Abstract

The association between self-rated health (SRH) and the development of atrial fibrillation (AF) in the general population remains underexplored. We reviewed the data of 9,895 participants in the Ansung–Ansan cohort study, a community-based Korean study. SRH was categorised as ‘poor’, ‘fair’, or ‘good’. A newly developed AF was identified through biennial electrocardiography examinations and/or a self-reported history of physician-determined diagnoses. Over a median follow-up of 11 years, 149 patients (1.5%) developed AF. Compared with the ‘good’ group, the ‘poor’ group exhibited a higher risk of incident AF (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.85; 95% confidence interval, 1.19–2.87). Old age, female sex, lower educational level, smoking, cardiovascular diseases (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and coronary artery disease), and inflammation were associated with ‘poor’ SRH. Along with SRH, age, male sex, urban residence, hypertension, and myocardial infarction were also associated with a higher risk of incidental AF. The combined model, which included conventional risk factors and SRH, demonstrated a marginally improved performance in predicting incident AF (concordance index: 0.704 vs. 0.714, P = 0.058). Poor SRH is independently associated with the development of AF in Korean adults. However, it plays a limited role in AF surveillance when combined with conventional AF risk factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common type of cardiac arrhythmia associated with significant morbidity and mortality1. It poses a considerable burden on healthcare systems worldwide owing to its high incidence; potential complications, such as stroke and heart failure; and associated healthcare costs2. Identifying its risk factors is crucial for the development of effective prevention and management strategies.

Self-rated health (SRH) encompasses the subjective assessment of an individual of their overall health and well-being. Several studies have demonstrated the significance of SRH as a predictor of cardiovascular diseases and mortality3,4. Poor SRH is associated with the development of chronic kidney disease5, a major risk factor for AF6. However, studies on the role of SRH in predicting the incidence of AF in the general population are limited.

Investigating the potential association between SRH and the development of AF could help in developing a straightforward and cost-effective method for stratifying the risk of AF in the general population, potentially facilitating more individualised screening for AF. This prospective longitudinal community-based cohort study aimed to bridge this knowledge gap by investigating the association between SRH and incident AF in the general population.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The study population had a mean age of 52.2 ± 8.9 years, with 4,687 (47.4%) participants being men. Hypertension (HTN) and diabetes mellitus (DM) were present in 1,526 (15.4%) and 659 (6.7%) patients, respectively. The average body mass index (BMI) was 24.6 ± 3.1 kg/m2.

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the SRH group. Among the 9,895 participants surveyed, 3,380 (34.2%) rated their health status as ‘very poor’ or ‘poor’. Most baseline characteristics significantly differed among the SRH groups, except for physical activity and the presence of heart failure. Compared with the ‘fair’ and ‘good’ SRH groups, the participants in the ‘poor’ SRH group were more likely to be older, women, and rural residents and have lower education levels. The ‘poor’ SRH group had a lower proportion of current smokers and current drinkers. Compared with the ‘fair’ and ‘good’ SRH groups, those in the ‘poor’ SRH group was more likely to experience central obesity (waist circumference [WC] ≥ 90 cm for men and ≥ 85 cm for women), HTN, DM, myocardial infarction (MI), non-MI coronary artery disease (CAD), asthma, chronic lung disease, and stroke. Laboratory data indicated that haemoglobin A1c, white blood cell count, and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were higher in the ‘poor’ SRH group than in the ‘fair’ and ‘good’ SRH groups.

Risk of AF according to the SRH status

During a median follow-up period of 11.0 ± 4.3 years (interquartile range, 6–12 years), new-onset AF was observed in 149 (1.5%) participants. Of these, 129 participants were identified as having new-onset AF through a 12-lead electrocardiography (ECG). The total observation period amounted to 86,587.1 person-years resulting in an AF incidence rate of 172.1 cases per 100,000 person-years. The Kaplan–Meier curves for the cumulative incidence of AF according to the SRH status are shown in Fig. 1. The incidence of AF was significantly higher in the ‘poor’ SRH group than in the ‘good’ SRH group (1.9% vs. 1.2%; log-rank P = 0.01). In the Cox proportional hazard model, as shown in Table 2, the ‘poor’ SRH group had a higher risk of incident AF than that in the ‘good’ SRH group after adjusting for all relevant covariates (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.79; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.16–2.76).

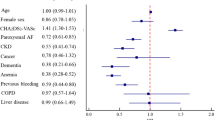

Factors associated with poor SRH

Older age, HTN, DM, cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease, asthma, chronic lung disease, and higher CRP levels were associated with poor SRH (Table 3). However, male sex, urban residence, high education level, current smoking, and drinking were negatively associated with poor SRH. In the multivariate model, various factors such as older age, sex, education level, current drinking, HTN, DM, CAD, asthma, stroke, and high CRP level remained significantly associated with poor SRH. Current smoking showed a positive association with poor SRH in the multivariate model, which was the opposite to the result in the univariate model.

SRH and AF risk discrimination

SRH alone only yielded a modest Harrell’s concordance index (C-index) for predicting incident AF (Model 0; C-index, 0.607 [95% CI, 0.540–0.675]; P < 0.001) (Fig. 2; Table 4). The C-index for predicting incident AF using conventional risk factors was significantly higher than that achieved using SRH alone (Model 1; C-index, 0.708; 95% CI, 0.667–0.749). The predictive performance of the model comprising both SRH and conventional risk factors (Model 2) showed a slight improvement compared with that of the model comprising only conventional risk factors (Model 1), with only a marginal increase in the C-index (Model 2 vs. Model 1:0.714 [95% CI, 0.675–0.755] vs. 0.704 [95% CI, 0.664–0.745], P = 0.058).

Original SRH response and new-onset AF

Although the log-rank test was not significant, the Kaplan–Meier survival curve showed a significant trend toward increased incidence of AF as the original SRH responses worsened (Supplementary Fig S2). The multivariate Cox proportional hazards (CPH) model showed that poor SRH was significantly associated with a higher risk of new-onset AF after adjusting for covariates. Additionally, a marginally significant variation of incident AF was found among the original SRH responses in the analysis of variance (P = 0.0585, Supplementary Table S1).

Discussion

In this large population-based cohort study, the incidence of newly developed AF was significantly higher in patients with poor SRH than in those with good SRH. The findings indicate that the likelihood of developing AF varied based on the responses to the SRH questionnaire. New-onset AF only occurred in 62.3% of the participants who rated their health as ‘good’ compared with those who rated it as ‘poor’. This result suggests a significant link between subjective health perceptions and the pathophysiology of AF development in the general population. Poor SRH was significantly associated with conventional risk factors including old age, low education level, HTN, DM, cardiovascular diseases, and high inflammatory marker levels. Although ‘poor’ SRH was significantly associated with incident AF, its inclusion did not improve the predictive power of the model that incorporated conventional AF risk factors.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the association between SRH and the development of AF in a general population. In a cohort of older patients with AF, Abu et al. reported that one in every six older patients with AF rated their health status in the two lowest categories out of five, and a poorer health status was more prevalent in patients with multimorbidity7. However, their study did not investigate whether SRH was a risk factor for AF. Instead, they speculated that AF might serve as an indicator of frailty, which could manifest as poor SRH.

Because it is obvious that the personal perception of well-being cannot facilitate future AF development, the observed association between poor SRH at baseline and incident AF during follow-up might appear to be reversed in the temporal dimension. Nevertheless, several factors may explain this baffling association. First, poor SRH and AF share common risk factors. Advanced age, HTN, and cardiovascular diseases such as MI are all established risk factors for AF. These risk factors were also associated with poor SRH, as observed in our results and previous studies8,9,10. Additionally, increased systemic inflammation, as indicated by elevated CRP levels, has also been associated with poor SRH and incident AF10,11. Consequently, a negative perception of one’s health status resulting from these underlying comorbidities and conditions may precede the onset of AF by several years.

Second, new-onset AF was identified using a standard 12-lead ECG and self-reported physician-based diagnosis. These AF identification methods are susceptible to delays between the onset of symptoms and the formal diagnosis of AF. All cases of AF identified in this study, except for two, were persistent chronic AF. Typical AF begins with an episode of tachycardia by paroxysmal AF. This episode may be followed by recurrent episodes of paroxysmal AF, eventually progressing to chronic AF with stable symptoms over a longer follow-up period. Therefore, delays between the true onset of AF and the identification of AF are likely. Although ambulatory ECG monitoring may facilitate the detection of subclinical or paroxysmal AF12, the scheduled biennial ECG assessment method used in our study may have caused a time delay between symptom onset and AF diagnosis. This time lag may account for the apparent predictive value of SRH for new-onset AF.

Third, unmeasured confounders, especially those related to social, psychological, or behavioural predispositions affecting both SRH status and AF incidence, may influence the observed association between SRH and new-onset AF. Obstructive sleep apnoea, a significant behavioural risk factor for AF, is also known to affect self-reported general health status, assessed using the short form (SF)-36 questionnaires13. Previous studies have indicated that lower educational levels are associated with poor SRH, which is consistent with our results7. Poor SRH is also associated with various variables related to socioeconomic status. This association creates different levels of discrepancy between SRH and physical health depending on socioeconomic status, which is considered a limitation of SRH14. However, the tendency for poor SRHs in participants with low socioeconomic status may explain the link between poor SRH and incident AF, as the association between socioeconomic status and incident AF has been established15.

SRH is useful for comparing the health status across population groups as an outcome variable in clinical trials and as a risk assessment tool in routine clinical practice16. SRH can predict mortality and hospitalisation. It also has a predictive value for stroke when added to a model that includes traditional risk factors, including smoking, high BMI, high cholesterol levels, HTN, and DM17, and the Framingham risk stratification model for coronary heart disease and cardiovascular death18. Although we found that the improvement in the predictive power of the model for incident AF was only marginally significant, further investigations in diverse populations could determine whether the model has additional predictive value for current risk assessment tools.

The strength of the current study lies in its inclusion of a large sample size of a well-managed prospective cohort of the general population, which provides robust confidence in the association between poor SRH and the incidence of AF. The SRH employed in this study was a simple yet powerful, valid, and reproducible measure for quantifying health perception. However, this study has several limitations. First, owing to the observational nature of the current study, establishing a causal relationship was challenging. Although we adjusted for relevant covariates such as age, sex, socioeconomic status, and comorbidities, the unmeasured confounding factors may have contributed to the association between SRH and incident AF. Second, the incidence of AF was relatively low compared with that in other cohort studies19,20, which may indicate an under-recognition of AF. The use of biennial 12-lead standard ECG and self-reported physician diagnosis could have resulted in under-recognition of paroxysmal AF. However, Northeast Asians have the lowest prevalence of AF worldwide21, and a previous study by Lee et al. reported a similarly low incidence of AF in a nationwide insurance claims database of the Korean population22. Therefore, the under-recognition of paroxysmal AF may not have significantly affected the results of this study. Third, SRH was measured once at baseline, although it would most likely have varied throughout the follow-up period. Using time-varying CPH models with SRH as a time-varying covariate may have yielded different insights into the association between SRH and the risk of AF. However, unlike variables with established causal links such as blood pressure, a poor perception of health does not have a direct causal effect on AF development. Therefore, this study focused on examining the predictive value of SRH for new-onset AF. Finally, as death prevents the observation of new-onset AF, competing risk models may have provided an unbiased and accurate estimate of the cumulative incidence of AF. However, given that the participants were relatively healthy middle-aged community residents with a low risk of death, and the primary hypothesis of the study was to examine the independent association between SRH and incident AF, competing risk models may yield results similar to those obtained in this study.

In conclusion, the incidence of AF increases in patients who perceive their health as poor compared with those who perceive it as healthy. Poor perception of health is independently associated with incident AF and shares common risk factors with AF, including advanced age, lower education level, current smoking status, HTN, DM, CAD, asthma, stroke, and inflammation. Although SRH alone does not improve the predictive power of the conventional risk factor model for the incident AF, it may serve as a simple indicator of the risk of AF in the general population.

Methods

Study population

This study included 9,895 participants, aged 40–69 years, from the Ansung–Ansan cohort of the Korean Genome Epidemiology Study, conducted by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. This study investigated the genetic and environmental factors contributing to the prevalence of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. Individuals residing in rural (Ansung) and urban (Ansan) communities were enrolled between June 2001 and January 2003. The detailed protocols have been described in previous publications23,24.

A total of 10,030 eligible individuals who had resided in Ansung (n = 5,018) or Ansan (n = 5,012) for at least 6 months were enrolled in the study. Participants diagnosed with AF at baseline (n = 74) and those without SRH records (n = 61) were excluded, resulting in a final population of 9,895 participants.

A myriad of comprehensive health examinations, detailed on-site interviews, and meticulous laboratory tests were conducted during the baseline visit to a tertiary hospital. Six serial reassessments, following the entire cohort protocol, were performed through scheduled revisits every other year until 2014. All participants voluntarily enrolled in the study and provided written informed consent at the baseline assessment and each follow-up visit. The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Korean National Research Institute of Health and the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Hanyang University Medical Center (IRB no. HYUH 2017-12-033).

Assessment of lifestyle and medical history, physical examination, and laboratory tests

Well-trained investigators conducted comprehensive on-site interviews, collected critical lifestyle and clinical data, and performed physical examinations at tertiary hospitals during each visit. A structured questionnaire was used to obtain data on smoking, alcohol intake, education level, and specific medical conditions, such as HTN, DM, dyslipidaemia, cerebrovascular disease, CAD, and heart failure. Higher education was defined as obtaining a college degree or higher. The type and duration of physical activity were assessed using detailed questionnaires and quantified using estimated daily metabolic equivalent task scores. Blood pressure was measured by trained examiners using a mercury sphygmomanometer positioned at the level of the heart. Measurements were taken at least twice with the participant in a sitting position, and the results were averaged. If a blood pressure difference of ≥ 5 mmHg was observed between the two measurements, a third measurement was taken, and the last two measurements were averaged. WC was measured at the midpoint between the lowest rib and iliac crest at the end of expiration in a standing position.

Blood samples were collected after overnight fasting and analysed to determine the lipid profiles, haemoglobin A1c levels, white blood cell counts, and CRP levels using an automated analyser. Laboratory evaluations were performed in a single core clinical laboratory accredited and participating annually in inspections and surveys by the Korean Association of Quality Assurance for Clinical Laboratories. Blood concentrations of glucose, total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol, and triglyceride were measured using the enzyme method (ADVIA 1650 and ADVIA 1800; Siemens Healthineers). Low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol levels were calculated using the Friedewald formula25. CRP was measured using a turbidimetric assay method (ADVIA 1650 and ADVIA 1800; Siemens Healthineers). HTN was defined as a diagnosis of HTN made by a physician or the regular use of antihypertensive medications. DM was defined as a diagnosis of DM by a physician, regular use of antidiabetic medications, or a haemoglobin A1c level of ≥ 6.5%. Dyslipidaemia was defined as a diagnosis of dyslipidaemia by a physician, the regular use of statin without a history of cardiovascular disease or DM, or the presence of at least one of the following abnormal laboratory test results: total cholesterol level ≥ 240 mg/dL, triglyceride level ≥ 150 mg/dL, or HDL cholesterol level < 45 mg/dL.

Assessment of self-rated health

Participants were asked to evaluate their overall health by responding to the question, ‘How do you generally perceive your health?’ The responses were initially divided into five categories: ‘very poor’, ‘poor’, ‘fair’, ‘good’, and ‘very good’. Due to the relatively small numbers of participants who responded ‘very poor’ (n = 411) and ‘very good’ (n = 154), we reclassified the responses into three categories: ‘poor (very poor/poor)’ SRH (n = 3,380), ‘fair’ SRH (n = 3,521), and ‘good (good/very good)’ SRH (n = 2,994).

Standard 12-lead ECG and identification of AF

Standard 12-lead ECG (GE Marquette MAC 5000®, GE Marquette Inc., Milwaukee, WI, USA) was performed in all participants at baseline and during every revisit. All ECG tracings were recorded at a paper speed of 25 mm/s and an amplitude of 0.1 mV/mm. The results were interpreted by a cardiologist and coded according to the Minnesota code classification system. AF was identified either through the presence of AF on a 12-lead ECG or a self-reported history of AF using a questionnaire administered by a physician before the baseline visit or during follow-up visits. The Minnesota codes 8-3-1, 8-3-2, 8-3-3, and 8-3-4 were used to classify AF. Newly developed AF was defined as the first identification of AF between visits. The date of new AF development was defined as the date when AF was first detected on ECG or when it was diagnosed by a physician.

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics of the participants were compared between the groups. One-way analysis of variance was used for analysing continuous variables, such as BMI, WC, and LDL-cholesterol levels, while Pearson’s chi-square test was used for analysing categorical variables, including sex, comorbidities, and smoking history. Post-hoc analyses using Bonferroni correction were used to perform multiple comparisons. For continuous variables with a skewed distribution, comparisons between groups were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of the distribution of continuous variables.

All variables had approximately 1% missing values. The missing values of individual variables ranged from 0 to 4.9%. Among the covariates in the multivariate regression models, the missing values of individual variables ranged from 0 to 1.04% (Supplementary Fig. S1). Rather than excluding cases with missing data, multiple imputations were performed using a bootstrap expectation-maximization algorithm26. Five possible imputed datasets were generated. The average value was used for continuous variables, while the most frequent value was adopted for categorical variables.

The associations between SRH and incident AF were evaluated using a CPH model adjusted for age, sex, residence, education, BMI, physical activity, comorbidities (including HTN, DM, heart failure, dyslipidaemia, MI, non-MI CAD, asthma, and chronic lung disease), smoking status, alcohol consumption, and laboratory data (including LDL cholesterol levels and CRP levels. The factors associated with the ‘poor’ SRH group were analysed using logistic regression analysis. To determine whether SRH provided an additional predictive value for incident AF when combined with conventional risk factors, we developed prediction models for new-onset AF with and without the SRH variable using multivariate CPH models. The goodness of fit of these prediction models was estimated using Harrell’s C-index and Akaike information criterion (AIC). Harrell’s C-indices were compared using the method proposed by Haibe–Kains et al.27. The linear predictors identified using multivariate CPH models were employed as risk predictors for the C-index estimation. A difference of > 10 between the two AIC values was considered significant.

To evaluate the impact of reclassifying SRH responses from five to three categories based on the survey results, we performed a sensitivity analysis using a Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and a multivariate CPH model with the original five-category SRH responses. Due to the small number of ‘very good’ responses, the ‘good’ response was used as a reference when calculating the coefficients in the multivariate CPH model.

All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software R-4.3.2 (R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and its packages ‘tableone’, ‘rms’, ‘Amelia’, ‘survival’, ‘BiocManager’, and ‘survcomp’ in RStudio-2023.12.1, Build 402 (RStudio Team, RStudio Inc., Boston, MA, USA). A P value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Benjamin, E. J. et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2019 update: a Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 139, e56–e528. https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000659 (2019).

Li, X., Tse, V. C., Au-Doung, L. W., Wong, I. C. K. & Chan, E. W. The impact of ischaemic stroke on atrial fibrillation-related healthcare cost: a systematic review. Europace. 19, 937–947. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euw093 (2017).

Mavaddat, N., Parker, R. A., Sanderson, S., Mant, J. & Kinmonth, A. L. Relationship of self-rated health with fatal and non-fatal outcomes in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 9, e103509. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0103509 (2014).

van der Linde, R. M. et al. Self-rated health and cardiovascular disease incidence: results from a longitudinal population-based cohort in Norfolk, UK. PLoS One. 8, e65290. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0065290 (2013).

Ko, H. L., Min, H. K. & Lee, S. W. Self-rated health and the risk of incident chronic kidney disease: a community-based Korean study. J. Nephrol. 36, 745–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-022-01518-3 (2023).

Kim, S. M. et al. Association of chronic kidney Disease with Atrial Fibrillation in the General Adult Population: a Nationwide Population-based study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 12, e028496. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.122.028496 (2023).

Abu, H. O. et al. Multimorbidity, physical frailty, and self-rated health in older patients with atrial fibrillation. BMC Geriatr. 20, 1–11 (2020).

Kornej, J., Börschel, C. S., Benjamin, E. J. & Schnabel, R. B. Epidemiology of Atrial Fibrillation in the 21st Century: Novel methods and New insights. Circ. Res. 127, 4–20. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.120.316340 (2020).

Misra, S. et al. Outcomes of a remote Cardiac Rehabilitation Program for patients undergoing Atrial Fibrillation ablation: pilot study. JMIR Cardio. 7, e49345. https://doi.org/10.2196/49345 (2023).

Lee, Y. et al. Single and persistent elevation of C-reactive protein levels and the risk of atrial fibrillation in a general population: the Ansan-Ansung Cohort of the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study. Int. J. Cardiol. 277, 240–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.10.070 (2019).

Uchino, B. N. et al. Self-rated health and inflammation: a test of Depression and Sleep Quality as mediators. Psychosom. Med. 81, 328–332. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000683 (2019).

Sanna, T. et al. Cryptogenic stroke and underlying atrial fibrillation. N Engl. J. Med. 370, 2478–2486. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1313600 (2014).

Finn, L., Young, T., Palta, M. & Fryback, D. G. Sleep-disordered breathing and self-reported general health status in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. Sleep. 21, 701–706 (1998).

Balaj, M. Self-reported health and the social body. Soc. Theor. Health. 20, 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-020-00150-0 (2022).

Lunde, E. D. et al. Socioeconomic position and risk of atrial fibrillation: a nationwide Danish cohort study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 74, 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2019-212720 (2020).

Jylha, M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc. Sci. Med. 69, 307–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.013 (2009).

Emmelin, M. et al. Self-rated ill-health strengthens the effect of biomedical risk factors in predicting stroke, especially for men–an incident case referent study. J. Hypertens. 21, 887–896 (2003).

May, M., Lawlor, D. A., Brindle, P., Patel, R. & Ebrahim, S. Cardiovascular disease risk assessment in older women: can we improve on Framingham? British women’s heart and health prospective cohort study. Heart. 92, 1396–1401 (2006).

Rahman, F., Kwan, G. F. & Benjamin, E. J. Global epidemiology of atrial fibrillation. Nat. Reviews Cardiol. 11, 639–654 (2014).

Schnabel, R. B. et al. 50 year trends in atrial fibrillation prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and mortality in the Framingham Heart Study: a cohort study. Lancet. 386, 154–162 (2015).

Chugh, S. S. et al. Worldwide epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: a global burden of Disease 2010 study. Circulation. 129, 837–847 (2014).

Lee, S. R., Choi, E. K., Han, K. D., Cha, M. J. & Oh, S. Trends in the incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation and estimated thromboembolic risk using the CHA2DS2-VASc score in the entire Korean population. Int. J. Cardiol. 236, 226–231 (2017).

Lee, Y. et al. Association between insulin resistance and risk of atrial fibrillation in non-diabetics. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 27, 1934–1941. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487320908706 (2020).

Kim, Y. & Han, B. G. Cohort Profile: the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES) Consortium. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 1350. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyx105 (2017).

Friedewald, W. T., Levy, R. I. & Fredrickson, D. S. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein choleterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 18, 499–502 (1972).

Honaker, J., King, G., Blackwell, M. & Amelia, I. I. A program for Missing Data. J. Stat. Softw. 45, 1–47. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v045.i07 (2011).

Schroder, M. S., Culhane, A. C., Quackenbush, J. & Haibe-Kains, B. Survcomp: an R/Bioconductor package for performance assessment and comparison of survival models. Bioinformatics. 27, 3206–3208. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr511 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants and research staff of the Institute of Human Genomic Study at the Ansan Hospital of Korea University.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have agreed to the content of this manuscript and its submission to Scientific Reports. In the case of acceptance of the manuscript, the copyright will be transferred to Scientific Reports. All data are fully available without restriction and all relevant data is included within the paper. As a corresponding author, I sign this letter on behalf of all coauthors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

†Yonggu Lee and Jae Han Kim have contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, Y., Kim, J. & Park, JK. Self-rated health and the risk of incident atrial fibrillation in general population. Sci Rep 14, 24651 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76426-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76426-6