Abstract

Blood culture-negative endocarditis (BCNE) is a challenging disease because of the significant impact of delayed diagnosis on patients. In this study, excised heart valves and blood serum samples were collected from 50 BCNE patients in two central hospitals in Tehran, Iran. Sera were tested by IFA for the presence of IgG and IgM antibodies against Bartonella quintana and B. henselae. Genomic DNA extracted from the heart valves was examined for Bartonella-specific ssrA gene in a probe-based method real-time PCR assay. Any positive sample was Sanger sequenced. IgG titer higher than 1024 was observed in only one patient and all 50 patients tested negative for Bartonella IgM. By real-time PCR, the ssrA gene was detected in the valve of one patient which was further confirmed to be B. quintana. Bartonella-like structures were observed in transmission electron microscopy images of that patient. We present for the first time the involvement of Bartonella in BCNE in Iran. Future research on at-risk populations, as well as domestic and wild mammals as potential reservoirs, is recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infective endocarditis (IE) affects the internal structures of the heart1. The heterogeneity in etiology and clinical manifestations along with a 30% mortality rate make IE a life-threatening disease despite its low incidence2. The diagnosis of IE primarily relies on blood cultures, as outlined in the modified Duke criteria (MDC), which are essential for guiding appropriate antimicrobial therapy and surgical interventions. The situation becomes more complicated when the blood culture, a major criterion in the MDC for the diagnosis of IE fails3. In this context, blood culture-negative endocarditis (BCNE) presents a significant challenge for early diagnosis4,5.

BCNE can be caused by infection with fastidious organisms such as nutritionally variant streptococci, fastidious Gram-negative bacilli of the HACEK group (Aggregatibacter aphrophilus, formerly known as Haemophilus aphrophilus and H. paraphrophilus; Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, formerly known as Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans; Cardiobacterium hominis; Eikenella corrodens; Kingella kingae), Brucella spp. (in endemic areas), and fungi. It can also be caused by infections with intracellular bacteria such as the zoonotic agents Coxiella burnetii and Bartonella, as well as Tropheryma whipplei6,7,8. In the genus Bartonella, B. henselae and B. quintana are the most common species associated with BCNE. However, other species like B. washoensis, B. elizabethae, B. alsatica, B. koehlerae, and B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii also play a role in BCNE6,7,9,10. Bartonella quintana infections are more likely to spread in communities affected by war, poverty, and famine11.

The diagnosis of BCNE caused by Bartonella species remains challenging, as the bacteria are notoriously fastidious and difficult to culture in standard laboratory conditions. Serological testing, such as indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA), has proven useful in identifying Bartonella infections, but cross-reactivity with other pathogens and low antibody titers in chronic infections can lead to false negatives. Recent advancements in molecular techniques, such as real-time PCR targeting specific genes like ssrA, have significantly enhanced the accuracy and efficiency of diagnostics for the Bartonella genus12.

Homelessness and alcoholism are also significant contributing factors. The human body louse (Pediculus humanus corporis) is known to transmit B. quintana, while B. henselae is primarily transmitted by cat fleas e.g. Ctenocephalides felis13,14,15. Previous studies reported the prevalence of Bartonella species in cats, dogs, and their ectoparasites in different regions of Iran11,16,17,18. However, there was limited information about the possible role of Bartonella species in BCNEs19. Hence, this study aimed to explore this issue through serology, PCR, and transmission electron microscopy.

Methods

Samples

Between March 2019 and September 2021, fifty excised cardiac valves and their corresponding whole blood samples were collected from patients diagnosed with BCNE who underwent valve replacement surgery at Imam Khomeini Hospital and Shahid Rajaei Heart Center in Tehran. Patients’ demographic, clinical, and laboratory data including hematology and biochemistry results, also echocardiograms were collected. A portion of the valve tissues were fixed in a solution of 2.5% glutaraldehyde buffered at pH 7.2 (at room temperature) for 3 h and postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide (OsO4) in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer for one hour20. The other portion of valve tissue and blood sera were stored in the freezer until further testing.

Serologic testing

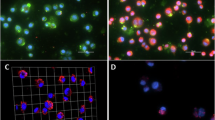

The serum obtained from patients’ blood samples was utilized in an IFA to identify Bartonella antibodies. We used commercial IFA-IgM and IFA-IgG kits (Vircell, Granada, Spain) for the detection of B. henselae and B. quintana antibodies. The presence of apple-green bacilli was observed under an Olympus BX51 fluorescence microscope (Tokyo, Japan). Titers of 64 to 256 suggest a possible Bartonella infection, while titers of 512, combined with clinical symptoms, strongly indicate the disease, as recommended by the kit manufacturer (Vircell, Granada, Spain).

Molecular assays

Genomic DNA of excised valves was extracted using DNP™ kit (SinaClon, Tehran, Iran) and tested using TaqMan probe real-time PCR (qPCR) assay targeting the ssrA gene in CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (BioRad™, Milan, Italy)12.

The ssrA qPCR positive sample/s was/were further tested using additional conventional PCR (cPCR) assays that amplify ssrA (using the same sense and antisense primers used in cPCR assay) and five extra housekeeping genes including ITS (16S–23S rRNA intergenic transcribed spacer), gltA (citrate synthase), nlpD (lipoprotein, outer membrane protein), rpoB (RNA polymerase ß-subunit), and bqtR (B. quintana transcriptional regulator). Selected genes are essential for cellular function and ideal for phylogenetic studies. They also include species-specific regions for differentiation among closely related Bartonella species. These genes have been validated for Bartonella identification and phylogeny, ensuring robust and comparable results12,21,22,23.

DNA amplicons were purified using the NEB Exo-SAP PCR purification kit (New England Biolabs, Inc., Ipswich, MA, U.S.A.) prior Sanger sequencing analysis performed in Eurofins Genomics Center (Vimodrone, Italy), using the same primers used in cPCR assays, and analyzed phylogenetically to enhance the phylogeny’s ability to distinguish between species, using BioNumerics ver 7.1. (Applied Maths NV, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium). For multiple sequence alignment, the sequences of the targeted genes (ssrA, gltA, nlpD, rpoB, bqtR, ITS) obtained in this study were combined with reference sequences of Bartonella strains retrieved from the NCBI GenBank database. We performed standard pairwise alignment and employed single linkage clustering for the phylogenetic analysis22,24.

B. henselae str. Berlin-I, B. henselae Houston-I, and B. henselae Marseille strains that are significant causative agents of BCNE, B. quintana strain Toulouse, B. quintana strain MF1-1, B. quintana strain RM-11, B. taylorii of murine origin, and B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii str. NCTC12905, which is agent of endocarditis in dogs and various complications in humans, and is endemic in different dog populations in Iran16, were used as positive controls in qPCR and cPCR assays.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The heart valve samples that exhibited a positive result for Bartonella detection using the real-time PCR assay were chosen for examination in a transmission electron microscope. To increase the likelihood of observing bacteria by TEM microscopy, vegetative lesion-containing portions of the valve were selected. The fixed tissue samples were then dehydrated by dehydrated for 15–30 min in ascending ethanol concentrations of 30%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100%. Ultrathin sections of valve tissue (50–70 nm) were stained with 2% uranyl acetate and 0.1% lead citrate to visualize the bacteria in a Philips EM 208S microscope (Royal Dutch Philips Electronics Ltd., Eindhoven, The Netherlands)20.

Bacterial culture

Following lysis centrifugation, the whole blood samples of all patients under study were inoculated into Colombia agar base supplemented with 5% defibrinated sheep blood (CBA). The plates were subsequently incubated for a minimum of 21 days at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere25,26.

Results

Fifty patients (41 males, 9 females) underwent replacement of aortic (n = 19), mitral (n = 19) and tricuspid (n = 12) valves. Patients aged 41 years on average (range 3–75 years). None of the patients had a history of drug/alcohol addiction or homelessness. Fever ≥ 38 °C was the most frequently recorded clinical manifestation.

Only one serum exhibited an IgG titer exceeding 1:1024 for both B. henselae and B. quintana. None of the 50 patients had detectable Bartonella IgM antibodies. The seropositive patient was a 55-year-old unemployed man living in Tehran. He had no history of homelessness, alcoholism, valve replacement surgery, or lice infestation.

Blood parameters of that patient were either out of the normal range or critical for clinical decision-making (Table 1).

In pre-surgery transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), the left ventricle was severely enlarged with moderate systolic dysfunction, the right ventricle was moderately enlarged with moderate to severe systolic dysfunction, the left atrium was mildly enlarged, the right atrium was enlarged, and mitral valve leaflets were thickened and tethered. No mitral stenosis was observed, but mild to moderate mitral regurgitation was identified. The aortic valve leaflets were thickened and damaged, resulting in mild aortic stenosis and severe aortic regurgitation. A 27 × 13 mm mobile mass was discovered on the right coronary cusp (RCC), suggesting the presence of vegetation (Fig. 1). The tricuspid valve leaflets were tethered, and although there was no tricuspid stenosis, there was severe tricuspid regurgitation. The pulmonary valve leaflets were normal with moderate pulmonic regurgitation and no pulmonic stenosis. A mobile mass measuring approximately 6 × 3.8 mm was connected to the ventricular side of the pulmonary valve, indicating the presence of vegetation.

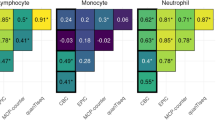

Valve genomic DNA from that patient scored positive by qPCR, and the nucleotide sequence of ssrA gene was suggestive of B. quintana. Amplicons of the expected sizes were obtained also for other targets, as follows. The sample from patient No.10 showed the highest similarity with B. quintana MF1-1 strain for the gltA gene (100%) and the lowest similarity with B. quintana Toulouse strain for the ITS region f (99.4%). Conversely, a low degree of similarity was displayed with the gltA gene sequences of B. henselae strains (89.7%) and B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii (87.6%) (Fig. 2). Furthermore, Bartonella-like organisms organized in the form of invasomes were observed in the TEM micrographs of the patient’s aortic valve (Fig. 3).

Similarity dendrogram was constructed using standard pairwise alignment and single linkage cluster analysis for sequences of ssrA, ITS, gltA, nlpD, rpoB, and bqtR. nlpD gene was absent in Bartonella henselae strain Berlin-I, Bartonella henselae strain Houston-I, Bartonella henselae strain Marseille, and Bartonella vinsonii strain NCTC12905 in the GeneBank database. ssrA gene was absent in Bartonella henselae strain Berlin-I, Bartonella henselae strain Houston-I, Bartonella henselae strain Marseille, and Bartonella taylorii strain M1 in the GeneBank database. ITS locus was present in only Bartonella quintana MF1-1, Bartonella quintana strain RM-11 and Bartonella quintana strain Toulouse in the GeneBank database.

Discussion

We demonstrated that B. quintana also causes BCNE in Iran. A recent systematic review that analyzed cases of B. quintana endocarditis reported between 1993 and 2022, and originated from 40 countries, on all continents except Antarctica, indicated that B. quintana may be more common than previously suggested27. For instance, in the African continent, the presence of B. quintana human infection and lice positivity indicates a hidden burden of illness28. It should be noted that B. quintana infection and bacteremia can be chronic in humans, as is the case with B. henselae infection in cats29, and that in apparently healthy people, chronic bacteremia and low antibody titers may develop30. B. quintana infection has been classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a neglected tropical disease31 and that Institution recommended large studies on the prevalence of B. quintana infection among individuals presenting with fever, heart failure, or symptoms of embolization for a better understanding of the disease epidemiology.

Negative blood cultures are observed in 2.5–31% of cases of infectious endocarditis in developed nations32, whereas they characterize 48–56% of cases in developing countries like Pakistan33, Algeria34, and South Africa35. In a Tunisian study, eleven of thirteen Bartonella seropositive samples of BCNE were confirmed as positive using a nested real-time method that targeted the fur gene36. Another investigation conducted in the United Kingdom identified 12 instances of B. quintana, and one instance of B. henselae among 14 seropositive samples. This was accomplished through semi-nested PCR, which targeted a fragment of the 16S/23S rDNA intergenic spacer region37. In a 12-year survey on bartonellosis in BCNE cases in Spain, 13 cases were caused by B. henselae, and 8 cases were associated with B. quintana38. In the only previous Iranian report on BCNE cases, five out of 59 patients (8.5%) scored real-time PCR positive which were further typed as B. quintana39. Therefore, our results confirm B. quintana as a main source of Bartonella endocarditis in Iran.

The issue of cross-reactivity for Bartonella IFA serology assays with Treponema pallidum, Coxiella burnetii, Chlamydia spp., Rickettsia spp., Orientia tsutsugamushi, Francisella tularensis, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Escherichia coli has been reported40,41. Furthermore, reports of cross-reactivity between B. henselae and B. quintana have been recorded at the species level19,42,43. The same phenomenon was observed for B. henselae and B. quintana in this research. The presence of IgG with the absence of IgM antibodies in the serum sample of positive patients may indicate that the individual was in a chronic infection44. Given the substantial postoperative mortality rates observed in patients who have undergone valvular repair/replacement5 and the invasive nature of Bartonella endocarditis, which often results in valve destruction45,46, as well as the challenges related to cross-reactivity in serological tests, it is advisable to confirm serological results by using the probe-based real-time PCR method, which has excellent sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of BCNEs.

Laboratory abnormalities that are frequently detected in cases of Bartonella endocarditis encompass the following: increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate, anemia, thrombocytopenia, elevated liver enzymes, renal failure indications, leukocytosis, and a positive rheumatoid factor26. Significantly increased levels of BilT and BilD, along with elevated levels of AST, ALT, and ALP hepatic enzymes, indicated the patient’s liver alterations as reported in Table 1. The patient’s laboratory findings, which showed leukocytosis and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, suggested the presence of an inflammatory disease. However, these findings are not exclusive to Bartonella spp.-caused BCNEs. Glomerulonephritis, an additional complication identified in BCNEs caused by Bartonella spp., is further supported by the elevated levels of urea and creatinine47.

Several genes have been used for molecular diagnosis of the Bartonella genus, with the rpoB, the gltA23, and the ssrA12 being the most frequently employed. Two significant benefits are associated with the ssrA gene that can be utilized in molecular testing of human clinical specimens. Predominantly specific to prokaryotes, tmRNA prevents cross-reactivity with human genomic DNA. Furthermore, the sequence diversity of ssrA is adequate to distinguish various human-infective Bartonella species12. A similar methodology and findings have been reported in a case of B. quintana endocarditis in Turkey, where molecular techniques identified the pathogen in the aortic valve48. The ITS (16S/23S rRNA intergenic spacer region) sequencing is a valuable tool for distinguishing specific Bartonella species, such as B. henselae, B. clarridgeiae, and B. bacilliformis, due to the unique ITS sequences associated with each species.49. The ssrA gene also shows sufficient sequence variability for genotyping and differentiating strains within the same species. In a comparative study, the sensitivity of ssrA and rpoB in detecting Bartonella was compared50. The results showed that real-time PCR targeting the ssrA gene was more sensitive than rpoB-PCR in detecting B. clarridgeiae and B. quintana DNA in heart valve specimens. Furthermore, targeting the ssrA gene improved the sensitivity of detecting B. henselae in blood samples50. The reliability of ssrA-based phylogenies is supported by the consistent alignment of phylogenetic relationships obtained from ssrA sequences with those derived from other frequently used markers such as gltA and 16S rRNA12,51. The ssrA-based phylogeny, similar to other single-gene phylogenies, may not provide a comprehensive representation of the entire evolutionary lineage of the genus because of variations in evolutionary rates and gene histories7,52. Additionally, researchers have noted instances of recombination occurring within a single gene (gltA), which can complicate phylogenetic analysis and may not be found in other sequenced genetic loci52,53. The dendrogram in our study, constructed using sequence data, offers higher resolution compared to traditional methods, allowing the detection of subtle genetic variations. For example, the ssrA gene in B. quintana MF1-1 shares about 80% similarity with other B. quintana strains. This can be explained by small variations due to host-specific adaptations and geographical isolation likely contributing to its divergence from the main cluster. Additionally, differences in host specificity (e.g., B. taylorii infecting rodents versus B. quintana infecting humans) and geographical separation likely drove genetic divergence in genes such as gltA, nlpD, and bqtR, explaining the distinct clustering of these strains52,54,55. In our study, the nlpD gene had 99.8% similarity (highest among all) with the gltA gene, and the bqtR gene showed a similarity of 99.7%. It has been shown that rpoB and gltA were the most effective markers for distinguishing between the 17 species and subspecies of the genus Bartonella23. Researchers identified a new Bartonella species (Candidatus B. hemsundetiensis) in Myotis daubentonii bats from Finland by analyzing rpoB and gltA sequences. Thus, multi-locus sequencing provides a valuable balance by potentially offering more reliable assessments of Bartonella diversity compared with single-locus methods22. This feature is highly advantageous in epidemiological studies, as it enables the tracking of transmission patterns and the examination of relationships between hosts.

Echocardiography is essential in diagnosing BCNE. Generally, it confirms the presence of endocarditis, assesses endocardial involvement, and guides treatment decisions56,57. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) however, has a limitation in detecting small vegetations, and hallmark lesions of IE, identifying only 25% and 70% of vegetations less than 5 mm, and between 6 and 10 mm57. In contrast, TTE detects 90–96% of the vegetations on native valves regardless of their size58. The size of vegetation in IE can vary depending on the stage of the disease. They may not be visible or very small in the early phases59. A previous study reported that 93.7% of BCNE cases with vegetation of 17.6 ± 11.3 mm were detected using echocardiography60. Our patient presented two large (> 10 mm) lesions simultaneously. A similar rare case was described previously where a patient with infective endocarditis developed vegetative lesions on the pacemaker electrode61. In the present case, the patient had prior antibiotic use, but because he was referred to different physicians it was not possible to track his medication history. Monitoring vegetation size with TTE can be valuable for assessing the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy and predicting the likelihood of complications. This information can assist in making treatment choices and enhancing patient outcomes62. Larger vegetations, also increase the chances of other complications such as heart failure, renal failure, and neurological issues62,63,64.

Similar to the present patient, there are reported cases of endocarditis due to B. quintana for which no epidemiologic risks (such as alcoholism or homelessness) were identified65,66.

It is known that culturing Bartonella from valve samples is challenging due to the bacterium’s fastidious nature and slow growth, especially when tissue samples are heavily degraded by prior antibiotic use67. Given these challenges and the high sensitivity of probe-based real-time PCR, we opted for molecular detection. The reason behind the failure in the isolation of bacteria in the microbial culture could be that usually when there is endocarditis and vegetations, bacteremia is already gone, as evidenced by IgM seronegativity. This has been observed both in humans and dogs.

Due to the timing of the sampling process coinciding with the outbreak of COVID-19 in Iran and the subsequent strain on the country’s healthcare system in managing the pandemic, we were unable to expand our sample size and obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the prevalence of Bartonella endocarditis in Iran. In addition, because of limited resources, we could not test the samples for other potential causative agents such as Coxiella burnetii and Chlamydia pathogens to the cause of BCNE in the rest of the patients.

Conclusion

We present for the first time the involvement of Bartonella in BCNE in Iran. Future research on at-risk populations, as well as domestic and wild mammals as potential reservoirs, is recommended.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available within the main text of the article.

Abbreviations

- BCNE:

-

Blood culture-negative endocarditis

- IFA:

-

Indirect fluorescent antibody

- IgG:

-

Immunoglobulin G

- IgM:

-

Immunoglobulin M

- MDC:

-

Modified duke criteria

- TEM:

-

Transmission electron microscopy

- LV:

-

Left ventricle

- RV:

-

Right ventricle

- LA:

-

Left atrium

- RA:

-

Right atrium

- MV:

-

Mitral valve

- RCC:

-

Right coronary cusp

- DMSO:

-

Dimethyl sulfoxide

References

Hubers, S.A., DeSimone, D.C., Gersh, B.J., Anavekar, N.S. editors. Infective Endocarditis: A Contemporary Review. Mayo Clinic Proceedings (Elsevier, 2020).

Cahill, T. J. et al. Challenges in infective endocarditis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 69, 325–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.066 (2017).

Li, J. S. et al. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30, 633–638. https://doi.org/10.1086/313753 (2000).

Kong, W. K. et al. Outcomes of culture-negative vs. culture-positive infective endocarditis: the ESC-EORP EURO-ENDO registry. Eur. Heart J. 43, 2770–2780. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac307 (2022).

Salsano, A. et al. Culture-negative infective endocarditis (CNIE): impact on postoperative mortality. Open Med. 15, 571–579. https://doi.org/10.1515/med-2020-0193 (2020).

Maneg, D. et al. Advantages and limitations of direct PCR amplification of bacterial 16S-rDNA from resected heart tissue or swabs followed by direct sequencing for diagnosing infective endocarditis: a retrospective analysis in the routine clinical setting. BioMed Res. Int. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/7923874 (2016).

Maggi, R. G. & Breitschwerdt, E. B. Potential limitations of the 16S–23S rRNA intergenic region for molecular detection of Bartonella species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43, 1171–1176. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.43.3.1171-1176.2005 (2005).

Maurin, M. & Raoult, D. F. Q fever. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12, 518–553. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.12.4.518 (1999).

Dreier, J. et al. Culture-negative infectious endocarditis caused by Bartonella spp.: 2 case reports and a review of the literature. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 61, 476–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.03.008 (2008).

Raoult, D. et al. Outcome and treatment of Bartonella endocarditis. Arch. Internal Med. 163, 226–230. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.163.2.226 (2003).

Oskouizadeh, K., Zahraei-Salehi, T. & Aledavood, S. Detection of Bartonella henselae in domestic cats’ saliva. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2, 80–84 (2010).

Diaz, M. H., Bai, Y., Malania, L., Winchell, J. M. & Kosoy, M. Y. Development of a novel genus-specific real-time PCR assay for detection and differentiation of Bartonella species and genotypes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 1645–1649. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.06621-11 (2012).

Chomel, B. B., Boulouis, H.-J., Maruyama, S. & Breitschwerdt, E. B. Bartonella spp. in pets and effect on human health. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12, 389–394. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1203.050931 (2006).

Chomel, B. B., Kasten, R. W., Sykes, J. E., Boulouis, H. J. & Breitschwerdt, E. B. Clinical impact of persistent Bartonella bacteremia in humans and animals. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 990, 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07376.x (2003).

Chomel, B. & Kasten, R. Bartonellosis, an increasingly recognized zoonosis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 109, 743–750. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04679.x (2010).

Greco, G. et al. High prevalence of Bartonella sp. in dogs from Hamadan, Iran. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 101, 749–752. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.19-0345 (2019).

Shamshiri, Z., Goudarztalejerdi, A., Zolhavarieh, S. M., Kamalpour, M. & Sazmand, A. Molecular Identification of Bartonella species in dogs and arthropod vectors in Hamedan and Kermanshah, Iran. Iran. Vet. J. 19, 104–116. https://doi.org/10.22055/ivj.2022.325115.2436 (2023).

Mazaheri Nezhad Fard, R., Vahedi, S.M., Ashrafi, I., Alipour, F., Sharafi, G., Akbarein, H. & Aldavood, S.J. Molecular identification and phylogenic analysis of Bartonella henselae isolated from Iranian cats based on gltA gene. Vet. Res. Forum. 7, 69–72 (2016).

Vermeulen, M. J., Verbakel, H., Notermans, D. W., Reimerink, J. & Peeters, M. F. Evaluation of sensitivity, specificity and cross-reactivity in Bartonella henselae serology. J. Med. Microbiol. 59, 743–745. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.015248-0 (2010).

Cheville, N. & Stasko, J. Techniques in electron microscopy of animal tissue. Vet. Pathol. 51, 28–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300985813505114 (2014).

Arvand, M., Raoult, D. & Feil, E. J. Multi-locus sequence typing of a geographically and temporally diverse sample of the highly clonal human pathogen Bartonella quintana. PLoS One. 5, e9765. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009765 (2010).

Kosoy, M., McKee, C., Albayrak, L. & Fofanov, Y. Genotyping of Bartonella bacteria and their animal hosts: current status and perspectives. Parasitology. 145, 543–562. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182017001263 (2018).

La Scola, B., Zeaiter, Z., Khamis, A. & Raoult, D. Gene-sequence-based criteria for species definition in bacteriology: the Bartonella paradigm. Trends Microbiol. 11, 318–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0966-842X(03)00143-4 (2003).

Azzag, N. et al. Population structure of Bartonella henselae in Algerian urban stray cats. PLoS One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0043621 (2012).

Dagur, P.K., McCoy Jr, J.P. Collection, storage, and preparation of human blood cells. Curr. Protoc. Cytom. 73, 5.1.–5.1.16. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471142956.cy0501s73 (2015).

Okaro, U., Addisu, A., Casanas, B. & Anderson, B. Bartonella species, an emerging cause of blood-culture-negative endocarditis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 30, 709–746. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00013-17 (2017).

Boodman, C., Gupta, N., Nelson, C. A. & van Griensven, J. Bartonella quintana endocarditis: a systematic review of individual cases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 78, 554–561. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciad706 (2024).

Boodman, C., Fongwen, N., Pecoraro, A.J., Mihret, A., Abayneh, H., Fournier, P.-E., Gupta, N., van Griensven, J., editors. Hidden Burden of Bartonella quintana on the African Continent: Should the Bacterial Infection be Considered a Neglected Tropical Disease? Open Forum Infectious Diseases (Oxford University Press, 2024).

Brouqui, P., Lascola, B., Roux, V. & Raoult, D. Chronic Bartonella quintana bacteremia in homeless patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 340, 184–189. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199901213400303 (1999).

Kostrzewski, J. The epidemiology of trench fever. Bull. Int. Acad. Pol. Sci. Let. Cl. Med. 7, 233–263 (1949).

World Health Organization. Recommendations for the Adoption of Additional Diseases as Neglected Tropical Diseases (WHO, 2017).

Brouqui, P. & Raoult, D. New insight into the diagnosis of fastidious bacterial endocarditis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 47, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00054.x (2006).

Tariq, M., Alam, M., Munir, G., Khan, M. A. & Smego, R. A. Jr. Infective endocarditis: a five-year experience at a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 8, 163–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2004.02.001 (2004).

Benslimani, A., Fenollar, F., Lepidi, H. & Raoult, D. Bacterial zoonoses and infective endocarditis, Algeria. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11, 216–224. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1102.040668 (2005).

Koegelenberg, C., Doubell, A., Orth, H. & Reuter, H. Infective endocarditis in the Western Cape Province of South Africa: A three-year prospective study. QJM. 96, 217–225. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcg028 (2003).

Znazen, A. et al. High prevalence of Bartonella quintana endocarditis in Sfax, Tunisia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 72, 503–507. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2005.72.503 (2005).

Chaloner, G., Harrison, T. & Birtles, R. Bartonella species as a cause of infective endocarditis in the UK. Epidemiol. Infect. 141, 841–846. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268812001185 (2013).

García-Álvarez, L. et al. Bartonella endocarditis in Spain: case reports of 21 cases. Pathogens. 11, 561. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11050561 (2022).

Aghamohammad, S. et al. Fastidious bacterial pathogens in replaced heart valves: the first report of Bartonella quintana and Legionella steeli in blood culture-negative endocarditis from Iran. Multidiscip. Cardiovasc. Ann. https://doi.org/10.5812/mca-139468 (2023).

La Scola, B. & Raoult, D. Serological cross-reactions between Bartonella quintana, Bartonella henselae, and Coxiella burnetii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34, 2270–2274. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.34.9.2270-2274.1996 (1996).

da Goncalves Costa, P. S., Brigatte, M. E. & Greco, D. B. Antibodies to Rickettsia rickettsii, Rickettsia typhi, Coxiella burnetii, Bartonella henselae, Bartonella quintana, and Ehrlichia chaffeensis among healthy population in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 100, 853–859. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02762005000800006 (2005).

Sander, A., Posselt, M., Oberle, K. & Bredt, W. Seroprevalence of antibodies to Bartonella henselae in patients with cat scratch disease and in healthy controls: evaluation and comparison of two commercial serological tests. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 5, 486–490. https://doi.org/10.1128/CDLI.5.4.486-490.1998 (1998).

Magnolato, A. et al. Three cases of Bartonella quintana infection in children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 34, 540–542. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000000666 (2015).

McGill, S. L., Regnery, R. L. & Karem, K. L. Characterization of human immunoglobulin (Ig) isotype and IgG subclass response to Bartonella henselae infection. Infect. Immunity. 66, 5915–5920. https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.66.12.5915-5920.1998 (1998).

Ding, F. et al. Clinical and echocardiographic characteristics of Bartonella infective endocarditis: an 8-year single-centre experience in the United States. Heart Lung Circ. 31, 350–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2021.07.021 (2022).

Lepidi, H., Fournier, P.-E. & Raoult, D. Quantitative analysis of valvular lesions during Bartonella endocarditis. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 114, 880–889. https://doi.org/10.1309/R0KQ-823A-BTC7-MUUJ (2000).

Kitamura, M. et al. Clinicopathological differences between Bartonella and other bacterial endocarditis-related glomerulonephritis—Our experience and a pooled analysis. Front. Nephrol. 3, 1322741. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneph.2023.1322741 (2024).

Özger, H., Gulmez, Z., Celebi, B., Kalkan, I. & Dizbay, M. Bartonella quintana endocarditis of the aortic valve: first case report in Turkey. Gazi Med. J. 31, 206–208 https://doi.org/10.12996/gmj.2020.54 (2020).

Houpikian, P. & Raoult, D. 16S/23S rRNA intergenic spacer regions for phylogenetic analysis, identification, and subtyping of Bartonella species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39, 2768–2778. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.39.8.2768-2778.2001 (2001).

Vesty, A. et al. Evaluation of ssrA-targeted real time PCR for the detection of Bartonella species in human clinical samples and reflex sequencing for species-level identification. Pathology. 54, 449–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pathol.2021.10.014 (2022).

Klangthong, K. et al. The distribution and diversity of Bartonella species in rodents and their ectoparasites across Thailand. PLoS One. 10, e0140856. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140856 (2015).

Buffet, J.-P. et al. Deciphering Bartonella diversity, recombination, and host specificity in a rodent community. PLoS One. 8, e68956. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068956 (2013).

Paziewska, A., Siński, E. & Harris, P. D. Recombination, diversity and allele sharing of infectivity proteins between Bartonella species from rodents. Microbial Ecol. 64, 525–536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-012-0033-y (2012).

McKee, C. D. et al. Diversity and phylogenetic relationships among Bartonella strains from Thai bats. PLoS One. 12, e0181696. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181696 (2017).

Houpikian, P. & Raoult, D. Molecular phylogeny of the genus Bartonella: what is the current knowledge?. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 200, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10684.x (2001).

Rubenson, D. et al. The use of echocardiography in diagnosing culture-negative endocarditis. Circulation. 64, 641–646. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.64.3.641 (1981).

Habib, G., Badano, L., Tribouilloy, C., Vilacosta, I. & Zamorano, J. L. Recommendations for the practice of echocardiography in infective endocarditis. Eur. J. Echocardiogr. 11, 202–219. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejechocard/jeq004 (2010).

Evangelista, A. & Gonzalez-Alujas, M. Echocardiography in infective endocarditis. Heart. 90, 614–617. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2003.029868 (2004).

Tavanaii Sani, A., Mojtabavi, M. & Bolandnazar, R. Effect of vegetation size on the outcome of infective endocarditis in intravenous drug users. Arch. Clin. Infect. Dis. 4: 129–134 (2009).

Munera-Echeverri, A. G. & Saldarriaga-Acevedo, C. Clinical, laboratory, microbiological and echocardiographic characteristics of infective endocarditis in a tertiary care hospital. Acta Med. Colomb. 46, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.7440/res64.2018.03 (2021).

Lejko-Zupanc, T., Kozelj, M., Kranjec, I. & Pikelj, F. Right sided endocarditis: Clinical and echocardiographic characteristics. J. Clin. Basic Cardiol. 2, 81–84 (1999).

Rohmann, S., Erbel, R., Darius, H., Makowski, T. & Meyer, J. Effect of antibiotic treatment on vegetation size and complication rate in infective endocarditis. Clin. Cardiol. 20, 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.4960200210 (1997).

Siddiqui, B. K. et al. Impact of prior antibiotic use in culture-negative endocarditis: Review of 86 cases from southern Pakistan. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 13, 606–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2007.10.009 (2009).

Okonta, K. E. & Adamu, Y. B. What size of vegetation is an indication for surgery in endocarditis?. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thoracic Surg. 15, 1052–1056. https://doi.org/10.1093/icvts/ivs365 (2012).

Fournier, P.-E. et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of Bartonella quintana and Bartonella henselae endocarditis: a study of 48 patients. Medicine. 80, 245–251. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005792-200107000-00003 (2001).

Raoult, D. et al. Diagnosis of 22 new cases of Bartonella endocarditis. Ann. Intern. Med. 125, 646–652. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-125-8-199610150-00004 (1996).

La Scola, B. & Raoult, D. Culture of Bartonella quintana and Bartonella henselae from human samples: A 5-year experience (1993 to 1998). J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 1899–1905. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.37.6.1899-1905.1999 (1999).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Vice-Chancellor of Research and Technology of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran, for advocating this research. We also thank Dr Reza Safiarian and Dr Babak Manafi (Department of Surgery, School of Medicine, Farshchian Cardiovascular Subspecialty Medical Center, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran) for their advice.

Funding

This study was funded by the Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran (Grant number: 9812209686).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A.: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; M.Y.A.: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, resources, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, Funding acquisition; A.S.: Conceptualization, supervision, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; M.H., K.S., G.S., A.N., Y.M., F.B., M.S.: Resources; G.G.: Conceptualization, methodology, resources, validation, original draft, writing—review and editing; B.C.: Conceptualization, validation, original draft, writing—review & editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Review Board of the Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran approved the present study (Ethical approval codes: IR.UMSHA.REC.1398.1021). Ethical Review Board approved informed consent taken from all the participants and all experiments were performed following relevant guidelines and regulations.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies were not used in the writing process.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Azimzadeh, M., Alikhani, M.Y., Sazmand, A. et al. Blood culture-negative endocarditis caused by Bartonella quintana in Iran. Sci Rep 14, 26063 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77757-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77757-0