Abstract

Psoriasis, being a chronic, inflammatory, lifelong skin disorder, has become a major threat to the human population. The precise and effective diagnosis of psoriasis continues to be difficult for clinicians due to its varied nature. In northern India, the prevalence of psoriasis among adult population ranges from 0.44 to 2.8%. Chronic plaque psoriasis accounts for over 90% of cases. This study utilized a dataset of 325 raw images collected from a reputable local hospital using a digital camera under uniform lighting conditions. These images were processed to generate 496 image patches (both diseased and normal), which were then normalized and resized for model training. An automated psoriasis image recognition framework was developed using four state-of-the-art deep transfer learning models: VGG16, VGG19, MobileNetV1, and ResNet-50. The convolutional layers adopted various edge, shape, and color filters to generate the feature map for psoriasis detection. Each pre-trained model was adapted with two dense layers, one dropout layer, and one output layer to classify input images. Among these models, MobileNetV1 achieved the best performance, with 94.84% sensitivity, 89.37% specificity, and 97.24% overall accuracy. Hyper-parameter tuning was performed using grid search to optimize learning rates, batch sizes, and dropout rates. The AdaGrad (Adaptive gradient)) optimizer was chosen for its adaptive learning rate capabilities, facilitating quicker convergence in model performance. Consequently, the methodology’s performance improved to 94.25% sensitivity, 96.42% specificity, and 99.13% overall accuracy. The model’s performance was also compared with non-machine learning-based diagnostic methods, yielding a Dice coefficient of 0.98. However, the model’s effectiveness is dependent upon high-quality input images, as poor image conditions may affect accuracy, and it may not generalize well across diverse demographics or psoriasis variations, highlighting the need for varied training datasets for robustness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Psoriasis, usually characterized by rapid skin cell buildup, manifests as red patches with white scales. In fact, this disease is a major threat to human health due to varied chronic conditions, higher prevalence rate, increased mental depression and anxiety, treatment challenges, etc. Dermatologists face diagnostic challenges due to variability and subjectivity, hindering efficient clinical practice. Its prevalence rate ranges from 0.91 to 8.5% in adults and 0.0–2.1% amongst children1. Global prevalence is around 2–3% of world’s population, according to the world psoriasis day consortium2. In northern India, the prevalence rate of psoriasis amongst adults varies from 0.44 to 2.8%. A comprehensive study conducted across various medical institutions in Dibrugarh, Calcutta, Patna, Darbhanga, Lucknow, New Delhi, and Amritsar revealed that the overall incidence of psoriasis among skin patients is 1.02%, with observed rates ranging from 0.44 to 2.2%3. Chronic plaque psoriasis is the most prevalent form of the disease, accounting for over 90% of cases worldwide4. In 2016, psoriasis was associated with an estimated 5.6 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), which is at least three times higher than that of inflammatory bowel disease, according to the Global Burden of Disease Study5. Most prevalence data stems from hospital-based research, with a lack of large-scale population studies to accurately assess the community prevalence of this condition6,7,8,9. Artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled image recognition presents a promising solution for automating diagnostics and improving clinical efficiency. Psoriasis has several treatments available, however there is currently no known cure for the condition, effective management improves patients’ quality of life, especially at early stages. AI has transformed multiple fields by integrating human-like capabilities such as learning and reasoning into software systems, enabling computers to perform tasks typically executed by humans. Advances in computing power, extensive datasets, and innovative AI algorithms special deep transfer learning models enhanced the scopes of biomedical image-guided problem solving in areas like finger vein recognition10, diabetic retinopathy detection11,12,13, lung nodule identification14, RNA engineering15,16, bio-mathematical challenges17, smart agriculture18, and various cancer detection (viz., skin, breast and prostate)19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27 etc.

The integration of AI in clinical settings raises important ethical aspects, particularly concerning patient privacy, data security, and potential biases in diagnostics. Protecting patient confidentiality necessitates stringent data protection measures to prevent unauthorized access, while robust security protocols are essential for safeguarding sensitive health information. Additionally, AI models can inherit biases from their training data, potentially resulting in disparities in healthcare delivery; ensuring diverse and representative datasets can help address these issues. It is vital to connect the technical performance of AI models with their clinical impact, illustrating how improved diagnostic accuracy and efficiency can enhance patient outcomes, streamline clinical processes, and assist healthcare providers in making informed decisions.

Deep learning (DL) has shown exceptional success in analyzing various image types—such as magnetic resonance images, optical images, digital images, and dermoscopic images—enabling effective prediction and classification of a range of disorders, including diabetic retinopathy, cancer, cardiac arrest, breast cancer, brain tumors, and fatty liver disease28,29,30. Leveraging digital image processing and machine learning techniques, researchers implemented automated disease detection under low-resource computational frameworks11,31. Studies on psoriasis detection have explored various approaches, including transfer learning models and support vector machines (SVM), achieving accuracies of 92.2% and 90%, respectively32,33. Researchers also utilized the capabilities of DL, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) models, to achieve notable accuracies of 84.2% and 72.3% in classifying various types of psoriasis34. DL models have further been instrumental in automated psoriasis diagnosis, showcasing promising accuracy in multiple investigations35,36,37,38,39,40. An AI-based dermatology diagnostic assistant, powered by the EfficientNet-B4 algorithm, exhibited an impressive overall accuracy of 95.80%, in addressing both two-class and four-class psoriasis classification problems41,42. Nieniewski et al. (2023) demonstrated transfer learning models with SVM-RBF classifiers with an accuracy of 80.08% for detecting psoriasis43. Another notable implementation of a smart-assisted psoriasis identification system was employed CNN models to achieve an outstanding accuracy of 98.1%44. Fink et al. (2018)45 adopted intra-class-correlation-coefficients (ICCCs) and mean absolute difference (MAD), achieving a mean ICCC of 0.877 and MAD of 2.2. Additionally, Raj et al. (2021)46proposed a transfer learning model for psoriasis segmentation, resulting in Dice-Coefficient and Jaccard scores of 97.43% and 96.05% respectively. Hsieh et al. (2022) introduced a nail psoriasis severity index utilizing the mask R-CNN architecture47, while Shrivastava et al. (2016) developed a computer-aided system for psoriasis detection using principal component analysis with 540 aggregated images48. Furthermore, Shtanko et al. (2022)49 developed a CNN architecture using the Dermnetdataset, achieving 98% prediction accuracy in psoriasis detection with respect to other skin diseases. A clinical decision support system was developed using DL model specifically to psoriasis treatment strategies50. Okamoto et al. (2022) utilized a customized dataset for psoriasis severity analysis with a transfer learning model51. In addition, the severity of psoriasis was evaluated using dictionary learning and cascaded deep learning methods based on skin images52,53,54,55,56. Table 1 summarized the literature describing DL models for psoriasis recognition.

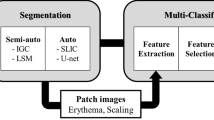

According to the literature, it can be observed that automated detection of psoriasis still remains a challenging task. Its varied nature manifests with different types viz., plaque, guttate, inverse, pustular and erythrodermic psoriasis etc., that affect human population physically and mentally both. This work aimed at developing an efficient deep transfer leaning framework for screening of psoriatic infection with more accuracy over the existing studies, where the patch-based image selection from the raw clinical photographs improved the model efficiency. Literature survey revealed that transfer learning models were found to efficiently implement in many of the automated disease detection processes with higher accuracy. This work focused on employing an efficient framework for psoriasis screening using standard deep transfer learning models viz., VGG-16, VGG-19, ResNet-50, and MobileNetV1. It is well known that training of these models requires large number of images, but the availability of real diagnostic and annotated images is a challenging task. Under such circumstances, our proposed framework included patch-generation module to generate more sub-images from raw images prior for efficient training. Moreover, such module enabled the pre-trained models to capture finer information about the infection, which may be missed during image sampling. The technical contribution can be thought of exploring adaptive moment (Adam) and adaptive gradient (AdaGrad) optimizers for hyperparameter tuning for psoriasis detection, aiming to achieve the best possible model performance. The performance of these transfer learning models was evaluated and compared in respect to sensitivity, specificity and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve.

Proposed methodology

Image acquisition

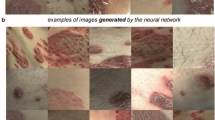

Under the guidance of the dermatologist, a customized digital image dataset was developed by capturing 175 photos of psoriasis diseased skin and 150 images of healthy skin at a reputable state hospital in West Bengal, India. The digital photos of human skins were captured following relevant guidelines and regulations as per Institutional ethical approval [Ref. No. 09/IEC/RNLKWC/2024; Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC)/Institutional Review Board (IRB), Raja Narendralal Khan Women’s College (Autonomous), Midnapur – 7210102, India] and no human samples (tissue / serum) were used in this study. Informed consent was obtained from all the participating subjects. The original images were saved in JPEG format, each with dimensions of 2532 × 1170 pixels (see Fig. 1). A digital single-lens mobile camera was utilized to capture high-resolution human skin images. These images exclusively focus on facial skin, taken under the illuminating fluorescence light source. Our dataset comprises of a total of 60 subjects, ranging in age from 20 to 45 years old. Given the nature of dermatological conditions such as psoriasis, we encountered significant variability in the raw images. This variability includes background noise, portions of normal skin, and blurry areas, especially in the context of the region of interest, which is the psoriasis-affected skin. To optimize the image data used for training transfer learning models, a meticulous process of image preparation was undertaken (such as patch creation, resizing and scaling etc.). We made a deliberate choice to focus on picture patches that contain only the signatures of psoriasis [class I] and healthy skin [class II] (see Fig. 2). This approach allows our models to concentrate on the key features of interest while filtering out irrelevant noise and distractions.

Using the image patches, the proposed methodology predicting psoriasis disease has been graphically described in the above figure.

Image preprocessing

-

A)

Resizing image.

One of the key tasks of pre-processing for transfer learning involves resizing images. This step involves adjusting the dimensions of the input images to fit the specific requirements of the chosen transfer learning models (VGG16, VGG19, MobileNetV1, ResNet-50). These models have been pre-trained on datasets (ImageNet) where images are of size 224 × 224 pixels with 3 color channels (red, green, blue). So, the selected patch images were resized from approximately 240 × 240 × 3 to 224 × 224 × 3 pixels for compatibility of the model. This ensures consistency in input dimensions across all images, making it easier for the model to learn patterns and features.

-

B)

Normalizing pixel values.

Normalization involves adjusting the pixel values of the images. Pixel values in images typically range from 0 to 255 (8-bit representation), with 0 being black and 255 being white. Normalization standardizes these values to a range between 0 and 1. Each pixel value in the image matrix is divided by 255. This operation scales down the pixel values so they fall within the range of 0 to 1.

-

C)

Encoding labels into binary format (1s and 0s).

This step involves transforming categorical labels into a numerical format suitable for training transfer learning models. First, we identify the unique categories in the provided labels. We then assign a binary representation to each unique category. Each original label is then converted into a binary vector based on its binary representation. The resulting binary vectors serve as the ground truth labels during model training. For instance, when the model predicts an image, it outputs a vector of probabilities for each class. This vector is then compared to the ground truth binary label vector using a loss function like categorical cross-entropy to update the model’s weights during training.

Psoriasis screening using transfer learning

Transfer learning adapts for new tasks, leveraging knowledge from one task for another. It’s like training a model basic ability before honing it for a particular task, which saves time and frequently yields better results, especially when there is shortage of data. Four popular pre-trained models (VGG16, VGG19, MobileNetV1, ResNet-50) were used for psoriasis diagnosis. The VGG16 and VGG19 models are renowned for their simplicity, elegance, and exceptional performance in image classification tasks. These were developed by the Visual Geometry Group (VGG) at the University of Oxford. These models stand out for their deep design, which includes 16 or 19 weight layers, depending on the model. Each layer uses 3 × 3 convolutional filters, and a 2 × 2 max-pooling layer comes after it. These models were able to capture complex information in pictures while retaining a consistent architecture because to the use of tiny convolutional filters, which makes them simpler to comprehend and train.

MobileNetV1 is unique in that it emphasizes low memory use and model efficacy. This is accomplished by using depthwise separable convolutions, which significantly lower the network’s parameter count while maintaining competitive accuracy. In response to the growing need for efficient deep neural networks that can run on low-resource devices, such smartphones, Google developed MobileNet. We have used the V1 version of this specific MobileNet architecture.

ResNet-50 introduced the idea of residual blocks, where shortcut connections omit one or more levels and contains 50 layers. The training of very deep networks is facilitated by this skip-connection design. Microsoft Research created ResNets to solve the vanishing gradient issue in extremely deep networks. ResNet-50 has achieved records on several benchmark datasets, including ImageNet, and performs superbly in image classification tasks.

After running all these models in the context of psoriasis detection, we observed that MobileNetV1 used to perform better as compared to other transfer learning models. Apart from the performance matrix, MobileNetV1 was found to be the lightest and simple algorithm due to its ability to perform efficiently under low computing resource-based framework. The proposed methodology has been depicted in the below flowchart (see Fig. 3).

Proposed architecture

-

A)

MobileNetV1 framework.

MobileNetV1 model, architecture reviewed by google with the application of depth wise separable convolution layer the model was able reduce the size and complexity compared to the other state of the art models. In these depth wise separable layers, a depthwise convolution and a pointwise convolution were used. Based on these two operations the cost function became

A width multiplier (α) was introduced to control the number of channels in depth wise convolutional cost. A detailed summary of Eqs. (1 & 2) notations with their interpretations were given in the Table 2.

Now the cost function was updated (\(\:{D}_{k}\times\:\:{D}_{k}\times\:\alpha\:M\times\:\:{D}_{F}\times\:\:{D}_{F}+\alpha\:M\times\:\alpha\:N\times\:\:{D}_{F}\times\:\:{D}_{F})\) where range of α lies between 0 and 1. After a width multiplier a resolution multiplier was also added to control the input image resolution of the network so, the final version of the cost function came as follows.

Here ρ value lies in the range of 0 to 1. The develop cost function makes the main difference between MobileNetV1 and other architectures in context to the diagnostic classification. The proposed architecture, designed for 3-channel color skin images (RGB), utilized 224 × 224 image-patches as input. The initial segment included a standard convolutional layer with 32 filters, followed by batch normalization and ReLU activation to address the vanishing gradient problem, maintaining spatial dimensions at 112 × 112 × 32. The second part focused on depthwise separable convolutional layers (see Eqs. 1&2), enhancing feature mapping capacity with 288 and 2048 parameters. This pattern was repeated with zero-padding layers for feature extraction. The last output layer of the MobileNetV1 model was removed, an extra set layer had been added to make the model more accurate in the following task. After getting the output from the last depthwise separable convolutional layer a flatten layer was used to convert the 3D output to 1D array input. Next a dense layer with ReLU activation was included to learn complex patterns in the data. One dropout layer was also added to counter the overfitting scenario by reducing the reliance on specific neurons. Lastly an output layer with a single neuron and a sigmoid activation function was added to make the final classification. For visual understanding and detailed architecture of the proposed methodology using MobileNetV1 model, graphical and tabular representations in Fig. 4; Table 3 respectively.

The pseudo code of proposed architecture was given below:

-

B)

Hyperparameter tuning.

In order to minimize the loss function, which was determined using binary cross-entropy, two optimizers and a learning rate were taken into consideration throughout the MobileNetV1 model’s parameter tweaking process. Due to the improvement in performance shown in the training and testing process compared to the other models, we decided to modify the parameters of the MobileNetV1.

Learning rate

It establishes the extent to which the model changes throughout training. A low learning rate might result in a lengthy training process or a local minimum, whereas a high learning rate could force the model to skip optimum solutions. In our case, we take a learning rate in the range [0.0001, 0.001] to test the model on different learning thresholds57. To enhance its performance, or, to put it another way, to boost its accuracy, we have slightly altered its parameters. Table 3 includes the fine-tuned version’s architecture in detail, and Fig. 5 represents the selection of the learning rate for our model.

Optimization functions

In the process of parameter tweaking the MobileNetV1 model, we explore four different optimizers (SGD, SGD with moments, Adam, AdaGrad). Among them, two optimizers, viz., adaptive moment (Adam) with a leaning rate of [0.0001, 0.001] and adaptive gradient (AdaGrad) with an auto-selected leaning rate, were found to minimize the loss, computed by the binary cross-entropy function. It automatically selected the learning rate of the layers and optimized the model’s performance accordingly. This specific optimizer, which has previously been explored in this area of medical image analysis, performed well in the task of classification40,58. Hence, the governing Eqs. (3–7) of the loss function and optimizers were mathematically represented below.

Suppose we have total ‘n’ no. of samples where \(y_i\) and \({\widehat y}_i\) denote the actual and predicted outputs. Then, the loss due to the training of the network is computed by binary cross-entropy function as

Now the following optimizers were used as follows:

-

(a)

Adaptive moment estimation (known as Adam).

where \(\:\frac{\delta\:L\left({y}_{i},{\widehat{y}}_{i}\right)}{\partial\:{w}_{t}}\) denoted gradient at loss function.

-

(b)

Adaptive Gradient Algorithm (known as AdaGrad).

To automatically assign the learning rate, an advanced optimizer was adopted with an expectation to provide better performance in classification task.

Where \(\:\frac{\delta\:L\left({y}_{i},{\widehat{y}}_{i}\right)}{\partial\:{w}_{t}}\) signifies the gradient of the loss function with respect to the parameters at the current time step t.

-

(c)

Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD).

SGD optimizer is a variant of gradient descent algorithm, which uses one or a small number of training instances at a time to update the model parameters more frequently than batch gradient descent.

Where \(\:{\theta\:}_{t}\), \(\:\eta\:\) and \(\:{\nabla\:}_{\theta\:}L\left({\theta\:}_{t}\right)\) indicate the model parameters at ‘t’ iteration, learning rate, and the gradient (partial derivative) of the loss function L(θ) respectively.

-

(d)

Stochastic Gradient Descent with Moments.

The formula was updated for SGD with momentum, introduced a velocity term, which turns into a running average of past gradients to maintain the direction of optimization.

where \(\:{\theta\:}_{t}\) model parameters (weights) at iteration t., \(\:\eta\:\): Learning rate, a small constant that controls the step size of the update, \(\:{\nabla\:}_{\theta\:}L\left({\theta\:}_{t}\right)\): Gradient (partial derivative) of the loss function L(θ) with respect to parameters \(\:{\theta\:}_{t}\), \(\:{v}_{t}\): Velocity or momentum term at iteration t, which accumulates the previous gradients, \(\:\gamma\:\): Momentum coefficient.

-

E) Performance metric

Recall/Sensitivity

The capacity of a model to accurately identify all positive instances within a dataset is measured by recall, also known as true positive rate or sensitivity. It determines the proportion of genuine positives to all real positives. High recall means the model captures the majority of positive examples, which is crucial because missing a positive instance might have serious repercussions.

where TP- True positive; FN- False negative.

Specificity

Specificity is a statistic that measures how well a model can recognize real negatives among all other possible negatives. It determines the proportion of real negatives to all real negatives.

where TN- True negative; FP- False positive.

Precision

In the context of a classification system, precision measures the percentage of correctly identified positive items compared to the total number of objects categorized as positive. It illustrates how well the model predicts positive events and reduces the likelihood that negative events will be mistaken for positive ones. The number of true positive findings divided by the total of true positive and false positive results is the formula used to calculate precision. It draws attention to how trustworthy a model’s positive predictions are, which is crucial in situations where misclassifying negatives as positives might have serious repercussions.

Accuracy

Accuracy is defined as the proportion of correctly predicted instances (including true positives and true negatives) to all occurrences in the dataset. It is a frequently employed indicator for assessing a classification model’s performance.

Where TP- True positive; TN- True negative; FP- False positive; FN- False negative.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC)

The performance of a model at various discriminating thresholds is depicted graphically by the ROC curve. At various threshold values, it shows the true positive rate (sensitivity) versus the false positive rate (1 - specificity). The model’s overall performance is summarized by the area under the ROC curve (AUC), with a greater AUC denoting better discrimination between positive and negative cases.

Dice coefficient

A statistical method for determining how similar two samples are is the dice coefficient, sometimes called the dice similarity coefficient (DSC). When a confusion matrix is used for classification tasks, particularly when dealing with binary classification or picture segmentation issues. To compare the MobileNetV1 performance with a non-ML base diagnostic method (i.e., clinician’s decision), the dice coefficient was obtained using the following formula.

Results and discussion

Computational setup

The proposed skin disease recognition model underwent experiments using two systems: PC (8GB memory, 2GB GPU) for image pre-processing and Google Colab (12.69 GB RAM, 15 GB GPU) for model fitting and validation.

Psoriasis image-patch processing and classification

The skin images were initially processed into 240\(\:\times\:\)240 patches, resulting in 497 patches representing psoriasis and 396 patches of healthy skin. These patches were then resized to 224\(\:\times\:\)224 pixels to fit the requirements of pre-trained convolutional neural network models, specifically VGG16, VGG19, ResNet-50, and MobileNetV1. Each of these models was trained using 80% of the data, aiming to fine-tune the models for skin lesion classification. Amongst these, MobileNetV1 model was found to perform better over other models to distinguish between psoriasis and healthy skin patches. Furthermore, the model fine-tuned with the Adam and AdaGard optimizers led to improve the model’s performance (using Eqs. 8–11). Delving into the architecture of MobileNetV1 used in this study, it can be noted that the model was structured with specific layer groupings for different levels of feature map generation. The first 37 layers filters were responsible for generating low-level feature maps, capturing basic patterns and textures in the input image patches. Following this, layers filters 38 to 75 were designed to extract mid-level features, such as more complex shapes and structures within the skin lesions. Lastly, layers filters 76 to 86 focused on high-level feature extraction, capturing intricate details and unique characteristics specific to psoriasis lesions. A sample of feature map of the different layers was given below in Fig. 6.

In the classification module of the proposed architecture, we experimentally adopted four optimizers using Eqs. (4–7) for minimizing the loss function using Eq. (3). From Table 4, it can be observed that the among all the optimizer AdaGrad optimizer provided the maximum accuracy as compared to the other optimizers.

Accordingly, the MobileNetV1 model fine-tuned with AdaGrad optimizer and other hyper-parameters was found to achieve overall accuracy of 99.13%. In Table 5, the performance of the proposed methodology was compared to the state-of-the-art models, as given below.

In Table 5, it can be observed that the fine-tuned MobileNetV1-based methodology achieved 94.25% sensitivity, 96.42% specificity, and 99.13% accuracy, respectively. Therefore, the achieved sensitivity of 94.25% indicated the model’s ability to correctly identify a true positive case of psoriasis from the dataset. The specificity of 96.42% signifies the model’s ability to accurately identify true negative cases of healthy skin.

Figure 7 presents the performance matrix as a heatmap for a better understanding of the proposed methodology. The model accuracy of 99.13% represents the percentage of correct classification of both psoriasis and healthy skin patches. In this context, a ROC graph was provided below in Fig. 8 to compare the performance of the state-of-the-art models with the proposed methodology graphically.

In addition to the quantitative performance evaluation, the proposed fine-tuned MobileNetV1 model’s efficiency was assessed based on medical expert’s opinion using Eq. (12), as follows:

where the DC value (= 0.98) demonstrates very close agreement between the medical expert’s diagnostic decision and the predicted outcome of our proposed model. Therefore, it can be thought of as a reliable AI-assisted tool for practical implementation at least where there is a scarcity of specialized clinicians.

In Table 6, the methodology proposed, dataset used, and accuracy achieved by the state-of-the-art literatures were summarized and compared with our proposed fine-tuned transfer learning methodology towards psoriasis disease detection. So, it can be well observed that the proposed model achieved significant accuracy for screening psoriasis from a healthy skin image. As the model required a large number of psoriasis images for training purposes, primarily, an image augmentation process in terms of image-patch generation was followed from raw psoriasis images that included resizing all patches into 224 × 224 pixels. Further, the pixel values were normalized into the range [0, 1], which improved the classification task by ensuring consistent input image dimensions and enhancing model compatibility. Such image augmentation impacted the model performance to achieve higher accuracy, from 88 to 96%, as visualized in the ROC plot (see Fig. 10).

At the same time, the runtime complexities of the transfer learning models were computed and compared with respect to the system configuration, as mentioned below in Table 7. It can be observed that VGG16 has a runtime of 42.75 s and an accuracy of 89.43, while its more advanced counterpart, VGG19, takes slightly longer at 43.64 s, yielding an improved accuracy of 90.67. MobileNetV1 demonstrates a significant performa nce leap, running in 41.17 s with an accuracy of 97.24. ResNet-50 is the fastest among the conventional models, with a runtime of 28.27 s, but it falls short in performance with an accuracy of 86.96.

The standout performer is the proposed MobileNetV1 model, which not only achieves a superior runtime of 28.12 s but also delivers an impressive accuracy of 98.02. An additional configuration of this proposed model pushes the accuracy even higher to 99.13, with a runtime of 28.18 s. Among all the models, the proposed MobileNetV1 is the best due to its optimal balance of speed and performance. It not only demonstrates the shortest runtime but also achieves the highest accuracy, indicating exceptional efficiency and accuracy in classification tasks. This makes it the most suitable model for real-time applications where both quick processing and high accuracy are crucial.

The proposed MobileNetV1 utilized depthwise separable convolutions, which split the standard convolution operation into depthwise and pointwise convolutions. This design significantly reduces the number of parameters and the computational load. The lower number of parameters made the proposed framework suitable for deployment on mobile and edge devices with limited computational resources. Though it requires more runtime than ResNet-50, the accuracy of the MobileNetV1 bits of every other model of the study, along with ResNet-50.

Conclusion

This work proposed a fine-tuned transfer learning model (MobileNetV1) for automated detection of psoriasis disease using normal optical images of human skin. Though this proposed methodology achieved the maximum accuracy, this study has some limitations: (a) patch selection from raw images by the experienced medical expert guided; (b) unavailability of the large dataset. The model’s performance is highly dependent on the quality of the input images, poor lighting, low resolution, or obstructions can negatively impact accuracy. (c) The model may not generalize well to all patient demographics or variations in psoriasis presentation. Training on diverse datasets is essential to improve its robustness.

The proposed MobileNetV1 model, optimized for hyper-parameter tuning, demonstrates superior performance in psoriasis detection, achieving a remarkable 99.13% accuracy and a runtime of 28.18 s. This efficiency makes it ideal for real-time clinical use. The model can be integrated into dermatology clinics to enhance diagnostic accuracy, reduce healthcare professionals’ workload, and support telemedicine, improving access to dermatological care for remote patients. Additionally, it aids in personalized treatment planning, disease monitoring, and large-scale data analysis, offering potential applications for other skin conditions and contributing to research on new treatments.

Data availability

This paper analyses the images as secondary data collected the local government hospital repository : https://github.com/Sumit-Nayek/Psoriasis_Data.

References

Parisi, R., Symmons, D. P., Griffiths, C. E. & Ashcroft, D. M. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J. Invest. Dermatol. 133 (2), 377–385. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2012.339 (2013).

Egeberg, A., Andersen, Y. M. F. & Thyssen, J. P. Prevalence and characteristics of psoriasis in Denmark: findings from the Danish skin cohort. BMJ Open. 9 (3), e028116. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028116 (2019).

Okhandiar, R. P., & Banerjee, B. N. Psoriasis in the tropics: An epidemiological survey. J. Indian Med. Assoc. 41 (1), 16–20 (1963).

Dogra, S. & Mahajan, R. Psoriasis: Epidemiology, clinical features, co-morbidities, and clinical scoring. Indian Dermatology Online J. 7 (6), 471–480. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5178.193906 (2016).

Raharja, A., Mahil, S. K., Barker, J. N. & London Psoriasis: a brief overview. Clinical medicine (England), 21 (3), 170–173. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmed.2021-0257 (2021).

Lomholt, G. Prevalence of skin diseases in a population; a census study from the Faroe Islands. Dan. Med. Bull. 11, 1–7 (1964).

Hellgren, L. Psoriasis: The prevalence in sex, age, and occupational groups in the total population in Sweden. Morphology, inheritance, and association with other skin and rheumatic diseases. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 47 (Suppl. 47), 1–59 (1967).

Brandrup, F. & Green, A. The prevalence of psoriasis in Denmark. Acta dermato-venereologica. 61 (4), 344–346 (1981).

Farber, E. M. & Nall, L. The natural history of psoriasis in 5,600 patients. Dermatology. 148 (1), 1–18 (1974).

Bilal, A., Sun, G. & Mazhar, S. Finger-vein recognition using a novel enhancement method with convolutional neural network. J. Chin. Inst. Eng. 44 (5), 407–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/02533839.2021.1919561 (2021).

Bilal, A. et al. Improved support Vector Machine based on CNN-SVD for vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy detection and classification. PloS ONE. 19 (1), e0295951. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0295951 (2024).

Bilal, A., Liu, X., Shafiq, M., Ahmed, Z. & Long, H. NIMEQ-SACNet: a novel self-attention precision medicine model for vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy using image data. Comput. Biol. Med. 171, 108099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.108099 (2024).

Bilal, A., Zhu, L., Deng, A., Lu, H. & Wu, N. AI-Based automatic detection and classification of Diabetic Retinopathy using U-Net and deep learning. Symmetry. 14 (7), 1427. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym14071427 (2022).

Bilal, A. et al. IGWO-IVNet3: DL-Based automatic diagnosis of lung nodules using an Improved Gray Wolf optimization and InceptionNet-V3. Sensors. 22 (24), 9603. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22249603 (2022).

Feng, X. et al. January, Advancing single-cell RNA-seq data analysis through the fusion of multi-layer perceptron and graph neural network. Brief. Bioinform. 25, Issue 1, bbad481. (2024).

Yu, X. et al. iDNA-OpenPrompt: OpenPrompt learning model for identifying DNA methylation. Front. Genet. 15, 1377285. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2024.1377285 (2024).

Bilal, A. & Sun, G. Neuro-optimized numerical solution of non-linear problem based on Flierl–petviashivili equation. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 1166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-2963-1 (2020).

Bilal, A., Liu, X., Long, H., Shafiq, M. & Waqar, M. Increasing crop quality and yield with a machine learning-based crop monitoring system. Computers Mater. Continua. 76 (2), 2401–2426. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2023.037857 (2023).

Bilal, A. et al. BC-QNet: a quantum-infused ELM model for breast cancer diagnosis. Comput. Biol. Med. 175, 108483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.108483 (2024).

Bilal, A. et al. Breast cancer diagnosis using support vector machine optimized by improved quantum inspired grey wolf optimization. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 10714. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-61322-w (2024).

Naeem, A. et al. SNC_Net: skin Cancer detection by integrating handcrafted and deep learning-based features using Dermoscopy images. Mathematics. 12 (7), 1030 (2024).

Naeem, A. & Anees, T. DVFNet: a deep feature fusion-based model for the multiclassification of skin cancer utilizing dermoscopy images. Plos ONE, 19 (3), e0297667. (2024).

Riaz, S., Naeem, A., Malik, H., Naqvi, R. A. & Loh, W. K. Federated and transfer learning methods for the classification of Melanoma and Nonmelanoma skin cancers: a prospective study. Sensors. 23 (20), 8457 (2023).

Naeem, A., Anees, T., Fiza, M., Naqvi, R. A. & Lee, S. W. SCDNet: a deep learning-based framework for the multiclassification of skin cancer using dermoscopy images. Sensors. 22 (15), 5652 (2022).

Naeem, A. & Anees, T. A Multiclassification Framework for skin Cancer detection by the concatenation of Xception and ResNet101. J. Comput. Biomedical Inf. 6 (02), 205–227 (2024).

Naeem, A., Khan, A. H., u din Ayubi, S. & Malik, H. Predicting the Metastasis ability of prostate Cancer using machine learning classifiers. J. Comput. Biomedical Inf. 4 (02), 1–7 (2023).

Ayesha, H., Naeem, A., Khan, A. H., Abid, K. & Aslam, N. Multi-classification of skin Cancer using Multi-model Fusion technique. J. Comput. Biomedical Inf. 5 (02), 195–219 (2023).

Solanki, S., Singh, U. P., Chouhan, S. S. & Jain, S. Brain tumor detection and classification using intelligence techniques: an overview. IEEE Access. 11, 12870–12886 (2023).

Solanki, S., Singh, U. P., Chouhan, S. S. & Jain, S. A systematic analysis of magnetic resonance images and deep learning methods used for diagnosis of brain tumor. Multimedia Tools Appl. 83 (8), 23929–23966 (2024).

Patel, R. K. & Kashyap, M. Automated screening of glaucoma stages from retinal fundus images using BPS and LBP-based GLCM features. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 33 (1), 246–261 (2023).

Patel, R. K. & Kashyap, M. The study of various registration methods based on maximal stable extremal region and machine learning. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng.: Imaging Vis. 6, 1–8 (2023).

Yu, Z., Kaizhi, S., Jianwen, H., Guanyu, Y. & Yonggang, W. A. A deep learning-based approach toward differentiating scalp psoriasis and seborrheic dermatitis from dermoscopic images. Front. Med. 9, 965423. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.965423 (2022).

AlDera, S. A. & Othman, M. T. B. A Model for Classification and Diagnosis of Skin Disease using Machine Learning and Image Processing Techniques. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. (IJACSA). 13 (5), 2022. https://doi.org/10.14569/IJACSA.2022.0130531 (2022).

Aijaz, S. F., Khan, S. J., Azim, F., Shakeel, C. S. & Hassan, U. Deep Learning Application for Effective Classification of Different Types of Psoriasis. J. Healthcare Eng. 2022, 7541583. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/7541583 (2022).

Li, F-L. et al. Deep learning in skin Disease Image Recognition: a review in IEEE Access. 8, 208264–208280. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3037258 (2020).

Yu, K., Syed, M. N., Bernardis, E. & Gelfand, J. M. Machine learning applications in the evaluation and management of Psoriasis: a systematic review. J. Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 5 (4), 147–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/2475530320950267 (2020).

Peng, L., Na, Y., Changsong, D., Sheng, L. & Hui, M. Research on classification diagnosis model of psoriasis based on deep residual network. Digit. Chin. Med. 4 (2), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcmed.2021.06.003 (2021).

Rashid, M. S. et al. Automated detection and classification of psoriasis types using deep neural networks from dermatology images. SIViP. 18, 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11760-023-02722- (2024).

Yang, S., Zhou, D., Cao, J. & Guo, Y. LightingNet: An Integrated Learning Method for Low-Light Image Enhancement, in IEEE Transactions on Computational Imaging. 9, 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCI.2023.3240087 (2023).

Litjens, G., Kooi, T., Bejnordi, B. E., Setio, A. A., Ciompi, F., Ghafoorian, M., Van der Laak, J. A., van Ginneken B. & Sánchez, CI. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Medical Image Analysis. 42, 60–88 (2017).

Wu, H. et al. A deep learning, image based approach for automated diagnosis for inflammatory skin diseases. Annals Translational Med. 8 (9), 581. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2020.04.39 (2020).

Yang, Y. et al. A convolutional neural network trained with dermoscopic images of psoriasis performed on par with 230 dermatologists. Comput. Biol. Med. 139, 104924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104924 (2021).

Nieniewski, M., Chmielewski, L. J., Patrzyk, S. & Wozniacka, A. Studies in differentiating psoriasis from other dermatoses using small data set and transfer learning. J. Image Video Proc. 2023 (7). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13640-023-00607-y (2023).

Zhao, S. et al. Smart identification of psoriasis by images using convolutional neural networks: a case study in China. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol.: JEADV. 34 (3), 518–524. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.15965 (2020).

Fink, C. et al. Intra- and interobserver variability of image-based PASI assessments in 120 patients suffering from plaque-type psoriasis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatology Venereology: JEADV. 32 (8), 1314–1319. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.14960 (2018).

Raj, R., Londhe, N. D. & Sonawane, R. Automated psoriasis lesion segmentation from unconstrained environment using residual U-Net with transfer learning. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 206, 106123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2021.106123 (2021).

Hsieh, K. Y. et al. A mask R-CNN based automatic assessment system for nail psoriasis severity. Comput. Biol. Med. 143, 105300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105300 (2022).

Shrivastava, V. K., Londhe, N. D., Sonawane, R. S. & Suri, J. S. Computer-aided diagnosis of psoriasis skin images with HOS, texture and color features: a first comparative study of its kind. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 126, 98–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2015.11.013 (2016).

Shtanko, A. & Kulik, S. Preliminary expriments on psoriasis classification in images. Proc. Comput. Sci. 213, 250–254,2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2022.11.063 (2022).

Yaseliani, M. et al. Diagnostic clinical decision support based on deep learning and knowledge-based systems for Psoriasis: from diagnosis to Treatment options. Comput. Ind. Eng. 109754 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2023.109754 (2023).

Okamoto, T., Kawai, M., Ogawa, Y., Shimada, S. & Kawamura, T. Artificial intelligence for the automated single-shot assessment of psoriasis severity. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatology Venereology: JEADV. 36 (12), 2512–2515. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18354 (2022).

Schaap, M. J. et al. Image-based automated Psoriasis Area Severity Index scoring by Convolutional Neural Networks. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatology Venereology: JEADV. 36 (1), 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.17711 (2022).

Lin, Y. L., Huang, A., Yang, C. Y. & Chang, W. Y. Measurement of Body Surface Area for Psoriasis Using U-net Models. Comput Math Methods Med. 2022, 7960151. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/7960151 (2022).

George, Y., Aldeen, M. & Garnavi, R. Automatic Scale Severity Assessment Method in Psoriasis skin images using local descriptors. IEEE J. Biomedical Health Inf. 24 (2), 577–585. https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2019.2910883 (2020).

George, Y., Aldeen, M. & Garnavi, R. Psoriasis image representation using patch-based dictionary learning for erythema severity scoring. Comput. Med. Imaging Graphics: Official J. Comput. Med. Imaging Soc. 66, 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compmedimag.2018.02.004 (2018).

Dash, M., Londhe, N. D., Ghosh, S., Raj, R. & Sonawane, R. S. A cascaded deep convolution neural network based CADx system for psoriasis lesion segmentation and severity assessment. Appl. Soft Comput.91 (106240). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2020.106240 (2020).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., Sun, J. & Recognition, P. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition, (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2016, pp. 770–778. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.90 (2016).

Pratt, H., Coenen, F., Broadbent, D. M., Harding, S. P. & Zheng, Y. Convolutional neural networks for diabetic retinopathy. Procedia Comput. Sci. 90, 200–205 (2016).

Acknowledgements

CC and RM created the concept of the study and devised the algorithms. SN and UA analyzed the data and implemented the methodology. SN wrote the manuscript. RM and CC supervised it. AA validated the results. All the authors read and approved the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CC and RM conceptualized the study and designed the problem framework. CC devised the algorithms. SN and UA analyzed the data and implemented the methodology. SN and RM wrote the manuscript. RM and CC supervised it. AA validated the results. All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work Mr. Sumit had used Grammarly (free software version) in order to check the grammar used in the sentences and change them with their proper format in context to the raw draft of the author. After using this tool, Mr. Sumit reviews and edited the content of the publication as needed and takes(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chakraborty, C., Achar, U., Nayek, S. et al. CAD-PsorNet: deep transfer learning for computer-assisted diagnosis of skin psoriasis. Sci Rep 14, 26557 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76852-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76852-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Machine learning and deep learning based psoriasis recognition system: evaluation, management, prognosis—where we are and the way to the future

Artificial Intelligence Review (2025)

-

AI in psoriatic disease (“PsAI”): Current insights and future directions

Clinical Rheumatology (2025)