Abstract

Scientific insights into water photolysis and radiolysis are essential for estimating the direct and indirect effects of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) damage. Secondary electrons from radiolysis intricately associated with both effects. In our previous paper, we simulated the femtosecond (1 × 10− 15 s) dynamics of secondary electrons ejected by energy depositions of 11−19 eV into water via high-energy electron transport using a time-dependent simulation code. The results contribute to the understanding of simple “intra-spur” chemical reactions of tree-body chemical species (hydrated electrons, hydronium ion and OH radical) in subsequent chemical processes. Herein, we simulate the dynamics of the electrons ejected by energy depositions of 20−30 eV. The present results contribute to the understanding of complex “inter-spur” chemical reactions of the multi-body chemical species as well as for the formation of complex DNA damage with redox site and strand break on DNA. The simulation results present the earliest formation mechanism of an unclear multi-body chemical species spur when secondary electrons induce further ionisations or electronic excitations. The formation involves electron–water collisions, i.e. ionisation, electronic excitation, molecular excitation and elastic scattering. Our simulation results indicate that (1) most secondary electrons delocalise to ~ 12 nm, and multiple collisions are sometimes induced in a water molecule at 22 eV deposition energy. (2) The secondary electrons begin to induce diffuse band excitation of water around a few nm from the initial energy deposition site and delocalise to ~ 8 nm at deposition energies ~ 25 eV. (3) The secondary electron can cause one additional ionisation or electronic excitation at deposition energies > 30 eV, forming a multi-body chemical species spur. Thus, we propose that the type and density of chemical species produced by water radiolysis strongly depend on the deposition energy. From our results, we discuss formation of complex DNA damage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fundamental studies on water photolysis and radiolysis are essential for understanding deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) damage in radiation biological effects, because the human body mostly comprises water. These scientific insights are particularly valuable for analysing the formation of clustered or multiple DNA damage, which is believed to induce biological effects, such as cell death, mutation induction or carcinogenesis1,2,3. The complexity of DNA damage clustering via direct and indirect effects depends on the density of radiolytic chemical species produced by energy deposited around DNA. In addition to the direct and indirect effects, previous studies reported that shock wave generated by ion irradiation of a living system was also involved in DNA damage4,5. The direct effect indicates that DNA damage results from energy deposited by primary radiation and ionised secondary electrons via atomic interactions, such as ionisation or electronic excitation. Meanwhilst, the indirect effect indicates that DNA damage results from the chemical reaction via thermal diffusion of the chemical species (e.g., hydroxyl radical (•OH) and hydrated electron (e− aq)) produced by the radiolysis of a living system. Therefore, it is essential to investigate the correlation between energy deposition and radiolytic chemical species.

Experimental photolysis and pulse radiolysis techniques have been developed to measure the fast reactions of chemical species resulting from laser or high-energy electron irradiation in the picosecond (ps) order6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. Monochromatic short-pulse lasers allowed the measurement of ultrafast phenomena on the femtosecond (fs) order. These kind of experiments have advanced studies on the formation of pre-hydrated electron (e− pre) and e− aq formations19,20,21,22,23. In recent years, combining liquid jet and mass spectrometry has also made it possible to measure the cation and anion yields from heavy ion irradiation in aqueous solutions24. Although advances in these experimental techniques have led to the accumulation of scientific data for various chemical species, the inhomogeneous spatial distributions of the initial chemical species remain controversial.

When water is irradiated with a high-energy electron, ionisations and electronic excitations considerably occur, inducing numerous single spurs inhomogeneously distributed along the electron tracks in the water. When ionisation is induced, a single spur primarily comprises three chemical species (•OH, hydronium ion (H3O+) and e− aq). In this study, we noted that the track indicates the long-distance trajectory of the incident electron and the spur indicates the spatial distribution with nanometer size of the secondary electrons produced by ionisation. In the period up to 100 ps, these chemical species in the spur react with each other (intra-spur reaction). Further down to the nanosecond (ns) order, chemical reactions between the expanding single spurs (inter-spur reaction) are induced within 100 ns, and the concentrations of the chemical species become spatially homogeneous9. These timescales depend on the chemical species’ diffusion coefficients and reaction rates and the spur radius and inter-spur distance. Even with modern measurement techniques, it is challenging to measure the spur radius and inter-spur distance by experiments directly.

To solve the scientific issues, the inter-spur distances have been simulated using the Monte Carlo code (MCC)1,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34 (e.g. Kyushu University Radiobiology Unit Code (KURBUC)1,28,29, TRACk structure of Electrons in Liquid water (TRACEL)26, TRACELE27, RITRACKS30, PARTRAC31, Geant4-DNA32 and Particle and Heavy Ion Transport code System (PHITS)33,34). Issues remain regarding the spur radius, which requires calculations for electron thermalisation until a few 100 fs and electron delocalisation around 10 nm. Recently, Geant4-DNA and PHITS enabled the electron deceleration calculation down to a few eV. However, conventional MCCs typically set the cut-off energy for electron deceleration at 7−10 eV35,36,37, making the evaluation of the spar radius challenging. Therefore, the spur radius must be modelled based on the experimental results of photo-ionisation36,37,38,39.

Therefore, Therefore, we developed a dynamic MCC for the physical process (dmcc_phys) consisting of Monte-Carlo (MC), molecular dynamics (MD) methods and database for electron impact cross sections that allows the calculation of the spur radius and inter-spur distances using a time-dependent simulation40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48. This code does not require setting the electron cut-off energies. We qualitatively revealed the electron deceleration delocalisation–relocalisation and hydration mechanisms resulting from a 12.4 eV energy deposition on water47 and indicated that our estimated spur radius correlates with the experimentally based estimation value16,47. We further studied three-body single spurs (•OH, H3O+ and e− aq) induced by deposition energies of 11−19 eV48. In a living cell, chemical reactions via the chemical spices will form many isolated DNA lesions, which can be easily repaired. However, clustered DNA damage, which contains multiple lesions within 10 base pairs (i.e., 3.4 nm), will slightly be formed via the chemical species of the multi-body chemical species spur, which comprises more than three chemical species (i.e., •OH, H3O+ and e− aq). Advanced knowledge of multi-body chemical species spur formation is needed when applying it to biological effects because clustered DNA damage strongly inhibits enzymatic repair49,50,51,52,53.

This study investigates the fs dynamics of secondary electrons produced by 20−30 eV deposition energy to clarify the earliest formation process of multi-body chemical species spurs using dmcc_phys. This study focuses on the dynamical simulation of only secondary electrons from an ionisation site (Fig. 1). We show the simulation results of the electron spatial distributions, collision frequency distributions in the spurs and the energy dependence of the mean collision frequency and spur radius. These results provide significant insights for interpreting the mechanisms of clustered DNA damage induction.

Methods

First, we briefly describe the features of our code. We proposed the physical code, dmcc_phys, in 201440. In the earliest development, we used electron impact cross-sections for gas-phase water40. In 2015, we reported molecular excitation cross-sections for liquid-phase water41 and updated ionisation and electronic excitation cross-sections for liquid-phase water42. We successfully demonstrated electron deceleration in extremely low-energy regions on the order of 10− 3 eV42, showing that the electron energy distributions asymptotically approach the Maxwellian (300 K bulk water) using momentum transfer and molecular excitation cross-Sects42,47,48. Using the dmcc_phys, we proposed a new formation mechanism for DNA damage involving e− pre.43,44,45 In the study45, we indicated a possibility that the clustered DNA damage generated by the mechanism cannot be removed.

Before 2018, we generated secondary electrons at the site where ionisations (1b1, 3a1, 1b2, 2a1 and 1a1) occur45. The latest dmcc_phys enables the simulation of electron dynamics induced from ionisations and electronic excitations (A1B1, B1A1, Rydberg (A + B), Rydberg (C + D), diffuse band and collective excitations)46. Furthermore, the dielectric response of water was calculated using Fourier transformation of the complex dielectric function of water46,47. These improvements led to successful calculations of the initial e− aq yield for the water radiolysis46 and the electron spatial distribution for the water photolysis47.

We facilitate understanding this calculation method by briefly describing the differences between the conventional MCC and dmcc_phys. The MCC follows the time-independent Monte Carlo (MC) method to simulate electron motion in water25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. Whereas the electron cut-off energy of arbitrary constant must typically be set in the MCC28,35, dmcc_phys follows the time-dependent MC and molecular dynamics (MD) methods to output the spatial and energy distributions of secondary electrons at each time42,43,44,45,46,47,48. Therefore, it is necessary to set the cut-off time in our dmcc_phys. The cutoff time is the time when the energy distribution of secondary electrons is close to Maxwellian of 300 K46,47,48. Our code can simulate the dynamical and collisional motions of the secondary electrons in the long-range Coulombic field created by the parent cation from moment to moment. The shielding of this Coulombic field along the dielectric response simulates the hydration process46,47,48. Especially, this hydration model revealed time evolution with the deceleration, thermalisation, precursor-hydration and hydration of electrons generated by the water photolysis47. The cross-section, time-dependent MC and MD methods, simulation setup and flowchart of our code are briefly described in the section below.

(a) Dielectric function calculated using previously reported fitting parameters26. (b) Energy loss function (ELF) calculated using previously reported fitting parameters (bark blue)26. ELF measured by Hayashi et al. (red circles)58. (c) Electronic excitation cross-sections: (1) A1B1 excitation (8.4 eV); (2) B1A1 excitation (10.1 eV); (3) Rydberg (A + B) excitation (11.25 eV); (4) Rydberg (C + D) excitation (11.93 eV); (5) diffuse band excitation (14.1 eV); (6) collective excitation (21.4 eV). The energy in parentheses represents the mean value of the transition energy56. (d) Ionisation cross-sections: (7) 1b1 ionisation (10.9 eV); (8) 3a1 ionisation (13.5 eV); (9) 1b2 ionisation (17.0 eV); (10) 2a1 ionisation (26.3 eV); (11) 1a1 ionisation (533 eV). The energy in parentheses represents the mean value of the transition energy57. The collective excitation depicted as (6) in Fig. 2c, which is the highest cross-section, was assigned by Paretzke et al.56. , however, physical interpretation for the collective excitation is controversial, in general, not widely accepted.

Cross-sections

The inelastic–scattering cross-sections of liquid water can be calculated using the energy loss function (ELF), obtained from the complex dielectric function54. Experimental results of the complex dielectric function of water55 and the fitting parameters of the complex dielectric function26 have been reported. Figure 2a and b show the complex dielectric function and ELF results, respectively. The ELF represents the energy absorption efficiency of water, with a maximum of approximately 21.4 eV55. The absorption efficiency decreases monotonically for the high-energy region above 22 eV in Fig. 2b. First, we present electronic excitation and ionisation cross-sections. The cross-sections σ were calculated using σ = 1/(λN), where λ and N are the mean free path and molecular density (3.318565 × 1022 molecules/cm3), respectively. Each ionisation and electronic excitation level was assigned according to two literature56,57. We used 11 fitting parameter sets of the complex dielectric function, ε(0,ω’), as a function of energy transfer ω’26, and calculated each inverse mean free path λ−1 from Ashley’s formula54,

where

where E is the kinetic energy of an electron interacting with liquid water. Figure 2c and d show the electronic excitation and ionisation cross-sections, respectively. Deposition energies of 20−30 eV to water eject secondary electrons with kinetic energies of 10−20 eV when subtracting the ionisation energy (10.9 eV)57, resulting in additional collision events by the secondary electrons. The diffuse band and collective excitation cross-sections highlighted in red exceed 1 × 10− 18 cm2 in the 10–20 eV energy region in Fig. 2c. It is thought that secondary electrons with a few 10 eV can induce these excitations. A further increase in the deposition energy will also induce 3a1 and 1b2 ionisations, which have relatively high cross-sections (Fig. 2d). We used the complex dielectric function reported by Heller et al.55. In 2015, Hayashi et al. also reported the function that may be accurate58. We also plotted the data reported by Hayashi et al.58. to compare Heller’s data55 in Fig. 2b. There is a conspicuous discrepancy particularly in the energy region above 20 eV. This difference will affect the values of the ionization and electronic excitation cross sections. Since the main purpose of this study was not to calculate the cross sections, the calculation would be a future work.

The electron impact cross-sections for elastic scattering and molecular excitations are essential for simulating secondary electron motion. Figure 3a shows the intra-molecular vibrational excitation cross-sections. We used the amorphous ice data to obtain the cross-sections of the condensed phase59. The data were connected by scaling the water vapour data60 to the amorphous ice data because no data below 1.7 eV have been reported. Figure 3b shows the inter-molecular vibration excitation cross-sections. In our previous study41, the data were calculated with optical approximation using the ELF of liquid water61. However, since the approximation cannot reproduce the resonance structure, the data above 1.7 eV were connected by scaling the amorphous ice data to our data. Figure 3c shows the rotation excitation cross-sections for liquid water. The data were calculated with optical approximation using the ELF of liquid water in our previous study41. The rotation excitation cross-section for water vapour60 is also shown for comparison. We also show the elastic scattering, total molecular excitation and total ionisation and electronic excitation cross-sections in Fig. 3d.

(a) Intra-molecular vibration excitation cross-sections, red solid line: our data, ☐: water vapor59 ◇: amorphous ice60, (b) inter-molecular vibration excitation cross-sections, red solid line: our data, ◇: amorphous ice60, (c) rotation excitation cross-sections, red solid line: our data, 〇: water vapor59 and (d) red solid line: total molecular excitation cross-section, blue solid line: total ionization and electronic excitation, black solid line: elastic scattering.

Moliere’s elastic scattering cross-section was used62. The differential and integral cross-sections, q(θ) and σelas, are represented by the following formulas:62

and

where the screening parameter, \(\:\eta\:\), is given by

where θ is the scattering angle, the effective atomic number Z of the water molecule was assumed to be 7.42, the classical electron radius re = 2.8179 × 10− 13 cm, β is the ratio of the velocity of the electron to the velocity of light, τ = E/m0c2 and E, m0 and c are the electron energy, electron rest mass, and velocity of light, respectively,

ηc = 1.198 for E < 50 keV,

\(\:=\:1.13+3.76{\left(\frac{Z}{137\beta\:}\right)}^{2}\) E > 50 keV.

When elastic scattering is induced, no energy change occurs in the relative motions of an electron and a water molecule; however, the energy for the motion of the centre-of-mass system changes63,64. This phenomenon is evaluated using the momentum transfer cross-section, σmom, from the differential cross-section, q(θ), of elastic scattering63,64,

Using the σmom of Eq. (4) and the integral elastic scattering cross-section σelas of Eq. (3), the energy transfer is given as46,47,48,63,64

where m and M are the mass and Ee and Emol are the kinetic energies of the electron and water molecules, respectively. Emol was sampled from the Maxwellian of 300 K bulk water. When Ee > Emol, the electrons provided little energy to the water, whereas when Ee < Emol, the electrons received some energy from the water. After the electrons emitted from water molecules are sufficiently decelerated by molecular excitations, the electron energy is mainly determined by the Eq. (5). Therefore, the energy decreases and increases repeatedly by momentum transfer due to elastic scattering between electrons and water until the cut-off time. Thus, our code does not have a specific lower limit in electron energy and provides an energy distribution approaching to a Maxwellian. Finally, the electron kinetic energy distribution approaches the Maxwellian of 300 K bulk water46,47,48, although ΔE is approximately a few µeV.

Since the conventional MCC (physical code) cannot simulate electron deceleration processes below a few eV, the spur radius must be modelled based on the experimental results of photo-ionisation36,37,38,39. In fact, these MCCs correct for the initial position of the e − aq in the physicochemical process65. The electron deceleration process is typically categorized as a physicochemical process. Our code consists of the MC and MD methods. Same as the conventional MC codes25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34, we also implemented the cross sections shown in Figs. 2 and 3 into our code. This implementation allows for electron deceleration calculation in water (physicochemical process), resulting in connections to chemical processes. The MD method allows for the electron relocalisation calculation to the parent cation46,47,48.

Time-dependent MC and MD methods

The conventional MCC gives the one-step distance of an electron moving to the next collisional position in the water as Δs = −λln(k); k is a uniform random number. Our code assumes that collisions between electrons and water are induced if the following conditions are satisfied:46,47,48

where Δs = vΔt, where v is the absolute value of the electron velocity, and Δt is the time step set to 1 attosecond (1 × 10− 18 s). After the electron collision coordinate is determined, the collision process is identified and sampled from the ratio of each cross-section. From Fig. 3d, the inelastic–scattering cross-sections for the rotation and inter- and intra-molecular vibration modes are close to zero with decreasing electron energy; however, the elastic scattering cross-section has a considerable finite value. Thus, the mean free paths λ of extremely low-energy electrons have noticeably short ranges.

When elastic scattering is induced, the scattering angle is sampled from the differential cross-section q(θ) in Eq. (2). When molecular excitation is induced, it is assumed that the scattering angle does not change since the frequency of molecular excitation is considerably less than that of elastic scattering (Fig. 3d). When ionisation or electronic excitation is induced, the scattering angles θp and θs for primary and secondary electrons are given by the energy and momentum conservation laws, respectively, as shown in Eqs. (7),26

where E1 is the kinetic energy of the colliding electron, and the initial kinetic energy E2 of the generated electron is sampled from the ELF (Fig. 2b). The azimuthal angle φ is sampled from a uniform random number, determining the post-collision velocity vector.

We assumed that electrons and cations are finite-size particles of radius a with negative and positive charges (finite-size particle model)46,47,48. The particle radius was 0.099 nm to reproduce the lowest ionisation energy of 10.9 eV57, and a minimum position of the potential energy (–10.9 eV) was allocated at the origin. When the potential of the cation is expressed in spherical coordinates, it can be expressed as,

where e is the elementary charge, and ε = ε0 × εr(t). ε0 is the dielectric constant of a vacuum and εr(t) is the dielectric response reported in our previous papers46,47. This result causes the potential energy to change with time evolution, as reported previously46,47. Figure 4 (a) and (b) show the potential energy and an illustration of potential energy-shielding by the polarisation effect. In conventional MCCs27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35, the kinetic energy of the secondary electron is obtained by subtracting the ionisation energy from the deposition energy. However, in our code, a secondary electron begins to move with its deposition energy (20–30 eV) from the position (origin) of a potential minimum. When a new ionisation or electronic excitation occurs, the time of dielectric response is 0 and begins anew. The dynamical and collisional motion of the secondary electron in the dynamical Coulombic field in water can be calculated by solving the Newtonian equation in Eq. (9) and the change in the velocity vector due to collisions in Eqs. (2) and (7):

where

where F is the force between the electron and the cation, and m is the electron mass. The electron coordinate is given by x, r (= |r|) is the relative distance between the electron and the cation, and v is the velocity vector of the electron. Chemical species, such as H3O+ and •OH, are assumed to be immobile on the order of fs.

Charges generated in water are shielded by the polarization effect. The dielectric response which shields the charge is very fast in water47, and the electron-water collision considerably delays the recombination time between the electrons and the parent ion. For these reasons, many ionised electrons become delocalized, and some electrons distributed within 1 nm of the parent ionic core can be relocalised during a few 100 fs46,47,48. Initial and additional electrons do not relocalise unless they reach a region within 1 nm of another parent ionic core. The possibility of this process would be not high. Therefore, we considered only the two-body Coulombic interaction between the electron and its parent ion to reduce the simulation cost. Under this assumption, we have successfully estimated the initial yield of e− aq from the ratio of delocalized to relocalised components of ionised electrons generated by a low-density electron irradiation field in our previous study46. For much higher-density radiation field, on the other hand, the multi-body Coulombic interaction needs to be taken into account.

Code validation

Time-dependent density function theory (TDDFT), following quantum theory, is a powerful tool for studying the electronic states of molecules. However, the number of target molecules is limited to one or two and the computation time is about 10 fs66, making it difficult to analyse the spur formation field in which many molecules are involved in the process. Therefore, we have developed our code that is a good analyser handling a space of about 10 nm and a time of about several hundred fs in water. To date, we validated our code to compare experimental data. First, we calculated the thermalisation lengths to compare the experimental data67 of low energy electrons ejected by photo-injections into electrode in water46. Second, we calculated the spur radius to compare the experimental data11,12,13,14,15,16 for water photolysis47,48. In those comparisons, we reproduced the experimental data, validating our MC method. Third, we also estimated the initial yield of e− aq from the ratio of delocalised to relocalised components of ejected electrons in 10 keV electron irradiation to water46, validating our MD method which that allows electron relocalisation.

Simulation setup

In this study, the initial coordinate of deposited energy to water is assumed to be at the origin (0, 0, 0). All deposition energy Edep is converted to the kinetic energy E of the initial secondary electron at the origin. The initial velocity vector of the electron with the kinetic energy is set in the z-axis direction. The Coulombic potential of the cation immediately slows down the initial secondary electrons ejected from the origin45. The secondary electrons induce ionisation and electronic excitations to the surrounding water molecules around parent cations and become thermalised–delocalised and relocalised by elastic scattering and molecular excitations46,47,48. H3O+ and •OH are at the initial and additional energy deposition sites. The dielectric response gradually shields the Coulombic force of the parent cation47. Although this shielding effect becomes stronger as time passes in the order of picoseconds, this Coulombic force might cause electrons to relocalise into parent cations within a few 100 fs46,47,48. When the secondary electrons are relocalised, chemical species, such as H• + •OH rather than H3O+ + •OH + e− aq, are produced at the initial or additional energy deposition sites17,46,47,48. Our simulations were performed based on uniform random numbers in the MC, and the number of calculation trials was adapted to reach a statistical uncertainty of much less than 1%.

Flowchart

This subsection shows a flowchart of conventional MCCs and dmcc_phys for multi-body chemical species spur formation to clarify the different calculation algorithms between the MCCs and dmcc_phys. Figure 5(a) shows a flowchart of conventional MCCs1,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35, (1) where the inputs to the MCC are the number of trials (N), the deposition energy (Edep) and electron cut-off energy (Ecut). The initial kinetic energy of the initial secondary electron was determined with Edep − Ie (ionisation energy; 10.9 eV)57. (2) In the kinetic method, an electron is transported by Δs = −λln(k).26 (3) In the MC method, the energy loss ΔE of the electrons and the number of generated electrons n2nd are obtained. (4) Processes (2) and (3) are repeated until the initial secondary electron energy reaches the cut-off energy. (5) Then, for the additional secondary electron generated, repeat steps (2)–(4) in the same manner as for the initial secondary electrons. (6) Once these calculations are complete, move on to the next trial, J = J + 1. (7) All calculations are completed when the statistical uncertainties in the results are sufficiently small. In a conventional MCC, the calculated results depend on the cut-off energy. Therefore, the calculated results include time uncertainties due to energy identification.

Figure 5(b) shows the flowchart of our code (1), where the inputs to our code are the number of trials (N), the deposition energy (Edep), the cut-off time (tcut) of the calculation and the time step Δt (1 attosecond). (2) In the MD method, the dynamic behaviours of the initial and additional secondary electrons are simultaneously solved for each time step Δt following Eq. (9). (3) In the time-dependent MC method, electron–water collisions are determined by Eq. (6). If a collision occurs, the electron energy loss ΔE and the number of generated electrons n2nd are obtained. (4) Process (3) is repeated for the number of n2nd. (5) After processes (2)–(4) are completed, we move on to the next time, t = t + Δt. Processes (2)–(5) are repeated until the cut-off time is reached. (6) Once these calculations are complete, move on to the next trial, J = J + 1. (7) All calculations are completed when the statistical uncertainty of the results is sufficiently small. In our code, the calculated result depends on the cut-off time. Therefore, the results include energy uncertainties due to time identification.

(a) Flowchart of conventional Monte Carlo codes (MCCs) for simulating an ejected electron generated by water photolysis or radiolysis, where ΔE is the energy loss. (b) Flowchart of dmcc_phys for simulating an ejected electron generated by water photolysis or radiolysis. Here, the initial kinetic energy of the ejected electron equals the deposition energy Edep. The velocity vector was determined using the Monte Carlo (MC) and molecular dynamics (MD) methods. MD allows electron relocalisation.

Results and discussions

First, we present the calculation results of electron spatial and collision frequency distributions at 22, 25, 27 and 30 eV deposition energies. Second, we show the energy dependence of the mean collision frequency and spur radius at 20–30 eV deposition energies. From these results, we finally discuss the formation mechanisms of clustered DNA damage.

Electron spatial distribution

When high-energy electron transport deposits 20–30 eV energy in water, the ejected secondary electrons can immediately induce ionisation or electronic excitation. After induction, the secondary electrons become thermalised–delocalised and relocalised by molecular excitations and elastic scattering. In our previous study47, we demonstrated water photolysis at a deposition energy of 12.4 eV, indicating that the inter-molecular vibration mode is preferentially responsible for electron delocalisation and pre-hydration, whereas the rotation mode and elastic scattering are responsible for electron thermalisation and hydration. The simulation results indicated that e− aq forms after 300 fs or more at a deposition energy of 12.4 eV47. However, out latest study found that the thermalisation time increases as the deposition energy increases, and the time is ~ 500 fs at deposition energies of 17–19 eV48. In this study, the electron cut-off time was 500 fs. Under these conditions, we confirm that the electron-energy distributions sufficiently approach the Maxwellian of 300 K.

Figure 6a–d depict the calculated results of the electron spatial distributions at 500 fs at 22, 25, 27 and 30 eV deposition energies, respectively. Calculation 1 in Fig. 6 shows the spatial distribution of the initial secondary electrons ejected by the initial energy deposition (blue line). Calculation 2 shows the spatial distribution of the additional secondary electrons newly produced by the collision of the initial secondary electrons (red line). Calculation 3 shows the spatial distribution of the sum of all electrons (light blue line). The distance on the horizontal axis indicates the relative distances between the initial electron and its parent ion, and between the additional electron and its parent ion. The positions of initial and additional ionisation are different. To indicate the absolute positions of the initial and additional secondary electrons separately or together, we need the support of Fig. 7 (next paragraph) which will provides information on the position of the additional secondary electron generation. The horizontal axis represents the relative distance from the ionic core of each parent cation. At 22 eV deposition energy, the number of additional secondary electrons is low (calculation 2 in Fig. 6a). Most additional secondary electrons are distributed in a very narrow region within 1 nm of the ionic core of the parent cations, indicating that they relocalise to the parent cations. Although some initial secondary electrons also relocalised to the parent cations, most delocalise to ~ 10 nm, forming a spur (calculation 1 in Fig. 6a). Production yields of additional secondary electrons gradually increase as the deposition energy increases above 25 eV. The electrons delocalise to ~ 5 nm from the ionic core of the new parent cations, whereas the relocalisation of those electrons decreases (calculation 2 in Fig. 6a–d). The initial secondary electrons delocalise to ~ 8 nm from the ionic core of parent cations above 25 eV (calculation 1 in Fig. 6b). In other words, when the deposition energy is above 25 eV, a multi-body chemical species spur forms and the spur radius decreases above 25 eV.

Spatial distributions of electron numbers at deposition energies of (a) 22, (b) 25, (c) 27 and (d) 30 eV at 500 fs. Calculation 1 shows the distribution of only the initial secondary electrons. Calculation 2 shows the distribution of additional secondary electrons. Calculation 3 shows the distribution of all electrons. The horizontal axis represents the relative distance from the ionic core of each parent cation. The distribution results are shown as spherical coordinates with a spatial mesh Δr = 0.1 nm. All-solid angle meshes ΔΩ in the Δr are integrated.

Collision frequency distribution

Figure 7(a) and (b) show the collision frequency distributions at deposition energies of 22 and 25 eV and 27 and 30 eV, respectively. The collision frequency considerably increases in the region of a few Å at 22 eV deposition energy (Fig. 7(a)). Secondary electrons are ejected from the bottom of the potential assumed by our model with kinetic energy corresponding to the deposition energy (Fig. 4a). The potential energy is still sufficiently deep in the region of a few Å. Therefore, it can be interpreted that the cation potential before the electron deceleration induces multiple collisions in a single water molecule. Chemical species, such as 2H3O+, •O• and 2e−, might be produced by double proton transfer via H2O2+ induced by multiple collisions in a single water molecule. However, from Fig. 6(a) at 22 eV deposition energy, initial or additional secondary electrons are more likely to relocate to the parent cation when multiple collisions are induced. As the deposition energy is further increased, the rate of multiple collisions decreases because the time that electrons present in the molecule is shortened, and additional chemical species are generated in the region of a few nm from the parent cations, indicating multi-body chemical species spur formation.

(a) Collision frequency distribution of ionisation plus electronic excitation at 22 and 25 eV deposition energies. (b) Collision frequency distribution of ionization plus electronic excitation at 27 and 30 eV deposition energies. The distribution results are shown as spherical coordinates with a spatial mesh Δr = 0.1 nm. All-solid angle meshes ΔΩ in the Δr are integrated.

Spur radius

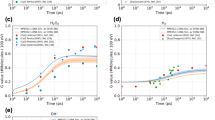

In our latest study48, we calculated the spur radius at deposition energies of 11–19 eV. From these calculated results and the experimentally based estimation values (8–12.4 eV) in the previous study11,12,13,14,15,16, we indicated that the spur radius generally increases linearly in the energy range. In this study, we first present the mean collision frequencies of the ionisations and electronic excitations induced by the initial secondary electrons in Fig. 8(a). Water is most likely to absorb the energy of 21.4 eV (Fig. 2(b)), and multiple collisions are sometimes induced by the induction of collective excitation at a deposition energy of 22 eV (Fig. 6(a) and 7(a)). However, additional ionisation or electronic excitations are gradually induced at several nm from the origin (Fig. 6(b) and 7(a)) above 25 eV deposition energy, and the initial secondary electrons finally delocalised to ~ 8 nm with many inductions of elastic scattering and molecular excitations (Fig. 6(b)). Here, diffuse band excitation with a mean transition energy of 14.1 eV (corresponding to the deposition energy of 25 eV minus the ionisation energy of 10.9 eV) can be induced, as described in the subsection (cross-section) of Methods (Fig. 2(c)). Our latest paper48 shows that electron relocalisation is small in diffuse band excitation induction, and electron delocalisation primarily produces H3O+, •OH and e−. As the deposition energy reaches 30 eV, at least one additional ionisation is induced, indicating that a multi-body chemical species spur is formed.

Figure 8b shows the spur radius in the energy range of 8–30 eV. The present results for 20–30 eV deposition energies were estimated from calculation 1 in Fig. 6. The experimentally based estimation values11,12,13,14,15,16 and our previous results48 are also shown in the energy region of 8–12.4 eV and 11–19 eV, respectively. Our results show that the spur radius reaches a maximum of ~ 12 nm at 24 eV. A further increase in deposition energy induces diffuse band excitation; consequently, the spur radius decreases to ~ 8 nm in the 24–27 eV energy region. One additional ionisation or electronic excitation is induced at approximately 30 eV, resulting in spurs of multi-body chemical species.

This work clarifies how the chemical species formed in the spurs change with increasing deposition energy. Figure 9(a) summarises the present results. A three-body spur is formed when the deposition energy is < 19 eV. A multi-collision spur is sometimes formed, and initial or additional secondary electrons are relocalised above 22 eV. When the deposition energy reaches 30 eV, multi-body spur formation is completed.

DNA damage

The damage sites induced by a spur within a 10 bps (i.e., 3.4 nm) are clustered DNA which are thought to be a major genetic effect, such as cell death or mutation induction. Even when the size of the clustering events is beyond 3.4 nm, they are categorized as “complex types of DNA damage” possibly causing the deleterious effect of cells depending on their complexities68,69,70. Here, we discuss the clustered DNA damage formation mechanism from our calculated results. Our study assumed that the initial secondary electron was emitted from DNA by deposition energy via high-energy electron transport in an aqueous DNA solution. Figure 9(b) schematically illustrates clustered DNA damage formation in a 10 base-pair segment for three energy deposition cases predicted by our results. The damage complexity is discussed based on our results integrated with previous experimental insights of the direct DNA oxidation by high-energy electrons71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80 as follows.

-

(1)

The deposition energy < 19 eV. When the deposition energy of DNA from the high-energy electrons is below 19 eV, a produced secondary electron is decelerated and finally formed e− aq distributes within 10 nm around the ionised DNA as revealed by present study. The positive charge generated on DNA is likely to move on guanine via hole transfer71,72,73 to form a guanine cation74, and then an oxidative base lesion, such as 8-oxo-guanine (8-oxo-G), is formed after deprotonation from the cation. The e− aq are thermally diffused, even though the frequency of e− aq arriving within 10 bps DNA would not be high. Once a e− aq reacts with the ionised DNA within 10 bps, a reductive base lesion, such as dihydrothymine (DHT) via thymine anion74, takes hold. Thus, clustered damage consisting of one oxidative base lesion (direct energy deposition to DNA) and one reductive base lesion (indirect action of e− aq).

-

(2)

The deposition energy ~ 22 eV. The ELF of water is most likely to absorb energy around 21.4 eV through radiation transport (Fig. 2(b)). The deposition energy on DNA causes multiple localised collisions, as shown in the multi-collision spur (~ 22 eV) in Fig. 7(a). If either the initial or additionally produced secondary electron relocalises to their parent cations, the electron may be recaptured the cation. On the other hand, if both electrons escape from the Coulomb field of the cations, they could be hydrated and thermally diffuse to interact with a DNA base with much higher frequency than the case of the deposition energy < 19 eV as described above. Consequently, these events may produce a more complex combination of an oxidative and one (or two) reductive base lesion(s). This model well consistent with previously experimental reports using fully hydrate plasmid DNA films. The pyrimidine base lesions, such as DHT, produced by γ-rays are 1.3 times larger than that for oxidative base lesion, such as 8-oxo-G75. This ratio is significantly enhanced to be over 2-fold for X-ray76 or He2+ ion77 and C5+,6+ and Ne8+,10+ ion irradiations78.

-

(3)

The deposition energy > 25 eV. When the deposition energy is above 25 eV, chemical species (•OH, e− aq and H3O+) are densely produced in the DNA neighbourhood (Figs. 6 and 7). These chemical species are thermally diffused and facilitate a multibody spur reaction around DNA. When •OH and e− aq approach within 10 bps DNA, they react with the DNA backbone and base, respectively74, resulting in single-strand breaks (SSBs) and reductive base lesions. Thus, a highly clustered damage site consisting of the oxidative base lesion, the reductive base lesion and the SSB (•OH action) would be formed within 10 bps DNA. Experimental evidences are scarce because of technical difficulties to detect base lesions proximately arising a SSB79. Recently, enhanced green fluorescent protein expressing plasmid DNA possessing SSBs were used to assess the SSB repair efficiency in human cells80. They showed that repair rate of the SSBs produced by X-rays were significantly lower than those produced by restriction enzymes, suggesting that the base lesions proximately positioned at the SSB termini compromise the access of DNA repair enzymes.

These results strongly indicate that the types and sites of clustered or complex DNA damage strongly depend on the amount of the initial deposition energy. As the energy deposited on DNA increases, DNA damage becomes more complex. On the other hand, as shown in Fig. 2b, ELF decreases with increasing energy, indicating that the higher energy deposition on DNA is reduced its frequency. Hence the damage complexity and its frequency have a compensatory relationship.

Even though these estimations were based on an assumption that e− aq and •OH induce damage with a same probability by their reactions with DNA, the results for SSBs, oxidative or reductive base damage are in excellent agreement with quantitative findings obtained in previous experiments where the yield of damage caused by an •OH, such as 8-oxo-G or SSB, was observed at approximately the same yields as reductive damage, such as dihydrothymine76. Furthermore, the results also showed that clusters containing the oxidative base damage are generated at approximately the same yield as clusters containing reductive base damage76, which successfully support our assumption that the e− aq and •OH arising proximately each other create a clustered DNA damage. Thus, the present study was the first to show that the nanoscale localization of radiation products of water decomposition causes clustering of DNA damage.

Future plan

We would be interesting to analyse experimental data for intermolecular Coulombic decay81 to advance electron ejection algorithm triggered by ionisation of valence band electron although the molecular conformational changes cannot be calculated. In addition to the dmcc_phys40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48 used in this study, the original chemical code (dynamic MCC for the chemical process; dmcc_chem) was developed82. dmcc_chem considers the dielectric response for calculating the diffusion and reaction of the chemical species generated in water. Recently, we calculated electronic states of poly (CG) DNA by first-principles calculation using OpenMX83. In the near future, dmcc_phys, dmcc_chem and OpenMX84 will be connected to demonstrate complexity of DNA damage formation.

Conclusion

The evaluation of spur-radius dependence on deposition energy by radiations or lasers is very important in radiation chemistry. This is because the reaction time of the produced chemical species strongly depends on the spur radius11,12,13,14,15,16. In other words, the reaction time strongly depends on the deposition energy. Whereas the previous studies47,48 focused on the formation of three-body chemical species, the present study focused on the 20–30 eV deposition energies that produce multi-body chemical species. When the energy deposited to water changes from 11 to 30 eV, the reaction time and reaction pathway of the chemical species also change. The present results provide new significant insights to the radiation chemistry.

The collision frequency distribution for water radiolysis was shown in our previous study46. However, the deposition energy dependence was not indicated. The present results for the dependence indicated that multiple collisions were induced when the deposition energy was around 22 eV and that multi-body spurs were formed when the energy exceeded 25 eV. Therefore, the energy deposition above 25 eV makes it possible to form the clustered DNA damage, which has important biological significance. These findings provide new significant insights into the radiation biophysics.

Yields for single-strand breaks and double-strand breaks of DNA have been measured by many experiments. Recently, although the yields of the clustered DNA damage have also been measured85, it is extremely difficult to detect redox lesions generated in the vicinity of the strand break. The yields of various types of the clustered DNA damage with the redox lesions could already be evaluated by computer simulations85. However, the simulation includes a bold model with simplified direct and indirect effects85. Currently, a reliable understanding of the formation mechanism of the clustered damage is desired over the model simulation. Our results provide a powerful clue to deeply understand the formation mechanism. Advanced quantitative evaluation of the damage yield will require a connection to the chemical code70. The connection will be realised in the near future.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Nikjoo, H. et al. Radiation track, DNA damage and response-a review. Rep. Prog Phys. 79, 116601 (2016).

Goodhead, D. T. Initial events in the cellular effects of ionizing radiations: clustered damage in DNA. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 65, 7–17 (1994).

Ward, J. F. DNA damage produced by ionizing radiation in mammalian cells: identities, mechanisms of formation, and reparability. Prog Nucl. Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 35, 95–125 (1988).

Alexey, I. F., Verkhovtsev, V. & Solov’yov, I. A. Solov’Yov, A. V. Lethal DNA damage caused by ion-induced shock waves in cells. Phys. Rev. E 104, 054408 (2021).

Surdutovich, E. & Solov’yov, A. V. Shock wave initiated by an ion passing through liquid water. Phys. Rev. E 82, 051915 (2010).

Bartels, D. M., Cook, A. R., Mudaliar, M. & Jonah, C. D. Spur decay of the Solvated Electron in Picosecond Radiolysis measured with time-correlated absorption spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. A 104, 1686–1691 (2000).

Muroya, Y. et al. A re-evaluation of the initial yield of the hydrated electron in the picosecond time range. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 72, 169–172 (2005).

Yang, J., Kondoh, T., Kan, K. & Yoshida, Y. Femtosecond pulse radiolysis and femtosecond electron diffraction. Nucl. Instr Meth A 629, 6–10 (2011).

Horne, G. P., Donoclift, T. A., Sims, H. E., Orr, R. M. & Pimblott, S. M. Multi-scale modeling of the Gamma Radiolysis of Nitrate Solutions. J. Phys. Chem. B 120, 11781–11789 (2016).

Ma, J., Wang, F., Denisov, S. A., Adhikary, A. & Mostafavi, M. Reactivity of prehydrated electrons toward nucleobases and nucleotides in aqueous solution. Sci. Adv. 3, e1701669 (2017).

Sander, M. U., Gudiksen, M. S., Luther, K. & Troe, J. Liquid water ionization: mechanistic implications of the H/D isotope effect in the geminate recombination of hydrated electrons. J. Chem. Phys. 258, 257 (2000).

Thomsen, C. L., Madsen, D., Keiding, S. R., Thogersen, J. & Christiansen, O. Two-photon dissociation and ionization of liquid water studied by femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 110, 3453 (1999).

Madsen, D., Thomsen, C. L., Thogersen, J. & Keiding, S. R. Temperature dependent relaxation and recombination dynamics of the hydrated electron. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 1126 (2000).

Kloepfer, J. A., Vilchiz, V. H., Lenchenkov, V. A., Germaine, A. C. & Bradforth, S. E. The ejection distribution of solvated electrons generated by the one-photon photodetachment of aqueous I – and two-photon ionization of the solvent. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 6288 (2000).

Crowell, R. A. & Bartels, D. M. Multiphoton Ionization of Liquid Water with 3.0 – 5.0 eV Photons. J. Phys. Chem. 100, 17940 (1996).

Elles, C. G., Jailaubekov, A. E., Crowell, R. A. & Bradforth, S. E. Excitation-energy dependence of the mechanism for two-photon ionization of liquid H2O and D2O from 8.3 to 12.4 eV. J. Chem. Phys. 125, 044515 (2006).

Elles, C. G., Shkrob, I. A., Crowell, R. A. & Bradforth, S. E. Excited state dynamics of liquid water: insight from the dissociation reaction following two-photon excitation. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 164503 (2007).

Savolainen, J., Uhlig, F., Ahmed, S., Hamm, P. & Jungwirth, P. Direct observation of the collapse of the delocalized excess electron in water. Nat. Chem. 6, 697–701 (2014).

Migus, A., Gauduel, Y., Martin, J. L. & Antonetti, A. Excess electrons in Liquid Water: first evidence of a Prehydrated State with Femtosecond Lifetime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 58, 1559–1562 (1987).

Gauduel, Y., Pommeret, S., Migus, A. & Antonetti, A. Femtosecond dynamics of geminate pair recombination in pure liquid water. J. Phys. Chem. 93, 3880–3882 (1989).

Silva, C., Walhout, P. K., Yokoyama, K. & Barbara, P. F. Femtosecond Solvation dynamics of the Hydrated Electron. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 1086–1089 (1998).

Assel, M., Laenen, R. & Laubereau, A. Dynamics of Excited Solvated electrons in Aqueous Solution monitored with femtosecond-time and polarization resolution. J. Phys. Chem. A 102, 2256–2262 (1998).

Thaller, A., Laenen, R. & Laubereau, A. Femtosecond spectroscopy of the hydrated electron: novel features in the infrared. Chem. Phys. Lett. 398, 459–465 (2004).

Kitajima, K., Tsuchida, H., Majima, T. & Saito, M. Secondary electron-induced biomolecular fragmentation in fast heavy-ion irradiation of microdroplets of glycine solution. J. Chem. Phys. 150, 095102 (2019).

Pimblott, S. M. & LaVerne, J. A. Stochastic Simulation of the Electron Radiolysis of Water and Aqueous solutions. J. Phys. Chem. A 101, 5828–5838 (1997).

Tomita, H., Kai, M., Kusama, T. & Ito, A. Monte Carlo simulation of physicochemical processes of liquid water radiolysis. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 36, 105–116 (1997).

Cobut, V. et al. Monte Carlo simulation of fast electron and proton tracks in liquid water—I. physical and physicochemical aspects. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 51, 229–243 (1998).

Nikjoo, H., Uehara, S., Emfietzoglou, D. & Cucinotta, F. A. Track-structure codes in radiation research. Radiat. Meas. 41, 1052–1074 (2006).

Uehara, S. & Nikjoo, H. Monte Carlo Simulation of Water Radiolysis for low-energy charged particles. J. Radiat. Res. 47, 69–81 (2006).

Plante, I. & Cucinotta, F. A. Cross sections for the interactions of 1 eV–100 MeV electrons in liquid water and application to Monte-Carlo simulation of HZE radiation tracks. New. J. Phys. 11, 063047 (2009).

Friedland, W., Dingfelder, M., Kundrát, P. & Jacob, P. Track structures, DNA targets and radiation effects in the biophysical Monte Carlo simulation code PARTRAC. Mutat. Res. 711, 28 (2011).

Incerti, S. et al. Track structure simulations of proximity functions in liquid water using the Geant4-DNA toolkit. J. Appl. Phys. 125, 104301 (2019).

Sato, T. et al. Features of particle and Heavy Ion Transport code system (PHITS) version 3.02. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 55, 684–690 (2018).

Matsuya, Y. et al. A simplified cluster analysis of Electron Track structure for estimating complex DNA damage yields. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 1701 (2020).

Kyriakou, I. et al. Review of the Geant4-DNA Simulation Toolkit for Radiobiological applications at the Cellular and DNA Level. Cancers 14, 35 (2022).

Shin, W. G. et al. Evaluation of the influence of physical and chemical parameters on water radiolysis simulations under MeV electron irradiation using Geant4-DNA. J. Appl. Phys. 126, 114301 (2019).

Incerti, S. et al. Geant4-DNA example applications for track structure simulations in liquid water: a report from the Geant4-DNA project. Med. Phys. 45, e722–e739 (2018).

Pimblott, S. M. & Mozumder, A. Structure of electron tracks in water. 2. Distribution of primary ionizations and excitations in water radiolysis. J. Phys. Chem. 95, 7291–7300 (1991).

Ritchie, R. H., Hamm, R. N., Turner, J. E. & Bolch, W. E. in Computational Approaches in Molecular Radiation Biology, Basic Life Sciences Vol. 63, edited by M. N. Varma and A. ChatterjeePlenum Press, New York, pp. 33–44. (1994).

Kai, T. et al. Dynamics of low-energy electrons in liquid water with consideration of Coulomb interaction with positively charged water molecules induced by electron collision. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 102, 16–22 (2014).

Kai, T., Yokoya, A., Ukai, M. & Watanabe, R. Cross sections, stopping powers, and energy loss rates for rotational and phonon excitation processes in liquid water by electron impact. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 108, 13–17 (2015).

Kai, T., Yokoya, A., Ukai, M., Fujii, K. & Watanabe, R. Thermal equilibrium and prehydration processes of electrons injected into liquid water calculated by dynamic Monte Carlo method. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 115, 1–5 (2015).

Kai, T., Yokoya, A., Ukai, M., Fujii, K. & Watanabe, R. Deceleration processes of secondary electrons produced by a high-energy Auger electron in a biological context. Int. J. Rad Bio 92, 654–659 (2016).

Kai, T., Yokoya, A., Ukai, M., Fujii, K. & Watanabe, R. Dynamic behavior of Secondary Electrons in Liquid Water at the Earliest Stage upon Irradiation: implications for DNA damage localization mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. A. 120, 8228–8233 (2016).

Kai, T. et al. A significant role of non-thermal equilibrated electrons in the formation of deleterious complex DNA damage. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 2838–2844 (2018).

Kai, T. et al. Initial yield of hydrated electron production from water radiolysis based on first-principles calculation. RSC adv. 13, 7076–7086 (2023).

Kai, T. et al. Nature of the physicochemical process in water photolysis uncovered by a computer simulation. J. Chem. Phys. 158, 164103 (2023).

Kai, T. et al. First-principles simulation of an ejected electron produced by monochromatic deposition energy to water at the femtosecond order. RSC Adv. 13, 32371–32380 (2023).

Lomax, M. E. & Gulston, M. K. O’Neill, P. Chemical aspects of clustered DNA damage induction by Ionising Radiation. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry 99, 63–68 (2002).

Shikazono, N., Noguchi, M., Fujii, K., Urushibara, A. & Yokoya, A. The yield, Processing, and Biological consequences of clustered DNA damage Induced by Ionizing Radiation. J. Radiat. Res. 50, 27–36 (2009).

Sage, E. & Harrison, L. Clustered DNA lesion repair in eukaryotes: relevance to mutagenesis and cell survival. Mutat. Res. 711, 123–133 (2011).

Prise, K. M., Pullar, C. H. & Michael, B. D. A study of endonuclease III-sensitive sites in irradiated DNA: detection of α-particle-induced oxidative damage. Carcinogenesis 20, 905–909 (1999).

Sutherland, B. M., Bennett, P. V., Sidorkina, O. & Laval, J. Clustered damages and total lesions induced in DNA by ionizing radiation: oxidized bases and strand breaks. Biochemistry 39, 8026–8031 (2000).

Ashley, J. C. & ENERGY LOSS RATE AND INELASTIC MEAN FREE PATH OF LOW-ENERGY ELECTRONS AND POSITRONS IN CONDENSED MATTER. J. Electr. Spectr. Rel Phen 50, 323–334 (1990).

Heller, J. M., Hammt, R. N., Birkhofft, R. D. & Painter, L. R. Collective oscillation in liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 60, 3483 (1974).

Paretzke, H. G., Goodhead, D. T., Kaplan, I. G. & Terrissol, M. Track structure quantities. In: Atomic and Molecular data for Radiotherapy and Radiation Research, Chap. 9. (IAEA-TECDOC-799) IAEA, Vienna (1995).

Faubel, M., Steiner, B. & Series, B. Photoelectron spectroscopy at liquid water surfaces, in Linking the Gaseous and Condensed Phases of Matter: The Behavior of Slow Electrons, NATO ASI Vol. 326, edited by Christophorou, L. G., Illenberger, E., and Schmidt W. FPlenum Press, New York,. pp. 517–523. (1994).

Hayashi, H. & Hiraoka, N. Accurate measurements of Dielectric and Optical Functions of Liquid Water and Liquid Benzene in the VUV Region (1 – 100 eV) using Small-Angle Inelastic X–ray scattering. J. Phys. Chem. B. 119, 5609–5623 (2015).

Itikawa, Y. & Mason, N. Cross Sections for Electron Collisions with Water molecules. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 34, 1–22 (2005).

Michaud, M., Wen, A. & Sanche, L. Cross sections for low-energy (1–100 eV) Electron Elastic and Inelastic Scattering in Amorphous Ice. Radiat. Res. 159, 3–22 (2003).

Yada, H., Nagai, M. & Tanaka, K. Origin of the fast relaxation component of water and heavy water revealed by terahertz time-domain attenuated total reflection spectroscopy. Chem. Phys. Lett. 464, 166–170 (2008).

Moliere, G. Theorie Der Streuung Schneller gelandener teilchen II: Mehrfachund Ielfachstreuung. Z. Naturforsch 3, 78–97 (1948).

Takayanagi, K. Introduction to electron-molecule collisions, in Electron-Molecule Collisions, edited by Shimamura, I. & Takayanagi, KPlenum Press, New York,. pp. 1–87. (1984).

KrajcarBronić, I., Kimura, M. & Inokuti, M. Time-dependent and temperature‐dependent aspects of electron distribution functions: H, Ar, and Cs atomic gases. J. Chem. Phys. 102, 6552–6558 (1995).

Matsuya, Y. et al. A step-by-step simulation code for estimating yields of water radiolysis species based on electron track-structure mode in the PHITS code. Phys. Med. Biol. 69, 035005 (2024).

Lacombe, L., Dinh, H. M., Reinhard, P., Suraud, P-G., Sanche, L. & E. & Rare reaction channels in real-time time-dependent density functional theory: the test case of electron attachment. Eur. Phys. J. D 69, 195 (2015).

Konovalov, V. V., Raitsimring, A. M. & Tsvetkov, Y. D. Thermalization lengths of subexcitation electrons in water determined by photoinjection from metals into electrolyte solutions. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 32, 623–632 (1988).

Nikjoo, H., O’Neill, P., Goodhead, D. T. & Terrissol, M. Computational modelling of low-energy electron-induced DNA damage by early physical and chemical events. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 71, 467–483 (1997).

Nikjoo, H., O’Neill, P. & Wilson, W. E. Goodhead. D. T. Computational approach for determining the spectrum of DNA damage induced by ionizing radiation. Radiat. Res. 156, 577–583 (2001).

Watanabe, R., Rahmanian, S. & Nikjoo, H. Spectrum of Radiation-Induced clustered Non-DSB damage - A Monte Carlo Track structure modeling and calculations. Radiat. Res. 183, 525–540 (2015).

Giese, B., Beyrich-Graf, X., Erdmann, P., Petretta, M. & Schwitter, U. The chemistry of single-stranded 4′-DNA radicals: influence of the radical precursor on anaerobic and aerobic strand cleavage. Chem. Biol. 2, 365–375 (1995).

Gugger, A., Batra, R., Rzadek, P., Rist, G. & Giese, B. Spectroscopic evidence for a Radical Cation as Intermediate in a Model reaction of the 4′-DNA radical strand cleavage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 8740–8741 (1997).

Yoshioka, Y. et al. Experimental and theoretical studies on the selectivity of GGG triplets toward one-Electron oxidation in B-Form DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 8712–8719 (1999).

O’Neill, P. & Fielden, E. M. Primary free radical processes in DNA. Adv. Radiat. Biol. 17, 53–120 (1993).

Yokoya, A., Cunniffe, S. M. T. & Peter, O. Effect of hydration on the induction of strand breaks and base lesions in plasmid DNA films by γ-Radiation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 8859–8866 (2002).

Shiina, T. et al. Induction of DNA damage, including abasic sites, in plasmid DNA by carbon ion and X-ray irradiation. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 52, 99–112 (2013).

Urushibara, A. et al. LET dependence of the yield of single-, double-strand breaks and base lesions in fully hydrated plasmid DNA films by 4He2+ ion irradiation. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 84, 23–33 (2008).

Ushigome, T. et al. Yield of single- and double-strand breaks and nucleobase lesions in fully hydrated plasmid DNA films irradiated with high-LET charged particles. Radiat. Res. 177, 614–627 (2012).

Yokoya, A., Cunniffe, S. M. T., Stevens, D. L. & O’Neill, P. Effects of Hydration on the induction of strand breaks, base lesions, and clustered damage in DNA films by α-Radiation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 107, 832–837 (2003).

Obata, Y., Nakaue, H., Hirasaki, K., Akimitsu, N. & Yokoya, A. Expression of an X-Ray irradiated EGFP-Expressing plasmid transfected into Nonirradiated Human cells. Radiat. Res. 196, 261–271 (2021).

Mucke, M. et al. Hergenhahn, U. A hitherto unrecognized source of low-energy electrons in water. Nat. Phys. 6, 143–146 (2010).

Toigawa, T., Kai, T., Kumagai, Y. & Yokoya, A. Consideration of the Dielectric response for Radiation Chemistry simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 160, 214119 (2024).

Sekikawa, T. et al. Kai. T. Changes in molecular conformation and electronic structure of DNA under 12C ions based on first-principles calculations. NIMB 548, 165231 (2024).

Open source package for Material eXplorer. http://www.openmx-square.org.

Yachi, Y. et al. An Analytical Method for quantifying the yields of DNA double-strand breaks coupled with strand breaks by γ-H2AX focus formation assay based on track-structure Simulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 1386 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr T. Sekikawa (JAEA) for useful discussions on TDDFT.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (Grant no. 22K04993, 22K14631, 22H03744, 22K14630 and 22K03549).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T. K and T. T designed this work. T. K developed the dynamic Monte Carlo code for the physical process and performed all calculations. Y. M and Y. H contributed to the discussion on developing the code and radiation physics. H. T and T. T contributed to the discussion of radiation physics. T. T contributed to the discussion of radiation chemistry. A. Y supervised this study. T. K wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion of this study and have reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kai, T., Toigawa, T., Matsuya, Y. et al. Significant role of secondary electrons in the formation of a multi-body chemical species spur produced by water radiolysis. Sci Rep 14, 24722 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76481-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76481-z