Abstract

Despite recommendations to reduce sweet-tasting foods and beverage consumption, there is limited understanding of our ability to adapt to a less sweet diet and the optimal method for doing so. Thus, we conducted two parallel, double-blind, randomized controlled trials in the USA and Mexico to investigate whether different methods of reducing sweetness could change sweetness preferences. Over 6 months, habitual consumers of full-sugar sweetened (FSS-CSD) or low-calorie sweetened carbonated soft drinks (LCS-CSD) consumed a full sweetness CSD (Control), CSD with gradually decreasing sweetness levels (StepR), and a reduced sweetness test CSD (DirR). The StepR and DirR methods were similarly effective in helping the USA FSS-CSD cohort maintain their preference for reduced-sweetness CSD, without affecting sweetness intensity perception. However, neither method significantly impacted the sweetness intensity perception or preference of the USA LCS-CSD cohort, and the FSS-CSD and LCS-CSD cohorts in Mexico. Nevertheless, participants from both sweetness reduction groups in all cohorts were more willing to purchase reduced sweetness CSD compared to Control, underscoring the potential for consumer acceptance of less sweet beverages regardless of adaptation strategies.

This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as NCT04609657 and NCT05010408.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) currently recommends that the intake of free sugars (defined as monosaccharides and disaccharides added to foods, plus sugars that are naturally present in honey, syrups, and fruit juices) be reduced to less than 10% of total energy intake1. This recommendation is based on findings from several observational studies linking sugar consumption to increased risk of dental caries and weight gain, especially from sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB)1,2. To reduce sugar intake, various authoritative bodies suggest reducing the consumption of sweet-tasting foods and beverages, regardless of the source of sweetness (i.e., caloric and low/no calorie sweeteners), due to the presumed link between attraction to sweetness and developing unhealthy eating patterns1,3.

The recommendation to limit the sweetness of the overall diet is based on a hypothesis that increased exposure to sweet-tasting foods and beverages could train our palates to crave sweetness, leading to a preference for sweet taste and ultimately resulting in obesity. Conversely, it is believed that if lower sweetness options are available, consumers could adapt and reduce their intake of energy and sugar, promoting weight management4. However, the scientific evidence supporting these hypotheses is lacking, as they overlook the various factors that influence sweetness preference and the complex nature of obesity5,6. Additional research is required to test these hypotheses and establish if there is a link between sweet taste and health.

The liking for sweetness is both innate and universal, hypothesized as an evolutionary advantage to more accurately identify energy-rich foods7. However, despite the universal trait of liking sweetness, there are large inter-individual differences regarding which specific tastes and sweetness levels are liked the most. Some candidate determinants of sweetness preference are difficult, if not impossible, to change such as age, ethnicity, and genetics6. However, there is limited scientific evidence to suggest whether repeated exposure to sweet taste alters the degree of sweetness liking or not. Multiple studies in both children and adults reveal no clear, consistent support for a relationship between sweet taste exposures and subsequent preferences or subsequent sweet food intake8. Interventions lasting less than a month have generally reported that increased exposure to sweetened stimuli results in decreased preferences for sweetness. However, the findings from cohort studies and interventions of longer duration are limited and largely inconclusive. This is due to a variety of factors, including inconsistencies in assessment, insufficient control of the frequency and quantity of sweet taste exposure, inadequate consideration of overall diet, inadequate sample sizes, and insufficient trial duration to reflect habitual behavior8.

A related research question is whether the consumer’s palate can adapt to increased or decreased levels of sweetness. Several clinical trials suggest the possibility of adaptation and acceptance of less sweet products. One study showed that researchers were able to decrease the sucrose concentration of test drinks by 50% before the participants expressed dissatisfaction with the new taste. The stepwise reduction protocol was effective in reducing an individual’s sweet preference in a reasonably short time frame, with an average of 10 days to reach the lowest satisfactory sugar concentration9. Another study found that the direct reduction (sudden reduction in sweetness level) group enjoyed a 15.7% reduced-sugar biscuit, while the stepwise reduction (gradual reduction in sweetness level) group showed no change in liking for any variation of biscuits after a 4-week intervention10. In a 3-month study, direct reduction in sugar intake led to an increase in perceived sweetness intensity but no change in sweet pleasantness, and participants reverted to their original sugar consumption and perceived sweetness intensity when allowed11. Finally, a 12-month study revealed that substituting SSB with unsweetened beverages significantly reduced sweet taste preference and favorite sweetness concentration (evaluated using samples of solutions ranging in sucrose concentration from 0 to 18%) but replacement of SSB with artificially sweetened beverages only reduced favorite sweetness concentration12. Unfortunately, the current evidence base is very limited and inadequate to derive concrete conclusions on the ability to adapt to a less sweet diet and the best approach to achieve this.

Thus, the present studies aimed to fill existing knowledge gaps by conducting two, 6-month randomized, controlled trials in consumers who habitually consumed sweetened carbonated beverages to examine whether exposure to different strategies to reduce sweetness could change sweetness preference and perceived sweetness intensity. The two trials were conducted in the United States of America (USA) and Mexico (MX), thus providing the opportunity to investigate the potential influence of regional and cultural differences on sweetness adaptation and acceptance of products with reduced sweetness.

Methods

Study design

This manuscript reports results for two clinical trials on sweetness adaptation to sweetened carbonated beverages over time. These were randomized, double-blind, controlled, parallel clinical trials conducted in the USA (Study 1) and Mexico (Study 2). These two locations were chosen due to differences in background diet (e.g., SSB consumption tends to be higher in Mexico compared to the USA) and consumer familiarity (orange-flavored carbonated soft drink (CSD) is widely consumed in Mexico but not in the USA). Both studies were conducted in healthy adults who were habitual full-sugar sweetened (FSS) CSD consumers (FSS-CSD cohort) or habitual low-calorie sweetened (LCS) CSD consumers (LCS-CSD cohort). Participants from both the FSS-CSD and LCS-CSD cohorts were randomized to one of three interventions over 6 months: (1) control (C) whereby participants consumed full sweetness test CSD daily; (2) stepwise reduction (StepR) whereby participants gradually decreased the sweetness level of their daily test CSD; and (3) direct reduction (DirR) whereby participants immediately consumed a reduced sweetness test CSD daily (Fig. 1). Before starting their intervention (Baseline, Month 0) and monthly thereafter, participants rated their liking of the different CSDs of varied sweetness levels as well as the sweetness intensity of different sucrose-water solutions with varied sucrose content (i.e., 3, 6, 9, and 12% sucrose).

An institutional review board (IntegReview, LLC, Austin, TX; 15/10/2020, BIO-2003) approved all study-related material including the protocol and informed consent documents before initiation of the study in the USA. Before study commencement and participant recruitment in Mexico, the study protocol along with all accompanying documents was submitted to Cofepris (Comisión Federal para la Protección contra Riesgos Sanitarios). Signed informed consent and authorization for the use of protected health information were provided by the participants before implementing any protocol-specific procedures. The USA and Mexico studies were registered in the clinicaltrials.gov database (NCT04609657 on 30/10/2020 and NCT05010408 on 18/8/2021, respectively) before enrollment and were conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice Guidelines, the Declaration of Helsinki13, and the United States Code of Federal Regulation Title 21. The USA study took place at Biofortis Research (Addison, IL) between November 2020 and May 2021 and the Mexico study took place at Mérieux NutriSciences (MXNS: Naucalpan de Juárez, México) between August 2021 and February 2022.

Participants

Participants were self-reported healthy men and women aged 25–55 years, who reported: (1) habitually consuming 1–2 cans of CSDs daily (sugar-sweetened for FSS-CSD cohort and LCS-sweetened for LCS-CSD cohort); (2) agreed to consume at least one can of orange-flavored CSD daily for the entire duration of the study; (3) had internet access via computer, phone or other device; and (4) were able to maintain internet access throughout the trial to complete daily online questionnaires. Exclusion criteria included regular smokers (> 1 cigarette/week), history or presence of type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus, non-average dietary habits (e.g., vegetarian diets, intermittent fasting), alcohol or substance abuse, phenylketonuria, or pregnancy. All participants provided informed consent before the start of any study procedures. At the screening visit, participants completed a brief medical history questionnaire in addition to the assessment of height, weight, body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), vital signs, and review of inclusion/exclusion criteria to determine eligibility. Participants from each cohort were then randomized (1:1:1) to one of the study interventions based on a statistician-generated allocation sequence using a permuted blocks algorithm in SAS PROC PLAN. The sequence was uploaded onto the electronic case report form platform (Medrio, Inc., San Francisco, CA). Once a participant qualified for the study, the randomization module was used to assign the study product which kept all personnel involved with the data collection, analysis, and interpretation blinded to the groups assigned to participants.

Intervention

Study products were orange-flavored CSD (PepsiCo, Purchase, NY) that were customized to specific sweetness levels using sugar (i.e., sugar-sweetened CSD) for the FSS-CSD cohort or a blend of LCS (i.e., LCS-sweetened CSD) for the LCS-CSD cohort. The C group of the FSS-CSD cohort consumed the full sweetness sugar-sweetened test CSD i.e., 13 g sugar/100 mL (or 13°Brix). For sweetness, the FSS-CSD contained added sugars (high fructose corn syrup and/or sugar depending on country and product), while the LCS-CSD replaced these added sugars with a low-calorie sweetener blend consisting of aspartame, acesulfame potassium, and sucralose. Brix equivalents were determined by multiplying each sweetener amount by the standard literature amounts of aspartame (200 times sweeter than sucrose), acesulfame K (200 times sweeter than sucrose), and sucralose (600 times sweeter than sucrose). Thus, lower sweetness levels were created by appropriate percent reductions of HFCS and/or sugar or the LCS mixture (at the same ratio). All other aspects of beverage formulation were representative of commercially available products. Internal researchers tasted formulations to ensure comparability prior to production.

Participants randomized to the StepR group of the FSS-CSD cohort consumed the sugar-sweetened 13°Brix test CSD during Month 1, 11°Brix test CSD during Month 2, 9°Brix test CSD during Month 3, and 7°Brix test CSD during Months 4, 5, and 6. Participants randomized to the DirR group of the FSS-CSD cohort consumed the most reduced sweetness beverage which consisted of a 7°Brix test CSD. Similarly, the C group of the LCS-CSD cohort consumed the full sweetness LCS-sweetened test CSD i.e., 13 g sugar equivalents (eq.)/100 mL (or 13°Brix eq.). Participants randomized to the StepR group of the LCS-CSD cohort consumed the LCS-sweetened 13°Brix eq. test CSD during Month 1, 11°Brix eq. test CSD during Month 2, 9°Brix eq. test CSD during Month 3, and 7°Brix eq. test CSD during Months 4, 5, and 6. Participants randomized to the DirR group of the LCS-CSD cohort consumed the most reduced sweetness beverage which was the 7°Brix eq. test CSD.

Participants were instructed to consume one to two 330 mL cans of the test CSD daily for the 6 months of the intervention period. Beverages were provided as single-serving cans, labeled with the coded group allocation. Participants were also asked to abstain from beverages pre-sweetened with caloric or low-calorie sweeteners (LCS), except the test CSD, as well as limit the addition of caloric or LCS into beverages (e.g., sugar in coffee). Otherwise, participants were instructed to maintain habitual exercise, meal/diet, and medication/supplementation use during the study. Participants were instructed to complete an electronic daily study beverage diary which was used to determine compliance.

Sweetness liking

At baseline and monthly visits during the intervention period, participants were instructed to taste a test CSD at four sweetness levels (i.e., 7, 9, 11, and 13°Brix or °Brix eq. whereby one of these was the test CSD that participants were currently consuming based on their randomized group. For example, those randomized to the C group would have been consuming the 13°Brix or °Brix eq. test CSD at the time. Participants in the FSS-CSD cohort tasted the sugar-sweetened test CSDs while those in the LCS-CSD tasted the LCS-sweetened test CSDs. Chilled refrigerated samples were provided in 3 oz (89 mL) portions in a randomized order. Participants were instructed to drink at least half of the sample by taking a few mouthfuls (at least 3), and swallowing each sip. Each sample testing was separated by 2 min during which participants were asked to rinse their mouth with water. Sweetness liking was rated using a 9-point Likert scale ranging (from 1 = “dislike extremely” to 9 = “like extremely”).

Sweetness intensity perception

In addition to sweetness liking, participants were required to rate the sweetness intensity of sucrose solutions. At baseline and monthly visits during the intervention period, participants from both the FSS-CSD and LCS-CSD cohorts were instructed to taste four different sucrose-water solutions at varying sweetness levels (i.e., 3, 6, 9, and 12% sucrose) in a randomized order. Room temperature samples were provided in 10 mL (0.3 oz) portions. Participants were instructed to take the entire sample in their mouths, swish the sample around and then swallow. Each sample testing was separated by 1 min during which participants were asked to rinse their mouth with water. The sweetness intensity of these solutions was rated by participants by marking 117-mm printed general labeled magnitude scales. The scales included the following descriptors: “barely detectable” (1.7 mm), “weak” (7.9 mm), “moderate” (21.6 mm), “strong” (41.9 mm), “very strong” (62.2 mm), and “strongest imaginable sensation of any kind” (117 mm).

Purchase intent

At the end of the 6-month intervention period, participants were asked to rate the likelihood of purchasing the different sweetness level test CSDs. Purchase intent was rated as Definitely would not buy, Probably would not buy, Might or might not buy, Probably would buy, and Definitely would buy.

Dietary analysis

Participants were instructed to record their diet on three non-consecutive days including one weekend day using 3-d diet records collected before the start of the intervention and monthly during the 6-month intervention period. The daily energy and selected nutrient intakes for each participant were calculated using a combination of nutrition facts of packaged foods and Food Processor SQL Nutrition Analysis and Fitness Software (version 10.4.0, ESHA Research, Salem, OR).

Body weight

Body weight was assessed at baseline and during the final visit at the end of the 6-month intervention. Participants were asked to empty their bladder/bowels, change into a gown, and remove their shoes before their weight was obtained using digital and non-digital scales (US: Health-O-Meter Professional 349KLX, Sunbeam Products, Boca Raton, FL, USA; Mexico: Nuevo Leon Clinic 160, Monterrey, MX and Conair Weight Watchers WW800ES, East Windsor, NJ, USA). Weight was recorded to the nearest 0.1 lb (0.045 kg).

Aftertaste

Participants were asked if they detected an aftertaste after consuming each test CSD. If a participant indicated the presence of an aftertaste, he/she was asked to select one or more attributes that best described the aftertaste from a list of pre-identified attributes: sweet, juicy, refreshing, tart/sour, natural, licorice, artificial, tastes like a diet beverage, metallic/chemical, soapy, or bitter.

Statistical analysis

The study was designed to have 80% power at a two-sided 0.05 significance level to detect a mean liking response (scale range 1–9) difference of 1.0 between any two intervention groups. Assuming a standard deviation of 1.08, an evaluable sample size of 24/arm (total of 72 per cohort) was targeted and 84 participants per cohort (total of 168 participants) were randomized to account for an estimated 15% attrition.

The co-primary outcome measures were (1) change in sweetness liking of the test CSD (7, 9, 11, and 13°Brix or °Brix eq.) and (2) sweetness intensity perception of the sucrose solutions (3, 6, 9, 12%) over the 6-month intervention period between the DirR and StepR groups compared to the C. The impact of the intervention group (i.e., C, StepR, or DirR) on sweetness intensity perception and sweetness liking over time was evaluated with a repeated measures mixed model. Fixed effects contained terms for the main effects (month, group, sucrose solution/ test CSD), two-way interactions (month*group, group*sucrose solution/ test CSD, month*sucrose solution/ test CSD), and 3-way interaction (month*group*sucrose solution/ test CSD). Month was treated as a continuous variable and was assumed to be linear over time. Additionally, a random intercept was included. The correlation between measurements of a participant within a given month was modeled with the compound symmetry structure. A significant 3-way interaction indicates that at least one of the 2-way interactions changes across the third variable. If the 3-way interaction was significant at the 0.10 level, then the joint test of each two-way interaction was conducted using a contrast statement. If the joint test was significant at the 0.05 level, then the comparisons were further decomposed. For the sweetness intensity perception measure, the log(x + 1) transformation was applied to stabilize the variance, and back-transformed estimates were provided. Briefly, the 3-way interaction significance level of 0.10 was pre-specified in the statistical analysis plan to prevent overfitting. While the sample size calculation was sufficiently powered for pairwise comparisons to the control at a single time and single level within the third factor, the study design and research question were more complex and thus, a 3-way interaction was explored. The P-value from the 3-way interaction term was then used as a decision tool for when to decompose it to the respective 2-way interactions of interest. This stepwise procedure was implemented to control the number of tests performed. Because the study was not powered for a 3-way interaction, and the initial P-values were used for decision making steps, a marginally significant P-value of 0.10 was selected. In other words, this error level was selected to state whether or not further decomposition of the 3-way interaction was warranted to avoid overtesting.

Purchase intent was dichotomized to probably/definitely would buy compared to indifferent or probably/definitely would not buy. For each beverage, the proportion that would probably/definitely would buy was compared by randomized groups with the Fisher’s exact test. The Fisher’s exact test was used due to low cell counts (< 5) for the per-protocol (PP) population and some of the beverages.

A repeated measures model was used to evaluate the impact of intervention on each dietary intake measure (total calories, % of total calories from protein, fat, total sugar, and carbohydrates, as well daily intakes of dietary total sugar [g], servings of LCS, as well as the dietary sweetness [with and without calorie adjustments]). Dietary sweetness reflects the sum of dietary sugars (g) and sugar equivalents for dietary LCS (g). Sugar equivalents for dietary LCS were obtained by matching each LCS-containing item to a sugar-sweetened counterpart (e.g., diet cola-regular cola or sucralose-sugar)14. The amount of sugar of the sugar-sweetened counterparts was used as the sugar equivalent of the LCS-containing items. The model included terms for group, month (continuous), and group*month interaction, and a quadratic month term. Model-derived means, along with the respective 95% confidence interval, were estimated at each month and plotted.

The aftertaste of the different test CSDs was described with counts and percentages by the respective intervention groups at the respective time points (Months 0 through 6). Because specific aftertaste attributes were only selected if an aftertaste was detected by participants, the aftertaste attributes were analyzed in the subgroup indicating an aftertaste at each time point. Finally, the within-group change in body weight was analyzed using Wilcoxon signed-rank test and between-group differences were analyzed using the Kruskall-Wallis test.

All analyses were performed for the intent-to-treat (ITT) population consisting of all randomized participants and the PP population which excluded participants who early terminated or deviated from the protocol (e.g., missed visits). Significant P-values (defined a priori) were considered at α = 0.05, two-sided unless otherwise specified. All analyses were conducted using SAS for Windows (version 9.4, Cary, NC) and/or R (version 3.6.0, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Only results for the ITT analysis are presented herein and any differences between the ITT and PP populations are stated.

Results

Study 1 (USA)

Participants and compliance

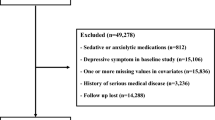

A summary of the participant disposition is provided in Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2. A total of 169 participants (85 for USA FSS-CSD cohort and 84 for USA LCS-CSD cohort) were screened for participation and 168 participants were randomized (84 for each cohort). All 84 randomized participants were included in the ITT analysis for both cohorts. For the PP analysis, 65 and 66 participants were included in the USA FSS-CSD and USA LCS-CSD cohorts, respectively. Baseline characteristics were similar between the USA FSS-CSD and USA LCS-CSD cohorts (Table 1). For the USA FSS-CSD cohort, compliance was 86.3 ± 24.6% (mean ± standard deviation) and 96.3 ± 5.4% for the ITT and PP, respectively. For the USA LCS-CSD cohort, compliance was 90.4 ± 20.8% and 97.7 ± 3.2% for the ITT and PP, respectively.

Sweetness liking

USA FSS-CSD. The 3-way interaction for Month*Group*Test CSD was significant (P < 0.1) for the ITT population (P = 0.082), but was not maintained for the PP population (P = 0.117), and thus, possible changes in 2-way interactions were explored. The Month*Group interaction was not significant (P > 0.05) for the 11°Brix and 13°Brix test CSDs, suggesting these two sweetest CSDs were equally liked by all intervention groups over time. However, the Month*Group interaction was significant for the 7°Brix (P = 0.006) and 9°Brix (P = 0.018) sugar-sweetened test CSDs. As shown in Fig. 2A, the sweetness liking ratings for the C group for the 7°Brix test CSD appear to be decreasing with time while those for the StepR and DirR groups appear to be unchanged or slightly increasing over time. Similarly, for the 9°Brix test CSD, the sweetness liking ratings for the C group appear to be decreasing with time while the sweetness liking ratings for the DirR group appear to be unchanged or slightly increased over time.

Month*Group interaction by test carbonated soft drink (CSD) sweetness level (7, 9, 11, and 13 °Brix or °Brix eq.) for sweetness liking for the USA full-sugar sweetened CSD (FSS-CSD) cohort (A) and USA low-calorie sweetened CSD (LCS-CSD) cohort (B). The impact of intervention group (i.e., Control, Stepwise Reduction, or Direct Reduction) on sweetness liking over time was evaluated with a repeated measures mixed model followed by the joint test of Month*Group interaction conducted using a contrast statement. Data are presented as model-derived means (95% confidence interval). The Month*Group interaction was significant for the 7°Brix (P = 0.006) and 9°Brix (P = 0.018) sugar-sweetened CSD for the USA FSS-CSD cohort. No other significant effects were observed. CI confidence interval, LS-Mean least square mean.

USA LCS-CSD. The 3-way interaction for Month*Group*Test CSD was not significant (P > 0.1) for the ITT population and the PP population (Fig. 2B) suggesting a lack of evidence of an interaction between intervention groups (i.e., C, DirR, and StepR) over time and across the different LCS-sweetened test CSDs; thus, no further analysis was performed.

Sweetness intensity perception

USA FSS-CSD. The 3-way interaction for Month*Group*Sucrose Solution was not significant (P > 0.1; Fig. 3A), suggesting a lack of evidence of an interaction between intervention groups (i.e., C, DirR, and StepR) over time and across the different sucrose solutions; thus, no further analysis was performed.

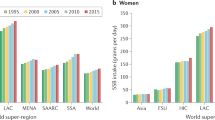

Month*Group interaction by sucrose solution level (3, 6, 9, 12% sucrose) for sweetness intensity for the USA full-sugar sweetened carbonated soft drink (FSS-CSD) cohort (A) and USA low-calorie sweetened carbonated soft drink (LCS-CSD) cohort (B). The impact of intervention group (i.e., Control, Stepwise Reduction, or Direct Reduction) on sweetness intensity perception over time was evaluated with a repeated measures mixed model followed by the joint test of Month*Group interaction conducted using a contrast statement. The log(x + 1) transformation was applied to stabilize the variance for sweetness intensity and data are presented as back-transformed model-derived means (95% confidence interval). The slopes over time for the Stepwise Reduction group for the 9% and 12% sucrose solutions were significantly different compared to that for the Direct Reduction group (P = 0.008 and 0.010, respectively) for the USA LCS-CSD cohort. No other significant effects were observed. CI confidence interval, LS-Mean least square mean.

USA LCS-CSD. In contrast, for the USA LCS-CSD cohort, the 3-way interaction for Month*Group*Sucrose Solution was significant (P < 0.1) as were the joint tests for Month*Group (P = 0.019) and Month*Sucrose Solution (P = 0.002). Specifically, the slopes over time for the StepR group for the 9% and 12% sucrose solutions were significantly (P < 0.05) different compared to that for the DirR group (P = 0.008 and 0.010, respectively). As shown in Fig. 3B, the sweetness intensity ratings for the StepR group for the 9 and 12% sucrose solutions appear to be decreasing with time while those for the DirR group appear to be slightly increasing over time.

Purchase intent

USA FSS-CSD. Across all intervention groups, the percentage of participants who would purchase the test beverages (i.e., those who selected “definitely would buy” and “probably would buy”) was highest for the 11°Brix and 13°Brix test CSDs. Compared to the C group, those in the StepR group had greater (P < 0.05) purchase intent for the least sweet (i.e., 7°Brix) sugar-sweetened test CSD and also tended (P < 0.1) to have greater purchase intent for the second lowest sweetness level (i.e., 9°Brix) sugar-sweetened test CSD (Supplementary Table 1). Additionally, the purchase intent for the 9°Brix sugar-sweetened test CSD was greater for those in the StepR group compared to the DirR group (P < 0.1) (Supplementary Table 1).

USA LCS-CSD. Similar to the USA FSS-CSD cohort, the percentage of participants who would purchase the test beverages was highest for the 11°Brix eq. and 13°Brix eq. test CSDs with no difference in purchase intent between the intervention groups. Those in the StepR and DirR groups had greater (P < 0.05) purchase intent for the least sweet (i.e., 7°Brix eq.) LCS-sweetened test CSD compared to the C (Supplementary Table 1).

Dietary analysis and body weight

There were no differences between groups for dietary intake measures analyzed including total calories, carbohydrates, fats, and protein (data not shown) as well as for dietary sugars and dietary sweetness for the USA FSS-CSD and USA LCS-CSD cohorts as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3a and b. Additionally, body weight changes from baseline to end of study were not different between intervention groups for either cohort (Supplementary Table 2). However, within-group analysis indicates a significant (P < 0.05) increase in body weight (2.1 ± 3.2 kg) from baseline at the end of the 6-month intervention period for the C group for the USA FSS-CSD cohort only. No other significant within-group differences were observed.

Aftertaste

In both cohorts, the proportion of participants reporting an aftertaste did not appear to be affected by intervention group or sweetness level (data not shown). The proportion of participants who reported “sweet” and “juicy” aftertastes appeared to increase with sweetness level for both cohorts. Interestingly, in the USA FSS-CSD cohort, those reporting “artificial” or “tastes like a diet beverage” aftertastes appeared to decrease with increasing sweetness levels while these aftertaste attributes did not appear to be affected by sweetness levels in the USA LCS-CSD cohort.

Study 2 (Mexico)

Participants and compliance

A summary of the participant disposition is provided in Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5. A total of 208 participants (103 for MX FSS-CSD cohort and 105 for MX LCS-CSD cohort) were screened for participation and 208 participants were randomized. All 208 randomized participants were included in the ITT analysis for both cohorts. For the PP analysis, 73 and 72 participants were included in the MX FSS-CSD and MX LCS-CSD cohorts, respectively. Baseline characteristics were similar between the MX FSS-CSD and MX LCS-CSD cohorts (Table 2).

For the MX FSS-CSD cohort, compliance was 79 ± 30% and 95 ± 7% for the ITT and PP, respectively. For the MX LCS-CSD cohort, compliance was 78 ± 33% and 97 ± 5% for the ITT and PP, respectively.

Sweetness liking

For both the MX FSS-CSD and MX LCS-CSD cohorts, the 3-way interaction for Month*Group*Test CSD was not significant (P > 0.1; Fig. 4), suggesting a lack of evidence of an interaction between intervention groups (i.e., C, DirR, and StepR) and the different test CSD over time in both cohorts; thus, no further analysis was performed.

Month*Group interaction by test carbonated soft drink (CSD) sweetness level (7, 9, 11, and 13°Brix sugar or °Brix eq.) for sweetness liking for the MX full-sugar sweetened CSD (FSS-CSD) cohort (A) and MX low-calorie sweetened CSD (LCS-CSD) cohort (B). The impact of intervention group (i.e., Control, Stepwise Reduction, or Direct Reduction) on sweetness liking over time was evaluated with a repeated measures mixed model followed by the joint test of Month*Group interaction conducted using a contrast statement. Data are presented as model-derived means (95% confidence interval). No significant effects were observed. CI confidence interval, LS-Mean least square mean.

Sweetness intensity perception

For both the MX FSS-CSD and MX LCS-CSD cohorts, the 3-way interaction for Month*Group*Sucrose Solution was not significant (P > 0.1; Fig. 5), suggesting a lack of evidence of an interaction between intervention groups (i.e., C, DirR, and StepR) over time and across the different sucrose solutions in both cohorts; thus, no further analysis was performed.

Month*Group interaction by sucrose solution level (3, 6, 9, 12% sucrose) for sweetness intensity for the MX full-sugar sweetened carbonated soft drink (FSS-CSD) cohort (A) and MX low-calorie sweetened carbonated soft drink (LCS-CSD) cohort (B). The impact of intervention group (i.e., Control, Stepwise Reduction, or Direct Reduction) on sweetness intensity perception over time was evaluated with a repeated measures mixed model followed by the joint test of Month*Group interaction conducted using a contrast statement. The log(x + 1) transformation was applied to stabilize the variance for sweetness intensity and data are presented as back-transformed model-derived means (95% confidence interval). No significant effects were observed. . CI confidence interval, LS-Mean least square mean.

Purchase intent

MX FSS-CSD. More than half of the participants across all intervention groups would similarly purchase the 9°Brix, 11°Brix, or 13°Brix test CSDs with no difference in purchase intent between the intervention groups (Supplementary Table 3). In contrast, the majority (> 50%) of participants were not willing to purchase the 7°Brix test CSD across all groups. Compared to C, those in the DirR group had greater (P < 0.05) purchase intent for the least sweet sugar-sweetened CSD (i.e., 7°Brix test CSD).

MX LCS-CSD. Similarly, for the MX LCS-CSD cohort, more than half of the participants across all intervention groups would purchase the 9°Brix eq., 11°Brix eq., or 13°Brix eq. test CSDs with no difference in purchase intent between the intervention groups (Supplementary Table 3). Those in the StepR and DirR groups had greater (P < 0.05) purchase intent for the least sweet (i.e., 7°Brix eq.) LCS-sweetened test CSD compared to the C group.

Dietary analysis and body weight

There were no notable differences between groups for total calorie, carbohydrate, and protein (data not shown). Descriptive statistics for dietary sugar and dietary sweetness for the MX FSS-CSD and MX LCS-CSD cohorts are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6. These were not different between groups for the MX FSS-CSD cohort. For the MX LCS-CSD cohort, there were significant month*group interaction effects for dietary sweetness, but not dietary sugar. Collectively, these measurements were lower in the DirR and StepR groups compared to C starting from Month 3 onwards.

Additionally, body weight changes from baseline to end of study werenot different between intervention groups for either cohort (Supplementary Table 4). However, the within-group analysis indicated a significant (P < 0.05) increase in body weight (1.1 ± 4.1 kg) from baseline at the end of the 6-month intervention period for the C group for the MX FSS-CSD cohort only. No other significant within-group differences were observed.

Aftertaste

In both cohorts, the proportion of participants reporting an aftertaste did not appear to be affected by intervention group or sweetness level (data not shown). The proportion of participants who reported “sweet” and “juicy” aftertastes increased with sweetness level for both cohorts (data not shown).

Discussion

Our studies aimed to determine if the preference for a reduced sweetness CSD can change over time following two different approaches to sweetness reduction: (1) a stepwise, gradual decrease in sweetness level (StepR) or (2) a direct, abrupt decrease in sweetness level (DirR) compared to C. These trials were conducted in the USA and Mexico to understand if there are regional and cultural differences in sweet taste preferences and responses. Our results suggest that both the stepwise and direct approaches to sweetness reduction are equally effective in getting habitual USA FSS-CSD consumers to maintain a degree of liking of reduced-sweetness, sugar-sweetened CSDs without affecting perceived sweetness intensity. In contrast, neither sweetness reduction approach affected sweetness liking nor sweetness intensity perception among the habitual USA LCS-CSD consumers. Similarly, neither sweetness liking nor sweetness intensity perception was affected by either approach among both habitual FSS-CSD and habitual LCS-CSD consumers in Mexico.

In general, sweetness liking ratings by the USA and MX FSS-CSD and LCS-CSD cohorts decreased with decreasing sweetness levels regardless of intervention group. Within the USA FSS-CSD cohort, sweetness liking rating for the least sweet sugar-sweetened CSD (i.e., 7°Brix) decreased over time in the C group but was similarly maintained over time in both sweetness reduction groups. It is unsurprising that the C group had the lowest liking ratings for the lower reduced sweetness CSDs as they would experience the greatest contrast effect between the lower sweetness levels (7 and 9°Brix) compared to the familiar 13°Brix sweetness level that they were consuming throughout the study. This contrast in comparison may have heightened their perception of insufficiency in the lower sweetness options, making them less appealing over time15. Additionally, repeated exposure to the lower sweetness levels may reinforce the disappointment from not meeting their expectations of the higher sweetness level, leading to amplified negative hedonic response16. In contrast, the StepR and DirR groups likely experienced a diminished contrast effect and adjusted their expectations with repeated exposure to lower sweetness levels, lessening the decrease in liking ratings observed in the C group.

In contrast to the USA FSS-CSD cohort, there were no differences in changes in sweetness liking rating over time in the USA LCS-CSD, MX FSS-CSD, and MX-LCS-CSD cohorts between either sweetness reduction groups or the C group. The observations on sweetness liking ratings could have been influenced by the aftertaste following consumption of the reduced sweetness FSS-CSD or LCS-CSD as well as regional differences. Reducing the amount of sugar in foods or beverages with a complex flavor profile affects not only sweet taste but also the overall flavor profile which may in turn impact overall product liking17. Indeed, the USA FSS-CSD cohort reported an increasing artificial and metallic aftertaste with decreasing sweetness level of the sugar-sweetened test CSD, which may have influenced how they rated their overall liking of the different sugar-sweetened test CSDs. On the other hand, there was a lack of unpleasant aftertaste (e.g., artificial or metallic) with the reduced-sweetness LCS-CSDs among the USA LCS-CSD cohort. The USA LCS-CSD cohort, comprising individuals who regularly consume low-calorie sweetened beverages, may not have been affected by the bitter, metallic, and chemical aftertastes commonly associated with LCSs18. The difference in results between the USA and Mexico cohorts is not entirely surprising. As mentioned previously, sweetness preference is multifactorial and includes determinants such as diet, ethnicity, lifestyle, and exposure/familiarity, which are expected to be different between these two countries6. While the current study provided the opportunity to investigate the potential influence of regional and cultural differences on sweetness adaptation and acceptance of products with reduced sweetness, future work should compare and identify the factors that may impact sweetness adaptation or preferences across regions.

As expected, sweetness intensity ratings were highest for the 12% sucrose solution and decreased with decreasing sucrose amounts regardless of region (USA or Mexico), cohort (FSS or LCS), or intervention group (DirR, StepR, or C). Sweetness intensity perception over time was unaffected by the sweetness reduction interventions for the FSS-CSD groups. In a previous randomized controlled trial (RCT), USA consumers of sugar- or high fructose corn syrup–sweetened soft drinks who abruptly reduced their dietary intake of simple sugars by ~ 40% (low-sugar group) for 3 months had increased perceived sweetness intensity, without any changes in sweet pleasantness/preference compared to a control group11. Another RCT also reported a reduction in sweetness intensity and preferred sweetness level following 12 months of abstinence from sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in habitual SSB consumers in the USA12. Thus, the absence of an effect on sweetness intensity perception in our study may be due to a reduction in only a single source of sweetness (i.e., sugar from CSD vs. total dietary sugar) or the shorter duration (i.e., 6 months vs. 12 months).

In contrast to the FSS-CSD groups, sweetness intensity ratings for the 9 and 12% sucrose solutions appear to be decreasing with time for the USA LCS-CSD StepR group and increasing with time for the USA LCS-CSD DirR group. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the impact of reducing the sweetness levels of habitual LCS beverages on the sweetness intensity perception of sucrose solutions. Sugar and LCS do interact differently with other taste compounds as well as taste receptors and these interactions may contribute to the difference in sweetness intensity perception over time between the LCS-CSD and FSS-CSD cohorts. The decrease in sweetness intensity ratings for the USA LCS-CSD StepR group may be due to gradual desensitization and sensory acclimatization8. Gradually reducing sweetness levels allows taste receptors to adapt slowly, leading to decreased sensitivity to sweetness. Over time, this adaptation shifts their baseline for sweetness intensity downward, making higher concentrations of sucrose feel less sweet. Additionally, the gradual changes may allow for expectation and cognitive adjustments, aligning their perception with the lower expected sweetness levels and recalibrating their internal scale for sweetness19. Conversely, the sudden sweetness reduction in the USA LCS-CSD DirR group may have heightened participants’ sensitivity to sweetness, causing higher ratings for the 9% and 12% sucrose solutions. This heightened sensitivity could persist over time, possibly due to a rebound effect or increased attention to sweetness levels after the abrupt change.

The dissociation between our sweetness liking and sweetness intensity findings is consistent with others demonstrating little to no association between sweet sensitivity and dietary intake, suggesting that testing for sweet taste threshold is not likely to be predictive of dietary intake20. This is because hedonic ratings reflects the subjective pleasure derived from an item and thus may be influenced by various factors. In the case of liking the taste of a food or beverage, associations have been observed to be influenced by body weight, habitual diet, mood, and taste sensitivity21.

Consistent with our general observations that sweetness liking ratings increased with increasing sweetness level, purchase intent was highest for the sweetest CSDs regardless of region, cohort, or intervention group. Additionally, compared to C, both sweetness reduction groups from all cohorts were more willing to purchase reduced sweetness CSDs. More than 50% of the USA FSS-CSD and USA LCS-CSD cohorts were willing to purchase the 11°Brix or 11°Brix eq. CSDs, respectively, suggesting that this level of reduced sweetness may be a viable initial marketable option for a reduced-sweetness SSB in the USA. In Mexico, most participants (> 60%) in either reduced sweetness group were willing to purchase CSDs as low as 9°Brix or 9°Brix eq., suggesting that an even lower sweetness level may be introduced to the Mexican market. Despite the promising results, our study was not designed or powered to evaluate the effect of sweetness reduction on purchase intent; thus additional studies are required to confirm our findings, to ensure consumer relevance, and to better direct product development and marketing efforts of reduced-sweetness beverages.

Overall, reducing sweetness levels of the daily test CSDs did not affect dietary intakes in the FSS-CSD and LCS-CSD cohorts in both the USA and Mexico. The measure of dietary sweetness (reflecting dietary sugar and dietary LCS) decreased regardless of region, cohort, or intervention group, suggesting adherence to instructions to limit sweetened beverages throughout the intervention period apart from the provided test CSD. Our observations are in line with those of Ebbeling et al. whereby the replacement of habitual SSB with LCS beverages or abstinence from any sweetened beverages for 12 months resulted in decreased dietary total sugar, added sugar, and total energy intake12. In another RCT, the replacement of sugar with sugar-reduced foods and beverages for 8 weeks decreased dietary total sugars and carbohydrate and increased dietary fat and protein intakes, but did not change total energy intake22. Taken together, these findings suggest that reduction in dietary sweetness did not result in dietary compensation through increased consumption of other sources of sweetness and instead contributed to decreased dietary sugar while maintaining or reducing total energy intake. However, our study was not designed or powered to evaluate the effects of sweetness reduction on dietary intake and further research is needed to examine these relationships.

We observed an increase in body weight in the C groups for both the USA and MX FSS-CSD cohorts, but not in the two sweetness reduction groups. The body weight increases in these control groups were within expected body weight fluctuations23 and thus, may not be clinically meaningful. Furthermore, there were no significant differences in body weight change between intervention groups by cohort or region and the lack of effect on body weight observed in our study is consistent with the 12-month study by Ebbeling et al.12. Body weight was a secondary outcome and this study was not designed or powered to evaluate the effects of sweetness reduction on body weight.

Strengths of this RCT include an intervention targeting a single dietary behavior (beverage consumption) as well as high retention and compliance rates across groups. In addition to assessing sweetness liking and sweetness intensity perception, we also evaluated purchase intent, thus, providing real-world applicable outcomes. One limitation of this study is that the test CSDs may not have fully replaced each participant’s regular consumption of CSDs, as they were instructed to consume 1–2 CSDs per day. Consequently, it is plausible that the participants did not consume as much CSD during the intervention as they normally would in their habitual diet. Participants were also instructed to restrict the consumption of other sweetened beverages which limited our ability to isolate the effect of the different sweetness reduction approaches on total dietary intakes. Additionally, only one flavor of CSD was used, which may have influenced ratings on liking and purchase intent. The test CSD used in the USA and Mexico studies mimics the flavor profile of an orange-flavored CSD, which is more familiar to the Mexican consumer compared to the USA consumer and may contribute to the greater acceptance within the Mexican cohorts. Thus, additional research is needed to evaluate the acceptability of other types of reduced sweetness CSDs.

In conclusion, both the stepwise and direct methods of reducing sweetness were similarly effective in helping USA consumers maintain their preference for reduced-sweetness sugar-sweetened CSDs, without altering their perception of sweetness intensity. On the other hand, gradual or sudden reduction of sweetness levels in LCS-sweetened CSDs over 6 months had little impact on the sweetness intensity perception or preference of LCS-CSD consumers in the USA. The gradual or sudden reduction of sweetness levels in daily sugar-sweetened or LCS-sweetened CSDs also had minimal effects on sweetness perception or preference among habitual FSS-CSD and LCS-CSD consumers respectively in Mexico. Nonetheless, participants from both sweetness reduction groups in all cohorts showed greater willingness to purchase reduced sweetness CSDs compared to the C group. Overall, our findings highlight the potential for both sweetness reductions methods to beneficially influence consumer behavior, though further research is needed to optimize strategies for adapting to less sweet beverages across diverse populations.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CSD:

-

Carbonated soft drink

- DirR:

-

Direct reduction

- FSS-CSD:

-

Full-sugar sweetened carbonated soft drinks

- ITT:

-

Intent-to-treat

- LCS:

-

Low-calorie sweeteners

- LCS-CSD:

-

Low-calorie sweetened carbonated soft drink

- MX:

-

Mexico

- PP:

-

Per-protocol

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- SSB:

-

Sugar-sweetened beverage

- StepR:

-

Stepwise reduction

- USA:

-

United States of America

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Policy statement and recommended actions for lowering sugar intake and reducing prevalence of type 2 diabetes and obesity in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. (2016). https://applications.emro.who.int/dsaf/EMROPUB_2016_en_18687.pdf

Malik, V. S., Pan, A., Willett, W. C. & Hu, F. B. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 98, 1084–1102. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.058362 (2013).

Pan American Health Organization. Pan American Health Organization Nutrient Profile Model. (2016). https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/18621/9789275118733_eng.pdf?sequence=9&isAllowed=y

Trumbo, P. R. et al. Perspective: measuring sweetness in foods, beverages, and diets: toward understanding the role of sweetness in health. Adv. Nutr. 12, 343–354. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmaa151 (2021).

Frood, S., Johnston, L. M., Matteson, C. L., Finegood, D. T. & Obesity complexity, and the role of the Health System. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2, 320–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-013-0072-9 (2013).

Venditti, C. et al. Determinants of sweetness preference: a scoping review of human studies. Nutrients 12 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030718

Beauchamp, G. K. Why do we like sweet taste: a bitter tale? Physiol. Behav. 164, 432–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.05.007 (2016).

Appleton, K. M., Tuorila, H., Bertenshaw, E. J., de Graaf, C. & Mela, D. J. Sweet taste exposure and the subsequent acceptance and preference for sweet taste in the diet: systematic review of the published literature. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 107, 405–419. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqx031 (2018).

Khimsuksri, S. et al. Effect of Stepwise Sugar reduction on the satisfaction of sucrose-sweetened drink. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 103, 32–35 (2020).

Biguzzi, C., Lange, C. & Schlich, P. Effect of sensory exposure on liking for fat- or sugar-reduced biscuits. Appetite 95, 317–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.07.001 (2015).

Wise, P. M., Nattress, L., Flammer, L. J. & Beauchamp, G. K. Reduced dietary intake of simple sugars alters perceived sweet taste intensity but not perceived pleasantness. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 103, 50–60. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.112300 (2016).

Ebbeling, C. B. et al. Effects of sugar-sweetened, artificially sweetened, and unsweetened beverages on cardiometabolic risk factors, body composition, and sweet taste preference: a randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 9, e015668. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.119.015668 (2020).

Ferney-Voltaire France: World Medical Association, (2008).

Kamil, A., Wilson, A. R. & Rehm, C. D. Estimated sweetness in US Diet among children and adults declined from 2001 to 2018: a serial cross-sectional surveillance study using NHANES 2001–2018. Front. Nutr. 8, 777857 (2021).

Lawless, H. T., Horne, J. & Spiers, W. Contrast and range effects for category, magnitude and labeled magnitude scales in judgements of sweetness intensity. Chem. Senses 25, 85–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/25.1.85 (2000).

Cardello, A. V. & Sawyer, F. M. Effects of disconfirmed consumer expectations on food acceptability. J. Sens. Stud. 7, 253–277 (1992).

Hutchings, S. C., Low, J. Y. Q. & Keast, R. S. J. Sugar reduction without compromising sensory perception. an impossible dream? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 59, 2287–2307. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2018.1450214 (2019).

Tan, V. W. K., Wee, M. S. M., Tomic, O. & Forde, C. G. Temporal sweetness and side tastes profiles of 16 sweeteners using temporal check-all-that-apply (TCATA). Food Res. Int. 121, 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2019.03.019 (2019).

Rolls, E. T. Taste, olfactory, and food texture processing in the brain, and the control of food intake. Physiol. Behav. 85, 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.04.012 (2005).

Tan, S. Y. & Tucker, R. M. Sweet taste as a predictor of Dietary Intake: a systematic review. Nutrients 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11010094 (2019).

Drewnowski, A., Mennella, J. A., Johnson, S. L. & Bellisle, F. Sweetness and food preference. J. Nutr. 142, 1142S–1148S. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.111.149575 (2012).

Markey, O., Le Jeune, J. & Lovegrove, J. A. Energy compensation following consumption of sugar-reduced products: a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 55, 2137–2149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-015-1028-5 (2016).

Kuzmenko, N. V., Tsyrlin, V. A., Pliss, M. G. & Galagudza, M. M. Seasonal body weight dynamics in healthy people: a meta-analysis. Hum. Physiol. 47, 676–689 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Leila Shinn for her significant contributions to manuscript revisions and Linda Derrig for her assistance with project management.

Funding

Studies were supported by PepsiCo, Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AK, CDR, SQ, PS, and ARW contributed to the design of the study. EM supervised the research. TMB, CDR, and SQ conducted the data analyses. All authors contributed to manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed and commented on subsequent drafts of the manuscript. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

AK, CDR, SQ, PS, and ARW are employees of PepsiCo, Inc. EM and TMB are employees of Biofortis Research and received funding from PepsiCo, Inc. AK, CDR, SQ, PS, ARW, EM, and TMB were involved in the design of the study, analyses, and interpretation of the data, writing of the manuscript, and decision to publish the data. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of PepsiCo, Inc.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mah, E., Kamil, A., Blonquist, T.M. et al. Change in liking following reduction in sweetness level of carbonated beverages: a randomized controlled parallel trial. Sci Rep 14, 26742 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77529-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77529-w