Abstract

This study aimed to explore the impact of PM 2.5 exposure on survival, post-operative outcomes, and tumor recurrence in resectable non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. The study cohort comprised 587 patients at Chiang Mai University Hospital between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2017. Patients were categorized based on their residents’ average PM 2.5 concentration into two groups: exposed (PM 2.5 ≥ 25 µg/m3 annual mean) and unexposed (PM 2.5 < 25 µg/m3 annual mean). The exposed group had 278 patients, while the unexposed group had 309 patients. Baseline differences in gender and surgical approach were observed between the groups. Multivariable regression analysis revealed that patients in the exposed group had a higher risk of death (HR 1.44, 95% CI, 1.08–1.89, p = 0.012). However, no significant associations were found between PM 2.5 and post-operative pulmonary complications (RR 1.12, 95% CI, 0.60–2.11, p = 0.718), in-hospital mortality (RR 1.98, 95% CI, 0.40–9.77, p = 0.401), and tumor recurrence (HR 1.12, 95% CI, 0.82–1.51, p = 0.483). In conclusion, a PM 2.5 concentration ≥ 25 µg/m3 annual mean was associated with decreased overall survival and a potential increase in in-hospital mortality among resectable NSCLC patients. Larger studies with extended follow-up periods are required to validate these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Particulate matter (PM) in outdoor air pollution was recently designated as a Group I carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC)1. Elevated concentrations of PM 2.5 (ranging between 100 and 200 µg/m3) pose a significant concern in Thailand, particularly during the burning seasons in the northern region, as they have been linked to lung injury and cancer, a leading cause of cancer-related mortality2. Thailand’s national air quality standards, as indicated by the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines and Greenpeace’s City Rankings for MP2.5, fall below WHO recommendations. The annual standard for PM2.5, the most harmful pollutant, is set at 25 micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m3), which is 2.5 times higher than the WHO guideline. Similarly, the daily standard of 50 µg/m3 and annual mean of 25 µg/m3 are double the WHO’s recommendations3,4. Exposure to PM2.5 levels exceeding these thresholds significantly increases the mortality rate from lung cancer5. Additionally, reports indicate that Northern Thai women have the highest incidence of lung cancer in Asia6.

Pulmonary resection is the standard treatment for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)7. However, postoperative complications can lead to prolonged hospital stays, increased medical costs, and higher mortality rates8. In Chiang Mai, Thailand, known for its hazardous levels of PM2.5, the potential relationship between in-hospital mortality, post-operative pulmonary complications, and PM2.5 concentration in surgically treated NSCLC patients remains largely unexplored at the individual-data level within our region and nation. Therefore, the objective of this study is to investigate the association between PM 2.5 exposure and short- and long-term outcomes following pulmonary resection in NSCLC patients.

Methods

Study design and data collection

This is a retrospective cohort study that investigates the effect of PM2.5 on overall survival, in-hospital mortality, postoperative pulmonary complications, and disease-free survival in resectable NSCLC. We obtained approval from the Institutional Review Board (Research Ethics Committee Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University No: 354/2021, Research ID 07877) with a waiver for written informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the study. All data were maintained confidentially following the Helsinki Declaration.

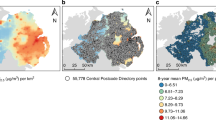

We collected annual concentrations of PM2.5 at background stations divided by patient residence by requesting data from the Chiang Mai Air Quality Health Index (CMAQH) (Website: https://cmaqh.org) from 2007 to 2017). We also review the medical records of adult patients (age > 18 years old) diagnosed with NSCLC who underwent surgical resection in the General Thoracic Surgery Unit, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2017. Patients’ lifestyle modifications were also reviewed.

The patient characteristics such as age, gender, address, smoking status, comorbid disease, stage of NSCLC, operative data, postoperative outcomes, pathologic results, follow-up time, treatment modalities, and patient status, were obtained from the medical recording systems. The primary outcome of this study is overall survival. The secondary outcomes include disease-free survival (recurrent-free survival), in-hospital mortality, and postoperative pulmonary complications such as pneumonia, lung atelectasis requiring bronchoscopy, and re-intubation.

According to previous studies, we divided all patients into two groups based on the upper concentration truncation of PM2.5 at 25 µg/m3 annual mean: the exposed group (≥ 25 µg/m3 annual mean) and the non-exposed group (< 25 µg/m3 annual mean)9. The average concentration of PM 2.5 in the month of surgery was used to investigate the association between PM 2.5 and post-operative pulmonary complications.

We calculated the required sample sizes for a two-sample comparison of survivor functions using an exponential test, hazard difference, and a significance level (alpha) of 0.05 and a power (beta) of 0.20. Our calculations were based on the study by Lepeule et al. (2012), which used overall survival (i.e., overall mortality) as the primary endpoint. The calculated sample size for deceased patients was 97 cases, while for surviving patients it was 1,333 cases, with a ratio of 12.8:1 and a Hazard ratio of 1.37.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were presented as count and percent and analyzed by using Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD), or median and interquartile range (IQR) depending on data distribution and analyzed by using Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test as appropriate. The recurrence-free survival and overall survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier methods. The relationship between PM2.5 exposure (across two study groups) and postoperative pulmonary complications, as well as in-hospital mortality, was examined using a multivariable risk regression model. This model was adjusted for potential confounding factors, including age, gender, Charlson comorbidity index, disease stage, annual PM10 exposure levels, concentrations of CO, SO2, NO2, and O3, as well as average temperature and humidity, all based on patient residency. Additionally, the type of pulmonary resection was taken into account. The estimated values are presented as risk ratios (RR) along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) The association between PM 2.5 and recurrence-free survival and long-term survival were analyzed by multivariable Cox’s regression model adjusted by other confounding factors such as age, gender, Charlson comorbidity index, stage of disease, pathologic result, procedures, concentrations of CO, SO2, NO2, and O3, average temperature and humidity, all based on patient residency, and adjuvant chemotherapy, presented as hazard ratio (HR) with 95% CI. A multiple imputation method for variables with ≥ 10% missing values10 was performed. A modest amount of missing formation is recommended for three to five multiple imputations (< 30%) and then estimate the whole model. After that, the results from a complete-case analysis were compared to those from a multiple imputations analysis. If the final model by multiple imputations gave the same results or had only a slightly different results, we decided to report the result from the complete-case analysis. All tests were two-tailed and performed with Stata 16.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), with p < 0.05 indicating a statistically significant difference.

Results

The results of this study show that a total of 587 patients diagnosed with NSCLC underwent surgical resection, with 278 patients in the exposed group and 309 patients in the unexposed group. The mean age of the exposed group was 62.51 ± 10.52 years, while the exposed group had a mean age of 62.32 ± 10.39 years. Demographic data, preoperative characteristics, and pathologic results are presented in Table 1. Differences in gender and surgical approaches were observed at baseline, while there were no statistically significant differences in age, smoking status, co-morbidity, insurance type, timing between diagnosis and surgery, pathologic stage, cell type, pathologic findings, procedures, occupation, air purifier used in household, and PM2.5 mask use between the two groups. Among the patients, 14.14% were diagnosed with pathological stage IIIB, IIIC, or stage IV disease, despite being initially considered resectable in the preoperative evaluation. These cases included those that were upstaged following lobectomy with systematic lymph node dissection. In patients with stage IV disease, all presented with a single brain metastasis. Management involved either whole brain radiotherapy or craniotomy for resection, depending on the patient’s condition and surgical risk. Subsequently, lobectomy with systematic lymph node dissection was performed.

When comparing between groups and considering other particles, gas concentrations, temperature, and humidity per year based on patient residency, it was observed that the average amount of PM10 and the concentration of CO and NO2 were significantly higher in the exposed group. However, there were no significant differences in terms of SO2 and O3. The mean temperature and humidity per year were also found to be similar between the two groups, as illustrated in Table 2.

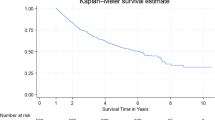

The postoperative treatment outcomes are presented in Table 3. There was no statistically significant difference in terms of postoperative complications, postoperative pulmonary complications, and length of hospital stayed between the two groups. Although there was no statistically significant difference in terms of in-hospital mortality, patients in the exposed group had a higher in-hospital mortality than those in the unexposed group (2.88% vs. 0.97%). In multivariable analysis (Table 4), there was no statistically significant difference in terms of postoperative pulmonary complication and in-hospital mortality. However, patients in the exposed group showed a trend towards higher in-hospital mortality than those in the unexposed group (adjusted HR 1.98, 95%CI = 0.40–9.77). The effect of preoperative PM2.5 exposure on postoperative outcomes was assessed using peak PM2.5 levels corresponding to the patients’ residential addresses during the month of surgery. The analysis showed no significant association between peak PM2.5 levels and postoperative pulmonary complications (adjusted RR = 1.00, 95% CI 0.98–1.02, p = 0.787) or in-hospital mortality (adjusted RR = 1.00, 95% CI 0.96–1.03).In long-term outcomes, patients in the exposed group were more likely to have lower overall survival. The median total follow-up time in the exposed group was shorter than that in the unexposed group (93 months (IQR = 26–132) vs. 124 months (IQR = 56–166), p < 0.001). Figure 1 shows the Kaplan-Meier curve of overall survival, comparing between the two groups. In multivariable analysis (Table 4), patients in the exposed group had a higher risk of long-term mortality (adjusted HR 1.44, 95% CI = 1.08–1.89). Patients in the unexposed group were more likely to survive than those in the exposed group (p = 0.012). There was no statistically significant difference in recurrent-free survival between the two groups, however, patients in exposed group have trend towards higher in tumor recurrence than those in unexposed group (adjusted HR 1.12, 95% CI = 0.82–1.51). The incidence of overall mortality in each month of the year is presented in Fig. 2, where the highest incidence occurred in October and the lowest in September. There was no correlation found between the incidence of overall mortality in each month of the year (r = -0.277, p-value = 0.383).

Discussion

PM2.5 can penetrate deeply into the lungs and irritate the alveolar wall11. It can also cause epigenetic and microenvironmental alterations in lung cancer, including the activation of tumor-associated signaling pathway mediated by microRNA dysregulation, DNA methylation, and increased levels of cytokines and inflammatory cells5. These mechanisms increase the risk of recurrence, disease progression, and postoperative complications in lung cancer patients. Additionally, PM2.5 can affect autophagy and apoptosis of tumor cells, further exacerbating the negative impact on patient outcomes12. We hypothesize that PM2.5 may influence these outcomes, especially respiratory complications. The mechanism by which high PM2.5 levels negatively impact the long-term prognosis after resection in NSCLC can be understood through several biological and environmental pathways. First, chronic inflammation is a key factor, as PM2.5 particles are known to induce sustained inflammation in the respiratory system. Prolonged exposure triggers the continuous release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β, which create a pro-tumorigenic environment. This not only facilitates cancer initiation but also promotes cancer recurrence and progression after resection13. Second, oxidative stress and immune suppression are important contributors. PM2.5 contains toxic metals and organic compounds that generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the lungs. The resulting oxidative stress damages DNA, proteins, and lipids, impairing cellular repair processes and promoting carcinogenesis. Even after surgical resection, ongoing oxidative stress may support the survival of residual tumor cells and facilitate metastasis, thereby worsening the prognosis14. Additionally, PM2.5 exposure has been linked to immune dysregulation, specifically reducing the activity of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and natural killer (NK) cells. These immune cells are essential for eliminating residual cancer cells post-surgery, and their dysfunction increases the likelihood of tumor recurrence and metastasis, ultimately affecting overall survival15. Third, angiogenesis and tumor microenvironment are influenced by PM2.5 exposure, which enhances the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). This promotes angiogenesis, creating a microenvironment conducive to tumor cell survival and growth. After surgical resection, such conditions favor cancer recurrence and disease progression, further contributing to a reduced overall survival rate. PM2.5 exposure also has adverse effects on cardiovascular health, adding an additional layer of risk16. Fourth, genotoxic effects play a role, as PM2.5 has been associated with DNA damage and mutations in key oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, such as p53. These genotoxic effects can persist even after surgical resection, leading to new mutations that drive tumor recurrence or progression, contributing to poorer long-term outcomes17. Lastly, pulmonary function impairment due to chronic PM2.5 exposure is another critical factor. It is associated with decreased lung function and increased prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Patients with compromised pulmonary function are at higher risk for delayed recovery, reduced quality of life, and increased long-term mortality following lung resection18.

In multivariable analysis of this study revealed that the exposed group had an increased risk of long-term mortality, while there was no significant association observed between PM2.5 exposure and postoperative pulmonary complications or tumor recurrence. However, we observed a trend towards an increase in in-hospital mortality among exposed patients. We analyzed data on peak PM2.5 levels corresponding to the patients’ residential addresses during the month of surgery to assess the impact of preoperative PM2.5 exposure on postoperative pulmonary complications and in-hospital mortality. Our analysis revealed no significant association between peak PM2.5 levels and postoperative pulmonary complications or in-hospital mortality. This absence of correlation may be explained by preoperative preparation protocols, which typically include advising patients to cease smoking and use protective masks at least two weeks before surgery. Furthermore, during the postoperative period, patients often wear masks while in the hospital, and air purifiers are in use throughout the facility. These measures likely mitigate the impact of PM2.5 exposure around the time of surgery. However, PM2.5 is known to induce chronic inflammation in the lungs, suggesting that its adverse effects result from a long-term process rather than acute exposure. Thus, preventing PM2.5 inhalation remains essential, not only in the immediate postoperative period but also as part of a lifelong preventive strategy for lung cancer patients, to reduce the risk of recurrence and other long-term complications.

Previous studies have shown that PM2.5 is associated with the incidence and survival of lung cancer19,20,21, and can promote its progression12,22. Some studies have also shown that limited exposure to PM2.5 can decrease the risk of lung cancer and mortality rates in lung cancer patients19.

A recent study by Liu et al.15 examined the effect of ambient PM2.5 exposure on the survival of lung cancer patients after lobectomy and found that every 10 µg/m3 increase in monthly PM2.5 concentration in the first and second months after lobectomy increased the risk of death (HR = 1.043, 95%CI = 1.02–1.07) and HR = 1.036, 95% CI = 1.01–1.06, respectively. Although we did not find a statistically significant difference between PM2.5 and postoperative pulmonary complications, in-hospital mortality, and tumor recurrence, patients in the exposed group had a trend toward a higher risk of postoperative pulmonary complications (adjusted HR = 1.12, 95%CI = 0.60–2.11), in-hospital mortality (adjusted HR = 1.98, 95%CI = 0.40–9.77), and tumor recurrence (adjusted HR = 1.12, 95%CI = 0.82–1.51) compared to the unexposed group.

Based on our data, we found that only 8.3% (49/587 patients) and 5.6% (33/587 patients) of the patients reported using masks and air purifiers at home, respectively. Therefore, we recommend that Thailand, particularly in the northern region, should revise its health promotion and policy strategies to prevent forest fires and improve air quality. Economic growth is important, but it should be balanced with environmental protection to ensure sustainable development. Additionally, public health education and promotion campaigns are essential.

There are some limitations to this study. First, the retrospective nature of the study design may have introduced selection bias in surgical cases. Second, the number of patients who used masks or air purifiers was too small to be used for further data analysis. We attempted to explore the association between mortality and the seasonal high values of PM2.5, but we did not find any association. The available sample size was not powered enough to detect any significant associations among PM2.5, recurrent-free survival, postoperative pulmonary complication, and in-hospital mortality. Therefore, larger studies with longer follow-up periods are required to validate the findings of this study. Third, data on epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation status is not available in this study, which may influence treatment decisions in cases of tumor recurrence or metastasis and potentially affect long-term survival. Future studies that incorporate EGFR mutation data would be highly valuable.Conclusions.

In conclusion, our study suggests that high PM 2.5 concentration is associated with increased long-term mortality in resectable NSCLC patients and may also affect in-hospital mortality. Further investigations with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods are needed to confirm these findings.

Data availability

All data are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are available upon request from Effect of PM2.5 on Mortality, Tumor Recurrence, and Postoperative Complications in Resectable Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma: A Retrospective Cohort Study should be sent to apichat.t@cmu.ac.th and are subject to approval by the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University Ethics Committee.

References

Poirier, A. E., Grundy, A., Khandwala, F., Friedenreich, C. M. & Brenner, D. R. Cancer incidence attributable to air pollution in Alberta in 2012. CMAJ Open. 5 (2), E524–E8. https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20160040 (2017). PubMed PMID: 28659352; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5498315.

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Jemal, A. & Cancer statistics CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7–30. Epub 20200108. doi: (2020). https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21590. PubMed PMID: 31912902.

Greenpeace’s City Rankings for PM2.5 in Thailand. https://greenpeace.or.th/s/right-to-clean-air/PM2.5CityRankingsREV.pdf

WHO Air Quality Guidelines. https://www.c40knowledgehub.org/s/article/WHO-Air-Quality-Guidelines?language=en_US

Li, R., Zhou, R. & Zhang, J. Function of PM2.5 in the pathogenesis of lung cancer and chronic airway inflammatory diseases. Oncol. Lett. 15 (5), 7506–7514 (2018). Epub 20180326. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8355. PubMed PMID: 29725457; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5920433.

Pongpiachan, S. et al. Chemical characterisation of organic functional group compositions in PM2.5 collected at nine administrative provinces in northern Thailand during the Haze Episode in 2013. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 14 (6), 3653–3661. https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.6.3653 (2013). PubMed PMID: 23886161.

Wu, C. F. et al. Recurrence risk factors analysis for stage I non-small cell Lung Cancer. Med. (Baltim). 94 (32), e1337 (2015). .0000000000001337. PubMed PMID: 26266381; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4616676.

Nakada, T. et al. Risk factors and cancer recurrence associated with postoperative complications after thoracoscopic lobectomy for clinical stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac. Cancer. 10 (10), 1945–1952. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-7714.13173 (2019). Epub 20190821.

West SCAaJJ. The Global Burden of Air Pollution on Mortality: Anenberg. Respond. Environ. Health Perspect. 119 (4), 158–159. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1003276R (2011). PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3080949.

Shrive, F. M., Stuart, H., Quan, H. & Ghali, W. A. Dealing with missing data in a multi-question depression scale: a comparison of imputation methods. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 6, 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-6-57 (2006). Epub 20061213.

Pun, V. C., Kazemiparkouhi, F., Manjourides, J., Suh, H. H. & Long-Term PM2.5 exposure and respiratory, Cancer, and Cardiovascular Mortality in older US adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 186 (8), 961–969. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwx166 (2017). Epub 2017/05/26.

Chao, X. et al. PM(2.5) exposure increases the risk of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) progression by enhancing interleukin-17a (IL-17a)-regulated proliferation and metastasis. Aging (Albany NY). 12 (12), 11579–11602 (2020). Epub 20200618. doi: 10.18632/aging.103319. PubMed PMID: 32554855; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7343463.

Ghio, A. J. & Devlin, R. B. Inflammatory lung injury after bronchial instillation of air pollution particles. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 164 (4), 704–708. https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.2011089 (2001). PubMed PMID: 11520740.

Xia, T., Kovochich, M. & Nel, A. The role of reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress in mediating particulate matter injury. Clin. Occup. Environ. Med. 5 (4), 817–836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coem.2006.07.005 (2006). PubMed PMID: 17110294.

Liu, C. et al. The effect of ambient PM(2.5) exposure on survival of lung cancer patients after lobectomy. Environ. Health. 22 (1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-023-00976-x (2023). Epub 20230307.

Sun, Y. et al. Exposure to PM2.5 via vascular endothelial growth factor relationship: Meta-analysis. PLoS One. 13 (6), e0198813. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198813 (2018). Epub 20180618.

Loomis, D. et al. The carcinogenicity of outdoor air pollution. Lancet Oncol. ;14(13):1262-3. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70487-x. PubMed PMID: 25035875. (2013).

Liu, Q. et al. Association between long-term exposure to ambient particulate matter and pulmonary function among men and women in typical areas of South and North China. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1170584. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1170584 (2023). Epub 20230512.

Yang, L. et al. The PM(2.5) concentration reduction improves survival rate of lung cancer in Beijing. Sci. Total Environ. 858 (Pt 2), 159857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159857 (2023). Epub 20221031.

Wen, J., Chuai, X., Gao, R. & Pang, B. Regional interaction of lung cancer incidence influenced by PM(2.5) in China. Sci. Total Environ. 803, 149979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149979 (2022). Epub 20210828.

Liu, Y. et al. Short-term association of PM 2.5 /PM 10 on lung cancer mortality in Wuhai city, China (2015–2019): a time series analysis. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 31 (6), 530–539 (2022). Epub 20220602. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000764. PubMed PMID: 35671253.

Chen, Z. et al. Fine particulate matter (PM(2.5)) promoted the Invasion of Lung Cancer cells via an ARNT2/PP2A/STAT3/MMP2 pathway. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 14 (12), 2172–2184. https://doi.org/10.1166/jbn.2018.2645 (2018). PubMed PMID: 30305224.

Acknowledgements

This study was partially supported by Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand.

Funding

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.T. designed study, checked quality of collected data and quality assurance, performed the statistical analyses, evaluated the results, and revised the manuscript. B.K., T.W., N.N., and P.W. collected the data and contributed substantially to data preparation and first draft of manuscript. P.P., B.K., T.W., N.N., P.W., S.S., S.S., and B.C. participated in the conception and design of the study. S.S., S.S., and B.C. revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have read, reviewed, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kosanpipat, B., Wongwut, T., Norrasan, N. et al. Impact of PM2.5 exposure on mortality and tumor recurrence in resectable non-small cell lung carcinoma. Sci Rep 14, 24660 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76696-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76696-0