Abstract

This study aimed to develop an extraction-free method for quantitative and qualitative detection of HBV DNA compared to traditional nucleic acid extraction. Paired serum and dried blood spot (DBS) samples from 67 HBsAg-positive and 67 HBsAg-negative individuals were included. Two samples with known HBV DNA titers (~ 109 copies/mL) were examined by extraction-free detection using three surfactants (0.2 to 1% of Sodium dodecyl sulfate:SDS, N-Lauroylsarcosine sodium salt:NL, Sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate:SDBS), two stabilizing agents (0.1 or 0.01% 2-Mercaptoethanol:2ME and 3.5 or 7% Bovine Serum Albumin:BSA) and two Taq polymerases (Fast Advanced and Prime Direct Probe). HBV DNA in all 67 HBsAg-positive and 67 HBsAg-negative serum and DBS samples was directly quantified by Rt-PCR using 0.4% SDS or 0.4% NL with Fast Advance or Prime Direct Probe Taq. Extraction-free amplification was also performed. Detection limits were varied by different surfactants and Taq. SDS combined with Fast Advanced Taq showed lower detection limits, while SDS with Prime Direct Probe Taq outperformed NL or SDBS-based detection. Adding 2ME to SDS improved detection limit with Prime Direct Probe Taq but not significantly compared to SDS alone. BSA did not significantly enhance detection limits but provided insights into sample stability. The senitivity and specificity of 0.4% SDS and NL in combination with either Fast advanced or Prime Direct Probe Taq polymerase in serum samples were > 90% and 100% resepctively, while it was > 80% and 100% respectively in DBS samples. Extraction-free HBV DNA amplification provided 100% identity with original genomes. Our study suggests that SDS, NL or SDBS-based extraction-free HBV DNA detection strategies using Prime Direct Probe Taq have potential to simplify and accelerate HBV DNA detection with high sensitivity and specificity in both serum and DBS samples, with implications for resource-limited settings and clinical applications. Utilizing surfactants with 2ME is optional, and further research and validation are necessary to broaden its application in real-world diagnostics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection continues to be a significant global health concern, affecting individuals worldwide1. According to WHO estimates, in 2022, approximately 254 million indiviuals were living with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection with a report of 1.2 million new infection each year. By the end of 2022, only 13% of people living with CHB had been diagnosed and approximately 3% had received HBV treament2. This has resulted in 1.1 million deaths, predominantly attributed to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)1. A recent report from the Polaris Observatory Groups at the Center for Disease Analysis in the United States, published in 2021, highlighted that no countries are on track to achieve the elimination goal of HBV by 20303. Addressing and rectifying this challenge is needed at national, regional, and global levels.

The timely and accurate detection of HBV DNA plays a crucial role in the diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of HBV-related diseases. Current methods for HBV DNA detection typically involve nucleic acid extraction, purification, and subsequent amplification using polymerase chain reaction (PCR)4. Since the discovery of PCR in the twentieth century, it has quickly become the gold standard for the diagnosis of infectious diseases, especially during emergencies5,6. With its high sensitivity and specificity, it plays a critical role in disease diagnosis and helps to identify pathogens at the molecular level, aiding in faster interventions and improved survival6.

DNA extraction is a common step in various DNA detection and analysis techniques, which involves isolating DNA from a biological sample to obtain a purified DNA sample for molecular analysis5,7 which had been reported as a gold standard test for diagnosing most infectious diseases including HBV8. However, it is expensive, time-consuming, requires trained personnel and well-equipped laboratories, which are hard to come by in resource-limited settings where infectious diseases are prevalent9. Consequently, these factors hinder the widespread adoption of such techniques, particularly in resource-limited settings. Thus, there is a growing interest in developing alternative methods that either eliminate or simplify the DNA extraction step, with the aim of reducing overall turnaround time, cost, and complexity associated with traditional techniques.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), N-Lauroylsarcosine sodium salt (NL) and sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate (SDBS), surfactants, which possess properties that allow them to disrupt viral particles, solubilize viral membranes, and release viral nucleic acids into solution, have emerged as potential candidates for extraction-free HBV DNA detection. The existance of HBeAg in the core of Dane particles had been demonstrated after treatment with SDS10. Based on this proven property of SDS, potential to streamline the diagnostic workflow, making it more accessible and feasible in various clinical and point-of-care settings.

Therefore, this study aimed to develop an extraction-free method for the quantitative and qualitative detection of HBV DNA. Furthermore, we aimed to compare the performance of these surfactant-based methods with traditional nucleic acid extraction approach to evaluate the effectiveness and reliability of the surfactant-based techniques in HBV DNA detection.

Methods

Subjects

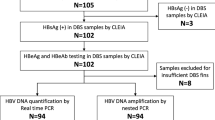

Assuming the expected sensitivity and specificity over 80%, a marginal error of 0.1, the confident level of 95%, the minimum sample size required for both HBsAg negative and positive samples was calculated to be 6211. Therefore, 67 HBsAg-positive samples with a known HBeAg status and 67 HBsAg negative samples which were also negative to HBsAb and HBcAb collected from pregnant women in Siem Reap, Cambodia were included in this study. The samples consisted of pairs of serum and dried blood spot (DBS) samples (HemaSpot™-HF, Spot on Science, CA, USA) collected in 2020 to assess mother-to-child transmission of HBV12. Both serum and DBS samples were stored at − 25°C until analysis.

Solubilizing HBV viral membrane in serum and DBS samples using surfactants

Two samples with known HBV viral load were used to examine the effect of surfactants in solubilizing HBV viral membrane: the first sample (CV20-1190) with viral load 2 × 109 copies/mL and the second sample (CV20-0828) with viral load 2 × 109 copies/mL.

Three different surfactants were used:

-

(i)

10% Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan)

-

(ii)

N-Lauroylsarcosine sodium salt (NL: C15H28NO3Na, Nacalai Tesque Inc, Kyoto, Japan)

-

(iii)

Sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate (SDBS: C18H29NO3S: SIGMA-ALDRICH Co., USA)

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS)13, N-Lauroylsarcosine (NL)14, and Sodium Dodecylbenzene Sulfonate (SDBS)15were selected for extraction-free HBV DNA detection due to their effectiveness in lysing viral particles while maintaining DNA integrity. These surfactants disrupt the viral envelope, releasing DNA without requiring traditional extraction methods. Therefore, the detection process becomes simpler and more accessible, particularly in resource-limited settings. SDS is a strong detergent that effectively lyses cells and viral membranes, though its potent denaturing properties may sometimes cause DNA shearing. NL, which is milder than SDS, provides effective lysis while minimizing DNA shearing, making it ideal for preserving high-molecular-weight DNA. SDBS, which is same as SDS, also offers strong denaturing capabilities, efficiently solubilizing proteins and lipids while protecting DNA from nucleases. Compared to other extraction-free methods like heat treatment16, which can cause DNA degradation and incomplete lysis, or acid/base treatment17,18,19,20, which is harsh and requires additional neutralization steps and requires prolong incubation at the required temperature, surfactant-based methods like SDS, NL, and SDBS offer a better balance between effective lysis and DNA preservation, simplifying the process and reducing the need for extra steps.

Each surfactant was mixed with distilled water to obtain a final concentration ranging from 0.2 to 1%. To solubilize the HBV viral membrane, 5 µL of each surfactant was added to 5 µL of serum samples accordingly. The mixture was incubated at 95°C for 5 min to enhance the action of SDS, NL, and SDBS in releasing the nucleic acid. Regarding DBS(HemaSpot™-HF) samples, one fin containing 7.5 μL of whole blood was detached and transferred to 2 mL Eppendorf tube containing 200 µL of elution buffer [Tris-buffered saline (TBS): 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Proclin 300, and 0.05% Tween 20 at pH 7.2]. After stirring the tubes for 1 hour, the DBS eluates were centrifuged at 3000 revolutions per minute (rpm) for 10 min, and the supernatants were filtered. Then, 5 µL of DBS eluate was then mixed with 5 µL of surfactants with concentration from 0.2 to 1% (SDS, NL, and SDBS) and incubated at 95°C for 5 min. After incubation of all serum and DBS samples at 95°C, 10 µL of distilled water was added to the mixture, pipetted to mix, and 5µL was used as the template DNA for the quantitative measurement of HBV DNA by the real time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) method.

Quantitative measurement of HBV DNA by real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

HBV surface protein-specific primers (forward primer: 5′CTTCATCCTGCTGCTATGCCT3′, reverse primer: 5′AAAGCCCAGGATGATGGGAT3’) and a probe (5′FAM-ATGTTGCCCGTCTAATTCCA-TAM3′) were used. The detection was performed using two different Taq polymerases: TaqMan™ Fast Advanced Master Mix (Applied Biosystem, ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) and Prime Direct Probe RT-PCR Mix (TAKARA Bio INC, Japan). The reaction mixture (20 µL) contained 10 µL of Taq polymerase, 0.5 µL each of the forward and reverse primers, 0.7µL of the probe, 3.3 µL of distilled water, and 5µL of template DNA. The thermal cycle included 2 min at 50 °C, 2 min at 90 °C, followed by 53 cycles of 10 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 60 °C. The viral load was then converted into copies per milliliter (copies/mL).

Examining the effect of 2-Mercaptoethanol on SDS surfactant

The same two samples were used to investigate the effect of 2-Mercaptoethanol (2ME: HSCH2CH2OH, SIGMA-ALDRICH INC., Tokyo, Japan) on SDS in solubilizing the HBV viral membrane and enhancing HBV DNA preservation by eliminating ribonuclease during cell lysis. The 0.1% and 0.01% v/v of 2ME were added to 0.4% SDS to achieve final concentrations of 0.5% and 0.41% v/v of the mixture, respectively. Four different strategies were performed: (i) detection of HBV DNA by ordinary HBV DNA extraction using the SMI-test, (ii) extraction-free HBV DNA detection using 0.4% SDS, (iii) extraction-free HBV DNA detection using a mixture of 0.5% SDS and 2ME, and (iv) extraction-free HBV DNA detection using a mixture of 0.041% SDS and 2ME. Each strategy used 5 µL of the sample to solubilize the viral membrane following the aforementioned procedure. Then, 5 µL of the final mixture was used as template DNA for viral load quantification using two different Taq polymerases: TaqMan™ Fast Advanced Master Mix and Prime Direct Probe RT-PCR Mix.

Examining the stabilizing effect of Bovine Serum Albumin in extraction free HBV DNA detection

Using the same two samples, Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA, pH 5.2, Nacalai Tesque Inc, Kyoto, Japan) was mixed with distilled water to prepare two different solutions with final concentrations of 3.5% and 7%. The solubilization of HBV DNA viral membrane was performed as per the aforementioned procedure, using 5 µL of 0.4% SDS and 5 µL of two serum samples. After incubation at 95 °C for 5 min, the mixture was then serially diluted from 10 to 10,000 times with (i) distilled water, (ii) 3.5% BSA, and (iii) 7% BSA solution. Later, 5 µL of the diluted mixture was used as the template DNA for quantitative measurement of HBV DNA by qPCR.

Quantitative detection of HBV DNA among 67 HBsAg-positive and 67 HBsAg-negative serum-DBS paired samples using the ordinary extraction method and different extraction-free method

All 67 HBsAg-positive and 67 HBsAg-negative serum-DBS paired samples were then detected for HBV DNA using the aforementioned extraction-free techniques with 0.4% SDS and 0.4% NL, respectively. Two different Taq polymerases were applied to compare their function and efficiencies. The HBV DNA quantification was performed by qPCR. Moreover, the same samples were extracted for HBV DNA using the ordinary extraction method (SMI-TEST EX R&D, Medical and Biological laboratories Co. Ltd, USA) strictly following the manufacturer’s instruction and HBV DNA was detected by qPCR using Fast Advanced Taq polymerase21.

Qualitative detection of HBV DNA by nested polymerase chain reaction (nested-PCR)

Twelve HBsAg positive serum samples with known viral load from 101 to 106 copies were then used to amplify HBV surface region (nt455-687: 232 base pairs) using the universal primer set; outer primers; S1-1 (forward: TCGTGTTACAGGCGGGGTTT), S1-2 (reverse: CGAACCACTGAACAAATGGC), and inner primers; S2-1 (forward: CAAGGTATGTTGCCCGTTTG), S2-2 (reverse, GGCACTAGTAAACTGAGCCA). First, 5 µL of serum samples were solubilized with 5µL of 0.4% SDS or NL. After incubation at 95°C for 5 min, 5 µL of the mixture was used as the template DNA for the amplification by nested PCR. The amplification was done by two rounds of nested PCR, each nested-PCR used 50µL of reaction mixture containing 0.25 µL of Ex Taq Host Start (TAKARA Bio. Inc., Shiga. Japan), 5 µL of 10 × Ex Taq Buffer, 4 µL of dNTP Mixture, 2 µL each of 10 nM forward and reverse primer, 31.75 µL of distilled water and 5 µL template DNA. The same thermal cycle was applied for both 1st and 2nd nested-PCR: 30 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min followed by final elongation at 72°C for 2 min. The amplified products were then examined by gel electrophoresis using 2.5% of 1:3 Agarose gel running at 100 V for 30 min and visualized under UV light with Ethidium Bromide (Nippon gene, Tokyo, Japan).

Sequencing of HBV surface partial amplicon

The amplified products were then direct sequenced by Sanger method using SeqStudio sequence Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and the corresponding inner primers (S2-1 and S2-2). The sequence data was visualized by Genetyx-Mac version 21.2 (Gentex Japan) and compare with the previously performed HBV genome submitted at GenBank through DDBJ with accession numbers: LC753663 (CV20-0752), LC753689 (CV20-0744), LC753646 (CV20-1261), LC753667 (CV20-0902), LC753668 (CV20-0092), LC753669 (CV20-0098), LC753674 (CV20-0544), LC753680 (CV20-0107), LC753654 (CV20-0201), LC753688 (CV20-0741), LC753651 (CV20-1487) and LC753686 (CV20-0487).

Ethic consideration

This study was approved by the Epidemiological research Ethic Committee of Hiroshima University (No. E-1693) and the Cambodian National Ethic Committee for Health Research (No. 223-NECHR). The written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before each study procedure. For those participants under 18 years old, the written informed consent was obtained from their legal guardians. All research activities adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Extraction free quantitative measurement of HBV DNA in serum samples using different surfactants and Taq polymerases

Using two HBsAg-positive serum-DBS paired samples with known HBV viral loads, the first sample (CV20-1190) with 2 × 109 copies/mL and the second sample (CV20-0828) with 2 × 109 copies/mL, we observed a nearly same titer (ranging from 2 × 109 to 1 × 1010 copies/mL) of HBV DNA was detected using 0.2% to 1% of SDS with Prime Direct Probe Taq in serum samples (Fig. 1a). However, in DBS samples, a titer approximately 10 times lower titer (ranging from 3 × 107 to 9 × 108 copies/mL) of HBV DNA was detected (Fig. 1d). Conversely, a nearly identical titer (ranging from 7 × 108 to 3 × 109 copies/mL) of HBV DNA was detected using 0.2 to 0.5% of SDS with Fast Advance Taq in serum samples (Fig. 1a), whereas in DBS samples, a titer approximately 100 times lower (ranging from 9 × 105 to 3 × 107 copies/mL) of HBV DNA was detected (Fig. 1d).

Quantitative amplification of HBV DNA by real-time polymerase chain reaction(qPCR). Quantitative amplification by qPCR of HBV DNA was performed on paired serum and DBS samples at varying concentrations of surfactants: (a) Sodium dodecyl sulfate (b) N-Lauroylsarcosine sodium salt and (c) Sodium dodecyl benzenesulfonate in serum samples and (d) Sodium dodecyl sulfate (e) N-Lauroylsarcosine sodium salt and (f) Sodium dodecyl benzenesulfonate in DBS samples. The HBV viral load is expressed as copies per milliliter on the y-axis, while surfactant concentrations, ranging from 0.2% to 1%, are presented on the x-axis. The red line indicates the Prime Direct Probe Taq measurement, and the blue line represents the Fast Advance Taq measurement. The round shapes and triangles depict measurements for the first and second samples, respectively.

By using the NL surfactants with a dilution ranging from 0.2% to 1%, a nearly the same viral titer (ranging from 1 × 109 to 4 × 109 copies/mL) and a titer approximately 10 times lower titer (ranging from 6 × 106 to 9 × 108 copies/mL) of HBV DNA were detected with Prime Direct Probe in serum (Fig. 1b) and DBS samples (Fig. 1e), respectively. Furthermore, a titer approximately 100 times lower titer (ranging from 2 × 106 to 4 × 107 copies/mL) and 1000 times lower titer (ranging from 7 × 104 to 3 × 107 copies/mL) of HBV DNA was detected using 0.2% to 1% of NL with Fast Advance Taq in serum (Fig. 1b) and DBS samples (Fig. 1e), respectively.

Similarly, a comparable viral titer (ranging from 2 × 109 to 5 × 109 copies/mL) and a titer approximately 10 times lower titer (ranging from 2 × 107 to 3 × 109 copies/mL) of HBV DNA were detected using 0.2% to 1% of SDBS with Prime Direct Probe Taq in serum (Fig. 1c) and DBS samples (Fig. 1f), respectively. Additionally, a titer approximately 10 times lower titer (ranging from 2 × 106 to 6 × 107 copies/mL) of HBV DNA was detected using 0.2% to 0.8% of SDBS with Fast Advance Taq in serum samples (Fig. 1c), while a titer approximately 1000 times lower titer (ranging from 9 × 105 to 7 × 106 copies/mL) of HBV DNA was detected using 0.2% to 0.4% of SDBS with Fast Advance Taq in DBS samples (Fig. 1f).

The effect of 2-Mercaptoethanol on SDS surfactant

Compared to HBV DNA detection by ordinary nucleic acid extraction-based and extraction free methods, despite adding 0.1% or 0.01% of 2ME to 0.4% of SDS, nearly same titer (9 × 108 to 4 × 109 copies/mL) and 100 times lower titer (1 × 106 to 2 × 107 copies/mL) of HBV DNA was detected by Prime Direct Probe and Fast Advance Taq respectively in serum samples (Fig. 2a). In DBS samples, 10 times lower titer (9 × 107 to 2 × 108 copies/mL) and 100 times lower titer (1 × 105 to 9 × 105 copies/mL) of HBV DNA was detected using Prime Direct Probe and Fast Advance Taq respectively (Fig. 2b).

Quantitative amplification of HBV DNA with the effect of 2-Mercaptoethanol (2-ME) on Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) surfactant. Quantitative amplification by qPCR of HBV DNA was performed on paired serum and DBS samples with the addition of different 2-ME concentration (0.1 to 0.4%) on the SDS surfactant. The HBV viral load is expressed as copies per milliliter on the y-axis, while surfactant concentrations, ranging from 0.2 to 1%, are presented on the x-axis. The red line corresponds to the Prime Direct Probe Taq measurement, while the blue line represents the Fast Advance Taq measurement. Circular and triangular markers indicate results for the first and second samples, respectively.

The stabilizing effect of Bovine Serum Albumin in extraction free HBV DNA detection

A decrease in HBV DNA titer was found from 8 × 109 to 8 × 107, 3 × 107, 1 ~ 2 × 106 and 1 ~ 5 × 105 copies/mL in serial dilution of 10 to 10,000 times dilution with distilled water and measured with Prime Direct Probe Taq. The dilution either with 3.5% or 7% Bovine Serum Albumin does not improve the detection efficacy of HBV DNA using Prime Direct Probe Taq. Using Fast Advance Taq, a drop of HBV DNA titer was found from 8 × 108 ~ 2 × 109 to 5 ~ 7 × 106, 1 ~ 3 × 106, 2 ~ 3 × 105 and 2 ~ 5 × 104 copies/mL in serial dilution of 10 to 10,000 times dilution with distilled water. The dilution either with 3.5% or 7% Bovine Serum Albumin does not improve the detection efficacy of HBV DNA using Fast Advance Taq (Fig. 3).

Quantitative amplification by real time polymerease chain reaction of HBV by serial dilution of different medium. Quantitative amplification by qPCR of HBV DNA was performed by serial dilution( No dilution to 10,000) of the different medium including water(long line), 3.5% Bovine serum albumin (ellipsis) and 7% Bovine serum albumin (long dash). The HBV viral load is expressed as copies per milliliter on the y-axis. The red color corresponds to the Prime Direct Probe Taq measurement, while the blue represents the Fast Advance Taq measurement. Circular and triangular markers indicate results for the first and second samples, respectively.

Quantitative detection of HBV DNA in 67 HBsAg-positive and 67 HBsAg-negative serum-DBS paired samples using different extraction-free method

HBV DNA was not detected in any of the 67 HBsAg-negative samples using any extraction-free methods or Taq polymerase. Of 67 HBsAg positive serum samples, the median HBV viral load detected by ordinary nucleic acid extraction and Fast Advance Taq was 2 × 104 copies/mL. While the median HBV viral load was 3 × 103, 1 × 105 and 2 × 106 copies/mL when detected by extraction free 0.4% SDS with Fast Advance Taq, 0.4% SDS with Prime Direct Probe Taq, 0.4% NL with Prime Direct Probe Taq, respectively. Using Prime Direct Probe Taq, there was no statistically significant difference in detecting HBV viral load between 0.4% SDS and 0.4% NL but the detection was significantly higher in Prime Direct Probe Taq either with 0.4% SDS (p = 0.0032) or 0.4% NL (p = 0.0069) than 0.4% SDS with Fast Advance Taq. There was no significant difference in detecting HBV DNA between ordinary nucleic acid extraction-based method and extraction free method either with 0.4% SDS and Primer Direct Probe or 0.4% NL with Prime Direct Probe Taq. (Fig. 4a). In the DBS samples, the HBV viral load detected by extraction free 0.4% NL with Prime Direct Probe Taq (median: 6 × 105 copies/mL) is significantly higher than those by 0.4% SDS with Prime Direct Probe (median: 1 × 105 copies/ml) (p = 0.0394) (Fig. 4b).

Quantitative Detection of HBV DNA in 67 HBsAg-positive and 67 HBsAg-negative serum-DBS paired samples. Detection of HBV DNA by different medium and PCR-Taq among 67 HBsAg positive and 67 HBsAg-negative (a) Serum samples (b) DBS samples. The HBV viral load is expressed as copies per milliliter on the y-axis and different nucleic acid extraction and measurement are presented on the x-axis. The red circular markers indicate HBeAg positive while the blue circular markers indicate HBeAg negative.

Considering the WHO cut off for antiviral prophylaxis for prevention of mother-to-child transmission(MTCT) of HBV DNA ≥ 200,000 IU/mL or 1.12 × 106 copies/mL22, the percent of HBsAg-positive pregnant women required for prophylaxis is varied based on the detection method used, 31.3% by ordinary nucleic acid extraction-based method, 22.4%, 29.9% and 50.8% by extraction-free 0.4% SDS with Fast Advance Taq, 0.4% SDS with Prime Direct Probe Taq, and 0.4% NL with Prime Direct Probe Taq respectively in serum samples (Fig. 4a). Similarly, with DBS sample, 25.4% of HBsAg-positive pregnant women needing antiviral prophylaxis by extraction-free 0.4% SDS with Prime Direct Probe and 44.8% by extraction-free 0.4% NL with Prime Direct Probe (Fig. 4b).

Sensitivity and specificity of all extraction-free methods

In serum samples, extraction-free HBV DNA detection using 0.4% SDS and Fast Advanced Taq polymerase showed a sensitivity of 94.03% (95% CI: 85.41–98.35%) and a specificity of 100% (95% CI: 94.64–100%) (Fig. 5a). When using 0.4% SDS and Prime Direct Probe Taq polymerase, the sensitivity was 92.54% (95% CI: 83.44–97.53%) and the specificity remained 100% (95% CI: 94.64–100%) (Fig. 5b). Using 0.4% NL and Prime Direct Probe Taq polymerase, the sensitivity increased to 95.52% (95% CI: 87.47–99.07%) with a specificity of 100% (95% CI: 94.64–100%) (Fig. 5c).

In DBS samples, extraction-free HBV DNA detection using 0.4% SDS and Prime Direct Probe Taq polymerase yielded a sensitivity of 80.60% (95% CI: 69.11–89.24%) and a specificity of 100% (95% CI: 94.64–100%) (Fig. 5d). When using 0.4% NL and Prime Direct Probe Taq polymerase, the sensitivity improved to 83.58% (95% CI: 72.52–91.51%) with the same specificity of 100% (95% CI: 94.64–100%) (Fig. 5e). The area undercurve was 0.97015, 0.96269, 0.97761, 0.90299 and 0.91791 respectively (Fig. 5).

Receiver Operation Curve (ROC)analysis of extraction free detection of HBV DNA. Sensitivity and speicificity of extraction free detection of HBV DNA in serum and DBS samples showed by the ROC for different medium : (a) 0.4% SDS + Fast Advanced Taq , (b) 0.4% SDS + Prime Direct Probe Taq, (c) 0.4% NL + Prime Direct Probe Taq in serum samples and, (d) 0.4% SDS + Prime Direct Probe Taq and (e) 0.4% NL + Prime Direct Probe Taq in DBS samples. The HBV qPCR is expressed as copies per milliliter. The red circular markers indicate HBeAg positive while the blue circular markers indicate HBeAg negative.

Amplification of HBV DNA by nested polymerase chain reaction (nested-PCR) and its subsequent sequencing

All six serum samples each having viral load from 101 to 109 copies/mL treated with 0.4% SDS was successfully amplified at HBV surface region (232 base pairs) but the amplification was limited to those serum samples having viral load ≤ 103 copies/mL. (Fig. 6) The sequence data compared to their original genome data previously submitted at GenBank through DDBJ was 100% identity without any mismatch reading or amplification induced mutation (data not shown).

Amplification of HBV DNA by nested polymerase chain reaction (nested-PCR). Amplification of HBV surface partial genome using extraction-free (a) 0.4% SDS treated HBsAg positive serum samples and (b) 0.4% NL treated HBsAg positive serum samples shown by gel electrophoresis with 100 base pairs marker. The original gel photo is provided in Supplementary figure.

Discussion

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains a substantial global health challenge, with millions of individuals living with chronic HBV infection and associated risks of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma1. One critical aspect of managing HBV-related diseases is the timely and accurate detection of HBV DNA. Conventional methods for HBV DNA detection involve labor-intensive and time-consuming steps, including nucleic acid extraction and purification. These limitations have hindered the widespread adoption of these techniques, particularly in resource-limited settings. In response to these challenges, this study explored the use of surfactants, specifically Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), N-Lauroylsarcosine Sodium Salt (NL), and Sodium Dodecyl Benzene Sulfonate (SDBS), to bypass DNA extraction step and streamline the diagnostic workflow 6).

SDS13, N-Lauroylsarcosine sodium salt (sarcosyl)14, and SDBS15 share several similarities in their roles during nucleic acid extraction. All three surfactants effectively disrupt cell membranes, aiding in the release of nucleic acids. They also denature proteins, which helps separate nucleic acids from protein complexes, and solubilize proteins and lipids from cellular membranes, facilitating the overall extraction process. Additionally, by denaturing proteins, including nucleases, all three surfactants help protect nucleic acids from degradation. However, NL is generally gentler on nucleic acids compared to SDS and SDBS, making it less likely to cause DNA shearing during extraction. This characteristic makes NL particularly preferable when working with high-molecular-weight DNA. On the other hand, SDS and SDBS are stronger denaturants, making them more effective for general protein removal, though they may be more damaging to delicate nucleic acids23.

Our study demonsteated the potential use of surfactants for extraction-free HBV DNA detection. By employing different surfactants and Taq polymerases, the study found varying detection limits, with SDS, NL, and SDBS showing promise as alternatives to traditional extraction methods. In serum samples, the surfactant SDS showed the lowest detection limit at a concentration of 0.8%, while NL and SDBS exhibited similar detection limits but at concentrations 100 times lower than SDS when using Fast Advance Taq polymerase. When using Prime Direct Probe Taq polymerase, NL and SDBS showed comparable detection limits to SDS. However, when testing in the DBS samples, the detection limits were generally lower than in serum samples, and NL and SDBS showed lower detection limits compared to SDS, particularly when using fast advance Taq polymerase. The lower viral titers found in DBS samples compared to serum samples might be attributed to the loss of HBV DNA titer due to the small volume of DBS samples and potential degradation of DNA through multiple steps in DBS processing including elution or extraction procedures, storage conditions, especially in samples with lower viral loads24,25. Several studies have demonstrated that HBV viral loads in DBS samples are comparatively lower than in corresponding serum or plasma samples26,27,28.

Both 2-Mercaptoethanol (2ME)15 and Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)29 play protective roles in nucleic acid extraction by stabilizing nucleic acids and preventing degradation. They achieve this through interactions with proteins, but their mechanisms differ. 2ME acts as a reducing agent, breaking disulfide bonds in proteins and denaturing them, which helps prevent nucleases from degrading the nucleic acids. In contrast, BSA stabilizes the extraction environment by binding to proteins and enzymes, sequestering them to prevent contamination and unwanted interactions with nucleic acids. While both agents contribute to the stabilization process, 2ME does so by altering protein structure, and BSA by acting as a “protein sink” that shields nucleic acids from harmful interactions23.

2ME is considered to improve HBV DNA extraction efficiency by acting as a strong reducing agent, breaking disulfide bonds in proteins and aiding in the denaturation and disruption of protein structures that are tightly bound to the HBV DNA30. Additionally, 2ME is effective in removing covalently linked proteins attached to the 5’ terminus of HBV DNA, which are resistant to heating with SDS. When used in combination with other reagents such as SDS, 2ME enhances the overall yield of HBV DNA31. Importantly, while 2ME denatures proteins, it does not damage the DNA itself, thereby preserving the integrity of the extracted viral genome 30. In our study we revealed that the addition of either 0.1% or 0.01% of 2ME to SDS surfactant further improved the detection limit for Prime Probe Taq polymerases, but it was not significantly differed from SDS alone. This suggests that treatment with 2ME to SDS does not change the detection limit significantly, so it is optional to include.

BSA had been utilized in numerous laboratory molecular techniques as DNA restriction enzyme digestions in order to enhance the thermal stability and extend the half-life of restriction enzymes during these reactions32. Due to its property, BSA also have been investigated in PCR and prior studies have reported that BSA provide a beneficial effect on the yield of PCR (and qPCR) amplification of DNA extracted from feces, freshwater, or marine water33,34. In our study, we assessed the stabilizing effect of BSA in extraction-free HBV DNA detection. Our result showed that BSA did not significantly increase the detection limits, suggesting that it may not play a significant role in improving the stability or detection efficiency of the method, however, it provides valuable insights into potential additives for preservation during the testing process.

The quantitative detection of HBV DNA in 67 HBsAg-positive and 67 HBsAg-negative serum-DBS paired samples using different extraction-free methods revealed that both SDS and NL, combined with various Taq polymerases, could detect HBV DNA, with the median HBV viral load ranging from 1 × 105 to 2 × 106. Fast Advance Taq polymerase generally provided lower detection limits (3 × 103) compared to Prime Direct Probe Taq polymerase in serum samples. NL demonstrated a higher detection limit than SDS in both serum and DBS samples when using Prime Direct Probe Taq. In addressing the prevention of MTCT of HBV, which WHO defines as introducing antiviral prophylaxis for pregnant women with HBV DNA ≥ 200,000 IU/mL or 1.12 × 106 copies/mL22, our study revealed that using nucleic acid-free 0.4% NL with Prime Direct Probe Taq met the prophylaxis needs in a higher percentage of serum samples (50.8%) and DBS samples (44.8%) compared to other extraction nucleic acid-free methods (22.4–31.3%). The results suggest that the choice of surfactant and polymerase can be tailored based on the specific requirements of the diagnostic application.

In comparison to the existing extraction-free HBV DNA detection, LAMP (Loop-mediated Isothermal Amplification)16,35,36 offers a balance of high sensitivity (91%) and specificity (97%) at a moderate cost ($8–14 USD) and can deliver results in 60–95 min. It’s simple and suitable for low-resource settings but is prone to contamination and false positives if not optimized. RPA (Recombinase Polymerase Amplification)37 provides even higher sensitivity (98.6%) but lower specificity (88.2%) at a lower cost (< $7 USD) and a faster time (< 60 min). However, it is prone to nonspecific amplification, making optimization critical. MIRA (Multienzyme Isothermal Rapid Amplification)38, although lacking specific sensitivity and specificity data, is cost-effective ($6.5 USD) and fast (10 min), but requires further validation for HBV and more complex reagent preparation. RAA (Recombinase Aided Amplification)39 offers high sensitivity (95.7%) and perfect specificity (100%) at a low cost ($3.7 USD) and short time (30 min), though it has slightly reduced sensitivity compared to qPCR and requires precise heat treatment. PSR-LFB (Polymerase Spiral Reaction with Lateral Flow Biosensor)40 matches qPCR and LAMP in sensitivity and specificity, is user-friendly, and ideal for point-of-care diagnostics, but requires specific primers and optimization to prevent non-specific amplification. Finally, CRISPR/Cas12a-based Amplification-free Detection41 stands out for its ultra-sensitivity, detecting down to 0.1 pM, and potential for multiplexing, but it is costly and complex, especially in basic labs. Our method is simple and user friendly, it requires treating with the surfactants and short time for incubation at 95°C for 5 min. It is simple and user friendly, not include complicated procedure and does not require the trained personnel and equipment compared to the existing DNA extraction free method. The cost is cheap and reasonable, 1.7 USD per sample which is 3 times cheaper than the ordinary PCR method (4.9USD per sample), 5–8 times cheaper than LAMP (8–14 USD / sample), 4 times cheaper than RPA (< 7USD) and MIRA (6.5 USD/ sample) and 2 times cheaper than RAA (3.7 USD per sample) and the operation time takes one hour. Our method presented high sensitivity (> 92% in serum samples, > 80% in DBS samples) and specificity (100% in both serum and DBS samples). In real time PCR, the universal primers are used, however, mismatches can potentially reduce the detection sensitivity. Therefore, when a new variant strain emerges, it is necessary to review, and then the modification of the primer and probe is required.

Moreover, in terms of qualitative detection, the nested PCR amplification of HBV DNA in serum samples with known viral loads successfully amplified the target region for most of the samples. All the sequencing results showed 100% identity with the original genome data submitted to GenBank. This demonstrates the reliability of the extraction-free method for qualitative HBV DNA detection. These methods have the potential to simplify the diagnostic workflow, reduce turnaround time, and increase accessibility in various clinical and point-of-care settings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study has made significant strides in developing an extraction-free method for the quantitative and qualitative detection of HBV DNA in both serum and DBS samples. Our study suggests surfactants either SDS or NL or SDBS based extraction-free HBV DNA detection startegy using Prime Direct Probe Taq polymerase have the potential to simplify and accelerate HBV DNA detection with high sensitivity (> 90%) and specificity (100%), with implications for resource-limited settings and clinical applications. Utilizing surfactants with 2ME is optional and further research and validation are necessary to broaden its application in real-world diagnostics.

Data availability

The data generated or analyzed during the current study were fully described in the main text and is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

World_Health_Organization. Hepatitis B: WHO Fact Sheet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b. Accessed 3 Jul 2024.

World_Health_Organization. Global Hepatitis Report 2024: Action for Access in Low- and Middle-income Countries (World Health Organization, 2024). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Polaris_Observatory_Group. Country Dashboard on HBV and HCV elimination Polaris Observatory Center for Disease Analysis 2021. https://cdafound.org/polaris-countries-dashboard/ Accessed 3 Jul 2024.

Mitchell, J. RT-PCR Protocols. Methods in Molecular Biology, Vol. 193: O’Connell J, ed. ($99.50.) Humana Press, 2002. ISBN 0 89603 875 0. J. Clin. Pathol. 56, 400 (2003).

Schmitz, J. E., Stratton, C. W., Persing, D. H. & Tang, Y. W. Forty years of molecular diagnostics for infectious diseases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 60, e0244621. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.02446-21 (2022).

Krishna, N. K. & Cunnion, K. M. Role of molecular diagnostics in the management of infectious disease emergencies. Med. Clin. North Am. 96, 1067–1078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2012.08.005 (2012).

Tang, Y. W., Procop, G. W. & Persing, D. H. Molecular diagnostics of infectious diseases. Clin. Chem. 43, 2021–2038 (1997).

Bhatt, A. et al. CLEVER assay: A visual and rapid RNA extraction-free detection of SARS-CoV-2 based on CRISPR-Cas integrated RT-LAMP technology. J. Appl. Microbiol. 133, 410–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.15571 (2022).

Liu, W., Yue, F. & Lee, L. P. Integrated point-of-care molecular diagnostic devices for infectious diseases. Acc. Chem. Res. 54, 4107–4119. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00385 (2021).

Takahashi, K. et al. Demonstration of hepatitis B e antigen in the core of dane particles1. J. Immunol. 122, 275–279. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.122.1.275 (1979).

Hajian-Tilaki, K. Sample size estimation in diagnostic test studies of biomedical informatics. J. Biomed. Inform. 48, 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2014.02.013 (2014).

Bunthen, E. et al. Residual risk of mother-to-child transmission of HBV despite timely Hepatitis B vaccination: A major challenge to eliminate hepatitis B infection in Cambodia. BMC Infect Dis. 23, 261. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-023-08249-1 (2023).

Yu, Y., Pandeya, D. R., Liu, M. L., Liu, M. J. & Hong, S. T. Expression and purification of a functional human hepatitis B virus polymerase. World J. Gastroenterol. 16, 5752–5758. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i45.5752 (2010).

Carratalá, J. V. et al. Enhanced recombinant protein capture, purity and yield from crude bacterial cell extracts by N-Lauroylsarcosine-assisted affinity chromatography. Microb. Cell Fact. 22, 81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-023-02081-7 (2023).

Sood, A. K. & Aggarwal, M. Evaluation of micellar properties of sodium dodecylbenzene sulphonate in the presence of some salts. J. Chem. Sci. 130, 39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12039-018-1446-z (2018).

Notomi, T. et al. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, E63. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.12.e63 (2000).

Changotra, H. & Sehajpal, P. K. An improved method for the isolation of hepatitis B virus DNA from human serum. Indian J. Virol. 24, 174–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13337-013-0155-y (2013).

Costa, J. et al. Microwave treatment of serum facilitates detection of hepatitis B virus DNA by the polymerase chain reaction. Results of a study in anti-HBe positive chronic hepatitis B. J. Hepatol. 22, 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-8278(95)80257-6 (1995).

Kaneko, S., Feinstone, S. M. & Miller, R. H. Rapid and sensitive method for the detection of serum hepatitis B virus DNA using the polymerase chain reaction technique. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27, 1930–1933. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.27.9.1930-1933.1989 (1989).

Sambrook, J. & Russell, D. W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual 3rd edn, Vol. 1 (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2001).

Ko, K. et al. Existence of hepatitis B virus surface protein mutations and other variants: Demand for hepatitis B infection control in Cambodia. BMC Infect. Dis. 20, 305. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05025-3 (2020).

World_Health_Organization. Guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, care and treatment for people with chronic hepatitis B infection.

Natarajan, V. P., Zhang, X., Morono, Y., Inagaki, F. & Wang, F. A modified SDS-based DNA extraction method for high quality environmental DNA from seafloor environments. Front. Microbiol. 7, 986. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00986 (2016).

Mohamed, S. et al. Dried blood spot sampling for hepatitis B virus serology and molecular testing. PLoS ONE 8, e61077. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0061077 (2013).

Kikuchi, M. et al. Dried blood spot is the feasible matrix for detection of some but not all hepatitis B virus markers of infection. BMC Res. Notes 15, 287. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-022-06178-x (2022).

Stene-Johansen, K. et al. Dry blood spots a reliable method for measurement of hepatitis B viral load in resource-limited settings. PLoS ONE 11, e0166201. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0166201 (2016).

Garg, R., Ramachandran, K., Jayashree, S., Agarwal, R. & Gupta, E. Evaluation of blood samples collected by dried blood spots (DBS) method for hepatitis B virus DNA quantitation and its stability under real life conditions. J. Clin. Virol. Plus 2, 100111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcvp.2022.100111 (2022).

Vinikoor, M. J. et al. Hepatitis B viral load in dried blood spots: A validation study in Zambia. J. Clin. Virol. 72, 20–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2015.08.019 (2015).

Al-Soud, W. A. & Rådström, P. Purification and characterization of PCR-inhibitory components in blood cells. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39, 485–493. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.39.2.485-493.2001 (2001).

Urban, S. et al. Isolation and molecular characterization of hepatitis B virus X-protein from a baculovirus expression system. Hepatology 26, 1045–1053. https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.1997.v26.pm0009328333 (1997).

Gerlich, W. H. & Robinson, W. S. Hepatitis B virus contains protein attached to the 5’ terminus of its complete DNA strand. Cell 21, 801–809. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(80)90443-2 (1980).

Kreader, C. A. Relief of amplification inhibition in PCR with bovine serum albumin or T4 gene 32 protein. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62, 1102–1106. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.62.3.1102-1106.1996 (1996).

Woide, D., Zink, A. & Thalhammer, S. Technical note: PCR analysis of minimum target amount of ancient DNA. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 142, 321–327. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.21268 (2010).

Tarrand, J. J., Krieg, N. R. & Döbereiner, J. A taxonomic study of the Spirillum lipoferum group, with descriptions of a new genus, Azospirillum gen. nov. and two species, Azospirillum lipoferum (Beijerinck) comb nov. and Azospirillum brasilense sp. nov.. Can J Microbiol 24, 967–980. https://doi.org/10.1139/m78-160 (1978).

Vanhomwegen, J. et al. Development and clinical validation of loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assay to diagnose high HBV DNA levels in resource-limited settings. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 27(1858), e1859-1858.e1815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2021.03.014 (2021).

Chen, C. M. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of LAMP assay for HBV infection. J Clin. Lab. Anal. 34, e23281. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.23281 (2020).

Mayran, C. et al. Rapid diagnostic test for hepatitis B virus viral load based on recombinase polymerase amplification combined with a lateral flow read-out. Diagnostics. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12030621 (2022).

Sun, M. L., Zhong, Y., Li, X. N., Yao, J. & Pan, Y. Q. Simple and feasible detection of hepatitis a virus using reverse transcription multienzyme isothermal rapid amplification and lateral flow dipsticks without standard PCR laboratory. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 51, 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/21691401.2023.2203198 (2023).

Shen, X. X. et al. A rapid and sensitive recombinase aided amplification assay to detect hepatitis B virus without DNA extraction. BMC Infect. Dis. 19, 229. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3814-9 (2019).

Lin, L., Guo, J., Liu, H. & Jiang, X. Rapid detection of hepatitis B virus in blood samples using a combination of polymerase spiral reaction with nanoparticles lateral-flow biosensor. Front. Mol. Biosci. 7, 578892. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2020.578892 (2020).

Du, Y. et al. Amplification-free detection of HBV DNA mediated by CRISPR-Cas12a using surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Anal. Chim. Acta 1245, 340864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2023.340864 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank to all participants for their active participation, all the midwives for their assistance in sample recruitmment and collection.

Funding

This research was partly funded by a grant from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Core-to-Core Program (Grant number: JPJSCCB20210010 and JPJSCCB20240009) and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (JPMH19HC1001, JPMH22HC1001) and Fund for the promotion of Joint International Research (Fostering Joint International Research-B; JP18KK0262) and Grants in aid for Scientific Research-A (24H00657). The funder of the study has no role in study design, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.T. and K.T. conceptualized the study. K.R., O.V., and J.T. supervised the field work. B.E., K.K., A.S., T.A., collected data. K.K., L.M.L., Z.P., S.O., and K.T. conducted the laboratory analysis. G.A.A., C.C., K.K, and K.T. participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data. T.A. and J.T. supervised statistical analyses. K.K., and L.M.L drafted the manuscript. J.T. revised the manuscript critically. All authors reviewed, revised, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ko, K., Lokteva, L.M., Akuffo, G.A. et al. A comparative study of extraction free detection of HBV DNA using sodium dodecyl sulfate, N-lauroylsarcosine sodium salt, and sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate. Sci Rep 14, 25442 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75944-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75944-7