Abstract

Activated T follicular helper (aTfh) cells are likely important in host immune responses to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) mRNA vaccination. We characterized the immune responses of aTfh cells to the second (D2) and third (booster; D3) doses of an mRNA vaccine in the peripheral blood of 40 kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) and 17 healthy control volunteers (HCs). A significant increase in SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG antibody was seen after D3 in the KTRs; nonetheless, the levels after D2 and D3 were significantly lower than in the HCs. After D2, dramatic increases in activated CD45RA-CXCR5+ICOS+PD1+ circulating Tfh (acTfh) cells were observed in the HCs, as well as the seropositive patients among the KTRs, when compared with the seronegative patients among the KTRs. Unlike the HCs, KTRs had less prominent immune responses, including the acTfh and T cells that produce interferon gamma, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin 21. In addition, the increase in acTfh cells was significantly associated with anti-IgG antibody levels after D3. These results indicate impaired SARS-CoV-2-specific responses via acTfh cells in KTRs, and they suggest that acTfh cells in peripheral blood may play an important role in antibody maintenance following SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

When compared with the general population, immunocompromised kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) have an increased risk of developing severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection, and they also show impaired responses to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) mRNA vaccination due to maintenance immunosuppressive (IS) therapy1,2,3,4,5,6. T cell-mediated immune responses play a critical role in controlling viral infections. On viral infection, type I inflammation promotes virus-specific CD4+ T cell differentiation into T helper 1 (Th1) effector cells via interferon gamma (IFNγ) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), and into T follicular helper (Tfh) cells via interleukin 21 (IL21)7. Recently, circulating Tfh (cTfh) cells have been identified in patients after acute COVID-19 infection8,9,10. Regarding responses to vaccination, cytomegalovirus- and influenza-specific cells have been detected among the cTfh cells in peripheral blood after immunization11,12,13. Thus, Tfh cells might play an important role in the immune responses after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, and they might facilitate antigen-specific antibody production by B cells14. In our previous report, we demonstrated that, after normalization, the increase in CD38+ activated B cells was significantly associated with the SARS-CoV-2-specific antibody levels1.

Tfh cells are the conventional coordinators of protective antibody responses; they support immunoglobulin (Ig) class-switching and the development of humoral immunity inside the germinal center (GC) of secondary lymphoid tissues8,15,16. Activated Tfh (aTfh) cells have the CXCR5hiICOShiPD1hi phenotype. Förster et al. were the first to report follicular homing in C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 5 (CXCR5) and CXCR5-expressing CD4+ T cells in the tonsillar GC and peripheral blood17,18. Similarly, inducible T cell co-stimulator (ICOS), a member of the CD28 family of co-stimulatory molecules, is essential for the production and maintenance of Tfh cells in vivo19. In addition, programmed cell death 1 (PD1) is commonly used as a marker that is closely associated with the GC localization of T cells20.

In the context of transplantation, CXCR5+ICOS+PD1+ aTfh cells have been identified as a biomarker for predicting the formation of de novo donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies (DSA)21. Three months after kidney transplantation (KTx), cTfh cells were detected at higher frequencies in KTRs with DSA before KTx than in KTRs with no DSA before KTx22. Danger et al. reported that activated CD45RA- cTfh (acTfh) cells one year after KTx were independently associated with de novo DSA formation23.

To date, most SARS-CoV-2 studies in KTRs have been limited to the measurement of SARS-CoV-2-specific antibody titers. Changes in the cellular and humoral immune responses in KTRs might increase the risk of de novo DSA formation. In this study, we evaluated renal graft function, de novo DSA formation, and the acTfh cell responses elicited from the first dose (D1), second dose (D2), and third dose (booster; D3) of the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine in immunocompromised KTRs and in healthy control volunteers (HCs).

Results

Patient characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the KTRs and HCs are presented in Table 1. No significant differences in age, sex, or renal function were observed between the groups. Of the 70 KTRs, 66 (94.3%) were on three or more IS drugs, and 35 (50.0%) underwent additional induction therapy, including rituximab with double-filtration plasmapheresis. The mean duration between D1 and KTx was 4.8 ± 3.7 years (median [interquartile range]: 4.3 [2.2–6.4] years).

Increased SARS-CoV-2 S-RBD-specific IgG antibody response after D3 in KTRs

As we reported previously1, all HCs exhibited a S-RBD-IgG antibody response one month after D2; however, only 19 KTRs (27.1%) exhibited an antibody response against SARS-CoV-2 (P < 0.001; Fig. 1B). In the HCs, seropositivity for S-RBD-IgG antibody persisted for up to six months after D1; between D2 and D3, the levels of S-RBD-IgG antibody decreased significantly (P < 0.001), but they increased again to significantly higher levels one month after D3 (P = 0.002 and P < 0.001 compared with post-D2 and pre-D3, respectively; Fig. 1C,D). The median antibody levels were 8700 ± 2560 AU/mL at post-D2, 938 ± 165 AU/mL at pre-D3, and 18567 ± 4255 AU/mL at post-D3. In contrast, in KTRs, approximately three-fourths of the patients were seronegative one month after D2; however, one-half of KTRs subsequently became seropositive six months after D2. Overall, 34 KTRs (48.6%) were seropositive at pre-D3. The levels of S-RBD-IgG antibody in KTRs gradually increased up to six months after D1 and D2, before increasing markedly after D3 (P < 0.001; Fig. 1C,D); 51 KTRs (72.9%) acquired S-RBD-IgG antibodies after D3. The median antibody levels were 8.7 ± 8.6 AU/mL at post-D2, 39.5 ± 36.5 AU/mL at pre-D3, and 1463 ± 1438 AU/mL at post-D3. Nevertheless, the SARS-CoV-2 S-RBD-specific IgG antibody levels after D3 were significantly lower in the KTRs than in the HCs (P < 0.001).

Humoral immunity after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in KTRs. (A) Study design. (B) Changes in the serologic S-RBD IgG antibody responses against SARS-CoV-2 between 1 and 6 months after the second SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in KTRs (left) and HCs (right). (C, D) Serologic S-RBD IgG antibody responses against SARS-CoV-2 at different time points (C) and the timeline (D). Blue lines and bars represent the medians. Data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Second dose of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine mobilized CXCR5+ICOS+PD1+ aTfh cells in HCs

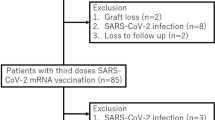

In the present study, the characteristics of the participants in the KTR and HC groups were matched (Table 2), and the immune responses in peripheral blood were evaluated following two vaccine doses in 40 KTRs and 17 HCs (10 KTx donors and 7 HCs) (Supplementary Fig. 1). First, we assessed the changes in circulating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells using CD45RA and CCR7 co-expression to identify the following four subsets (Supplementary Fig. 2): naïve T cells (CD45RA+CCD7+), central memory (CM) T cells (CD45RA-CCR7 +), effector memory (EM) T cells (CD45RA-CCD7-), and T effector memory re-expressing CD45RA (TEMRA) cells (CD45RA+CCR7-) (Supplementary Fig. 2A,C). We confirmed that similar trends were observed in all four subsets of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells before and after vaccination in the KTR and HC groups (Supplementary Fig. 2B,D).

Next, we attempted to determine whether Tfh cells contribute to the immune response induced by SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. The frequency of Tfh and circulating aTfh cells did not differ between KTRs and HCs before vaccination (median: 13.04 and 7.55 in KTRs vs. 13.01 and 6.55 in HCs, Fig. 2A,C). There was no absolute increase in the frequency of CD45RA-CXCR5+ cTfh cells among the non-Treg cells in either the KTR group or the HC group, and no increase was seen after normalization between the baseline and post-vaccination levels (median: 13.04 to 12.77 in KTRs vs. 13.01 to 13.55 in HCs, Fig. 2A,B). In contrast, vaccinated HCs had a significantly higher frequency of circulating aTfh cells co-expressing ICOS and PD1 (median: 7.55 to 6.90 in KTRs vs. 6.55 to 8.55 in HCs, Fig. 2C,D). Remarkably, the changes in CD45RA-CXCR5+ICOS+PD1+ circulating aTfh cells after normalization to baseline were markedly higher in the HCs, as well as in the seropositive KTRs, when compared with the seronegative KTRs (median: 0.25 in seropositive KTRs vs. − 0.11 in seronegative KTRs vs. 0.40 in HCs, P < 0.001 and P = 0.04, respectively; Fig. 2D). In addition, simple linear regression analysis after normalization showed that the increase in acTfh cells was significantly associated with the S-RBD-IgG antibody levels after D2 (R2 = 0.51, P < 0.0001, Fig. 2E). Taken together, these results suggest that circulating aTfh cells may be suitable as a biomarker for estimating SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-mediated immune responses.

Quantification of cTfh cells in PBMCs before and 7 days after D2. (A–D) Representative gating strategies and scatterplots of CD45RA-CXCR5+ cTfh (A) and CD45RA-CXCR5+ICOS+PD1+ acTfh (C) cells among the non-Treg cell subsets in the two groups before and post-D2. Comparison of the frequency and normalized increases in the cTfh (B) and acTfh (D) cells in the two groups (SP seropositive, SN seronegative). (E) Scatterplot of anti-S-RBD IgG levels and normalized increases in acTfh cells determined by flow cytometric analysis. Data were obtained from 57 samples (40 from KTRs and 17 from HCs). A moderate but significant correlation of anti-S-RBD IgG levels with normalized increases in the acTfh cells is seen after D2. Blue lines and bars represent the medians. Data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test (*P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001).

mRNA vaccine-induced aTfh cell responses are suppressed in KTRs

To determine whether changes in aTfh cells are linked to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, we collected PBMCs over time after each vaccination and cultured them with the SARS-CoV-2 overlapping peptide against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. From the flow cytometric analysis, the frequency of CXCR5-expressing total Tfh cells after stimulation did not differ between the KTR and HC groups throughout the series of vaccinations (median: − 0.09 and − 0.03 in KTRs vs. 0.03 and 0.15 in HCs, Fig. 3A). In particular, our results demonstrated that the changes in CD45RA-CXCR5+PD1+ acTfh cell subsets among the PBMCs persisted until D3 in the HCs, but not in the KTRs (median: − 0.09 and 0.09 in KTRs vs. 0.20 and 0.29 in HCs, P = 0.04 after D2 and P = 0.008 after D3, respectively; Fig. 3B,C). Simple linear regression analysis after normalization showed that the increase in acTfh cells after stimulation was significantly associated with the S-RBD-IgG antibody levels after both D2 and D3 (Fig. 3D). The magnitude of the acTfh cell increase after D3 demonstrated a strong linear relationship with the magnitude of the S-RBD-IgG antibody production within the analyzed range (R2 = 0.25 and P < 0.001, and R2 = 0.43 and P < 0.001 for D2 and D3, respectively). Interestingly, one patient, who was diagnosed with class II de novo DSA after vaccination became seropositive at 1882 AU/mL after D3, but did not show any increase in mRNA vaccine-induced acTfh cells.

mRNA vaccine-induced Tfh cell responses 7 days after D2 and D3. (A) Comparison of the frequency in total cTfh cells after stimulation. (B, C) Representative gating strategies and scatterplots depicting the frequency of CD45RA-CXCR5+PD1+ acTfh cells after stimulation in circulating CD4+ T cells in the two groups at before, post-D2, and post-D3 measured by flow cytometry (B). Comparison of the frequency and normalized increases in acTfh cells (C). (D) Scatterplot of the anti-S-RBD IgG levels and normalized increases within acTfh cells by flow cytometric analysis. Data were obtained from 57 samples (40 from KTRs and 17 from HCs). A moderate but significant correlation of anti-S-RBD IgG levels with normalized increases in the acTfh cells is seen after D3. Blue lines and bars represent the medians. Data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

T cell-mediated IFNγ, TNFα, and IL21 production is boosted following vaccination in HCs, but not in KTRs

To confirm the acTfh cell responses after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, we measured T cell-mediated responses by flow cytometry after stimulating a series of PBMCs with SARS-CoV-2 overlapping peptide against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, followed by staining for intracellular IFNγ, TNFα, and IL21 (Supplementary Fig. 3). To confirm the acTfh cell responses after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, we measured T cell-mediated responses by flow cytometry after stimulating a series of PBMCs with SARS-CoV-2 overlapping peptide against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, followed by staining for intracellular IFNγ, TNFα, and IL21 (Supplementary Fig. 3). Figure 4A,D,G) shows representative tSNE plots of the total CD4+ T cells expressing novel cytokines, including IFNγ, TNFα, and IL21, in the HCs. By analyzing the PBMCs after stimulation, we found that CD4+ T cells actively produced IL21, and that the cells that produced IFNγ and TNFα were different cells (Fig. 4A,D vs. Figure 4G). In the HCs, the IFNγ+ and TNFα+ CD4+ T cells increased significantly over time between D2 and D3 (median: 0.12, 0.14, and 0.17 for IFNγ and 0.06, 0.09, and 0.12 for TNFα in KTRs vs. 0.08, 0.25, and 0.21 for IFNγ and 0.06, 0.14, and 0.12 for TNFα in HCs, all P < 0.001; Fig. 4B,C,E,F). In addition, PBMCs from the HCs showed dramatically higher production of IL21 in response to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (median: 0.19, 0.14, and 0.16 vs. 0.09, 0.29, and 0.33 in HCs, P = 0.03 and P = 0.02 for D2 and D3, respectively; Fig. 4H,I). Supplementary Fig. 4A,D shows representative tSNE plots of the total CD8+ T cells expressing IFNγ and TNFα in the HCs. The IFNγ and TNFα spots in the CD8+ T cells were similar in magnitude to those in the CD4+ T cells (Supplementary Fig. 4A,D). Although IFNγ- and TNFα-producing CD8+ T cells showed weaker responses than CD4+ T cells, the trends observed in the CD8+ T cells were consistent with those of the CD4+ T cells (median: 0.09, 0.09, and 0.11 for IFNγ and 0.02, 0.02, and 0.02 for TNFα in KTRs vs. 0.07, 0.21, and 0.23 for IFNγ, and 0.01, 0.04, and 0.05 for TNFα in HCs, all P < 0.001; Supplementary Fig. 4B,C,E,F). Throughout the series of vaccinations, KTRs exhibited less prominent acTfh cell immune responses than the HCs after normalization to baseline. Interestingly, KTRs exhibited a significantly higher frequency of TNFα+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood after D3 (Fig. 4F, Supplementary Fig. 4F). Similar results, in terms of IFNγ and TNFα production, were observed from the CBA assays using the supernatants from the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein-stimulated PBMCs (median: 3.11, 5.89, and 11.45 for IFNγ and 12.32, 13.13, and 36.31 for TNFα in KTRs vs. 1.51, 26.76, and 14.09 for IFNγ and 7.24, 25.75, and 26.17 for TNFα in HCs, Fig. 5A,B). Though no increase in IL21 production was seen in the PBMCs collected from the KTRs after each vaccination, a significant increase was observed in the PBMCs collected from the HCs (median: 21.50, 22.59, and 19.90 vs. 0.00, 36.22, and 19.99 in HCs, P < 0.001) (Fig. 5C).

CD4+ T cell-mediated immune responses after stimulation in vitro. (A–I) Representative tSNE plots of flow cytometry for the HCs at before, post-D2 (7 days after D2), and post-D3 (7 days after D3). Using tSNE projection of CD4+ T cells for five HCs participants pooled, gates defining the indicated cell subsets and relative protein expression levels of IFNγ (A), TNFα (D), and IL21 (G) are shown. Black highlighted areas are with IFNγ+, TNFα+, and IL21+ cells. Representative gating strategies and scatterplots of IFNγ+ (B), TNFα+ (E), and IL21+ (H) cells within CD4+ T cells in KTRs (red) and HCs (black) at before, post-D2, and post-D3, measured by flow cytometry. Comparison of the frequency of IFNγ+ (C), TNFα+ (F), and IL21+ (I) cells in the two groups. Blue bars represent the medians. Data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). NC, negative controls.

Detection of the production of three distinct T cell-mediated inflammatory cytokines in the supernatants after stimulation. (A–C) Comparison of the production of IFNγ (A), TNFα (B), and IL21 (C) in KTRs (red) and HCs (black) at before, post-D2, and post-D3, measured by CBA assays. Blue bars represent the medians. Data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). NC negative controls, PC positive controls.

Reactogenicity and clinical outcomes after D3 in KTRs

Local pain and muscle pain were the most commonly reported adverse effects from D1 to D3 (Supplementary Fig. 5A,B). With the exception of these two symptoms, KTRs reported a markedly higher incidence of local and systemic events after D3. During the one-year follow-up, no significant changes were found in the serum creatinine levels and the estimated glomerular filtration rate in the KTRs (Supplementary Fig. 5C). Except for one patient, who was diagnosed with class II de novo DSA seven months after D1, all KTRs maintained excellent renal function for one year without acute rejection or de novo DSA formation (Supplementary Fig. 5D). The patient, who was diagnosed with class II de novo DSA after vaccination, became seropositive at 1882 AU/mL after D3, but did not show any increase mRNA vaccine-induced acTfh cells. No treatments for de novo DSA formation were performed throughout this study.

Discussion

An important finding of this study was that the levels of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG antibody in KTRs increased gradually from D2 to D3. Notably, D3 was effective as it induced anti-IgG antibodies without causing any serious adverse events, such as anaphylaxis, and renal function was well maintained after one year without de novo DSA formation in KTRs. The results suggest that the cellular and humoral immune responses to D3 were markedly higher than those to D1 or D2 in KTRs; however, the responses in KTRs were still significantly lower than in HCs.

The unique features of Tfh cell-based immune responses are necessary for the efficient differentiation of plasma cells and memory B cells inside the GCs of secondary lymphoid tissues. In addition, Tfh cells promote B cell differentiation by producing IL218. Regarding the Tfh cells in GCs, Lederer et al. recently reported that the presence of Tfh cells in draining lymph nodes was significantly associated with SARS-CoV-2 S-RBD-specific IgG antibody formation14. CD45RA- cTfh cells were found to have a similar phenotype and function as their bona fide counterparts in the GCs of secondary lymphoid tissues11. Transplant researchers have been focusing on cTfh cells in peripheral blood because it is difficult to analyze Tfh cells in secondary lymphoid tissues in human KTRs. The cTfh cells are considered to be useful as a biomarker for humoral alloreactivity, and antigen-specific cTfh cells exhibit an activated ICOS+PD1+ phenotype as acTfh cells21. In fact, circulating aTfh cells expressing high levels of ICOS and PD1 have been reported in peripheral blood after vaccination13,24,25. Consistent with these reports, we found that the changes in acTfh cells, but not the frequency of these cells, after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination were significantly associated with the production of anti-S-RBD IgG antibody.

Based on findings in transplant recipients26,27,28, which showed that humoral immune responses were gradually increased by having a seropositive response up to 1–5 months after D2, the interval after D2 is considered to be best suited for assessing the SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG response in KTRs. In addition, the trends in SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG antibody formation in KTRs after the D3 boost were consistent with the results of previous reports29,30.

The measurement of inflammatory cytokines for evaluating T cell-mediated responses provides important insights into how KTRs respond to SARS-Cov-2 mRNA vaccination. The novel findings of our study are that CD4+ T cells actively produced IL21; cells producing IFNγ and TNFα were different cells; and IL21, IFNγ, and TNFα production was strongly associated with SARS-Cov-2 mRNA vaccination. The result that SARS-Cov-2-S-RBD-specific responses are IL21-dependent is consistent with recent reports10,31. Taken together, our results suggest that, when compared with HCs, acTfh cell responses are impaired in KTRs, even after D3.

A strength of this study is that we analyzed stimulated PBMCs in vitro to assess the cellular and humoral immune responses after a series of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccinations, and we compared the results between KTRs and HCs, which included KTx donors. However, this study has several limitations. First, this study was conducted using data from a single center. Second, we did not perform any kidney graft biopsies after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Third, we did not monitor KTRs for worsened renal function and de novo DSA testing for a long time after vaccination. A large-scale prospective study with a longer follow-up could be expected to yield useful results for precisely evaluating the risk of de novo DSA formation. However, we observed stable renal function and no serious rejection throughout this study.

In summary, this is the first study to show significantly impaired mRNA vaccine-induced acTfh cell responses in KTRs. The results demonstrate that acTfh cells in peripheral blood are strongly associated with S-RBD IgG antibody maintenance following SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in HCs and immunocompromised KTRs.

Materials and methods

Populations and study design

The present prospective cohort study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tokai University Hospital at Isehara, Japan (#21-R007). The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was conducted from January 2021 to June 2022. All patients provided written and oral informed consent for participation in this study. The participants received two intramuscular injections of the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine (BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273) 21 days apart, followed by a third booster vaccination (D3) six months after the second injection. All participants self-evaluated specific local and systemic adverse events, and reported the use of any medications at 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 14, and 21 days after each vaccination. The renal function of all KTRs was assessed as described previously32. Details are provided in the supporting information. The HCs, which included KTx donors, were recruited through our outpatient care unit. In this prospective cohort study, a total of 90 participants used a safety sheet to score and record adverse events after each SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. Serum samples were collected from these 90 participants, which consisted of 70 KTRs who had been followed-up for at least six months after KTx, and 20 HCs (10 KTx donors and 10 healthy volunteers). Participant characteristics were then matched between the groups for the following factors: age, sex, renal function, and vaccine type. All KTRs received stable IS therapy without changes, and no participants tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection over the course of this study.

Isolation of serum and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)

Whole blood was collected for the isolation of serum and PBMCs. Referring to previous reports on transplant recipients26,27,28, serum samples were obtained before D1, one month after D2, and within seven days before and one month after D3. As described previously1, matched PBMC samples were also obtained before D1, and one week after D2 and D3 (Fig. 1A). PBMCs were isolated from 8 mL of venous blood by density gradient centrifugation using cell preparation tubes (BD Vacutainer® CPTTM #362761; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). The isolated PBMCs and serum samples were stored in liquid nitrogen and in a freezer at −80 ℃, respectively.

Measurement of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG antibodies

The detection of IgG antibodies was performed as described previously1. Details of the assay are described in the supporting information.

Monitoring of Tfh cell responses by flow cytometry

Flow cytometric assays were performed as described previously32. Details of the assay are described in the supporting information.

Monitoring of cell-mediated T cell responses by flow cytometry

After thawing and counting, the cells were resuspended in TexMACS™ medium (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany) at a final density of 10 × 106 cells/mL, and 1 × 106 cells in 100 µL were then plated in duplicate wells of 96-well plates. After resting overnight, the PBMCs were stimulated with SARS-CoV-2 overlapping peptide against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (PepTivator® SARS-CoV-2 Prot_S Complete—research grade; Miltenyi Biotec) at a final concentration of 1 μg/mL with 1 μg/mL anti-human monoclonal CD28/CD49d (BD Biosciences) for 5 h; GolgiStop (BD Biosciences) was added for the last 3.5 h of stimulation. Negative controls containing CD28/CD49d alone and positive controls containing Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (10 ng/mL) and ionomycin (0.2 µg/mL) were also run for each sample. Details of the intracellular staining assay are described in the supporting information.

Monitoring of inflammatory cytokine production by cytometric bead array (CBA) assays

After SARS-CoV-2 spike-specific stimulation for 5 h without GolgiStop (BD Biosciences), the supernatants from the cell cultures were collected and stored in a freezer at − 80 ℃. Various capture beads (IFNγ, TNFα, and IL21 CBA human Soluble Protein Flex Kit; BD Biosciences) at 50 μL each were then added to 25 μL of test samples and 25 μL of assay diluents in 1.5 mL tubes for 1 h at room temperature. Then, 50 μL of phycoerythrin (PE) detection reagents were added, and the samples were incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The coated samples were then washed and analyzed using a fluorescence-activated cell sorting Fortessa analyzer (BD Biosciences). Standard solution and negative and positive controls were also run for each experiment.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, Inc., [San Diego], CA, USA). Significant differences were evaluated using the chi-squared test for discrete variables. For comparisons between two groups, either a two-tailed, unpaired t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test was used. The relationship between two variables was examined by simple linear regression analysis. All KTRs were monitored for renal function and screened for DSA values for one year following D1. The prevalence of de novo DSA formation in the KTRs was calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method. In all tests, P < 0.05 was considered to indicate significance for each comparative analysis.

Data availability

Data to support the findings in the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- KTRs:

-

Kidney transplant recipients

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome–coronavirus 2

- IS:

-

Immunosuppressive

- Th1:

-

T helper 1

- IFNγ:

-

Interferon gamma

- TNFα:

-

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- Tfh:

-

T follicular helper

- IL21:

-

Interleukin 21

- cTfh:

-

Circulating TfhT

- GC:

-

Germinal center

- aTfh:

-

Activated Tfh

- CXCR5:

-

C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 5

- ICOS:

-

Inducible T cell co-stimulator

- PD1:

-

Programmed cell death 1

- DSA:

-

Donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies

- KTx:

-

Kidney transplantation

- acTfh:

-

Activated circulating Tfh

- HCs:

-

Healthy control volunteers

- PBMCs:

-

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- D1:

-

Dose 1

- D2:

-

Dose 2

- D3:

-

Dose 3

- S-RBD:

-

Spike 1 protein receptor binding domain

- FITC:

-

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

- PE:

-

Phycoerythrin

- sCr:

-

Serum creatinine

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- CM:

-

Central memory

- EM:

-

Effector memory

- TEMRA:

-

Effector memory re-expresses CD45RA

- CyA:

-

Cyclosporine

- Tac:

-

Tacrolimus

- MMF:

-

Mycophenolate mofetil

- MZ:

-

Mizoribine

- EVR:

-

Everolimus

References

Takiguchi, S. et al. Immunological imprint on peripheral blood in kidney transplant recipients after two doses of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in Japan. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 9, 999374. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.999374 (2022).

Tomita, Y., Uehara, S., Terada, M., Yamamoto, N. & Nakamura, M. Effects of anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in living kidney transplant recipients prior to transplantation. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-024-02535-1 (2024).

Danthu, C. et al. Humoral response after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in a cohort of hemodialysis patients and kidney transplant recipients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 32, 2153–2158. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2021040490 (2021).

Yelin, D. et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibody dynamics among kidney transplant recipients 3 months after BNT162b2 vaccination: a prospective cohort study. Clin. Kidney J. 15, 992–998. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfac031 (2022).

Rincon-Arevalo, H. et al. Impaired humoral immunity to SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients and dialysis patients. Sci. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.abj1031 (2021).

Piotrowska, M. et al. Local and systemic immunity are impaired in end-stage-renal-disease patients treated with hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis and kidney transplant recipients immunized with BNT162b2 Pfizer-BioNTech SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Front. Immunol. 13, 832924. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.832924 (2022).

Hale, J. S. et al. Distinct memory CD4+ T cells with commitment to T follicular helper- and T helper 1-cell lineages are generated after acute viral infection. Immunity 38, 805–817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.020 (2013).

Crotty, S. T follicular helper cell differentiation, function, and roles in disease. Immunity 41, 529–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.004 (2014).

Rodda, L. B. et al. Functional SARS-CoV-2-specific immune memory persists after mild COVID-19. Cell 184, 169-183.e117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.029 (2021).

van der Ploeg, K. et al. TNF-α. Cell Rep. Med. 3, 100640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100640 (2022).

Morita, R. et al. Human blood CXCR5(+)CD4(+) T cells are counterparts of T follicular cells and contain specific subsets that differentially support antibody secretion. Immunity 34, 108–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.012 (2011).

He, J. et al. Circulating precursor CCR7(lo)PD-1(hi) CXCR5⁺ CD4⁺ T cells indicate Tfh cell activity and promote antibody responses upon antigen reexposure. Immunity 39, 770–781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2013.09.007 (2013).

Herati, R. S. et al. Successive annual influenza vaccination induces a recurrent oligoclonotypic memory response in circulating T follicular helper cells. Sci. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.aag2152 (2017).

Lederer, K. et al. Germinal center responses to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines in healthy and immunocompromised individuals. Cell 185, 1008-1024.e1015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2022.01.027 (2022).

Qi, H. T follicular helper cells in space-time. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16, 612–625. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri.2016.94 (2016).

Ma, C. S. & Phan, T. G. Here, there and everywhere: T follicular helper cells on the move. Immunology 152, 382–387. https://doi.org/10.1111/imm.12793 (2017).

Förster, R., Emrich, T., Kremmer, E. & Lipp, M. Expression of the G-protein–coupled receptor BLR1 defines mature, recirculating B cells and a subset of T-helper memory cells. Blood 84, 830–840 (1994).

Förster, R. et al. A putative chemokine receptor, BLR1, directs B cell migration to defined lymphoid organs and specific anatomic compartments of the spleen. Cell 87, 1037–1047. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81798-5 (1996).

Akiba, H. et al. The role of ICOS in the CXCR5+ follicular B helper T cell maintenance in vivo. J. Immunol. 175, 2340–2348. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2340 (2005).

Haynes, N. M. et al. Role of CXCR5 and CCR7 in follicular Th cell positioning and appearance of a programmed cell death gene-1high germinal center-associated subpopulation. J. Immunol. 179, 5099–5108. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5099 (2007).

La Muraglia, G. M., Wagener, M. E., Ford, M. L. & Badell, I. R. Circulating T follicular helper cells are a biomarker of humoral alloreactivity and predict donor-specific antibody formation after transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.15517 (2019).

de Graav, G. N. et al. Follicular T helper cells and humoral reactivity in kidney transplant patients. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 180, 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/cei.12576 (2015).

Danger, R. et al. CXCR5. Front. Immunol. 10, 2071. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.02071 (2019).

Heit, A. et al. Vaccination establishes clonal relatives of germinal center T cells in the blood of humans. J. Exp. Med. 214, 2139–2152. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20161794 (2017).

Herati, R. S. et al. Circulating CXCR5+PD-1+ response predicts influenza vaccine antibody responses in young adults but not elderly adults. J. Immunol. 193, 3528–3537. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1302503 (2014).

Giannella, M. et al. Evaluation of the kinetics of antibody response to COVID-19 vaccine in solid organ transplant recipients: The prospective multicenter ORCHESTRA cohort. Microorganisms https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10051021 (2022).

Alejo, J. L. et al. Six-month antibody kinetics and durability in SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccinated solid organ transplant recipients. Transplantation 106, e109–e110. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000003975 (2022).

Boyarsky, B. J. et al. Antibody kinetics and durability in SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccinated solid organ transplant recipients. Transplantation 105, e137–e138. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000003863 (2021).

Charmetant, X. et al. Infection or a third dose of mRNA vaccine elicits neutralizing antibody responses against SARS-CoV-2 in kidney transplant recipients. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, eabl6141. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abl6141 (2022).

Cirillo, L. et al. Response to third dose of vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 in adolescent and young adult kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation 106, e386–e387. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000004199 (2022).

Malahe, S. R. K. et al. The role of interleukin-21 in COVID-19 vaccine-induced B cell-mediated immune responses in patients with kidney disease and kidney transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajt.2023.05.025 (2023).

Tomita, Y. et al. CD45RA-CD25highCD127-CD4+ activated regulatory T cells are correlated with de novo donor-specific anti-HLA antibody formation after kidney transplantation in standard immunosuppression. Int. Immunopharmacol. 97, 107661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107661 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the personnel of the Tokai University Support Center for Medical Research and Education for technical support with the flow cytometric assays. We also thank the Tokai University General Research Organization for funding the editing and proofreading of this paper.

Funding

This work was supported by 2020 and 2023 KAKENHI grants (Nos. 20K17564 and 23K15460 to Y.T.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Participated in research conception or design of the work: Yusuke Tomita (YT) and Michio Nakamura (MN). Participated in interpretation of data analysis: YT and Norio Yamamoto (NY). Contributed new software used in the work: YT and NY. Participated in the writing of the paper: YT. Participated in the revising of the paper: NY and MN. Participated in the performance of the research: YT, Saeko Uehara (SU), Mari Terada (MT), and NY.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tomita, Y., Uehara, S., Terada, M. et al. Impaired SARS-CoV-2-specific responses via activated T follicular helper cells in immunocompromised kidney transplant recipients. Sci Rep 14, 24571 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76251-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76251-x