Abstract

Recently, a founder Alu insertion in exon 4 of RP1 was detected in Japanese and Korean patients with inherited retinal diseases (IRDs). However, carrier frequency and diagnostic challenges for detecting AluY insertion are not established. We aim to investigate the frequency of AluY in individuals with or without IRDs and to overcome common diagnostic pitfalls associated with AluY insertion. A total of 1,072 subjects comprising 411 patients with IRD (IRD group) and 661 patients with other suspected Mendelian genetic disease (non-IRD group) was screened for AluY insertion. Targeted panel sequencing and whole-genome sequencing were used for detection of AluY insertion, and an optimized allele-specific PCR (AS-PCR) was used for validation. The AluY insertion was detected in 1.5% in IRD group (6/411). The AluY insertion was not observed in non-IRD group (0/661). All patients with AluY were confirmed to have RP1 pathogenic variants on the paired allele. We identified AluY allele dropout leading to false homozygosity for c.4196del pathogenic variant in Sanger sequencing. The allelic relationship between variants of RP1 was accurately determined by AluY AS-PCR. Delineating diagnostic challenges of AluY insertion and strategies to avoid potential pitfalls could aid clinicians in an accurate molecular diagnosis for patients with IRD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inherited retinal diseases (IRDs) are a group of diverse genetic disorders associated with visual impairment due to progressive degeneration of the retina and affect more than 2 million people worldwide1,2. Genetic diagnosis of IRDs is particularly challenging and often delayed due to the extensive genetic heterogeneity and overlapping, variable, and incompletely penetrant nature of the clinical presentation1,2. To date, more than 280 genes have been identified as responsible for IRD development, with either autosomal dominant or recessive or X-linked inheritance patterns (RetNet, https://sph.uth.edu/retnet/ last accessed on February 2024). Retinitis pigmentosa (RP, MIM #268000) is the most common IRD, primarily affecting the rod and cone photoreceptors and is characterized by night blindness, progressive visual field loss, and eventual loss of visual acuity3,4. The molecular etiology of RP is complicated5,6, and mutations in at least 80 genes have been postulated as responsible for causing RP (RetNet).

The RP1gene is associated with RP and encodes a microtubule-associated protein localized to connecting cilia of rod and cone photoreceptors. This protein is required for stability and organization of the disc membranes in the outer segment7,8,9. RP1has been implicated in both autosomal dominant RP (adRP) and autosomal recessive RP (arRP), accounting for approximately 5.5% and 1% of cases, respectively10. More than 280 disease-causing mutations of RP1 listed in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD, professional version 2023.4), and most are truncating variants.

Recently, an insertion of the mobile element Alu in exon 4 of RP1was reported as a founder mutation in Japanese subjects with IRD11,12,13. The AluY insertion resulted in 328 additional nucleotides in exon 4 of RP1 and a premature termination codon in the canonical RP1coding sequence, c.4052_4053ins328, p.(Tyr1352AlafsTer9)12. In a recent study, the prevalence of the AluY insertion was 1.8% in 273 Korean patients with an IRD based on targeted panel sequencing or whole-exome sequencing14. However, the number of IRD patients included in that study was limited14, and knowledge regarding the carrier frequency of the AluY insertion in the population without retinal phenotype is limited. In addition, AluY is an insertion of more than 300 nucleotides, which may complicate detection or validation when using routine PCR-based sequencing methods; however, the potential diagnostic pitfalls for use in clinical molecular laboratory have not yet been addressed.

In this study, we analyzed targeted or whole genome sequencing data of 1,072 individuals of Korean descent to investigate the prevalence of the AluY insertion in the largest study reported to date. We also present various diagnostic pitfalls associated with molecular diagnosis of AluY insertion and suggest efficient and accurate diagnostic strategies.

Results

Population frequency of the AluY insertion in RP1

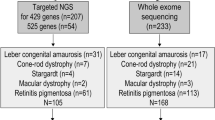

Among the 1,072 samples, the AluY insertion was detected as heterozygous in six patients, all of which were found in the IRD group with genotype frequency of 0.0146 (6/411; 95% CI, 0.0067–0.0315) and allele frequency of 0.0073 (6/822; 95% CI, 0.0033–0.0158). An AluY insertion was not observed in non-IRD group (0/661) (Fig. 1).

RP1 variant spectrum accompanying the AluY insertion

The AluY insertion in RP1 was found in six patients in the IRD group, five with RP and one with cone dystrophy. All patients were confirmed to have pathogenic variant in trans with the AluY insertion as follows: c.2398 A > G: p.(Lys800Ter) (N = 1), c.4196del: p.(Cys1399LeufsTer5) (N = 2), c.5797 C > T: p.(Arg1933Ter) (N = 1), and c.6181del: p.(Ile2061SerfsTer12) (N = 2). The clinical characteristics and genetic data for these AluY insertion cases are summarized in Table 1.

Diagnostic pitfalls associated with AluY insertion in RP1

AluY allele dropout leading to false homozygosity for RP1 c.4196del variant

In two unrelated RP patients (study IDs: 41 and 89), the pathogenic variant c.4196del was detected along with the AluY insertion using targeted panel sequencing. In the subsequent Sanger validation, allele dropout (ADO) was suspected due to c.4196del variant homozygosity (Fig. 2A). We performed repeated sequencing using redesigned primers for exon 4 to avoid the AluY insertion as shown in Fig. 2B and confirmed that dropout of the AluY allele causes a false-negative result, and dropout of the wild-type allele caused a heterozygous c.4196del variant to appear homozygous (Fig. 2B; Supplementary Table S1). The ADO was presumed to be caused by expansion of the allele size due to an AluY insertion in the sample DNA, resulting in non-amplification of one of the two alleles.

Error in detection of the c.4196del variant in RP1 due to AluY allele dropout (ADO) in two families with retinitis pigmentosa. (a) Homozygous deletion of the RP1 c.4196del variant in two unrelated RP patients. (b) Resequencing with redesigned primers (P2-F and P2-R) avoiding the AluY insertion detected heterozygous deletion of the RP1 c.4196del variant in the two patients.

Allele phasing to discriminate mutant alleles for AluY and c.4196del

Phase information is important for diagnosis of arRP caused by compound heterozygous mutations. To resolve cis or trans ambiguities between mutated alleles for AluY and c.4196del genetic backgrounds, we designed one set of specific amplification reaction based on the specific primers and AS-PCR protocols (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Table S2). The specificity of the AS-PCR reaction involved a single 3’ mismatched nucleotide for c.4196del, which was sufficient to prevent extension. DNA fragments containing the AluY insertion were distinguished from DNA fragments not containing the AluY insertion based on size (approximately 600 bp vs. 300 bp) and existed in trans with c.4196del (Fig. 3B).

Discrimination of mutant alleles for AluY and c.4196del in RP1. (a) Schematic diagram of allele-specific PCR design and expected product size depending on cis or trans status of AluY and c.4196del. (b) A DNA fragment containing the AluY insertion was distinguished from a fragment not containing the AluY insertion by size (approximately 600 bp vs. 300 bp) and was positioned in trans with c.4196del. The samples were derived from the same experiment and gels were processed in parallel. The original gel image is in Supplementary Figure S1.

Revealing the allelic status of c.4196del and c.6353G > A variants using long-read allele phasing

The c.6353G > A: p.(Ser2118Asn), listed as a disease-causing mutation for RP in HGMD, was heterozygous in two unrelated RP patients in this study, all of whom harbored the c.4196del variant. To obtain phasing information of each allele, we performed long-read sequencing on the MinION platform by Oxford Nanopore Technologies. In the obtained MinION sequences, c.6353G > A and c.4196del variants were on the same allele (Fig. 4).

Phasing of the allelic relationships between c.4196del and c.6353G > A variants in RP1 using long-read sequencing. In long-read allele phasing, c.4196del and c.6353G > A variants are on the same allele and are trans with AluY insertion. The dotted boxes show the allelic relationships of AluY (red box) with c.4196del and c.6353G > A (blue boxes) of RP1. The position of each variant is indicated by an arrowhead.

Diagnostic strategy for AluY insertion inRP1 using integrated approach

To efficiently and accurately detect the AluY insertion, we proposed an integrated approach that can be used in a diagnostic laboratory. In our laboratory, we routinely perform in silico screening using the Grep search program, developed by Won et al14., on all samples requested for targeted panel sequencing for RP and related eye disorders. When the Grep program returns a result of “AluY insertion suspected” or pathogenic variant in RP1 is found to be heterozygous in patient from targeted panel sequencing, we directly visually inspect the sequence using IGV. For subsequent validation, AS-PCR and gel electrophoresis are performed for the suspected AluY insertion. We designed AS-PCR primers to detect chimeric sequences containing RP1 and AluY sequences surrounding target site duplication, which allowed accurate identification of the AluY insertion (Fig. 5).

Confirmation of the AluY insertion by allele-specific PCR and gel electrophoresis. DNA fragments approximately 240 bp in size containing a chimeric sequence of RP1 and AluY were detected in patients with retinitis pigmentosa but not in control. These samples were derived from the same experiment and gels were processed in parallel.

Discussion

In the current study, 1.5% (6/411) of the Korean patients examined had the AluY insertion in RP1. All of these insertions were heterozygous and only detected in the IRD group. A previous study has reported the absence of AluY insertion in publicly available resources such as the 1,000 Genomes Project and gnomAD SV2.114. In the gnomAD SV4.1.0 database, AluY insertion was found in only one of 4,044 individuals of East Asian ancestry (structural variant ID: INS_CHR_E1ED31D9). In the Korean Variant Archive II (KOVA II, www.kobic.re.kr/kova/, last accessed July 2024), no AluY insertion was detected among 1,896 whole genome sequencing samples. These findings suggest that the AluY insertion in RP1 is very rare in control populations, aligning with our study results. However, it should be noted that different bioinformatic tools were used for analyzing the KOVA II and the gnomAD SV4.1.0 data, which may lead to difference in the ability to detect AluY insertion. A strength of this study compared to previous study is that we directly analyzed the frequency of AluY insertion in RP1 using high-quality, genome-scale raw sequencing data in Korean population with or without retinal disease phenotypes. This work provided several important findings. First, the prevalence of AluY insertion in this Korean study population was within the range of previously published results. In a prior study including 331 Japanese patients with hereditary retinal degenerations, the AluY insertion was detected in 1.8% (12/662 alleles) of patients and was a prevalent cause of the disease12. In another study by Won et al.14, among 273 patients with retinal phenotypes such as Leber congenital amaurosis, cone-rod dystrophy, macular dystrophy, and RP, the authors found an AluY insertion frequency of 1.8% (5/273). The AluY insertion is the founder mutation of arRP, with a high allele frequency in Japan ranging from 9.8% to 32%11,15. The arRP is more common than the adRP in the Asian population16,17,18,19. The high frequency indicate that accurate detection of the AluY insertion in IRD patients with genetic heterogeneity, especially arRP patients, may be an important factor in increasing the diagnostic yield.

Second, we determined the spectrum of variants detected with the AluY insertion in RP1 and revealed common diagnostic issues encountered when detecting mutations in the laboratory due to the AluY insertion. Among the identified variants, c.4196del was found in two patients with compound heterozygous RP in the AluY insertion. This variant is present at a rate of 0.005% in a population database (gnomAD v2.1.1) and creates a premature stop signal p.(Cys1399LeufsTer5) in the RP1 protein. However, this mutation is not anticipated to result in nonsense-mediated mRNA decay because it occurs in the last exon of RP120and is expected to disrupt the last 758 amino acids of the RP1 protein. The c.4196del variant has been observed in individuals with clinical features of arRP12,21,22. In our study, we confirmed that when this variant is accompanied by an AluY insertion, ADO occurs depending on the binding position of the primer, leading to incorrect detection of the variant’s allelic status. Therefore, it is important to design and validate primers that avoid the AluY insertion when testing for the RP1 c.4196del variant in the laboratory.

Notably, the c.6353G > A: p.(Ser2118Asn) variant is on the same allele as the c.4196del: p.(Cys1399LeufsTer5) variant in RP1. The c.6353G > A is listed as a disease-causing mutation for RP in HGMD. This mutation has been reported in many patients with IRDs; in previously reported cases, the c.6353G > A variant was found together with the c.4196del variant19,21,22,23. Some cases were confirmed cis relationships of the variants based on parental testing21,23. If the allelic status is not verified, the simultaneous identification of c.6353G > A and c.4196del variants may lead to misdiagnosis as an autosomal recessive disease. In the current study, we confirmed that the allelic status of both RP1variants were confirmed to be cis using long-read sequencing. Short reads of only a few hundred bases at the longest lack the phasing information of each allele. Therefore, in this study, we verified the phases of the two variants, c.6353G > A and c.4196del, using long-read sequencing, which is suitable for revealing mutation status at the allele level24.

The c.5797 C > T variant creates a premature stop signal p.(Arg1933Ter). This variant is in the C-terminus of the RP1 and is predicted to result in protein truncation because the last 224 amino acids are lost. Many other loss-of-function variants that disrupt this region have been reported in patients with either autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive RP25,26,27,28,29. Therefore the c.5797 C > T variant is also expected to be pathogenic and considered mainly associated with autosomal recessive inheritance27,30,31. In a prior study, the c.5797 C > T variant was observed at a high frequency of 0.6% in 12,000 individuals without retinal degeneration but was significantly enriched (3.5-fold) in patients with IRDs12. The authors concluded that c.5797 C > T can act as a pathogenic variant in trans with AluY insertion based on familial co-segregation and association analyses12. In the current study, the c.5797 C > T variant was found in one male patient with cone dystrophy. Through past genetic testing, heterozygosity for c.5797 C > T in RP1 was confirmed in the patient, but no other mutations were found, preventing a final genetic diagnosis. The patient was later diagnosed with autosomal recessive disease following identification of the AluY insertion. The c.5797 C > T variant and AluY insertion were inherited from his mother and father, respectively.

RP is a very complex disease due to genetic and clinical heterogeneity6. Clinical diagnosis of RP often relies on electroretinography and visual field testing results. However, its similarity to progressive pigmentary degeneration of the fundus can complicate diagnosis21. Thus, identification of disease-causing mutations in affected individuals is essential for genetic counseling, carrier testing, and gene-specific therapies. In this study, we demonstrated that AluY insertion in RP1 is common in the Korean population with IRDs and occurs in conjunction with other pathogenic variants in a compound heterozygous state. Our study also indicated the need for understanding the diagnostic pitfalls of AluY insertion in RP1 and for establishing diagnostic strategies, such as AluY-specific AS-PCR, to overcome them.

Methods

Study population

Sequencing data of 1,072 individuals of Korean descent, from 411 patients with IRD (IRD group) and from 661 patients with underlying genetic diseases other than eye diseases (non-IRD group) were screened for the AluY insertion in exon 4 of RP1 (Fig. 1). The sequence data for the IRD group were obtained from targeted panel sequencing, selectively capturing genes associated with RP and related eye disorders, conducted from May 2019 to December 2023. We also investigated non-IRD group sequence data from 661 consecutive, unrelated Korean patients with suspected Mendelian disorders who underwent whole-genome sequencing (WGS) between 2021 and 2022 for the National Project of Bio Big Data. The underlying disease conditions for patients in the non-IRD group were summarized in Supplementary Table S3. The genetic study with WGS (IRB No.: SMC 2020-10-042) and retrospective data analysis (IRB No.: SMC 2024-03-059) were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent for genetic testing and research use of biological and related clinical data was obtained from all investigated subjects. No images or video or details that could identify the subjects were used in the study.

Targeted panel sequencing

DNA underwent sequencing with a targeted panel designed to selectively capture 199 genes associated with RP and related eye disorders (Supplementary Table S4). Targeted DNA fragments were sequenced on a NextSeq550 or NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Sequence reads were aligned against human reference genome GRCh19 (hg19) using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA v0.7.17) and then sorted the output and removed PCR duplicates using Picard v2.19.0. Using GATK workflow (v4.1.2), we processed the data for local indel realignment and base quality recalibration. Variant calling was performed using Strelka2 (v2.9.10), VarDict, and Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK, v4.1.2), and variants were annotated using SnpEff (v4.3). Data analysis was performed on variants located within ± 25 base pairs (bp) of the coding exon, considering population frequency, effect on the encoded protein, and conservation and expression of the variant. The 2015 American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics/Association for Molecular Pathology variant interpretation guidelines were used to determine the pathogenicity of variants20.

Whole-genome sequencing

Genomic DNA from peripheral blood was collected for WGS. After DNA fragmentation, preparation of the library was performed without amplification. The library was paired-end sequenced using a NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina) at a mean depth of 35×. The sequence reads were aligned to human reference genome GRCh38 (hg38) using Burrows-Wheeler Alignment Aligner (v0.7.17). Subsequent preprocessing and variant calling were performed using GATK (v4.2.0). Variant annotation was performed using ANNOVAR and SnpEff for all genome sequences including introns.

Identification of AluY insertion in RP1

We screened sequencing data of 1,072 individuals of Korean descent from the IRD and non-IRD groups using the Grep search program to detect the AluY insertion in exon 4 of RP1. The Grep program is an in silico method for detecting AluY insertion in RP1from FASTQ files through next-generation sequencing, based on the known sequence of the mutant junction14. The Linux Grep command was used to search FASTQ files for the chimeric sequence of the 5’ junction between the reference sequence of exon 4 and the beginning of the AluY insertion in RP114. The chimeric sequences were forward, 5’-CCAAAGAAAACACggccgggcgcggt-3’; reverse, 5’-accgcgcccggccGTGTTTTCTTTGG-3’ (lowercase bases are the AluY sequence). When AluY insertion was suspected in the screening results of the Grep search, soft-clipped sequences from the BAM file were visually inspected using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) to determine if the observed sequence was identical to that of the known AluY retrotransposon junction.

AluY allele-specific PCR and gel electrophoresis

We performed AluY allele-specific PCR (AS-PCR) and gel electrophoresis to confirm the suspected AluY insertion in RP1 from the Grep search and IGV visual inspection. To target the AluY allele-specific sequence, we designed primers to amplify 239 bp, including 145 bp upstream and 83 bp downstream of target site duplication (sequence: 5’-AAAGAAAACAC-3’; Supplementary Table S5). Experimental condition for AS-PCR is described in detail in the Supplementary methods. The AluY insertion between c.4052 and c.4053 in exon 4 of RP1 was confirmed when a 328-bp insertion was identified on agarose gel electrophoresis of the tested sample. For the subsequent Sanger validation, PCR products were sequenced on an ABI 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using a BigDye Terminator Cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems). Sequences were analyzed using Sequencher software (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and were compared with the reference sequences for RP1 (NM_006269.1) and AluY (GenBank accession number JN391998.1). Gel images adhered to digital image and integrity policies and were obtained from samples processed in parellel from the same experiment.

Long-read sequencing

For phase determination, long-read sequencing was performed by MinION flowcell (version 9.4.1) (Oxford Nanopore Technology). For cost-effectiveness of sequencing, last exon of RP1 in which Alu inserted was enriched by CRISPR-Cas9 system. CRISPR RNA (crRNA) was designed spanning 7,506 bp region by CHOPCHOP (https://chopchop.cbu.uib.no/) as follows; crRNA: 5’-ACCGCAATCTCAAGCAGAAG-3’ and 5’-GGTACTGTTACCCATCGAGA-3’. Experiments were done according to the protocol (version ENR_9084_v109_revD_04Dec2018). Base calling and alignment were conducted by MinKNOW (v20.06.5) and sequences were visualized by IGV.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this manuscript are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Berger, W., Kloeckener-Gruissem, B. & Neidhardt, J. The molecular basis of human retinal and vitreoretinal diseases. Prog Retin Eye Res. 29, 335–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2010.03.004 (2010).

Ellingford, J. M. et al. Whole genome sequencing increases Molecular Diagnostic Yield compared with current diagnostic testing for inherited retinal disease. Ophthalmology. 123, 1143–1150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.009 (2016).

Wang, A. L., Knight, D. K., Vu, T. T. & Mehta, M. C. Retinitis Pigmentosa: review of current treatment. Int. Ophthalmol. Clin. 59, 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1097/iio.0000000000000256 (2019).

Verbakel, S. K. et al. Non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa. Prog Retin Eye Res. 66, 157–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2018.03.005 (2018).

Nguyen, X. T. et al. Retinitis Pigmentosa: current clinical management and emerging therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24087481 (2023).

Sorrentino, F. S., Gallenga, C. E., Bonifazzi, C. & Perri, P. A challenge to the striking genotypic heterogeneity of retinitis pigmentosa: a better understanding of the pathophysiology using the newest genetic strategies. Eye (Lond). 30, 1542–1548. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.197 (2016).

Liu, Q., Zuo, J. & Pierce, E. A. The retinitis pigmentosa 1 protein is a photoreceptor microtubule-associated protein. J. Neurosci. 24, 6427–6436. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.1335-04.2004 (2004).

Liu, Q. et al. Identification and subcellular localization of the RP1 protein in human and mouse photoreceptors. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43, 22–32 (2002).

Liu, Q., Lyubarsky, A., Skalet, J. H., Pugh, E. N. Jr. & Pierce, E. A. RP1 is required for the correct stacking of outer segment discs. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44, 4171–4183. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.03-0410 (2003).

Hartong, D. T., Berson, E. L. & Dryja, T. P. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet. 368, 1795–1809. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(06)69740-7 (2006).

Nishiguchi, K. M. et al. A founder Alu insertion in RP1 gene in Japanese patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Jpn J. Ophthalmol. 64, 346–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10384-020-00732-5 (2020).

Nikopoulos, K. et al. A frequent variant in the Japanese population determines quasi-mendelian inheritance of rare retinal ciliopathy. Nat. Commun. 10, 2884. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10746-4 (2019).

Verbakel, S. K. et al. Macular Dystrophy and cone-rod dystrophy caused by mutations in the RP1 gene: extending the RP1 Disease Spectrum. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 60, 1192–1203. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.18-26084 (2019).

Won, D. et al. In Silico identification of a common mobile element insertion in exon 4 of RP1. Sci. Rep. 11, 13381. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92834-4 (2021).

Mizobuchi, K. et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations in RP1-Associated Retinal dystrophies: a Multi-center Cohort Study in JAPAN. J. Clin. Med. 10https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10112265 (2021).

Kim, Y. J. et al. Diverse Genetic Landscape of Suspected Retinitis Pigmentosa in a Large Korean Cohort. Genes (Basel) 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12050675 (2021).

Kim, Y. N. et al. Genetic profile and associated characteristics of 150 Korean patients with retinitis pigmentosa. J. Ophthalmol. 5067271. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5067271 (2021).

Ma, D. J. et al. Whole-exome sequencing in 168 Korean patients with inherited retinal degeneration. BMC Med. Genom. 14, 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-021-00874-6 (2021).

Koyanagi, Y. et al. Genetic characteristics of retinitis pigmentosa in 1204 Japanese patients. J. Med. Genet. 56, 662–670. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2018-105691 (2019).

Richards, S. et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 17, 405–424. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2015.30 (2015).

Wang, J. et al. Dependable and efficient clinical utility of target capture-based deep sequencing in molecular diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 55, 6213–6223. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.14-14936 (2014).

Huang, H. et al. Systematic evaluation of a targeted gene capture sequencing panel for molecular diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa. PLoS One. 13, e0185237. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185237 (2018).

Sun, Y. et al. Genetic and clinical findings of panel-based targeted exome sequencing in a northeast Chinese cohort with retinitis pigmentosa. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 8, e1184. https://doi.org/10.1002/mgg3.1184 (2020).

Conlin, L. K., Aref-Eshghi, E., McEldrew, D. A., Luo, M. & Rajagopalan, R. Long-read sequencing for molecular diagnostics in constitutional genetic disorders. Hum. Mutat. 43, 1531–1544. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.24465 (2022).

Berson, E. L. et al. Clinical features and mutations in patients with dominant retinitis pigmentosa-1 (RP1). Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 42, 2217–2224 (2001).

Chen, L. J. et al. Compound heterozygosity of two novel truncation mutations in RP1 causing autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51, 2236–2242. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.09-4437 (2010).

Li, S. et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing reveals novel RP1 mutations in autosomal recessive Retinitis Pigmentosa. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomarkers. 22, 109–114. https://doi.org/10.1089/gtmb.2017.0223 (2018).

Kurata, K., Hosono, K. & Hotta, Y. Clinical and genetic findings of a Japanese patient with RP1-related autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Doc. Ophthalmol. 137, 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10633-018-9649-7 (2018).

Wang, J. et al. Dominant RP in the Middle while recessive in both the N- and C-Terminals due to RP1 truncations: confirmation, refinement, and questions. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 634478. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.634478 (2021).

Fujinami, K. et al. Novel RP1L1 variants and genotype-photoreceptor Microstructural phenotype associations in Cohort of Japanese patients with Occult Macular dystrophy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 57, 4837–4846. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.16-19670 (2016).

Maeda, A. et al. Development of a molecular diagnostic test for Retinitis Pigmentosa in the Japanese population. Jpn J. Ophthalmol. 62, 451–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10384-018-0601-x (2018).

Funding

This study was supported by a grant (No. 2021R1F1A1046537) of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korea government (MSIT) and a grant (No. SMO1220671) from Samsung Medical Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J-HJ planned the study. M-AJ and JKL performed data curation and investigation. M-AJ performed the data analysis, data visualization, and writing-original draft. J-HP, Y-JH, SH, Y-GK, and J-WK involved in sample collection and investigation. SJK and J-HJ performed supervision, writing-review and editing. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jang, MA., Lee, J.K., Park, JH. et al. Identification of diagnostic challenges in RP1 Alu insertion and strategies for overcoming them. Sci Rep 14, 25119 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76509-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76509-4