Abstract

Although various walking training robots have been developed and their effectiveness has been recognised, operating these robots requires the implementation of safety measures to avoid the risk of falling. This study aimed to confirm whether arm swing rhythm training in the sitting position using an arm swing rhythm-assisted robot, WMR, improved subsequent walking. Healthy older adults (N = 20) performed arm swing rhythm training in a sitting position for 1 min \(\times\) three times while being presented with tactile stimulation synchronised with the arm swing rhythm from a robot. An increase in walking performance was observed with increases in stride length and speed. In addition, the stabilisation of the gait pattern was observed, with a decrease in the proportion of the double-foot support phase and an increase in the proportion of the swing phase in one gait cycle. These results suggest that arm swing rhythm training in a sitting position using WMR improves gait in older adults. This will lead to the realisation of safe and low-cost robot-based walking training in sitting position.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The decline in walking ability due to aging or disease significantly reduces quality of life. Therefore, many walking training robots have been developed to maintain or improve the walking ability1,2,3,4,5,6. Most of these are power-assisted robots that use actuators to lift the lower limbs while walking. Such power-assisted robots have been confirmed to improve the gait of people whose walking ability have decreased owing to various factors, including healthy older adults, and patients with stroke and Parkinson’s disease. However, walking with assistance from a robot poses the risk of falling. Therefore, in the actual use of robots, it is necessary to secure safety personnel to prevent falls and/or use other equipment such as load release devices, which makes the robot system huge and complex. This increases the operational cost of walking training using robots. To overcome this problem, this study proposed gait training in a sitting position using the WALK-MATE ROBOT (WMR)7,8, a robot we developed to improve gait by assisting the arm swing rhythm while walking.

WMR was developed by focusing on the role of rhythm synchronisation and arm swinging in walking. First, walking synchronised with auditory rhythmic cues (RAS) improves the gait of older adults and patients with neurological disorders9,10. For example, walking while listening to a metronomic sound at a constant tempo adjusts the walking rhythm and increases the walking speed and stride length. Miyake et al. developed an interactive auditory stimulation system called the WALK-MATE system, which presents auditory cues synchronised with a person’s gait11,12,13,14. For example, interactive auditory stimulation reduces asymmetry in patients with gait dysfunction or stroke12. Hove et al. investigated the effect of interactive auditory stimulation on the patients with PD from the viewpoint of fractal scaling of stride time15. The distribution of stride times in healthy walking is not random, but includes a 1/f structure, which is a fractal-like long-term correlation16. The low fractal scaling of stride times in the gait of older people17 and PD18 patients could increase the risk of falling17. Hove et al. revealed that the WALK-MATE system improved the 1/f structure of stride times in the gate of patients with PD, but the RAS did not15. Second, proper arm swing is essential for a healthy gait19 because it strongly affects the driving legs during gait20,21. Previous studies revealed that periodic arm movements increased the muscle activity of the lower limbs during gait via interlimb coordination20,22,23,24,25 and strengthening of the arm swing led to an increased step length and walking speed26. Additionally, arm swinging is related to centre-of-mass movement reduction, torso rotational stability, and reduced energy expenditure during walking19,27,28,29. Furthermore, arm swinging enhances the coordination between the shoulder and hip motion, increasing the step length30.

Based on the effectiveness of the synchronised rhythmic stimuli and arm swing in gait training, the WMR presents tactile stimuli synchronised with the arm swing rhythm on the upper arms7,8. When walking while receiving synchronised tactile stimuli from a WMR, the hip swing angle of healthy older people increased7. Kishi et al. revealed that the rhythmic assistance of WMR increased the stride length and velocity and decreased the variability of stride time in the gait of patients with PD increased by the rhythmic assistance of WMR8. Further, these effects continued even when walking after the patients removed the WMR, which showed the after effects of synchronised tactile stimuli on the upper limbs on gait. Recently, Noghani et al. demonstrated that vibrotactile stimulation applied to the upper arm in synchronization with arm and leg swings during gait reduced stride time variability among young healthy adults31. These findings suggest that synchronised rhythmic tactile stimuli to the upper arms can improve gait patterns.

Since the WMR exhibits rhythmic tactile stimulation, they use a motor with a smaller torque than power-assisted robots7,8. Although this method has a lower risk of falling than the direct application of torque to the legs, safety measures are necessary for walking while wearing the robot. Thus, this study proposed gait training in which people first train their arm swing rhythm in the sitting position using the WMR, resulting in improved gait after removing the WMR. The rhythmic muscle activation of the limbs in arm and leg swings during walking is controlled by neural networks in the spine called central pattern generators (CPGs) with instructions from the central nervous system32,33. Arm and leg swings are controlled by different CPGs (cervical and lumbar generators, respectively), and coordination between the upper and lower limbs is achieved through the mutual connection of these CPGs, through which the arm swing is considered to affect leg movement during gait32,33,34,35. Additionally, using EMG measurements, Klimstra et al. found the same basic rhythmic pattern in arm movement when swinging arms while walking and when swinging arms, suggesting that the same neural mechanisms could be involved in arm swinging in both cases34. Therefore, we assumed that by training the arm swing rhythm with the WMR while sitting, it would be possible to improve subsequent gait. The purpose of this study was to investigate whether arm swing rhythm training using WMR in the sitting position improves the gait of elderly people.

Results

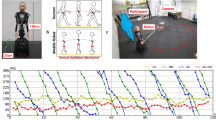

Twenty healthy older adults participated in this experiment. The training procedure was as follows. First, the participants walked twice along a flat 50 m corridor. After a short break, they walked along the corridor again to measure their gait performance and pattern at baseline (precondition). Subsequently, they wore the WMR (Fig. 1) and carried out the training arm-swing rhythm with the robot in a sitting position for one minute. After training, they removed the robot and walked along the corridor to measure their gait performance and patterns. The process was repeated three times (Post1, Post2, and Post3).

WALK-MATE ROBOT consisted of three modules: control, actuator, and power. The control module synchronised the robot’s rhythm to the human’s arm-swing rhythm using the arm-swing angular measured by the encoders. The actuator module presented the rhythmic tactile stimuli on the left and right upper arms of the participants based on the robot rhythm synchronised to the arm-swing rhythm. The power module included the battery. The participants trained their arm-swing rhythm using WMR in the sitting position. The robot presented the rhythmic tactile stimuli while the participants swung their left and right arms backwards.

We measured stride length, stride speed, and stride period, which are indicators of gait performance, as indicators of gait improvement by training the arm swing rhythm in the sitting position. The gait performance of older adults is lower than that of young people36,37,38,39,40,41. Older adults’ gait is characterised by a shorter stride length, lower speed, and lower cadence36. Additionally, the ratio of the time of the double-foot support and swing phases to one gait cycle was measured. The ratio of the swing and stance phases to one gait cycle is an index of gait stability42,43,44,45. In the swing phase, the forward movement of the lower limbs occurs, while the foot support phase maintains the stability and forward progression of the trunk and lower limbs. Older people with poor elasticity and stiff spines walk cautiously to remain stable, during which the foot support phase increases and the swing phase decreases46,47.

Gait performance

Table 1 and Fig. 2 shows the results of gait performance. As seen in Fig. 2A, the average stride length increased after the training. The mean stride lengths in the Post1, Post2, and Post3 conditions were significantly larger than those in the Pre-condition (\(p=0.018\), \(p<0.001\), and \(p=0.011\), respectively). Additionally, the stride length in the Post2 and Post3 conditions was significantly larger than that at Post1 condition (\(p<0.001\) and \(p=0.016\), respectively). However, there was no significant difference between the Post2 and Post3 conditions (\(p=0.812\)). Thus, the stride length continued to increase from the pre-condition to the Post2 condition. The rate of increase in the average stride length from the Pre condition to the Post3 condition was 6.8%.

Figure 2B shows the results for stride speed. In addition to the stride length, the stride speed seemed to increase from the Pre condition to Post2 condition. Although there was no significant difference between the pre- and Post1 conditions (\(p=0,126\)), the stride speeds in the Post2 and Post3 conditions were higher than those in the Pre condition (\(p<0.001\) and \(p=0.006\), respectively). Furthermore, the stride speeds at Post2 and Post3 were higher than that at Post1 (\(p<0.001\) and \(p=0.005\), respectively). However, we did not find a significant difference for the stride speed between the Post2 and Post 3 (\(p=0.812\)). Therefore, stride speed increased under the Post2 and Post3 conditions compared to the Pre and Post1 conditions. The average stride speed increased by 4.9% from the Pre condition to the Post3 condition.

The results of the stride period are shown in Fig. 2C. We found no significant differences in the stride period among any of the conditions. The p values between the Pre- and Post1 to Post3 conditions were 0.570, 0.144, and 0.179, respectively. The values between the Post1 and Post2 conditions and the Post1 and Post3 conditions were 0.179 and 0.215, respectively. The p value between the Post2 and Post3 conditions was 0.622.

Gait pattern

Table 1 and Fig. 3 shows the results of the gait pattern. The ratio of the double foot support time (Fig. 3A) at the Post2 condition was significantly smaller than those at the Pre- and Post1 conditions (\(p=0.019\) and \(p=0.004\), respectively). Thus, the double support time in one gait cycle was relatively shortened after two training sessions using the WMR in the sitting position. However, there were no significant differences between the Pre- and Post1/Post3 conditions (\(p=0.799\) and \(p=0.053\), respectively), or between the Post1/Post2 and Post3 conditions (\(p=0.102\) and \(p=0.598\), respectively).

The ratio of the swing phase in the left leg (Fig. 3B) was significantly different between the Pre- and Post2/Post3 conditions (\(p=0.045\) and \(p=0.045\), respectively). The ratio of the swing phase in the right leg (Fig. 3C) was significantly different between the Post1 and Post2 conditions (\(p=0.029\)). These results suggest that the participants swung their legs for a longer period within one gait cycle after than before the training. No significant differences were observed between the other conditions. For the left leg, the p values between the Pre- and Post1, Post1 and Post2/Post3, and Post2 and Post3 conditions were 0.605, 0.104, 0.059, and 0.841, respectively. For the right leg, the values between the Pre and Post1/Post2/Post3, between the Post1 and Post3, and between the Post2 and Post3 conditions were 0.841, 0.165, 0.165, 0.165, and 0.841, respectively.

Results of gait patterns for each condition. (A) The ratio of the double support phase. (B) The ratio of the swing phase of the left leg. (C) The ratio of the swing phase of the right leg. * and ** depict \(p<0.05\) and \(p<0.01\), respectively. The error bars show the standard deviations between the participants.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether arm swing rhythm training in a sitting position using the WMR improves subsequent gait in healthy older adults. The participants performed one minute of seated training with the WMR three times. Increases in stride length and velocity were observed after the sitting training. Additionally, a decrease in the proportion of the double-foot support phase and an increase in the proportion of the swing phase in a single cycle were observed. These results indicate that seated arm swing training with WMR improves subsequent gait performance and patterns.

In the gait of healthy individuals, the left and right swing phases occupy 40 % of the gait cycle48 and the double-foot support time occupies 20 % of the gait cycle49. Because of the multiple declines in physiological body functions, aging shortens and lengthens the swing phase and foot support phase, respectively, to maintain gait stability compared with healthy younger people38,50. At baseline, our older individuals showed a shorter swing phase and longer double-foot support phase than in healthy people. After seated training with the WMR, the ratios of the left and right swing phases increased while the proportion of the double foot support phase decreased. Thus, the ratio of the swing phase to the double foot support phase approached the average of healthy people by training the arm swing rhythm with the WMR in the sitting position.

With improvements in gait performance, stride length and stride speed improved from baseline by seated training of the arm-swing rhythm with the WMR. These improvements were observed from Post1 to Post2. However, the stride period showed no significant differences between the Pre- and Post1 conditions. Previous studies have reported that the change in stride speed is influenced mainly by the stride length rather than the stride period51. The preferred walking speed of healthy older adults in their seventh decade declines by 1 % per year, owing to a decrease in stride length rather than cadence. Thus, the participants in this study had increased stride speeds that decreased with age by increasing the stride length without changing the stride period.

The stride length, stride velocity, rate of double-feet support phase, and rate of swing phase improved from baseline by seated training using the WRM, some of which improved from the Post1 condition to the Post2 condition, but no significant differences were observed between the Post2 and Post3 conditions. The ceiling effect could be one reason why no differences were observed between conditions. By training using the robot, the left and right swing phase ratios and the double-foot support phase increased, which is the average for healthy participants48,49. These results suggest that arm swing rhythm training in a sitting position with the robot had a sufficient effect on improving the gait of the participants. However, another reason could be that the fatigue caused by training and gait measurements offset the improvement effect. Considering that the average stride length of adults is approximately 1.40 m/s52, there would still be room for improvement in the average stride length of in the Post2 and Post3 conditions. Although we provided breaks during the experiment, and the participants were free to take as many breaks as they wanted, fatigue from training and gait measurement may still have created this margin. In future studies, the appropriate training duration and frequency in the sitting position should be investigated.

This study hypothesised that arm swing rhythm training in the sitting position would improve arm swing rhythm in subsequent walking and that gait would be improved through the interaction of CPGs for the upper and lower limbs. The CPG controls the upper and lower limbs separately and generates the overall walking rhythm via coordination of the four limbs34,35. Additionally, upper-limb movement during gait affects lower-limb movement, contributing to the stabilisation of walking20,22,23,24,25,26. Furthermore, the CPG receives muscle activity programs from the central nervous system (CNS)53 and returns feedback to the CNS through somatosensation, thereby generating a walking rhythm in cooperation with the CNS34. Tactile stimulation by the WMR could mediate this coordination between CPG and the CNS and influence gait after sitting training of the arm swing rhythm. The coordinated movement of the leg and arm cycles during gait follows a 1:1 correspondence, maintaining a certain phase relationship for healthy gait28,54,55. For instance, backward arm swings contribute to the activation of the soleus muscles for leg swinging19. Thus, seated rhythmic arm swing training with WMR could have modified the initiation timing and duration of the backward arm swing. This potentially increases the swing phase duration and decreases the double leg support phase duration during walking.

However, this study did not directly confirm this hypothesis. In the future, the mechanism of gait improvement by seated training of the arm swing rhythm using WMR should be investigated. First, it is necessary to clarify how arm swing changes with training during sitting and subsequent walking activities. Additionally, to realise effective seated training using the WMR, it is important to clarify how the changed arm swing improves the movement of the legs and whole body during walking through interlimb coordination. Furthermore, it is important to clarify how CPG is involved in improving gait using seated training with the WMR. This could be explored by measuring the muscle activity patterns using electromyography (EMG). An important function of the CPG is to generate cooperative activity patterns of the corresponding muscles for walking56, which can be estimated by measuring the spatiotemporal patterns of multiple muscle activities using EMG and synergy analysis57,58. The measurement of arm muscle activity patterns during arm swinging in a sitting position, as well as upper and lower limb muscle activity patterns during subsequent walking, will help clarify the mechanism by which arm swing rhythm training in a sitting position using WMR improves gait. Further, it is a limitation of this study that we only compared gait before and after sitting training using the WMR. Studies should be conducted with an appropriate control group, such as arm-waving training in a sitting position without a robot, or walking training with a regular therapist.

Conclusions

This study aimed to clarify whether arm swing rhythm training in a sitting position using WMR, which presents synchronised rhythms to the upper limbs, improves subsequent gait. By seated training for 1 min \(\times\) three times, walking performance was improved by increasing the stride length and stride speed. Additionally, an improvement in the gait pattern was observed with a decrease in the proportion of the double-foot support phases and an increase in the proportion of the swing phase in one gait cycle. These results suggest that arm swing rhythm training in a sitting position using the WMR leads to improvement in gait. This will lead to the establishment of a safe and low-cost walking training method that uses robots in a sitting position.

Methods

Participants

Twenty healthy older adults (10 females and 10 males) were recruited. The participants received renumeration for their participation in the study. The average and standard deviation of the ages were \(78.5 \pm 7.5\) years. Their height and weight were \(163 \pm 18\) cm and \(59.5 \pm 20.5\) kg, respectively. None of them currently suffered from severe injuries or had a medical history that significantly affected their gait. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Tokyo Institute of Technology and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

WALK-MATE ROBOT

Hardware

The WMR (WALK-MATE LAB Co., Ltd., Japan) is a wearable device equipped with actuator, control, and power modules, which weighed 4.6 kg8 (Fig. 1). The actuator module comprises two motors (DC brushless motors, DR-4316-X14B00421, ShinanoKenshi, Nagano, Japan) mounted on the left and right shoulder boxes and connected to frames. The motor torque for presenting the tactile rhythmic stimuli was 1.17 Nm, which was not sufficiently large to move the participant’s arms. One end of the frame was connected to a motor, whereas the other end was connected to a band around the arm of the person. The motor drove the frame to rotate, thereby providing a rhythmic stimulus to the participant’s arms. The control module consists of a microcomputer and two encoders. The microcomputer was equipped with a box placed on the back of the robot to generate the robot rhythm and motor-driving commands. Encoders are mounted on the left and right motors to measure the swing angles of the arm. The measurement range was \(\pm 150\)\(^{\circ }\), the measurement resolution was 1.2 \(^{\circ }\), and the sampling rate was 100 Hz. The power module includes a battery mounted on the backbox.

Algorithm for synchronisation and presentation of the rhythmic stimuli

To synchronise the robot rhythm with the arm swing rhythm and present the tactile stimuli, we used the oscillator entrainment model proposed in our previous studies7,8 based on the Walk-Mate Model11, which represented the rhythms of the robot and human as phase oscillators. This model consists of mutual synchronisation and phase-difference control modules. Using the mutual synchronisation module, the robot synchronised its rhythm with the arm-swing rhythm. The mutual synchronisation model is determined as follows:

where \(\theta _{m\_l}\) and \(\theta _{m\_r}\) denote the left and right motor phases of the robot, respectively. \(\theta _{h\_l}\) and \(\theta _{h\_r}\) represent the left and right human phases of the arm swing measured by the left and right encoders, respectively. \(\omega _{m\_l}\) and \(\omega _{m\_r}\) represent the robot’s left and right angular frequencies, respectively. \(k_{hm}\) and \(k_{m\_rl}\) are the coupling strength constants between the human and robot phases, and between the left and right phases of the robot. We set \(k_{hm} = 0.25\) and \(k_{m\_rl} = 2.5\) based on our previous study8. From the second term on the right side of equations 1 and 2, the robot was able to synchronise its left and right rhythms with the left and right rhythms of the human arm swing. By the third term on the right side, the robot synchronises its left and right rhythms to balance the rhythms of the human’s left and right arm swings.

The phase-difference control module matches the left and right angular frequencies of the robot, \(\omega _{m\_l}\) and \(\omega _{m\_r}\), respectively, to those of the human arm swing. The differentials of \(\omega _{m\_l}\) and \(\omega _{m\_r}\) were as follows:

where \(\Delta \theta _d\) is the predetermined target value of the phase difference between the robot and human. When \(\Delta \theta _{d}\) is zero, the robot perfectly controls its own frequency relative to that of the human. \(\mu\) is the gain that matches the robot’s frequency with that of the human’s frequency using the difference between them. In this study, we set \(\mu = 0.08\) and \(\Delta \theta _d = 0\) to the same values as in our previous study8.

We determined the timing and duration of the motor drive by using \(\theta _{m\_l}\) and \(\theta _{m\_r}\). If \(\alpha< \theta _{m\_l} < \alpha + \beta\), then the robot drives the left motor. \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) indicate the starting phase (timing) and duration of motor driving, respectively. If \(\pi + \alpha< \theta _{m\_r} < \pi + \alpha + \beta\), the robot drives the right motor. We set \(\alpha = 1.3\pi\) and \(\beta = 0.6\pi\) based on our previous study8. In this case, the robot presented tactile stimuli to the participant’s upper arms when they swung their arms backward.

Task and conditions

The task involved swinging the arms for one minute in a sitting position while receiving rhythmic tactile stimuli from the upper arms of the robot. The participants performed the training thrice. After each training session, the participants walked 50 m along a flat corridor to measure their gait under the Post1, Post2, and Post3 conditions. Before training, the participants walked the corridor to measure their baseline gait (pre-condition).

Procedures

First, the participants wore sensors to measure their gait. The sensors were worn throughout the experiment. Before the pre-condition, the participants walked 50 m along the corridor twice as a warm-up. After a break of at least two minutes while sitting on a chair, they walked along the corridor again to measure the baseline (pre-condition). Subsequently, we repeated the following procedure three times for the Post1, 2, and 3 conditions. First, an experimenter placed the robot on the participants, while they remained seated. The participants then trained their arm swing rhythm with the robot in the sitting position. After the participants removed the robot, a break of at least two minutes was provided. Finally, the participants walked 50 m to measure their gait. Participants were instructed to initiate arm swinging with their arms hanging naturally at their sides, while limiting excessive elbow bending. This approach intended to minimize fatigue from excessive effort and simulate normal gait. Moreover, the participants were asked to swing their arms, while being aware of the tactile stimuli, and were cautioned against exaggerated arm movements. Regarding arm swing speed, participants were advised to swing their arms slightly faster than they normally would when walking. Previous research has demonstrated the effectiveness of metronome-based walking training using slightly faster tempos10. With the assistance of an experimenter, participants were able to don and doff the robot in under a minute. This rapid turnaround suggests that the time spent on these tasks did not confound the assessment of the training effect. Participants were able to take breaks whenever they wished. The total experiment time was approximately one hour.

Gait measurement and statistical methods

To evaluate the gait of the participants, we used a wearable system for gait measurement, the WALK-MATE GAIT CHECKER (WALK-MATE LAB Co., ltd., Japan). This system estimates the 3D foot trajectory and duration of the gait phase, such as the swing and stance phases, using two IMUs (AMWS020, ATR-Promotions, Japan) attached to the left and right ankles with special belts. The size and weight of the IMU were 37 \(\times\) 46 \(\times\) 12 mm and 22 g, respectively. Spatiotemporal gait parameters were estimated as previously described59. The system utilized sagittal plane angular velocity data obtained using a gyro sensor to detect toe-off and heel-strike events, characterized by significant changes in angular velocity. Subsequently, the 3-D foot trajectory of each step was calculated using the acceleration data obtained using the accelerometer. Using this wearable system, we measured the stride length, speed, and period for gait performance and the double support phase and swing phase for gait pattern.

For the statistical analysis, we removed the first and last steps. Thirty steps (15 right, 15 left) from the middle of the dataset of each walking trial were used in analyses. To analyse the average of each index, we used the Wilcoxon signed-rank test with multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) method, which was performed using R (version 4.2.3). The significance level was set at 0.05, and all p values reported in this manuscript were adjusted using the BH method.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analysed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Gavrila Laic, R. et al. A state-of-the-art of exoskeletons in line with the who’s vision on healthy aging: From rehabilitation of intrinsic capacities to augmentation of functional abilities. Sensors 24, 2230. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24072230 (2024).

Rodríguez-Fernández, A., Lobo-Prat, J. & Font-Llagunes, J. Systematic review on wearable lower-limb exoskeletons for gait training in neuromuscular impairments. Journal of Neuroengineering and Rehabilitation 18, 1–21 (2021).

Moucheboeuf, G. et al. Effects of robotic gait training after stroke: A meta-analysis. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 63, 518–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2020.02.008 (2020).

Yang, J. et al. Effect of exoskeleton robot-assisted training on gait function in chronic stroke survivors: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open 13, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-074481 (2023).

Chen, S., Zhang, W., Wang, D. & Chen, Z. Effects of robotic gait training after stroke: A meta-analysis. European Journal of physical and rehabilitation Medicine 6-, 1–19, https://doi.org/10.23736/S1973-9087.24.08354-0 (2024).

Xue, X., Yang, X. & Deng, Z. Efficacy of rehabilitation robot-assisted gait training on lower extremity dyskinesia in patients with Psarkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews 85, 101837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2022.101837 (2023).

Yap, R. & et al. Gait-assist wearable robot using interactive rhythmic stimulation to the upper limbs. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 6 (2019).

Kishi, T. & et al. Synchronized tactile stimulation on upper limbs using a wearable robot for gait assistance in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 7 (2020).

Thaut, M. H. & Abiru, M. Rhythmic auditory stimulation in rehabilitation of movement disorders: A review of current research. Music Perception 27, 263–269 (2010).

Ghai, S., Ghai, I. & Effenberg, A. O. Effect of rhythmic auditory cueing on aging gait: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging and Disease 9, 901–923. https://doi.org/10.14336/AD.2017.1031 (2018).

Miyake, Y. Interpersonal synchronization of body motion and the wlakmate walking support robot. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 25, 638–644 (2009).

Muto, T., Herzberger, B., Hermsdoerfer, J., Miyake, Y. & Poeppel, E. Interactive cueing with walk-mate for hemiparetic stroke rehabilitation. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation 9, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-0003-9-58 (2012).

Uchitomi, H. et al. Interactive rhythmic cue facilitates gait relearning in patients with parkinson’s disease. PloS One 8, e72176 (2013).

Uchitomi, H. et al. Effect of interpersonal interaction on festinating gait rehabilitation in patients with parkinson’s disease. Plos one 11, e0155540 (2016).

Hove, M. et al. Interactive rhythmic auditory stimulation reinstates natural 1/f timing in gait of parkinson’s patients. PloS one 7, e32600 (2012).

Hausdorff, J. et al. Fractal dynamics of human gait: stability of long-range correlations in stride interval fluctuations. Journal of Applied Physiology 80, 1448–1457 (1996).

Herman, T. et al. Gait instability and fractal dynamics of older adults with a “cautious” gait: why do certain older adults walk fearfully?. Gait & Posture 21, 178–185 (2005).

Hausdorff, J. Gait dynamics in Parkinson’s disease: common and distinct behavior among stride length, gait variability, and fractal-like scaling. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science 19 (2009).

Meyns, P., Bruijn, S. & Duysens, J. The how and why of arm swing during human walking. Gait & Posture 38, 555–562 (2013).

Weersink, J. et al. Time-dependent directional intermuscular coherence analysis reveals that forward and backward arm swing equally drive the upper leg muscles during gait initiation. Gait & Posture 92, 290–293 (2022).

Weersink, J. et al. Intermuscular coherence analysis in older adults reveals that gait-related arm swing drives lower limb muscles via subcortical and cortical pathways. The Journal of Physiology 599, 2283–2298 (2021).

Ferris, D., Huang, H. & Kao, P. Moving the arms to activate the legs. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews 34, 113–120 (2006).

Huang, H. & Ferris, D. Upper and lower limb muscle activation is bidirectionally and ipsilaterally coupled. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 41, 1778–1789 (2009).

Hill, A. & Nantel, J. The effects of arm swing amplitude and lower-limb asymmetry on gait stability. PLoS One 14, e0218644 (2019).

Nakakubo, S. et al. Does arm swing emphasized deliberately increase the trunk stability during walking in the elderly adults?. Gait & Posture 40, 516–520 (2014).

Weersink, J. & et al. Enhanced arm swing improves parkinsonian gait with eeg power modulations resembling healthy gait. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 91, 96–101 (2021).

Zehr, E. & Duysens, J. Regulation of arm and leg movement during human locomotion. The Neuroscientist 10, 347–361 (2004).

Hejrati, B., Merryweather, A. & Abbott, J. Generating arm-swing trajectories in real-time using a data-driven model for gait rehabilitation with self-selected speed. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 26, 115–124 (2017).

Thomas, S., Vega, D. & Arellano, C. Do humans exploit the metabolic and mechanical benefits of arm swing across slow to fast walking speeds?. Journal of Biomechanics 115, 110181 (2021).

Ustinova, K., Langenderfer, J. & Balendra, N. Enhanced arm swing alters interlimb coordination during overground walking in individuals with traumatic brain injury. Human Movement Science 52, 45–54 (2017).

Noghani, M. A., Hossain, M. T. & Hejrati, B. Modulation of arm swing frequency and gait using rhythmic tactile feedback. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 31, 1542–1553. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2023.3249628 (2023).

Klarner, T. & Zehr, E. P. Sherlock holmes and the curious case of the human locomotor central pattern generator. Journal of Neurophysiology 120, 53–77. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00554.2017 (2018).

Yang, J., Jaynie, F. & Gorassini, M. Spinal and brain control of human walking: implications for retraining of walking. The Neuroscientist 12, 379–389 (2006).

Klimstra, M. & et al. Neuromechanical considerations for incorporating rhythmic arm movement in the rehabilitation of walking. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science 19 (2009).

Dzeladini, F., Kieboom, J. V. D. & Ijspeert, A. The contribution of a central pattern generator in a reflex-based neuromuscular model. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 8, 371 (2014).

Osoba, M. & et al. Balance and gait in the elderly: A contemporary review. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology 4, 143–153 (2019).

Jahn, K., Zwergal, A. & Schniepp, R. Gait disturbances in old age: classification, diagnosis, and treatment from a neurological perspective. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International 107, 306 (2010).

Danoudis, M., Ganesvaran, G. & Iansek, R. Disturbances of automatic gait control mechanisms in higher level gait disorder. Gait & Posture 48, 47–51 (2016).

Menz, H., Lord, S. & Fitzpatrick, R. Age-related differences in walking stability. Age and ageing 32, 137–142 (2003).

Verlinden, V. et al. Gait patterns in a community-dwelling population aged 50 years and older. Gait & Posture 37, 500–505 (2013).

Hausdorff, J., Rios, D. & Edelberg, H. Gait variability and fall risk in community-living older adults: a 1-year prospective study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 82, 1050–1056 (2001).

Makino, K. et al. Fear of falling and gait parameters in older adults with and without fall history. Geriatrics & Gerontology International 17, 2455–2459. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13102 (2017).

Donatoni da Silva, L., Shiel, A., Sheahan, J. & McIntosh, C. Six weeks of pilates improved functional mobility, postural balance and spatiotemporal parameters of gait to decrease the risk of falls in healthy older adults. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 29, 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2021.06.014 (2022).

Soulard, J., Vaillant, J., Baillet, A., Gaudin, P. & Vuillerme, N. Gait and axial spondyloarthritis: Comparative gait analysis study using foot-worn inertial sensors. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 9, e27087. https://doi.org/10.2196/27087 (2021).

Figueiredo, P. & et al. Assessment of gait in toddlers with normal motor development and in hemiplegic children with mild motor impairment: a validity study. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy 17, 359–366 (2013).

Murray, M., Kory, R. & Clarkson, B. Walking patterns in healthy old men. Journal of Gerontology 24, 169–178 (1969).

Murray, M. Walking patterns of normal women. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 51, 637–650 (1970).

Loudon, J. K., Swift, M. & Bell, S. The clinical orthopedic assessment guide (Human Kinetics, 2008).

Webster, J. & Darter, B. Principles of normal and pathologic gait. In Webster, J. B. & Murphy, D. P. (eds.) Atlas of Orthoses and Assistive Devices, 49–62, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-48323-0.00004-4 (Elsevier, 2019).

Taylor, M. & et al. Gait parameter risk factors for falls under simple and dual task conditions in cognitively impaired older people. Gait & Posture 37, 126–130 (2013).

Pirker, W. & Katzenschlager, R. Gait disorders in adults and the elderly: A clinical guide. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift 129, 81–5 (2017).

Ostrosky, K. & et al. A comparison of gait characteristics in young and old subjects. Physical Therapy 74, 637–644 (1994).

Takakusaki, K., Habaguchi, T., Ohtinata-Sugimoto, J., Saitoh, K. & Sakamoto, T. Basal ganglia efferents to the brainstem centers controlling postural muscle tone and locomotion: a new concept for understanding motor disorders in basal ganglia dysfunction. Neuroscience 119, 1, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00095-2 (2003).

Ford, M. P., Wagenaar, R. C. & Newell, K. M. Arm constraint and walking in healthy adults. Gait & Posture 26, 135–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2006.08.008 (2007).

Hejrati, B., Chesebrough, S., Bo Foreman, K., Abbott, J. J. & Merryweather, A. S. Comprehensive quantitative investigation of arm swing during walking at various speed and surface slope conditions. Human Movement Science 49, 104–115, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2016.06.001 (2016).

Rybak, I. A., Shevtsova, N. A., Lafreniere-Roula, M. & McCrea, D. A. Modelling spinal circuitry involved in locomotor pattern generation: insights from deletions during fictive locomotion. The Journal of Physiology 577, 617–639. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2006.118703 (2006).

Dominici, N. & et al. Locomotor primitives in newborn babies and their development. Science 334, 997–999 (2011).

Aoi, S. & Funato, T. Neuromusculoskeletal models based on the muscle synergy hypothesis for the investigation of adaptive motor control in locomotion via sensory-motor coordination. Neuroscience Research 104, 88–95, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neures.2015.11.005 (2016). Body representation in the brain.

Mao, Y. & et al. Estimation of stride-by-stride spatial gait parameters using inertial measurement unit attached to the shank with inverted pendulum model. Scientific Reports 11, 1391 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI; Grant Numbers: JP24K00844.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.O., B.W., and Y.M. designed the study. T.O., B.W., and R.Y. designed and conducted the experiments. T.O., B.W., and R.Y. analysed the results. T.O. wrote the manuscript. All the authors interpreted the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

T.O., B.W., and R.Y. declare no competing interests. Y.M. is remunerated as a director of WALK-MATE LAB Co., Ltd. and holds shares in the company.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ogata, T., Wen, B., Ye, R. et al. Gait Training of Healthy Older Adults in a Sitting Position using the Wearable Robot to Assist Arm-swing Rhythm, WALK-MATE ROBOT. Sci Rep 14, 24833 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76676-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76676-4