Abstract

Soil alkalinity and salinity are major challenges to wheat production in arid regions. Eco-friendly amendments (organic matter and bio-stimulants) offer promising solutions, but their combined effects are underexplored. This study assessed the effects of organic amendments (vermicompost, compost, and chicken manure) combined with foliar bio-stimulants (licorice root, ginger rhizome, moringa leaf extract (MLE), and potassium humate) on wheat under salt and alkalinity stress. Organic amendments combined with bio-stimulants significantly improved wheat yields by enhancing chlorophyll content, proline levels, photosynthetic pigments, water uptake, and enzyme activities. Vermicompost outperformed compost and chicken manure in improving plant physico-biochemical properties. The combination of vermicompost and MLE was most effective in increasing plant height, leaf area, and photosynthetic rate by 97, 126, and 136%, respectively, while also enhancing catalase, peroxidase, and superoxide dismutase by 65, 97, and 185%, respectively. Consequently, this resulted in 64% increase in straw yield and 27% increase in grain yield compared to controls. Additionally, nutrient uptake (N, P, and K) significantly increased, while sodium uptake decreased. Integrating vermicompost with MLE can significantly enhance wheat productivity under abiotic stress, offering a sustainable solution to improve crop resilience in arid environments. Further research is required to understand the mechanisms and optimize bio-stimulant use in agriculture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wheat (Triticum aestivumL.), a key cereal crop within the Poaceae family, plays a vital role in global food security, providing more calories and protein than any other crop. Approximately 200 million hectares are dedicated to wheat cultivation worldwide, with an average annual production of 600 million tons1. In Egypt, about 1.43 million hectares yield 9.4 million tons of wheat each year2. Given its importance, especially in regions affected by salinity stress, enhancing wheat’s tolerance to such stress is crucial3,4.

The agriculture industry sustains most of the world’s population, but soil salinity presents a significant challenge, particularly in irrigated soils. Large areas of saline soils are found in hot, dry regions, where irrigation often leads to secondary soil salinization, affecting 20% of the world’s irrigated lands5. Salinity stress, caused by high concentrations of sodium (Na) and chlorine (Cl) ions, is a major abiotic factor that limits crop production6,7,8. These ions increase osmotic pressure and cause ion-specific damage, inhibiting plant growth9. Salt stress also induces oxidative stress, generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) like hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl radicals (OH•), and superoxide radicals (O2•−), which disrupt cellular redox balance and lead to lipid peroxidation10. Salinity can further impair photosynthesis by restricting both photochemical and Calvin cycle reactions11.

To combat oxidative stress, plants possess antioxidant defense mechanisms, including enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione reductase (GSH), as well as non-enzymatic antioxidants like ascorbic acid, carotenoids, proline, tocopherols, and GSH12,13,14. However, these endogenous systems are sometimes insufficient to maintain plant health and growth. To enhance stress tolerance, plants may require exogenous support, such as plant extracts and organic amendments15,16,17.

Plant extracts provide essential nutrients, phytohormones, osmoprotectants, antioxidants, and natural growth promoters to fortify the protective antioxidant system and help plants effectively confront environmental challenges15,16,17. Extracts such as ginger (Zingiber officinale) rhizome extract (GRE), licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) root extract (LRE), and moringa (Moringa oleifera) leaf extract (MLE), have been studied for their beneficial effects on plant performance18,19. These extracts contain soluble sugars (SS), α-tocopherol, amino acids, proline, salicylic acid, ascorbic acid, specific vitamins (e.g., A, E, and B), GSH, and selenium (Se)19,20. In addition, they are rich in phytohormones like auxins, gibberellins, and zeatin-type cytokinins, along a wide range of nutrients17,21,22. As natural biostimulants, these extracts can support plant growth under various environmental stresses15,23.

Alternatively, applying vermicompost tea to the soil could be effective in mitigating certain levels of salinity. Vermicompost, a soil amendment produced through the decomposition of organic wastes and animal manure by the activity of earthworms and microorganisms, results in finely granulated soil-like particles24. Vermicompost tea, a water-based extract of solid vermicompost, contains beneficial microorganisms, soluble nutrients, and other helpful elements25. Numerous studies have demonstrated vermicompost’s positive effects on cereal plants26. For example, when applied to maize seedlings, vermicompost increased photosynthetic pigments, enabling the plants to withstand salinity stress27. Plants grown in vermicompost showed increased tolerance through stimulated enzymatic activities, enhanced protein synthesis, and improved physiological functions28. Microorganisms found in vermicompost, such as Bacillus subtilis and Azotobacter chroococcum, have been shown to enhance the growth of wheat, corn, rice, barley, and soybean, under NaCl stress conditions29. Therefore, vermicompost has the potential to enhance plant performance by alleviating the adverse effects of salinity28,29.

Organic amendments, such as manure, offer a viable alternative to chemical amendments. For instance, compost contains phytohormones like cytokinins, auxins, and gibberellic acid, which promote crop growth30,31. In sodic soils, these organic amendments increase porosity, improve soil physical properties by binding to fine soil particles into larger, water-stable aggregates32. Fertilizing with organic matter (OM) can also chemically and physically improve salt-affected soils by reducing exchangeable Na content and increasing aggregate stability33. Furthermore, organic amendments present a more sustainable and cost-effective option compared to inorganic materials for remediating saline-sodic soils34.

The combined use of gypsum and organic amendments can positively impact Na and potassium (K) concentrations, depending on the chemical composition of the amendments, particularly in calcareous saline-sodic soils35. Previous studies have affirmed the effectiveness of organic materials in managing salt-affected soils36.

As plant biostimulants, humic substances can increase nutrient availability to plants, thus enhancing growth and yield37. Root system stimulation, stress alleviation, and improved soil properties and microbial structures are all benefits of humic substances38. The enhanced permeability of the cell membrane, facilitated by humic acid, is responsible for plant growth and increased yields, facilitating the transfer of soil elements to the plant39.

Humic substances, as plant biostimulants, enhance nutrient availability, leading to improved growth and yield40. They stimulate root systems, alleviate stress, and improve soil properties and microbial structures41. Humic acid enhances cell membrane permeability, facilitating nutrient transfer and boosting plant growth under abiotic stresses41. Potassium humate (Kh), derived from humic acid, is used in soil and foliar applications to increase plant growth and production42,43. Potassium plays a key role in mitigating salinity and drought stresses, with studies showing that exogenous application of Kh improves bean growth under saline stress conditions44,45,46.

While previous studies have examined the individual effects of various compounds on wheat production under saline conditions, the combined effects of organic amendments and stimulants on wheat plants and their defense systems under saline stress remains poorly understood. To address this gap, we conducted a field study to evaluate the effectiveness of co-applying different organic amendments and stimulants in mitigating the adverse effects of soil salinity on growth, enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants, and yield. We hypothesized that combining organic amendments (e.g., vermicompost, chicken manure (CM), or compost) and stimulants (e.g., LRE, GRE, MLE, or Kh) would more effectively alleviate the negative impacts of soil salinity on wheat growth and production by enhancing both enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants.

Materials and methods

Field experiment and location

A field trial was conducted at a privately owned farm in El-Sharkia Governorate, Egypt, during the winter season of 2020/2021. The trial involved three organic amendments (2.4 tons of vermicompost ha−1, 24 tons of compost ha−1, and 24 tons of CM ha−1) and four foliar applications of stimulants (2% MLE, 2% LRE, 2% GRE, and 2.5 g Kh L−1). All stimulants were applied at a rate of 870 L ha−1. The chosen application rates were based on previous studies47,48,49,50,51,52. Each subplot measured 6.25 m2 (2.5 m × 2.5 m), and the experiment was arranged in a split-plot design with three replicates. The treatments included: (1) control (no additives); (2) MLE; (3) LRE; (4) GRE; (5) Kh; (6) vermicompost; (7) vermicompost + MLE; (8) vermicompost + LRE; (9) vermicompost + GRE; (10) vermicompost + Kh; (11) compost; (12) compost + MLE; (13) compost + LRE; (14) compost + GRE; (15) compost + Kh; (16) CM; (17) CM + MLE; (18) CM + LRE; (19) CM + GRE; and (20) CM + Kh.

The use of plants and plant parts in the current study adhered to relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

Soil sampling

Soil samples were collected at depth of 0–20 cm before applying the organic amendments and were analyzed following the method described by Sarkar and Haldar53. The soil was classified as clay, with 21.0% sand, 30.3 silt, and 48.7% clay. It had an electrical conductivity (EC) of 13.2 dS m−1, a pH of 8.13, an exchangeable Na percentage (ESP) of 15.1%, and cation exchange capacity (CEC) of 25.3 cmolc kg−1.

Preparation and addition of organic amendments

The compost, with a pH of 7.90, OM content of 39.9%, and a C/N ratio of 12.9, was prepared by combining over 50% plant residues with 50% of horse and cow excrement. This mixture was applied to the soil at 24 mg ha−1 before sowing (during soil preparation). At sowing, CM with a pH 7.8, 40.6% OM, and a C/N ratio of 8.06, was applied at a rate of 24 tons ha−1. Vermicompost, with a pH of 7.87, 40.6% OM, and C/N ratio 8.06, was applied at a rate of 2.4 tons ha−1. The compost, CM, and vermicompost were incorporated into the soil54. The properties of these organic amendments are detailed in Table S1.

Preparation and foliar applications of bio-stimulants

According to Mvumi et al55., MLE was prepared by mixing 200 g of moringa leaves with 2 L of 80% ethanol, stirring the mixture for 15 min, and subsequently filtering it. The filtrate was evaporated to remove the ethanol, and the extract was diluted to 10 L with distilled water. MLE (2.0%; 20 g leaves L−1) was applied as a foliar spray three times.

LRE was prepared as described by Ghazi48. Powdered LRE (200 g) was mixed with 10 L of water at 50°C and stirred for 24 h. The mixture was filtered, and the volume was adjusted to 10 L with distilled water. LRE (2.0%; 20 g roots L−1) was also applied as a foliar spray three times.

For GRE, ginger was washed, peeled, dried in a hot air oven at 55°C, and ground into a fine powder. The ground ginger was extracted overnight in a shaker at room temperature using 200 g in 2 L of ethanol. The ethanol was evaporated below 40°C, and the extract was filtered and diluted to 10 L with distilled water56. Ground ginger extract (2.0%; 20 g ginger L−1) was applied as a foliar spray three times.

As shown in Table S2, MLE, LRE, and GRE were chemically analyzed. In addition, Kh was obtained from Syngenta (Basel, Switzerland), with a concentration of 2.5 g L−1, as detailed in Table S3.

Cultivation of wheat, irrigation schedule and application of treatments

Healthy grains of wheat (cv. Misr 1) were sown on November 29. The Misr 1 cultivar was chosen due to its sensitivity to salt stress, a common issue in Egypt. To achieve the recommended sowing density for the study area, seeds were sown at a rate of 160 kg ha−1. Organic amendments were applied to each experimental subplot one month before sowing, followed by irrigation. The studied bio-stimulants were applied using foliar application three times: At 30, 45, and 60 days after sowing (DAS). In accordance with the Egyptian Ministry of Agriculture, traditional agricultural practices, such as conventional irrigation and mineral fertilization were used. Harvesting was completed on April 30.

Determination of wheat morphological and physiological traits

Three plants from each treatment were randomly selected at 70 days of age (booting stage) to assess their vegetative and physiological characteristics. Measurements included the size of the flag leaf blades (in cm), and the leaf blade area (in cm2) on the main stem. At harvest, samples from ten randomly selected plants were taken to estimate spike length (cm), spike weight (g), number of grain spike−1, grain yield (tons ha−1), straw yield (tons ha−1), biological yield (straw + grain; tons ha−1), and harvest index [(grain yield / biological yield) ×100).

Photosynthetic pigments and gas exchange attributes

Photosynthetic pigments were extracted from fresh leaves using pure acetone57. The extracts were filtered, and the optical density of the filtrate was measured spectrophotometrically at wavelengths of 662, 644, 440.5 nm for chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoids, respectively. Pigment concentrations (in mg g−1 fresh weight) were calculated using the following formulas:

where, E represents the optical density at the specified wavelength. Pigment concentrations were then expressed in mg g−1 fresh leaf weight.

A portable photosynthesis system LF6400XTR (LI-COR, USA) was used to measure stomatal conductance (Gs), rate of transpiration (Tr), and leaf net photosynthetic rate (Pn) between 9:00–11:00 AM.

Relative water content, membrane stability index, and proline measurements

Relative water content (RWC) was estimated using the method described by Barrs and Weatherley58. After soaking the leaves in water for three h, their fresh weight (FW) was recorded. The leaves were then weighed to determine their total weight. Following this, the samples were dried in an oven at 65°C for 24 h to obtain the dry weight (DW). RWC was calculated using the following formula:

The membrane stability index (MSI) was calculated using two sets of 200 mg fresh leaf samples, each immersed in 10 mL of double-distilled water. One set was heated at 40°C for 30 min, and the EC was measured with a conductivity bridge (C1). The second set was boiled at 100°C for 10 min and EC measurements were taken again (C2). MSI was calculated using the following formula59:

Proline levels were measured using the rapid colorimetric method described by Bates et al60. A 0.5 g fresh leaf sample was extracted in 3% (v/v) sulfosalicylic acid. After centrifuging the extract at 10,000 × g for 10 min, 2 mL of the supernatant was mixed with 2 mL of acidic ninhydrin and incubated at 90°C for 30 min. The reaction was stopped with ice, and 5 mL of toluene was added to separate the toluene fraction. After vortex mixing for 15 s, the phases were allowed to separate for 20 min at 25°C. The absorbance of the upper toluene phase was then read at 520 nm.

Determinations of mineral content

Dried powdered leaf samples (0.1 g) were digested using 2 mL of 80% perchloric acid and 10 mL of concentrated H2SO4for 12 h61. The total K and Na concentrations were measured using a flame photometer62. The total N content was determined using the micro-Kjeldahl method63. Total P was measured using the ascorbic acid method64.

Determination of antioxidant enzyme activities

Fresh leaves (0.5 g) were minced in liquid N and then stirred in 100 mM cold phosphate buffer (pH 7) for 10 min and the mixture was centrifuged at 15,000 x g for 10 min at 4°C65. The supernatants were stored at approximately 5°C for 2 h before estimating the enzymatic activities of CAT, POD, and SOD.

To assay CAT (EC1.11.1.6), 15 min of centrifugation was performed on the homogenate samples at 15,000 × g66. Hydrogen peroxide (0.1 mL, 5.9 mmol L−1) and phosphate buffer (1.9 mL, 50 mmol L−1) were added to the supernatant.

For SOD activity, methionine (5 mL), riboflavin (150 µL), and NBT (24 µL) were added to the supernatant (0.1 mL)67. To estimate POD activity (EC1.11.1.7), morpholinoethanesulphonic acid (1.3 mL), phenyl diamine (0.1 mL), and H2O2(1 mL, 30%) were added to 0.1 mL of the supernatant68,69. Absorbance readings were recorded for 3 min at 240 nm for CAT, 560 nm for SOD, and 470 nm for POD.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS software version 19.0. Significant differences among treatments were determined using Fisher’s Protected least significant difference (LSD) at p ≤ 0.05. Principal component analysis (PCA) was employed to explore the relationship among the studied variables. In the PCA ordination plot, smaller angles between arrows indicate stronger correlations between variables, while the direction of the arrows denotes positive or negative correlations. Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to examine the relationships among the study variables. PCA and regression analyses were performed with Origin Version 9 (OriginLab Corporation, USA; www.originlab.com) software.

Results

Effect of organic amendments and/or biostimulants on plant growth performance and gas exchange attributes

Compared to untreated plants, the addition of all organic amendments (vermicompost, CM, or compost) significantly improved plant height, leaf area, Pn, Tr, Gs, RWC, and MSI (Table 1). Specifically, vermicompost increased these attributes by 25.6, 55.8, 64.7, 69.9, 56.5, 30.2, and 38.4%, respectively; and CM increased them by 16.1, 30.2, 36.4, 39.6, 35.7, 21.6, and 28.7%, respectively, compared to untreated plants (Table 1).

Among the organic amendments, vermicompost was more effective than both compost and CM in enhancing plant height, leaf area, Pn, Tr, Gs, RWC, and MSI. Vermicompost significantly increased these attributes by 9.39, 24.1, 59.0, 64.4, 17.3, 9.95, and 18.8%, respectively, compared to compost, and by 8.19, 19.6, 20.8, 21.8, 15.3, 7.04, and 7.56%, respectively compared to CM. However, CM was significantly better than compost for all attributes except Gs (Table 1).

Biostimulants (MLE, LRE, GRE, and Kh) also had significant and positive effects on plant height, leaf area, Pn, Tr, Gs, RWC, and MSI compared to untreated plants (Table 1). MLE, for example, increased these attributes by 15.3, 34.1, 21.4, 25.4, 26.9, 13.9, and 16.4%, respectively; LRE increased them by 12.1, 26.5, 8.29, 9.69, 21.8, 13.3, and 13.5%, respectively; and GRE increased them by 7.11, 22.1, 5.03, 7.59, 20.3, 9.92, and 9.68%, respectively (Table 1).

The application of Kh significantly increased leaf area,Tr, Gs, RWC, and MSI by 16.7, 4.19, 10.3, 7.54, and 9.46%, respectively, relative to the control treatment (Table 1). The highest values for plant height, leaf area, Pn, Tr, Gs, RWC, and MSI were recorded with MLE application, followed by LRE, GRE, and Kh. Specifically, MLE enhanced these attributes by 2.78–28.9, 6.03-15.0, 12.1–20.4, 14.3–20.4, 4.24–15.1, 0.53–5.90, and 258 − 6.38%, respectively, compared to the other biostimulants (Table 1).

The interaction between organic amendments and biostimulants had a significant impact on the above characteristics (Table 1). The combined application of vermicompost and MLE resulted in the greatest increases in plant height, leaf area, Pn, Tr, Gs, RWC, and MSI, with increases of 98.8, 393, 136, 185, 188, 86.4, and 98.3%, respectively, compared to untreated plants (Table 1). In contrast, the Kh treatment alone produced the lowest values for all traits, except for the control treatment (no addition) (Table 1).

Impact of biostimulants and/or organic amendments on the biochemical components of plants

Our results showed that the addition of all organic amendments significantly increased the plant contents of chlorophyll a and b, carotenoids, and proline compared to the absence of organic amendments (Table 2). These traits increased by 57.6, 18.2, 41.3, and 39.0%, respectively, with vermicompost application; by 25.5, 2.53, 23.4, and 21.0%, respectively, with compost application, and by 39.0, 8.77, 31.6, and 29.2%, respectively, with CM application, compared to the control treatment (Table 2).

Vermicompost treatment significantly enhanced these traits by 25.5, 15.3, 14.6, and 14.8%, respectively, compared to compost treatment, and by 13.4, 8.68, 7.40, and 7.57%, respectively, compared to CM treatment (Table 2). Furthermore, CM application significantly increased all these attributes by 10.8, 6.09, 6.67, and 6.74%, respectively, relative to compost application. Significant and positive effects of all biostimulants on these traits compared to untreated plants were also observed (Table 2). The highest plant contents of these traits were noted with MLE application, followed by LRE, GRE, and Kh, respectively (Table 2).

Compared to the control treatment, these traits increased significantly by 112.0, 52.5, 57.0, and 40.3% in response to MLE application; by 76.0, 36.1, 46.2, and 34.5% in response to LRE; by 46.3, 22.7, 33.4, and 20.2% in response to GRE application, and by 18.4, 10.4, 19.0, and 9.38% in response to Kh application, respectively (Table 2). MLE application significantly enhanced these attributes by 20.4–79.0, 12.1–38.2, 7.36–31.9, and 4.29–28.2%, respectively, compared to other biostimulants (Table 2).

The interaction between organic amendments and biostimulants also significantly impacted these attributes. The greatest increase in chlorophyll a and b, carotene, and proline were observed with the combined application of vermicompost and MLE, which increased these traits by 229, 109, 131, and 91.6%, respectively, compared to the untreated plants (Table 2).

Impact of biostimulants and/or organic amendments on antioxidant enzyme activities

The results indicated that the addition of all organic amendments significantly enhanced the plant levels of CAT, POX, and SOD compared to the absence of organic amendments (Table 2). For instance, CAT, POX, and SOD levels increased significantly by 28.8, 37.9, and 59.5%, respectively, with vermicompost application; by 8.19, 13.6, and 30.0%, respectively, with compost application, and by 14.1, 27.2, and 43.2%, respectively with CM application. Vermicompost treatment significantly increased CAT, POX, and SOD, by 19.1, 21.4, and 22.7%, respectively, compared to compost treatment, and by 13.0, 8.40, and 11.3%, respectively, compared to CM treatment.

Moreover, CM application significantly increased CAT, POX, and SOD by 5.43, 12.0, and 10.2%, respectively, compared to compost application. All biostimulants showed significant and positive effects on increasing CAT, POX, and SOD compared to untreated plants. The highest levels of CAT, POX, and SOD were observed with MLE application, followed by LRE, GRE, and Kh, respectively (Table 2).

Compared to the control, CAT, POX, and SOD increased significantly by 32.6, 44.6, and 70.6%, respectively, in response to MLE application; by 22.6, 34.7, and 51.8%, respectively, in response to LRE, by 15.5, 20.8, and 33.3%, respectively, in response to GRE application; and by 7.83, 9.90, and 13.4%, respectively, in response to Kh application (Table 2).

The application of MLE enhanced CAT, POX, and SOD by 8.11–22.9, 7.35–31.5, and 12.4–50.5%, respectively, compared to other biostimulants (Table 2). The interaction between organic amendments and biostimulants also significantly affected CAT, POX, and SOD activities. The greatest increases in CAT (63.9%), POX (95.1%), and SOD (185%) activities were observed with the combined application of vermicompost and MLE (Table 2).

Impact of biostimulants and/or organic amendments on nutrient uptake

The addition of organic amendments significantly increased N, P, and K uptake while significantly reduced Na uptake in both straw and grains (Table 3). Wheat plants treated with vermicompost showed the highest N, P, and K uptake in straw and grains, followed by those treated with CM, and compost, compared to untreated plants (Table 3). In contrast, the highest values of Na uptake in both straw and grains were observed in the control treatment (no amendment addition). However, Na uptake decreased in both straw and grains with the addition of organic amendments, with the lowest values recorded for vermicompost, followed by CM, and compost, respectively (Table 3).

Regarding the individual effect of biostimulants on N, P, and K uptake, the foliar application of MLE was the most effective treatment, followed by LRE, GRE, and Kh, respectively, compared to the control treatment (without foliar application) (Table 3). This trend was consistent for N, P, and K uptake in both straw and grains (Table 3).

On the other hand, the lowest values of Na uptake in both straw and grains were observed in wheat plants sprayed with MLE, while the highest values were found in unsprayed plants (Table 3). Concerning the interaction among treatments studied, the highest N, P, and K uptake was observed in wheat plants treated with vermicompost and sprayed with MLE, while the lowest values were recorded in the control treatment (without soil and foliar applications) (Table 3).

Conversely, the highest Na uptake values were found in untreated plants, while the combination of soil organic amendments and foliar applications significantly reduced Na uptake. The lowest Na uptake values were recorded in wheat plants treated with vermicompost and sprayed with MLE (Table 3).

Effect of organic amendments and/or biostimulants on wheat yield and its components

The addition of organic amendments significantly increased spike lengths and weights, the weight of 1000 grains, the number of grains/spike, grain yield, straw yield, biological yield, and harvest index compared to the control treatment (Table 4). Wheat plants grown on salt-affected soil and amended with vermicompost exhibited the highest values of these attributes, followed by those amended with CM, and compost, while untreated plants showed the lowest values (Table 4).

Compared to the control treatment, vermicompost addition increased the aforementioned traits by 13.7, 45.2, 6.60, 10.8, 28.0, 12.5, 18.4, and 7.94%, respectively (Table 4). Vermicompost also increased these traits by 6.35, 18.3, 2.41, 5.20, 13.2, 5.63, 8.64, and 4.25%, respectively, compared to compost addition, and by 2.56, 6.41, 1.43, 1.90, 5.01, 1.89, 3.16, and 1.85% compared to the addition of CM (Table 4).

Foliar application of biostimulants also resulted in significant increases in these attributes compared to the control. Plants sprayed with MLE had the highest values, followed by those treated with LRE, GRE, and Kh, respectively, while untreated plants had the lowest values of all yield traits (Table 4). The MLE foliar spray increased these traits by 20.4, 70.3, 9.02, 15.4, 39.9, 18.1, 26.3, and 10.6%, respectively compared to the control treatment, by 20.9, 2.54, 6.10, 14.4, 7.00, 10.1, and 4.17% compared to the LRE treatment, and by 11.9, 36.7, 4.702, 9.81, 24.3, 11.0, 16.2, and 6.95% compared to the Kh treatment (Table 4).

Wheat plants treated with vermicompost before sowing and sprayed with MLE achieved the highest values of these attributes, while untreated plants (without soil and foliar applications) recorded the lowest values (Table 4).

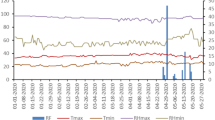

PCA and correlation analysis

The PCA ordination plot illustrated the relationships among the studied attributes (Fig. 1). The first (PC-1), and second (PC-2) ordination axes explained 88.8% and 6.99% of the total variations, respectively. Strong positive correlations were observed among total chlorophyll content, grain yield, proline content, SOD, CAT, and N, P, and K uptake (Fig. 1). In addition, we found high correlations between leaf area and both Tr and Pn. A negative correlation was recorded between Na uptake and all other studies variables (Fig. 1).

Bi-plot revealing the first two variables of the principal component (PC1 and PC2). V, vermicompost, C, compost; CM, chicken manure; MLE, moringa leaf extract; LRE, licorice root extract; GRE, ginger rhizome extract; Kh, potassium humate; CAT, catalase enzyme activity; SOD, superoxide dismutase; Pn, leaf net photosynthetic rate; Tr, transpiration rate; N, nitrogen; P, phosphorus; K, potassium; Na, sodium.

The Pearson’s correlation matrix also revealed significant positive correlations among all studied variables, except for Na uptake, which exhibited a significant negative correlation with all studied variables (Fig. 2).

Pearson’s correlation showing the relationship among plant parameters. Pn, leaf net photosynthetic rate; Tr, transpiration rate; Gs, stomatal conductance; RWC, relative water content; MSI, membrane stability index; CAT, catalase enzyme activity; POX, peroxidase activity; SOD, superoxide dismutase; N, nitrogen; P, phosphorus; K, potassium; Na, sodium.

Discussion

Plants can be exposed to multiple natural stresses simultaneously, such as salinity and alkalinity. Many saline soils have alkaline pH, so plants growing on these conditions often face both salinity and alkalinity stress70,71. Wheat, in particular, shows notable tolerance to salt72. However, soil salinity reduces the ability of plant roots to absorb water, which adversely affects plant growth73. The disruption in the metabolic process, leading to decreased meristematic activity and cell extension, is correlated with increased respiration rates in plants grown in salt-affected soils, which require a significant amount of energy73,74.

In response to salinity stress, plants produce ROS like H2O2, O2•−, and OH−14. The generation of ROS causes oxidative stress, damaging chlorophyll, DNA, membrane functions, and proteins75. To combat this, plants have evolved complex antioxidant systems to repair and mitigate ROS damage76. These antioxidant systems include various enzymes and non-enzyme compounds, such as proline, carotene, and ascorbic acid, which are low in molecular weight77,78.

In the current study, wheat plants grown under soil salinity conditions showed significant reductions in growth and yield. However, the use of LRE, MLE, GRE, and Kh as foliar sprays, combined with compost, CM, and vermicompost, helped alleviate the adverse effects of these stresses. The distinct chemical compositions of LRE, MLE, and GRE suggest their potential as biostimulants in enhancing plant growth and yield19.

Previous research has demonstrated that LRE, MLE, and GRE contain essential macro-elements (N, P, K, Ca, and Mg), microelements (Zn, Cu, and Fe), several amino acids, proline, and Se19,20. The application of LRE, MLE, and GRE under saline soil conditions in the present study may promote faster plant growth by increasing plant height, leaf number, leaf area, and dry weight. This improvement may result from the increased mobilization of germination-linked metabolites and dissolved substances, such as N, P, K, and Ca.

It has also been demonstrated that amino acids present in LRE, MLE, and GRE contribute to increased sugar content, enzyme activity, and plant growth79,80. Furthermore, the production of wheat plants grown under soil-saline conditions significantly increased when gibberellin and Se, which are components of LRE, were added81,82. Previous studies have also found that gibberellin applications increased plant dry weight and leaf area under saline conditions83,84. Analytical analysis of LRE, MLE, and GRE extracts revealed that these extracts contain beneficial antioxidants, such as proline, ascorbic acid, soluble sugars, and phytohormones (e.g., indol-3-acetic acid and cytokinin)23,85,86. The current study demonstrated that LRE, MLE, and GRE enhanced growth parameters, likely due to the heightened release of inorganic solutes and germination-related metabolites, including zeatin and indol-3-acetic acid, which promote germination.

In addition, the increased activity of amylase enzymes and reducing sugars associated with water absorption and increased cell elongation resulted in enhanced plant growth86. These findings are consistent with previous studies14,79,80 that reported the positive effect of moringa seed extract and LRE on plant production and defense systems under stress conditions. These effects may be attributed to the improved mobilization of germination and growth-related metabolites, dissolved substances such as mineral nutrients, soluble sugars, antioxidants, and amino acids of moringa seed extract and LRE, which contribute to early seed activities, and positively impact seedling growth.

Moreover, humic substances have both direct and indirect influences on plant growth87. By improving soil properties and structure, humic substances indirectly enhance plant growth, leading to increased soil fertility, as previously reported88. They also directly affect plant tissues through processes related to their uptake and transport89. The induction of carbon and N metabolism by humic substances further enhances plant growth and development. By improving root architecture and altering mineral uptake, humic compounds can potentially mitigate the adverse effects of Na stress90,91.

Humic substances promote plant growth and development through interactions with signal transduction cascades and membrane transporters responsible for nutrient uptake91. Nardi et al89. also noted that humic substances could reduce the pH of the cell wall by catalyzing H+-ATPase in the plasma membrane compartments of the roots. This process helps maintain turgor pressure during cell elongation, which activates cell expansion by promoting ion uptake89.

Certain auxin-like molecules present in humic substances may regulate root growth and proton pump activation91. Humic substances may exert biological activity via cellular receptors on root surfaces upon releasing small fractions into the rhizosphere92. These results are in line with previous findings93,94 that reported an increase in plant growth and nutrients uptake under salinity stress condition following the application of humic acid.

Vermicompost has a superior effect due to its elevated microbial activity, which is induced by actinobacteria, fungi, bacteria, yeasts, and algae. These microorganisms generate growth regulators, including auxins, gibberellins, and cytokinins, which can benefit plant growth and development. In addition, vermicompost contains humic substances that enhance the availability of N, P, K, and Zn for the synthesis of tryptophan, a precursor to auxins that promote plant growth and root development95. These findings align with previous research27,96, which demonstrated that vermicompost positively impacts the fresh and dry biomass of maize roots and shoots under salinity stress27,96.

Incorporating CM as fertilizer increases the soil’s concentration of water-soluble minerals. CM is preferred not only for its high concentration of macronutrients but also for its high CEC, a large exchangeable base pool, and significant contributions to N and P97. However, CM with a high pH can hinder nitrification, either immediately or after a lag period, leading to the loss of N i.e., NO3[–98. Previous studies have shown significant yield differences between experimental and control groups after adding CM composts95.

Leaf photosynthesis was maximized by maintaining green leaf areas (Table 1) and reducing sink capacity through the supply of photo assimilates from leaves. Thomas and Howarth99reported similar findings. Furthermore, PSII functional activity can be used to assess a plant’s photosynthetic ability. Research indicates that salinity stress structurally and functionally damages electron carriers and photosystems, particularly PSII. Long-term exposure to high salt stress often leads to structural damage in PSII100. The application of LRE, MLE, GRE, Kh, vermicompost, compost, and CM in the current study helped maintain Pn, Tr, Gs, and chlorophyll concentrations (Tables 1 and 2).

A previous study also indicated a significant increase in leaf area with the application of LRE at 2.0 g L−1, and a notable increase in chlorophyll concentration with 4.0 g L−1 LRE98. Gibberellins and nutrients in MLE, GRE, and LRE were found to inhibit senescence in the early stages of leaf development, maintaining a high leaf area and increasing photosynthetic pigments14,17.

The enhancement in growth rate induced by gibberellin may stimulate cell division and elongation, thereby increasing leaf area and photosynthetic rates80. Meanwhile, MLE, GRE, and LRE contain iron (Fe), which plays an important role in activating chlorophyll biosynthesis enzymes, as well as chlorophyll-protecting antioxidant enzymes such as APOX and GSH, which release ROS101. Furthermore, stomatal regulation is crucial in controlling the rate of photosynthesis in plants grown in saline environments102,103. This regulation may be due to the role of K in maintaining high tissue water content under stress conditions, as it acts as a major osmotic agent in vacuoles104. The availability of K within guard cells and leaf apoplasts is essential for stomatal regulation105. K is a key determinant of photosynthesis, primarily by regulating stomatal activity106.

Growing plants under salt stress has been shown to increase growth characteristics, chlorophyll content, and the number and yield of fruits. This improvement may be attributed to a higher level of assimilation, which is correlated with the content of macro- and micro-nutrients, gibberellin and Se79,107. These findings are consistent with previous studies15,22,108.

Available evidence suggests that MLE prevents early leaf senescence, leading to increased leaf area and higher concentrations in photosynthetic compounds109. The application of MLE, GRE, and LRE has been shown to improve chlorophyll concentrations due to the delayed onset of mineral nutrients, phytohormones (particularly cytokinins), and antioxidants present in MLE, GRE, and LRE, which delay leaf senescence110. Humic substances facilitate respiration and photosynthesis through modifications in mitochondrial and chloroplast functions89. Consequently, humic acid can mitigate the negative effects of abiotic stresses on plants111.

In addition, humic compounds have been found to enhance the activity of the enzyme invertase, which hydrolyzes sucrose into hexose for cell growth112. The findings help explain the observed increases in net photosynthetic rate, Tr, Gs, and chlorophyll-rich leaves actively engaged in photosynthesis.

Wheat plants were adversely affected by reduced RWC due to stress, as water flow from roots to shoots was diminished. However, water uptake was significantly increased when bio-stimulants such as LRE, MLE, GRE, Kh, compost, CM, and/or vermicompost were applied to saline soils. This increase in water uptake corresponded with an enhancement of RWC. Maintaining RWC at optimal levels in cells and tissues supports metabolic activity through adaptations to salinity and osmotic adjustments113.

It was observed that saline soil decreased RWC; however, supplementation with LRE, MLE, GRE, and Kh and/or vermicompost, compost, and CM alleviated water stress by increasing water use efficiency. Under stress conditions, increased RWC was observed when biostimulants were applied114. In addition, these biostimulants reduced transpiration rates by depositing in leaf and stem epidermal cells, which also increased K absorption and its translocation to stomatal guard, thereby influencing stomatal conductivity115. These findings align with previous studies15,116, which reported that foliar spray with different plant extracts increases RWC and MSI under salinity stress conditions.

Compared to control plants, wheat plants treated with LRE, MLE, GRE, and Kh and/or vermicompost, compost and CM showed higher RWC than those in the control treatments. Consistent with previous research, the current study demonstrated a significant decrease in RWC under stress conditions (Table 1). However, the application of these bio-stimulants restored RWC levels to those observed in non-stressed wheat plants117. Furthermore, stress was found to reduce the MSI118. In terms of increasing MSI, the application of bio-stimulants reduced the permeability of the plasma membrane in leaf cells (Table 1).

Plants subjected to salinity can undergo osmotic adjustment due to alterations in proline levels. In general, plant response to salt stress may involve the accumulation of proline119. Elevated proline levels in salt-stressed plants result from acclimation, providing the plant with the energy required for survival and growth, thereby enhancing the plant’s capacity to withstand stress120. In many plant species, proline accumulation can constitute up to 20% of the amino acid pool under normal conditions but it may increase to 80% under stress conditions, resulting from both increased synthesis and reduced degradation121. Free proline enhances plant tolerance and mitigates ROS damage by detoxifying ROS produced by salinity toxicity. Singlet oxygen may be physically quenched by free proline or directly react with hydroxyl radicals108.

The present study demonstrated an increase in total proline with a single treatment or a combination of LRE, MLE, GRE, and Kh and/or vermicompost, compost, and CM. In response to the increase in proline, the antioxidant system in plants was strengthened, preventing damage from salt stress122. These results align with those of previous studies16,116,123,124.

Salt stress induces oxidative damage in cells due alterations in antioxidant activity and an imbalance in ROS production125. Plants possess several antioxidant systems that mitigate oxidative damage caused by salt stress. Among these are enzymes such as SOD, which is considered the first line of defense against ROS, reducing the O2•− radical to H2O2126. H2O2 serves as the substrate for CAT, which are located in peroxisomes where H2O2 concentration is high but absent in the cytosol and chloroplasts; thus, peroxidases eliminate H2O2127. APX also plays a role in reducing ROS127,128. GSH and dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR), regenerative enzymes that use GSH reduced GSH as a reducing agent in the Halliwell–Asada cycle, facilitate the regeneration of ascorbic acid from dehydroascorbate (DHA)129. The present study revealed a significant increase in the activity of antioxidant enzymes CAT, POX, and SOD with all treatments compared to the control (Table 2). This was also true when combined treatments were applied.

With the application of LRE, MLE, GRE, and Kh and/or vermicompost, compost, and CM on plants grown in saline soil, the concentration of Na increased, accompanied by a reduction of N, P, and K (Fig. 2). Our biostimulants have demonstrated an ability to enhance nutrient uptake, thereby improving nutrient status. A direct correlation exists between the activity of membrane carriers and the maintenance of nutrient homeostasis in plants, which are responsible for transferring ions from the soil to the plant and regulating ion distribution among cells130. This regulation can be disrupted when Na ions compete with N, P, and K across membranes, especially under stress conditions. These disruptions indicate a nutrient deficiency in plants131.

The positive effect of our biostimulants application on the instability of K in the cytosol due to salt stress was evident132, as it maintained elevated levels of K and a proper K/Na ratio in plants. This balance is a fundamental mechanism for coping with salt stress, as shown in the current study133.

The findings of the current study will enable us to make more accurate estimates of the wheat defense system’s response to the integrative application of organic amendments (e.g. vermicompost, compost, CM) and biostimulants (e.g. LRE, MLE, GRE, Kh). Ultimately, this could improve wheat yield and quality under salt-alkali stress.

However, it remains unclear which specific compounds in the biostimulants are responsible for enhancing wheat plants’ growth and defense systems under such conditions. Moreover, recent studies suggest that plant extracts (i.e., MLE) may have direct or indirect effects on plant gene expression. Therefore, further research is urgently needed to assess the impact of specific biostimulants compounds on the gene expression and defense systems of wheat plants under salt-alkali stress conditions.

Conclusions

The present study indicates that applying LRE, MLE, GRE, and Kh and/or vermicompost, compost, and CM significantly increased grain and straw yields under salt-alkali stress. This was evidenced by higher levels of chlorophyll and proline, photosynthetic pigments, enhanced water uptake, improved stomatal conductance, and greater enzyme activities. Compared to the control treatment, uptake of N, P, and K increased significantly in response to organic amendments alone or in combination with bio-stimulants, whereas Na uptake decreased. Combining organic amendments with bio-stimulants, particularly vermicompost with MLE, yielded superior results. Therefore, co-application of organic amendments and natural bio-stimulants can be an effective strategy for maintaining plant productivity under saline soil stresses. However, further research is needed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of bio-stimulants and optimize their application in agricultural practices.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Reynolds, M. P., Pietragalla, J. & Braun, H. J. International symposium on wheat yield potential: Challenges to international wheat breeding (International maize and wheat improvement centre, México-Veracruz, Mexico, 2008).

Mabrouk, O., Fahim, M., Abd El Badeea, O. & Omara, R. The impact of wheat yellow rust on quantitative and qualitative grain yield losses under Egyptian field conditions. Egypt. J. Pathol. 50, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejp.2022.117996.1054 (2022).

Sadat Noori, S. A. & McNeilly, T. Assessment of variability in salt tolerance based on seedling growth in Triticum durum Desf. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 47, 285–291. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1008749312148 (2000).

Mansour, E. et al. Multidimensional evaluation for detecting salt tolerance of bread wheat genotypes under actual saline field growing conditions. Plants 9, 1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9101324 (2020).

Glick, B. R., Cheng, Z., Czarny, J. & Duan, J. Promotion of plant growth by ACC deaminase-producing soil bacteria. Eur. J. Plant. Pathol. 119, 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-007-9162-4 (2007).

Foyer, C. H., Rasool, B., Davey, J. W. & Hancock, R. D. Cross-tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: a focus on resistance to aphid infestation. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 2025–2037. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erw079 (2016).

Munns, R. Genes and salt tolerance: bringing them together. New Phytol. 167, 645–663. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01487.x (2005).

Nadeem, S. M. et al. Relationship between in vitro characterization and comparative efficacy of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria for improving cucumber salt tolerance. Arch. Microbiol. 198, 379–387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-016-1197-5 (2016).

Munns, R. & Tester, M. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 651–681. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092911 (2008).

Shi, Q., Ding, F., Wang, X. & Wei, M. Exogenous nitric oxide protect cucumber roots against oxidative stress induced by salt stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 45, 542–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2007.05.005 (2007).

Duarte, B., Santos, D., Marques, J. C. & Caçador, I. Ecophysiological adaptations of two halophytes to salt stress: photosynthesis, PS II photochemistry and anti-oxidant feedback – implications for resilience in climate change. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 67, 178–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.03.004 (2013).

Apel, K. & Hirt, H. Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 55, 373–399. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141701 (2004).

Siringam, K., Juntawong, N., Cha-um, S. & Kirdmanee, C. Salt stress induced ion accumulation, ion homeostasis, membrane injury and sugar contents in salt-sensitive rice (Oryza sativa L. spp. indica) roots under isoosmotic conditions. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 10, 1340–1346 (2011).

Desoky, E. S. M., Elrys, A. S. & Rady, M. M. Integrative moringa and licorice extracts application improves Capsicum annuum fruit yield and declines its contaminant contents on a heavy metals-contaminated saline soil. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 169, 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.10.117 (2019).

Semida, W. M. & Rady, M. M. Presoaking application of propolis and maize grain extracts alleviates salinity stress in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L). Sci. Hortic. 168, 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2014.01.042 (2014).

Rady, M. M. & Mohamed, G. F. Modulation of salt stress effects on the growth, physio-chemical attributes and yields of Phaseolus vulgaris L. plants by the combined application of salicylic acid and Moringa oleifera leaf extract. Sci. Hortic. 193, 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2015.07.003 (2015).

Desoky, E. S. M., Merwad, A. R. M. & Rady, M. M. Natural biostimulants improve saline soil characteristics and salt stressed-sorghum performance. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 49, 967–983. https://doi.org/10.1080/00103624.2018.1448861 (2018).

Elrys, A. S., Merwad, A. R. M. A., Abdo, A. I. E., Abdel-Fatah, M. K. & Desoky, E. S. M. Does the application of silicon and moringa seed extract reduce heavy metals toxicity in potato tubers treated with phosphate fertilizers? Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 225, 16776–16787. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-1823-7 (2018).

Elrys, A. & Merwad, A. R. Effect of alternative spraying with silicate and licorice root extract on yield and nutrients uptake by pea plants. Egypt. J. Agron. 39, 279–292. https://doi.org/10.21608/agro.2017.1429.1071 (2017).

Abulfaraj, A. A. Stepwise signal transduction cascades under salt stress in leaves of wild barley (Hordeum spontaneum). Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 34, 860–872. https://doi.org/10.1080/13102818.2020.1807408 (2020).

Desoky, E. S. M. et al. Foliar supplementation of clove fruit extract and salicylic acid maintains the performance and antioxidant defense system of Solanum tuberosum L. under deficient irrigation regimes. Horticulturae 7, 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7110435 (2021).

Eltahawy, A. M. A. E., Awad, E. S. A. M., Ibrahim, A. H., Merwad, A. R. M. A. & Desoky, E. S. M. Integrative application of heavy metal-resistant bacteria, moringa extracts, and nano-silicon improves spinach yield and declines its contaminant contents on a heavy metal-contaminated soil. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1019014–1019014. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.1019014 (2022).

Rady, M. M. & Hemida, K. A. Modulation of cadmium toxicity and enhancing cadmium-tolerance in wheat seedlings by exogenous application of polyamines. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 119, 178–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.05.008 (2015).

Hamed, F. R., Ismail, H. E. M., El-Maati, M. A. & Desoky, E. M. Effect of vermicompost-tea and plant extracts on growth, physiological, and biochemical traits of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L). SABRAO J. Breed. Genet. 54, 1202–1215. https://doi.org/10.54910/sabrao2022.54.5.21 (2022).

Bidabadi, S. S. Waste management using vermicompost derived liquids in sustainable horticulture. Trends Hortic. 1, 175. https://doi.org/10.24294/th.v1i3.175 (2018).

Abbott, L. K. et al. Potential roles of biological amendments for profitable grain production – A review. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 256, 34–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.12.021 (2018).

Alamer, K. H. et al. Mitigation of salinity stress in maize seedlings by the application of vermicompost and sorghum water extracts. Plants 11, 2548. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11192548 (2022).

García, A. C. et al. L. Vermicompost humic acids as an ecological pathway to protect rice plant against oxidative stress. Ecol. Eng. 47, 203–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2012.06.011 (2012).

Shilev, S. Plant-growth-promoting bacteria mitigating soil salinity stress in plants. Appl. Sci. 10, 7326. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10207326 (2020).

Ravindran, B., Wong, J. W. C., Selvam, A. & Sekaran, G. Influence of microbial diversity and plant growth hormones in compost and vermicompost from fermented tannery waste. Bioresour. Technol. 217, 200–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2016.03.032 (2016).

Amooaghaie, R. & Golmohammadi, S. Effect of vermicompost on growth, essential oil, and health of Thymus Vulgaris. Compost Sci. Util. 25, 166–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/1065657x.2016.1249314 (2017).

Srivastava, P. K., Gupta, M., Shikha, Singh, N. & Tewari, S. K. Amelioration of sodic soil for wheat cultivation using bioaugmented organic soil amendment. Land Degrad. Dev. 27, 1245–1254. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.2292 (2014).

Lax, A., Diaz, E., Castillo, V. & Albaladejo, J. Reclamation of physical and chemical properties of a salinized soil by organic amendment. Arid Land Res. Manag. 8, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/15324989309381374 (1993).

Chaganti, V. N., Crohn, D. M. & Šimůnek, J. Leaching and reclamation of a biochar and compost amended saline–sodic soil with moderate SAR reclaimed water. Agric. Water Manag. 158, 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2015.05.016 (2015).

Mahmoodabadi, M., Yazdanpanah, N., Sinobas, L. R., Pazira, E. & Neshat, A. Reclamation of calcareous saline sodic soil with different amendments (I): redistribution of soluble cations within the soil profile. Agric. Water Manag. 120, 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2012.08.018 (2013).

Diacono, M. & Montemurro, F. Effectiveness of organic wastes as fertilizers and amendments in salt-affected soils. Agriculture 5, 221–230. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture5020221 (2015).

Van Oosten, M. J., Pepe, O., De Pascale, S., Silletti, S. & Maggio, A. The role of biostimulants and bioeffectors as alleviators of abiotic stress in crop plants. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40538-017-0089-5 (2017).

Puglisi, E. et al. Rhizosphere microbial diversity as influenced by humic substance amendments and chemical composition of rhizodeposits. J. Geochem. Explor. 129, 82–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gexplo.2012.10.006 (2013).

Noroozisharaf, A. & Kaviani, M. Effect of soil application of humic acid on nutrients uptake, essential oil and chemical compositions of garden thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.) under greenhouse conditions. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 24, 423–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12298-018-0510-y (2018).

Kaya, C., Akram, N. A., Ashraf, M. & Sonmez, O. Exogenous application of humic acid mitigates salinity stress in maize (Zea mays L.) plants by improving some key physico-biochemical attributes. Cereal Res. Commun. 46, 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1556/0806.45.2017.064 (2018).

Ali, A. Y. A. et al. Ameliorative effects of jasmonic acid and humic acid on antioxidant enzymes and salt tolerance of forage sorghum under salinity conditions. Agron. J. 111, 3099–3108. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2019.05.0347 (2019).

Reis de Andrade et al. K-Humate as an agricultural alternative to increase nodulation of soybeans inoculated with Bradyrhizobium. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 36, 102129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2021.102129 (2021).

Abdelrasheed, K. G. et al. Soil amendment using biochar and application of K-Humate enhance the growth, productivity, and nutritional value of onion (Allium cepa L.) under deficit irrigation conditions. Plants 10, 2598. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10122598 (2021).

Mridha, D. et al. Rice seed (IR64) priming with potassium humate for improvement of seed germination, seedling growth and antioxidant defense system under arsenic stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 219, 112313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112313 (2021).

Kumari, S. et al. A track to develop salinity tolerant plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 167, 1011–1023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.09.031 (2021).

Taha, S. S. & Osman, A. S. Influence of potassium humate on biochemical and agronomic attributes of bean plants grown on saline soil. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 93, 545–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/14620316.2017.1416960 (2017).

Yasmeen, A. Exploring the potential of moringa (Moringa oleifera) leaf extract as natural plant growth enhancer. (Doctor of Philosphy in Agronomy, Department of Agronomy Faculty of Agriculture, University Of Agriculture, Faisalabad, Pakistan, 2011).

Ghazi, D. Response of hot pepper plants (Capsicum frutescens L.) to compost and some foliar application treatments. J. Soil. Sci. Agric. Eng. 11, 641–646. https://doi.org/10.21608/jssae.2020.135692 (2020).

Doklega, S. & Imryed, Y. Effect of vermicompost and nitrogen levels fertilization on yield and quality of head lettuce. J. Plant Prod. 11, 1495–1499. https://doi.org/10.21608/jpp.2020.149823 (2020).

Elrys, A. S., Abdo, A. I. E., Abdel-Hamed, E. M. W. & Desoky, E. S. M. Integrative application of licorice root extract or lipoic acid with fulvic acid improves wheat production and defenses under salt stress conditions. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 190, 110144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.110144 (2020).

Othman, M. Effect of organic fertilizers and foliar application of some stimulants on barley plants under saline condition. J. Soil Sci. Agric. Eng. 12, 279–287. https://doi.org/10.21608/jssae.2021.171531 (2021).

Ghazi, D. & El-Sherpiny, M. Improving performance of maize plants grown under deficit water stress. J. Soil Sci. Agric. Eng. 12, 725–734. https://doi.org/10.21608/jssae.2021.206554 (2021).

Sarkar, D. & Haldar, A. Physical and chemical methods in soil analysis: fundamental concepts of analytical chemistry and instrumental techniques. 193 p. (New Age International, New Delhi, India, 2005).

El-Hammady, A., Abo–Hadid, A., Selim, S. M., El–Kassas, H. & Negm, R. Production of compost from rice straw using different accelerating amendments. J. Environ. Sci. Ain Shams Univ. 6, 112–116 (2003).

Mvumi, C., Tagwira, F. & Chiteka, A. Z. Effect of moringa extract on growth and yield of maize and common beans. Greener J. Agric. Sci. 3, 055–062. https://doi.org/10.15580/gjas.2013.1.111512264 (2013).

Zia-ur‐Rehman, Salariya, A. M. & Habib, F. Antioxidant activity of ginger extract in sunflower oil. J. Sci. Food Agric. 83, 624–629. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.1318 (2003).

Avron, M. Photophosphorylation by swiss-chard chloroplasts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 40, 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3002(60)91350-0 (1960).

Barrs, H. D. & Weatherley, P. E. A re-examination of the relative turgidity technique for estimating water deficits in leaves. Aust J. Biol. Sci. 15, 413. https://doi.org/10.1071/bi9620413 (1962).

Premachandra, G. S., Saneoka, H. & Ogata, S. Cell membrane stability, an indicator of drought tolerance, as affected by applied nitrogen in soyabean. J. Agric. Sci. 115, 63–66. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021859600073925 (1990).

Bates, L. S., Waldren, R. P. & Teare, I. D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 39, 205–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00018060 (1973).

Wolf, B. A comprehensive system of leaf analyses and its use for diagnosing crop nutrient status. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 13, 1035–1059. https://doi.org/10.1080/00103628209367332 (1982).

Lachica, M., Aguilar, A. & Yañez, J. Foliar analysis: Analytical methods used in the Estacion Experimental Del Zaidin. Edafol Agribiol. 32, 1033–1047 (1973).

Chapman, H. D. & Pratt, P. F. Methods of analysis for soils, plants and waters. Soil Sci. 93, 68. https://doi.org/10.1097/00010694-196201000-00015 (1962).

Watanabe, F. S. & Olsen, S. R. Test of an ascorbic acid method for determining phosphorus in water and NaHCO3 extracts from soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 29, 677–678. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1965.03615995002900060025x (1965).

Mukherjee, S. P. & Choudhuri, M. A. Implications of water stress-induced changes in the levels of endogenous ascorbic acid and hydrogen peroxide in Vigna seedlings. Physiol. Plant. 58, 166–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3054.1983.tb04162.x (1983).

Aebi, H. Catalase in vitro. In Methods in Enzymology. Oxygen Radicals in Biological Systems. (Eds). L. Packer. 105, 121–126. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands. (1984).

Giannopolitis, C. N. & Ries, S. K. Superoxide dismutases: I. occurrence in higher plants. Plant Physiol. 59, 309–314. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.59.2.309 (1977).

Maehly, A. C. The assay of catalases and peroxidases. Methods Biochem. Anal. 1, 357-424. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470110171.ch14 (1954).

Klapheck, S., Zimmer, I. & Cosse, H. Scavenging of hydrogen peroxide in the endosperm of Ricinus communis by ascorbate peroxidase. Plant Cell Physiol. 31, 1005–1013. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a077996 (1990).

Mali, V., Zende, N. & Verma, U. Correlation between soil physico-chemical properties and available micronutrients in salt affected soils. 17th World Congress of Soil Science, Aug 14–21. Thailand. Symposium number 33, paper number 2220. (2002). (2002).

Biswas, A. & Biswas, A. Comprehensive approaches in rehabilitating salt affected soils: A review on Indian perspective. Open Trans. Geosci. 2014, 13–24. https://doi.org/10.15764/geos.2014.01003 (2014).

Higuchi, K. et al. Nicotianamine synthase gene expression differs in barley and rice under Fe-deficient conditions. Plant J. 25, 159–167. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.00951.x (2001).

Kaydan, D., Yagmur, M. & Okut, N. Effects of salicylic acid on the growth and some physiological characters in salt stressed wheat (Triticum aestivum L). Tarım Bilimleri Dergisi. 13, 114–119. https://doi.org/10.1501/tarimbil_0000000444 (2007).

Qados, A. & Moftah, A. Influence of silicon and nano-silicon on germination, growth and yield of faba bean (Vicia faba L.) under salt stress conditions. Am. J. Exp. Agric. 5, 509–524. https://doi.org/10.9734/ajea/2015/14109 (2015).

Cheeseman, J. M. Hydrogen peroxide and plant stress: a challenging relationship. Plant Stress 1, 4–15 (2007).

Rady, M. M., Desoky, E. S. M., Elrys, A. S. & Boghdady, M. S. Can licorice root extract be used as an effective natural biostimulant for salt-stressed common bean plants? Afr. J. Bot. 121, 294–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2018.11.019 (2019).

Schutzendubel, A. Plant responses to abiotic stresses: heavy metal-induced oxidative stress and protection by mycorrhization. J. Exp. Bot. 53, 1351–1365. https://doi.org/10.1093/jexbot/53.372.1351 (2002).

Sitohy, M. Z., Desoky, E. S. M., Osman, A. & Rady, M. M. Pumpkin seed protein hydrolysate treatment alleviates salt stress effects on Phaseolus vulgaris by elevating antioxidant capacity and recovering ion homeostasis. Sci. Hortic. 271, 109495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109495 (2020).

Yildirim, E., Karlidag, H. & Turan, M. Mitigation of salt stress in strawberry by foliar K, ca and mg nutrient supply. Plant Soil Environ. 55, 213–221. https://doi.org/10.17221/383-pse (2009).

Nikee, E., Pazoki, A. & Zahedi, H. Influences of ascorbic acid and gibberellin on alleviation of salt stress in summer savory (Satureja hortensis L). Int. J. Biosci. 5, 245–255 (2014).

Mona, I. N., Gawish, S. M., Taha, T. & Mubarak, M. Response of wheat plants to application of selenium and humic acid under salt stress conditions. Egypt. J. Soil Sci. 57, 175–187. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejss.2017.3715 (2017).

Magome, H., Yamaguchi, S., Hanada, A., Kamiya, Y. & Oda, K. The DDF1 transcriptional activator upregulates expression of a gibberellin-deactivating gene, GA2ox7, under high‐salinity stress in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 56, 613–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313x.2008.03627.x (2008).

Maggio, A., Barbieri, G., Raimondi, G. & De Pascale, S. Contrasting effects of GA3 treatments on tomato plants exposed to increasing salinity. J. Plant Growth Regul. 29, 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-009-9114-7 (2009).

Elrys, A. S. et al. Can secondary metabolites extracted from Moringa seeds suppress ammonia oxidizers to increase nitrogen use efficiency and reduce nitrate contamination in potato tubers? Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 185, 109689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.109689 (2019).

Elrys, A. S. et al. Mitigate nitrate contamination in potato tubers and increase nitrogen recovery by combining dicyandiamide, moringa oil and zeolite with nitrogen fertilizer. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 209, 111839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111839 (2021).

Afzal, I., Hussain, B., Basra, S. M. A. & Rehman, H. Priming with moringa leaf extract reduces imbibitional chilling injury in spring maize. Seed Sci. Technol. 40, 271–276. https://doi.org/10.15258/sst.2012.40.2.13 (2012).

Cimrin, K. M. & Yilmaz, I. Humic acid applications to lettuce do not improve yield but do improve phosphorus availability. Acta Agric. Scand. B Soil Plant Sci. 55, 58–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/09064710510008559 (2005).

Sharif, M., Khattak, R. A. & Sarir, M. S. Effect of different levels of lignitic coal derived humic acid on growth of maize plants. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 33, 3567–3580. https://doi.org/10.1081/css-120015906 (2002).

Nardi, S., Pizzeghello, D., Muscolo, A. & Vianello, A. Physiological effects of humic substances on higher plants. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 34, 1527–1536. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0038-0717(02)00174-8 (2002).

Paksoy, M., Türkmen, Ö. & Dursun, A. Effects of potassium and humic acid on emergence, growth and nutrient contents of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.) seedling under saline soil conditions. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 9, 5343–5346 (2010).

Canellas, L. P. et al. Humic and fulvic acids as biostimulants in horticulture. Sci. Hortic. 196, 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2015.09.013 (2015).

Canellas, L. P. et al. Chemical composition and bioactivity properties of size-fractions separated from a vermicompost humic acid. Chemosphere 78, 457–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.10.018 (2010).

Khaled, H. & Fawy, H. A. Effect of different levels of humic acids on the nutrient content, plant growth, and soil properties under conditions of salinity. Soil Water Res. 6, 21. https://doi.org/10.17221/4/2010-SWR (2011).

Chen, Y., Clapp, C. & Magen, H. Mechanisms of plant growth stimulation by humic substances: the role of organo-iron complexes. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 50, 1089–1095. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380768.2004.10408579 (2004).

Indriyati, L. T. Chicken manure composts as nitrogen sources and their effect on the growth and quality of Komatsuna (Brassica rapa L). J. ISSAAS. 20, 52–63 (2014).

Beyk-Khormizi, A. et al. Ameliorating effect of vermicompost on Foeniculum vulgare under saline condition. J. Plant Nutr. 46, 1601–1615. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904167.2022.2092513 (2023).

Dikinya, O. & Mufwanzala, N. Chicken manure-enhanced soil fertility and productivity: effects of application rates. J. Soil Sci. Environ. 1, 46–54 (2010).

Khalil, I. M., Schmidhalter, U. & Gutser, R. Turnover of Chicken Manure in Some Upland Soils of Asia: Agricultural and Environmental Perspectives. In: Chicken manure treatment and application: CHIMATRA. Korner, I., Stegmann, R., Hassan, MN, Abdullah, AM, Huijsmans, J., Ogink, N.(eds.). Proceedings of The International Workshop from 19th to 20th January Hamburg, Germany. (2005).

Thomas, H. & Howarth, C. J. Five ways to stay green. J. Exp. Bot. 51, 329–337. https://doi.org/10.1093/jexbot/51.suppl_1.329 (2000).

Kalaji, H. M. et al. Chlorophyll a fluorescence as a tool to monitor physiological status of plants under abiotic stress conditions. Acta Physiol. Plant. 38, 102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11738-016-2113-y (2016).

Dawood, A. Effect of foliar spray of zinc and liquorice root extract on some vegetative and flowering growth parameters of two strawberry varieties (Fragaria x ananassa Duch). Mesop. J. Agric. 38, 152–151. https://doi.org/10.33899/magrj.2010.33653 (2010).

Zayed, B., Salem, A. & El Sharkawy, H. Effect of different micronutrient treatments on rice (Oriza Sativa L.) growth and yield under saline soil conditions. World J. Agric. Sci. 7, 179–184 (2011).

Athar, H. R. & Ashraf, M. Photosynthesis under Drought stress. In: Handbook of Photosynthesis. 2nd Ed (eds Pessarakli, M. & Dekker). Marcel and Taylor and Francis, Inc., New York, U.S.A. 793–809. (2005).

Marschner, H. Adaptation of plants to adverse chemical soil conditions. In Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants. (ed Marschner, H.) Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands 596–680. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012473542-2/50018-3 (1995).

Shabala, S., chimanski, S., Koutoulis, A. & L. J. & Heterogeneity in bean leaf mesophyll tissue and ion flux profiles: leaf electrophysiological characteristics correlate with the anatomical structure. Ann. Bot. 89, 221–226. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcf029 (2002).

Brugnoli, E. & Bjo¨rkman, O. Chloroplast movements in leaves: influence on chlorophyll fluorescence and measurements of light-induced absorbance changes related to ? pH and zeaxanthin formation. Photosynth Res. 32, 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00028795 (1992).

Yadavi, A., Aboueshaghi, R., Dehnavi, M. & Balouchi, H. Effect of micronutrients foliar application on grain qualitative characteristics and some physiological traits of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) under drought stress. Indian J. Fundam Appl. Life Sci. 4, 124–131 (2014).

Al-Taweel, S. K. et al. Abou-Sreea, A. I. Integrative seed and leaf treatment with ascorbic acid extends the planting period by improving tolerance to late sowing influences in parsley. Horticulturae 8, 334. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8040334 (2022).

Irshad, S., Matloob, A., Ghaffar, A., Hussain, M. B. & Nadeem Tahir, M. H. Agronomic and biochemical aspects of moringa dried leaf extract mediated growth and yield improvements in soybean. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/01140671.2024.2374066 (2024).

Elzaawely, A. A., Ahmed, M. E., Maswada, H. F. & Xuan, T. D. Enhancing growth, yield, biochemical, and hormonal contents of snap bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) sprayed with moringa leaf extract. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 63, 687–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/03650340.2016.1234042 (2016).

Gholami, H., Samavat, S. & Ardebili, Z. O. The alleviating effects of humic substances on photosynthesis and yield of Plantago ovate in salinity conditions. Int. Res. J. Basic. Appl. Sci. 4, 1683–1686 (2013).

Pizzeghello, D., Nicolini, G. & Nardi, S. Hormone-like activity of humic substances in Fagus sylvaticae forests. New Phytol. 151, 647–657. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0028-646x.2001.00223.x (2001).

Slabbert, M. M. & Krüger, G. H. J. Antioxidant enzyme activity, proline accumulation, leaf area and cell membrane stability in water stressed Amaranthus leaves. S. Afr. J. Bot. 95, 123–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2014.08.008 (2014).

Rady, M. M., Belal, H. E. E., Gadallah, F. M. & Semida, W. M. Selenium application in two methods promotes drought tolerance in Solanum lycopersicum plant by inducing the antioxidant defense system. Sci. Hortic. 266, 109290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109290 (2020).

Liang, Y., Nikolic, M., Bélanger, R., Gong, H. & Song, A. Chapter-5. Silicon-mediated tolerance to salt stress. In: Silicon in Agriculture. (eds Liang, Y., Nikolic, M., Bélanger, R., Gong, H. & Song, A.) Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands. 69–82 doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9978-2_6 (2015).

Desoky, E. S. M. et al. Fennel and ammi seed extracts modulate antioxidant defence system and alleviate salinity stress in cowpea (Vigna unguiculata). Sci. Hortic. 272, 109576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109576 (2020).

Tahir, M. A. et al. Beneficial effects of silicon in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under salinity stress. Pak J. Bot. 38, 1715–1722 (2006).

Merwad, A. R. M. A., Desoky, E. S. M. & Rady, M. M. Response of water deficit-stressed Vigna unguiculata performances to silicon, proline or methionine foliar application. Sci. Hortic. 228, 132–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2017.10.008 (2018).

Zhu, J. K. Plant salt tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 6, 66–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01838-0 (2001).

Chandrashekar, K. & Sandhyarani, S. Salinity induced chemical changes in Crotalaria striata DC plants. Indian J. Plant. Physiol. 1, 44–48 (1996).

Kishor, P. K. et al. Regulation of proline biosynthesis, degradation, uptake and transport in higher plants: its implications in plant growth and abiotic stress tolerance. Curr. Sci. 88, 424–438 (2005).

Alghamdi, S. A. et al. Rebalancing nutrients, reinforcing antioxidant and osmoregulatory capacity, and improving yield quality in drought-stressed Phaseolus vulgaris by foliar application of a bee-honey solution. Plants 12, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12010063 (2022).

Howladar, S. M. A novel Moringa oleifera leaf extract can mitigate the stress effects of salinity and cadmium in bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) plants. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 100, 69–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2013.11.022 (2014).

Rady, M. M., Varma, C., Howladar, S. M. & B. & Common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) seedlings overcome NaCl stress as a result of presoaking in Moringa oleifera leaf extract. Sci. Hortic. 162, 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2013.07.046 (2013).

Hernandez, J., Corpas, F. J., Gomez, M., del Rio, L. A. & Sevilla, F. Salt-induced oxidative stress mediated by activated oxygen species in pea leaf mitochondria. Physiol. Plant. 89, 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-3054.1993.890115.x (1993).

Alscher, R. G., Erturk, N. & Heath, L. S. Role of superoxide dismutases (SODs) in controlling oxidative stress in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 53, 1331–1341. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/53.372.1331 (2002).

Feierabend, J. Catalases in plants: molecular and functional properties and role in stress defence. In Antioxidants and Reactive Oxygen Species in Plants. (ed Smirnoff, N.) Wiley, Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 101–140. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470988565 (2005).

Foyer, C. Free radical processes in plants. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 24, 427–434 (1996).

Foyer, C. H. & Noctor, G. Redox regulation in photosynthetic organisms: signaling, acclimation, and practical implications. Antioxid. Redox Sign. 11, 861–905. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2008.2177 (2009).

Epstein, E. & Bloom, A. J. Mineral nutrition of plants: principles and perspectives. (ed. Epstein). Second Edition, 400 p. (Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, Mass, Oxford University Press, USA, 2005).

Grattan, S. & Grieve, C. Mineral nutrient acquisition and response by plants grown in saline environments. In Handbook of Plant and Crop Stress (2nd edtion) (ed. Pessarakli) pp. 203–229 (Marcel Dekker, New York, USA, 1999) https://doi.org/10.1201/9780824746728.ch9.

Cuin, T. A. Potassium activities in cell compartments of salt-grown barley leaves. J. Exp. Bot. 54, 657–661. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erg072 (2003).

Rios, J. J., Martínez-Ballesta, M. C., Ruiz, J. M., Blasco, B. & Carvajal, M. Silicon-mediated improvement in plant salinity tolerance: the role of aquaporins. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 948–948. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.00948 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by Khalifa Center for Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering-UAEU (Grant number: 31R286), Abu Dhabi Award for Research Excellence-Department of Education and Knowledge (Grant number: 21S105), and UAEU program of Advanced Research (Grant number: 21S169). The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through Large Research Project under grant number RGP2/323/45.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: E-SD, AE, SAQ, and KE-T; methodology and data curation: EZ, E-SA, IM, AAE-H, and BM; software: EZ, E-SA, and IM; validation: DF, E-SD, and AE; formal analysis: EZ, E-SA, IM, and AAE-H; investigation and resources: DF, E-SD, AE, and BM; visualization: EZ, AAE-H, E-SD, and BM; writing original draft preparation: E-SD, AE, SAQ, and KE-T; writing final version, review, and editing: E-SD, UA, LMA, AE, SAQ, and KE-T; funding acquisition: SAQ, and KE-T. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article