Abstract

This study investigated the modification of polyethersulfone (PES) ultrafiltration membranes with TiO2 and Fe2O3–TiO2 nanoparticles to enhance their hydrophilicity and biofouling resistance against the marine microalgae Chlorella vulgaris. It is a common freshwater and marine microalga that readily forms biofilms on membrane surfaces, leading to significant flux decline and increased operational costs in ultrafiltration processes. The microalgae cells and their extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) adhere to the membrane surface, creating a dense fouling layer that impedes water permeation. The modified membranes were characterized using contact angle measurements, scanning electron microscopy, and pure water flux/resistance tests. Short-term ultrafiltration experiments evaluated the membranes’ antifouling performance by measuring flux decline, flux recovery ratio, and relative flux reduction during C. vulgaris filtration. The TiO2 membrane showed improved hydrophilicity and antifouling over the pristine PES membrane, while the Fe2O3–TiO2 nanocomposite membrane exhibited the best performance. It reduced the water contact angle and showed only a 5% relative flux reduction compared to 60% for the pristine membrane. SEM images confirmed reduced microalgal deposition on the nanocomposite surface. Long-term tests with microalgal cells under dark and visible light conditions in saline water further assessed the membranes’ biofouling resistance. The Fe2O3–TiO2 membrane maintained 59 L/m2 h water flux under visible light after immersion in the microalgal solution, outperforming the pristine (38 L/m2 h) and TiO2 (52 L/m2 h) membranes. This superior antifouling was attributed to photocatalytic generation of reactive oxygen species inhibiting microalgal adhesion. This study demonstrates a promising strategy for mitigating biofouling in membrane-based water treatment and desalination processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Membrane ultrafiltration (UF) is extensively employed across various industries, including food, pharmaceutical, biotechnology, water desalination, and wastewater treatment, to separate diverse compounds1. UF is also considered a crucial pretreatment step for seawater reverse osmosis (SWRO) plants, acting as a barrier against suspended solids, microorganisms, and oil-emulsified water2. However, a significant challenge associated with membrane technology is membrane biofouling, which arises from the attachment and proliferation of microorganisms, such as algae and bacteria, on the membrane surface3,4. The formation of biofilms not only reduces the lifetime and capacity of water treatment systems but also increases pressure drop, consequently leading to higher operation and maintenance costs5. It is estimated that biofouling can account for up to 45% of the total operating costs in membrane systems and contribute to increased energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions, thereby impacting both the economic viability and environmental sustainability of these technologies6. Among the various microorganisms that contribute to biofouling, the green microalgae Chlorella vulgaris is of particular concern. Its prevalence in freshwater and marine environments, coupled with its ability to form dense biofilms on surfaces, makes it an ideal model organism for biofouling studies7. Moreover, C. vulgaris blooms are common in nutrient-rich waters and can lead to severe operational issues in desalination plants and water treatment facilities8.

Polyethersulfone (PES) is widely used in the production of UF membranes due to its superior mechanical strength, thermal stability, and chemical resistance9. Nonetheless, the hydrophobic nature of PES renders it susceptible to biofilm formation when the membrane surface comes into contact with fouling solutions10. The adsorption and deposition of organic materials and microorganisms on the PES membrane’s surface and within its pores result in a significant decline in water flux, thereby limiting the practical application of PES as a UF membrane11.

To enhance membrane hydrophilicity and improve the resistance of PES membranes against biofouling, researchers have explored various surface modification techniques, including coating, grafting, and different functionalization methods12,13. In recent years, several studies have investigated modifying membrane surfaces using inorganic nanoparticles to enhance separation performance and membrane resistance against fouling. Membranes modified with nanoparticles have demonstrated the ability to decrease adhesion and prevent the attachment of organic matter, subsequently reducing biofouling. Nanoparticles such as carbon nanotubes, Al2O3, zeolites, SiO2, ZnO, ZrO2, Ag, and TiO2 have been utilized for the modification of different membranes14. Among these nanoparticles, TiO2 has garnered significant attention due to its chemical and thermal stability, antimicrobial properties, high hydrophilicity, and photocatalytic activity15,16. It has been found that the modification of water filtration membranes with TiO2 nanoparticles enhances flux, fouling resistance, and contaminant removal17. However, TiO2 alone has been limited by its relatively low photocatalytic activity under visible light due to its relatively high band gap energy (3.2 eV). Several studies have demonstrated that blending TiO2 with other inorganic nanomaterials can enhance its photocatalytic activity under visible light, helping to reduce membrane fouling18,19. Fe2O3, a low-cost and stable material, possesses a low band gap (2.2 eV) and high visible-light absorption, making it a suitable candidate for modifying TiO2 properties and broadening the light absorption range20.

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in developing visible-light-active photocatalytic membranes for biofouling control and water treatment applications21,22,23. Several studies have demonstrated the potential of TiO2-based nanocomposites, especially those incorporating Fe2O3, in enhancing the photocatalytic activity and antifouling properties of membranes under visible light irradiation24,25. However, most of these studies have focused on short-term experiments or model foulants under non-saline water conditions, and there is a need for more comprehensive investigations on the long-term performance and stability of these nanocomposite-modified membranes under realistic conditions, such as the presence of biofilm-forming microorganisms and seawater salinity.

In this study, we investigated the modification of PES ultrafiltration membranes through the deposition of TiO2 and Fe2O3-TiO2 nanoparticles, aiming to enhance their resistance to biofouling. We systematically evaluated the performance of these modified membranes under realistic operational conditions, specifically examining the effects of visible light irradiation during both short-term and long-term ultrafiltration processes involving the biofilm-forming microalgae C. vulgaris. The modified membranes were characterized using a range of analytical techniques, allowing for a comprehensive assessment of their performance metrics and biofouling properties. The strategic deposition of nanoparticles on the membrane surface was designed to improve hydrophilicity and photocatalytic activity, thereby mitigating biofouling potential. A key innovation of our research is the examination of both short term and long-term performance of TiO2 and Fe2O3-TiO2 nanocomposite-modified PES ultrafiltration membranes under conditions that closely mimic realistic operational environments. The modification of the membrane is expected to improve its overall antifouling efficacy under ambient lighting conditions. By exposing the modified membranes to seawater salinity and visible light, we obtained critical insights into their long-term performance and biofouling resistance. This study not only contributes to the understanding of nanocomposite-modified membranes but also holds significant implications for their application in real-world water treatment scenarios. The graphical abstract of the study has been shown in Fig. S1 (Please see the Supplementary File).

Materials and methods

Materials

The commercial flat sheet UF membrane used in this study was the NanostoneTM PS35, manufactured by Nanosep Membranes Co. (India). The membrane had a molecular weight cut-off of 20 kDalton and was intended for water pretreatment applications. The biofilm-forming microalgae species C. vulgaris, obtained from the Persian Type Culture Collection (IROST, Iran), was used for the biofouling studies. All chemicals and reagents utilized in the experiments were of analytical grade and procured from Sigma-Aldrich Supplementary (Germany).

Synthesis of Fe2O3–TiO2 nanocomposite

Titanium dioxide (TiO2) and iron(III) oxide (Fe2O3)-doped TiO2 nanoparticles were synthesized using the ultrasonic co-precipitation method. The Fe2O3-TiO2 nanocomposites contained 2.5 wt% of Fe2O3. These nanoparticles were employed to modify the surface of an ultrafiltration (UF) membrane.

Titanium tetrachloride (TiCl4) was used as the titanium precursor. A 0.5 M TiCl4 solution was prepared by slowly adding pure TiCl4 to cold deionized water under vigorous stirring. Diluted ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH) solution was gradually added to the TiCl4 solution under ultrasound irradiation and continuous stirring at 80 °C for 2 h, until a pH of 9 was reached. The synthesized TiO2 nanoparticles were then centrifuged, washed repeatedly with deionized water to remove impurities and neutralize the solution, and dried in a vacuum oven at 100 °C overnight. To incorporate Fe2O3 into the TiO2 matrix, a TiO2 colloidal suspension at pH 7 was added to a pre-calculated amount of sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) aqueous solution under ultrasonication at 80 °C. Iron(III) nitrate nonahydrate (Fe(NO3)3·9H2O) was dissolved in deionized water and added dropwise to the TiO2 suspension under continuous ultrasonication. The mixture was stirred for an additional 2 h to ensure complete incorporation of Fe2O3 into the TiO2 lattice. The resulting Fe2O3-TiO2 nanocomposites were centrifuged, washed repeatedly with deionized water to remove residual salts, and dried in a vacuum oven at 100 °C overnight. The structural, morphological, and optical properties of the synthesized TiO2 and Fe2O3-TiO2 nanoparticles were characterized using various techniques, such as X-ray diffraction (XRD), Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area analysis, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), selected area electron diffraction (SAED), energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy, and diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS), as reported in our previous work26.

The resultant band gap of synthesized Fe2O3-TiO2 nanocomposite was measured as 2.9 eV. The is typically lower than that of pure TiO2 (3.25 eV), which enables visible light absorption and photocatalytic activity of the nanocomposite26.

Membrane modification

The fabrication of nanostructured surface-functionalized UF membranes was achieved through the dip coating method. The dip coating method was used for membrane modification due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, good adhesion between the nanoparticles and the membrane surface, and ability to produce uniform coatings. Dilute suspensions of TiO2 and Fe2O3-TiO2 nanoparticles, with a concentration of 0.3 g/L, were prepared in distilled water. The choice of this concentration for the nanoparticle suspensions was based on previous research, balance between surface coverage and pore blocking, and nanoparticle dispersion stability. To disperse any aggregates, the suspensions were subjected to sonication for 5 min and thoroughly stirred before the functionalization process. The pristine UF membranes were immersed in the nanoparticle suspensions for 15 min, considered the optimum time according to previous studies27. Subsequently, the functionalized membranes were rinsed with pure water to remove unbound nanoparticles. To activate the self-cleaning property and enhance hydrophilicity, the membranes were directly exposed to a 60 W UV lamp for 15 min28. The prepared membranes were stored in pure water at 4 °C prior to characterization and utilization. The UF membranes modified with TiO2 and Fe2O3-TiO2 nanoparticles are denoted as UF-T and UF-FT, respectively.

Membrane characterization

The hydrophilicity of the pristine UF, UF-T, and UF-FT membranes was evaluated to investigate the wetting properties of the membranes. A Dataphysics plus OCA 15 contact angle device was employed to measure the contact angle between deionized water droplets and the membrane surface, thereby assessing the membrane’s hydrophilicity. The average value of three randomly selected points was reported as the representative contact angle measurement.

The surface morphology of the membranes was examined using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM Mira III-TESCAN, Czech Republic) operating at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. To render the membrane samples electrically conductive, a thin layer of platinum was sputter-coated onto their surface before imaging. The performance stability of the UF-T and UF-FT membranes was evaluated through the flux retention ratio during long-term testing. This ratio was calculated as the percentage of flux retained over an extended period compared to the initial flux29.

Microalgal culture and saline water preparation

Batch cultures of the microalgae species C. vulgaris were cultivated in Erlenmeyer flasks containing freshwater enriched with essential nutrients and minerals30. C. vulgaris cultures were maintained in the growth medium for 12 days under continuous illumination (light intensity: 136 µmol photons/ m2.s) at 25 °C with constant aeration. Cultures were harvested during the exponential growth phase, when cell concentrations reached approximately 106 cells/L. The flasks were continuously shaken and exposed to light irradiation31. The algal cell number was determined by direct cell counting under a microscope using a Neubauer® counting slide. The C. vulgaris cells were subsequently diluted with freshwater to achieve an algal cell concentration of 105 cells/L and then transferred into the feed tank of the UF membrane testing apparatus. This concentration is comparable to that observed during algal blooms32. To test the membranes in a saline environment, synthetic seawater with a salinity of 35 g/L was prepared in the feed tank by adding the following inorganic salts: NaCl (28.1 g/L), MgCl2.2H2O (4.8 g/L), MgSO4.7H2O (3.5 g/L), CaCl2.2H2O (1.6 g/L), KCl (0.77 g/L), and NaHCO3 (0.11 g/L)33.

Ultrafiltration setup and flux measurements

The UF apparatus depicted in Fig. 1 was employed to conduct experiments evaluating membrane flux and fouling behavior. For all experiments, flat sheet membranes with dimensions of 2.2 cm × 7.2 cm were placed inside a transparent cross-flow cell. The temperature of the feed tank was maintained at 25 °C using a water jacket. Biofouling experiments were carried out in freshwater and saline water environments.

Before each experiment, the membranes were pressurized with pure water at a transmembrane pressure (TMP) of 300 kPa for 30 min. Subsequently, the upstream pressure was reduced, and the experiment was conducted at a TMP of 200 kPa and a cross-flow velocity of 0.75 m/s for 120 min. The permeate flux was calculated every 15 min using Eq. 1:

Where J is the permeate flux (L/m².h), V is the permeated water volume (L), A is the surface area of the membrane in the cell (m²), and t is the time (h).

To evaluate the biofouling resistance of the pristine and modified membranes against microalgal cells, the flux recovery ratio (FRR) of the membranes was calculated as Eq. 217:

Where Jwuf (L/m².h) and Jw (L/m².h) are the pure water flux values prior to and after the filtration of the C. vulgaris aqueous suspension, respectively. Initially, the pure water flux of the membrane was measured (Jwuf). Subsequently, the microalgae-containing water was used to induce fouling on the membrane surface. Finally, the pure water flux was measured again (Jw).

The relative flux reduction (RFR), which indicates the changes in membrane flux and the resistance of membranes against biofouling, was also calculated using the following Eq. 3:

Where Jp (L/m²·h) and Jw (L/m²·h) are the permeation fluxes of the C. vulgaris-containing solution and pure water, respectively.

For these measurements, three repetitions were performed for each experimental condition. This replication helps to account for any variations and provides a more robust assessment of the membranes’ performance. Additionally, for each experimental run, a new membrane sample was used.

The evaluation of the pristine UF, UF-T, and UF-FT membranes was performed using the ultrafiltration apparatus under dark conditions. Since the FT nanoparticles could be activated with visible light, the UF-FT membrane was evaluated under visible light irradiation of 60 W/m². The membrane activation was not performed under UV light due to economic and health concerns. The RFR provides a quantitative measure of the extent of flux decline caused by biofouling, with a higher value indicating more significant flux reduction and, consequently, more severe biofouling. By comparing the RFR values of the pristine and modified membranes under different lighting conditions, the effectiveness of the nanoparticle embedment and visible light irradiation in mitigating biofouling could be assessed.

Long-term immersion tests

Long-term experiments were conducted to investigate the anti-biofouling properties of the modified membranes. The pristine UF, UF-T, and UF-FT membranes were immersed in water with a salinity of 35 g/L containing C. vulgaris cells at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/L. The immersion was conducted at ambient temperature (25 °C) under dark conditions for 120 min. Additionally, another UF-FT membrane was subjected to the same conditions but under visible light irradiation of 60 W/m2 to understand the photocatalytic effect of the FT nanoparticles on biofouling development. After 120 min, the membranes were removed and placed in a UF testing cell to measure the pure water flux and evaluate their anti-biofouling behavior. The total resistance of the membrane against water permeation (Rt, m− 1) was calculated using Eq. 4:

Where ΔP is the transmembrane pressure (Pa), µ (Pa·s) is the viscosity, and J (m3/m2·s) is the permeate flux. The total membrane resistance comprises both fouling resistance and intrinsic membrane resistance. The fouling resistance arises from the formation of a layer of deposited microalgae cells on the membrane’s surface. It is to be noted that all analyses were performed in triplicate, the average values, and standard deviation were reported as the final results.

Results and discussion

Properties of membranes

Pure water permeability and resistance

Table 1 presents the pure water flux and total resistance (Rt) values for the pristine UF membrane and the membranes modified with TiO2 (UF-T) and Fe2O3-TiO2 (UF-FT) nanoparticles. The pristine UF membrane exhibited the highest pure water flux of 87.12 L/m2·h, whereas the UF-T membrane had the lowest flux of 64.39 L/m2·h. The UF-FT membrane showed an intermediate flux of 79.55 L/m2·h.

The total resistance (Rt) values follow an opposite trend, with the UF-T membrane having the highest resistance of 12.7 × 1012 m− 1, followed by the UF-FT membrane (10.3 × 1012 m− 1), and the pristine UF membrane exhibiting the lowest resistance of 9.4 × 1012 m− 1. The modified membranes showed lower flux and higher resistance to water permeation (Rt), even though they had a lower contact angle (see Fig. 4). This can be explained by the deposition of nanoparticles on the membrane surface, which likely increased the resistance to water flow. These observations align with findings in the literature29,34,35,36. Jigar et al.29 noted that the performance of TiO2-modified PVDF membranes decreased as the TiO2 loading increased, reinforcing our results. Cui et al.34 observed a decrease in pure water flux and an increase in resistance for polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes modified with SiO2 nanoparticles. Similarly, Razmjou et al.36 reported a reduction in pure water flux for PES membranes modified with TiO2 nanoparticles, attributing this decline to the increased resistance caused by nanoparticle deposition. It is noteworthy that the UF-FT membrane exhibited a higher pure water flux and lower resistance compared to the UF-T membrane. This behavior could be attributed to the incorporation of Fe2O3 into the TiO2 nanoparticles, which may have influenced the surface properties and pore structure of the modified membrane.

The observed improvement in UF-FT water flux can be attributed to the increased hydrophilicity of the UF-FT membranes by incorporation of Fe2O3 into TiO2 nanoparticles, as illustrated by the contact angle measurements shown in Fig. 4. The UF-FT membrane modified with Fe2O3-TiO2 nanoparticles demonstrated the lowest contact angle, indicating that it possesses the highest hydrophilicity among the three membranes evaluated. This increased hydrophilicity facilitates better water permeation, leading to improved water flux through the membrane. The incorporation of Fe₂O₃-TiO₂ nanocomposites may result in a more homogeneous distribution on the membrane surface, potentially yielding a more uniform and less restrictive coating compared to TiO₂ alone37. Furthermore, the Fe₂O₃-TiO₂ nanocomposites may exhibit distinct interactions with the polyethersulfone (PES) membrane matrix during the coating process, which could facilitate the development of a more advantageous pore structure. This enhanced pore configuration may promote improved water permeation while preserving filtration efficiency38. Additionally, the introduction of Fe₂O₃ may modify the surface charge of the nanoparticles, which could influence their interactions with water molecules and foulants, thereby enhancing flux and mitigating fouling39.

Permeate flux and antifouling performance

Figure 2 depicts the time-dependent behavior of the permeate flux for the pristine UF, UF-T, and UF-FT membranes during the ultrafiltration of a C. vulgaris solution over 120 min. The flux profiles provide valuable insights into the membrane fouling propensity and the effectiveness of nanoparticle modifications in mitigating biofouling. For the pristine UF membrane, a rapid and significant decline in permeate flux is observed within the first 30 min of operation. This sharp flux decay can be attributed to the accumulation and deposition of microalgal cells and their extracellular organic matter on the hydrophobic PES membrane surface, leading to severe biofouling and increased hydraulic resistance. In addition, it exhibits a substantial flux decline throughout the 120-min filtration experiment, with the permeate flux decreasing from an initial value of approximately 95 L/m2·h to around 34 L/m2·h by the end of the experiment.

In contrast, the UF-T and UF-FT membranes show improved flux stability and reduced flux decline compared to the pristine membrane. The flux retention percentages, which serve as indicators of stability, were found to be 95.0% for the UF-FT membrane and 93.3% for the UF-T membrane. These results suggest that the UF-FT membrane exhibits greater stability, likely due to a stronger interaction between the Fe2O3-TiO2 nanoparticles and the PES polymer. The UF-T membrane maintains a relatively higher flux, ranging from around 68 L/m2·h to 56 L/m2·h, while the UF-FT membrane exhibits the highest flux values, declining from approximately 80 L/m2·h to 76 L/m2·h over the course of the experiment. These observations suggest that modifying the UF membranes with TiO2 and Fe2O3-TiO2 nanoparticles enhances their resistance to biofouling caused by the microalgal cells. The improved antifouling performance can be attributed to the increased hydrophilicity of the modified membranes, as demonstrated by the contact angle measurements in Fig. 4. Hydrophilic surfaces tend to repel foulants and prevent their adhesion, thereby mitigating flux decline. The superior antifouling behavior of the UF-FT membrane compared to the UF-T membrane can be attributed to the incorporation of Fe2O3 into the TiO2 nanoparticles. The presence of Fe2O3 may have further enhanced the hydrophilicity and surface properties of the membrane, leading to improved biofouling resistance. These findings are consistent with previous studies reported in the literature. Rahimpour et al.27 observed improved flux recovery and reduced fouling for PES membranes modified with TiO2 nanoparticles during the filtration of humic acid solutions. Moghimifar et al.14 also reported enhanced antifouling properties for PES ultrafiltration membranes modified with TiO2 nanoparticles during the filtration of bovine serum albumin (BSA) solutions.

Figure 3 presents two critical parameters, the flux recovery ratio (FRR) and relative flux reduction (RFR), which provide quantitative insights into the extent of biofouling and the effectiveness of the nanoparticle modifications in mitigating fouling during the ultrafiltration of C. vulgaris solution. The FRR reflects the membrane’s ability to recover its initial pure water flux after the fouling experiment. At the same time, the RFR indicates the degree of flux decline caused by biofouling during the experiment. For the pristine UF membrane, the FRR is approximately 42%, suggesting that only 42% of the original pure water flux could be recovered after ultrafiltration of the microalgal solution. This implies significant and irreversible fouling on the membrane surface. Furthermore, the RFR for the pristine membrane is around 60%, indicating a substantial reduction in the permeate flux during the fouling experiment, corroborating the severe flux decline observed in Fig. 2. The UF-T membrane modified with TiO2 nanoparticles exhibits an improved FRR of around 92%, demonstrating better fouling reversibility compared to the pristine membrane. Additionally, the RFR is reduced to around 12%, signifying a lower extent of flux decline during the ultrafiltration process. These improvements can be attributed to the enhanced hydrophilicity and potential photocatalytic effects of the TiO2 nanoparticles, which inhibit the adhesion and growth of microalgal cells on the membrane surface. The UF-FT membrane, functionalized with Fe2O3-TiO2 composite nanoparticles, displays the most promising antifouling performance, with an FRR of approximately 95% and an RFR of only around 5%. These values indicate excellent fouling reversibility and minimal flux reduction during the ultrafiltration process, highlighting the synergistic effects of the Fe2O3 and TiO2 components in mitigating biofouling. The high FRR and low RFR values achieved with the modified membranes suggest that such nanoparticle-functionalized membranes could be highly effective in maintaining stable long-term operation and reducing the frequency of membrane cleaning or replacement, ultimately leading to significant cost savings and improved sustainability in various water treatment and biotechnology applications. These findings are well supported by recent studies on nanoparticle-modified membranes for biofouling control. Baniamerian et al.26 demonstrated the anti-algal activity of Fe2O3-TiO2 nanoparticles on C. vulgaris under visible light irradiation, attributing the observed effects to the photocatalytic generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Ahmad et al.17 reported improved flux and photodegradation performance for a TiO2-coated Al2O3 membrane under visible light irradiation, highlighting the potential of photocatalytic membranes for enhanced antifouling properties.

Surface wettability and hydrophilicity

The contact angle measures of the wettability or hydrophilicity of a surface, with lower values indicating higher hydrophilicity. Figure 4 shows that the pristine UF membrane exhibits a relatively high contact angle of approximately 67°, indicating a moderately hydrophobic surface. This behavior is expected for PES membranes, which are inherently hydrophobic due to their chemical structure. Upon modification with TiO2 nanoparticles, the UF-T membrane reduces contact angle to around 63°, suggesting an enhancement in surface hydrophilicity. This improvement is attributed to the hydrophilic nature of TiO2 nanoparticles, which can increase the overall surface energy and wettability of the membrane. The UF-FT membrane, modified with Fe2O3-TiO2 nanoparticles, exhibits the lowest contact angle of approximately 58°, indicating the highest hydrophilicity among the three membranes studied. The further reduction compared to UF-T can be ascribed to the synergistic effects of the hydrophilic TiO2 and Fe2O3 components. Iron oxide nanoparticles exhibit good hydrophilicity due to the presence of hydroxyl groups on their surface. While the contact angle reductions for the modified membranes are modest, it is essential to note that even a small decrease in contact angle can lead to substantial improvement in anti-fouling properties. These findings are consistent with previous studies reported in the literature. Guan observed a decrease in contact angle and increased hydrophilicity for TiO2/SiO2 films, attributing this behavior to the photocatalytic activity and self-cleaning effect of TiO240. Razmjou et al.36 also reported a reduction in contact angle for PES membranes modified with TiO2 nanoparticles, indicating enhanced hydrophilicity. The improved hydrophilicity of the modified membranes is expected to have a positive impact on their antifouling properties. Hydrophilic surfaces tend to attract water molecules, forming a hydration layer that can repel foulants and prevent their adhesion to the membrane surface. This phenomenon can potentially mitigate biofouling and enhance the overall performance and lifespan of the membranes.

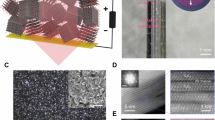

Surface morphology and fouling layer

Figure 5 presents scanning electron microscope (SEM) images that provide visual insights into the extent of biofouling on the pristine UF membrane (Fig. 5A) and the UF-FT membrane modified with Fe2O3-TiO2 composite nanoparticles (Fig. 5B) after ultrafiltration of a C. vulgaris solution in seawater for 120 min. The SEM image of the pristine UF membrane (Fig. 5A) reveals a dense layer of fouling material covering the entire membrane surface. The deposited material appears to be composed of microalgal cells and their extracellular organic matter, forming a biofilm-like structure. This severe biofouling can be attributed to the hydrophobic nature of the unmodified PES membrane, which promotes the adhesion and accumulation of fouling species, leading to pore blockage and flux decline, as observed in Fig. 2. In contrast, the SEM image of the UF-FT membrane (Fig. 5B) shows a significantly cleaner surface with minimal fouling deposits. Only a few scattered microalgal cells and some organic matter are visible, suggesting that the Fe2O3-TiO2 nanoparticle modification effectively mitigated biofouling during the ultrafiltration process. This improved antifouling performance is attributed to the enhanced hydrophilicity and potential photocatalytic activity of the composite nanoparticles, which inhibit the adhesion and growth of microalgal cells on the membrane surface. These visual observations are consistent with the flux data presented in Figs. 2 and 3, where the UF-FT membrane exhibited significantly better flux performance and lower flux reduction than the pristine membrane during the ultrafiltration of the C. vulgaris solution. The SEM results are further supported by several recent studies investigating nanoparticle-modified membranes for biofouling mitigation. Vander Wiel et al.35 employed multi-pixel photon counters to characterize the surface interaction and adhesion of Chlorella species on different surfaces, demonstrating the influence of surface properties on biofouling behavior. Nejati et al.2 investigated biofouling in seawater reverse osmosis membranes and found that surface modification strategies, such as coating with nanoparticles, can effectively mitigate biofouling propensity. The SEM images in Fig. 5, along with the supporting literature, provide visual evidence of the effectiveness of nanoparticle modifications, particularly with composite nanoparticles like Fe2O3-TiO2, in mitigating biofouling on ultrafiltration membranes. Maintaining a clean membrane surface by inhibiting the adhesion and growth of fouling species is crucial for ensuring stable long-term operation and minimizing the frequency of membrane cleaning or replacement. This ultimately leads to improved process efficiency and reduced operational costs in various water treatment and biotechnology applications.

SEM images of (A) pristine UF membrane and (B) UF-FT membrane, both obtained after ultrafiltration of seawater containing C. vulgaris. The images show the fouling layer consisting of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) and organic matter, with minimal presence of intact microalgal cells due to the cross-flow configuration employed in the experiments.

Long-term antifouling stability in saline water under dark and visible light irradiation

Figure 6 presents the results of a long-term biofouling experiment, where the pristine UF, UF-T, and UF-FT membranes were immersed in a saline solution containing C. vulgaris microalgal cells for 120 min. The pure water flux of the membranes was measured after this immersion period to evaluate their resistance to biofouling under different lighting conditions (dark and visible light irradiation for the UF-FT membrane).

The experiments involved immersing the membranes in saline water (35 g/L) containing C. vulgaris cells (5 × 10⁵ cells/L) for 120 min under dark conditions. Additionally, one UF-FT membrane was exposed to visible light irradiation (60 W/m²) during the immersion period. After 120 min, the pure water flux of the membranes was measured to evaluate their biofouling resistance. The results show that the pristine UF membrane experienced a flux decline, with a pure water flux of only 38 L/m²·h after the 120 min immersion. This reduction in flux indicates that the membrane surface was fouled by the microalgal cells, forming a dense biofilm that impeded water permeation. The UF-T membrane, modified with TiO2 nanoparticles, improved biofouling resistance, with a pure water flux of 52 L/m²·h. This enhancement can be attributed to the increased hydrophilicity and potential antimicrobial properties of TiO2 nanoparticles, which reduced the adhesion and growth of microalgal cells on the membrane surface. Notably, the UF-FT membrane under dark conditions exhibited a higher pure water flux of 57 L/m²·h, indicating superior biofouling resistance compared to the pristine UF and UF-T membranes. This improvement is likely due to the synergistic effect of TiO2 and Fe2O3 nanoparticles, which may have further enhanced the surface properties and antimicrobial activity of the membrane. The most significant finding, however, is the performance of the UF-FT membrane under visible light irradiation. This membrane maintained a remarkably high pure water flux of 59 L/m²·h after 120 min of immersion, demonstrating exceptional resistance to biofouling. The superior performance of the UF-FT membrane under visible light can be attributed to the photocatalytic activity of Fe2O3-TiO2 nanoparticles. As discussed in the introduction, incorporating Fe2O3 into TiO2 nanoparticles lowers the band gap energy and extends the light absorption range into the visible region. Under visible light irradiation, these nanoparticles generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) with strong antimicrobial properties26. The ROS can effectively inhibit the growth and adhesion of microalgal cells, thereby mitigating biofilm formation and maintaining high membrane permeability. These findings are consistent with recent publications in the field. For instance, a study by Magesan et al. reported that Fe2O3-TiO2 nanocomposite exhibited photodynamic activity and antibacterial properties against Escherichia coli under sunlight via ROS generation41. Similarly, the higher photocatalytic inactivation of E.coli in drinking water by Fe2O3-TiO2 nanocomposite compared to TiO2 and Fe2O3 nanoparticles was reported42. Alghamadi et al. demonstrated that Fe2O3-TiO2-incorporated nanocomposite film has a significant antimicrobial activity that can be used for food packaging43.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the effectiveness of modifying PES ultrafiltration membranes with Fe2O3-TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing biofouling resistance against the microalgae C. vulgaris. The nanoparticle embedment significantly improved membrane hydrophilicity, with the water contact angle decreasing from 67° for the pristine membrane to 58° for the Fe2O3-TiO2 modified membrane. During short-term ultrafiltration experiments, the Fe2O3-TiO2 modified membrane exhibited a relative flux reduction (RFR) of only 5% under dark conditions, compared to 60% for the unmodified PES membrane. Long-term experiments in saline water revealed that after 120 min of immersion, the Fe2O3-TiO2 membrane under visible light maintained the highest pure water flux of 59 L/m2·h, significantly outperforming the pristine membrane (38 L/m2·h). The photocatalytic generation of reactive oxygen species effectively mitigated biofilm formation on the modified membrane surface. This study highlights the promising potential of Fe2O3-TiO2 nanocomposite-functionalized membranes, coupled with visible light treatment, as an effective anti-biofouling strategy for ultrafiltration applications in seawater desalination and wastewater treatment. The long-term antifouling performance could lead to reduced membrane cleaning requirements and extended operational lifetimes, translating to significant cost savings and sustainability benefits.

Future research directions should focus on further optimizing the Fe2O3-TiO2 nanoparticle composition and loading to maximize antifouling performance while maintaining high water flux. Long-term studies (> 1000 h) under realistic operating conditions are recommended to assess the durability and stability of the nanoparticle coating. Additionally, investigating the impact of different water chemistries and organic matter compositions on the antifouling performance would provide valuable insights for practical applications. The potential for scaling up this technology should be explored, including cost-effective methods for large-scale membrane modification and integration into existing ultrafiltration systems. Further research is also needed to evaluate the environmental impact and potential release of nanoparticles during membrane operation and cleaning cycles. Finally, comparative studies with other emerging antifouling strategies, such as zwitterionic coatings or quorum quenching approaches, would help position this technology within the broader context of membrane biofouling control solutions.

Data availability

All data generated and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Saberi, S., Shamsabadi, A. A., Shahrooz, M., Sadeghi, M. & Soroush, M. Improving the transport and antifouling properties of poly (vinyl chloride) hollow-fiber ultrafiltration membranes by incorporating silica nanoparticles. ACS Omega. 3, 17439–17446 (2018).

Nejati, S., Mirbagheri, S. A., Warsinger, D. M. & Fazeli, M. Biofouling in seawater reverse osmosis (SWRO): Impact of module geometry and mitigation with ultrafiltration. J. Water Process. Eng. 29, 100782 (2019).

Nagaraj, V., Skillman, L., Li, D. & Ho, G. Review–Bacteria and their extracellular polymeric substances causing biofouling on seawater reverse osmosis desalination membranes. J. Environ. Manage. 223, 586–599 (2018).

Chiou, Y. T., Hsieh, M. L. & Yeh, H. H. Effect of algal extracellular polymer substances on UF membrane fouling. Desalination. 250, 648–652 (2010).

Armendáriz-Ontiveros, M. M., Álvarez-Sánchez, J., Dévora-Isiordia, G. E., García, A. & Weihs, G. A. F. Effect of seawater variability on endemic bacterial biofouling of a reverse osmosis membrane coated with iron nanoparticles (FeNPs). Chem. Eng. Sci. 223, 115753 (2020).

Giwa, A., Akther, N., Housani, A. A., Haris, S. & Hasan, S. W. Recent advances in humidification dehumidification (HDH) desalination process—Review. Chem. Eng. J. 367, 33–57 (2019). 2019.

Flemming, H. C. Biofouling in water systems–cases, causes and countermeasures. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 59, 629–640 (2002).

Liao, L., Yu, S., Deng, W., Zhu, Z. & Wang, X. Biofouling control: Bacterial quorum quenching versus chlorination in membrane biofouling. Desalination. 401, 125–132 (2017).

Boussu, K. et al. Characterization of commercial nanofiltration membranes and comparison with self-made polyethersulfone membranes. Desalination. 191, 245–253 (2006).

Barzegar, H., Zahed, M. A. & Vatanpour, V. Antibacterial and antifouling properties of Ag3PO4/GO nanocomposite blended polyethersulfone membrane applied in dye separation. J. Water Process. Eng. 38, 101638 (2020).

Prince, J. A., Bhuvana, S., Boodhoo, K. V. K., Anbharasi, V. & Singh, G. Synthesis and characterization of PEG-Ag immobilized PES hollow fiber ultrafiltration membranes with long lasting antifouling properties. J. Memb. Sci. 454, 538–548 (2014).

Zhu, L. J. et al. Hydrophilic and anti-fouling polyethersulfone ultrafiltration membranes with poly (2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) grafted silica nanoparticles as additive. J. Memb. Sci. 451, 157–168 (2014).

Leda, K. T., Takada, K. & Jiang, S. C. Surface modification of a microfiltration membrane for enhanced anti-biofouling capability in wastewater treatment process. J. Water Process. Eng. 26, 55–61 (2018).

Moghimifar, V., Raisi, A. & Aroujalian, A. Surface modification of polyethersulfone ultrafiltration membranes by corona plasma-assisted coating TiO2 nanoparticles. J. Memb. Sci. 461, 69–80 (2014).

Méricq, J. P., Mendret, J., Brosillon, S. & Faur, C. High performance PVDF-TiO2 membranes for water treatment. Chem. Eng. Sci. 123, 283–291 (2015).

He, J., Kumar, A., Khan, M. & Lo, I. M. C. Critical review of photocatalytic disinfection of bacteria: from noble metals-and carbon nanomaterials-TiO2 composites to challenges of water characteristics and strategic solutions. Sci. Total Environ. 143953 (2020).

Ahmad, R., Lee, C. S., Kim, J. H. & Kim, J. Partially coated TiO2 on Al2O3 membrane for high water flux and photodegradation by novel filtration strategy in photocatalytic membrane reactors. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 163, 138–148 (2020).

Sisay, E. J. et al. Visible-light-driven photocatalytic PVDF-TiO2/CNT/BiVO4 hybrid nanocomposite ultrafiltration membrane for dairy wastewater treatment. Chemosphere. 307, 135589 (2022).

Sisay, E. J. et al. Investigation of photocatalytic PVDF membranes containing inorganic nanoparticles for model dairy wastewater treatment. Membranes. 13, 656 (2023).

Uyguner-Demirel, C. S., Birben, C. N. & Bekbolet, M. A comprehensive review on the use of second generation TiO2 photocatalysts: microorganism inactivation. Chemosphere. 211, 420–448 (2018).

Kusworo, T. D., Budiyono, A. C. K. & Utomo, D. P. Photocatalytic nanohybrid membranes for highly efficient wastewater treatment: a comprehensive review. J. Environ. Manag. 317, 115357 (2022).

Jeong, E., Byun, J., Bayarkhuu, B. & Hong, S.W. Hydrophilic photocatalytic membrane via grafting conjugated polyelectrolyte for visible-light-driven biofouling control. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 282, 119587 (2021).

Shi, Y., Huang, J., Zeng, G. & Cheng, W. Hu. Photocatalytic membrane in water purification: is it stepping closer to be driven by visible light? J. Membrane Sci. 584, 364–392 (2019).

Fu, J. et al. Photocatalytic ultrafiltration membranes based on visible light responsive photocatalyst: A review. Desalin. Water Treat. 168, 42–55 (2019).

Tetteh, E. K., Rathilal, S., Asante-Sackey, D. & Noro Chollom, M. Prospects of synthesized magnetic TiO2-based membranes for wastewater treatment: A review. Materials. 14, 3524 (2021).

Baniamerian, H. et al. Photocatalytic inactivation of Vibrio fischeri using Fe2O3-TiO2-based nanoparticles. Environ. Res. 166, 497–506 (2018).

Rahimpour, A., Madaeni, S. S., Taheri, A. H. & Mansourpanah, Y. Coupling TiO2 nanoparticles with UV irradiation for modification of polyethersulfone ultrafiltration membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 313, 158–169 (2008).

Madaeni, S. S. & Ghaemi, N. Characterization of self-cleaning RO membranes coated with TiO2 particles under UV irradiation. J. Memb. Sci. 303, 221–233 (2007).

Jigar, E. et al. Filtration of BSA through TiO2 photocatalyst modified PVDF membranes. J. Desal Water Treat. 192, 392–399 (2020).

Van Wagenen, J., Holdt, S. L., De Francisci, D., Valverde-Pérez, B. & Plósz Angelidaki, I. Microplate-based method for high-throughput screening of microalgae growth potential. Bioresour Technol. 169, 566–572 (2014).

Baniamerian, H. et al. Anti-algal activity of Fe2O3–TiO2 photocatalyst on Chlorella vulgaris species under visible light irradiation. Chemosphere. 242, 125119 (2020).

Sathe, P., Myint, M. T. Z., Dobretsov, S. & Dutta, J. Removal and regrowth inhibition of microalgae using visible light photocatalysis with ZnO nanorods: A green technology. Sep. Purif. Technol. 162, 61–67 (2016).

Golzary, A., Imanian, S., Abdoli, M. A., Khodadadi, A. & Karbassi, A. A cost-effective strategy for marine microalgae separation by electro-coagulation–flotation process aimed at bio-crude oil production: Optimization and evaluation study. Sep. Purif. Technol. 147, 156–165 (2015).

Cui, A., Liu, Z., Xiao, C. & Zhang, Y. Effect of micro-sized SiO2-particle on the performance of PVDF blend membranes via TIPS. J. Memb. Sci. 360, 259–264 (2010).

Vander Wiel, J. B. et al. Characterization of Chlorella vulgaris and Chlorella protothecoides using multi-pixel photon counters in a 3D focusing optofluidic system. RSC Adv. 7, 4402–4408 (2017).

Razmjou, A., Mansouri, J. & Chen, V. The effects of mechanical and chemical modification of TiO2 nanoparticles on the surface chemistry, structure and fouling performance of PES ultrafiltration membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 378, 73–84 (2011).

Sultan, H. et al. Green synthesis and investigation of surface effects of α-Fe2O3@ TiO2 nanocomposites by impedance spectroscopy. Materials. 15, 5768 (2022).

Satti, U. Q. et al. Simple two-step development of TiO2/Fe2O3 nanocomposite for oxygen evolution reaction (OER) and photo-bio active applications. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem Eng. Aspects. 671, 131662 (2023).

Suliman, Z. A., Mecha, A. C. & Mwasiagi, J. I. Effect of TiO2/Fe2O3 nanopowder synthesis method on visible light photocatalytic degradation of reactive blue dye, Heliyon. 10, e29648 (2024).

Guan, K. Relationship between photocatalytic activity, hydrophilicity and self-cleaning effect of TiO2/SiO2 films. Surf. Coat. Technol. 191, 155–160 (2005).

Magesan et al. Photodynamic and antibacterial studies of template-assisted Fe2O3-TiO2 nanocomposites. Photodiag Photodyn Therapy. 40, 103064 (2022).

Abd Elmohsen, S. A., Daigham, G. E., Mohmed, S. A. & Sidkey, N. M. Photocatalytic degradation of biological contaminant (E. Coli) in drinking water under direct natural sunlight irradiation using incorporation of green synthesized TiO2, Fe2O3 nanoparticles. Biomass Conv. Biorefin. 1–22 (2024).

Alghamdi, H. M. et al. Effect of the Fe2O3/TiO2 nanoparticles on the structural, mechanical, electrical properties and antibacterial activity of the biodegradable chitosan/polyvinyl alcohol blend for food packaging. J. Polym. Environ. 30, 3865–3874 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.B. performed the experimental work and wrote the original draft, S.Sh. is the corresponding author of the current study and did the conceptualization and methodology, supervised and validated the study, and reviewed the manuscript, M.S. and I.A. Supervised and validated the study, A.A. reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baniamerian, H., Shokrollahzadeh, S., Safavi, M. et al. Visible-light-activated Fe2O3–TiO2 nanoparticles enhance biofouling resistance of polyethersulfone ultrafiltration membranes against marine algae Chlorella vulgaris. Sci Rep 14, 24831 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76201-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76201-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Facile Synthesis of Fe2O3/Pt/TiO2 Nanowire Arrays Composite for Photo-Fenton-Like Degradation of Antibiotics Norfloxacin

Catalysis Letters (2025)

-

Advances and innovations in green nanotechnology for agro-environmental sustainability

Nanotechnology for Environmental Engineering (2025)

-

Efficient photocatalytic oxidative desulfurization of coal using Cu-TiO2/Fe3O4 heterojunction photocatalysts: synthesis optimization, kinetic analysis, and reusability studies

Journal of Nanoparticle Research (2025)