Abstract

Electrospinning is a specialized processing technique for the formation of submicron diameter fibers of polymeric and ceramic materials using an electrostatic field. The process has multiple advantages over other nano- and micro- fiber synthesis methods; however, generally suffers from very low fabrication speeds, making it undesirable for scalability. This work assesses the performance of a needle-less, self-contained, high throughput electrospinning system. It further compares the fiber fabrication rates obtained versus two single needle setups with different collectors: (i) a conventional single needle and flat plate geometry, and (ii) a single needle with a rotating collector geometry. Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) in ethanol was used as the model material. The fabrication rate of the high throughput system “HTES” was measured at about 2.6 g/h and was about 15 times that collected of the flat plate. Comparing it to other systems reported in the literature also proved it to be a viable option for high throughput, lab scale electrospinning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Principles of electrospinning

Electrospinning refers to a specialized processing technique for the formation of submicron diameter fibers of certain materials including polymers using an electrostatic field. The concept of electrospinning is not new and has been studied since the late 1800s and early 1900s1. However, few publications in the field existed before the 20th century when the chemical fiber industry became prominent2. Three main components comprise an electrospinning setup: the spinneret, the voltage supply, and the collector. During the process, a precursor solution is extruded through the tip of a capillary tube situated in an electrostatic field. The electrostatic field weakens the surface tension of the solution droplet, which gradually forms into a conical shape known as the Taylor cone3. When the electrostatic repulsive force of the field overcomes the surface tension of the solution, the droplet is stretched into an electrically charged jet of fluid from the tip of the Taylor cone4. Finally, the jet splits into fibers which deposit onto the grounded collector.

Generally, the objective of the electrospinning process is to obtain smooth, continuous fibers of the smallest diameter possible. The factors that influence this result can be designated into the following two categories: solution properties and process parameters. Solution properties that affect fiber morphology consist of surface tension, viscosity, and conductivity. Process parameters that affect morphology consist of applied voltage, solution flow rate, spinneret-to-collector (working) distance, and external environment, which can include ambient humidity, temperature, and gas4. Due to the breadth of affecting parameters, creating an encompassing formula to fabricate smooth, uniform fibers has been difficult. Further issues that can arise during the electrospinning process include stray fibers unattracted to the collector due to an insufficient voltage drop between the spinneret and collector, as well as clogging of the spinneret. As the spinneret is often a needle, repeated clogging requires excessive cleaning that can greatly slow the production rate of fibers.

Applications of functional fibers

Electrospinning is not the only way to produce nanofibers, as other methods of fabrication include templating5, phase separation6, melt blowing7, and self-assembly8. However, of these processes, electrospinning shows the most promise for commercially scaled-up systems. This viability is important considering the breadth of fields that can benefit from the implementation of nanofibrous materials. The high aspect ratio, small pore size, and flexible alignment are attractive properties for a variety of fields including filtration, tissue engineering, water splitting, and electronic/smart clothing.

In the filtration industry, important properties of fiber-base filters include filter efficiency, flux, and pressure drop9. Nonwoven mats prepared via electrospinning can have smaller fiber diameters and interconnected porosity, leading to a large increase in filter efficiency via the sieve effect, while only having a slight increase in pressure drop10. For example, a study by Scholten et al. demonstrated that micron-sized electrospun fibers of polyurethane had a comparable sorption capacity of volatile organic compounds to that of activated carbon despite having a lower surface area11. Additionally, the nonwoven meshes had the ability to completely reverse absorption and desorption (achieved by purging with nitrogen at room temperature), unlike activated carbon where this sorption is irreversible. The fibers specifically held strong attraction towards toluene and chloroform, making them appealing materials for these filters.

Tissue engineering aims to fabricate material constructs to maintain, restore, or improve damaged tissue. These goals are accomplished by combining scaffolds, cells, and sometimes growth factors to induce a response in the tissue to self-assemble, which can mend damaged tissue or create new ones. For artificially induced tissue growth, the key is mimicking the extracellular matrix (ECM) as it is responsible for relaying signals to cells that begin the growth process. Naturally, materials used in tissue engineering must be bio-compatible to mimic the biological functionality of the ECM. Research completed by Gouma’s group12 illustrated the successful use of electrospinning in fabricating a multilayered structure that mimicked the topology of a porcine urinary bladder ECM. CA was used as an organic polymer with low water solubility. The CA scaffolds were also shown to have success in growing functional cardiac cell constructs13 further proving its bio-functionality.

With the rapidly increasing energy needs associated with large population growth and the focus on environmental damages associated with the use of fossil fuels, there is a greater demand now more than ever for sources of clean, renewable energy. Much attention has been paid to hydrogen as a potential fuel source14, due to its atmospheric availability in water vapor and likewise release of only water vapor when combusted. Unfortunately, most of the world’s current hydrogen generation is from natural gas and other fossil fuels15. However, photocatalytic water splitting has been proven by Gouma to be a reliable clean source of hydrogen generation16. Furthermore, research by Gouma et al. has proven that this photocatalytic process can be completed by electrospun mats17. In this research, a process of sol-gel electrospinning was employed to synthesize nanowires of brookite TiO2 into self-supported nanocrystalline grids.

The structure of the resultant fibrous mat is dependent on the collector used during electrospinning; a flat plate collector may be used to obtain a thin, flat mat of randomly oriented fibers, or a rotating barrel drum may be used to obtain aligned fibers. More recently, research has been conducted in manufacturing three-dimensional (3D) electrospinning fibers for use in woven applications. Work by Joseph et al.18 has shown how a unique collector employing spindles is able to manufacture a 3D “fluffy mass” of fibers with mechanical properties similar to a cotton ball. With similar mechanical properties to a cotton ball, it has been proposed that this mass could be processed through conventional textile manufacturing techniques to make yarn for smart textiles. These smart textiles could be active stimuli-sensing (include temperature, pH, light, electrical, magnetic, etc19). , or passive antibacterial or antistatic.

High throughput electrospinning

As mentioned before, one of the biggest challenges in electrospinning is the slow speed of the process: deposition of 5 ml of solution can take anywhere from 1.5 to 3.5 h (and perhaps longer) depending on the processing parameters. Looking at the listed applications, the need for this technology to become commercially viable and not just laboratory experiment is apparent.

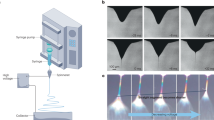

Superficially, a multi-needle apparatus seems to be the logical solution for increasing the fiber fabrication rate of an electrospinning setup, a schematic of such is shown in Fig. 1a. However, as each needle is charged using the same potential, jet-to-jet interactions can cause the fibers to repel each other and drastically influence the final production of fibers20. Additionally, as is a challenge with single needle setups, the issue of clogging and repetitive cleaning is exacerbated by the use of more needle spinnerets and can lead to a much lower yield. Nevertheless, research has been conducted by multiple groups using a variety of multi-needle geometries have successfully demonstrated a high fiber output21,22,23.

To ameliorate the clogging issue, another high throughput electrospinning method draws fibers up from a solution reservoir in multiple jets that then deposit onto an above collector (see Fig. 1b). Research groups have employed varying configurations using this reservoir method. For example, Thoppey et al.24 developed a bowl-edge geometry, where the solution is placed in a central bowl. The electric field then draws fibers up from the circumference of the bowl and onto a larger surrounding collector. This method allows the solution jets to naturally space out to minimize inter-jet interactions. Additionally, as the solution is not pushed through a long capillary tube or needle, clogging does not occur. A top view of this geometry is illustrated in Fig. 1c. Figure 1d shows a setup for bubble electrospinning, which was first demonstrated in 2007 by Liu et al.25. The apparatus uses gas from an electrically charged nozzle to push bubbles up through the solution reservoir. As the bubbles form on the surface, multiple conical jets form similar to the Taylor cone on each bubble resulting in a high production of fibers on the collector.

These needle-less electrospinning setups seem to be a promising solution for the clogging and cleaning issues of traditional and multi-needle electrospinning. However, these geometries come with their own drawbacks. Specifically, using a large surface area of open solution can accelerate volatilization of the solvent, causing premature drying of the solution and providing a potential health risk in the case of more toxic solvents. When the surface of the solution dries, it may be necessary to remove the top layer of the reservoir to provide a fresh layer of material, which adds a new, complicated step to the entire process as well as significantly lowers the yield26.

An ideal high throughput electrospinning setup would have the multi-jet function without the need for long needles that tend to clog, and without the need for an open reservoir of solution that may prematurely dry. Research conducted by Sood et al. resulted in such an apparatus that allowed for multiple jets to form without using an open reservoir27. This system employs a hollow circular disk with multiple, short-length capillary holes around the circumference. The circular disk is charged and fed by a continuous supply of the desired polymeric solution. The disk spinneret is then placed in the center of a surrounding grounded collector so that jets on all sides are equidistant from the collector. The multiple capillary holes around the circumference of the disk allow for multiple Taylor cones to form, much like a multi-needle geometry. However, unlike a multi-needle geometry, the Taylor cones are faced away from each other at a critical angle that allows for an acceptable amount of jet overlap without said jets repelling each other and lowing the overall yield. The shorter lengths of the capillary holes also mean the solution is less likely to clog within the holes. As the extruder disk in enclosed, the solvent does not prematurely dries or require refreshing. This prototype setup along with the circular disk spinneret are pictured in Fig. 2a and b.

The high throughput electrospinning setup in this study used the extruder and collector geometry from the prototype, but greatly improved the design by allowing for the collector to rotate, avoiding the discrete circles of deposition as seen in the Fig. 2a, to a continuous, uniform deposition that covers nearly the entire collector. In addition to this change, the system also combines the traditionally separated fluid pump and power supply into a self-contained machine, ideally for desktop use. This improved design is pictured below in Fig. 2c and d.

High throughput electrospinning prototype and improved system used in this study. (a) HTES prototype extruder and collector electrospinning discrete mats of fibers. (b) Hollow disk extruder top (left) and bottom (right) with capillary holes. The 12 larger holes on top are for screws to attach the two halves. (c) Improved HTES setup used in this study with collector, fluid pump, and power supply labelled. (d) Inside the collector with extruder disk and collector labelled.

Electrospinning is a greatly promising fabrication method for very high aspect ratio fibers; however, in addition to the process’s temperamental nature, the process also suffers from incredibly low fabrication rates. Conventional electrospinning setups only produce an average of 0.01 –1 g of fibers per hour. If the method is to be applicable at commercial/industrial levels, then more investigation needs to be conducted on electrospinning configurations to increase fiber fabrication rates. Studies testing multiple different “high through electrospinning systems” can be found in the literature as discussed above, but these setups often struggle with disadvantages such as premature solvent evaporation and/or extensive clogging. Therefore, there is still a need for a setup that sufficiently scales up fiber fabrication while avoiding most, if not all, the disadvantages of previous setups.

The purpose of this work was to investigate the electrospinning fiber fabrication rate and morphology of different electrospinning geometries. The former is a half-sized model of a spindle collector first shown by Joseph et al.18, which is rotated via a home-made low RPM motor using COTS (commercial off-the-shelf) parts. The second is the improved, compacted model of the high throughput electrospinning system previously developed by Gouma’s research group27 and fabricated using The Edward Orton Jr’s Ceramic Foundation’s resources (Fig. 2c). This system will be referred to as the “HTES” for simplicity and is believed to pass the requirements for a scaled-up electrospinning system. The study compared the fiber production rate, fiber diameter, and fiber orientation of both geometries to a conventional electrospinning setup.

Results

The conventional electrospinning setup with the flat plate produced a thick, nonwoven fibrous mat that covered approximately the entire collector plate (see Fig. 3a). SEM images of one of the flat plate samples at different magnifications can be seen in Fig. 3b and c. SEM images for this sample were taken with the Phenom ProX as it displayed better resolution for high charging samples.

The electrospinning set up with the rotating spindle collector also produced a thick, nonwoven mat wrapped around the collector (Fig. 4a and b). Figure 4c and d displays the SEM images for a sample of the top side of the collector while Fig. 4e and f displays the SEM images for a sample of the side of the collector.

The electrospin with the HTES created a thick nonwoven mat similar to the flat plate collector. However, the sample was much larger at about 36 cm x 119 cm (see Fig. 5a and b below). Figure 5c and d displays the SEM images for this sample.

Figure 6 below illustrates the results of the fabrication rate and average fiber diameter for each tested electrospinning configuration.

Discussion

The HTES in this study had a fabrication rate of about 15 times that of the flat plate setup. This is lower than the theoretical quantity of 24 times due to the 24 extruder holes, however the fabrication rate is still high for a non-industrial electrospinning setup. For comparison: Thoppey24 recorded a fiber production rate of about 0.265 g/h for a 90-minute spin time and 0.684 g/h for a 20-minute spin time on the bowl-edge electrospinning setup. This production rate is about 9.7 and 3.7 times lower respectively than the recorded rate of the HTES setup for this investigation. Compared to more recent advances, this electrospinning setup falls within the range of other lab-scale high throughput systems. Often, it comes with the added benefit of not needing extremely high voltages (+ 40 kV), having to mitigate inter-jet interaction, or having a large quantity of solvent open to the atmosphere as discussed earlier. See below for Table 1 comparing fabrication rates in the literature of other high throughput systems to the one investigated here, as well as to conventional electrospinning.

The rotating collector setup had a fiber fabrication rate of about 0.5 times that of the flat plate setup. This was expected as the geometry of the collector is much more intricate and contains more negative space than that of the flat plate. Consequently, the rotating collector setup displayed the highest amount of stray fiber production; fibers that deposited on surfaces other than the collector and therefore were not included in the fabrication rate calculations. A substantial amount of fibers needed to be swiped from the fume hood walls and cables during the experiment. Fibers also had collected onto the motor attached to the rotating collector. The benefit of this setup is the ability to deposit both aligned and randomly oriented fibers, which could be useful in experiments where the effects of fiber alignment are investigated (see Fig. 7).

Looking at the fiber quality of the different setups, one can see that for the flat plate and rotating collector electrospins, the fibers seem to be paired up after splitting from the Taylor cone. Most likely these fibers would fully separate under a stronger electric field or a longer working distance. There is also the possibility that a less viscous precursor (less amount of PVP) would result in fully separated fibers; however, this must be done delicately in order to avoid the solution from hitting the collector too quickly once in contact with the electric field, resulting in “splats” and wet fibers webbing together.

The flat plate collector showed the smallest average fiber diameter at 643 nm, this was expected as this setup had the simplest geometry. The rotating collector had the next smallest average fiber diameter at 856 nm and 706 nm for the top and side of the collector, respectively. The fibers on the sides were slightly smaller due to the mechanical force of the rotation pulling on the fibers as they are collected. These fibers were also more uniform than any other geometry with an average fiber diameter error of 1 nm. Another interesting observation is that on the top surface, the fibers seemed to tangle and wind around each other creating an almost yarn-like structure. The HTES had a larger average fiber diameter of 2595 nm and one can see in the SEM images that the fibers seemed to be beginning to split but were unable to before contact with the collector. Again, this could potentially be mitigated using a higher applied voltage or a less viscous precursor (here, a less concentrated PVP + EtOH solution).

Although resulting in microfibers here, the geometry of the HTES has been previously proven to result in nanoscale electrospun fibers. The earlier prototype by Sood using the same collector and hollow disk extruder (pictured in Fig. 2a), was used to fabricate nanofibers of PVP and CA. In this experiment, the concentration of PVP was about 10 wt%34. This also supports the prediction that the current HTES model would produce smaller diameter fibers using a less viscous precursor solution. In addition to this result, the prototype was also used to create nanowires of MoO3 using sol-gel electrospinning, predicting that the new modelled HTES could be using for the fabrication of ceramic nanowires.

Conclusion

Fiber fabrication rates were investigated between different electrospinning geometries including a new, self-contained high throughput electrospinning system, which employs the use of a hollow disk spinneret. 13 w/v PVP in ethanol was used for all electrospinning experiments. The high throughput system was found to produce fibers 15 times faster than the conventional, single-needle setup with an average fabrication rate of 2.6 g/h. The fibers were observed to be smooth if larger than that of the single-needle setup, however this can be mitigated through use of a less viscous precursor and/or a higher applied voltage. Comparison with other high throughput electrospinning geometries showed that this system is a viable option for lab-scale high throughput electrospinning applications. Future work is expected to focus on continual improvement of the device into a self-contained, desktop electrospinning apparatus for lab and small business purposes.

Methods

All experiments were completed using a 13 w/v solution of 1,300,000 g/mol number-average molecular weight PVP (Sigma Aldrich) in 200 proof Ethanol (Decon Laboratories, inc.). A traditional electrospinning setup with a single needle spinneret and a flat plate collector was used as a basis for comparison of fiber fabrication rate and quality. This experiment was completed with 8 mL of the PVP + EtOH solution in a 10 ml plastic syringe and 20 G needle. The syringe was pumped at a rate of 1.6 ml/h using a syringe pump (KD Scientific). A positive lead supplying 17 kV was connected to the needle from a high voltage supply (Gamma High Voltage Research). The working distance used was 13 cm. The collector was a 25.5 cm x 25.5 cm flat metal plate.

The rotating spindle electrospin was completed with similar parameters to the flat plate: 8 ml of the PVP + EtOH in a 10 ml plastic syringe, 20 G needle, flow rate of 1.6 mL/h, positive 17 kV supplied voltage, 13 cm working distance. The spindle collector was oriented to face the single extruder needle and was rotated approximately at 750 RPM.

Electrospinning experiments using the HTES varied slightly from the previous experiments. 100 mL of the PVP + EtOH solution was pumped at a rate of 80 RPM using the integrated fluid pump from an Erlenmeyer flask into the hollow disk spinneret. 17 kV was applied to the spinneret from the integrated power supply. The working distance between the edge of the spinneret and the surrounding collector drum was 13 cm. The collector drum was rotated clockwise at low – medium speed to ensure a continuous mat of fibers would be deposited. Images of the setups can be viewed in Supplementary Fig. S1-S3 online.

Each setup was run in triplicate. Once completed, all samples underwent the same processes for analysis. Each was weighed on a standard scale and calculated against the flow rate of the solution to get the sample fiber fabrication rate in g/h. N.b., in order to keep the structural integrity of the large HTES samples, equivalent pieces of aluminum foil to the ones the samples rested on were cut, rolled and weighed. The sample along with the foil it rested on was then weighed. The weight of the respective piece of empty foil was then subtracted from its counterpart to obtain the weight of only the electrospun sample. Samples were imaged in a Phenom proX desktop Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) as well as a Thermo Scientific Apreo SEM. The images were then analyzed in ImageJ to measure average fiber diameter for each setup. Fibers of each sample were measured in 10 different places and averaged for an average fiber diameter. A weighted average diameter was then calculated per electrospinning setup.

Each setup was run in triplicate. Once completed, all samples underwent the same processes for analysis. Each was weighed on a standard scale and calculated against the flow rate of the solution to get the sample fiber fabrication rate in g/h. N.b., in order to keep the structural integrity of the large HTES samples, equivalent pieces of aluminum foil to the ones the samples rested on were cut, rolled and weighed. The sample along with the foil it rested on was then weighed. The weight of the respective piece of empty foil was then subtracted from its counterpart to obtain the weight of only the electrospun sample. Samples were imaged in a Phenom proX desktop Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) as well as a Thermo Scientific Apreo SEM. The images were then analyzed in ImageJ to measure average fiber diameter for each setup. Fibers of each sample were measured in 10 different places and averaged for an average fiber diameter. A weighted average diameter was then calculated per electrospinning setup.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. Supplementary images of the setups can be viewed in the supplementary information file.

References

Tucker, N., Stanger, J. J., Staiger, M. P., Razzaq, H. & Hofman, K. The History of the Science and Technology of Electrospinning from 1600 to 1995. J. Eng. Fib. Fabric. 7(2_suppl), 155892501200702S. https://doi.org/10.1177/155892501200702S10 (2012).

Gouma, P. A novel nanomanufacturing technique for Hybrid nanofibers and their non-woven mats, in Nanomaterials for Chemical Sensors and Biotechnology. Singapore: Pan Stanford Publishing Pte. Ltd., 71–83. (2010).

Taylor, J. B. & Bullard, E. C. The magneto-hydrodynamics of a rotating fluid and the earth’s dynamo problem, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Math. Physic. Sci. 274(1357), 274–283. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1963.0130 (1963).

Mikaeili, F., Abe, O. O. & Gouma, P. I. High-throughput Electrospinning of Biomaterials, in Additive Manufacturing in Biomedical Applications, vol. 23A, (ed Narayan, R. J.) ASM International, 0. (2022).

Ugo, P. & Moretto, L. M. 16.2 - TEMPLATE DEPOSITION OF METALS, in Handbook of Electrochemistry, C. G. Zoski Ed pp. 678–709 (Elsevier, 2007).

Jung, A. et al. Phase separation–controlled assembly of hierarchically porous Aramid Nanofiber films for high-speed Lithium-metal batteries. small 18(52), 2205355. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202205355 (2022).

Zuo, F. et al. Nanofibers from Melt Blown Fiber-in-Fiber polymer blends. ACS Macro Lett., 2(4), 301–305. https://doi.org/10.1021/mz400053n (2013).

Xu, D., Samways, D. S. K. & Dong, H. Fabrication of self-assembling nanofibers with optimal cell uptake and therapeutic delivery efficacy. Bioactive Mater., 2(4), 260–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2017.09.001

Jung, S. & Kim, J. Advanced Design of Fiber-Based Particulate Filters: Materials, Morphology, and Construction of Fibrous Assembly, (in eng). Polymers (Basel). 12(8), https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12081714 (2020).

Qin, X. & Subianto, S. in 17 - Electrospun Nanofibers for Filtration Applications. 449–466 (eds Nanofibers, E. & Afshari, M.) (Woodhead Publishing, 2017).

Scholten, E., Bromberg, L., Rutledge, G. . C. . & Hatton, T. . A. . Electrospun Polyurethane Fibers for Absorption of Volatile Organic Compounds from Air,. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. https://doi.org/10.1021/am200748y (2011).

Han, D. & Gouma, P. I. Electrospun bioscaffolds that mimic the topology of extracellular matrix. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2(1), 37–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nano.2006.01.002 (2006).

Entcheva, E. et al. Functional cardiac cell constructs on cellulose-based scaffolding, (in eng). Biomaterials 25(26), 5753–5762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.01.024 (2004).

Anstrom, J. R. 17 - hydrogen as a fuel in transportation, in Advances in Hydrogen Production, Storage and Distribution, (eds A. Basile, A. & Iulianelli, A.) 499–524 (Woodhead Publishing, 2014).

Chouhan, N., Liu, R. S. & Jiujun, Z. Photochemical Water Splitting: Materials and Applications (CRC, 2017).

Mikaeili, F., Gilmore, T. & Gouma, P. I. Photochemical Water Splitting via Transition Metal Oxides, (in English). Catalysts 12(11), 1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal12111303 (2022).

Mikaeili, F. Visible Light Self Supported TiO2 Based Photocatalysts, Doctor of Philosophy (Materials Science and Engineering, The Ohio State University, 2021).

Joseph, J., Nair, S. V. & Menon, D. Integrating Substrateless Electrospinning with Textile Technology for Creating Biodegradable Three-Dimensional Structures. Nano Letters 15(8), 5420–5426. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b01815 (2015).

Liu, L. et al. A review of smart electrospun fibers toward textiles. Compos. Commun. 22, 100506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coco.2020.100506 (2020).

Theron, S. A., Yarin, A. L., Zussman, E. & Kroll, E. Multiple jets in electrospinning: experiment and modeling. Polymer 46(9), 2889–2899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2005.01.054 (2005).

Beaudoin, É. J., Kubaski, M. M., Samara, M., Zednik, R. J. & Demarquette, N. R. Scaled-Up Multi-Needle Electrospinning Process Using Parallel Plate Auxiliary Electrodes. Nanomaterials 12(8), 1356 (2022).

Zhu, Z. et al. Nanofibrous membrane through multi-needle electrospinning with multi-physical field coupling. Mater. Res. Exp. 8(7), 075012. https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/ac1510 (2021).

Zhu, Z. et al. Uniform electric field enabled multi-needles electrospinning head based on trapezoid arrangement. AIP Adv. 8, 085126. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5026908 (2018).

Thoppey, N. M., Bochinski, J. R., Clarke, L. I. & Gorga, R. E. Edge electrospinning for high throughput production of quality nanofibers, (in eng). Nanotechnology 22(34), 345301. https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/22/34/345301 (2011).

Liu, Y. & He, J. H. Bubble Electrospinning for Mass Production of Nanofibers. Int. J. Nonlinear Sci. Num. Simulat. 8(3), 393–396. https://doi.org/10.1515/IJNSNS.2007.8.3.393 (2007).

Wu, D. et al. High-throughput rod-induced electrospinning. J. Phys. D. 49(36), 365302. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/49/36/365302 (2016).

Sood, S., Divya, S. & Gouma, P. High Throughput Electrospinning of 3D Nano Fibrous Mats. J. Nanoeng. Nanomanufact. 4(1), 39–44 (2014).

Omer, S., Forgách, L., Zelkó, R. & Sebe, I. Scale-up of Electrospinning: Market Overview of Products and Devices for Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Purposes, (in eng). Pharmaceutics, 13(2), https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics13020286 (2021).

Jiang, G., Zhang, S. & Qin, X. High throughput of quality nanofibers via one stepped pyramid-shaped spinneret. Mater. Lett. 106, 56–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2013.04.084 (2013). 0

Wang, X., Niu, H., Lin, T. & Wang, X. Needleless electrospinning of nanofibers with a conical wire coil. Poly. Eng. Sci. 49(8), 1582–1586. https://doi.org/10.1002/pen.21377 (2009).

Rouxi, C. et al. Bubble Rupture Bubble Electrospinning Therm. Sci., 19(4), https://doi.org/10.2298/TSCI1504141C (2015).

Dosunmu, O. O., Chase, G. G., Kataphinan, W. & Reneker, D. H. Electrospinning of Polymer nanofibres from multiple jets on a porous tubular surface, nanotechnology, 17(4), 1123. https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/17/4/046 (2006).

Xiong, J. et al. Mass production of high-quality nanofibers via constructing pre-taylor cones with high curvature on needleless electrospinning. Mater. Design, 197, 109247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2020.109247 (2021).

Sood, S. Polymorphism Control in Nanostructured Metal Oxides, Ph.D. dissertation, Mat Sci and Eng, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, 2014. [Online]. Available: http://hdl.handle.net/11401/77825

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mohammad Mahafuzur Rahaman for assistance with the SEM images taken via the Thermo Scientific Apreo SEM. The authors would also like to thank The Edward Orton Jr. Ceramics Foundation for their assistance in fabricating the HTES. Additionally, the financial support provided by the Accelerator Awards at The Ohio State University is also acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: T.G., P.G.; Data collection: T.G.; Analysis and interpretation of results: T.G.; Draft manuscript preparation: T.G.; Manuscript editing: T.G., P.G.; Funding acquisition: P.G. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gilmore, T.S., Gouma, PI. Scalable electrospinning using a desktop, high throughput, self-contained system. Sci Rep 14, 25844 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76766-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76766-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Review: harnessing engineered electrospun materials for efficient CO2 conversion into value-added products

Journal of Materials Science (2025)