Abstract

This study explores the relationship between surface roughness and characteristic scale through theoretical analyses and experimental data. Considering the concavity and convexity of cycloidal gear tooth profile curvatures, a curved surface contact coefficient model suitable for both inner and outer contacts, with either equal or unequal curvatures, has been developed. Moreover, a fractal contact model is constructed for cycloidal pinwheels. This model considers scale correlation and analyzes the influence of microscopic parameters on the elastic-plastic critical grade and the behavior of the contact area. Additionally, the influence of the micro-convex body frequency index on surface contact performance is explored to provide theoretical insights for improving the elastic contact ratio and reducing wear on contact surfaces.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Studies show that sliding friction between rough surfaces primarily occurs at micro-convex body, resulting in an actual contact area that is only a small fraction of the nominal or apparent area. Understanding the real contact characteristics of cycloidal pin gears, particularly concerning surface roughness, is essential for enhancing the performance of core robotic components. This study is crucial for examining their friction, wear, lubrication, and heat transfer performance.

Reviewing the literature demonstrates that numerous investigations have been carried out focusing on friction sliding. For instance, Xu1,2developed a dynamic model for the RV reducer that includes the effects of the crankshaft bearing, accurately predicting the engagement count of pin teeth with the cycloidal pinwheel while considering assembly clearance. Li3created a load-bearing contact analysis model for cycloidal gears, predicting the loads on each component under conditions of clearance and eccentricity errors. Zhang et al4. investigated the impact of progressive wear over time on the key performance aspects of the RV reducer, such as transmission effectiveness, accuracy in terms of transmission error, and torsional stiffness. Wang5determined the maximum meshing stiffness through optimization under the optimal modification. Yang et al6. used finite element software to analyze the torsional stiffness of cycloidal wheels, considering the effects of dynamic parameters, the number of engaging teeth, and material properties on torsional stiffness from a macroscopic perspective. Although remarkable achievements have been obtained, these models did not consider the influence of the micro-morphology of the gear surface when analyzing the load-bearing meshing characteristics of the cycloidal gear.

Majumdar and Bhushan7,8,9,10 introduced an M-B contact model based on fractal geometry, which primarily analyzes contact between two rough planar surfaces without accounting for friction. This model, however, does not address contact issues between two rough curved surfaces.

Based on the M-B model, Wang et al11,12. developed a fractal contact model for rough surfaces that includes various deformation states of micro-convex body, including elastic, elastoplastic, and plastic, as well as the influence of friction at the contact interface. Ding13developed a fractal contact model for rough surfaces from a microscopic perspective, focusing on the length of the substrate. Wei et al14. proposed a sliding friction surface contact mechanics model based on fractal theory, which considers the characteristics of micro-convex body and the effect of friction. Yuan et al15,16. established a scale-related fractal rough surface elastoplastic contact mechanics model that takes the level of micro-convex body into account, analyzing the normal contact stiffness of the joint surface. Yu et al17. extended the principle of continuous length scales in micro-convex body features to create a normal contact stiffness model for curved surfaces, incorporating the influence of the friction factor.

Zhao et al18,19. developed a fractal contact model for two cylindrical bodies, creating a curved surface contact coefficient to represent the contact between two curved surfaces. They also analyzed surface contact and calculated the contact stiffness of the joint surface between the cylinders. Chen et al20. designed a spherical contact model that includes the friction factor to accurately compute the normal contact stiffness. Ma et al21. established a fractal contact model for the sliding friction of arc gears. Han et al22,23. devised a curved surface contact coefficient that incorporates the micro-features of the contact tooth surface, establishing a fractal contact model for cycloidal gear teeth and pin teeth, and analyzed the impact of both macroscopic and microscopic parameters on the contact characteristics. Yang et al24. proposed a micro-morphology model of the cycloidal gear with parabolic modification, calculating the normal contact stiffness of the cycloidal gear meshing surface under elastic deformation.

This study incorporates theoretical predictions and experimental validations to determine the quantitative relationship among surface roughness, fractal dimension, and characteristic scale. Given the unique concave-convex curve of the cycloidal gear tooth profile, a curved surface contact coefficient is established to address internal and external contacts with identical and varying curvatures. Considering the hierarchy of micro-convex body, this paper develops a fractal contact model for micro-convex body and analyzes the influence of macroscopic and microscopic parameters on contact characteristics.

Determination of fractal dimension D and characteristic scale G

The rough surface obtained through experimental methods is accurate; however, the sampling results depend heavily on the precision of the equipment. Furthermore, a large sample size requires an extended preparation period. A mathematical model can effectively capture the morphological characteristics of actual machined surfaces and offers a high degree of model convergence. Accordingly, developing an accurate model is an appropriate scheme to analyze the contact and wear characteristics of joint surfaces.

Majumdar and Bushan10 employed the Weierstrass-Mandelbrot (WM) function to establish one of the first fractal contact models, hereinafter referred to as the MB model. In the MB model, the rough surface texture is based on a 2D multiscale surface profile z(x) generated by the WM function, in which the surface roughness is given by

Where x is the contour displacement coordinate, \({\gamma ^n}\) is the frequency spectrum of the rough surface (\(\gamma >1\)), \(\gamma\) is generally taken as 1.5, D represents the fractal dimension, G is the characteristic scale, and n is the frequency index, reflecting the level of micro-convex body.

The influence of D and G on the distribution of micro-convex body

Equation (1) indicates that the distribution of z(x) is primarily influenced by the parameters D, G, and n, where n is mainly determined by the sampling length and the resolution of the instrument.

Figure 1 reveals that the value of the parameter D exhibits a positive correlation with the complexity of the curve. A larger D value signifies a more intricate profile structure and a richer level of detail. Meanwhile, as the fractal dimension D increases, the amplitude of the curve decreases.

Figure 2 shows that as the characteristic scale G increases, the amplitude of the distribution curve significantly increases. It is worth noting that the characteristic scale of the machined surface determines the amplitude of the surface roughness, which directly affects the contact performance of the contacting surfaces.

Determination of D and G suing the structural function method

Fractal dimension and characteristic scale are critical parameters for characterizing the fractal features of surface morphology. Due to its low computational error, this paper employs the structural function method to determine the fractal dimension D and characteristic scale G.

The structural function method9 considers a surface roughness profile as a time series \({z_i}(x)\), and a time series with fractal characteristics ensures that its sampled data satisfies the following expression:

Where \({\left[ {{z_i}\left( {x+\tau } \right) - {z_i}\left( x \right)} \right]^2}\) represents the arithmetic mean of the differences, and \(\tau\) is an arbitrarily chosen value for the data interval. For various scales \(\tau\), the corresponding \(S(\tau )\) values of the contour curve’s discrete signal are calculated. Subsequently, a double logarithmic coordinate graph of Eq. (2) is constructed. In the double logarithmic coordinate graph, the slope \(\alpha\) of the straight line corresponding to \(\lg \left( {S(\tau )} \right) - \lg \tau\) is obtained. Subsequently, the fractal dimension D can be obtained using the following expression:

It is inferred that the intercept \(\lg c\)and the characteristic scale G in the logarithmic coordinate diagram satisfy the following relationship:

Cycloidal gears are typically produced through grinding. The fractal dimension D of the machined surface does not exhibit a linear correlation with roughness; instead, the fractal dimension increases as the surface roughness decreases. The characteristic scale G significantly affects the amplitude of the fractal roughness simulation. Therefore, accurately determining both the fractal dimension D and the characteristic scale G is crucial for performing a detailed fractal simulation and contact analysis of the cycloidal gear tooth surface.

Chen20 employed the structural function method to establish a direct relationship between roughness and the parameters D and G in the form below:

When various values of \({R_{\text{a}}}\)are assigned to roughness, the fractal dimension and characteristic scale obtained from the empirical formula are compared with those calculated using the structural function method. The comparative results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 indicates that the fractal dimensions calculated using the empirical expression and the structural function method have a relative error consistently below 0.8%. This suggests that the empirical expression is reliable for determining fractal dimensions. However, the characteristic scale G, calculated using these methods, shows significant discrepancies. Given that the characteristic scale strongly depends on the surface roughness, it is necessary to re-establish the relationship between surface roughness and G. This process is crucial to accurately simulate the distribution of micro-asperities using the M-B fractal function.

Using a single-objective optimization algorithm for fitting and solving, a relationship between roughness Ra and the characteristic scale G is established through the following optimization steps:

-

(1)

Determine the basic parameters \({n_{\hbox{min} }}\) and \({n_{\hbox{max} }}\) according to the M-B fractal model.

-

(2)

Given random surface roughness values Ra, calculate the fractal dimension D using Eq. (5), and establish the initial value of the characteristic scale G employing Eq. (6).

-

(3)

Determine the surface roughness distribution according to Eq. (1).

-

(4)

Based on the surface topography curve theory, we calculate the simulated roughness value Ra1. Through an optimization solution, we determine the characteristic scale coefficient G, ensuring that the relative error between Ra1 and the actual roughness value Ra remains below 1%. Furthermore, we utilize the structural function algorithm to ascertain the fractal dimension D1 and the characteristic scale coefficient G1.

-

(5)

The relative error between the fractal dimension D, calculated using the empirical formula (4–5), and the fractal dimension D1, determined by the structural function method, has been found to be less than 1%. This level of accuracy makes the empirical formula directly applicable. However, there is a significant discrepancy between the characteristic scale coefficient G and the coefficient G1 obtained through the structural function algorithm. This discrepancy necessitates a re-evaluation of the coefficient through fitting to determine its accurate value.

-

(6)

Repeat (2)\(\sim\)(5) to obtain the fractal dimension D and the characteristic scale coefficient G corresponding to any Ra value, and the fractal dimension D1 and the characteristic scale coefficient G1 determined by the structural function method.

-

(7)

Through polynomial fitting, we establish the relationship between Ra and the characteristic scale coefficient G, revise the structural function algorithm, and construct the accurate M-B fractal prediction model.

Experimental validation of the modified model

In the present study, five cylindrical GCr15 test specimens with varying roughness levels were prepared. These specimens were analyzed using a laser confocal scanning analyzer (LSM800, Car Zeiss, Germany) to measure their axial surface profiles. The sampling length was set to 1 mm, with 1000 discretized sampling points. Each specimen was measured three times in different directions to obtain accurate roughness values and contour morphology. Figures 3 and 4 display the measurement instrument and the resulting surface morphology.

The measured surface profile data were exported, and the fractal dimension and characteristic scale were calculated on the MATLAB platform.

Table 2 indicates that the characteristic scale coefficient G1, obtained using the modified structural function method, and G obtained from the modified empirical expression both had a relative error of less than 7.36%. This represents a significant improvement in accuracy compared to the values provided in Table 1. This observation demonstrates that a precise relationship between roughness \({R_{\text{a}}}\)and the characteristic scale G can be established by modifying the empirical expression, providing a solid foundation for accurately constructing the M-B function suitable for engineering applications.

Construction of cycloidal gear and pin tooth morphology model

Constructing a rough surface topography model involves introducing non-stationary, randomly distributed micro-protrusions onto a smooth surface. The smooth surface is represented by a vector function, while the height of the micro-protrusions is described by the M-B function. This study integrates the vector function with the M-B function to create the morphology model of cycloidal gear and pinion teeth.

According to differential geometry, the equation of a two-dimensional plane curve can be mathematically expressed in the form below22:

Where i and j are unit vectors along the coordinate axes, and \(x\left( \theta \right)\) and \(y\left( \theta \right)\) are continuous functions within their domain of definition.

Combining the M-B function with the equation of a two-dimensional plane curve, the two-dimensional section equation of an isotropic rough surface can be expressed as:

Where \(z\left( s \right)\) represents the height of the micro-convex body, m is the normal vector at a specific point on the curve, and the sign ± indicates the concavity or convexity of the curve: the positive sign corresponds to concave regions, while the negative sign applies to convex regions.

The morphology model of the pin tooth

The shape of the pin tooth is a cylinder, and its vector function can be expressed as \({\varvec{r}}\left( \theta \right)=r\cos \left( \theta \right){\varvec{i}}+r\cos \left( \theta \right){\varvec{j}}\), where r denotes the cylinder radius. The unit normal vector at each point on the arc is \(\left( {\cos \left( \theta \right),\sin \left( \theta \right)} \right)\).

According to the basic parameters listed in Table 4, D and G are 1.588 and \(2.443 \times {10^{ - 6}}\) mm, respectively. By integrating Eqs. (7) and (8), the model illustrating the tooth surface morphology of the pin tooth and the height distribution of the micro-protrusions is depicted in Fig. 5. It is observed that the surface of the pin tooth is no longer smooth due to the presence of micro-convex body. The maximum height of these micro-convex body is \(1.394{\text{\varvec{\upmu}m}}\), while the deepest depression measures \(1.697{\text{\varvec{\upmu}m}}\).

Morphological model of cycloidal gear

The tooth profile of cycloidal gear, including equidistant modification and offset modification25, can be mathematically expressed as follows:

Where \({\theta _{\text{c}}}={\tan ^{ - 1}}\frac{{{k_1}\sin {\varphi _1}}}{{1 - {k_1}\sin {\varphi _1}}}\), \({k_1}=\frac{{e \cdot {z_{\text{p}}}}}{{{r_{\text{p}}}+\Delta {r_{\text{p}}}}}\), \(\alpha\) is the tooth profile parameter of cycloidal gear, \(\Delta {r_{\text{p}}}\) represents the offset modification amount, and \(\Delta {r_{{\text{rp}}}}\) denotes equidistant modification.

The curvature radius of the cycloidal gear tooth profile25 is:

It should be indicated that when \({\rho _{2i}}>0\), the curve is concave, otherwise, the curve is convex.

Combining Eqs. (7), (8), (9), (10), and (11), yields a single-tooth morphology model of the cycloidal gear.

Figure 6 illustrates the fractal profile of a single cycloidal tooth, revealing that the cycloidal tooth profile encompasses segments with both concave and convex curvatures.

Figure 7 shows the height distribution of micro-convex body on the cycloidal tooth surface, revealing that the surface is, in fact, uneven.

Figure 8 is a physical diagram of the cycloid wheel in engineering practice, from which the actual tooth profile shape of the cycloid wheel can be directly seen.

Determination of curved surface contact coefficient between cycloidal gear teeth and pin teeth

Construction of curved surface contact coefficient between cylindrical surface and cylindrical surface

Existing fractal contact models typically calculate the contact area of micro-convex body based on interactions between rough and smooth flat surfaces. However, when the rough surface is curved, the contact area is significantly reduced, leading to substantial changes in the contact load. Thus, determining the curved surface contact coefficient after the surface has been curved becomes critically important.

Figure 9 illustrates the Hertz contact between two cylinders. Cylinders 1 and 2 have a radius of \({R_1}\) and \({R_2}\), respectively. Both cylinders share a width of B. Under the influence of the normal load F, the Hertz contact width between the two cylinders is represented by AB.

According to Hertz’s contact theory26, for two curved surfaces in contact, the Hertz contact width and the theoretical contact area can be determined using the following expressions:

The comprehensive radius of curvature R is given by \(R={1 \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 {\left( {\frac{1}{{{R_1}}} \pm \frac{1}{{{R_2}}}} \right)}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\left( {\frac{1}{{{R_1}}} \pm \frac{1}{{{R_2}}}} \right)}}\), when two curved surfaces are in external contact, a positive value is applied; conversely, for internal contact, a negative value is applied; \(F^{\prime}=\frac{F}{B}\) denotes the load per unit linear length; E is the equivalent elastic modulus of two curved surfaces.

The curved surface contact coefficient of the contacting cylindrical surfaces19 is defined as follows:

Where \({S_{\text{h}}}\) and \(\sum S\) are the theoretical contact area and the sum of the nominal contact areas of the two curved surfaces, respectively. Moreover, \(\sum S\) refers to the sum of the contact half-width and the developed area of the circular arc, resulting from the intersection of the two cylinders.

Where \({S_1}=2{R_1} \cdot \arcsin \left( {\frac{{0.5 \cdot {a_{\text{h}}}}}{{{R_1}}}} \right) \cdot B\), and\({S_2}=2{R_2} \cdot \arcsin \left( {\frac{{0.5 \cdot {a_{\text{h}}}}}{{{R_2}}}} \right) \cdot B\). It should be indicated that if the curvature radius of surface 2 tends to infinity, the sum of the nominal contact areas of the two surfaces is \({S_1}\), which is equivalent to the contact between surface 1 and the plane. On the other hand, if the curvature radius of surface 2 tends to zero, it is equivalent to a surface contacting a point, which has no significance in engineering applications.

Combining Eqs. (12), (13) and (14) yields the surface contact coefficient of two cylindrical curved surfaces as follows:

Analysis of contact proportional coefficient

The radius of cylinder 1 is 10 mm; The radius range of the cylindrical surface 2 is (0,10); The cylinder width is 10 mm; The normal load on two cylinders is 1000 N; The comprehensive elastic modulus is\(E=206{\text{GPa}}\); Fig. 10 shows the \({\lambda _{\text{c}}} - {R_2}\) curve.

Figure 10 demonstrates that when\({R_1}\)is constant, the inner and outer contact widths \({\lambda _{\text{c}}}\)increase as \({R_2}\)increases. Initially, the surface contact coefficient grows rapidly before stabilizing. When the radii of the two cylindrical surfaces are equal, the internal surface contact coefficient is greater than the external surface contact coefficient. This indicates that the internal contact area is larger and the contact stress is lower during internal contact compared to external contact. This behavior aligns with Hertz’s contact theory, which states that when two cylindrical surfaces with the same curvature undergo internal contact, the coefficient \({\lambda _{\text{c}}}\)equals 1. This signifies that the surfaces are completely enveloping each other and are in contact at every point. Table 3 shows that as the load increases, the surface contact coefficient remains constant, which provides a foundation for subsequent fractal contact analysis.

This analysis demonstrates that the surface contact coefficient constructed in this study is reasonable.

Analysis of curved surface contact coefficient of cycloidal pinwheel

Equation (11) reveals that the curvature radius of the cycloidal gear significantly influences the surface contact coefficient. Thus, analyzing the distribution of the cycloidal gear’s curvature radius is essential. Figure 11 illustrates this distribution.

Figure 11 shows that the curvature of the cycloidal gear is less than 0, indicating that the curve is concave outward. In this state, the cycloidal gear engages in external meshing with the pin teeth. At the position (-0.2308, -0.3984), the curvature of the cycloidal gear matches that of the pin teeth, signifying external contact with the same curvature. At the position (0.0029, -0.0019), the curvature equals 0, indicating a transition from an outwardly convex to an inwardly concave shape for the cycloidal gear. At this point, the curvature radius of the cycloidal gear approaches infinity, equivalent to the pin teeth making contact with a plane. When the curvature of the cycloidal gear is greater than 0, the gear engages in internal meshing with the pin teeth, allowing for the possibility of internal contact with the same curvature. Equation (15) can also address this scenario.

Figure 12 illustrates the engagement process between the cycloidal gear and the pin tooth, revealing the variations of the contact coefficient from the tooth crest to the tooth root. It is observed that in the external meshing stage, the contact coefficient is 0.48. As the gear reaches the curvature equilibrium point, the contact coefficient rises to 0.75. It then continues to increase, reaching 0.92 during the internal meshing stage. Throughout the entire engagement interval, the contact coefficient in the internal meshing stage remains higher than that in the external meshing stage.

MB fractal contact model

Considering the scale characteristics of micro-convex body, a fractal contact model for the contact interface is established. For any the frequency index n:

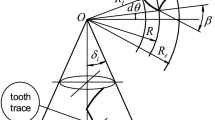

Figure 13 schematically shows the contact deformation between micro-convex body and a rigid plane. In this diagram, l is the length of the micro-convex body base, \({l_{\text{t}}}\) is the truncated length of the micro-convex body, \({l_{\text{r}}}\) is the real contact length of the micro-convex body, \({R_n}\) is the curvature radius of the top of the micro-convex body, \({\delta _n}\) is the height of the micro-convex body, and \({w_n}\) is the bearing deformation of the micro-convex body.

The asperities before deformation can be represented as:

Based on this expression, the curvature radius at the top of the micro-convex body on the fractal surface is:

The expressions for the deformation \({w_n}\) and height \({\delta _n}\) of the micro-convex body are:

Elastic deformation stage

Based on Hertz contact theory26, when elastic deformation occurs, the contact area and contact load of a single micro-convex body are given by:

The critical elastic deformation is:

Where H is the hardness of the softer material, and K is the hardness coefficient \(K=0.454+0.41\mu\).

Considering friction, the elastic critical contact area of the convex body can be obtained using the following expression:

Combining Eqs. (16), (18), (21), and (22) yields the relationship between the contact load and the contact area during elastic deformation.

When the micro-convex body is elastically deformed, the relationship between the cross-sectional area of the micro-convex body and the real contact area is:

Combining Eqs. (24) and (26) yields the relationship between the elastic critical cutting area and the elastic critical cross-sectional area. This can be expressed in the form below:

Similarly, the relationship between the elastic contact load and the elastic cutting area can be derived as:

Elastic-plastic deformation

Kogut and Etsion27,28 analyzed the elastic-plastic contact of spherical convex bodies. When the deformation magnitude \({w_{{\text{nec}}}}<{w_{{\text{nep1}}}} \leqslant 6{w_{{\text{nec}}}}\), the micro-convex body is in the first stage of elastoplastic deformation. During this stage, the contact area and the corresponding contact load are given by:

When the deformation magnitude exceeds\(6{w_{{\text{nec}}}}<{w_{{\text{nep}}2}} \leqslant 110{w_{{\text{nec}}}}\), the micro-convex body enters the second stage of elastoplastic deformation. At this stage, the contact area and the respective contact load are characterized by:

The first and the second elastic-plastic critical areas are denoted as \({a_{{\text{nepc1}}}}=7.1197{a_{{\text{nec}}}}\) and \({a_{{\text{nepc2}}}}=205.3827{a_{{\text{nec}}}}\), respectively.

When the contact is in the first and second elastic-plastic stage:

It should be indicates that during the elastic-plastic deformation stage, the relationships between the sides of a right-angled triangle are utilized.

The expression of the cut-off area is:

The deformation amplitude of a micro-convex body is significantly smaller than the curvature radius at its tip, so the truncated area can be expressed as:

The first and second-stage elastic-plastic cross-sectional area can be derived by combining Eqs. (29), (31), and (37).

The relationship between the first elastic-plastic critical truncated area, the second elastic-plastic critical truncated area, and the elastic critical truncated area are given by:

The relationship between the first elastic-plastic contact load and the truncated area is expressed as:

The relationship between the second elastic-plastic contact load and the truncated area is as follows:

Complete plastic deformation stage

When\({w_{{\text{npc}}}}>110{w_{{\text{nec}}}}\), the convex body exhibits a plastic deformation. At this stage, the contact area and contact load can be described as:

According to Hertz’s theory, in the complete plastic deformation stage:

Meanwhile, the correlation between complete plastic contact load and plastic sectional area can be expressed in the form below:

Determination of the deformation state of different grades of micro-convex bodies

The micro-convex body is elastically deformed, and if the maximum deformation of the micro-convex body is \({\delta _{\text{n}}} \leqslant {w_{{\text{nec}}}}\)

Bring formulas (16), (18), (20) and (23) into (48)

By solving Eq. 49, the critical grade \({n_{{\text{nec}}}}\)of elastic deformation of micro-convex body can be obtained15.

The first and second elastic-plastic critical grades of the micro-convex body are

The deformation behavior of a micro-asperity varies depending on its grade.

for \({n_{\hbox{min} }}<n \leqslant {n_{{\text{nec}}}}\), the micro-asperity undergoes only elastic deformation.

for \({n_{{\text{nec}}}}<n \leqslant {n_{{\text{epc1}}}}\), the micro-asperity experiences elastic deformation and the first stage of elastic-plastic deformation.

for \({n_{{\text{nepc1}}}}<n \leqslant {n_{{\text{nepc2}}}}\), the micro-asperity undergoes elastic deformation, the first and the second stages of elastic-plastic deformation.

for \({n_{{\text{nepc2}}}}<n \leqslant {n_{\hbox{max} }}\), the micro-asperity undergoes elastic deformation, the first and the second stages of elastic-plastic deformation.

Area distribution function of micro-convex body

According to fractal theory, when the contact plane becomes curved, the distribution function of the contact area for micro-convex body on a sliding friction surface can be expressed in the form below:

Where \(\psi\) is the fractal region expansion coefficient; \(a_{{\text{l}}}^{\prime }\) is the maximum asperity cross-sectional area; \({A_{\text{r}}}\) is the real contact area of the sliding friction surface.

The functional relationship between the regional expansion coefficient \(\psi\) and the fractal dimension D is given by:

The real contact area for fractal interfaces related to scale depends on the maximum micro-convex body truncation area, determined by the micro- convex body level. The contact area distribution function for micro- convex body of different levels can be defined as \({n_{\text{n}}}({a^\prime })\) and \({n_{\text{n}}}({a^\prime })={Q_{\text{n}}}n({a^\prime })\), with the expression for\({Q_{\text{n}}}\)provided in reference15.

Where \(a_{{\text{l}}}^{\prime }=\hbox{max} \left( {a_{{{\text{nl}}}}^{\prime }} \right)\) and \({n_{\hbox{min} }} \leqslant n \leqslant {n_{\hbox{max} }}\).

Real contact area and contact load

The real contact area is defined as:

Where \({A_{{\text{re}}}}\) is the elastic contact area; \({A_{{\text{rep1}}}}\) is the first elastic-plastic contact area; \({A_{{\text{rep2}}}}\) is the second elastic-plastic contact area; and \({A_{{\text{rp}}}}\) denotes the completely plastic contact area.

The total contact load is defined as:

Where \({P_{{\text{re}}}}\) is the elastic contact load; \({P_{{\text{rep1}}}}\) is the first elastic-plastic contact load; \({P_{{\text{rep2}}}}\) is the second elastic-plastic contact load; and \({P_{{\text{rp}}}}\)is the complete plastic load.

Where \({g_1}\left( D \right)=\frac{D}{{2 - D}}{\psi ^{{\text{1-D/2}}}}\) represents a constant related to fractal dimension;\({g_2}\left( D \right)=\frac{{2E{\pi ^{0.5}}{G^{{\text{D-1}}}}}}{{3\sqrt 2 }}\frac{D}{{3 - D}}{\psi ^{{\text{1-D/2}}}}\), \({g_3}\left( D \right)={\text{0}}{\text{0.3433}}KH\frac{D}{{2.85 - D}}{\psi ^{{\text{1-D/2}}}}\) and \({g_4}\left( D \right)={\text{0}}{\text{0.4667}}KH\frac{D}{{2.5260 - D}}{\psi ^{{\text{1-D/2}}}}\)is a constant related to fractal dimension and material parameters.

Analysis of the contact characteristics of cycloidal pinwheels

The nominal contact area of a rough surface is denoted by \({A_{\text{a}}}={\left( {{L \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {L {{\gamma ^{{\text{n}}\hbox{min} }}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\gamma ^{{\text{n}}\hbox{min} }}}}} \right)^2}\). The dimensionless real contact area is represented as\(A_{{\text{r}}}^{*}={{{A_{\text{r}}}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{A_{\text{r}}}} {{A_{\text{a}}}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{A_{\text{a}}}}}\), and the dimensionless contact load is denoted by \(F_{{\text{r}}}^{*}={{{F_{\text{r}}}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{F_{\text{r}}}} {\left( {E{A_{\text{a}}}} \right)}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\left( {E{A_{\text{a}}}} \right)}}\). The basic parameters for the cycloidal pinwheel are presented in Table 4. Both the cycloidal pinwheel and pin teeth have a surface roughness of 0.4 \({\text{\varvec{\upmu}m}}\), and the hardness of the tooth surface is measured at 750 MPa.

Influence of microscopic characteristics on contact characteristics

Parameters D and G are the primary determinants in defining the shape and size of micro-protrusions on rough surfaces. These parameters exhibit a direct correlation with the surface roughness. The impact of surface roughness on the contact performance between two surfaces is illustrated in Fig. 14.

It is observed that as the surface roughness of the two contacting surfaces increases, the elastic critical load and the first and second elastoplastic critical loads gradually decrease, with the rate of decrease becoming progressively smaller.

Figure 15 reveals that an increase in roughness results in a gradual decline of the dimensionless real contact area. This observation may be attributed to the enhanced roughness causing micro-protrusions to become taller, subsequently decreasing the number of micro-protrusions that engage in actual contact. Consequently, the overall actual contact area reduces.

Influence of macroscopic parameters on contact characteristics

The cycloidal gear tooth profile is quite intricate, featuring a mix of concave and convex contour curves. During engagement with the pin tooth, the gear undergoes both external and internal meshing. Therefore, it is crucial to examine the effects of various macroscopic parameters on the contact performance of the engaging tooth surfaces.

Figure 16 illustrates a curve distribution diagram reflecting the influence of eccentricity on the load within the meshing interval. The diagram reveals that at eccentricities of 0.9 mm and 1.0 mm, the dimensionless load during meshing gradually decreases. This decrease aligns with the transition from external to internal meshing as the cycloidal pinwheel engages. However, at an eccentricity of 1.1 mm, the dimensionless load initially increases slightly before rapidly decreasing, resulting in more significant load fluctuations throughout the meshing interval and leading to unstable power transmission.

Figure 17 illustrates the influence of pin tooth radius on the load within the meshing interval. It is observed that as the pin tooth radius increases, the dimensionless contact load across the engagement zone decreases steadily. This observation reflects the transition from external engagement at the tooth crest to internal engagement with the cycloidal gear. Notably, the loads during the external engagement phase are higher than those in the internal engagement phase, consistent with classical Hertz contact theory. When the pin tooth radius expands from 1.5 mm to 2.5 mm, the dimensionless contact load decreases gradually but then rises rapidly between 2.5 mm and 3.5 mm. Throughout the engagement range, significant fluctuations in load amplitude occur, leading to unstable transmission. Therefore, a careful selection of the pin tooth radius can reduce the contact load between the pin tooth and the cycloidal gear, enhancing the system’s bearing capacity.

Figure 18 depicts the influence of the pin tooth distribution circle radius on the meshing interval load. The graph indicates that the dimensionless contact load decreases gradually as the radius of the pin tooth distribution circle increases. Under the same distribution circle radius, the dimensionless contact load along the meshing interval also gradually decreases, suggesting that increasing the radius of the pin tooth distribution circle appropriately can reduce the load in the meshing area and improve bearing capacity.

Influence of micro-convex level on contact characteristics

Figure 19 shows that as the minimum frequency index of micro-protrusions increases, the proportion of the elastic contact area decreases gradually, while the proportions of both the first and second elastoplastic contact areas increase. When this index exceeds 15, the proportion of the elastic contact area decreases more rapidly. Concurrently, the proportion of the first elastoplastic contact area increases quickly before stabilizing, and the proportion of the second elastoplastic contact area also rises rapidly. During the sliding wear process, the contact state between interacting surfaces significantly impacts wear. A larger proportion of elastic contact areas is more conducive to reducing wear. Thus, selecting an appropriate frequency index for the micro-protrusions is essential for minimizing wear on the contacting surfaces.

Conclusion

This paper integrates theoretical analysis and experimental methods to establish a clear relationship between surface roughness and characteristic scale. It introduces a surface contact coefficient model for evaluating complex surface contacts and investigates the effects of microscopic parameters, cycloidal pinwheel design parameters, and the hierarchy of micro-protrusions on the contact performance of cycloidal pinwheels. The main achievements of this article can be summarized as follows:

-

(1)

By integrating theoretical analysis with experimental validation, this study utilizes an optimization algorithm to determine the characteristic scale. This method enhances the traditional structural function technique, establishing a definitive relationship between surface roughness and the scale of micro-features.

-

(2)

Considering the curvature variability of the cycloidal gear tooth profile, a surface contact coefficient model applicable to internal and external contacts with arbitrary curvature is developed. The study also examines the variation of the surface contact coefficient within the meshing interval of cycloidal pinwheels.

-

(3)

A fractal contact model based on the dimensions of micro-protrusions is created, allowing for the analysis of micro-scale parameters’ effects on elastoplastic critical loads and the real contact area. Additionally, the study analyzes the impact of macroscopic parameters of the cycloidal pinwheel on the load within the engagement zone. It also clarifies the influence of the minimum frequency index of micro-protrusions on surface contact performance.

The study paves the way for a detailed analysis of the actual contact characteristics at the meshing interface of cycloidal pinwheels. It provides a basis for enhancing the elastic contact ratio of the contact surface and diminishing tooth surface wear.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Xu, L. X. & Yang, Y. H. Dynamic modeling and contact analysis of a cycloid-pin gear mechanism with a turning arm cylindrical roller bearing. Mech. Mach. Theory. 104, 327–349 (2016).

Xu, L. X., Chen, B. K. & Li, C. Y. Dynamic modelling and contact analysis of bearing-cycloid-pinwheel transmission mechanisms used in joint rotate vector reducers. Mech. Mach. Theory. 137, 432–458 (2019).

Li, X. et al. Analysis of a cycloid speed reducer considering tooth profile modification and clearance-fit output mechanism. J. Mech. Des. 139 (3), 033303 (2017).

Zhang, R., Zhou, J. & Wei, Z. Study on transmission error and torsional stiffness of RV reducer under wear. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 36(8), 4067–4081 (2022).

Wang, J., Gu, J. & Yan, Y. Study on the relationship between the stiffness of RV reducer and the profile modification method of cycloid-pin wheel. Intell. Robot. Appl. 9834, 721–735 (2016).

Yang, Y. H. et al. Analysis of the characteristics of torsional stiffness of RV reducer. J. Tianjin Univ. (Nat. Sci. Eng. Technol. Ed.). 48(2), 111–118 (2015).

Bhushan, B. & Ko, P. L. Introduction to tribology. Appl. Mech. Rev. 56(1), B6–B7 (2003).

Majumdar, A. & Bhushan, B. Fractal model of elastic-plastic contact between rough surfaces. (1991).

Majumdar, A. & Bhushan, B. Role of fractal geometry in roughness characterization and contact mechanics of surfaces. (1990).

Bhushan, B. & Majumdar, A. Elastic-plastic contact model for bifractal surfaces. Wear. 153(1), 53–64 (1992).

Wang, S. & Komvopoulos, K. A fractal theory of the interfacial temperature distribution in the slow sliding regime: Part I—Elastic contact and heat transfer analysis (1994).

Wang, S. & Komvopoulos, K. A fractal theory of the interfacial temperature distribution in the slow sliding regime: Part II—multiple domains, elastoplastic contacts and applications. (1994).

Ding, X. X., Yan, R. Q. & Jia, Y. L. Construction and analysis of fractal contact mechanics model for rough surface based on base length. Tribology. 34(04), 341–347 (2014).

Wei, L., Liu, Q. H. & Zhang, P. G. Sliding fraction contact mechanics model based on fractal theory. J. Mech. Eng. 48(17), 106–113 (2012).

Yuan, Y. et al. A revised Majumdar and Bushan model of elastoplastic contact between rough surfaces. Appl. Surf. Sci. 425, 1138–1157 (2017).

Chen, J. J. et al. Scale dependent normal contact stiffness fractal model of joint interfaces. J. Mech. Eng. 54(21), 127–137 (2018).

Yu, X. et al. A revised contact stiffness model of rough curved surfaces based on the length scale. Tribol. Int. 164, 107206 (2021).

Zhan, H., Chen, Q. & Huang, K. Fractal model of normal contact stiffness between two cylinders’ joint interfaces. J. Mech. Eng. 47(07), 53–58 (2011).

Chen, Q. et al. Research on fractal contact model for contact carrying capacity of two cylinders’ surfaces considering friction factors. J. Mech. Eng. 52(07), 114–121 (2016).

Chen, Q. et al. Research on fractal model of normal contact stiffness between two spheroidal joint surfaces considering friction factor. Tribol. Int. 97, 253–264 (2016).

Ma, D. Q. et al. Sliding fraction contact mechanics model of the involute arc cylindrical gear based on fractal theory. J. Mech. Eng. 52(15), 121–127 (2016).

Han, J., Li, W. & Wang, Z. J. Surface morphology models of cycloid and pin teeth based on fractal theory and differential geometry. J. Xi’ Jiaotong Univ. 51(11), 97–105 (2017).

Han, J., Li, W. & Dong, W. Fractal contact model for cycloid tooth and pin tooth considering friction factors. China Mech. Eng. 30(13), 1568–1576 (2019).

Yang, R. S., Zhang, Y. M. & Sun, S. Q. Research on contact stiffness of cycloid needle wheel based on fractal theory model. Adv. Eng. Sci. 52(01), 126–133 (2020).

Wang, Y. Q. et al. Multi tooth meshing characteristics and load bearing contact analysis method of cycloidal-pin wheels. China Mech. Eng. 34(10), 1151–1158 (2023).

Johnson, K. L. Contact Mechanics79–128 (Cambridge University Press, 1985).

Morag, Y. & Etsion, I. Resolving the contradiction of asperities plastic to elastic mode transition in current contact models of fractal rough surfaces. Wear. 262(5–6), 624–629 (2007).

Kogut, L. & Etsion, I. Elastic-plastic contact analysis of a sphere and a rigid flat. J. Appl. Mech. 69(5), 657–662 (2002).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Long Men laboratory’s leading-edge research project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W. Y wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Wei, B., Wang, Z. et al. A revised elastic-plastic contact model of cycloidal pinwheel based on length scale. Sci Rep 14, 27116 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76572-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76572-x