Abstract

Early detection and correct identification of the optic disc (OD) on scanned retinal images are significant for diagnosing and treating several ophthalmic conditions, including glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy. Conventional methods for detecting the OD often struggle with processing retinal images due to noise, changes in illumination, and complex overlapping images. This study presents the development of effective and accurate fixation of the optic disc using the Bitterling Fish Optimization (BFO) algorithm, which enhances the processes of OD imaging in speed and precision. The proposed method begins with image enhancement and noise suppression for preprocessing, followed by applying the BFO algorithm to locate and delineate the OD region. The performance evaluation of the algorithm was conducted within several public domain retinal images, including DRIVE, STARE, ORIGA, DRISHTI-GS, DiaRetDB0, and DiaRetDB1 datasets about some internal metrics: sensitivity (SE), specificity (SP), accuracy (ACC), DICE overlap coefficient, overlap and time of processing respectively. The technique based on BFO provided better results, with 99.33%, 99.94%, and 98.22% accuracy achieved for OD in DRIVE, DRISHTI-GS, and DiaRetDB 1, respectively. The approach also demonstrated high overlaps and good DICE results, with a DICE coefficient of 0.9501 for the DRISHTI-GS database. On average, the processing time per image was less than 2.5 s, proving the approach’s efficiency in computations. The BFO approach has demonstrated its effectiveness and scalability in detecting optic discs in retinal images in an automated manner. It showed impressive performance levels in terms of computation time and accuracy and was variation resistant irrespective of the quality of the image and the pathology present on it. This method holds significant potential for clinical use, providing a meaningful way of diagnosing and managing ocular disease at an early stage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the field of medical imaging, detecting and accurately identifying different regions or anatomical structures is a crucial aspect of computer-based diagnosis and management1,2,3, and more so in the field of ophthalmology, where the optic disc (OD) is a crucial reference point. This region is central to the diagnosis and treatment of a wide range of eye disorders, such as glaucoma and diabetic hypertensive retinopathy, where monitoring of the health of the retina and changes in the diseases over time requires the proper location of the OD in retinal images4,5.

However, traditional manual approaches to OD localization are time-consuming, subjective, and susceptible to inter-observer variability6. These constraints are problematic for assessing the quality of the output in instances of diagnosis in which several people are working on the same subject, and especially in mass screening programs where quick and accurate diagnoses are required7,8,9. More recently, machine learning and deep learning algorithms have shown promising results in OD localization, offering improved accuracy and robustness10. However, these models typically require large amounts of labeled data for training and are computationally intensive, making them less feasible for real-time clinical use11. In order to address these challenges, automated techniques for OD detection are drawing increasing attention. classical image processing approaches like edge detection and template matching are well documented in the literature, but these techniques often struggle with complex characteristics of retinal images, such as noise, different illumination, and overlapping anatomical structures12. These models, however, are usually data hungry, requiring annotated images for efficient training, and more often than not, very computationally intensive, thus not practical for use in fast-paced clinical environments13.

Given these difficulties, optimization techniques based on nature have become much more effective alternatives mainly because of their effectiveness in exploring and exploiting very complicated search spaces14,15. Among these, the BFO, an optimization algorithm using the foraging behavior of bitterling fish as its foundation, has been used successfully to address various complex optimization issues16, This paper presents a novel method of OD detection of retinal images that takes advantage of the capabilities of the BFO algorithm and its adaptive learning, exploration, and exploitation efficiencies.

The suggested approach utilizing BFO-based algorithms overcomes a few constraints associated with the current techniques employed for OD detection mechanisms. First and foremost, it is less dependent on the availability of large datasets and complicated training procedures, making it a more compact and adaptable approach. Furthermore, such accuracy in locating the OD region even in noisy, low-illumined, and overlapping retinal layers is made possible by the BFO algorithm’s proficiency in solving complex optimization tasks. Moreover, such a method is computationally efficient and thus can be implemented in a clinical real-time setting.

The primary objective of this research is to showcase the advantages of the BFO algorithm when implemented in OD detection with a focus on potential applications in automated retinal image analysis. The development of this method, which is more accurate and faster in locating the optic disc, will help improve the early diagnosis and treatment of eye diseases. The following sections elaborate on the methodology, experimental findings, and evaluation against other approaches, all showcasing the possibilities of the BFO algorithm as a deployable and cost-effective skill for clinicians.

Problems statements

Several issues emerge in the precise detection, as well as the location of the OD in retinal images, which is a crucial step in the clinical management of various eye disorders, such as glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy. Most of the traditional techniques have several major flaws, including:

-

1.

Noise and Imaging Variations: Noise, vibrations, and even illumination levels affect the quality of OD detection, as the retinal images are often obtained under several conditions.

-

2.

Obstruction by internal structures: Other internal features may impede the optic disc, making the segmentation process challenging and potentially introducing errors.

-

3.

Dependence on Intrinsic Parameters: Several algorithms available today depend on selected parameters, which can compromise their robustness and efficiency when used on varying datasets.

-

4.

To address these challenges, this study proposes implementing the BFO algorithm as a novel enhancement technique for optic disc localization for the first time. This implementation not only improves processing time and results but also efficiently addresses the limitations identified in traditional methods.

Main contributions

-

1)

Innovation application of the BFO Algorithm: The study presents the BFO algorithm as a new approach for the development of automatic OD detection and segmentation in retinal images. This is the first application of BFO in the field of medical imaging analysis, thereby indicating vast possibilities for its application in diagnosis improvement.

-

2)

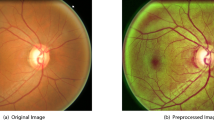

Comprehensive Image Preprocessing: A robust preprocessing stage is also put forward, including sophisticated image enhancement and noise reduction. These techniques significantly improve the quality of retinal images before OD localization, thereby reducing issues associated with noise and illumination, especially in retinal imaging.

-

3)

Validation of Performance on Many Datasets: The BFO algorithm has been validated on many publicly available retinal image datasets, and these include the DRIVE, DRISHTI-GS, STARE, ORIGA, DIARETDB0, and DIARETDB1 datasets.

-

4)

Effective Processing Efficiency: The algorithm can run and process the images within less than 2.5 s on average, making it suitable for a clinical setup that requires fast turnaround times for analysis. This speed, therefore, makes the BFO method acceptable for use in real-time systems water retinal image analysis.

-

5)

Enhanced Performance as Compared to the Existing Techniques: a comprehensive assessment reveals that the BFO-based technique surpasses numerous current OD detection techniques, especially regarding accuracy and processing speed. Therefore, it is envisaged that it will be the best option for ophthalmology in the coming clinical uses.

-

6)

Scalability and Adaptability: The BFO algorithm’s performance is robust, scalable, and adaptable in equal measure to accurately operate with changes in the quality of images or anatomy of the retinal images. This wide range of flexibility enhances its use in various clinical situations to enhance the management of eye conditions through early diagnosis and treatment interventions.

-

7)

Foundational Perspectives on Future Research: This study provides a basis for investigating other nature-based optimization algorithms in the context of imaging science. It also provides direction on future works intending to improve the BFO technique in the treatment of different eye diseases. It thus plays a role in the improvement of diagnosis.

The second section presents the literature review on previously conducted works on OD detection methods. Section 3 explains the approach used, including image processing and localization of OD by the BFO method. Section 4 explains how the experiments were carried out, shows the findings, and compares results obtained using other techniques. Finally, Sect. 5 concludes the paper and looks at the prospects for further research.

Literature review

Detecting the OD in retinal images is a crucial task in computer-aided diagnosis systems designed to identify and monitor various ocular diseases17. Over the years, numerous methods and algorithms have been proposed to automate this process, leveraging advancements in computer vision, image processing, and machine learning techniques18. In this section, some of the prominent approaches and recent developments in OD detection are reviewed, offering insights into the strengths and limitations of existing methods.

The geometric data of the retinal image vasculature is often leveraged in numerous studies for OD detection. The approach introduced in19 identified the OD as the central point of the vascular tree by focusing on where the blood vessels converge. The detection of the convergence of the vascular tree involved identifying the extremities of linear structures like blood vessels. Reference20 identified the OD based on a new approach that uses the point where all retinal vessels meet and originate. The authors found the OD by looking at how blood vessels are positioned and how bright the OD is. Their method has two steps: first, they figure out where the OD is horizontally on the image, then they make sure they’ve got the correct vertical position. Additionally, several researchers employ OD detection methods according to brightness and pattern matching. In21, the authors describe a method where they start by making the brightness of the green channel in the image standard. Then, they adjust the contrast. They use a pattern showing the direction of blood vessels in the retina to find matches in the image. Meanwhile, Muangnak et al.22 employ a hybrid method to detect the OD. This approach combines vessel vector-based phase portrait analysis and vessel transform. In23, a technique for locating the OD using convolutional neural networks is introduced. In24, the author proposes a technique for automatically specifying OD in retinal fundus images without relying on blood vessels or a background mask. Such an approach uses the features of the OD and employs a circular operator concept. In25, describe a study where the OD was located based on the contrast in intensity between the OD and neighboring vessels. Additionally, a line operator is used to address the constraints of the method above. The authors figure out where the blood vessels and the OD start by comparing how bright they are compared to each other. In26, a validation approach relies on both the brightness of the retinal image and details about blood vessels to find the OD. In reference27, employ the feature match method to identify symmetry among a chosen original OD image and any provided query visual. Moreover in28, an OD detection method based on the firefly algorithm, coupled with removing noise in the images through a median filter. In27, an approach was introduced based on the features of the OD, employing traditional image processing algorithms, incorporating thresholding, circular object recognition, and perimeter identification through the Hough transform. Due to the bright nature of the OD and the dark appearance of the blood vessels emerging from it, Bharkad introduced a quirpele filter29. This filter aims to minimize the variation in brightness, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of subsequent segmentation applications. In30, a shadow correction operator is employed specifically for the green channel of the image. Its purpose is to diminish gradual changes in the background. The research endeavor focused on creating and validating a computerized technique for quantifying ocular cyclotorsion through analysis of digital fundus images, demonstrating strong concordance with specialist assessments. This automated system ensures accuracy and effectiveness and holds promise in facilitating meticulous diagnosis and objective assessment of various ocular conditions31. A technique detecting the OD-related area and depression relying on specific mathematical techniques was introduced32. Watershed transformation and geodesic reconstruction were used mainly for this purpose.

In33, the OD location detection involved identifying the OD center through the highest local variance. Additionally34, primarily identifies the OD by its circular shape and higher brightness than surrounding structures in the image. Morphological operations utilizing watershed transformation and geodetic reconstruction are employed in35. In36, the authors employed Markov random processes for vessel removal and introduced an adjustment factor for OD segmentation. Finally37, involved training a neural network for OD segmentation.

The advent of machine learning and deep learning methodologies has brought about a revolutionary shift in the realm of optic disc (OD) diagnosis within ophthalmology38. These sophisticated computational approaches are pivotal in both automating and refining the precision of OD detection, segmentation, and the diagnosis of associated diseases through the analysis of retinal images39.

Deep learning, a subset within the domain of machine learning, stands out as an influential asset for OD diagnosis, owing to its innate capacity to autonomously derive hierarchical representations from unprocessed data40.

OD detection has extensively relied on conventional image processing methods, including techniques rooted in thresholding, edge detection, and morphological operations. For instance, a method proposed by Staal et al. relies on thresholding and morphological operations for OD detection in retinal images41. While such methods are computationally efficient, they may lack robustness in handling variations in image quality and pathology.

OD detection has seen the application of machine learning techniques, notably supervised learning algorithms like support vector machines (SVMs) and random forests42.

In43, the combination of SVM and active contour models was employed for precise OD localization in retinal images. Similarly, in44, introduced a method according to a cascaded CNN-RNN architecture for OD detection. While these approaches have demonstrated promising results, they may necessitate extensive amounts of annotated data for training, a challenge often encountered in medical imaging applications.

This research presented a new computer-assisted diagnosis (CAD) system for detecting glaucoma based on machine learning and soft computing techniques, achieving accuracy rates as high as 98.46% by improving the efficiency of a great number of features. while it shows advantages such as enhanced diagnostic outcomes and the scope for more use, challenges include the constraints of dependency on image quality and the need for an expert to approve the diagnosis45.

The study46, introduces an automated method for glaucoma detection using the fast Fuzzy C-Mean method, achieving a total accuracy of 96.0% on retinal fundus images while significantly improving processing speed.

The study presents an AI and IoT-based predictive model for glaucoma detection from Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) images, achieving 99% accuracy and enabling automated, remote screening. While it offers high performance and efficient patient monitoring, challenges include dependence on image quality, implementation complexity, and a limited dataset47.

The proposed system of screening for glaucoma is up to 99% accuracy but with a feature reduction of more than 75% which improves the overall efficiency and the diagnostic performance of the system48.

This research on glaucoma detection employs a Differential Evolution multi-objective feature selection technique, resulting in enhanced classification performance with fewer features with KNN. Although the approach shows improved results, it is restrained due to the limited feature set and the KNN algorithm, which calls for prudent execution and testing49.

Deep learning has revolutionized medical image analysis, including OD detection, by enabling the development of end-to-end trainable models capable of learning complex hierarchical features from raw image data. Notable architectures such as CNNs are extensively utilized for this task50. For example, a deep learning technique was introduced for the automated grading of diabetic retinopathy, incorporating OD detection as a preprocessing step51. Similarly, in52 introduced a framework for deep learning for the joint segmentation of OD and cup in glaucoma assessment. Despite achieving remarkable performance, deep learning methods often demand significant computational resources and annotated datasets for training.

Nature-inspired optimization algorithms are revolutionizing complex problem-solving across domains, with a particular impact on image processing and computer vision. For instance53, showcased a PSO-enhanced deep neural network for OD segmentation, leveraging six search mechanisms and transfer learning. This innovative approach yielded significantly improved segmentation quality and outperformed alternative methods despite challenges in computational complexity and dataset reliance.

In54, a preprocessing technique utilizing the bat algorithm for optic disc detection. The method demonstrated remarkable accuracy and efficiency across healthy and diseased images, offering automated zooming capabilities that surpassed existing accuracy, specificity, and speed techniques. Its potential as a solution for retinal image segmentation is vast.

Further advancing the field55, proposed a Glowworm Swarm Optimization algorithm for automated optic cup detection. Despite potential challenges in computational demands and image characteristics, the approach achieved a 3.2% reduction in overlapping error and high accuracy across datasets, underscoring its potential to enhance glaucoma diagnosis systems.

In56, a method that achieved outstanding accuracy across diverse datasets, robustly addressing image artifacts and quality variations despite extended processing times and vessel extraction dependence. Its performance highlights the potential for clinical applications.

As researchers continue to push boundaries, the Bitterling Fish Optimization algorithm emerges as a promising, yet largely untapped, avenue. Inspired by the foraging behavior of bitterling fish, its optimization prowess could be transformative for image processing challenges like OD detection.

In summary, existing approaches for OD detection in retinal images have made significant strides in automating this critical task. Traditional methods offer simplicity and efficiency but may lack robustness in handling diverse image characteristics. Machine learning and deep learning techniques provide more sophisticated solutions but require substantial computational resources and annotated data. Nature-inspired optimization algorithms, such as the BFO algorithm, offer an alternative approach with potential benefits regarding efficiency and adaptability. In this investigation, the BFO algorithm is proposed for OD identification in retinal images to explore its capabilities and potential in this domain.

Materials and methods

Dataset

The experiments were conducted on openly accessible retinal image datasets, focusing on automating vessel segmentation, a crucial aspect of diabetic retinopathy screening, as demonstrated in DRIVE41, The system utilizes ridge extraction and line element composition to partition images for feature vector computation and classification with a KNN classifier. Through the evaluation of a dataset of 40 labeled images, an impressive AUC of 0.952 was achieved, showcasing superior performance compared to rule-based approaches. Despite encountering challenges such as manual labeling and sensitivity to image artifacts, the system’s supervised nature enables it to adapt to intricate features, suggesting promising prospects for improving segmentation accuracy in retinal image analysis. In STARE19, the aim was to automatically locate the optic nerve in retinal images using a novel algorithm called fuzzy convergence, achieving an 89% detection rate on a healthy and diseased retina dataset. Four method variations were explored, with the combined fuzzy convergence and equalized brightness approach showing the highest overall performance, indicating the potential for broader applications and future research avenues. In DIARETDB157, the experiments aimed to establish a standardized evaluation methodology and a comprehensive image database for diabetic retinopathy diagnosis, addressing the lack of a unified benchmark in medical image processing. Findings emphasized the baseline method’s performance, particularly in detecting hard exudates, prompting the need for improvements and outlining future steps to enhance the database and evaluation methodology. Lastly, in ORIGA58, the study aimed to create an automated system using genetic algorithms to locate and segment the optic nerve head in eye fundus images. It utilized domain knowledge to guide the process, generating hypothesis points akin to ONH contour pixels and employed genetic algorithms to identify an ellipse approximating the ONH. Evaluation of 110 eye fundus images showcased competitive results, with experiments optimizing genetic algorithm parameters and establishing a final parameter configuration. The study emphasized the method’s robustness, generalization capability, and potential to furnish critical parameters delineating the ONH shape.

These datasets provide ground truth annotations for OD locations, enabling quantitative evaluation of the suggested approach. Authors dedicated to the development of retina image analysis methods globally utilize these datasets. Moreover, they exhibit distinct characteristics, including variations in brightness and size, with some containing images with multiple pathologies. The specifications of images in all four datasets have been detailed in Table 1.

This analysis made use of ground truths on the OD boundary and DRIVE from the DIARETDB1 dataset59. STARE and DRIONS had specialists outlining their ground truths concurrently.

Optimized bacterial foraging algorithm for accurate optic disc detection in retinal images

The BFO approach is uniquely used to detect the OD in retinal images, where each candidate solution represents a fish exploring possible locations for the OD. The algorithm imitates how fishes forage in water where they look for food in their surroundings as well as looking for already known promising locations to locate the OD due to some image features.

Fish Movement for OD localization

In the BFO algorithm, each fish symbolizes a possible position of the OD within the retinal image. These fishes swim over the image in two different regions of the image based on certain features such as intensity, shape, and texture that indicate the region that is most likely to contain the OD. Since fish in nature employ various methods of foraging, the algorithm itself does that by ensuring every region of the retinal image is searched for OD detection.

Population behavior

A population of fish is initialized, and each member of the population examines the possible OD location. During this process, fish with better fitness, which is calculated from the proximity to the image-based OD features of the closest position, are chosen to be explored further. This two-part approach of global search (looking towards new regions) and local search (taking the known good candidates’ area) enables the BFO algorithm to improve the search for the OD in the image effectively.

Enhancement of attributes

The BFO algorithm assesses each potential OD location on a constant basis and weighs factors that are vital for each candidate OD detection, such as contrast, circularity, brightness among others. These features are instrumental in facilitating optimal discrimination of OD structures from other structures present within the retinal scan image. Gradually, as a sequence of possible image under analysis increases, the algorithm moves towards the most probable position of the OD with the aid of these image properties in particular.

Adaptation of parameters

The efficiency of using the BFO algorithm for processing OD images highly depends on properly adjusting such parameters as population size, step size, and mutation rate. These parameters control how the fish is moved in the picture and how it is picked up. These controls are necessary for the algorithm not to go off the required focus but to maintain a reasonable exploration. Adjusting those controls is essential when seeking a precise and quick OD of retina images.

It is promising because the BFO algorithm has been modified to address the nature of the problem, which concerns the detection of ODs, thus allowing it to search the area for possible positions of the ODs in images of the retina. The optimization of image features and parameter settings allows the algorithm for accurate localization of the optic disc, which is an important part of many vision-based applications.

Enhancing the detection of Optic Disc using fitness function in bacterial foraging optimization algorithm

The fitness function leveraged in the BFO method for OD detection rates each candidate OD position location based on the measured image features such as intensity, contrast, circularity, shape, and brightness among others. These features are essential in identifying the OD from surrounding tissues on the retinal image. In this way, the algorithm promotes regions that would be refined and optimized better by assigning higher fitness values to OD characteristics. This method improves the algorithm in locating the OD region as expected, even in a challenging retinal image.

Every approach to the issue is akin to a bitterling fish, presented by Eq. (1). The generation of several bitterling fish populations can be accomplished by creating random populations:

The variable D denotes the number of variables for decision-making associated with every approach. Similarly, the variable i represents a specific answer within the issue.

The BFO algorithm encourages the creation of random populations, which sustains a great degree of solution diversity, allows for the effective search of the search space, and avoids its early convergence to local solutions. Such a way of random initialization also imitates the natural foraging behavior of fishes, enabling the algorithm to perform efficient exploitation and exploration in equal measures, subsequently leading to better optimization results. In decision-making, Eq. 2 provides the meaning of the initial populations, defined within specific coordinates intervals:

where \(\:{F}_{i}^{j}\:\)is the position of the fish j-th in the i-th generation, while l and u denote the limits of the search space. The variable \(\:r\) is a random number distributed uniformly in the range of [0, 1].

This implies that the initial position of each fish is generated in the range defined by [\(\:l\), \(\:u\)], providing appropriate initial points for decision-making. Also, by incorporating the random number \(\:r\), the algorithm can produce different starting positions to create more room for search within the solution space. Each fish is assigned a value based on its ability to choose the best ‘oysters’ linked to that fish’s value. A function \(\:F\) is defined as evaluating the performance of the fish and facilitating the iterations of the process aimed at finding the best solution.

Every solution or fish can explore the issue and locate proper mating oysters. In the suggested technique, every fish can position itself near proper shells. An individual fish can navigate to locate an oyster, targeting and moving towards it. The purpose oyster remains unnoticed by other fish and is seized by the pursuing fish. Equation (3) is employed to articulate the state of oyster ownership:

In this Equation, \(\:{F}_{i}^{t}\) and \(\:{F}_{i}^{t+1}\) represent the current and new positions, respectively, of a fish in iterations t and t + 1 for the ith answer. \(\:{F}^{*}\) stands for the optimal solution, and \(\:{F}^{+}\) denotes one of the worthy oysters randomly selected from the population. The parameters \(\:\zeta\:\) and \(\:r\) are random numbers between 1 and 0. The variable J denotes the movement steps or how quickly the fish moves towards or away from the oyster. It decreases with each algorithm iteration due to the fish’s reduced activity after mating. This reduction in J helps shift the search from global to local. Equation (4) is utilized to implement the reduction in parameter J:

In this equation, \(\:J\left(1\right)\) represents the initial value. In J(t), J is represented in mathematical notation (cursive). The equation describes the dynamics of J over iterations. J (1) signifies the initial phase and jump value for each fish in the primary phases of iterations. The variables 𝑡 and 𝑀𝑎𝑥𝐼𝑡 correspond to the present and highest number of iterations, respectively. Each fish’s step and jump for the repeating iteration t is what J (t) implies.

Generating random values Eq. 5: Eq. 5 proposes a technique based on the projection of fish populations that employs trigonometric functions to generate random values. The equation is represented as:

This approach utilizes the cosine function to provide some values within a certain range, simulating reasonable foraging behavior. Thus, ƌ\(\left(t\right)\) is projected back to an angle through the function cosine inverse.

By applying the cosine function to this angle, it becomes possible to obtain a new value ƌ\(\left(t+1\right)\). This process fills the solution space with values that mimic fish foraging behavior, that is, moving and scattering randomly, which is very important for the processes of search simulation in BFO algorithms.

Governance of \(\:J\) over iterations Eq. 6: An iterative algorithm naturally questions how often the value of \(\:J\) should be updated, as well as how to control its quantity. Equation 6 is the \(\:J\) value in a stepwise manner in BFO.

Initial Value Adjustment: The term \(\:J\left(1\right)-\frac{J\left(1\right).t}{Maxt}\:\)a mechanism where \(\:J\left(1\right)\:\)is gradually decreased over several iterations about \(\:t\:\)and a maximum threshold \(\:Maxt.\:\)This method provides for the gradual reduction of the objective function or performance index ‘ \(\:J\)’ with varying numbers of iterations.

Incorporation of Randomness: In this case, \(\:J\left(t+1\right)\:\) can introduce an element contained in  Eq. 5 , which allows alteration of the value of \(\:J\left(t+1\right).\) this randomness helps the technique avoid getting stuck in local optima, as small changes in the function can lead to significant effects.

Eq. 5 , which allows alteration of the value of \(\:J\left(t+1\right).\) this randomness helps the technique avoid getting stuck in local optima, as small changes in the function can lead to significant effects.

In summary, through parametrization, Eq. 6 resolves the dynamics of \(\:J\:\)by introducing decay and random external factors, which encourages minimizing transport costs. This is useful for the BFO algorithm as it supports convergence to the best possible solution while exploring different regions of the solution space. This dual mechanism is critical for a close approximation of natural fish population foraging behavior, leading to improved optimization results.

In BFO algorithms, the search for the optimal solution unfolds progressively, exploring a larger space around the optimum. Hence, it becomes imperative to diminish the P over time, satisfying the next standard of Eq. (3) with the situation of r > P, which is highly probable. A function resembling the behavior of the arctangent, as exemplified by Eq. (7), governs the evolution of the parameter P.

The value of t represents the iteration count, and denotes the reduction power. The likelihood of two search types in Eq. (3) diminishes as the difference becomes smaller. When a fish attempts to escape without seizing the oyster, a different fish guards it, deterring the approaching fish and prompting it to seek an alternative location. Equation (8) is employed for escaping or unintentional searching for a fish that has not successfully captured oysters:

M refers to the average location where the bitterlings usually gather. Consequently, following an escape event, a fish can explore the space between the average and optimal positions or venturing into random areas within the problem space. Equation (9) calculates the population’s center of gravity. In the BFO algorithm, Eq. 9 calculates the mean position or center of the fish swarm.

where \(\:{F}_{i}^{t}\:\)represents the position of i-th fish at time t, that is, fish number n. This equation simplifies the dispersal of fish, which is their mean location, after aggregating the distribution of all individuals.

Upon discovering an oyster, a male species is capable of taking the attention of a female, laying eggs in the oyster, and then fertilizing the eggs, giving rise to new fish in the vicinity of the existing fish.

The equation proposed in Eq. 10 explains in detail the mechanisms for fertilization and reproduction within fish groups:

where, \(\:{F}_{i}^{t+1}\) depicts how posits on the i-th fish will be updated in the next time step. concentric shells. while \(\:R\) typically ranges from values 0 to 2. It usually starts with a value of 2 and reduces over the iterations of the BFO. Thus, upon discovering an oyster, a male fish can entice a female, leading to the laying and fertilization of eggs inside the oyster, resulting in new fishes emerging close to the already existing ones. In the case of an issue aimed at reduction, the chance of losing a fish is determined by Eq. (11):

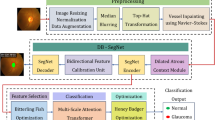

The likelihood of eliminating the solution \(\:{F}_{i}^{t}\:\) denoted as \(\:d\left({F}_{i}^{t}\right)\), is based on its corresponding objective function value \(\:f\left({F}_{i}^{t}\right)\). Figure 1 provides an overview of OD detection in retinal images employing the BFO algorithm.

In the pursuit of finding the optimal threshold value, the BFO algorithm unfolds through the subsequent steps:

-

Step 1: Configure essential BFO parameters, encompassing the size of the population, iteration count, dimensions, J, P, and more. Specify the objective function and initialize the starting population.

-

Step 2: Evaluate the primary population matrix using the objective function.

-

Step 3: Set BestSol or F* and define parameters J, ƌ, and P.

-

Step 4: Update J(t) and update P and and the formula \(\text{F}_{i}^\text{t+1}=\text{J.F}^{\text t}_\text{i}+(\text{F}^+-\text{J.F}^{\text t}_\text{i}).\zeta;\)

-

Step 5: Assess the population using the objective function and & Set F*

-

Step 6: Present the segmentation solution.

Results and discussion

The developed approach for detecting the OD in human retinal images utilized the BFO technique on publicly accessible databases such as DRIVE and STARE. The present study, in particular, focuses on the OD region of the eye fundus to facilitate early treatment of eye-related disorders. The performance of the approach is assessed using the following indices commonly employed in the literature: sensitivity (SE), specificity (SP), accuracy (ACC), and Dice coefficient (DICE), which measures how accurately the OD is located within the image context.

The efficiency proposed methodology is evaluated by assessing sensitivity, optic disc overlap, specificity, Dice coefficient, and accuracy. These parameters are calculated based on the values of true positive (TP), false positive (FP), true negative (TN), and false negative (FN), as shown in Table 2. For a visual representation, refer to Fig. 2.

The sensitivity parameter evaluates the proposed technique in accurately segmenting the actual OD. This is achieved by assessing the segmented OD boundary area (As) compared to the ground truth area (Ag), using the area of intersection divided by the area of union. In contrast, specificity measures the capability of the algorithm to detect an area that is not that of the OD and gives the true negative rate. The Dice coefficient is a strategic measure of the area between the detected OD and the provided ground truth, being the ratio of the intersection and union of the two areas. The overall accuracy indicates the percentage of correctly predicted pixels referring to the TPs and the TNs, which are true positive and negative, respectively. Higher average specificity (SP), Dice coefficient (DICE), accuracy (ACC), and overlap values indicate better performance of the segmentation of the OD.

The approach was executed utilizing MATLAB 2023a on a computer powered by an 8 GHz Intel Core i7-2410 CPU and 8 GB RAM. The results obtained using the method are presented in Table 3, which provides a comprehensive summary.

The results of the segmentation analysis, along with other details, are presented in Table 3, which depicts that the method proposed yields an average of 83.20%. 89.07%, 81.04%, 87.91%, 85.24%, and 79.66% regions overlapping for OD segmentation across the datasets DRIVE, DRISHTI-GS, STARE, ORIGA, DIARETDB1, and DIARETDB0, respectively. Furthermore, the technique demonstrated impressive average accuracies of 99.33%, 99.94%, 98.21%, 99.86%, 98.22%, and 99.71% for the same databases, respectively. Notably, the DRISHTI-GS database is more challenging, particularly because it contains many cases, in contrast to the STARE database, which primarily consists of more advanced and aggressive cases. Table 4 presents a comparative analysis of the performance of the proposed method against other techniques evaluated in the literature.

Table 4 provides a detailed evaluation of the results obtained through the proposed methodology as presented in the literature, along with its comparison with other existing techniques. The results highlight the efficacy of the proposed approach in successfully segmenting the OD region from retinal images. The values of SE and SP corresponding to the OD detection were found to be 0.9076 and 0.9998, respectively, for the DRISHTI-GS Dataset, indicating the algorithm’s accuracy in distinguishing true positives from true negatives. The accuracy of the overall proposed technique is 0.9994 on the DRISHTI-GS dataset, indicating its efficiency in localizing the OD compared to the true values provided. In addition, the visibility DICE coefficient, which is the measure of the overlap of the detected optic disc and the true optic disc, is 0.9501, proving the capability of the algorithm to achieve a clear-cut image of the OD region.

The datasets selected for this research include many fundus images in which the OD appears to have low and similar exudates. These image types seem to have undergone transformation challenges such as distortions, reflections, and uneven lighting. Figure 3 demonstrates how the proposed method accurately identifies OD, even from normal and abnormal retinal images.

It is necessary to acknowledge the limitation of the existing method, particularly regarding its sensitivity to parameter tuning, which may yield inconsistent results for different datasets. Further studies are expected to mitigate these parameters and evaluate the method on large sets of data representing many different types of retinal diseases.

In summary, the BFO approach is a viable option for the automatic localization of the optic disc in retinal images, thus enabling prompt treatment and prevention of eye diseases. This has great relevance to clinical practice and future work in automated eye-care systems that improve diagnosis and, therefore, the patients’ health.

In order to increase the OD boundary, segmentation area is achieved through the application of ellipse fitting. Figure 4 illustrates the result of the proposed method for the STARE datasets.

Figure 5 shows the results of OD detection with the proposed methodology on images obtained from DiaRetDB0, DiaRetDB1, ORIGA, and DRISHTI-GS datasets.

All the images in the datasets were assessed quantitatively, as depicted in Fig. 6. Every point in this scatter plot represents the difference between the estimated location of the OD based on the retinal image and the ground truth one, thereby demonstrating the robustness of the method in defining the OD based on retinal images. The results from T-OD analysis were also applied to images in the DRIVE, DiaRetDB1, and STARE datasets, with the correct disc location given by a cross (×) in each case. Importantly, throughout the process, the input image sizes remained constant, providing evidence for the processing times achieved by the proposed method.

In Fig. 6, the x-axis represents the number of retinal images processed, while the y-axis represents the difference between the estimated location of the optic disc as determined by the proposed model and the ground truth location. Additionally, the figure includes markers methods, including those from the DRIVE, STARE, DiaRetDB1, and DRISHTI-38 databases. By examining the distribution of these markers, one can objectively assess the performance of the proposed technique in comparison to other techniques outlined in the analysis.

Table 5 displays the timeframes needed for the BFO algorithm to locate the OD of the DRIVE, STARE, DiaRetDB0, DiaRetDB1, ORIGA, and DRISHTI-GS datasets.

The evaluation of outcomes confirms the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed OD detection technique based on the BFO algorithm in retinal images. The configuration pattern searches for and captures the perfect solution, found in the placement of the OD, using the natural foraging tendencies of these species of fish called BFO. One of the key benefits of the BFO optimization algorithm is the ability of the algorithm to maintain excellent exploratory ability and, at the same time, focus on the area with potential solutions to the OD. Thus, such provision allows the algorithm to adapt to the differences in quality, pathology, and anatomy of retinal images. Further, thanks to the population approach to optimization incorporated in the BFO algorithm, it is possible to work with several solutions simultaneously, increasing the chances of the optimal solution being found. This is especially advantageous when it is difficult to determine the OD, as it might be blended, distorted, or even within other structures.

The proposed method has several practical advantages, such as speed of operation, ease of use, and scope of application. The simple application of the algorithm and the simple process of adapting its parameters make it possible to use it for research and practice in medical image processing. In addition, the BFO algorithm has a built-in feature of parallelism and reconfigurability, allowing its effective use in systems for automated analysis of retinal images in a mode close to real-time.

In the last few decades, notable advances have been made in computer vision and machine learning, especially in retinal imaging optic disc (OD) detection, which has revolutionized the method of diagnosing and treating eye conditions. Among these, deep learning methods based on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), in particular, stand out as the most significant contributors to the enhanced efficiency and accuracy of optic disk delineation. These advanced techniques can learn complex representations from medical images and generalize effectively to different retinal features, allowing.

quicker and more accurate optic disc detection. The BFO algorithm represents one of the emerging alternatives aimed at providing a better solution than the existing ones. In contrast, most conventional methods often struggle with image processing tasks due to the background elements, poor image qualities, or the presence of noise. the BFO algorithm, which relies on the foraging behavior of bacteria, is utilized to combine the global and the local optimization in determining the optic disc region.

Furthermore, these developments have not only mechanized and improved the method of OD detection but have also opened up the possibility of diagnosing life-threatening eye diseases like glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy much earlier. These machine learning systems can also process and analyze retinal images as they are, removing the risk of delays between snapshots and static images. This allows for dynamic monitoring of the condition and more rapid and efficient treatment of eye disorders. In addition, these technologies incorporate into the healthcare systems the cost and time required for diagnosis and treatment, enabling the patients to receive more timely care and improving their overall outcomes.

Future work

Current progress in studying the BFO algorithm highlights several promising research avenues for future exploration. While we have emphasized the necessity for strategic parameter tuning and the incorporation of additional datasets, it is essential to investigate how the BFO algorithm can be further enhanced through integration with other machine learning methodologies. For instance, combining BFO with deep learning techniques, particularly those utilizing Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), could leverage the strengths of both approaches. The BFO algorithm can optimize the hyperparameters of CNN models, potentially leading to improved performance in optic disc (OD) detection across diverse retinal structures.

Furthermore, extending the application of the BFO algorithm to include other retinal features, such as exudates and microaneurysms, would significantly broaden its scope and clinical relevance. This expansion not only enhances the algorithm’s versatility but also facilitates the development of a comprehensive automated system for retinal image analysis.

Additionally, implementing methodologies such as ensemble learning and transfer learning would prove beneficial. For example, constructing an ensemble model that incorporates the BFO algorithm alongside other optimization techniques could enhance both robustness and accuracy. Moreover, employing transfer learning would enable the BFO algorithm to adapt effectively to different datasets, ensuring its performance across various clinical scenarios without the need for extensive retraining.

Integrating real-time data processing capabilities into the BFO framework could also greatly improve its usability in clinical settings by allowing for the continuous monitoring of patients. Such advancements would enable rapid analysis of retinal images, significantly aiding in the early detection of serious ocular conditions and ultimately enhancing overall patient care.

Conclusion

In this study, the Bitterling Fish Optimization (BFO) algorithm introduces an innovative technique for OD detection in human retinal images. Leveraging the foraging behavior of bitterling fish, the suggested method effectively localized the OD with competitive accuracy and efficiency. Through systematic experimentation and evaluation of publicly available datasets, including the DRIVE and STARE databases, the efficacy and robustness of the BFO-based approach for automated OD detection are demonstrated. The outcomes demonstrate that the BFO algorithm achieves high sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and DICE, indicating its ability to delineate the OD region in retinal images accurately. The algorithm’s adaptive exploration and exploitation strategies enable it to handle variations in image quality, pathology, and anatomical variability, making it suitable for real-world applications in clinical settings. The proposed method offers several advantages: computational efficiency, simplicity, and scalability. By providing a reliable and efficient solution for automated OD detection, the BFO algorithm has the potential to streamline the diagnostic workflow, facilitate the timely detection of ocular diseases, and improve patient outcomes in ophthalmology. While the results are promising, there are opportunities for further research and improvement. Future work could focus on refining the algorithm’s parameters, exploring alternative optimization techniques, and evaluating its performance on larger, more diverse datasets. Additionally, integrating the proposed method into comprehensive retinal image analysis systems could enhance its utility for clinical practice. In conclusion, the proposed BFO-based approach represents a valuable contribution to the field of medical image analysis, offering a promising solution for OD detection in human retinal images. By harnessing the principles of nature-inspired optimization, the algorithm demonstrates its potential to advance the automation of retinal image examination and provide the prompt diagnosis and management of ocular diseases.

Data availability

The dataset was obtained from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/andrewmvd/drive-digital-retinal-images-for-vessel-extractionhttps://cecas.clemson.edu/~ahoover/stare/https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/nguyenhung1903/diaretdb1-standard-diabetic-retinopathy-databasehttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21095735/https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/lokeshsaipureddi/drishtigs-retina-dataset-for-onh-segmentation .

References

Shukla, A.K. (Ed.). (2021). Medical Imaging Methods: Theory and Applications (1st ed.). CRC Press.https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003112068. ISBN 9781003112068

Cui, H., Hu, L. & Chi, L. Advances in computer-aided medical image processing. Appl. Sci. 13 (12), 7079 (2023).

Bhandarkar, A. et al. Deep learning based computer aided diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a snapshot of last 5 years, gaps, and future directions. Artif. Intell. Rev. 57 (2), 1–62 (2024).

Lee, D. K., Choi, Y. J., Lee, S. J., Kang, H. G. & Park, Y. R. Development of a deep learning model to distinguish the cause of optic disc atrophy using retinal fundus photography. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 5079 (2024).

Naz, H., Nijhawan, R. & Ahuja, N. J. Clinical utility of handheld fundus and smartphone-based camera for monitoring diabetic retinal diseases: a review study. Int. Ophthalmol. 44 (1), 1–28 (2024).

Nawaz, M. et al. An efficient deep learning approach to automatic glaucoma detection using optic disc and optic cup localization. Sensors. 22 (2), 434 (2022).

Nazir, T., Irtaza, A. & Starovoitov, V. Optic disc and optic cup segmentation for glaucoma detection from blur retinal images using improved mask-RCNN. Int. J. Opt. 1–12, 2021 (2021).

Almubarak, H., Bazi, Y. & Alajlan, N. Two-stage mask-rcnn approach for detecting and segmenting the optic nerve head, optic disc, and optic cup in fundus images. Appl. Sci. 10 (11), 3833 (2020).

Civit-Masot, J., Domínguez-Morales, M. J., Vicente-Díaz, S. & Civit, A. Dual machine-learning system to aid glaucoma diagnosis using disc and cup feature extraction. IEEE Access. 8, 127519–127529 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Wu, Y., Tong, K., Chen, H. & Yuan, Y. Review of visual simultaneous localization and mapping based on deep learning. Remote Sens. 15 (11), 2740 (2023).

Taye, M. M. Understanding of machine learning with deep learning: architectures, workflow, applications and future directions. Computers. 12 (5), 91 (2023).

Morales, S., Naranjo, V., Angulo, J., Legaz-Aparicio, A. G. & Verdu-Monedero, R. Retinal network characterization through fundus image processing: significant point identification on vessel centerline. Signal. Process. Image Commun. 59, 50–64 (2017).

Panchigar, D. et al. Machine learning-based CFD simulations: a review, models, open threats, and future tactics. Neural Comput. Appl. 34 (24), 21677–21700 (2022).

Bahr, T., Vu, T. A., Tuttle, J. J. & Iezzi, R. Deep learning and Machine Learning Algorithms for Retinal Image Analysis in neurodegenerative disease: systematic review of datasets and models. Transl Vis. Sci. Technol. 13 (2), 16 (2024).

Sreng, S., Maneerat, N., Hamamoto, K. & Win, K. Y. Deep learning for optic disc segmentation and glaucoma diagnosis on retinal images. Appl. Sci. 10 (14), 4916 (2020).

Zareian, L., Rahebi, J. & Shayegan, M. J. Bitterling fish optimization (BFO) algorithm. Multimed Tools Appl. 83, 75893–75926 (2024).

Preity, A. K., Bhandari & Shahnawazuddin, S. Automated computationally intelligent methods for ocular vessel segmentation and disease detection: a review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 31 (2), 701–724 (2024).

Mistry, J. & Ramakrishnan, R. The Automated Eye Cancer Detection through Machine Learning and Image Analysis in Healthcare. J. Xidian Univ.17 (8), 763 (2023).

Hoover, A. & Goldbaum, M. Locating the optic nerve in a retinal image using the fuzzy convergence of the blood vessels. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 22 (8), 951–958 (2003).

Welfer, D. et al. Segmentation of the optic disk in color eye fundus images using an adaptive morphological approach. Comput. Biol. Med. 40 (2), 124–137 (2010).

Youssif, A. A. H. A. R., Ghalwash, A. Z. & Ghoneim, A. A. S. A. R. Optic disc detection from normalized digital fundus images by means of a vessels’ direction matched filter. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 27 (1), 11–18 (2007).

Muangnak, N., Aimmanee, P. & Makhanov, S. Automatic optic disk detection in retinal images using hybrid vessel phase portrait analysis. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 56, 583–598 (2018).

Meng, X. et al. Fast and effective optic disk localization based on convolutional neural network. Neurocomputing. 312, 285–295 (2018).

Reza, M. N. Automatic detection of optic disc in color fundus retinal images using circle operator. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control. 45, 274–283 (2018).

Lu, S. & Lim, J. H. Automatic optic disc detection from retinal images by a line operator. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 58 (1), 88–94 (2010).

Zou, B., Chen, C., Zhu, C., Duan, X. & Chen, Z. Classified optic disc localization algorithm based on verification model. Comput. Graph. 70, 281–287 (2018).

Ramakanth, S. A. & Babu, R. V. Approximate nearest neighbour field based optic disk detection. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 38 (1), 49–56 (2014).

Rahebi, J. & Hardalaç, F. A new approach to optic disc detection in human retinal images using the firefly algorithm. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 54, 453–461 (2016).

Bharkad, S. Automatic segmentation of optic disk in retinal images. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control. 31, 483–498 (2017).

Walter, T., Klein, J. C., Massin, P. & Erginay, A. A contribution of image processing to the diagnosis of diabetic retinopathy-detection of exudates in color fundus images of the human retina. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 21 (10), 1236–1243 (2002).

Seo, J. M., Kim, K. K., Kim, J. H., Park, K. S. & Chung, H. Measurement of ocular torsion using digital fundus image. In The 26th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, vol. 1 1711–1713 (2004).

Stapor, K., Świtonski, A., Chrástek, R. & Michelson, G. Segmentation of fundus eye images using methods of mathematical morphology for glaucoma diagnosis. In Computational Science-ICCS 2004: 4th International Conference, Kraków, Poland, June 6–9, Proceedings, Part IV 4, 2004 41–48 (2004).

Kande, G. B., Subbaiah, P. V. & Savithri, T. S. Segmentation of exudates and optic disk in retinal images. In Sixth Indian Conference on Computer Vision, Graphics & Image Processing, 2008 535–542 (2008).

Lupascu, C. A., Tegolo, D. & Di Rosa, L. Automated detection of optic disc location in retinal images. In 21st IEEE International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems, 2008 17–22 (2008).

Morales, S., Naranjo, V., Angulo, J. & Alcañiz, M. Automatic detection of optic disc based on PCA and mathematical morphology. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 32 (4), 786–796 (2013).

Salazar-Gonzalez, A., Kaba, D., Li, Y. & Liu, X. Segmentation of the blood vessels and optic disk in retinal images. IEEE J. Biomed. Heal Inf. 18 (6), 1874–1886 (2014).

Tan, J. H., Acharya, U. R., Bhandary, S. V., Chua, K. C. & Sivaprasad, S. Segmentation of optic disc, fovea and retinal vasculature using a single convolutional neural network. J. Comput. Sci.20, 70–79 (2017).

Vyas, A. H. & Khanduja, V. A survey on automated eye disease detection using computer vision based techniques. In IEEE Pune Section International Conference (PuneCon), 2021 1–6 (2021).

Abbas, Q., Qureshi, I., Yan, J. & Shaheed, K. Machine learning methods for diagnosis of eye-related diseases: a systematic review study based on ophthalmic imaging modalities. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng.29 (6), 3861–3918 (2022).

Galveia, J. N., Travassos, A., Quadros, F. A. & da Silva Cruz, L. A. Computer aided diagnosis in ophthalmology: deep learning applications. Classif. BioApps Autom. Decis. Mak. 263–293, (2018).

Staal, J., Abràmoff, M. D., Niemeijer, M., Viergever, M. A. & Van Ginneken, B. Ridge-based vessel segmentation in color images of the retina. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 23 (4), 501–509 (2004).

Yaghoubi, E., Yaghoubi, E., Khamees, A., Razmi, D. & Lu, T. A systematic review and meta-analysis of machine learning, deep learning, and ensemble learning approaches in predicting EV charging behavior. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 135, 108789 (2024).

Yu, S., Xiao, D. & Kanagasingam, Y. Machine learning based automatic neovascularization detection on optic disc region. IEEE J. Biomed. Heal Inf. 22 (3), 886–894 (2017).

Fu, H. et al. Joint optic disc and cup segmentation based on multi-label deep network and polar transformation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 37 (7), 1597–1605 (2018).

Singh, L. K., Khanna, M., Thawkar, S. & Singh, R. Nature-inspired computing and machine learning based classification approach for glaucoma in retinal fundus images. Multimed Tools Appl. 82 (27), 42851–42899 (2023).

Singh, L. K. & Garg, H. Detection of glaucoma in retinal fundus images using fast fuzzy C means clustering approach. In International conference on computing, communication, and intelligent systems (ICCCIS), 2019 397–403 (2019).

Singh, L. K., Garg, H. & Khanna, M. An IoT based predictive modeling for Glaucoma detection in optical coherence tomography images using hybrid genetic algorithm. Multimed Tools Appl. 81, 26 (2022).

Singh, L. K., Khanna, M. & Thawkar, S. A novel hybrid robust architecture for automatic screening of glaucoma using fundus photos, built on feature selection and machine learning-nature driven computing. Expert Syst. 39 (10), e13069 (2022).

Singh, L. K. & Garg, H. Detection of glaucoma in retinal images based on multiobjective approach. Int. J. Appl. Evol. Comput. 11 (2), 15–27 (2020).

Yaghoubi, E., Yaghoubi, E., Khamees, A. & Vakili, A. H. A systematic review and meta-analysis of artificial neural network, machine learning, deep learning, and ensemble learning approaches in field of geotechnical engineering. Neural Comput. Appl. 36, 12655–12699 (2024).

Gulshan, V. et al. Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for detection of diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs. Jama. 316(22), 2402–2410 (2016).

Ting, D. S. W. et al. Development and validation of a deep learning system for diabetic retinopathy and related eye diseases using retinal images from multiethnic populations with diabetes. Jama. 318 (22), 2211–2223 (2017).

Zhang, L. & Lim, C. P. Intelligent optic disc segmentation using improved particle swarm optimization and evolving ensemble models. Appl. Soft Comput. 92, 106328 (2020).

Abdullah, A. S., Özok, Y. E. & Rahebi, J. A novel method for retinal optic disc detection using bat meta-heuristic algorithm. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 56, 2015–2024 (2018).

Pruthi, J., Khanna, K. & Arora, S. Optic Cup segmentation from retinal fundus images using Glowworm Swarm optimization for glaucoma detection. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control. 60, 102004 (2020).

Zaaboub, N., Sandid, F., Douik, A. & Solaiman, B. Optic disc detection and segmentation using saliency mask in retinal fundus images. Comput. Biol. Med. 150, 106067 (2022).

Kauppi, T. et al. The diaretdb1 diabetic retinopathy database and evaluation protocol. BMVC. 1(1), 10 (2007).

Carmona, E. J., Rincón, M., García-Feijoó, J. & Martínez-de-la-Casa, J. M. Identification of the optic nerve head with genetic algorithms. Artif. Intell. Med. 43 (3), 243–259 (2008).

Roychowdhury, S., Koozekanani, D. D., Kuchinka, S. N. & Parhi, K. K. Optic disc boundary and vessel origin segmentation of fundus images. IEEE J. Biomed. Heal Inf. 20 (6), 1562–1574 (2015).

Welfer, D., Scharcanski, J. & Marinho, D. R. A morphologic two-stage approach for automated optic disk detection in color eye fundus images. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 34 (5), 476–485 (2013).

Abdullah, M., Fraz, M. M. & Barman, S. A. Localization and segmentation of optic disc in retinal images using circular Hough transform and grow-cut algorithm. PeerJ. 4, 2016 (2003).

Marin, D., Gegundez-Arias, M. E., Suero, A. & Bravo, J. M. Obtaining optic disc center and pixel region by automatic thresholding methods on morphologically processed fundus images. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 118 (2), 173–185 (2015).

Funding

This research is part of the TIC251-G-FEDER project, funded by ERDF/EU.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Azhar Faisal wrote the main manuscript text and prepared results. Jorge Munilla reviewed the manuscript and modified the paper. Javad Rahebi prepared results and discussionof the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Faisal, A., Munilla, J. & Rahebi, J. Detection of optic disc in human retinal images utilizing the Bitterling Fish Optimization (BFO) algorithm. Sci Rep 14, 25824 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76134-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76134-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

DB-SegNet: optimized framework for glaucoma detection and optic structure segmentation from retinal fundus images

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

A novel method for optic disc localization using fast circlet transform and Chan-Vese segmentation

Scientific Reports (2025)