Abstract

Ceftriaxone stands as a cornerstone in global antibiotic therapy owing to its potent antibacterial activity, broad spectrum coverage, and low toxicity. Nevertheless, its efficacy is impeded by widespread inappropriate prescribing and utilization practices, significantly contributing to bacterial resistance. The aim of this study is to determine the overall national pooled prevalence of inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization and its predictor factors in Ethiopia. A systematic search was conducted across multiple databases including, PubMed, Science Direct, Hinari, Global Index Medicus, Scopus, Embase, and a search engine, Google Scholar, to identify relevant literatures that meet the research question, from March 20 to 30, 2024. This meta-analysis, which was conducted in Ethiopia by incorporating 17 full-text articles, unveiled a national pooled inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization of 55.24% (95% CI, 42.17%, 68.30%) with a substantial heterogeneity index (I2 = 99.24%, p value < 0.001). The review has also identified predictive factors for the inappropriate use of ceftriaxone: empiric therapy (AOR 21.43, 95% CI; 9.26–49.59); multiple medication co-prescription (AOR: 4.12, 95% CI; 1.62–8.05). Emergency ward (AOR: 4.22, 95% CI; 1.8-12.24), surgery ward (AOR: 2.6, 95% CI; 1.44–7.82) compared to medical ward, prophylactic use (AOR: 500, 95% CI; 41.7–1000), longer hospital stay-8-14 Days; (AOR: 0.167, 95% CI; 0.09–0.29), > 14 days; (AOR: 0.18, 95% CI; 0.1–0.32). The study reveals a high national pooled prevalence of inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization, standing at 55.24%, highlighting a significant hazard in the use of this antibiotic. This could be attributed to instances of overuse, misuse or prescription practices that deviates from established guidelines. This eminent challenge can lead to the development of antibiotic resistance, increased healthcare costs, adverse drug reactions, and treatment failures, necessitating multifaceted approach such as improved antibiotic stewardship, better adherence to guidelines, and enhanced clinician education on appropriate antibiotic use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Irrational use of medication presents a significant global challenge, particularly in developing nations. Assessing the pattern of drug utilization plays a pivotal role in pinpointing gaps in medicine utilization and enables the implementation of targeted strategies for promoting rational drug use1. Rational use of medicines is the process by which patients receive medications tailored to their clinical needs, in doses that meet their requirements, for a sufficient duration of time, and at the lowest cost2. This approach minimizes the incidence of adverse drug events while maximizing the benefits that can be gained from the optimal use of medications. Furthermore, the rational use of drugs can also lead to efficient allocation of scarce healthcare resources3.

Rational drug use (RDU), is the process of appropriate prescribing, dispensing, and patient use of drugs for diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of diseases4. Conversely, irrational use of medicines arises when one or more of the above-mentioned conditions are not met5. The indiscriminate use of medications can lead to treatment failures and adverse drug events. Particularly concerning is the misuse of antibiotics, which exacerbates drug resistance, limiting available therapeutic options and rendering alternative treatments unaffordable for many. Consequently, patient confidence in the healthcare system wanes3.

Antibiotics are among the most commonly prescribed medication classes and essential parts of modern medicine, serving as key tools both for the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases. However, the current trend of their misuse can lead to significant morbidity, pronounced healthcare costs, and predominantly the emergence of antimicrobial resistance6,7.

Ceftriaxone, a third-generation cephalosporin, serves as a pivotal element in global antibiotic therapy. It’s extensively prescribed and empirically used for its high antibacterial potency, wide spectrum of activity, and low potential for toxicity. However, despite its pivotal role, there exists a concerning prevalence of inappropriate prescription and usage of ceftriaxone in both developing and developed nations, contributing to bacterial resistance8,9,10.

According to the WHO report, inappropriate prescribing and dispensing of medicines accounts for over 50% of all medicines globally, and approximately 50% of patients fail to adhere to their prescribed medication regimen11. Out of many antibiotics, ceftriaxone is a very commonly used and at the same time commonly misused antibiotic12. Hence, the first logical step to assess the misuse of antimicrobial agents is to evaluate the suitability of its usage. However, relying solely on data gathered from individual hospitals offers limited insights for effective policy-making13. As a result, we conducted a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis to comprehensively examine the appropriateness of ceftriaxone utilization. Therefore, the current systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to determine the overall national pooled prevalence of inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization and its predictor factors in Ethiopia.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This systematic review and meta-analysis was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol14 (Supplementary File S1). There was no registered protocol for this systematic review and Meta-Analysis.

Search strategy

A systematic search was conducted across multiple databases including, PubMed, Science Direct, Hinari, Global Index Medicus, Scopus, Embase, and a search engine, Google Scholar, to identify relevant literatures that meet the research question at hand. In addition, the reference lists of all eligible articles were searched manually to retrieve additional relevant articles. The search was carried out from March 20 to April 10, 2024, using specific key terms such as “(((Ceftriaxone [MeSH Terms]) OR (Ceftriaxone use)) AND ((Drug utilization [MeSH Terms]) OR (Drug use))) AND (Ethiopia [MeSH Terms]). Various search strategies were incorporated including truncation (*), Boolean operators (‘OR’ and ‘AND’), and phrase searching (“…”). Additionally, we employed synonyms to expand the scope of the search, and search terms from each database were saved, and exported as detailed in (Supplementary File S1).

Data selection

All searched articles were uploaded to EndNote software to remove any duplicates. Following this, studies were selected based on the eligibility criteria by two independent investigators. The two researchers, screened the titles, abstracts, and the full text of all retrieved references to identify potentially eligible studies based on the inclusion criteria. Seventeen eligible studies were identified from a total of 988 search results. Then data extraction from the 17 studies was independently done by the two investigators and any differences between the reviewers were resolved through discussion.

Data extraction and analysis

A pre-prepared EXCEL data extraction sheet was employed to gather data from the eligible studies that consisted name of the primary author, year of publication, region of the country, study setting, study design, sampling technique, sample size, and proportion of inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization. In addition, the extraction sheet encompasses factors associated with inappropriate ceftriaxone usage and presents adjusted odds ratio along with their corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) derived from the selected studies.

After this, data was exported to STATA version 17 statistical software for meta-analysis. Pooled prevalence was investigated using a random-effects model with the Dersimonian-Laird method15. Finally, the results were presented through textual descriptions, tables, and various graphical plots. A forest plot was used to estimate pooled prevalence along with a 95% CI to provide a visual summary of the data. To evaluate heterogeneity among included studies, the I-squared (I2) index, with was employed16,17. Furthermore, to explore sources of heterogeneity among the studies, Meta-regression was employed. Subsequently, subgroup analyses were performed by region of the country and study setting, to explore the impact of geography and institutional hierarchy on inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization. Additionally, sampling technique was evaluated to understand ceftriaxone utilization across different sampling methods. Funnel plots was employed to visually examine publication bias, supplemented by Begg’s and Egger’s regression tests for more objective assessment. These tests were chosen due to their heightened sensitivity in detecting publication bias compared to other methods17,18.

Risk of bias (quality) assessment

Methodological Quality of each included study was assessed by two independent Authors, (CT & DGD). The studies underwent critical appraisal for quality using the Newcastle Ottawa appraisal tool for nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses, which rates study quality out of 10 points19. The two authors independently scored the articles and any disagreement in scoring was solved through discussion and involving a third author. Ultimately, the study quality scores were derived by summing assigned values. Studies with a minimum score of 6 were selected for inclusion in the final analysis20.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

This review included all types of studies, both observational and interventional, that focused on ceftriaxone prescribing pattern or rational drug use in Ethiopia and published in English-language. This review puts no restriction to the study period, articles accessed within the search period, from March 20 to April 10, 2024, were included.

Exclusion criteria

Articles lacking abstracts or full texts, anonymous reports, and editorials. Studies that did not explicitly explain the outcome variable or lacking clear reporting of outcome variable were excluded.

Outcome measurement

The primary outcome of this study was assessing inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization among patients prescribed with this medication. It was determined as the proportion of patients who were using this medication inappropriately, calculated against the total number of patients who had received the drug. Inappropriateness was defined by a set of criteria aligned with the Ethiopian treatment guidelines, encompassing four key parameters: indication for use, dosage, frequency of administration, and duration of therapy. Appropriateness was declared when the use was in line with this guideline21. The secondary outcome was to determine predictors of inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization.

Result

Search results

As detailed in the flowchart below, (Fig. 1), from a manual and database searches, a total of 988 articles were identified. After an initial and exhaustive screening process for duplicates, one-hundred-forty-nine were identified and eliminated leaving 839 refined collections. Of these, 818 records were deemed irrelevant to the focus of this review based on titles and abstracts, and thus were excluded from further considerations. Subsequently, the remaining 21 full articles were prepared for retrieval to be thoroughly assessed for eligibility based on the inclusion criteria. Four studies were excluded from our analysis for various reasons, one study failed to define and report the outcome variable at all22, another lacked full-text availability and could not be retrieved for further analysis23. The remaining two studies did not contain the outcome of interest24,25. Ultimately, 17 full articles8,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis.

Characteristics of the studies included

In this meta-analysis, we incorporated 17 studies that evaluated ceftriaxone drug use pattern and published in the year between 2012 and 2023. The key findings are illustrated in Table 1. The sample sizes of these studies varied from 127 to 800, with a cumulative sample size of 6130. The populations studied primarily consisted of the general population encompassing a diverse age range, from newborns (1 day) to older adults (over 65 years). When classified geographically, two of the studies were conducted in Tigray Regional state, six in Addis Ababa, four in Amhara, one in South Western part of Ethiopia and the remaining four in Oromia. All the included studies employed a cross-sectional study design. In terms of sampling technique, nine studies utilized systematic random sampling, four of them simple random sampling and the remaining four were conducted on the entire patient population (Census). In terms of type of therapy, the proportion of empiric therapy varied significantly among studies, with rates as high as 98.4% (e.g., in the Federal Police Referral Hospital study) and as low as 59.7% in Ras-Desta Memorial General Hospital. This suggests a reliance on clinical expertise and experience in initiating treatment before confirming a diagnosis.

Risk of bias assessment

The comprehensive assessment conducted in this systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that all studies, evaluated using the rigorous Newcastle-Ottawa Scale quality appraisal criteria, demonstrated negligible risk. Consequently, all studies were deemed suitable for inclusion in our review and subsequent analysis.

The pooled prevalence of inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization

Using the random effect model, the national pooled prevalence of inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization turned out to be 55.24% (95% CI, 42.17%, 68.30%) with the heterogeneity index (I2 = 99.24%, p value < 0.001), displaying marked heterogeneity among the studies. The prevalence of inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization for the individual studies ranged from 8%30 to 87.9%8. Weights assigned to individual studies in a forest plot reflect their respective contributions to the overall pooled outcome42. The current study revealed a very close distribution of weight across the studies, ranging from 5.72% to 5.92% (Fig. 2).

Sensitivity analysis

In meta-analysis, sensitivity test reveal how much the overall findings are influenced by each individual studies included in the meta-analysis. It evaluates the robustness of the observed outcomes to the assumptions made in performing the analysis. This helps identify whether any single study has a disproportionate effect on the pooled estimate43,44. Consequently, the results from a random-effects model in the present study indicated that no single study influenced the overall pooled level of inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization. (Fig. 3).

Subgroup analysis of inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization

In response to the observed heterogeneity among the studies, we conducted meta-regression to investigate potential predictors of variability and gain a comprehensive understanding of the overall effect. Subsequently, regression analysis was performed by region of the country, study setting and sampling technique. However, none of these factors showed a statistical significant association. Nevertheless, we proceeded with a subgroup analysis encompassing all three of the above factors. Region and study setting were specifically included in our analysis to determine the pooled prevalence of inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization across geographical areas and different institutions, respectively. Meanwhile, the incorporation of sampling technique was to assess its distribution across various sampling methods (Table 2).

The pooled prevalence of inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization exhibited minimal variability among the five states included, the highest being 60.20(95% CI 41.77–78.64) in Addis Ababa and the lowest, 51.06(95% CI 12.37–89.75) in Amhara regional state. On the other hand, a significant variability was observed in terms of study setting ranging between 43.86 (95% CI 30.73–56.99), in General Hospitals and 87.9% (95% CI 84.29–91.55) in Specialized Hospital. Meanwhile, a more consistent distribution was noticed on the different sampling techniques employed, falling within 54.31(95% CI 19.10, 89.52) and 55.76 (95% CI 43.78, 67.74) for simple random sampling and Systematic random sampling respectively.

Pooled predictor of inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization

As depicted in Fig. 4, out of the reviewed articles, three distinct studies outlined the impact of empiric therapy on inappropriate ceftriaxone usage. Notably, patients that received empiric treatment exhibited a significantly higher likelihood, 21.43 times more (AOR, 95% CI (9.26, 49.59))—of improper medication intake compared to those prescribed with definitive therapy.

Factors associated inappropriate utilization of ceftriaxone

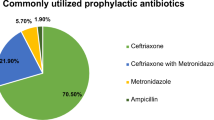

Among the studies examined, a study conducted by Ayele et al. uncovered a significant association between multiple medication co-prescription and an increased likelihood of inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization, with AOR 4.12 (95% CI 1.62, 8.05). A higher likelihood of non-compliance with guidelines was also noticed among patients admitted to Emergency and surgery departments with AOR 4.22 (95% CI 1.8, 12.24) and AOR 2.6 (95% CI 1.44, 7.82) respectively, compared to those in medical ward, in a study conducted by Muhammed et al.,. This result was further supported in a research carried out by Shimels et al., where, patients admitted to Gynecology and Obstetrics, Medical and Pediatrics departments showed a decreased propensity for inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization by 69%, 67.6% and 80.8% respectively (Table 3). Meanwhile, prophylactic use demonstrated a 500-fold increased likelihood for inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization compared to specific therapy (95% CI, 41.7, 1000).

In contrast, longer hospital stays of, 8–14 days and > 14 days displayed 83.3% and 78% lesser likelihood, respectively, of inappropriate ceftriaxone use pattern when compared to stays of 0–7 days. Additionally, the provision of free health service was linked to an 87.1% lesser likelihood of compliance to guidelines when compared with charged patients.

Meta-analysis

Publication bias

A funnel plot is a scatter plot frequently utilized in meta-analyses to unveil publication bias through visual detection. As depicted in Fig. 5, the plot displays asymmetry in the distribution of the included studies. However, when evaluated using more objective measures, such as Egger’s and Begg’s test, the results were statistically insignificant (p = 0.9676 and p = 0.9016, respectively), suggesting the absence of publication bias.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to generate the national pooled estimate of inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization pattern in Ethiopia, along with identifying key predictor factors associated with its misuse. Making our primary focus, ceftriaxone, owing to its frequent misuse due to higher rate of utilization45, this review provides targeted insights into its prescribing practices in the Ethiopian context. This helps promote rational antibiotic use and combat antimicrobial resistance which usually happens due to overuse of antimicrobials and has become a major public health concern to health institutions and the global society as a whole46.

In the present study, our analysis revealed a pooled prevalence of inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization at 55.24% (95% CI, 42.17%, 68.30%). This finding indicates that a little over half of the studied patients did not receive appropriate treatment regimen involving ceftriaxone, posing a serious challenge to effective therapy, and warranting immediate attention. This emphasizes the need for targeted interventions to address this pressing issue. Targeted interventions are essential to improve prescribing practices, as inappropriate use of antibiotics has been strongly linked to the emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrobial resistance, largely stemming from the misuse and over-prescription of antibiotics, presents a formidable global crisis that demands a multifaceted approach. This approach should include promoting judicious antibiotic usage through education and guidelines for healthcare providers, enhancing surveillance of antimicrobial resistance patterns, and enforcing stringent regulations on antibiotic utilization within the healthcare system and other sectors9,47,48,49.

Ceftriaxone misuse is a widespread and highly prevalent issue in healthcare facilities globally, though comprehensive meta-analyses on this topic are limited. A study conducted by Durham et al.,. in Alabama and west Georgia found a 53% inappropriate ceftriaxone use, closely aligning with our findings50. Similarly, this concerning trend extends to the East African region with reported rates of 32.1% in Uganda45, , 62.4% in Eritrea46, , and as high as 68.9% in terms of frequency in Sudan51.

The present study has also identified factors that contributed to the inappropriate usage of ceftriaxone, that deviate from established guidelines. Accordingly, treatment modalities, particularly patients that received empiric therapy, exhibited a higher likelihood of improper usage compared to those prescribed specific therapy (Fig. 5). Likewise, findings from a study conducted in Portugal indicated that over a third of patients receiving empiric ceftriaxone prescriptions were deemed inappropriate52. This surge in empiric therapy, notably prevalent in developing countries, like Ethiopia is largely attributable to limited access to diagnostic laboratories.

While empiric treatment may seem an attractive and cost effective treatment strategy, its widespread adoption often leads to inappropriate antibiotic usage53. Consequently, there is a pressing need for rapid diagnostic tests capable of identifying causative agents at the point of care. Such tests would enable healthcare providers to rapidly and accurately identify infections, facilitating the precise administration of narrow-spectrum antibiotics. This targeted treatment approach ensures optimal patient care and helps mitigate the emergence of antibiotic resistance, preserving the effectiveness of antibiotics for future generations54,55,56,57. Moreover, it reduces health care costs related to inappropriate antibiotic usage that are estimated in millions of dollars58.

Specific therapy, defined as the use of ceftriaxone after a definitive diagnosis has been established typically following culture and sensitivity results59, was notably low across the studies, ranging from only 1.6–19.1%. This indicates that the majority of ceftriaxone treatments were initiated without confirming the diagnosis, relying heavily on clinical judgment rather than objective diagnostic evidence.

This reliance on empiric therapy over specific therapy may highlight significant gaps in diagnostic capabilities or practices related to antibiotic stewardship in the studied hospitals. Such practices can lead to inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization, as treatments may be administered without ensuring that the antibiotic is necessary or effective for the diagnosed condition52,60,61. This situation highlights the need for education of healthcare staff, awareness of local antimicrobial resistance patterns, improved diagnostic protocols and adherence to evidence-based treatment guidelines to enhance the appropriateness of ceftriaxone use and minimize the risks associated with its overuse62,63.

Limitations of the study

Although this Systematic review and Meta-analysis provides a summarized overview of the inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization and its predictor factors in Ethiopia, its scope was restricted due to the exclusion of articles published in languages other than English and those lacking full texts. Consequently, this limitation may have led to an incomplete representation of the available literatures, possibly overlooking valuable insights.

Conclusion

The study reveals a high national pooled prevalence of inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization, standing at 55.24%. This highlights a significant hazard in the use of this antibiotic, suggesting potential instances of overuse, misuse or prescription practices that deviates from established guidelines. This noteworthy challenge can lead to the development of antibiotic resistance, increased healthcare costs, adverse drug reactions, and treatment failures. Addressing these issues requires a multifaceted approach involving improved antibiotic stewardship, better adherence to guidelines, and enhanced clinician education on appropriate antibiotic use.

Moreover, the current investigation suggests several factors, including Empiric therapy, multiple medication co-prescription, and certain hospital departments, particularly emergency and surgery wards, were significantly linked with increased likelihood of inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization. These observations emphasizes the urgent need for improved prescribing practices even within healthcare departments to mitigate the overuse or misuse of this critical antibiotic. In a nut shell, these findings offer valuable insights, to healthcare providers, researchers, and policymakers aiming to address the challenges associated with inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization both on a global scale and particularly within Ethiopia.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Tassew, S. G., Abraha, H. N., Gidey, K. & Gebre, A. K. Assessment of drug use pattern using WHO core drug use indicators in selected general hospitals: A cross-sectional study in Tigray region, Ethiopia. BMJ Open 11(10), e045805 (2021).

WHO. Rational use of medicines by prescribers and patients. Report by the secretariat. 16 (2004).

Wendie, T. F., Ahmed, A. & Mohammed, S. A. Drug use pattern using WHO core drug use indicators in public health centers of Dessie, North-East Ethiopia. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 21(1), 197 (2021).

Mamo, D. B. & Alemu, B. K. Rational drug-use evaluation based on World Health Organization core drug-use indicators in a tertiary referral hospital, Northeast Ethiopia: A cross-sectional Study. Drug Healthc. Patient Saf. 15–21. (2020).

WHO. The Pursuit of Responsible Use of Medicines: Sharing and Learning from Country Experiences (World Health Organization, 2012).

Soman, N., Panda, B. K., Banerjee, J. & John, S. M. A study on prescribing pattern of cephalosporins utilization and its compliance towards the hospital antibiotic policy in surgery ward of a tertiary care teaching hospital in India. Int. Surg. J. 6(10), 3614–3621 (2019).

Girma, S., Sisay, M., Mengistu, G., Amare, F. & Edessa, D. Antimicrobial utilization pattern in pediatric patients in tertiary care hospital, Eastern Ethiopia: The need for antimicrobial stewardship. Hosp. Pharm. 53(1), 44–54 (2018).

Sileshi, A., Tenna, A., Feyissa, M. & Shibeshi. W. Evaluation of ceftriaxone utilization in medical and emergency wards of Tikur Anbessa specialized hospital: A prospective cross-sectional study (2016).

Sasi, P., Mwakyandile, T., Manyahi, J., Kunambi, P., Mugusi, S. & Rimoy, G. Ceftriaxone prescribing and resistance pattern at a national hospital in Tanzania (2020).

Menkem, E. Z., Labo Nanfah, A., Takang, T., Ryan Awah, L., Awah Achua, K., Ekane Akume, S. et al. Attitudes and practices of the use of third-generation cephalosporins among medical doctors practicing in Cameroon. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2023 (2023).

WHO. Promoting Rational Use of Medicines: Core Components (World Health Organization, 2002).

Rehman, M. J. S., Alrowaili, M., Rauf, A. W. A. & Eltom, E. H. Ceftriaxone drug utilization evaluation (DUE) at Prince Abdulaziz Bin Moussae’ed Hospital, Arar, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Sudan J. Med. Sci. 14(4), 266–275 (2019).

Lee, H. et al. Evaluation of ceftriaxone utilization at multicenter study. Korean J. Int. Med. 24(4), 374 (2009).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, n71 (2021).

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. & Rothstein, H. R. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 1(2), 97–111 (2010).

Rücker, G., Schwarzer, G., Carpenter, J. R. & Schumacher, M. Undue reliance on I 2 in assessing heterogeneity may mislead. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 8, 1–9 (2008).

Higgins, J. P. & Green, S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (2008).

Lin, L. et al. Empirical comparison of publication bias tests in meta-analysis. J. General Int. Med. 33, 1260–1267 (2018).

Wells, G. A., Shea, B., O’Connell, D., Peterson, J., Welch, V., Losos, M. et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses (2000).

Qumseya, B. J. Quality assessment for systematic reviews and meta-analyses of cohort studies. Gastrointest. Endosc. 93(2), 486–94 (2021).

FMHACA. Standard Treatment Guidelines for General Hospital. FMHACA Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (2014).

Gelaw, L. Y., Bitew, A. A., Gashey, E. M. & Ademe, M. N. Ceftriaxone resistance among patients at GAMBY teaching general hospital. Sci. Rep. 12(1) (2022).

Drug use evaluation of ceftriaxone at Adama Hospital Medical College medical WARD, Adama, Ethiopia 2015 [Internet]. 2015 [cited 4/15/2024]. Available from: https://www.coursehero.com/file/220942727/ceftriaxonedocx/.

Garedow, A. W. & Tesfaye, G. T. Evaluation of antibiotics use and its predictors at pediatrics ward of Jimma Medical Center: Hospital based prospective cross-sectional study. Infect. Drug Resist. 15, 5365–5375 (2022).

Mama, M. et al. Inappropriate antibiotic use among inpatients attending Madda Walabu University Goba Referral Hospital, Southeast Ethiopia: Implication for future use. Infect. Drug Resist. 13, 1403–1409 (2020).

Abebe, F. A., Berhe, D. F., Berhe, A. H., Hishe, H. Z. & Akaleweld, M. A. Drug use evaluation of ceftriaxone: The case of Ayder Referral Hospital, Mekelle, Ethiopia. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 3(7), 2191 (2012).

Amare, F., Gashaw, T., Sisay, M., Baye, Y. & Tesfa, T. The appropriateness of ceftriaxone utilization in government hospitals of Eastern Ethiopia: A retrospective evaluation of clinical practice. SAGE Open Med. 9, 20503121211051524 (2021).

Ayele, A. A., Gebresillassie, B. M., Erku, D. A., Gebreyohannes, E. A., Demssie, D. G., Mersha, A. G. et al. Prospective evaluation of Ceftriaxone use in medical and emergency wards of Gondar university referral hospital, Ethiopia. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 6(1) (2018).

Ayinalem, G. A., Gelaw, B. K., Belay, A. Z. & Linjesa, J. L. Drug use evaluation of ceftriaxone in medical ward of Dessie Referral Hospital, North East Ethiopia. Int. J. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. 2(6), 711–717 (2013).

Bantie, L. Drug use evaluation (DUE) of Ceftriaxone injection in the in-patient wards of Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital (FHRH), Bahir Dar, North Ethiopia. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. 4, 671–676 (2014).

Geresu, G., Yadesa, T. & Deresa, B. Drug use evaluation of ceftriaxone in medical ward of Mizan Aman general hospital, Bench Maji Zone, South Western Ethiopia. J. Bioanal. Biomed. 10, 127–131 (2018).

Hafte, K., Tefera, K., Azeb, W., Yemsrach, W. & Ayda, R. Assessment of ceftriaxone use in Eastern Ethiopian Referral Hospital: A retrospective study. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2, 26–29 (2018).

Mehari, K. Evaluation of Ceftriaxone Utilization and Prescriber’s Opinion at Armed Forces Referral and Teaching Hospital, Addis Ababa (Addis Ababa University, 2017).

Muhammed, O. S. & Nasir, B. B. Drug use evaluation of ceftriaxone in Ras-Desta Memorial General Hospital, Ethiopia. Drug Healthc. Patient Saf 12, 161–168 (2020).

Sewagegn, N. et al. Evaluation of ceftriaxone use for hospitalized patients in Ethiopia: The case of a referral hospital. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Sci. Res. 3, 26–31 (2017).

Shegute, T., Hiruy, M., Hadush, H. & Gebremeskel, L. Ceftriaxone use evaluation in Western Zone Tigray Hospitals, Ethiopia: A retrospective cross-sectional study. BioMed. Res. Int. 2023 (2023).

Shimels, T., Bilal, A. I. & Mulugeta, A. Evaluation of ceftriaxone utilization in internal medicine wards of general hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A comparative retrospective study. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 8(26), 26 (2015).

Shimels, T. & Fenta, T. G. Assessment of ceftriaxone utilization in different wards of the federal police referral hospital in Ethiopia: A retrospective study. Ethiop. Pharm. J. 31(2), 141–150 (2015).

Taressa, D., Sosengo, T., Abera Jambo, E. M., Abdella, J. & Amare, F. Appropriateness of ceftriaxone prescription: A case of Haramaya hospital Eastern Ethiopia. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 12(3), 7 (2021).

Werede, A. et al. Drug use evaluation study of ceftriaxone in Ras Desta Damtew Memorial Hospital 2022 GC. Biomed. J. Sci Tech. Res. Soc. Dev. 50(1), 41221–6 (2023).

Jifar, W. W., Adugna, D., Gadisa, B., Debele, G. R. & Admasu, T. T. Retrospective drug use evaluation of ceftriaxone in resource limited setting in case of Bedele General Hospital, Ethiopia. pp 1–14 (2022).

Chang, Y. et al. The 5 min meta-analysis: Understanding how to read and interpret a forest plot. Eye 36(4), 673–675 (2022).

Deeks, J. J., Higgins, J. P., Altman, D. G. & Group, C. S. M. Analysing data and undertaking meta‐analyses. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. pp 241–84 (2019).

Bown, M. J. & Sutton, A. J. Quality control in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 40(5), 669–677 (2010).

Kutyabami, P. et al. Evaluation of the clinical use of ceftriaxone among in-patients in selected health facilities in Uganda. Antibiotics 10(7), 779 (2021).

Berhe, Y. H., Amaha, N. D. & Ghebrenegus, A. S. Evaluation of ceftriaxone use in the medical ward of Halibet National Referral and teaching hospital in 2017 in Asmara, Eritrea: A cross sectional retrospective study. BMC Infect. Dis. 19, 1–7 (2019).

Davey P, Brown E, Charani E, Fenelon L, Gould IM, Holmes A, et al. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital inpatients. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013(4).

Cella, E. et al. Joining forces against antibiotic resistance: The one health solution. Pathogens 12(9), 1074 (2023).

Salam, A., Al-Amin, Y., Salam, M. T., Pawar, J. S., Akhter, N., Rabaan, A. A. et al. editors. Antimicrobial resistance: A growing serious threat for global public health. Healthcare MDPI (2023).

Durham, S. H., Wingler, M. J. & Eiland, L. S. Appropriate use of ceftriaxone in the emergency department of a Veteran’s health care system. J. Pharm. Technol. 33(6), 215–218 (2017).

Malik, M. et al. Evaluation of the appropriate use of ceftriaxone in internal medicine wards of Wad Medani Teaching Hospital in Sudan. Int. J. Med. Sci. Clin. Invent. 7, 4757–4765 (2020).

Gorgulho, A. et al. Appropriateness of empirical prescriptions of ceftriaxone and identification of opportunities for stewardship interventions: A single-centre cross-sectional study. Antibiotics 12(2), 288 (2023).

McGregor, J. C. et al. A systematic review of the methods used to assess the association between appropriate antibiotic therapy and mortality in bacteremic patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45(3), 329–337 (2007).

Laxminarayan, R. et al. Antibiotic resistance—the need for global solutions. Lancet Infect. Dis. 13(12), 1057–1098 (2013).

Ayukekbong, J. A., Ntemgwa, M. & Atabe, A. N. The threat of antimicrobial resistance in developing countries: Causes and control strategies. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 6(1), 47 (2017).

Dhesi, Z., Enne, V. I., O’Grady, J., Gant, V. & Livermore, D. M. Rapid and point-of-care testing in respiratory tract infections: an antibiotic guardian?. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 3(3), 401–17 (2020).

Castro-Sánchez, E., Group WARNIN. Ten golden rules for optimal antibiotic use in hospital settings: The WARNING call to action. World J. Emerg. Surg. 18(50), 18–30 (2023).

Janssen, J. et al. Exploring the economic impact of inappropriate antibiotic use: The case of upper respiratory tract infections in Ghana. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 11(1), 53 (2022).

Altaf, U., Saleem, Z., Akhtar, M. F., Altowayan, W. M., Alqasoumi, A. A., Alshammari, M. S. et al. Using culture sensitivity reports to optimize antimicrobial therapy: Findings and implications of antimicrobial stewardship activity in a hospital in Pakistan. Medicina (Kaunas) 59(7). (2023).

Tinker, N. J. et al. Interventions to optimize antimicrobial stewardship. Antimicrob Steward Healthc. Epidemiol. 1(1), e46 (2021).

Abejew, A. A., Wubetu, G. Y. & Fenta, T. G. Assessment of challenges and opportunities in antibiotic stewardship program implementation in Northwest Ethiopia. Heliyon (2024).

Boltena, M. T. et al. Adherence to evidence-based implementation of antimicrobial treatment guidelines among prescribers in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 16(1), 137 (2023).

Gorgulho, A., Cunha, F., Alves Branco, E., Azevedo, A., Almeida, F., Duro, R. et al. Appropriateness of empirical prescriptions of ceftriaxone and identification of opportunities for stewardship interventions: A single-centre cross-sectional study. Antibiotics (Basel) 12(2) (2023).

Funding

No fund received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.T, D.G.D, B.B.T, D.E, O.A, A.Y, A.T.Y, E.A.S participated in conception, literature review, and data extraction. C.T and M.B.Y. did the analysis and interpretation of data. Z.D.A and K.F participated in manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tafere, C., Endeshaw, D., Demsie, D.G. et al. Inappropriate ceftriaxone utilization and predictor factors in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 14, 25035 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75728-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75728-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Effects of County Medical Community Central Pharmacy on antibiotic use in primary care: a multicenter quasi-experiment

International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy (2025)