization of power in PV system. That is, for minimization, two different cases were considered (known functions benchmarking and solar cells parameters extraction), while power maximization in PV cells was considered for the third experimental analysis for maximization application. In expansion, the benchmarking experiment will be assigned as case study 1, solar cell parameter evaluation using five parameters, seven parameters and nine-parameters as the second case study. Case study 3 will be maximization of power energy from photovoltaic modules working at standard test conditions (STC) for maximum power point tracking. Case study 4 will involve power analysis on photovoltaic systems using different partial shading patterns and dissimilar cell materials to evaluate the response rate for each algorithm for GMPP tracking, case study 5 will focus on maximization of power from PV emulators while case study 6 will focus on energy-harvest from PV systems using historical real-time data of a particular area in Bloemfontein, South Africa. Table 1 gives a quick summary of the MFO algorithm control parameters and their parameterized values while Table 2 displays the FSSO algorithm parameters. These experimental analyses were conducted using MATLAB/Simulink programming software while the real-time weather data were collected using PVSol software.

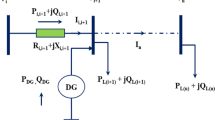

IJSO and HHO algorithms are considered parameter-less. However, these algorithms still require three common parameters used for initializing optimization algorithms. The first is the “number of trials” for robustness check due to the random solution-searching behaviour with optimization algorithms, the second is the “number of population or searching agents (npop)” and the third is the “maximum number of iterations (itermax)” per trial as a stopping criterion. The IJSO algorithm Pseudocode is provided in Fig. 6 while Fig. 7 is a block diagram of the complete PV system used in this paper.

Case Study 1 (benchmark function test)

For the benchmark test, minimization was executed using six test functions labelled F1 – F6 with each function exhibiting a unique characteristic (different local minima and different physical descriptions). For robustness check, these test functions were tried 100 times and using 50 searching agents and 3000 iterations per trial as the stopping criterion. The respective fitness values for the process and the simulation time taken to complete the 100 trials were recorded and compared with their corresponding theoretical global fitness values to validate the effectiveness of these algorithms for minimization problem-solving capabilities. Equations (37)–(42) are the mathematical functions for the benchmark function denoted as F1, F2, F3, F4, F5, and F6 individually.

where \(\:\beta\:\text{\:and\:}C\:\)in \(\:F2\:\)are \(\:d-\text{dimesion}\)vector and \(\:4\times\:d-\text{dimension\:}\)matrix respectively. Variable \(\:\alpha\:\:\)notes another 4-dimensional vector, while variables \(\:\left(A\text{\:and\:}P\right)\) are sets of \(\:4\times\:d-\)dimensional matrix in F3, and \(\:\alpha\:\:\)in F5 represents a \(\:\left(2\times\:25\right)-matrix\). Table 3 provides the function details, and the global minima recorded from studies

Case study 2 (solar cell’s parameter extraction)

To investigate the efficacy of the anticipated IJSO algorithm alongside the other three existing techniques comprising of Mayfly optimization (MFO), Harris Hawk optimization (HHO), and the flying Squirrel search optimization (FSSO) for finding the best input parameters in a five-parameter cell, seven-parameter cell, and a triple-diode nine-parameter solar cell, the following methodologies were instituted:

Firstly, for the single diode cell comprising unknown input parameter values \(\:{I}_{ph},{I}_{s1},{R}_{s},{R}_{sh},and\:{A}_{1}\) evaluated using the above-mentioned optimization algorithms, a cost function equal to the root-mean-square-error (RMSE) change amid the measured PV current \(\:\left({I}_{measured}=I\right)\) and the calculated PV cell current \(\:\left({I}_{calculated}\right)\) is introduced. The measured PV current samples were collected from a real-time measurement while the calculated PV current \(\:\left({I}_{calculated}\right)\) was computed by applying the 5-parameter optimized candidate solutions to the 5-parameter equivalent-circuit mathematical equation provided in Eqs. (1) and (2) of this paper respectively. Furthermore, for validation standard, solar cells from three dissimilar cells technologies, operating at different cell temperatures and exhibiting different characteristics were employed. That is, RTC France solar cell with 26 measured current-voltage (I – V) datapoints operating at 306 K cell temperature and 1 kW/m2 light intensity for the monocrystalline, PVM 752 GaAs photovoltaic cell operating at standard test conditions (STC) and with 44 measured I – V datapoints for the thin film cells, and 26 measured I - V samples using a single-module Photo watt PWP201 solar panel comprising of 36 polycrystalline cells per module and operating at 1 kW/m2 insolation and 318 K temperature for the polycrystalline cell(s) were administered. Like case study 1, each algorithm was tried 100 times and using 3000 iterations per trial as the stopping criteria. The best solution, worst solution, mean fitness solution, and their respective positions (parameter’s value) were also recorded for comparison. Table 4 displays the considered cell manufacturers’ names and their respective search-space values.

For the double-diode cell with seven parameters labelled \(\:{\text{I}}_{\text{p}\text{h}},{\text{I}}_{\text{s}1},{\text{I}}_{\text{s}2},{\text{A}}_{1},{\text{A}}_{2},{\text{R}}_{\text{s}},\text{\:and\:}{\text{R}}_{\text{s}\text{h}}\), the same methodology as the 1-diode cell with five parameters is observed but using Eqs. (3) and (4) to compute the RMSE that best provides solutions to the errors between the measured currents and the calculated currents while keeping cell voltages unaltered for both measured and calculated data. Table 5 presents the constraint limit for the seven parameters in a two-diode cell developed using RTC France monocrystalline cell, PVM 752 GaAs thin-film cell, and Photo watt PWP 201 polycrystalline modules respectively.

For the 3-diode cells comprising of nine-parameters \(\:{\text{I}}_{\text{ph}},\,\,{\text{I}}_{\text{s}1},{\text{A}}_{1},{\text{I}}_{\text{s}2},{\text{A}}_{2},{\text{I}}_{\text{s}3},{\text{A}}_{3},{\text{R}}_{\text{s}},\text{\:and\:}{\text{R}}_{\text{s}\text{h}}\). similar to Tables 5 and 6 presents the boundary constraint used to investigate the efficacy of the proposed algorithms using a 3-diode cell with nine unknown parameters seeking candidate solution using optimization techniques.

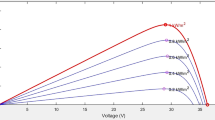

Case study 3 (power maximization from similar modules at STC)

For this case study 3a, the PV system block diagram discussed earlier using Fig. 10 is implemented using five series-connected ET-654,200 WW solar panels with 200 W rated STC manufacturer power rating across each panel and with a uniform insolation of 1000 W/m2 striking each panel at a maintained room temperature of 298 K. Figures 8 and 9 are graphical depictions interpreting the theoretical I – V and the P – V (power - voltage) curve with a peak power \(\:\left({\text{P}}_{\text{m}\text{p}\text{p}}\right)\:\)of \(\:1001.33\:\text{W}.\:\)In this study, we aim to develop an effective GMPP tracker that best maximizes power supply from the PV array system using the considered algorithms.

Similarly, another series-connected configuration referred to as case study 3b was set using five series-connected Soltech 1STH-215P panels with a rated power of 215 W across each panel and with a uniform irradiance (G) of 1000 W/m2 striking across each panel and at a regulated temperature of 298 K. Figures 10 and 11 are the manufacturer’s theoretical I – V and P – V curves with a maximum theoretical total power (Pmpp) of 1001.33 W for the 5 series-connected Soltech 1STH-215P panels operating at STC.

Case study 4 (dissimilar shading patterns)

For this case scenario, three dissimilar array patterns are considered as case studies 4a, 4b, and 4c.

Case study 4a (shading pattern 1)

For Case study 4(a), Figs. 12 and 13 display the theoretic I - V and P - V characteristics for another PV system constituting of four series-connected TP250MBZ panels with a theoretical peak power of 638.5 W and a rated STC power of 249 W for each panel. The irradiances across these panels were non-uniform. That is, 1000\({\text{W}}{{\text{m}}^{ - 2}}\)illumination striking both panel 1 and panel 2, 800\({\text{W}}{{\text{m}}^{ - 2}}\)for panel 3, and 500\({\text{W}}{{\text{m}}^{ - 2}}\)for panel 4 at a steady room temperature of 298 K across each module.

Case study 4b: (shading pattern 2)

For Case study 4(b), Figs. 14 and 15 illustrate the I-V and P-V properties for five series-connected ET-P654200WW polycrystalline panels with a theoretical peak power of 667 W and a manufacturer-rated power of 200 W for each panel at STC. The irradiance across these panels was also non-uniform. Specifically, 600\({\text{W}}{{\text{m}}^{ - 2}}\)illumination signal striking the first panel, 700 \({\text{W}}{{\text{m}}^{ - 2}}\) for the second panel, 800\({\text{W}}{{\text{m}}^{ - 2}}\) for the third panel, 900\({\text{W}}{{\text{m}}^{ - 2}}\)on panel 4, and 1000\({\text{W}}{{\text{m}}^{ - 2}}\)across the fifth panel at a stable temperature of 298 K.

Case study 4c (power maximization from dissimilar modules)

For Case Study 4c, four series-connected solar panels from different producers were utilised. The purpose of this trial is to examine how the considered algorithms will successfully locate the GMPP under non-uniform irradiance conditions from dissimilar photovoltaic cell materials. In detail, the LG375N2C-B3 monocrystalline-cell panel with a manufacturer power of 375.18 W operating at STC was installed as panel 1. For the second panel, Photo watt PW2750-285 polycrystalline-cell with 284.894 W rated power and sensing 900\({\text{W}}{{\text{m}}^{ - 2}}\)insolation and 298 K temperature were used. For panel 3, Q – Q-smart UFL 105 thin-film cells with 105.11 W rated power, and operating at 700 W/m2 irradiance and 25 °C temperature were considered. For the fourth panel, REC380TP2SM 72 passive emitter and rear cell solar panel working at 550\({\text{W}}{{\text{m}}^{ - 2}}\)insolation and 25 °C temperature and with a rated STC panel power of 284.894 W was allotted. Figures 16 and 17 demonstrate the I-V and P – V properties for the arrayed panels and with a maximum theoretical array power of 655.99 W.

Case study 5 (maximization of power from PV emulators)

This research was piloted to assess the success of the proposed IJSO algorithm using photovoltaic emulators (PVE). Figures 18 and 19 show the I – V and P – V properties of a PVE power source with a theoretical power of 85.1 W under partial shading conditions (PSC). The PVE was carefully chosen for the trial because of its compactness, low operation cost and simple re-shaping procedure compared to practical cells or panels that are affected by unstable global horizontal irradiance (GHI). The PVE was modelled using 1-Dimensional I – V look-up Table comprising of 10,910 rows \(\:\times\:\:\)2 columns samples. Column 1 is the first - data column with 10,910 cell current samples identified as ‘the breakpoint data’. Column 2 is the second – data column with 10,910 voltage data referred to as ‘Table data’.

Case study 6 (power optimization under fluctuating weather conditions)

This case study experiment was initiated to evaluate and compare the response rate of the proposed IJSO, HHO, FSSO and MFO algorithm to changes in weather conditions using annual historical weather data of a particular site (Bram Fischer International Airport, Bloemfontein) in South Africa with latitude and longitude coordinates \(\:\left(-29.092736^\circ\:\text{\:and\:}26.298767^\circ\:\right)\:\)respectively. The annual report data was collected using the Solcast weather forecasting toolkit and analyzed using PVsyst software. For simplicity, the global horizontal irradiance (GHI) and the ambient temperature (Tambient) information during peak insolation hours (sunrise to sunset) for two-different season dates, (3rd July 2022) during winter and (3rd February 2023) in summer were considered for this task. Figures 20 and 21 present the GHI values and the ambient temperature recorded from 6 am (sunrise) till 5 pm (sunset) on the 3rd of July 2022 for PV system power flow during winter. To calculate the average daily savings using solar energy, the following mathematical formulas used by Eskom, a South African public electricity utility supplier were applied for both household premises and business premises.

\(Estimated\_Energy=mean~power \times 10{\text{~hours~~}}\left( {{\text{peak~hours~from~}}6am - {\text{sunrise~till~}}4pm - {\text{sunset}}} \right)\)

\(Saving{s_{household\left( {vat\_exclusive} \right)}}=Estimated\_Energy \times Eskom\_{\text{Household\_Electricity~}}Rate{\text{~per~}}kWh\)

\(\begin{aligned} Savings_{{household\left( {vat\_inclusive} \right)}} = & Savings_{{household\left( {vat\_exclusive} \right)}} + 15\% ~{\text{VAT}}_{{South~Africa}} ~ \\ & \times Savings_{{household\left( {vat\_exclusive} \right)}} \\ \end{aligned}\)

\(Saving{s_{{\text{business}}\left( {vat\_exclusive} \right)}}=Estimated\_Energy \times Eskom\_{\text{Business\_Electricity~}}Rate{\text{~per~}}kWh\)

\(\begin{aligned} Savings_{{{\text{business}}\left( {vat\_inclusive} \right)}} = & Savings_{{{\text{business}}\left( {vat\_exclusive} \right)}} + 15\% ~{\text{VAT}}_{{South~Africa}} ~ \\ & \times Savings_{{{\text{business}}\left( {vat\_exclusive} \right)}} \\ \end{aligned}\)

where \(Saving{s_{household\left( {vat\_exclusive} \right)}}\) and \(Saving{s_{{\text{business}}\left( {vat\_exclusive} \right)}}\) are the amount saved (excluding value-added tax (VAT)) using five-series connected ET-654200WW solar panels for home use and business use respectively. \(\:Eskom\_\text{Household\_Electricity\:}Rate\) is the electricity rate for home use at a current value of R2.78 per kWh for households while \(\:Eskom\_\text{Business\_Electricity\:}Rate\) is for business owners at a rate of R1.33 per kWh. \(\:Saving{s}_{household\left(vat\_inclusive\right)}\) and \(\:Saving{s}_{\text{business}\left(vat\_inclusive\right)}\)are amount saved (VAT inclusive) for electricity for home use and business use respectively.

Similarly, Figs. 22 and 23 present the GHI and the ambient temperature recorded from 4 am (sunrise) till 6 pm (sunset) on the 3rd February 2023 during the summer season at the Bram Fischer international Airport, Bloemfontein, South Africa.

Experimental results and discussions

The results for the six case studies described in Sect. 4 are presented and discussed below.

Case study 1 results

Table 7 displays the fitness results for the algorithms and the time taken to complete 100 trials using 3000 iterations per trial. Comparing the fitness results (fitnesscalculated) obtained in this Table with the theoretical solutions provided in Table 3, and using the absolute error \(\:\left(\left|fitnes{s}_{calculated}-fitnes{s}_{theoretical}\right|\right)\) for correlation. It is observed and suggested that the small iteration-number (3000 iterations) stopping criterion used in this study could have caused the algorithm’s inability to locate the global optimum with high precision in some benchmarks. Still, it can be deduced that IJSO overperforms in all the benchmarking experiments that were conducted, followed by HHO algorithm. On the other hand, MFO displayed the weakest performance and took the longest possible time to complete its execution in most benchmark testing.

Case study 2 results

The results for the extraction of parameters from a five-parameter, seven-parameter and nine-parameter equivalent circuits are discussed and analyzed as follows:

Case study 2(a) results

Tables 8, 9, and 10 display the tabulated results obtained using FSSO, HHO, MFO, and IJSO techniques for solar cell parameter extraction in three different PV cells (RTC-France, PVM, PWP cells) modelled using 5-parameters cell strategies. Furthermore, Table 11; Figs. 24, 25, and 26 display the contingency test results collected using the overall-best-performing (IJSO) worst global-best fitness results and the overall-least-performing worst global-best fitness results and their respective worst candidate solution. These datasets were further used extensively to generate a fitting relationship between actual I datapoints and its worst-predicted I -V counterpart. That is, the worst fitness values recorded in Tables 8, 9, and 10 were used to collect the respective five-parameter cell values used to compute the corresponding calculated current using Eqs. (1)–(2), while keeping the voltage un-altered.

For Table 8 results collected using 5-parameters RTC France cell model, it is validated that IJSO demonstrated the best performance with a RMSE of 9.861E-04, best-worst fitness of 1.4385E-03, mean RMSE of 9.91E-04, and a standard deviation (STD) value of 4.52E-05, thus confirming the fast exploration and exploitation (convergence) the IJSO algorithm and using the shortest possible time (367.59 s) to complete 100 runs. Conversely, HHO and FSSO exhibited weak exploration and exploitation performances while MFO exhibited a delayed exploitation performance as it took the longest simulation time (1022.72 s) to complete its 100-trials iteration process.

For Fig. 24, using the worst RMSE value and the corresponding worst global-best position (candidate solutions) of IJSO and FFSO techniques as parameters for calculating the RTC cell theoretical I-V samples evaluated using 5 – parameters cell knowledge, in conjunction with the actual I-V samples of RTC cell as measured samples. From the graph, the precision using IJSO even at worst-case can be seen as most samples collected using IJSO fit properly with the 26 measured I-V samples. Conversely, the poor performance using FFSO can be observed as all 26 samples recorded were in contrast with the measured I-V samples simulated at 1 kW/m2 insolation and 306 K temperature.

Similarly from Table 9, results collected using 5-parameters PVM cell technology, IJSO displayed the overall best performance with a best fitness value of 2.2781E-04, worst fitness value of 2.7008E-04, mean fitness of 2.2823E-04, and a standard deviation of 4.23E-06 completed using 451.159 s while FSSO demonstrated the overall-worst performance with 2.7496E-04 as the best fitness, 8.3219E-02 worst fitness, 1.6896E-02 mean fitness and a STD value of 2.3604E-02 for the 100-runs completed in 887.333 s. MFO exhibited the second-best performance but consumed longer time (1158.960 s) to complete its 100-run iterations process.

For Fig. 25, using the worst RMSE value and the corresponding candidate solutions for IJSO and FFSO algorithms as parameters for calculating the PVM cell theoretical I-V samples evaluated using 5–5-parameter cell information. From the graph, the high accuracy with IJSO technique can be observed as most samples collected using IJSO fit properly with the measured I-V curve. Conversely, the poor performance using FFSO can be observed as most samples calculated were in contrast and only 1 sample out of the entire 44 samples corresponds with the measured PVM I-V curve at standard test conditions (1 kW/m2 irradiance and 306 K cell temperature).

From Table 10 results collected using a 5-parameters PWP panel, IJSO presented the overall-best performance with a superlative fitness value of 2.4267E-03, worst fitness value of 2.4267E-03, the mean fitness of 2.4267E-03, and a STD value of 1.4700E-11 completed using 374.564 s while FSSO established the overall-worst performance with a value of 2.5193E-03 as the best-fitness, 2.84E-02 worst fitness, 3.3202E-02 mean fitness and a STD value of 5.6435E-02 for the 100-runs completed in 750.379 s.

For Fig. 26, using the Photowatt-PWP201 module I-V dataset, the high accuracy with the IJSO technique is displayed as all samples collected using IJSO align with the measured I-V curve. On the other hand, FFSO exhibited a poor performance as most samples calculated failed to align with the actual data sample, and only 1 sample out of the entire 26 samples collected corresponded with the measured PWP I-V curve at 1 kW/m2 irradiance and 318 K cell temperature.

Case study 2(b) results

Similar to case 2(a), Tables 12, 13, and 14 display the tabulated results for FSSO, HHO, MFO, and IJSO algorithms modelled using 7-parameter equivalent circuits for three different cell technologies while Table 15; Figs. 27, 28, 29 present the contingency test results collected using the worst global-best values of the best performing algorithm (IJSO) compared to the worst global-best of the worst performing algorithm (FSSO), in-lieu with the manufacturer measured current-voltage (I-V) data to demonstrate how constructive optimization techniques can be used to evaluate cell parameters.

For Table 12, using 7-parameter RTC France solar cell, findings show that IJSO displayed the finest performance with a value of 9.8413E-4 as the global-best fitness value, 9.86E-04 as worst fitness, 9.8417E-04 mean fitness, 2.38E-07 STD measure using the shortest possible time (243.534 s) to complete the 100-runs iteration process. In contrast, FSSO demonstrated the worst performance with a global-best fitness value of 1.1573E-03, worst global-best fitness value of 6.307E-01, mean global-best fitness value of 6.3372E-02, STD value of 9.7598E-02 and 758.373 s simulation run-time. Furthermore, in terms of locating the global-best fitness, MFO is a second runner-up but with a longer simulation run-time and lower STD measure of convergence value of 1.4223E-03 compared to HHO.

Similarly, For Figs. 27, 28, 29, modelled using 7-parameter RTC France cell, PVM cell and Photowatt-PWP201 module I-V datasheet samples, it can be observed that IJSO outperformed FFSO as the calculated data points using IJSO techniques were a perfect match to the corresponding measured I-V samples for the three cell models worked on. whereas FFSO underperformed with just one or two samples coinciding with the measured I-V curve samples.

For Table 13, using 7-parameter PVM cells as a case study, findings show that IJSO exhibited the best performance with a value of 2.0276E-04 as the global-best fitness value, 2.2281E-04 worst fitness, 2.0353E-04 mean fitness, 3.75E-06 STD measure and using the shortest possible time (281 s) to complete the 100-runs iteration process. FSSO displayed the overall lowest performance with a global worst fitness value of 7.2618E-01, mean fitness value of 2.0776E-02, STD value of 7.5015E-02 and 1370.45 s simulation run-time.

Lastly, for Table 14, using 7-parameter PWP cells, results show that IJSO exhibited the best performance with a value of 2.4268E-03 as the global-best fitness value, 2.4273E-03 worst fitness, 2.4268E-03 mean fitness, 4.96E-08 STD measure and using the shortest possible time (227.29 s) to complete the simulation process. Also, FSSO displayed the lowest performance with a global worst fitness value of 4.1545E-01, 6.2715E-02 STD measure and 755.733 s simulation run-time.

Case study 2(c) results

Similar to cases 2(a) and 2(b), Tables 16, 17, and 18 present the output performances for the proposed IJSO compared with HHO, FSSO, and MFO algorithm. From the tabulated results, IJSO outperformed the other existing algorithms used for comparison. That is, for Table 16, IJSO achieved the best fitness with a RMSE value of 9.853E-04 and using the shortest possible run-time of 352.39 s while HHO under-performed with a recorded RMSE value of 2.578E-04.

For Table 17, using 9-parameters PVM, the proposed IJSO achieved the best performance with an RMSE value of 1.450E-04, worst RMSE of 2.284E-04, average RMSE of 1.461E-04, standard deviation of 8.560E-06, and a simulation run-time of 406.94 s.

For Table 18, using 9-parameters PWP panel, the proposed IJSO also attained the best performance with a RMSE value of 2.427E-03, worst RMSE of 2.427E-03, average RMSE of 2.427E-03, standard deviation of 5.093E-11, and a simulation run-time of 354.84 s.

Table 19; Figs. 30, 31, 32 present the tabulated contingency Table and the corresponding I-V curves using three-diode cells simulated using RTC cell, PVM cell and PWP cells. From the Figures, IJSO outperformed in all cases as the predicted I – V curve using worst IJSO RMSE values exhibited the lowest absolute errors between measured current and calculated errors for the RTC cell, PVM cell, and PWP cells modelled using 9-parameter topology.

Case Study 3 results

The two photovoltaic array configurations experimented under standard test conditions (STC) are discussed and analyzed below.

Case study 3a results

For case study 3a, Table 20; Fig. 33 present results attained for Case study 3a with the anticipated optimization techniques (IJSO, HHO, FFSO, and MFO) simulated with MATLAB/Simulink environment for 2.3 s to control the output power from the arrayed panels with these algorithms. From the outcomes, IJSO outshine the other algorithms as the algorithm (IJSO) precisely located the global maxima with a peak power of 995.6 Watts and within the shortest possible time (0.2081 s), average power of 973.9 W, 993.9 W median power, and a root mean square (RMS) power of 978.4 W. In contrast, MFO under-performed with an average power of 906 Watts and an RMS power of 918 Watts, followed by FSSO that took the lengthiest time (2.1999 s) to locate a global maximum power of 992.3 Watts, and with an average power of 944.8 Watts, median power of 988.2 Watts, and 952.3 Watts RMS power.

Case study 3b results

The results analysis for the second, uniformly-isolated 5-series connected 1STH-215P PV system are presented in Table 21; Fig. 34. Similarly, IJSO demonstrated the absolute-best improvement with a peak power of 1067 W achieved within the shortest feasible time of 0.2903 s, along with an average power of 1060 W, and RMS power of 1062 W at a duty cycle position of 0.3888. In opposition, the FSSO technique demonstrated poor results, with its 1066 Watts peak power tracked at 3.6184 s, along with a mean power of 1034 W, mid-point power of 1065 W and 1038 W RMS power.

Case study 4

The partial shading condition outcomes using same-cell and different-cell materials in case study 4 are presented below.

Case study 4a results

A breakdown of the results obtained for Case Study 4(a) is shown in Table 22 and Figure Fig. 35. IJSO proved to be the best algorithm with a GMPPT power of 637.7 Watts, and a mean, median, and RMS power of 623.3 W, 637.2 W, and 627.4 W respectively.

In addition, the fast exploitation with IJSO can be observed from the graph shown below as IJSO located an accurate GMPPT within 0.18 s, whereas the other algorithms only converged after 0.9 s. Also, FSSO demonstrated the worst performance with a mean, median, and RMS power of 607.8 W, 634.4 W, and 611.4 W correspondingly and with its maximum power point located after 2.2 s run-time.

Case study 4b results

For case study 4(b), Table 23; Fig. 36 present the simulation results for five series-connected ET-P654200WW polycrystalline panels simulated for 2 s. From the tabulated results, IJSO displayed the overall best effectiveness with a peak power of 667 W at 0.1608 s and a mean, median and RMS power of 660.7 W, 660.4 W, and 661.1 W respectively. Whereas FSSO displayed the overall least effectiveness with 666 Watts peak power tracked at 1.90 simulation time and with an average power of 617.5 W, 656.7 W mid-point power, and 625.8 Watts RMS power.

Case study 4(c) results

Results for the PV array system modelled using different cell materials are shown in Table 24; Fig. 37. Likewise, IJSO demonstrated the finest performance with an ample power of 655.6 W, 646.9 W mean power, and RMS power of 648.9 W. In contrast, FSSO showed the least performance with a maximum power of 654 W and RMS power of 632.6 W at 0.344 global-best (duty cycle) position.

Furthermore, from Fig. 37 graphical results, IJSO exhibited the quickest exploitation convergence, as the GMPP was tracked after running the simulation for 0.2103 s while FSSO algorithm particles could not converge for the 2.5 seconds’ experimental time.

Case study 5 results

For case study 5, tabulated results collected running the experiment for 2.2 s are displayed in Table 25. From the Table, three of the algorithms (IJSO, HHO, and FSSO) were successful in locating the global maxima but at different time intervals. Also, IJSO proved to be the most efficient with a RMS power of 83.84 Watts, followed by HHO algorithm. Similarly, FSSO demonstrated the least efficiency with RMS power of 82.31 W.

Figure 38 displays the graphical outcomes for case study 4(c). The fast convergence of IJSO can be observed as it took one-twentieth (0.2103 s) of the total simulation time (4 s) for the algorithm to track the GMPPT whereas MFO and FSSO took longer time (3.2804 s) and 2.4532 s to locate their global maximum power point respectively.

Case study 6 results

Table 26 presents tabulated results for the average power, estimated daily energy and the savings that can be achieved using 5 series-connected solar panels and a MPPT controller monitored using IJSO, HHO, MFO and FSSO algorithm. From the Table, it can be proven that IJSO yielded the highest savings as R10.77 can be earned by household users and R5.15 by business users. On the other hand, MFO yielded the least expected results with an estimated daily savings of 4.28 for home users and R2.08 for business users.

Also, from Fig. 39, the issue of getting trapped at local optima was experienced by these three existing algorithms (FSSO, HHO, and MFO) around 9.45 AM for MFO, 9:05 AM for FSSO, and around 10:30 AM for HHO respectively. Whereas, from steady power-supply state, the proposed IJSO was able to respond rapidly to sudden changes in GHI and power by re-initializing and re-evaluating new duty cycles that will allow optimum power flow from the inter-connected PV system used for research.

Similarly, Table 27 presents an estimated daily savings during summer using the considered optimization techniques. From the Table, the IJSO algorithm had the best performance with an average power of 570.2 W, RMS power of 644.9 W, R21.88 electricity income for home users and R10.47 for business users. MFO algorithm experienced the lowest performance with an average power of 133.6 W, 140.7 W RMS power, R5.13 savable electricity income for home users and R2.45 for business users.

Also, from Fig. 40, problems of getting trapped at local optima were observed around 7:35 AM using MFO, 6:30 AM using FSSO, and 8:25 AM using HHO.

Conclusion

This paper demonstrated the effectiveness of the improved Jellyfish Search Optimization (IJSO) technique, developed through the hybrid combination of the original Jellyfish Search Optimization (JSO) algorithm and the Lévy flight movement from the Cuckoo Search (CS) algorithm, in solving both minimization and maximization problems with high accuracy. The IJSO algorithm was tested against three recent metaheuristic techniques: Harris Hawk Optimization, Mayfly Optimization, and Flying Squirrel Search Optimization, across six case studies. These case studies included benchmark tests on six well-known objective functions, parameter extraction from photovoltaic (PV) cells, and power optimization in PV systems under different environmental conditions. The results consistently showed that IJSO achieved the best overall performance, proving its robustness and suitability for solving both minima and maxima objective-function problems, including solar cell parameter extraction and global peak power point tracking in PV systems under varying weather conditions.

Future work

Future research should explore incorporating other algorithms, such as the Jaya algorithm and Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization (TLBO) and applying advanced mapping methods like the Zaslavskii and Kaplan-Yorke maps to further enhance the algorithm’s effectiveness in solving multi-objective optimization problems. Additionally, hardware implementation of the proposed algorithm is recommended for future studies to assess its practical viability.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable re-quest.

References

Claudio, G., Bissan, G. & Joe, N. S. Optimization problems for machine learning: a survey. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 290(3), 807–828 (2021).

Shiliang, S., Zehui, C., Han, Z. & Jing, Z. A survey of optimization methods from a machine learning perspective, eprint arXiv:1906.06821, pp. 1–30, 23 October 2019.

Farayola, A., Hasan, A. & Ali, A. Optimization of PV systems using data mining and regression learner MPPT techniques. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 10(3), 1080–1089 (2018).

Bansal, R., Singh, J. & Kaur, R. Machine learning and its applications: a review. J. Appl. Sci. Comput. 6(6), 1392–1398 (2020).

Gaviria, J. F., Narvaez, G., Guillen, C., Giraldo, L. & Bressan, M. Machine learning in photovoltaic systems: A review 196, 298–318, (2022).

Farayola, A. M., Hasan, A. N. & Ali, A. Efficient photovoltaic MPPT system using coarse gaussian support vector machine and artificial neural network techniques. Int. J. Innov. Comput. Inf. Control 14(1), 323–339 (2018).

Huang, S. et al. Applications of support Vector Machine (SVM) learning in cancer genomics. Cancer Genomics Proteom. 15(1), 41–51 (2018).

Cavazzuti, M. Optimization methods: From theory to design (Springer, 2013).

Li, D. et al. Recent photovoltaic cell parameter identification approaches: a critical note. Front. Energy Res. 10, 1–5 (2022).

Elia, H., Veronika, L., Martin, S., Samuel, K. & Christian, K. A literature review on optimization techniques for adaptation planning in adaptive systems: state of the art and research directions. Inf. Softw. Technol. 149 (2022).

Farayola, A. M., Sun, Y. & Ali, A. Global maximum power point tracking and cell parameter extraction in photovoltaic systems using improved firefly algorithm. Energy Rep. 8(8), 162–186 (2022).

Sairam, A. B., Yogesh, S., Manoj, K., Sanju, R. & Singh, V. N. Investigation of different configurations in GeSe solar cells for their performance improvement. J. Nanomater. 2023, 1–14 (2023).

Mostafa, A., Ibrahim, H., Ralph, K., Jose, R. & Mohamed, A. An improved photovoltaic maximum power point tracking technique-based model predictive control for fast atmospheric conditions. Alex. Eng. J. 63(15), 613–624 (2023).

Flores, E., Ortiz, A., Macias, I. & Molina, A. Experimental validation of an enhanced MPPT algorithm and an optimal DC–DC converter design powered by metaheuristic optimization for PV systems. Energies 15(21), 1–35 (2022).

Spertino, F. et al. An innovative technique for energy assessment of a highly efficient photovoltaic module. Solar 2(2), 321–333 (2022).

Farayola, A., Hasan, A. & Ali, A. Implementation of modified incremental conductance and fuzzy logic MPPT techniques using MCUK converter under various environmental conditions. Appl. Solar Energy 53, 173–184 (2017).

Kapilan, N., Nithin, K. & Chiranth, K. Challenges and opportunities in solar photovoltaic system. Mater. Today Proc. 62(6), 3538–3543 (2022).

Farayola, A., Hasan, A. & Ali, A. Use of MPPT techniques to reduce the energy pay-back time in PV systems, in 9th International Renewable Energy Congress (IREC), Hammamet, Tunisia, 1–6. (2018).

Rashid, M. & Akubo, S. A. Solar energy for sustainability in Africa: the challenges of socio-economic factors and technical complexities. Int. J. Energy Res. 46(12), 16336–16354.

Pakkiraiah, B. & Durga, S. G. Research survey on various MPPT performance issues to improve the solar PV system efficiency. J. Solar Energy 2016(6), 1–20 (2016).

Farayola, A., Hasan, A. & Ali, A. Comparison of modified incremental conductance and fuzzy logic MPPT algorithm using modified CUK converter, in 2017 8th International Renewable Energy Congress (IREC), Amman, Jordan, 1–6. (2017).

Roni, H., Sohel, R., Hassan, M. & Pota, H. Recent trends in bio-inspired meta-heuristic optimization techniques in control applications for electrical systems: a review. Int. J. Dyn. Control 10(2), 1–13 (2022).

Bollipo, R. B., Suresh, M. & Praveen Kumar, B. Critical review on PV MPPT techniques: classical, intelligent and optimisation. IET Renew. Power Gener. 14(9), 1433–1452 (2020).

Farayola, A. H. A. & Ali, A. T. B. Distributive MPPT approach using ANFIS and perturb&observe techniques under uniform and partial shading conditions, in Artificial Intelligence and Evolutionary Computations in Engineering Systems: Proceedings of ICAIECES 2017, Springer, Singapore, pp. 27–37. (2017).

Al-Ezzi, A. S., Mohamed, N. & Ansari, M. Photovoltaic solar cells: a review. Appl. Syst. Innov. 5(4), 1–17 (2022).

Kumar, V. N. & Singh, S. Solar photovoltaic modeling and simulation: As a renewable energy solution. Energy Rep. 4, 701–712 (2018).

Farayola, A. M., Yanxia, S. & Ali, A. Comparative study of optimization techniques based on solar cell parameter extraction, in 61st International Scientific Conference on Information Technology and Management Science of Riga Technical University (ITMS), Riga, Latvia, 2020, pp. 1–6. (2020).

Meng, X., Ji, Y. & Wang, J. Iterative parameter estimation for photovoltaic cell models by using the hierarchical principle. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 20, 2583–2593 (2022).

Ćalasan, M., Shady, H., Abdel, A. & Zobaa, A. F. A new approach for parameters estimation of double and triple diode models of photovoltaic cells based on iterative Lambert W function. Sol. Energy 218, 392–412 (2021).

Farayola, A. & Sun, Y. A. A. Optimization of PV systems using linear interactions regression MPPT techniques, in 2018 IEEE PES/IAS PowerAfrica, Cape Town, pp. 545–560. (2018).

Farayola, A. & Sun, Y. A. A. Optimization of PV systems using ANN-PSO configuration technique under different weather conditions, in 7th International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications (ICRERA), Paris, France, 2018, pp. 1363–1368. (2018).

Ruschel, C. S., Fabiano, P. G. & Arno, K. Experimental analysis of the single diode model parameters dependence on irradiance and temperature. Sol. Energy 217, 134–144 (2021).

Galicia, F. M., Pascual, M. T., Quintero, P. R. & Moreno, M. M. Solar cell parameter extraction method from illumination and dark I-V characteristics. Nanomaterials (Basel) 12, 1–15 (2022).

Singla, M. K. & Nijhawan, P. Triple diode parameter estimation of solar PV cell using hybrid algorithm. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 1–24 (2021).

Baig, M. Q., Khan, H. A. & Ahsan, S. M. Evaluation of solar module equivalent models under real operating conditions—A review. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 12(012701), 1–13 (2020).

Farayola, A., Sun, Y. & Ali, A. 8-parameter extraction in Photovoltaic cell using Firefly optimization technique, in 2021 IEEE Electrical Power and Energy Conference (EPEC), Toronto, Canada, pp. 184–189. (2021).

Elazab, O., Hasanien, H., Alsaidan, I., Abdelaziz, A. & Muyeen, S. Parameter estimation of three diode photovoltaic model using Grasshopper optimization algorithm. Energies 13(497), 1–15 (2020).

Konstantinos, Z. & Stelios, T. A mayfly optimization algorithm. Comput. Ind. Eng. 145(106559), 1–23 (2020).

Gao, Z. M., Juan, Z., Li, S. R. & Hu, Y. R. The improved mayfly optimization algorithm. J. Phys. 1684, 1–7 (2020).

Gao, Z., Zhao, J., Li, S. & Hu, Y. The improved mayfly optimization algorithm. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1684(012077), 1–7 (2020).

Guo, L., Xu, C., Yu, T. & Wumaier, T. An improved Mayfly optimization algorithm based on median position and its application in the optimization of PID parameters of Hydro-turbine Governor. IEEE Access 10, 36335–36349 (2022).

Yan, Z., Yan, J., Wu, Y. & Zhang, C. An improved hybrid mayfly algorithm for global optimization, J. Supercomput. 2022(6), 5878–5919 (2022).

Ayappan, G., & Anila, S. Mayfly Optimization with Deep Belief Network-Based Automated COVID-19 Cough Classification Using Biological Audio Signals. Cybernetics Syst. 54(6), 767–786 (2023).

He, X. et al. MPPT control based on improved mayfly optimization algorithm under complex shading conditions. Int. J. Emerg. Electr. Power Syst. 22(6), 661–674 (2021).

Chen, N. et al. Mayfly optimization algorithm–based PV cell triple-diode model parameter identification. Front. Energy Res. 10, 1–10 (2021).

Yi, L., Shi, H., Liu, J.et al., Dynamic Multi-peak MPPT for Photovoltaic Power Generation Under Local Shadows Based on Improved Mayfly Optimization. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 17, 39–50 (2022).

Shixun, M., Qintao, Y., Kunping, J., Xiaofeng, M. & Gengyu, S. An improved MPPT method for photovoltaic systems based on mayfly optimization algorithm. Energy Rep. 8(5), 141–150 (2022).

Tripathy, B. K. et al. Harris Hawk optimization: A survey on variants and applications. Hindawi Comput. Intell. Neurosci., 1–20 (2022).

Ali Asghar, H. et al. Harris hawks optimization: Algorithm and applications. Future Gen. Comput. Syst. 97, 849–872 (2019).

Alabool, H., Alarabiat, D., Abualigah, L. & Heidari, A. Harris hawks optimization: a comprehensive review of recent variants and applications. Neural Comput. Appl. 33, 8939–8980 (2021).

Gezici, H. & Livatyalı, H. Chaotic Harris hawks optimization algorithm. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 9(1), 216–245 (2025).

Sihwail, R., Omar, K., Zainol, A. & Tubishat, M. Improved Harris Hawks optimization using elite opposition-based learning and novel search mechanism for feature selection. IEEE Access. 8, 121127–121145 (2020).

Hafeez, M. A. et al. A novel hybrid MPPT technique based on Harris Hawk optimization (HHO) and perturb and observer (P&O) under partial and complex partial shading conditions. Energies 15, 1–18 (2022).

Gali, V., Babu, B. C., Mutluri, B., Gupta, M. & Gupta, S. Experimental investigation of Harris Hawk optimization-based maximum power point tracking algorithm for photovoltaic system under partial shading conditions. Opti. Control Appl. Methods 44(2), 577–560 (2023).

Majad, M., Adeel Feroz, M. & Qiang, L. Harris hawk optimization-based MPPT control for PV systems under partial shading conditions. J. Clean. Prod. 274, 1–19 (2020).

Mohit, J., Vijander, S. & Asha, R. A novel nature-inspired algorithm for optimization: Squirrel search algorithm. Swarm Evol. Comput. 44, 148–175 (2019).

Yanjiao, W. & Tianlin, D. An improved Squirrel search algorithm for global function optimization. Algorithms 12(4), 1–29 (2019).

Gholamreza, A., Farid, M., Naser, S. & Mohsen, R. Flying Squirrel Optimizer (FSO): a novel SI-based optimization algorithm for engineering problems. Iran. J. Optim. 11(2), 177–205 (2019).

Nagendra, S., Krishna Kumar, G., Jain, S., Niraj Kumar, D. & Pallavee, B. A flying Squirrel search optimization for MPPT under partial shaded photovoltaic system. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 9(4), 4963–4978 (2020).

Aripriharta, A. et al. The performance of a new heuristic approach for tracking maximum power of PV systems. Appl. Comput. Intell. Soft Comput. 1–13 (2022).

Zheng, T., & Luo, W. An Improved Squirrel Search Algorithm for Optimization. Complexity 2019, 6291968, (2019).

Vincenzo, F., Aldo, O. & Alessandra, D. G. Assessment of the usability and accuracy of the simplified one-diode models for Photovoltaic modules. Energies 9(12), 1–41 (2015).

Nagendra, S., Gupta, K., Jain, S., Dewangan, N. & Bhatnagar, P. A flying Squirrel search optimization for MPPT under partial shaded photovoltaic system. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 9(4), 4963–4978 (2020).

Chou, J. S. & Truong, D. A novel metaheuristic optimizer inspired by behavior of jellyfish in ocean. Appl. Math. Comput. 389, 1–47, (2021).

Chou, J. & Asmare, M. Recent advances in use of bio-inspired jellyfish search algorithm for solving optimization problems. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–23 (2022).

Khare, A., Kakandikar, G. & Kulkarni, O. An insight review on jellyfish optimization algorithm and its application in engineering. Rev. Comput. Eng. Stud. 9(1), 31–40 (2021).

Farhat, M., Kamel, S., Atallah, A. M. & Khan, B. Optimal power flow solution based on Jellyfish search optimization considering uncertainty of renewable energy sources. IEEE Access. 9, 100911–100933 (2021).

Chou, J., Tjandrakusuma, S. & Liu, C. Jellyfish search-optimized deep learning for compressive strength prediction in images of ready-mixed concrete. Hindawi Comput. Intelli. Neurosci. 2022(9359848), 1–26 (2022).

Mohamed, A., Mohamed, R., Chakrabortty, R., Ryan, M. & El-Fergany, A. An improved artificial Jellyfish search optimizer for parameter identification of Photovoltaic models. Energies 14(1867), 1–33 (2021).

Alam, A. et al. Jellyfish search optimization algorithm for MPP tracking of PV system. Sustainability 13(21), 1–20 (2021).

Huang, R. & Lin, Y. A maximum power point tracking strategy for Photovoltaic system based on improved artificial Jellyfish search optimizer, in 3rd International Academic Exchange Conference on Science and Technology Innovation (IAECST), Guangzhou, pp.1918–1922. (2021).

Zhao, J. & Gao, Z. M. The fully informed mayfly optimization algorithm, in 2020 International Conference on Big Data and Artificial Intelligence and Software Engineering (ICBASE), Bangkok, Thailand, pp. 450–453. (2020).

Fortes, E. V. et al. Mayfly optimization algorithm applied to the design of PSS and SSSC-POD controllers for damping low-frequency oscillations in power systems. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst.2022, 1–23 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AF, YS, AA and BK wrote the main manuscript text. AF, YS, AA and BK prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Farayola, A., Sun, Y., Ali, A. et al. Application of improved Jellyfish search algorithm for 9-parameters cell extraction and GMPPT in PV systems. Sci Rep 14, 24602 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75619-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75619-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Cauchy distribution optimizer for photovoltaic model parameter extraction and numerical optimization

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Boosting Walrus Optimizer Algorithm based on ranking-based update mechanism for parameters identification of photovoltaic cell models

Electrical Engineering (2025)

-

Robust Opposition-Based Jellyfish Search Algorithms for Large-Scale and Bound-Constrained Optimization

SN Computer Science (2025)