Abstract

Aza-Diels–Alder cycloaddition reaction is a critical synthetic method for the production of bioactive tetrahydroquinolines. To this aim, an imine obtained from the reaction of an aniline derivative and a carbonyl compound is cyclized with an alkene in the presence of a catalyst. In this research, some tetrahydroquinoline compounds are synthesized through aza-Diels–Alder reaction in the presence of a prepared Ce(III) immobilized on the functionalized halloysite (Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA) as a catalyst. Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA was prepared by incorporation of aminopropyl silane on the halloysite surface, followed by treatment with 2,4,6-trichloro-1,3,5-triazine (TCT) and iminodiacetic acid (IDA), and loading cerium nitrate. Then, it was characterized and analyzed by different analytical methods, indicating the amorphous agglomerated grains (20–60 nm), containing 0.00196 mmol g−1 Ce(III) ions. The catalytic activity and reusability of Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA were studied in this research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

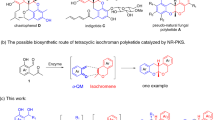

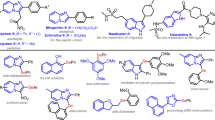

Tetrahydroquinolines (THQs) are a category of important natural and synthetic organic compounds, showing a wide variety of bioactivities, from antiparasite activities to antitumor properties1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Moreover, THQ scaffold has become attractive as an effective electron-donating dye for the performance of dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs)9,10,11,12,13. Therefore, the development of simple and effective production of THQs has been keenly studied14,15,16. O’Byrne and Evans synthesized 2-alkyl THQs through the reaction of quinoline with alkyl lithium, followed by reduction under hydrogen gas (Fig. 1a)17. Due to the important role of catalysts in the promotion of organic reactions18,19,20,21, the focus of many studies is on the intermolecular cyclization of N-alkyl-N-methylaniline and maleimides through C–H activation and the formation of radical intermediates using various initiators and catalysts (Fig. 1b), such as Cu(OAc)2/t-butyl hydroperoxide22, K2S2O823, organic framework photocatalyst24, copper ferrite nanoparticles (CuFe2O4)25, and benzaldehyde as the photoinitiator26. Aza-Diels–Alder cycloaddition between an N-phenylimine and an alkyne or one-pot Aza-Diels–Alder cycloaddition of aniline, aldehyde, and alkene is a favorable route for the synthesis of THQs, as illustrated in Fig. 1c 16,27.

Cerium salts are categorized as an important class of metal catalysts in organic reaction, including oxidation of various functional groups, generation of carbon–heteroatom bonds, esterification reactions, ring-opening reactions, thioglycosidation, C–H bond formation, and others28,29,30. Feng et al. demonstrated that Ce(III) is an efficient catalyst in cascade Michael addition, cyclization, and aromatization to approach pyrrolo[1,2-a]quinolines31. In another study, Ce(III) could catalyze cyclization reactions between aminopyridines and nitroolefins to form pyridyl benzamides32. Moreover, the applicability of Ce(III) in the C–H functionalization has been approved33,34. Therefore, Ce(III) has an essential role in organic syntheses.

A wide range of C=C containing frameworks are employed in the aza-Diels–Alder reaction for the synthesis of THQs, including α,β-unsaturated hydrazones35, 2-vinylindoles36, N-vinyl-pyrrolidin-2-one37, indoles38, 2,3-dihydrofuran39, and so on. In addition, many catalysts have been developed to promote this cycloaddition reaction, such as sulfonic acid functionalized metal–organic frameworks40, helquats41, Fe(III)-phenanthroline complex42, chiral phosphoric acid43, FeCl344, trifluoromethanesulfonic acid-immobilized nitrogen-doped carbon45. Following our studies46,47,48,49,50, in this research we tried to prepare an efficient catalyst through loading Ce(III) on the surface of functionalized halloysite. The activity of this prepared catalyst was then investigated in the aza-Diels–Alder reaction for the synthesis of THQs.

Experimental

Materials and instruments

All chemicals, salts, and solvents used in this study were purchased with high purity in analytical grade from Merck Company, including (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES), 2,4,6-trichloro-1,3,5-triazine (TCT), iminodiacetic acid (IDA), potassium carbonate, cerium nitrate, cyclopentadiene, styrene, maleic anhydride acetonitrile, toluene, dichloromethane, ethanol, acetic acid, ethyl acetate, and hexane.

The obtained catalyst was characterized by various analytical techniques, including X-ray diffraction (XRD), Philips, Netherlands, model PW1730. Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were recorded between 4000 and 400 cm−1 on a Thermo Nicolet, USA, AVATAR 370, and using KBr pellet. Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) images along with an energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analysis were obtained using a MIRA 3-XMU Tescan instrument, Czech Republic, with an acceleration voltage of 20 kV. To measure the leaching amounts of cerium ions from the catalyst surface, an inductively coupled plasma of ICP-AES using a Vista-pro device, Agilent (HP), California, USA, was employed. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) was performed on Netzsch-TGA 209 F1. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker, 300 and 75 MHz, respectively.

General procedure: synthesis of Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA

Synthesis of Hal-NH2

Anhydrous CaSO4 was gradually introduced into 50 mL of toluene until the particles appeared dry, rather than wet and muddy. Then, the mixture was distilled, and the first 5 mL was thrown away, to obtain dry toluene. Halloysite (2 g) was dispersed in dry toluene (25 mL) via sonication for 20 min. Then, APTES (8 mL) was slowly added, and the mixture was refluxed for 48 h at 110 °C. Then, the obtained aminopropyl functionalized halloysite was separated using centrifugation, washed with dry toluene three times for removal of the remaining APTES, and dried at 100 °C overnight.

Synthesis of Hal-TCT

To introduce the TCT heterocycles on the surface of Hal-NH2, 1.5 g of the latter was dispersed in THF (50 mL) under ultrasonication for 20 min, then TCT (6.5 mmol, 1.2 g) was gradually added to the mixture at 0 °C (in an ice bath) during 1 h. Upon completion of adding the chemicals, the mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 24 h. Finally, the obtained Hal-TCT was separated using centrifugation, washed well with THF for removal of untreated TCT, and dried at 80 °C within 8 h.

Synthesis of Hal-TCT-IDA

During 15 min, Hal-TCT (1.2 g) was dispersed in dry toluene (30 mL) within 15 min, then K2CO3 (0.5 g, 3.6 mmol) and IDA (15 mmol, 2 g) were added to the mixture and dispersed. The reaction mixture was refluxed for 12 h at 100 °C. The obtained Hal-TCT-IDA was separated using centrifugation, washed well with toluene, and dried for 8 h at 80 °C.

Synthesis of Ce/Her-TCT-PDA

A mixture of Ce(NO3)3⋅6H2O (1.5 mmol, 0.5 g) and Hal-TCT-IDA (1.2 g) was dispersed in acetonitrile (40 mL), and the mixture was refluxed for 12 h. Then, the obtained compound was separated using centrifugation, washed well with MeCN three times, and finally dried at 80 °C.

General procedure of aza-Diels–Alder reaction

The synthesis of (E)-N-benzylideneaniline (1)

A mixture of aniline (10 mmol, 0.93 mL), benzaldehyde (10 mmol, 0.1 mL), and two drops of glacial acetic acid as the catalyst was stirred in EtOH at room temperature for 8 h. The mixture was cooled in an ice bath to precipitate product 1, then, filtered, and washed well with cold EtOH for removal of untreated reactants. The product was stored in the refrigerator for next reactions.

Aza-Diels–Alder reaction

(E)-N-Benzylideneaniline 1 (1 mmol, 0.18 g) and dieneophile (1 mmol) were dissolved in CH2Cl2, containing Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA catalyst (0.05 g), and the mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for the relevant time shown in Table 2. The product was insoluble in CH2Cl2, therefore, it was simply filtered off and washed with cold CH2Cl2 for the removal of untreated reactants.

Spectral data

2,4-Diphenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (3a)

IR (KBr) v (cm−1): 3395 (NH), 3047 (= C–H), 2921 and 2835 (C–H), 1600, 1565, 1494, and 1438 (C–C ring), 1461 (CH-CH2-CH), 743 (NH). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 2.33–2.53 (2H, m, CH2), 4.09 (1H, m, CH), 4.45 (1H, bs, NH), 4.57 (1H, m, CH–N), 6.68 (1H, td, J = 5 Hz, Ar–H), 6.88 (1H, dd, J = 5 Hz, Ar–H), 7.03 (1H, dt, J = 10 Hz, Ar–H), 7.08 (1H, td, J = 5 Hz, Ar–H), 7.30 (10H, m, Ar–H). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 40.0, 44.3, 53.6, 115.2, 122.9, 126.6, 126.7, 126.8, 127.4, 128.2, 128.3, 128.4, 129.6, 142.0, 144.3, 144.9.

4-Methyl-2,4-diphenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (3b)

IR (KBr) v (cm−1): 3399 (NH), 3041 (= C–H), 2921 and 2831 (C–H), 1630 (NH out of plane), 1601, 1519, and 1494 (C–C ring), 1462 (CH2-CH), 741 (NH). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 1.45 (3H, s, Me), 2.35–2.51 (2H, m, CH2), 4.49 (1H, m, CH), 4.02 (1H, bs, NH), 4.48 (1H, m, CH–N), 6.68 (1H, td, J = 5 Hz, Ar–H), 6.84 (1H, dd, J = 5 Hz, Ar–H), 7.01 (2H, m, Ar–H), 7.30 (10H, m, Ar–H). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 28.9, 52.6, 113.9, 122.2, 126.0, 126.7, 127.6, 127.8, 128.2, 128.3, 133.7, 142.7, 145.5, 149.0.

4-Phenyl-3a,4,5,9b-tetrahydro-3H-cyclopenta[c]quinoline (3c)

IR (KBr) v (cm−1): 3391 (NH), 3056 (= C–H), 2922 and 2851 (C–H), 1625 (NH out of plane), 1601, 1494, and 1435 (C–C ring), 742 (NH). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 2.22–2.45 (2H, m, CH2), 2.73 (1H, m, CH), 4.5 (1H, q, J = 5 Hz, CH–N), 4.78 (1H, m, CH), 4.84 (1H, s, NH), 5.85 (2H, m, CH = CH), 6.78 (1H, dd, J = 5 Hz, Ar–H), 6.98 (1H, td, J = 5 Hz, Ar–H), 7.03 (1H, dt, J = 5 Hz, Ar–H), 7.15 (1H, td, J = 5 Hz, Ar–H), 7.25–7.9 (5H, m, Ar–H). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 40.6, 50.2, 56.4, 115.4, 123.7, 127.2, 127.8, 128.2, 128.2, 128.3, 128.4, 134.2, 136.8, 140.6, 143.7.

Results and discussion

Catalyst preparation

Since halloysite is a kind of aluminum silicate compound, hydroxyl groups are accessible on its surface, making it modifiable. Consequently, we used silane reagent APTES to introduce aminopropyl groups on halloysite surface through chemical bonds to give Hal-NH2, as shown in Scheme 1. Then, TCT was added to react with amine groups via the SN2 mechanism, furnishing a C–N bond in Hal-TCT. Furthermore, the remained C–Cl groups of grafted TCT moieties could be replaced with another amine group present in the structure of IDA to give Hal-TCT-IDA. Finally, cerium nitrate was incorporated on the latter to obtain the target catalyst Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA. As halloysite is a heterogeneous substrate with a catalytic nature, incorporation of a Lewis acid on it makes it a highly active catalyst that can be used in many organic synthesis. To ensure the success of the Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA synthesis, various analytical methods were employed to characterize its structure, including FT-IR, SEM images, IDAX, XRD, and TGA.

Catalyst characterization

The prepared Hal-TCT and Hal-TCT-IDA were initially studied using FT-IR. As shown in Fig. 2, the stretching vibrations of methylene groups of APTES at 2976, 2925, and 2891 cm−1 are observable in the spectrum of Hal-TCT (Fig. 2, inset), approving the introduction of an aminopropyl groups on the halloysite surface. Moreover, the band at 3278 cm−1 is as a result of C=C–H vibrations of the small amount of adsorbed toluene solvent on the silica surface. Due to the high concentration of halloysite in comparison with the grafted APTES, the intensity of APTES absorption bands is weak in Hal-TCT. The observed bands at 3697 and 3626 cm−1 in Hal-TCT and Hal-TCT-IDA spectra denote the stretching vibrations of inner hydroxyls of Al–OH. The wide band around 1038 indicates in-plane stretching vibrations of Si–O and Si–O–Si groups, and the sharp band at 910 cm−1 recalls the Si–OH deformation vibration. The Si–O stretching vibrations are also observable around 793 cm−1. The band at 536 cm−1 is due to the Al–OH deformation vibrations. Furthermore, Hal-TCT-IDA shows all the absorption bands of IDA, confirming the high concentration loading of IDA groups. Consequently, the bands at 3097 and 3020 cm−1 result from the vibration of hydroxyl groups of IDA’s carboxylic acids.

The bands at 1714, 1583, and 1396 cm−1 indicate the vibration of C=O in carboxylic acid groups. The Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA spectra shows no changes in comparison with those observed for Hal-TCT-IDA, indicating the maintenance of the quality and integrity of the substrate for loading the Ce(III)51. It must be noted that Ce–O stretching vibration appears at 520 cm−1, which cannot be traced due to overlapping with other bands. It is important to mention that Ce(NO3)3 salt shows a strong and sharp absorbance band at 1464 cm−1, which is not observed in Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA FT-IR spectrum. This fact confirms that all nitrate anions were washed out and were replaced with triazine and/or carboxylate anions during complexation.

The morphology characteristics of the Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA were studied through SEM images (Fig. 3). Figure 3a,b give an overview of the accumulation of catalyst nanoparticles, which are amorphous agglomerated grains with sizes in the range of 20–60 nm (Fig. 3c,d). EDX analysis of Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA (Fig. 4) confirms the presence of C and N atoms, attributed to the organic moieties, Al and Si atoms, which constitute the structure of halloysite, and Ce atom with 0.6 wt%. Moreover, Fig. 5 illustrates the X-ray mapping of Ce/Hal-TCT-catalyst, showing good dispersion of all expected elements, including C, N, O, Al, Si, and Ce, in the scaffold of the catalyst. The absence of Cl is the reason for substitution of all C–Cl groups with IDA. These characteristics approve the successfulness of the halloysite modification with organic molecules through the grafting method and incorporation of cerium ions on its surface via physical interactions.

The curves of thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential thermogravimetry (DTG) for Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA are shown in Fig. 6-up and -down, respectively. The weight loss (2%) before 80 °C is due to the removal of free water. The second DTG peak at 143 °C belongs to the removal of adsorbed solvents (1%). Moreover, the mentioned process is accompanied by the release of CO2 gas resulted from the decomposition of carboxylic acids in the structure of IDA. Consequently, these pyrolysis processes are observable around 203 °C in the DTG curve with a weight loss of 17%. Then, the next DTG peaks are observed at 303 and 343 °C, which respectively show 10% and 20% mass loss resulted from the decomposition of organic moieties grafted on the halloysite surface. The further mass loss after 500 °C is attributed to the condensation of surface Al–OH and Si–OH groups. Consequently we observed 47% weight loss for the pyrolysis of TCT-IDA groups. According to the data obtained by EDX analysis, 0.6 wt% of the catalyst sample belongs to the Ce atom. We know that Ce(NO3)3 with a molecular weight of 325.87 g mol−1 contains 42.93% and 12.89% of Ce and N atoms, respectively. Therefore, it can be concluded that 1.4% of the final catalyst mass belongs to this compound. Accordingly, about 45.6% mass loss of the TGA curve results from the decomposition of the grafted organic structure with the molecular weight of 399.13 g mol−1. Finally, about 1.82 mmol g−1 TCT-IDA was grafted on the halloysite surface, while 0.00196 mmol g−1 cerium atom was loaded on it.

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA is shown in Fig. 7. Based on the reported pattern for halloysite and various Ce(III) forms in literature51,52,53,54, the appeared peaks were identified. Correspondingly, the peaks that are usually appeared for Ce(III) were observed at (111), (200), (220), and also (311) planes with the 2θ degrees of 29.4, 34.0, 47.5, and 57.5°, respectively55,56.

According to the published study by Sharif et al. 57, Ce(III) forms complex A through one nitrogen and two oxygen atoms of pyridine-2,4,6-tricarboxylic acid, as depicted in Scheme 2. The complexation was confirmed by crystallographic data. In another research, Oh-e and Nagasawa found that strong interactions occur between Ce(III) and de-protonated diglycolic acid (complex B) through three oxygen atoms and confirmed it using fluorescence spectra58. Recently, Zhao et al. designed a series of MOFs (complex C) by complexation of triazine tricarboxylic acid with M(III) rare earth ions. X-ray single-crystal structure analysis of the formed complexes revealed the binding of two metal ions with each carboxylic acid groups59. Another study confirmed the formation of Fe(III) complex D bridged by carboxylic acids using various analytical techniques60. Therefore, the neighborhood of nitrogen atoms of TCT with IDA carboxylates’ oxygen atoms in Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA raises the possibility that cerium cations are attached to the TCT-IDA ligands through their oxygen and nitrogen atoms, as depicted in Scheme 2.

Catalytic study

Cerium(III) is an active Lewis acid, and its complexes have catalyzed many organic reactions, including protection of ethers, esterification, alkylation of coumarins, allylation of aldehydes, condensation cyclization of 1, 3-diketones, and hetero-Diels–Alder reactions 61,62,63,64,65. Due to the diverse catalytic usage of Ce(III) in organic synthesis, it was loaded on the modified halloysite surface to make a strong complex to be heterogenized. Then, its catalytic activity was tested in Aza-Diels–Alder reaction. In this regard, imine 1a–e was initially synthesized through the condensation of in an ethanol solution of aniline derivative and benzaldehyde in the presence of 3–4 drops of acetic acid as the catalyst (Scheme 3). Then, the obtained (E)-N-benzylideneanilines 1a–e was employed in the Aza-Diels–Alder reaction with styrene to modify the reaction condition.

The catalytic activity of Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA was tested in an aza-Diels–Alder reaction. We started with the screening of reaction conditions using a model aza-Diels–Alder cyclization between imine 1 and styrene 2 to give tetrahydroquinoline 3 (Table 1). Running the reaction in dichloromethane at room temperature gives the highest yield of the expected product after 12 h (Table 1, entry 3). By increasing temperature, the efficiency of this reaction drops (entries 4 and 5), indicating its sensitivity to heat. Not much product is obtained in the absence of catalyst (entry 6). When the amount of catalyst was changed, 0.1, 0.3, and 0.07 g (entries 7–9) didn’t make more output than 0.05 g of catalyst. The low efficiency of this cyclization in MeCN, EtOH, and toluene (entries 10–12) shows the tendency of this reaction to the nonpolar, aprotic solvents, due to the formation of nonpolar intermediates. The π–π stacking interaction of toluene with the reactants leads to the electron distribution, decreasing their reactivity. To study the effect of Ce(III) on promotion of this reaction, the model reaction was run in the presence of cerium nitrate (Table 1, entry 13). The reaction yield was favorable, showing the catalytic impact of Ce(III). Consequently, complexing this ion on the surface of the Hal-TCT-IDA makes it more effective and recoverable.

Having the modified conditions, the scope of Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA-catalyzed aza-Diels–Alder reaction was thereafter examined, as summarized in Table 2. Interesting, the presence of a methyl group on styrene (reactant 2b) had no negative effect on the progress of reaction, resulting in the formation of product 3b in high yield. Moreover, the use of cis-diene 2c didn’t cause competitive reactions, and no side products were formed. Electron-withdrawing nature of the anhydride group of maleic anhydride 2d leads to a drop of cyclization yield.

Reaction mechanism

As mentioned before, Ce(III) can act as a Lewis acid to promote cyclization reactions31,66,67,68. Consequently, a proposed mechanism for the Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA catalyzed tetrahydroquinoline synthesis is suggested in Scheme 4. According to the mechanisms reported in literature 16, Ce(III) of the catalyst activates the diene reactant 1 through its nitrogen atom to react with the dienophile reactant 2 via a [4 + 2] cycloaddition mechanism.

Reusability of catalyst

Due to the importance of recyclability of a catalyst, the used Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA was recycled and reused in the model cyclization reaction. Correspondingly, we collected 0.5 g of the used Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA, and washed it well with hot CH2Cl2 to remove the adsorbed chemical substances. Subsequently, the dried Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA was introduced for a subsequent run under the same reaction conditions. Figure 8 portrays the yield of each cycle, and compares them with the very first run. As it can be observed, after eight cycles, the reaction efficiency was dropped to only 15%, which approves the useful catalytic usage of Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA in cyclization reactions.

Besides, the drop in catalytic productivity of Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA after the fifth run is possibly owing to the pollution of the catalyst surface due to the considerable adsorption of organic substances that are not separated by solvent washing. Using an atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS with a limit of detection of 3.0 μg L−1), followed by the catalyst separation after cycles 1–3, the content of the leached Ce(III) was determined in the reaction mixtures, and no noticeable level was observed. Figure 9 depicts the XRD pattern of the run 8 recycled catalyst, which shows drop in the intensity of Ce(NO3)3 peaks in comparison with the pattern of the fresh catalyst in Fig. 7. This means that a considerable amount of the loaded cerium was strongly fixed on the substrate using the grafted ligands on the halloysite surface, although it may be leached into the reaction mixture after several usages of the catalyst due to mechanical stirring. Moreover, FTIR of the recycled catalyst showed no observable changes, as illustrated in Fig. 10, confirming that the structure of the catalyst is not collapsed after recovery.

Comparison of the aza-Diels–Alder catalysts

There are many published studies that focus on the application of various simple and chiral catalysts in the aza-Diels–Alder reaction. Table 3 summarized a few studies regarding the use of catalytic aza-Diels–Alder reaction. Literature survey reveals that such reaction can be accomplished at low temperature in the presence of a catalyst, because non-catalytic aza-Diels–Alder reaction occurs at low energy barriers of 17.0–29.6 kcal mol−1. Thus, the use of a catalyst can reduce this barrier to promote the reaction at room temperature69. Moreover, Brønsted or Lewis acids are suitable to catalyze this reaction due to the ionic nature of the formed intermediates70. The current study can be run under neat conditions at room temperature within a few hours and the catalyst is reusable. However, selectivity of the Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA catalyst to obtain optically active products was not determined. In the future, we will examine enantio- or diastereoselectivity of Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA in aza-Diels–Alder reactions.

Conclusion

As a conclusion, we developed a halloysite-based catalyst by incorporation of aminopropyl silane on its surface, followed by treating with TCT and IDA, and loading cerium nitrate. The obtained Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA was analyzed by different characteristic methods, indicating the presence of amorphous agglomerated grains with sizes in the range of 20–60 nm, which 1.82 mmol g−1 TCT-IDA and 0.00196 mmol g−1 Ce(III) were incorporated on it. Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA was then able to efficiently catalyze aza-Diels–Alder reaction to give tetrahydroquinolines. This research shows that halloysite is a good candidate to be used as a substrate for the formation of hybrid catalysts. Moreover, Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA can actively catalyze the organic reaction and reuse with no significance drop in its efficiency because the loaded cerium was strongly fixed on the modified halloysite using the grafted ligands. Consequently, Ce/Hal-TCT-IDA can efficiently catalyze those reactions that are promoted in the presence of cerium nitrate.

Data availability

All data and materials were provided in the manuscript and readers can contact to corresponding author to receive additional explanation.

References

Goli, N., Mainkar, P. S., Kotapalli, S. S., Ummanni, R. & Chandrasekhar, S. Expanding the tetrahydroquinoline pharmacophore. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 27, 1714–1720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.02.077 (2017).

Gosmini, R. et al. The discovery of I-BET726 (GSK1324726A), a potent tetrahydroquinoline ApoA1 up-regulator and selective BET bromodomain inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 57, 8111–8131. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm5010539 (2014).

Quan, M. L. et al. Tetrahydroquinoline derivatives as potent and selective factor XIa inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 57, 955–969. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm401670x (2014).

Fathy, U., Abd El Salam, H. A., Fayed, E. A., Elgamal, A. M. & Gouda, A. Facile synthesis and in vitro anticancer evaluation of a new series of tetrahydroquinoline. Heliyon 7, 08117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08117 (2021).

Tejería, A. et al. Antileishmanial activity of new hybrid tetrahydroquinoline and quinoline derivatives with phosphorus substituents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 162, 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.10.065 (2019).

Schmidt, R. G. et al. Chroman and tetrahydroquinoline ureas as potent TRPV1 antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 21, 1338–1341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.01.056 (2011).

Dai, Z. et al. Development of novel tetrahydroquinoline inhibitors of NLRP3 inflammasome for potential treatment of DSS-induced mouse colitis. J. Med. Chem. 64, 871–889. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01924 (2021).

Alqasoumi, S. I., Al-Taweel, A. M., Alafeefy, A. M., Ghorab, M. M. & Noaman, E. Discovering some novel tetrahydroquinoline derivatives bearing the biologically active sulfonamide moiety as a new class of antitumor agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 45, 1849–1853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.01.022 (2010).

Chen, R. et al. Effect of tetrahydroquinoline dyes structure on the performance of organic dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem. Mater. 19, 4007–4015. https://doi.org/10.1021/cm070617g (2007).

Chen, R., Yang, X., Tian, H. & Sun, L. Tetrahydroquinoline dyes with different spacers for organic dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 189, 295–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2007.02.018 (2007).

Hao, Y., Yang, X., Cong, J., Hagfeldt, A. & Sun, L. Engineering of highly efficient tetrahydroquinoline sensitizers for dye-sensitized solar cells. Tetrahedron 68, 552–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2011.11.004 (2012).

Roy, J. K., Kar, S. & Leszczynski, J. Insight into the optoelectronic properties of designed solar cells efficient tetrahydroquinoline dye-sensitizers on TiO2(101) surface: First principles approach. Sci. Rep. 8, 10997. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29368-9 (2018).

Rakstys, K. et al. A structural study of 1-phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline-based dyes for solid-state DSSC applications. Dyes Pigm. 104, 211–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dyepig.2014.01.010 (2014).

Ngamnithiporn, A., Welin, E. R., Pototschnig, G. & Stoltz, B. M. Evolution of a synthetic strategy toward the syntheses of bis-tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloids. Acc. Chem. Sci. 57, 1870–1884. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.4c00262 (2024).

Sridharan, V., Suryavanshi, P. A. & Menéndez, J. C. Advances in the chemistry of tetrahydroquinolines. Chem. Rev. 111, 7157–7259. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr100307m (2011).

Hosseini, A., Motavalizadehkakhky, A., Ghobadi, N. & Gholamzadeh, P. In Advances in Heterocyclic Chemistry Vol. 140 (eds Scriven, E. F. V. & Ramsden, C. A.) 45–66 (Academic Press, 2023).

O’Byrne, A. & Evans, P. Rapid synthesis of the tetrahydroquinoline alkaloids: Angustureine, cuspareine and galipinine. Tetrahedron 64, 8067–8072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2008.06.073 (2008).

Liu, Y. et al. A H4SiW12O40-catalyzed three-component tandem reaction for the synthesis of 3,3-disubstituted isoindolinones. Chin. Chem. Lett. 35, 108480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108480 (2024).

Hu, Q., Li, K., Chen, X., Liu, Y. & Yang, G. Polyoxometalate catalysts for the synthesis of N-heterocycles. Polyoxometalates 3, 9140048. https://doi.org/10.26599/POM.2023.9140048 (2024).

Li, K. et al. Highly-stable silverton-type UIV-containing polyoxomolybdate frameworks for the heterogeneous catalytic synthesis of quinazolinones. Green Chem. 26, 6454–6460. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4GC00877D (2024).

Liu, Y.-F. et al. Three polyoxometalate-based Ag–organic compounds as heterogeneous catalysts for the synthesis of benzimidazoles. Inorg. Chem. 63, 5681–5688. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.4c00114 (2024).

Prasanna Kumari, S., Naveen, B., Suresh Kumar, P. & Selva Ganesan, S. Cu/TBHP mediated tetrahydroquinoline synthesis in water via oxidative cyclization reaction. Chem. Pap. 77, 151–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11696-022-02462-z (2023).

Yadav, A. K. & Yadav, L. D. S. Intermolecular cyclization of N-methylanilines and maleimides to tetrahydroquinolines via K2S2O8 promoted C(sp3)–H activation. Tetrahedron Lett. 57, 1489–1491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.02.078 (2016).

Zhao, Y. et al. Missing-linker defects in a covalent organic framework photocatalyst for highly efficient synthesis of tetrahydroquinoline. Green Chem. 26, 2645–2652. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3GC04566H (2024).

Pham, H. H., Nguyen, A. C. D., Nguyen, C. T. D., Phan, N. T. S. & Nguyen, T. T. Annulation of N, N-dimethylanilines and maleimides catalyzed by reusable copper ferrite nanoparticles. Tetrahedron Lett. 107, 154108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tetlet.2022.154108 (2022).

Nikitas, N. F., Theodoropoulou, M. A. & Kokotos, C. G. Photochemical reaction of N, N-dimethylanilines with N-substituted maleimides utilizing benzaldehyde as the photoinitiator. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 1168. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejoc.202001593 (2021).

de Paiva, W. F., de Freitas Rego, Y., de Fátima, Â. & Fernandes, S. A. The Povarov reaction: A versatile method to synthesize tetrahydroquinolines, quinolines and julolidines. Synthesis 54, 3162–3179. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1794-8355 (2022).

Sridharan, V. & Menéndez, J. C. Cerium(IV) ammonium nitrate as a catalyst in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 110, 3805–3849. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr100004p (2010).

Fischer, S., Groth, U., Jeske, M. & Schütz, T. Cerium(III)-catalyzed addition of diethylzinc to carbonyl compounds. Synlett 2002, 1922. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2002-34897 (2002).

Bartoli, G. et al. Cerium(III) chloride catalyzed Michael reaction of 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds and enones in the presence of sodium iodide under solvent-free conditions. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 617–620 (1999).

Feng, C., Yan, Y., Zhang, Z., Xu, K. & Wang, Z. Cerium(III)-catalyzed cascade cyclization: An efficient approach to functionalized pyrrolo[1,2-a]quinolines. Org. Biomol. Chem. 12, 4837–4840. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4OB00708E (2014).

Chen, Z. et al. Ce(III)-catalyzed highly efficient synthesis of pyridyl benzamides from aminopyridines and nitroolefins without external oxidants. Org. Biomol. Chem. 16, 1247–1251. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7OB03113K (2018).

An, Q. et al. Cerium-catalyzed C-H functionalizations of alkanes utilizing alcohols as hydrogen atom transfer agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 6216–6226. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.0c00212 (2020).

An, Q. et al. Identification of alkoxy radicals as hydrogen atom transfer agents in Ce-catalyzed C-H functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 359–376. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.2c10126 (2023).

Clerigué, J., Ramos, M. T. & Menéndez, J. C. Mechanochemical Aza-Vinylogous Povarov reactions for the synthesis of highly functionalized 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinolines and 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-1,5-naphthyridines. Molecules 26, 1330 (2021).

Suzuki, T., Kuwano, S. & Arai, T. Non-bonding electron pair versus π-electrons in solution phase halogen bond catalysis: Povarov reaction of 2-vinylindoles and imines. Adv. Synth. Catal. 362, 3208–3212. https://doi.org/10.1002/adsc.202000494 (2020).

Güiza, F. M. et al. Crystal structure, Hirshfeld surface analysis, and molecular dynamics simulations of two isostructural N-propargyl-4-(2-oxopyrrolidin-1-yl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinolines. J. Mol. Struct. 1254, 132280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.132280 (2022).

Schendera, E. et al. Visible-light-mediated aerobic tandem dehydrogenative povarov/aromatization reaction: Synthesis of isocryptolepines. Chem. Eur. J. 26, 269–274. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201903921 (2020).

Coelho Pimenta, J. V., Sabino, A. A. & Augusti, R. On-surface multicomponent Povarov reaction examined by paper spray mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 472, 116775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijms.2021.116775 (2022).

Liu, M. et al. Heterogeneous synthesis of tetrahydroquinoline derivatives via cascade Povarov reaction catalyzed by sulfonic acid functionalized metal–organic frameworks. Nano Select 2, 1968–1973. https://doi.org/10.1002/nano.202100033 (2021).

Reyes-Gutiérrez, P. E. et al. Helquats as promoters of the Povarov reaction: Synthesis of 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline scaffolds catalyzed by helicene-viologen hybrids. ChemPlusChem 85, 2212–2218. https://doi.org/10.1002/cplu.202000151 (2020).

Park, D. Y., Hwang, J. Y. & Kang, E. J. Fe(III)-catalyzed oxidative Povarov reaction with molecular oxygen oxidant. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 42, 798–801. https://doi.org/10.1002/bkcs.12273 (2021).

Mo, N.-F., Zhang, Y. & Guan, Z.-H. Highly enantioselective three-component Povarov reaction for direct construction of azaspirocycles. Org. Lett. 24, 6397–6401. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.orglett.2c02421 (2022).

Chen, J.-M. et al. Iron-catalyzed divergent approach to naphthyridinones and quinolinones: Leveraging Povarov and carbonyl-alkyne metathesis reactions of electron deficient alkynes. Org. Chem. Front. 10, 5505–5511. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3QO01302B (2023).

Yasukawa, T., Yang, X., Yamashita, Y. & Kobayashi, S. Development of metal-free, trifluoromethanesulfonic acid-immobilized nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts for povarov reactions. J. Org. Chem. 87, 16157–16164. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.joc.2c01210 (2022).

Shamsa, F., Motavalizadehkakhky, A., Zhiani, R., Mehrzad, J. & Hosseiny, M. S. ZnO nanoparticles supported on dendritic fibrous nanosilica as efficient catalysts for the one-pot synthesis of quinazoline-2,4(1H,3H)-diones. RSC Adv. 11, 37103–37111. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1RA07197A (2021).

Beheshti, S., Motavalizadehkakhky, A., Zhiani, R., Nouri, S. M. M. & Zahedi, E. Palladium doped PDA-coated hercynite as a highly efficient catalyst for mild hydrogenation of nitroareness. Sci. Rep. 14, 11969. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62226-5 (2024).

Edalatian Tavakoli, S., Motavalizadehkakhky, A., Homayouni Tabrizi, M., Mehrzad, J. & Zhiani, R. Study of the anti-cancer activity of a mesoporous silica nanoparticle surface coated with polydopamine loaded with umbelliprenin. Sci. Rep. 14, 11450. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62409-0 (2024).

Ghabdian, K., Motavalizadehkakhky, A., Zhiani, R., Allahresani, A. & Ghabdian, M. Cu(II) salen complex grafted onto KCC-1 as a convenient multifunctional heterogeneous catalyst for the preparation of 4H-benzochromenes. Res. Chem. Intermed. 50, 3179–3196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11164-024-05311-8 (2024).

Sharafkhani, J., Zhiani, R., Motavalizadehkakhky, A., Mehrzad, J. & Sadeghzadeh, S. M. Green synthesis of Nd2Sn2O7 nanostructures using gum of ferula assa-feotida for the fabrication of 3a,4-dihydronaphtho[2,3-c]furan-1(3H)-one. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 44, 1669–1681. https://doi.org/10.1080/10406638.2023.2202864 (2024).

Yue, B., Hu, Q., Ji, L., Wang, Y. & Liu, J. Facile synthesis of perovskite CeMnO3 nanofibers as an anode material for high performance lithium-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 9, 38271–38279. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9RA07660C (2019).

Wu, X. et al. Synthesis and adsorption properties of halloysite/carbon nanocomposites and halloysite-derived carbon nanotubes. Appl. Clay Sci. 119, 284–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2015.10.029 (2016).

Daou, I. et al. Probing the dehydroxylation of kaolinite and halloysite by in situ high temperature X-ray diffraction. Minerals 10, 1 (2020).

Phokha, S., Pinitsoontorn, S., Chirawatkul, P., Poo-arporn, Y. & Maensiri, S. Synthesis, characterization, and magnetic properties of monodisperse CeO2 nanospheres prepared by PVP-assisted hydrothermal method. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 7, 425. https://doi.org/10.1186/1556-276X-7-425 (2012).

Nilchi, A., Yaftian, M., Aboulhasanlo, G. & Rasouli Garmarodi, S. Adsorption of selected ions on hydrous cerium oxide. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 279, 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-007-7255-3 (2009).

Kang, X., Csetenyi, L. & Gadd, G. M. Fungal biorecovery of cerium as oxalate and carbonate biominerals. Fungal Biol. 127, 1187–1197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.funbio.2022.07.006 (2023).

Sharif, S., Sahin, O., Khan, I. U. & Büyükgüngör, O. 1-D and 2-D coordination polymers of cerium(III) with pyridine-2,4,6-tricarboxylic acid: Synthesis and structural, spectroscopic, and thermal properties. J. Coord. Chem. 65, 1892–1904. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958972.2012.685165 (2012).

Oh-e, M. & Nagasawa, A. Interactions between hydrated cerium(III) cations and carboxylates in an aqueous solution: Anomalously strong complex formation with diglycolate, suggesting a chelate effect. ACS Omega 5, 31880–31890. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.0c04724 (2020).

Zhao, Y. et al. Ln-MOFs with window-shaped channels based on triazine tricarboxylic acid as a linker for the highly efficient capture of cationic dyes and iodine. Inorg. Chem. Front. 8, 1736–1746. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0QI01279C (2021).

Koç, Z. E. Complexes of iron(III) and chromium(III) salen and salophen Schiff bases with bridging 1,3,5-triazine derived multidirectional ligands. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 48, 769–775. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhet.577 (2011).

Bartoli, G. et al. Cerium (III) triflate versus cerium (III) chloride: Anion dependence of Lewis acid behavior in the deprotection of PMB ethers. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 2176–2180 (2004).

Hayano, T. et al. Novel cerium(III)–(R)-BNP complex as a storable chiral Lewis acid catalyst for the enantioselective hetero-Diels–Alder reaction. Chem. Lett. 32, 608–609. https://doi.org/10.1246/cl.2003.608 (2003).

Yang, G.-P., Shang, S.-X., Yu, B. & Hu, C.-W. Ce(III)-containing tungstotellurate(VI) with a sandwich structure: An efficient Lewis acid–base catalyst for the condensation cyclization of 1,3-diketones with hydrazines/hydrazides or diamines. Inorg. Chem. Front. 5, 2472–2477. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8QI00678D (2018).

Dagar, N., Singh, S. & Raha Roy, S. Synergistic effect of cerium in dual photoinduced ligand-to-metal charge transfer and Lewis acid catalysis: Diastereoselective alkylation of coumarins. J. Org. Chem. 87, 8970–8982 (2022).

Ghesti, G. F., de Macedo, J. L., Parente, V. C. I., Dias, J. A. & Dias, S. C. L. Synthesis, characterization and reactivity of Lewis acid/surfactant cerium trisdodecylsulfate catalyst for transesterification and esterification reactions. Appl. Catal. A 355, 139–147 (2009).

Bartoli, G. et al. SiO2-supported CeCl3·7H2O−NaI Lewis acid promoter: Investigation into the Garcia Gonzalez reaction in solvent-free conditions. J. Org. Chem. 72, 6029–6036. https://doi.org/10.1021/jo070384c (2007).

Kerr, R. W. F. et al. Ultrarapid cerium(III)–NHC catalysts for high molar mass cyclic polylactide. ACS Catal. 11, 1563–1569. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.0c04858 (2021).

Bartoli, G. et al. Microwave-assisted cerium(III)-promoted cyclization of propargyl amides to polysubstituted oxazole derivatives. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 630. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejoc.201101302 (2012).

Zuo, Y., Su, Z., Wang, J. & Hu, C. Theoretical study on the mechanism and selectivity of asymmetric cycloaddition reactions of 3-vinylindole catalyzed by chiral N, N’-dioxide-Ni(II) complex. Catal. Today 298, 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2017.05.042 (2017).

Fochi, M., Caruana, L. & Bernardi, L. Catalytic asymmetric aza-Diels–Alder reactions: The Povarov cycloaddition reaction. Synthesis 46, 135–157 (2014).

He, L., Bekkaye, M., Retailleau, P. & Masson, G. Chiral phosphoric acid catalyzed inverse-electron-demand Aza-Diels–Alder reaction of isoeugenol derivatives. Org. Lett. 14, 3158–3161. https://doi.org/10.1021/ol301251h (2012).

Akiyama, T., Morita, H. & Fuchibe, K. Chiral Brønsted acid-catalyzed inverse electron-demand Aza Diels−Alder reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 13070–13071. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja064676r (2006).

Loncaric, C., Manabe, K. & Kobayashi, S. AgOTf-catalyzed Aza-Diels–Alder reactions of Danishefsky’s diene with imines in water. Adv. Synth. Catal. 345, 475–477. https://doi.org/10.1002/adsc.200390052 (2003).

Powell, D. A. & Batey, R. A. Lanthanide(III)-catalyzed multi-component aza-Diels–Alder reaction of aliphatic N-arylaldimines with cyclopentadiene. Tetrahedron Lett. 44, 7569–7573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tetlet.2003.08.066 (2003).

Kollmann, J. et al. A simple ketone as an efficient metal-free catalyst for visible-light-mediated Diels–Alder and aza-Diels–Alder reactions. Green Chem. 21, 1916–1920. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9GC00485H (2019).

Xing, X., Wu, J. & Dai, W.-M. Acid-mediated three-component aza-Diels–Alder reactions of 2-aminophenols under controlled microwave heating for synthesis of highly functionalized tetrahydroquinolines. Part 9: Chemistry of aminophenols. Tetrahedron 62, 11200–11206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2006.09.012 (2006).

Acknowledgements

The Neyshabur Branch, Islamic Azad University, Neyshabur, Iran, provided the facilities for this study, which are gratefully acknowledged by the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AH prepared, analyzed and synthesized the catalyst and product, wrote the article. AM was the supervisor of this research during the time of experiment and writing the article. RZ participated in research and writing. SMMN participated in research and writing. EZ participated in research and writing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hosseini, A., Motavalizadehkakhky, A., Zhiani, R. et al. Cerium(III) immobilized on the functionalized halloysite as a highly efficient catalyst for aza-Diels–Alder reaction. Sci Rep 14, 29772 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76775-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76775-2