Abstract

As a critical component of a welded structure, the integrity of the welded joint significantly affects the safety and reliability of the structure in service. Therefore, it is essential to investigate the integrity of welded joints. However, given the harshness of standard measurements renders them unsuitable for application to small volume zones, welded structures or in-service structures. In this study, the fracture properties of a Q235 steel butt-welded joint was evaluated by boundary effect modelling (BEM) method and the ball indentation (BI) method. The results demonstrate that the fracture toughness distribution obtained by the two methods are consistent, with the highest fracture toughness in the weld metal, followed by the heat-affected zone and the base metal, and the lowest fracture toughness in the fusion zone, which is in agreement with the results of the metallographic testing. Furthermore, the relative errors of the zones obtained by the ball indentation method and the boundary effect modelling method ranging from 10.16 to 19.05%, which indicates safety margin ought to be considered for employing the BI method to determine fracture properties of in-service structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Welding technology plays a significant role in the field of engineering machinery, including aircraft, automobiles, and shipbuilding1. Welded joints represent a significant challenge to the development of safety and reliability in engineering machinery structures2. A welded joints comprise four primary zones: weld metal (WM), fusion zone (FZ), heat-affected zone (HAZ), and base metal (BM). Variations in chemical composition and welding temperature across these zones lead to anisotropy and heterogeneity within the joint3,4. Furthermore, various macro- and micro- defects in the welded joint gives rise to further concerns5,6,7,8, contributing to the inconsistent mechanical properties observed in welded joints9. Besides, the fracture behavior of welded joint exhibits a mixed ductile-brittle fracture mechanism, as evidenced by studies10,11. The inherent characteristics of welded joint render them a vulnerable part in engineering structures, thus limiting the application and development of engineering.

For the sake of design and integrity assessment of the fracture toughness of engineering machinery, it is necessary to conduct a precise investigation of welded joint. At present, the fracture properties testing of welded joint is primarily based on J integral, crack tip opening displacement (CTOD) and linear elastic fracture mechanics (LEFM)12,13,14,15. Among the fracture toughness testing methods, resistance curve tests such as the single edge notch bend (SENB) test and compact tensile (CT) test have experienced considerable development and many countries and institutions have issued guidelines for ductile metal materials13,14,15, which can be used to determine the critical fracture toughness JIC, CTOD and KIC. Nevertheless, it is possible that many welded structures and small specimens may not be able to meet the specimen size requirements specified by standards. For example, if the specimen is too small, the internal LEFM region does not exist, and the entire specimen is subject to the combined effects of the front and back specimen boundaries. In addition, there is a practical issue associated with the early detection of short fatigue cracks, i.e., the need to estimate the elastic and plastic fracture loads of a metallic structure that exhibits a short fatigue crack, even though the conditions of the LEFM or American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) standards are not met. Besides, standard fracture toughness testing of narrow localized areas of welded joints (e.g. heat affected zone) is difficult to achieve due to sample size limitations. Consequently, the development of concise and efficient fracture toughness testing methods holds great theoretical significance for engineering.

Regarding structural integrity assessment methods, the boundary effects model (BEM)16,17,18,19 has been popularized and used in structural integrity assessment. With the model, there is no requirement that the dimensions of the specimen must conform to the strict specifications in force, e.g., height, thickness, initial crack length, and so forth. Additionally, the initial crack need not be a preformed fatigue crack. It can be underlined that the boundary effect model has great potential for investigating the fracture mechanisms of metallic materials20,21,22,23. Alternatively, as a micro-sample testing technique that has been extensively investigated in recent years, the ball indentation method is relatively simple in its testing procedure and specimen preparation24,25. The test can be executed by taking small specimens or no sampling to realize the performance testing in the position determination area or in the area where it is not feasible to take samples for measurement. The ball indentation test has minimal damage to the measurement surface of the specimen and is convenient for testing the mechanical properties of welded zones, pressure vessels or in-service equipment in actual engineering, thus offering a promising avenue for engineering applications26.

In terms of the investigation of fracture toughness in welded joints, Zhang27 and Li28 examined the fracture properties of Q235 and Q345 weld seam by the CTOD test and Charpy impact test, respectively Subsequently, Wang29,30 summarized these fracture toughness indices, highlighting a superior fracture toughness in the weld metal compared to the base metal. In further study, Alireza31 adopted a mesoscale modeling approach combining hardness and microstructure to describe the failure of spot welds. The results illustrated that the failure location and mechanism were influenced by the fusion boundary. While previous studies predominantly focused on specific zones, a few have comprehensively evaluated the fracture toughness across weld metal, fusion zone, heat-affected zone, and base metal. Nevertheless, the fracture mechanism of different zones within welded joints remains a compelling research area, driving the investigation outlined in this paper. Nevertheless, it is challenging to ascertain the applicability of previous work to welded joint, given that researchers have concentrated solely on homogeneous and uniformly distributed materials when developing fracture toughness assessment methodologies. In brief, standard measurements of fracture toughness are less suitable for usage in small volume zones, welded structures, or in-service engineering structures due to their inherent cumbersomeness. In this study, a destructive notched three-point bending (3-p-b) test and non-destructive ball indentation test were performed on distinct zones of Q235 steel welded joint, and the integrity assessment of the welded joint was investigated. Alternatively, the adaptability and accuracy of these two methods in predicting the fracture properties of welded joint were explored. Finally, metallographic inspection of the welded joint was carried out to characterize the microstructure of the various zones of the welded joint, and to uncover the distribution of the fracture toughness of the welded joint.

Evaluation of the fracture toughness of butt-welded joint using the boundary effect model

Brief of boundary effect modelling with plastic zone at crack tip

In a type I mode fracture test of a 3-p-b notched specimen (see Fig. 1), factors such as the initial notch\({a_0}\), the nominal stress\({\sigma _n}\), and the plastic zone \({a_p}\) of crack-tip are involved. The BEM16,17,18,19 for finite-size plates established a relationship between the nominal strength \({\sigma _n}\) and yield strength \(\sigma _{y}^{{}}\)(Eq. (1)) by The equivalent crack \({a_e}\) depends on specimen form\(\alpha\), geometry \(Y\left( \alpha \right)\), and initial notch \({a_0}\) (Eq. (2)). The characteristic crack \(a_{\infty }^{\ast}\) can be determined by Eq. (5). By accounting for the plastic zone, the relation between \({\sigma _n}\) and Py is derived through the balance equations of force and moment27,28,29, expressed as Eq. (7). The elastoplastic fracture of 3-p-b specimens can be predicted by Eq. (8), which is derived from Eqs. (1) and (5).

The nominal strength \({\sigma _n}\) can be determined using the measured yield load \({P_y}\) of each specimen as Eq. (7). The equivalent crack length \({a_e}\) can be calculated using Eqs. (2) and (3). Yield strength \(\sigma _{y}^{{}}\)and fracture toughness KIC can be determined by Eq. (8) incorporating curve fitting. As a result, a methodology for determining\(\sigma _{y}^{{}}\) and KIC of composite metal (e.g. welded joint) is developed using small notched 3-p-b specimens.

Assessment of fracture toughness of welded joints via boundary effect model

Specimen preparation

Q235 steel was selected as the base metal (BM). In this study, the E4303 electrode with a diameter of 2.5 mm was utilized as the weld metal (WM). The mechanical properties of the Q235 steel and E4303 are provided in Table 1.

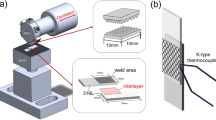

The steel plates were initially prepared according to the relevant code32, followed by joining two Q235 steel plates, each with a thickness of 20 mm, as well as two plates with a thickness of 25 mm. Shielded metal arc welding (SMAW) was performed by a skilled technician using parameters of 80 A welding current, 30 V welding voltage, and a welding speed of 5 mm/s, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The welding process was qualified in accordance with the Structural Welding Code–Steel (AWS D1.1:2020)33. Moreover, to minimize welding deformation, the welding process was conducted on a technical pad.

Different zones of a welded joint exhibit varying mechanical properties, microstructures, and respond differently to applied loads. In order to clarify the difference between the fracture properties of each zone, 3-point bend (3-p-b) specimens were extracted from the welded plates using wire cutting with a diameter of 0.8 mm34. Specimens from different zones of the welded joint are displayed in Fig. 3, with initial cracks at different locations in the butt-welded joint and a notch width is 1.5 mm. The configuration and geometric parameters for all specimens within the four zones are detailed in Table 2.

3-p-b test of the specimens

Prior to the 3-p-b test, all specimen surfaces underwent polishing to enhance the observation of the crack tip plastic zone using a digital microscope (DM) during the test. The tests were carried out under ambient temperature and pressure. A universal 100kN load testing machine was utilized for the tests as shown in Fig. 4. In displacement control mode, the crosshead of the machine applied a loading velocity of 1.5 mm/min to the upper surface of the specimen. The load-displacement curves of specimens with varying \(\alpha\)-ratios are displayed as Fig. 5.

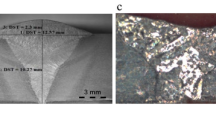

Measurement of plastic zone in front of crack tip

In practice, a plastic zone formed at the crack tip of metallic structures when the applied stress exceeds the capacity of material35,36,37,38. It is noteworthy that the crack-tip plastic zone typically exhibits a two-dimensional shape, with the width exceeding the length, as observed in the test. As presented in Fig. 6a, a dimpled is clearly visible at the crack tip, resulting from yielding deformation. The area of interest was observed through a digital microscope (DM), as depicted in Fig. 6b. A small gradation on the scale represents 0.5 mm, allowing for the estimation of the plastic zone length\({a_p}\) along the crack growth direction.

The plastic zone in different zones of the welded joint is displayed in Fig. 7. Both in the weld metal and the base metal, the plastic zone exhibits a butterfly-like shape, with yield zones typically found at the crack tip or stress concentration points. This observation aligns with findings from several studies on simulating the plastic zone in welded joints39,40,41,42. Furthermore, the maximum plastic zone size of welded joint was measured, followed by an assessment of the plastic zone length across four zones within the joint for normality using the Anderson-Darling test method43. The average plastic zone length \({a_P}\)at the crack tip for each specific zone within the welded joint is provided in Table 3.

Determination of $${\sigma _y}$$ and KIC from curve-fitting

As illustrated in Fig. 8, the fracture properties of these zones can be determined from the \(1/\sigma _{n}^{2} - {a_e}\) curves of weld metal, fusion zone, heat-affected zone, and base metal.

As shown in Table 4, the fracture toughness KIC of the weld metal surpassed that of the heat-affected zone, the base metal, and the fusion zone, in descending order. Additionally, the weld metal exhibited the highest yield strength, followed by the fusion zone, the base metal, and the heat-affected zone. Moreover, studies on the fracture toughness KIC of Q235 steel and weld metal E4303 were reviewed. Wilson44 obtained a fracture toughness of approximately 80 \({\text{MPa}}\sqrt {\text{m}}\) using J-integration for AISI1020 steel (similar to Q235B steel). Bauer45 reported a range of 70 \({\text{MPa}}\sqrt {\text{m}}\) to 90 \({\text{MPa}}\sqrt {\text{m}}\) for the fracture toughness of AISI1020 steel. Guan22 employed the boundary effect model and determined the fracture toughness of Q235 steel to be between 68.83 \({\text{MPa}}\sqrt {\text{m}}\) and 83.04 \({\text{MPa}}\sqrt {\text{m}}\). These findings closely align with the fracture toughness KIC of the base metal presented in this paper. Besides, the relative error of the fracture toughness obtained through the BEM in this paper was found to be 0.79% comparing to the average fracture toughness KIC of 128.80 \({\text{MPa}}\sqrt {\text{m}}\) for E4303 weld metal obtained from Charpy impact tests30.

Evaluation of fracture properties of Q235 welded joint using ball indentation method

Brief of critical indentation theory

By the early 1980s, Haggag46 proposed the use of continuous indentation methods to conduct the mechanical properties testing of materials and developed the continuous ball indentation instrument, which is composed as shown in Fig. 9. The ball indentation method is an attractive test method for small specimens and can be employed to evaluate the fracture toughness of materials.

In accordance with Griffith theory on fracture mechanics47, the fracture toughness of an infinitely large flat plate with a crack length of \(2a\), which is subjected to a uniform tensile stress at infinity, can be expressed as Eq. (9). \({\sigma _f}\) represents the far-field tensile stress at fracture of the infinite plate, calculated as Eq. (10). \({\omega _f}\) is the energy absorbed per unit area of the cracked surface produced, and E is the modulus of elasticity. Based on Eqs. (9) and (10), the relationship between fracture toughness and energy absorbed per unit area of the crack surface can be established as in Eq. (11). Although Eqs. (9) and (10) are only applicable to penetration cracks in infinite flat plates, Irwin has shown that Eq. (11) is a generalized relation.

As a result, the determination of the fracture toughness is closely related to \({\omega _f}\), which can be derived from the indentation test. Assuming that there is a point during the indentation test that responds to fracture initiation, to some extent, the deformation indentation region is constrained like the constraint in front of the crack tip48. The energy absorbed per unit contact area of the deformation produced by the indentation test is correlated with \({\omega _f}\). This energy represents the critical indentation energy. By integrating the load over the depth through the load-depth curve of the indentation, an integral equal to \(2{\omega _f}\) is obtained, as shown in Eq. (12). F is the applied load, h is the depth of indentation of the indenter, d is the diameter of the projection circle of the indentation, which is related to D and h as shown in Eq. (13). \({h^ {\ast} }\) as threshold indentation depth at the fracture point. \(2{\omega _f}\) equals to the energy that required to form two cracked surfaces. However, \({h^ {\ast} }\)is difficult to identify.

Under the theory of continuous damage mechanics, Kachanov49 proposed a damage variable M that is correlated with the density of microdefects on the surface of the material. This variable can be expressed as Eq. (14) by using Lemaitre’s equivalent strain principle50, where ED and E are the elastic modulus of the damaged and undamaged material, respectively. Oliver51 proposed that as the indentation depth increases, the damage produced in the material below the indenter (e.g., formation of cavities in ductile materials) tends to increase. Therefore, the elastic modulus of the damaged material ED can be expressed in terms of the indentation test parameters as in Eq. (15), where \(\nu\) and \({\nu _i}\) denote the Poisson’s ratios of the specimen and indenter, respectively. Previous studies have indicated that the Poisson’s ratio remains unaltered by damage accumulation, and Poisson’s ratio of 0.3 was assigned to all materials in this study52. \({E_r}\) is elastic modulus of the reduced contact area of the specimen. The curve is linear during loading, and the loading slope is \({k_F}\),the unloading curve represents the rebound of the material after unloading and the unloading stiffness L is defined as shown in Eq. (16).

The elastic modulus of the damaged material ED when unloaded at different indentation depths can be calculated by Eq. (15). The indentation depth h corresponds to elastic modulus ED at each unloading. The relationship between h and ED can be obtained by fitting \({\operatorname{lnE} _D}\)and \({\text{lnh}}\) linearly, \({{\text{h}}^{{{\ast}}}}\)can be obtained from\({\text{E}}_{{\text{D}}}^{{{{\ast}}}}\). While, \({\text{E}}_{{\text{D}}}^{{{{\ast}}}}\) can be obtained from the critical damage parameter \({\text{M}}^{{\ast}}\) via Eq. (14). During the indentation test, the material is subjected to local shear stresses in the loading direction, which are induced by the downward compressive load. These stresses result in the cavity nucleation, and the cavity rate then increases as the load increases53,54. It is assumed that the voids are uniformly distributed and spaced at a distance l. From Eqs. (17) and (18), Eq. (19) can be derived. r denotes the radius of the hole and f represents the hole rate.

Andersson55 introduced the critical porosity \({f^{\ast}}\)of 0.25 for stable crack expansion in ductile materials. The critical damage parameters \({\text{M}}^{{\ast}}\) and \({\text{E}}_{\text{D}}^{{\ast}}\)can be obtained accordingly, and the critical indentation depth \({{\text{h}}^{{{\ast}}}}\) can be determined, and the fracture toughness KJC can be determined based on Eqs. (11) and (12).

Evaluation of fracture toughness of welded joints via ball indentation test

Ball indentation test

The continuous ball indentation test was completed utilizing the Stress-Strain Microprobe (SSM) system, as illustrated in Fig. 10. The spherical indenter on the test machine consists of two parts: the lever and the tungsten carbide ball indenter, which is welded to the lever matrix. The indentation depth is obtained by measuring the displacement of the indenter downward using a displacement transducer. The accuracy of the displacement transducer is 0.1 per cent of full scale with a resolution of 1 μm, which is sufficient to meet the requirements of the indentation test. Using the continuous indentation loading-indentation depth curve, a physical-mathematical model was established to obtain the fracture toughness of the material. The stress-strain microprobe system has a maximum range of 18.144 kN and tungsten carbide ball indenter diameters of 0.25 mm, 0.51 mm, 0.76 mm, and 1.57 mm. In this test, a tungsten carbide indenter with a diameter of 0.76 mm was employed, with an elastic modulus of 641.212 GPa and a Poisson’s ratio of the indenter of 0.21.

At the commencement of the test, the surface of the material is subjected to a preload of a specified magnitude. The number of cycles of the automatic ball indentation test was set to eight for each test point. The unloading ratio for each cycle was 40% of the maximum load per cycle, with complete unloading at the end. The indenter rate was 0.13 mm/min, and the data acquisition rate of the testing machine was 200 Hz.

To ensure the precision and reproducibility of the test, three specimens were prepared for this test, as displayed in Fig. 11, including S1, S2, and S3. S1 contains a complete welded joint, while S2 and S3 contain half a welded joint. It is noteworthy that the Q235 steel welded joint utilized in this test were manufactured in an identical fabrication as the previous butt-welded joint plate (see Fig. 2). Subsequently, the specimens were sanded on their surfaces by using 320, 400, 600, 800, 1200 and 2000 mesh silicon carbide metallographic sandpaper in turn.

As illustrated in Fig. 12 the load-displacement curves of distinct zones were obtained. It can be observed that the loading slopes \({k_F}\) of different regions varies from zone to zone. The loading slope of the weld metal zone is the largest, followed by the fusion zone, then the heat affected zone, and finally the base metal.

Fracture toughness results

The fracture toughness of various zones in the welded joint was evaluated using the critical indentation theory. The load-depth curves for weld metal obtained from the ball indentation test are presented in Fig. 12. Each curve representing a single test point. In terms of each zone, the three curves exhibit remarkable similarity to each unloading depth, with the exception of each unloading depth. According to Eq. (15), the elasticity modulus ED of the damaged material corresponding to the indentation depth h at 8 unloading can be obtained. The relationship is expression as lnED= − 0.30338lnh + 5.9007, as shown in Fig. 13a. For a critical porosity \({f^ {\ast} }\) of 0.25, the corresponding critical elastic modulus is 109.24 GPa. The critical depth \({{\text{h}}^{{{\ast}}}}\) is 0.0679 mm from the linear relationship between ED and h. Accordingly, the fracture toughness of the weld metal is determined to be 156.711 \({\text{MPa}} \sqrt {\text{m}}\) through Eq. (11) and Eq. (12). The relationship between ED and h can be established in each zone analogously, as shown in Fig. 13. The fracture toughness values obtained from continuous ball indentation tests of welded joints are listed in Table 5.

Linear fitting relationship between lnh and lnED in each zone. (a) Linear fitting relationship between lnh and lnED in weld metal. (b) Linear fitting relationship between lnh and lnED in fusion zone. (c) Linear fitting relationship between lnh and lnED in hot effect zone. (d) Linear fitting relationship between lnh and lnED in base metal.

As illustrated in Table 5, the results of fracture toughness of welded joint zones were obtained via ball indentation method, with a maximum average value of 150.95 \({\text{MPa}} \sqrt {\text{m}}\)in the weld metal zone, a minimum average value of 91.73 \({\text{MPa}} \sqrt {\text{m}}\) in the fusion zone, an average value of 119.97 \({\text{MPa}} \sqrt {\text{m}}\) in the heat affected zone, and an average value of 95.21 \({\text{MPa}} \sqrt {\text{m}}\) in the base metal zone.

As demonstrated in Table 6, the results obtained from the non-destructive ball indentation test were found to be larger than those of the destructive 3-p-b test, with an average relative error ranging from 10.16 to 19.05%. It is noteworthy that the distributions of fracture toughness obtained by non-destructive ball indentation test and destructive 3-p-b test exhibited identical characteristics. The highest fracture toughness was observed in the weld metal, followed by the heat affected zone and the base metal, and the lowest fracture toughness value was found in the fusion zone. The preceding results have demonstrated the applicability and soundness of the non-destructive ball indentation test method and the destructive boundary effect modelling method for the assessment of the integrity of welded joints.

Microstructure of welded joints

The local mechanical properties of welded joints are intricately linked with their microstructures. Thus, investigating microscopic changes in weld metal, fusion zone, heat-affected zone, and base metal becomes crucial for elucidating the alterations in fracture toughness within welded joints.

The metallographic specimens were elaborated as presented in Fig. 14. The microstructure of the welded joint was observed using a CMY-50 inverted metallurgical microscope, as shown in Fig. 15. The microstructures of the metallographic specimens at positions P1, P2, P3 and P4 (see Fig. 14) are shown in Fig. 16a–d. These figures correspond to the microstructures of the weld metal (a), the fusion zone (b), the heat-affected zone (c) and the base metal (d), respectively.

As pictured in Fig. 16a, the weld metal was found to be composed of massive ferrite with a minor component of pearlite and coarse widmanstatten organizations. The plate-like structure of Widmannstetten ferrite creates stress concentration points and easy pathways for crack propagation, resulting in reduced toughness56. The latter feature acicular ferrite or carburizing distributed in the pearlite directionally. The fusion line is faintly visible in Fig. 16b, where the fusion zone displays a semi-grain and coarse grain organization, indicating significant microstructural heterogeneity. Due to its proximity to the weld metal, heat dissipation in the fusion zone is slower, promoting the formation of low-angle grain boundaries and inhomogeneity at the microscopic level. This microstructural inhomogeneity provides favorable conditions for crack initiation, reducing the fracture toughness in the fusion zone of the Q235 butt-welded joints. As shown in Fig. 16c, this section indicates the fine grain area within the heat-affected zone, where the grains were finer and more uniformly distributed. The refinement of grains resulted in an increase in the total surface area per unit volume, which improves the concentration of segregation and reduces the probability of fracture along the grains, which yields an enhancement of the plasticity and fracture toughness of the heat affected zone. In terms of base metal, the grain distribution is homogeneous as demonstrated in Fig. 16d. In comparison to the heat affected zone, the grain organization in base metal appears to be coarser, which accounts for the lower fracture toughness of the base metal than the heat affected zone.

Conclusion

In light of standard measurements of fracture toughness being considered harsh, the application of small volume areas, welded structures or in-service engineering structures is cumbersome, and it is difficult to apply these methods in practical engineering. In this study, the Q235 steel butt-welded joint was selected as the research object. Two different tests were performed on different zones of welded joints: a destructive notched three-point bending (3-p-b) test and non-destructive continuous ball indentation test. The fracture toughness as determined by boundary effect model revealed that the fracture toughness of weld metal, heat affected zone, base metal, and fusion zone were 130.32 \({\text{MPa}}\sqrt {\text{m}}\), 108.91 \({\text{MPa}}\sqrt {\text{m}}\), 83.16 \({\text{MPa}}\sqrt {\text{m}}\), and 77.05\({\text{MPa}}\sqrt {\text{m}}\) respectively. Moreover, the fracture toughness of weld metal, heat affected zone, base metal and fusion zone obtained by ball indentation test were150.95 \({\text{MPa}}\sqrt {\text{m}}\), 119.97 \({\text{MPa}}\sqrt {\text{m}}\), 95.21 \({\text{MPa}}\sqrt {\text{m}}\), and 91.73 \({\text{MPa}}\sqrt {\text{m}}\) respectively. Furthermore, a comparison of the fracture toughness values obtained from the two methods (i.e., boundary effects modelling test and continuous indentation test) revealed that the relative errors in the fracture toughness values were approximately 10.16–19.05%. The results obtained by the indentation method being slightly larger. Moreover, the fracture toughness distributions derived from the two methods were found to be identical. The highest fracture toughness was observed in the weld metal, followed by the heat-affected zone and the base metal, while the lowest fracture toughness was found in the fusion zone. This distribution of fracture toughness aligns with the metallographic results of the welded joints.

Discussion

The fracture toughness values obtained from the ball indentation test for various zones of the Q235 steel welded joint were slightly higher than those obtained from the boundary effect model testing. The boundary effect modelling, as a destructive test, has a larger stress concentration area during the material fracture process, leading to more conservative toughness value. In contrast, the ball indentation test, which does not consider the presence of cracks, reflects the local peak performance of the material, resulting in slightly higher values compared to the destructive boundary effect modelling method. Additionally, this discrepancy may be related to factors such as localized strain hardening, triaxial stress states, microstructural effects, and the inherent limitations of the testing methods.

For integrity evaluation of practical engineering structures, both destructive boundary effect methods and non-destructive ball indentation methods can be used to conduct integrity evaluation at specific locations. For structures in service, or where sampling is not available, it is more practical to employ the ball indentation method to assess fracture toughness. It should be noted that a safety margin should be considered for evaluating the fracture properties of in-service structures by means of non-destructive ball indentation testing.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wang, B., Hu, S. J., Sun, L. & Freiheit, T. Intelligent welding system technologies: state-of-the-art review and perspectives. J. Manuf. Syst. 56:373–91.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmsy.2020.06.020 (2020).

Huang, N., Zhang, J., Zhang, T., Zheng, X. & Yan, Z. Control of Welding Speed and Current in Machine–Human Cooperative Welding processes. Crystals. 12, 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst12020235 (2022).

Arora, K. S., Pandey, S., Schaper, M. & Kumar, R. Effect of process parameters on friction stir welding of aluminum alloy 2219-T87. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 50:941–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-010-2560-3 (2010).

Sheng, X., Zheng, W. & Yang, Y. Tensile and high-cycle fatigue performance of HRB500 high-strength steel rebars joined by flash butt welding. Constr. Building Mater. 241, 118037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118037 (2020).

Takaya, S. Evaluation of fatigue strength of similar and dissimilar welded joints of modified 9Cr-1Mo steel. J. Press. Vessel Technol. 2016;138. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4030932

Alencar, G., Hong, J. K., de Jesus, A., da Silva, J. G. S. & Calçada, R. The Master S-N curve approach for fatigue assessment of welded bridge structural details. Int. J. Fatigue. 152, 106432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2021.106432 (2021).

Park, Y. K. & Shin, J. G. Fatigue strength evaluation of a welded structure by a concentrated load close to the welded joint. Fatigue Strength. Evaluation Welded Struct. Concentrated load. Close Welded Joint. 31, 1789–1796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12206-017-0326-7 (2017).

Lee, K. et al. Real-time Weld Quality Prediction using a laser vision sensor in a lap Fillet Joint during Gas Metal Arc Welding. Sensors. 20, 1625. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20061625 (2020).

Čamagić, I., Sedmak, S. A., Sedmak, A. & Burzić, Z. Influence of temperature on fracture toughness values in different regions of A-387 gr. B welded joint. Procedia Struct. Integr. 18, 205–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prostr.2019.08.155 (2019).

Tang, J., Liu, Z., Shi, S. & Chen, X. Evaluation of fracture toughness in different regions of Weld joints using unloading compliance and normalization method. Eng. Fract. Mech. 195, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2018.03.022 (2018).

Yin, Y., Che, X., Li, Z., Li, J. & Han, Q. Ductile Fracture Analysis of Welded Hollow Spherical Joints Subjecting Axial Forces with Micromechanical Fracture models. Int. J. Steel Struct. 19, 2010–2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13296-019-00261-z (2019).

Zhu, X. K. & Joyce, J. A. Review of fracture toughness (G, K, J, CTOD, CTOA) testing and standardization. Eng. Fract. Mech. 85, 1–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2012.02.001 (2012).

Astm e399-17. Standard test Method for linear-elastic plane-strain Fracture Toughness KIC of Metallic Materials (American Society for Testing and Materials, 2017).

BS 7448-1. Fracture Mechanics Toughness Tests. Part 1: Method for Determination of KIC, Critical COTD and Critical J Values of Metallic Materials (British Standard Institution, 1991).

ISO 12135. Metallic materials-unified Method of test for the Determination of Quasistatic Fracture Toughness (International Organization for Standardization, 2021).

Hu, X. & Wittmann, F. Size effect on toughness induced by crack close to free surface. Eng. Fract. Mech. 65, 209–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0013-7944(99)00123-X (2000).

Hu, X. & Duan, K. Size effect: influence of proximity of fracture process zone to specimen boundary: fracture of materials: moving forwards. Eng. Fract. Mech. 74, 1093–1100 (2007).

Hu, X. & Duan, K. Size effect and quasi-brittle fracture: the role of FPZ. Int. J. Fract. 154, 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10704-008-9290-7 (2009).

Hu, X. & Duan, K. Mechanism behind the size Effect Phenomenon. J. Eng. Mech. 136, 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EM.1943-7889.0000070 (2010).

Hu, X. & Liang, L. Elastic-Plastic and Quasi-Brittle Fracturep. 1–32 (Handbook of Mechanics of Materials, 2018).

Guan, J., Xie, C., Hu, X., Yao, X. & Bai, W. Determination of fracture toughness and yield strength of hot rolled carbon steel based on boundary effect theory. Eng. Mech. 36, 231–239. https://doi.org/10.6052/j.issn.1000-4750.2017.07.0988 (2019).

Guan, J. et al. An elastoplastic fracture model for failure prediction of low-alloy high-strength steel specimen. Eng. Mech. 37, 218–229. https://doi.org/10.6052/j.issn.1000-4750.2019.01.0043 (2020).

Ji, F. Study of the fracture properties of cast aluminium alloy sheet. Master Dissertation. Chang’an University, (2022).

Maeda, K. et al. Indentation-induced ductile behavior of glass-ceramics involving layered aluminosilicates. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 106, 7440–7448. https://doi.org/10.1111/jace.19335 (2023).

Dehm, G., Jaya, B. N., Raghavan, R. & Kirchlechner, C. Overview on micro- and nanomechanical testing: new insights in interface plasticity and fracture at small length scales. Acta Mater. 142, 248–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2017.06.019 (2018).

Gdoutos, E. E. Indentation testing. In: (ed Gdoutos, E. E.) Experimental Mechanics: An Introduction, Cham: Springer International Publishing; 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-89466-5_14. (2022).

Zhang, L. Study on earthquake resistance of rigid beam-to column connection of steel structure. Ph. D. Dissertation. Tianjin University, (2004).

Li, J. Investigation on energy dissipation and accumulative damage of welded beam-to-column connection under earthquake cyclic loading. Ph. D. Dissertation. Tianjin University, (2002).

Wang, Y., Zhou, H., Shi, Y. & Chen, H. Study on Fracture Toughness Indices of Chinese Structural Steel and Weld Metal, p. ISOPE-I-10-406. (2010).

Wang, Y., Zhou, H., Shi, Y. & Chen, H. Fracture behavior analyses of welded beam-to-column connections based on elastic and inelastic fracture mechanics. Int. J. Steel Struct. 10, 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03215835 (2010).

Mohamadizadeh, A., Biro, E. & Worswick, M. Failure characterization and meso-scale damage modeling of spot welds in hot-stamped automotive steels using a hardness-mapping approach. Eng. Fract. Mech. 268, 108506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2022.108506 (2022).

BS EN ISO 9692-. 1:2013: Welding and allied processes. Types of joint preparation. Manual metal arc welding, gas-shielded metal arc welding, gas welding, TIG welding and beam welding of steels 2013.

AWS D1.1/D1.1 M. Structural Welding Code — Steel. Miami, FL: American Welding Society, 2020. (2020).

BS EN ISO 9017:2018. Destructive Tests on Welds in Metallic Materials (Fracture test, 2018).

Wang, L., Feng, Y., Chen, F., Wang, H. & Wang, D. Elasto-Plastic Test of Q235 Steel bending Beam with cracking resistance. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 20, 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1006-706X(13)60197-1 (2013).

Vasco-Olmo, J. M., James, M. N. & Christopher, C. J. Assessment of crack tip plastic zone size and shape and its influence on crack tip shielding. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 39, 969–981. https://doi.org/10.1111/ffe.12436 (2016).

Gonzáles, G. L. G., González, J. O., Paiva, V. E. L. & Freire, J. L. F. Crack-Tip Plastic Zone size and shape via DIC. Fracture, fatigue, failure and damage evolution, 6:5–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95879-8_2 (2019).

Bhowmik, S. & Ray, S. An experimental approach for characterization of fracture process zone in concrete. Eng. Fract. Mech. 211, 401–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2019.02.026 (2019).

Cheng, L., Chen, X., Wei, G. & Fan, Y. Initiation behavior of microscopic short cracks in Weld Toe of Structural Steel Q345B. Metals. 12https://doi.org/10.3390/met12040618 (2022).

Ahmed, B., Bahri, O. C. E., Benattou, B. & Malika, T. Numerical Simulation of a Steel Weld Joint and fracture mechanics study of a Compact Tension Specimen for zones of Weld Joint. Frattura Ed. Integritá Strutturale. 13, 17–29. https://doi.org/10.3221/IGF-ESIS.47.02 (2019).

Li, Y. Analysis of the effect of multiple factors on the plastic zone of the crack tip of a welded joint using finite elements. Master Dissertation. Taiyuan University of Technology, (2002).

Guo, Q. et al. Modelling the crack propagation behavior in 9Cr/CrMoV welds. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 226, 125–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2015.06.004 (2015).

Chen, Y., Han, X., Hu, X., Wang, B. & Zhu, W. A strength criterion for size effect on quasi-brittle fracture with and without notch. Proc. 10th Int. Conf. Fract. Mech. Concrete Concrete Struct. https://doi.org/10.21012/FC10.229373 (2019).

Wilson, M., Hawley, R. & Duffy, J. The effect of loading rate and temperature on fracture initiation in 1020 hot-rolled steel 1980. https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-7944(80)90066-1

Bauer, R. W. & Wilsdorf, H. G. F. Void initiation in ductile fracture. Scr. Metall. 7, 1213–1220. https://doi.org/10.1016/0036-9748(73)90250-0 (1973).

Haggag, F. M. & Lucas, G. E. Determination of lüders strains and flow properties in steels from hardness/microhardness tests. Metall. Trans. A. 14 (8), 1607–1613. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02654388 (1983).

Griffith, A. A. The Phenomena of rupture and flow in solids. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 221 (582–593), 163–198. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.1921.0006 (1921).

Lee, J. S. et al. An instrumented indentation technique for estimating fracture toughness of ductile materials: a critical indentation energy model based on continuum damage mechanics. Acta Mater. 54 (4), 1101–1109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2005.10.033 (2006).

Kachanov, L. M. & Krajcinovic, D. Introduction to continuum damage mechanics. J. Appl. Mech. 54 (2), 481. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3173053 (1986).

Lemaitre, J. A continuous damage mechanics model for ductile fracture. Trans. Asme J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 107, 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3225775 (1985).

Oliver, W. C. & Pharr, G. M. Measurement of hardness and elastic modulus by instrumented indentation: advances in understanding and refinements to methodology. J. Mater. Res. 19 (01), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1557/jmr.2004.19.1.3 (2004).

Li, H., Cai, X. & Cheng, Q. FEM analysis of the effect of interfacial constraint on damage evolution in the film during indentation. Scripta Mater. 45 (12), 1381–1386. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-6462(01)01173-3 (2001).

Fougere, G. E. et al. Young’s modulus of Nanocrystalline Fe measured by nanoindentation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 204 (1–2), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/0921-5093(95)09927-1 (1995).

Yang, M., Akiyama, Y. & Sasaki, T. Evaluation of change in material properties due to plastic deformation. J. Mater. Process. Tech. 151 (1–3), 232–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2004.04.114 (2004).

Andersson, H. Analysis of a model for void growth and coalescence ahead of a moving crack tip. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 25 (3), 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5096(77)90024-2 (1977).

Bodnar, R. L. & Hansen, S. S. Effects of Widmanstätten ferrite on the mechanical properties of a 0.2 pct C-0.7 pct Mn steel. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 25, 763–773. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02665453 (1994).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Technology Support Plan Project (2015BAF07B02), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 11902046), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 51975449), and Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi (Grant Number 2021GY-309). The authors are grateful to other participants of the project for their cooperation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yao Li (First Author): Data curation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing-Original Draft.Tong Jiang: Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing,Visualization.Ling Li (Corresponding Author): Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing, Resources, Funding Acquisition.Pengmin Lu: Supervision, Funding Acquisition, Writing - Review & Editing.Datao Li: Writing - Review & Editing, Review, Funding acquisition. Binhua Wang: Writing - Review & Editing, Funding acquisition.Guozhang Chen: Validation, Writing - Review & Editing.Yulong Hou: Visualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Jiang, T., Li, L. et al. Comparison of destructive and non-destructive fracture toughness measurements for Q235 steel butt-welded joint. Sci Rep 14, 25218 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76687-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76687-1