Abstract

Electrical storm (ES) is a life-threatening condition of recurrent ventricular arrhythmias (VA) in a short period of time. Percutaneous stellate ganglion blockade (SGB) is frequently used – however the efficacy is undefined. The objective of our systematic review was to determine the efficacy of SGB in reducing VA events and mortality among patients with ES. A search of Medline, EMBASE, Scopus, CINAHL and CENTRAL was performed on February 29, 2024 to include studies with adult patients (≥ 18 years) with ES treated with SGB. Our outcomes of interest were VA burden pre- and post-SGB, and in-hospital/30-day mortality. A total of 553 ES episodes in 542 patients from 15 observational studies were included. Treated VAs pre- and post-SGB were pooled from eight studies including 383 patients and demonstrated a decrease from 3.5 (IQR 2.25–7.25) to 0 (IQR 0–0) events (p = 0.008). Complete resolution after SGB occurred in 190 of 294 patients (64.6%). Despite this, in-hospital or 30-day mortality remained high occurring in 140 of 527 patients (random effects prevalence 22%). Repeat SGB for recurrent VAs was performed in 132 of 490 patients (random effects prevalence 21%). In conclusion, observational data suggests SGB may be effective in reducing VAs in ES. Definitive studies for SGB in VA management are needed.

Study protocol: PROSPERO - registration number CRD42023430031.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Electrical storm (ES) is a life-threatening condition defined by three or more sustained or treated ventricular arrhythmia (VA) events within 24-hours1,2,3,4. ES is not uncommon, occurring in 3.9% of patients with primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD) and in 10.5% of the secondary prevention population5. Despite advances in cardiac critical care and catheter ablation techniques, ES continues to pose significant challenges for clinicians, especially in cases where traditional anti-arrhythmic drugs (AAD) fail to provide adequate control. Autonomic dysregulation from chronic heart disease along with the adrenergic surge following electrical shocks for treatment of arrhythmias results in increased sympathetic tone6. As the autonomic nervous system has a significant adverse influence on the pathophysiology of VAs, sympathetic suppression has been proposed as a therapeutic target in patients with ES7,8,9,10.

The most common approach for sympathetic blockade involves the use of non-selective beta-blockers, unless contraindicated or not tolerated, and sedative agents with some requiring invasive mechanical ventilation to achieve arrhythmic suppression11,12. Neuromodulation procedures have been considered as an alternative treatment method with percutaneous stellate ganglion blockade (SGB) being the most commonly used technique in ES12. The stellate ganglion (also known as cervicothoracic ganglion) provides sympathetic innervation for the heart13. Located on the anterior surface of the longus colli muscle in the neck, it can be readily and safely injected under ultrasound guidance as a bedside procedure for adrenergic suppression14. SGB was initially used for treatment of long QT syndrome, but there has been increasing literature supporting its use in ES1,7,15,16.

Current evidence supporting SGB in ES is limited to mostly case reports and small observational cohort studies. The objective of this systematic review is to determine the effectiveness of SGB in reducing VA burden and mortality in patients with ES.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance to the Preferred Reported Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement17. The protocol was registered with the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO CRD42023430031).

Search strategy

We completed a literature search of five databases (Medline, EMBASE, Scopus, CINAHL and CENTRAL) from inception to May 28, 2023. The search strategy was designed by an experienced librarian (VL) using a combination of free text words and Medical Subject Heading terms (Supplementary Methods). Manual search of eligible articles’ reference lists and relevant review articles was done to identify additional studies. No restrictions were placed on date or language of publication. A grey literature search was not completed, but conference abstracts from comprehensive database search were included during study selection. An updated search was completed on February 29, 2024.

Study selection

Abstract and title screening was preformed independently by two reviewers (two of PM, NQ, NB, MM, WK) using Covidence (Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health information, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org). Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (PM or NQ). Full-text screening was completed independently by two reviewers (PM, NQ) with disagreements resolved by consensus. Covidence removed duplicates prior to manual screening; no automation tools were used during screening.

We included published full-text studies and conference abstracts meeting the following inclusion criteria: (1) Included adult patients (≥ 18 years of age) with ES; (2) received percutaneous SGB for treatment of ES; and (3) reported response to therapy (before and after ventricular arrhythmia, or control comparator) or mortality. A comparator/control arm was not required, and single cohort studies were included. Studies that used surgical sympathectomy for SGB or studies which had a sample size of less than 10 patients were excluded.

The primary outcomes were response to SGB defined by VA burden or recurrence and in-hospital mortality. The VA burden and recurrence was defined by comparison of the number of total and treated VA events before and after SGB, or to a control group. In cases where in-hospital mortality was not reported, we used 30-day mortality. Secondary outcomes included length of hospitalization and escalation in ES care. Escalation in care was defined by any of the following post-SGB: (1) mechanical circulatory support (MCS), including intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) or Impella; (2) cardiac transplantation; (3) deep sedation with mechanical ventilation; or (4) catheter ablation.

Data extraction

A pre-designed extraction form was created that included study design, patient demographics, SGB procedure details and outcomes. Data collection was completed independently by two investigators (PM, NQ). Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Repeat SGB procedure and surgical sympathectomy were extracted post-hoc as it was a commonly reported outcome. Corresponding authors were emailed on July 9, 2023 for missing outcomes.

Risk of bias assessment

The ROBINS-I tool was pre-selected for risk of bias assessment according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention statement on non-randomized studies of interventions18. All studies report the VA burden as before and after SGB. As the current ROBINS-I tool was not developed for before-after studies, we changed to the NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After (Pre-Post) Studies With No Control Group (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools)19,20. This tool includes twelve yes/no questions that are used to assess the internal validity of the studies. A quality rating of good, fair or poor is given based on the appraised strength of association between SGB and the outcome. Two investigators (PM, GW) adapted the tool to include an additional question to address the domain of bias due to confounding based on guidance from Chap. 25.5 of the Cochrane Handbook (Supplementary Methods)18. Two investigators (NQ, NB) independently answered the 13 questions and provided a quality rating. Disagreement in quality ratings were resolved by consensus. As all included studies had a before-after design, GRADE assessment was not completed due to the inherent low certainty of evidence in these study types.

Data synthesis and analysis

Data used for meta-analysis of the primary and secondary outcomes were pooled separately and independently to allow for the differences in reporting between individual studies. Population demographics are summarized by frequency. Continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviations (SD) if there was a normal distribution or with median and interquartile range (IQR) if non-normally distributed. In the case of studies using overlapping patient samples, preference was given to the updated study unless there was missing data only available in the initial study. The pre-designed method of analysis included summarizing the effect of SGB on outcomes using risk ratios.

For ventricular burden, total and treated VA events before and after SGB was analyzed using boxplots and paired T-tests of reported and calculated medians. Standardized mean differences (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated with a random effects model using the inverse variance method for the number VA before and after SGB. Response to therapy was summarized by frequency fixed and random effects modelling, using the following definition: (1) complete resolution – no VA events after SGB; (2) partial resolution – decrease in frequency in VA events after SGB and; (3) no resolution – equal or more VA events post-SGB. Death and all secondary outcomes were summarized with fixed and random effects modelling. All reported p-values are two-sided, and a value less than 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance. Analysis was performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Study selection and characteristics

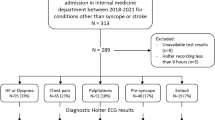

After screening 3035 studies, 15 studies met the inclusion criteria21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35 (Supplementary Fig. 1). The corresponding authors of one study provided additional data not included in the published manuscript29. Of the 15 studies, 13 were single arm cohort studies that report patient outcomes and arrhythmia burden before and after SGB21–24,26−29,31–35. The remaining two studies included a retrospective cohort study comparing outcomes between different neuromodulation techniques and a comparative study of bolus injection versus continuous infusion SGB25,30. The risk of bias assessment identified three studies of good quality26,32,34, eight of fair quality21,24,25,28,29,30,31,35 and four of poor quality22,23,27,33 (Supplementary Table 1).

Patient population and procedure details

A total of 553 ES events in 542 patients were included. Table 1 provides an overview of the included studies. The mean age of the study participants was 62.6 ± 3.7 years and included 91 (17%) females. Half of patients (52.0%) had ischemic heart disease and the median LVEF was 29% (interquartile range [IQR]: 23.5–31.8%). Twelve studies included patients with ES refractory to initial management21,23,24,25,26,27,29,30,32,33,34,35, while the other three studies did not report the refractoriness of ES. Treatment therapies used prior to SGB are summarized in Table 2. Patients were typically treated with amiodarone and lidocaine as first and second line AADs. In reported studies, MCS was used in 161 (33%) patients and deep sedation with mechanical ventilation was used in 148 (33%) patients prior to SGB.

Supplementary Table 2 describes the different techniques and anesthetic agents used during the procedure. Four studies exclusively performed SGB on the left stellate ganglion23,28,30,33. Three studies used a combination of bolus or continuous anesthetic infusions28,30,34, and one study compared the two techniques30. Anesthetic agents included lidocaine in 7 studies23,25,29,31,32,33,34, bupivacaine in 11 studies23–27,29−34 and ropivacaine in 7 studies21,25,28,29,30,32,34.Two studies used an injectate that included dexamethasone to prolong nerve blockade29,33.

Ventricular arrhythmia response

Total and treated VAs events are summarized for the individual studies in Table 3. VAs requiring external cardioversion/defibrillation or ICD therapy were pooled from eight studies involving 383 patients and showed a median (IQR) decrease from 3.5 (2.25–7.25) to 0 (0–0) events (Fig. 1A, p = 0.007)21,25,26,29,32–35 and a SMD of 1.07 (CI 0.85–1.29; I2 = 34.7%)21,25,26,32,33,35,36 during in-hospital follow-up. Follow-up at 24 h post-SGB, based on data from three studies with 141 patients, demonstrated a difference in the median number of episodes from 2.5 (2–4) to 0 (0-0.3; Fig. 1C, p = 0.05)25,29,32 and a SMD of 0.70 (CI 0.45–0.96; I2 = 0%)25,32. Similarly, the median number of total (treated and untreated) VAs before and after SGB decreased from 7.8 (5.2–9.5) to 0 (0–0)22,25,29,30,31,32 during in-hospital follow-up of 208 patients reported in six studies (Fig. 1B, p = 0.009) 22,25,29−3 with a SMD of 0.97 (CI 0.74–1.20; I2 = 0%)22,25,30,32. At 24 h post-SGB, data reported in four studies including 159 patients found a median (IQR) reduction from 7.8 (6-8.5) to 0 VAs (0-0.3; Fig. 1D, p = 0.036)25,29,30,32 with a SMD of 0.90 (CI 0.66–1.14; I2 = 0%)25,30,32. Complete resolution of VAs after SGB occurred in 220 of 326 (67.5%) with a random effects incidence of 70% (CI 59 − 80%). Repeat SGB for recurrent VAs occurred in 123 of 410 patients with a random effects incidence of 21% (CI 13 − 29%; Table 3).

Median ventricular arrhythmia events requiring external shock or ICD therapies before and after stellate ganglion block for in-hospital follow-up (A) and at 24 h post- stellate ganglion block (C), and median ventricular arrhythmia events before and after stellate ganglion block during in-hospital follow-up (B) and at 24 h post- stellate ganglion block (D). Abbreviations: ICD – implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, VA – ventricular arrhythmia.

Patient outcomes

Tables 4 and 5 pooled patient outcomes, and Supplementary Table 3 provides individual study outcomes. In-hospital or 30-day mortality occurred in 140 of 527 patients (26.7%) across 13 studies (Table 5) with a random effects incidence of 22% (CI 15 − 29%)21–24,26−32,34,35. Among 128 patients from five studies, MCS was required post-SGB in 11 patients (8.6%) with a random effects incidence of 7% (CI 2 − 11%)22,26,28,29,35. Additionally, 11 of 108 patients (10.2%) required de novo implementation of deep sedation and mechanical ventilation after SGB with a random effects incidence of 15% (CI -8 − 37%)24,26,29. Cardiac transplantation occurred in 19 of 107 (17.8%) reported in five studies22,24,30,31,35. Post-SGB catheter ablation was performed in 165 of 458 patients (36.0%) from eleven studies with a random effects incidence of 32% (CI 22 − 41%)22–26,28,30–32,34,35.

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies evaluating SGB in ES, we found a significant reduction in the total and treated VA events post-SGB. Notably, 70% and 19% of recipients had complete and partial resolution of VA events, respectively, while only 9% had no change in VA events. The in-hospital or 30-day mortality was 22% and escalation of therapy including MCS (7%), deep sedation with mechanical ventilation (15%) and cardiac transplantation (16%) were commonly used post-SGB. While the available published literature to date evaluating SGB is limited to observational studies, SGB appears effective at reducing subsequent VA events but there remains significant residual risk to patients given the high in-hospital/30-day mortality.

The use of SGB for sympathetic blockade in ES was first described more than two decades ago7,37. Despite this, there has been limited progress in developing a robust body of evidence for its use in ES. A prior systematic review and meta-analysis published in 2017 collected small case-series and case reports totalling 38 patients from 23 studies15. They reported a decrease from 10 ± 9.1 to 0.05 ± 0.22 treated VAs/day pre- and post-SGB respectively, with 24 of the 38 patients having complete resolution. Despite the weak quality of evidence, SGB has garnered recommendations for ES treatment in multiple reviews and holds a class IIb indication in the European Society of Cardiology’s Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death3 as well as multiple consensus statements4,38. As a result, SGB is currently performed in 82.5% of capable medical centres for treatment of ES and is most commonly performed in refractory ES cases12. Due to the progress in the body of evidence, a systematic reappraisal of SGB’s efficacy was necessary to establish a more conclusive understanding of its benefits and limitations. This is particularly true given heterogeneity in the timing of SGB and pre-SGB medical therapy given to ES patients.

This systematic review suggests a significant reduction in VA events following SGB. Although an immediate effect of SGB appears evident, it remains uncertain whether this effect translates to improved patient outcomes, especially in the absence of control comparators and randomized control trials (RCT). Although this study did not specifically evaluate safety, most complications of the SGB procedure itself are temporary with a small risk for neurovascular and infectious complications, and rarely mortality39. Furthermore, this meta-analysis highlights a high mortality rate of 26.6% despite being treated with SGB, reflecting the poor outcomes associated with medically-refractory ES occurring in patients with systolic dysfunction. In contrast, the International Electrical Storm Registry (ELECTRA) reports a lower one-year mortality of 14.8% and a study of propranolol versus metoprolol for the management of ES reported no deaths during its two-month follow-up period8,40. In the absence of a comparator, no conclusions can be made on the mortality effects of SGB. The high mortality rate identified in this study is likely related to the included patient population being higher risk with predominantly refractory ES, as well as competing risk of death from heart failure, shock and myocardial infarction. Furthermore, the patients included in our review were mostly men, had a history of ischemic heart disease and relatively young with a median age around 60 years. In the absence of more granular data, it is unclear if there is a difference in outcomes between sexes, etiology of heart disease, and age.

This study highlights the variability in SGB procedure techniques. Although the injectate typically includes one of three anesthetic agents (lidocaine, ropivacaine, or bupivacaine), many studies used different doses, combined anesthetics, and two added dexamethasone. Furthermore, the studies included had different methods for selecting the injection site, with some studies utilizing left and/or right stellate ganglions. There are potential physiologic differences between sites; right-sided injections were found to prolong the QT interval and have a marked decrease in heart rate while left-sided blockade decreases the QT interval without a significant change in heart rate41,42. Based on our study, there is insufficient data to comment on the efficacy of SGB based on site. Given that the current systematic review reports a repeat SGB injection frequency of 22.8%, it does raise the question whether a longer course of treatment with continuous infusions or routine scheduled repeat injections would yield greater benefits. Future high-quality RCTs with standardized techniques would provide more definitive results and their protocols will likely serve as the basis for creating a standardized approach. Lastly, the role and timing of catheter ablation or surgical sympathectomy is unclear in patients with ES, and the efficacy of SGB in combination with other therapies is unclear. The GANGlion Stellate Block for Treatment of Electric storRm (GANGSTER) trial is an ongoing double-blinded, sham-controlled RCT on left SGB with bupivacaine in management of ES (NCT05078684) that may provide further insights into the efficacy of SGB.

There are important limitations to consider in this study. First, all included studies in this review have an observational before-after design that has an inherent risk of bias due to confounding variables. While the pre-SGB cohort may in theory serve as control comparators, co-interventions such as AAD administration or sedation result in confounding and potentially an overestimation of effect; this may particularly be true for amiodarone, with its unique pharmacokinetics and delayed onset. This highlights the broader issue of the overall low-quality evidence in ES, where recommendations often stem from non-ES, animal, observational studies, or small RCTs2,4,12. Second, none of the studies included a control comparator, and the before/after single-arm study is a weaker study design. Although we found evidence that SGB decreases VA burden versus pre-SGB, it is not clear if SGB reduces the mortality rate or reduces the need for MCS or mechanical ventilation. Third, these studies have significant methodological heterogeneity due to the variability in SGB procedure techniques and we can not comment on an ideal injectate, site or method, and impact of underlying heart disease. Furthermore, there is no widely accepted risk of bias tool for before-after study designs. While we believe the adapted NIH tool used proved to be adequate, it is important to note that this method has not been validated.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis of SGB and ES identified a reduction in VA events following SGB. Despite its apparent therapeutic efficacy, this patient population remains at high-risk of short-term mortality. Randomized data is needed to establish SGB as a therapeutic approach to the management of ES.

Data availability

Data are available on request by contact through the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- ECMO:

-

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- ES:

-

Electrical storm

- IABP:

-

Intra–aortic balloon pump

- ICD:

-

Implantable cardioverter–defibrillators

- MCS:

-

Mechanical circulatory support

- NIH:

-

National Institutes of Health

- SGB:

-

Stellate ganglion block

- SMD:

-

Standardized mean differences

- VA:

-

Ventricular arrhythmia

References

Al-Khatib, S. M. et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death. Circulation. 138, e272–e391. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000549 (2018).

Deyell, M. W. et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Heart Rhythm Society Position Statement on the Management of Ventricular Tachycardia and Fibrillation in Patients With Structural Heart Disease. Canadian Journal of Cardiology 36, 822–836, doi: (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2020.04.004 (2020).

Zeppenfeld, K. et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: Developed by the task force for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Endorsed by the Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). European Heart Journal 43, 3997–4126, doi: (2022). https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac262 (2022).

Jentzer, J. C. et al. Multidisciplinary critical Care Management of Electrical Storm. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 81, 2189–2206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2023.03.424 (2023).

Guerra, F. et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator programming and electrical storm: results of the OBSERVational registry on long-term outcome of ICD patients (OBSERVO-ICD). Heart Rhythm. 13, 1987–1992 (2016).

Bode, F., Wiegand, U., Raasch, W., Richardt, G. & Potratz, J. Differential effects of defibrillation on systemic and cardiac sympathetic activity. Heart. 79, 560–567. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.79.6.560 (1998).

Nademanee, K., Taylor, R., Bailey, W. E., Rieders, D. E. & Kosar, E. M. Treating electrical storm: sympathetic blockade versus advanced cardiac life support-guided therapy. Circulation. 102, 742–747. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.102.7.742 (2000).

Chatzidou, S. et al. Propranolol Versus Metoprolol for treatment of electrical storm in patients with Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 71, 1897–1906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.056 (2018).

Gadhinglajkar, S., Sreedhar, R., Unnikrishnan, M. & Namboodiri, N. Electrical storm: role of stellate ganglion blockade and anesthetic implications of left cardiac sympathetic denervation. Indian J. Anaesth. 57, 397–400. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5049.118568 (2013).

Vaseghi, M. & Shivkumar, K. The role of the autonomic nervous system in sudden cardiac death. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 50, 404 (2008).

Martins, R. P. et al. Effectiveness of deep sedation for patients with intractable electrical storm refractory to antiarrhythmic drugs. Circulation. 142, 1599–1601. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047468 (2020).

Baldi, E. et al. Contemporary management of ventricular electrical storm in Europe: results of a European Heart Rhythm Association Survey. EP Europace. 25, 1277–1283. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euac151 (2022).

Zandstra, T. E. et al. Asymmetry and heterogeneity: Part and Parcel in Cardiac autonomic innervation and function. Front. Physiol. 12https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.665298 (2021).

Narouze, S., Vydyanathan, A. & Patel, N. Ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block successfully prevented esophageal puncture. Pain Physician. 10, 747–752 (2007).

Meng, L., Tseng, C. H., Shivkumar, K. & Ajijola, O. Efficacy of stellate ganglion blockade in managing electrical storm: a systematic review. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 3, 942–949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacep.2017.06.006 (2017).

Moss, A. J. & McDonald, J. Unilateral Cervicothoracic Sympathetic Ganglionectomy for the treatment of long QT interval syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 285, 903–904. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM197110142851607 (1971).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 88, 105906 (2021).

Sterne, J. A. C., McAleenan, H. M., Reeves, A. & Higgins, B. C. JPT. Chapter 25: Assessing risk of bias in a non-randomized study. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3 (updated February (2022). (2022).

Sterne, J. A. et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 355, i4919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919 (2016).

Ma, L. L. et al. Methodological quality (risk of bias) assessment tools for primary and secondary medical studies: what are they and which is better? Military Med. Res. 7, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-020-00238-8 (2020).

Dhanse, S. et al. Effectiveness of ultrasonography-guided cardiac sympathetic denervation in acute control of electrical storm: a retrospective case series. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol. 38, 610–616. https://doi.org/10.4103/joacp.JOACP_16_21 (2022).

Halawa, A. et al. Heart Rhythm 18, S440–S441, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2021.06.1087 (2021).

Kotti, K. et al. Ultrasound guided percutaneous left stellate ganglion block for ventricular arrhythmia storm in acute coronary syndrome following percutaneous coronary intervention: a case series. J. Arrhythmia. 35, 574–575. https://doi.org/10.1002/joa3.12276 (2019).

Lador, A. et al. Stellate ganglion instrumentation for pharmacological blockade, nerve recording, and stimulation in patients with ventricular arrhythmias: preliminary experience. Heart Rhythm. 20, 797–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2023.02.024 (2023).

Markman, T. M. et al. Neuromodulation for the treatment of refractory ventricular arrhythmias. JACC: Clin. Electrophysiol. 9, 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacep.2022.08.031 (2023).

Jiravsky, O. et al. Early ganglion stellate blockade as part of two-step treatment algorithm suppresses electrical storm and need for intubation. Hellenic J. Cardiol.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjc.2023.04.003 (2023).

Pasula, A., Ghosh, A. & Pandurangi, U. M. PO-04-232 < strong > PERCUTANEOUS STELLATE GANGLION BLOCKADE FOR ELECTRICAL STORM: LARGE SINGLE CENTRE EXPERIENCE. Heart Rhythm. 20https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2023.03.1229 (2023).

Patel, R. A., Condrey, J. M., George, R. M., Wolf, B. J. & Wilson, S. H. Stellate ganglion block catheters for refractory electrical storm: a retrospective cohort and care pathway. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 48, 224–228. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2022-104172 (2023).

Reinertsen, E., Sabayon, M., Riso, M., Lloyd, M. & Spektor, B. Stellate ganglion blockade for treating refractory electrical storm: a historical cohort study. Can. J. Anaesth. 68, 1683–1689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-021-02068-1 (2021).

Sanghai, S. et al. Stellate ganglion blockade with continuous infusion Versus single injection for treatment of ventricular arrhythmia storm. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 7, 452–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacep.2020.09.032 (2021).

Tian, Y. et al. Effective use of Percutaneous Stellate Ganglion Blockade in patients with Electrical Storm. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 12, e007118. https://doi.org/10.1161/circep.118.007118 (2019).

Chouairi, F. et al. A Multicenter Study of Stellate Ganglion Block as a Temporizing treatment for refractory ventricular arrhythmias. JACC: Clin. Electrophysiol.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacep.2023.12.012 (2024).

Cardona, X. R., Butnaru, D. S. & Ribero, O. F. G. Bloqueo De Ganglio Estrellado como una estrategia de manejo en cuidado paliativo en paciente con arritmias cardíacas terminales: Serie De Casos. Rev. Chil. Anest. 53, 66–72 (2024).

Savastano, S. et al. Electrical storm treatment by percutaneous stellate ganglion block: the STAR study. Eur. Heart J. ehae021https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae021 (2024).

Batnyam, U. et al. Safety and Efficacy of Ultrasound-guided sympathetic blockade by Proximal Intercostal Block in Electrical Storm patients. JACC: Clin. Electrophysiol.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacep.2023.12.006 (2024).

Savastano, S. et al. Electrical storm treatment by percutaneous stellate ganglion block: the STAR study. Eur. Heart J. 45, 823–833. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae021 (2024).

Grossman, M. A. Cardiac arrhythmias in Acute Central Nervous System Disease: successful management with stellate ganglion block. Arch. Intern. Med. 136, 203–207. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1976.03630020057012 (1976).

Kowlgi, G. N. & Cha, Y. M. Management of ventricular electrical storm: a contemporary appraisal. EP Europace. 22, 1768–1780. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euaa232 (2020).

Goel, V. et al. Complications associated with stellate ganglion nerve block: a systematic review. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med.https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2018-100127 (2019).

Guerra, F. et al. Abstract 18503: preliminary results from the Multicenter International Registry on Electrical Storm patients: the ELECTRA Study. Circulation. 136, A18503–A18503. https://doi.org/10.1161/circ.136.suppl_1.18503 (2017).

Egawa, H., Okuda, Y., Kitajima, T. & Minami, J. Assessment of QT interval and QT dispersion following stellate ganglion block using computerized measurements. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 26, 539–544 (2001).

Yokota, S., Taneyama, C. & Goto, H. Different effects of right and left stellate ganglion block on systolic blood pressure and heart rate. Open. J. Anesthesiology, 3(3), 143–147. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojanes.2013.33033 (2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.M., N.Q., F.D.R. G.W. and B.H. created the study protocol. P.M., N.Q., N.B., M.M., W.K., G.P.P., W.K., S.P., P.D., O.A.R. and R.J. completed study screening and data extraction. P.M., N.Q., N.B., G.W. completed risk of bias assessment. P.M. and E.L. completed data analysis.All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Motazedian, P., Quinn, N., Wells, G.A. et al. Efficacy of stellate ganglion block in treatment of electrical storm: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 14, 24719 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76663-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76663-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The lack of evidence-based management in electrical storm: a scoping review

BMC Cardiovascular Disorders (2025)