Abstract

To investigate the seasonal migratory behaviour of spinetail devil rays, Mobula mobular, across the Mediterranean Sea, we used satellite telemetry to track nine individuals between 2016 and 2021. The species is listed as Endangered in the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species and appears to be most vulnerable to fishing impacts when gathering in large assemblages. The only known targeted devil ray fishery harvests significant numbers each winter off Gaza. While broadly distributed during summer across the more productive areas of the western and central portions of the Mediterranean, most tracked rays showed an eastward movement towards eastern Levantine waters during the second half of the year. One individual, tagged off Gaza in March 2016, travelled to Spain before swimming back to the Levantine Sea one year later. Our study corroborates the notion that the species undergoes predictable basin-wide migrations across the Mediterranean Sea, favouring the Levantine waters in late winter and early spring, thanks to the subregion’s milder sea surface temperatures in that time of the year compared to the rest of the Mediterranean. Understanding the species’ seasonal movement pattern in the Mediterranean could support the implementation of robust place-based conservation measures, especially in light of unregulated fishing pressure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mantas and devil rays, collectively known as mobulids, are Myliobatiform Batoids represented by ten species, all classified under the monotypic genus Mobula. These rays have a pelagic lifestyle and are widely distributed across the warm waters of the world1. One species, the spinetail devil ray Mobula mobular (formerly also known as M. japanica2, and as “giant devil ray”3), has a broad circum-tropical distribution and also ranges into warm temperate latitudes4. M. mobular is the only mobulid species which regularly occurs in the Mediterranean Sea3,5.

Due to their large size and epipelagic lifestyle, mobulids are among the most mobile of all Batoids. Long-range movements of the reef manta ray Mobula alfredi were documented through satellite tagging off the east coast of Australia6,7, in one case extending to up to 2,441 km8. High mobility, however, is not a uniform ecological trait in Mobula, not even within the same species. In New Caledonia9 and the Chagos Archipelago10, high variability in horizontal movement patterns amongst reef manta ray individuals was observed, with some remaining within a very confined range (< 10 km) for years, and others engaging in movements exceeding 200 km. A tendency for high site fidelity was also demonstrated by reef manta rays in the Seychelles, with most identified rays exhibiting a restricted movement range11. Surprisingly, oceanic manta rays M. birostris investigated in four sites (two of which in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean, one in Raja Ampat, Indonesia, and one in Sri Lanka) exhibited no long-range migratory movements12, displaying even more restricted movements and fine-scale population structure than reef manta rays.

Spinetail devil rays are known to be highly mobile and able to undertake extensive movements, e.g., off New Zealand13 and in the Eastern Tropical Pacific, where tagged animals were shown to travel hundreds of km in the time span of a few months14. Their tendency to move across extended distances was also highlighted through a preliminary tagging experiment in the Mediterranean Sea15. Knowledge of the ecology of this species in the Mediterranean is scant and fragmentary. M. mobular is broadly distributed across the region and is known to occur in a wide variety of habitats, from oceanic waters far from the coasts to continental shelf areas16. No information is available about the level of connectivity between spinetail devil rays in the Mediterranean and North Atlantic populations: observations of these rays crossing the Strait of Gibraltar are lacking (P. Gauffier, pers. comm.), and no genetic investigations comparing Mediterranean with North Atlantic specimens have been published.

Anecdotal information derived from spinetail devil ray records, assembled on a region-wide scale, provides insights into the geographic extent of the species distribution in the Mediterranean Sea17. Although some of these records are derived from reports of sightings at sea (e.g.18), most of them describe occasional captures in fisheries, e.g., off Tunisia19,20,21, Algeria22,23, the Northern Tyrrhenian Sea24, the Strait of Messina25, Sardinia26, the central and southern Adriatic Sea27, and Türkiye28,29,30,31,32,33.

Systematic observations have provided greater detail of spinetail devil ray ecology in specific Mediterranean locations. These include: (a) results from aerial surveys for cetaceans and sea turtles conducted in the summer of 2010 over the Adriatic Sea, in which 42 spinetail devil ray individuals were recorded in the central and southern Adriatic34; (b) results from a series of aerial surveys for cetaceans conducted between 2009 and 2014 over portions of the western and central Mediterranean, yielding 298 spinetail devil ray sightings16; (c) reports of directed captures of M. mobular in Gaza, Palestinian Territory, going back to 2005, with a peak of 370 rays caught in 201335; and (d) results from the ACCOBAMS Survey Initiative (ASI)—a basin-wide multispecies survey conducted in summer 2018, which yielded an estimate of 25,479 individuals (n = 210; CV = 0.13; 95% CI = 19,490–33,308)36.

Evidence of seasonality in the presence or absence of spinetail devil rays in different parts of the Mediterranean has gradually emerged from some of the observations described above, e.g., with the species frequently observed predominantly during summer in the western Mediterranean16 and the Adriatic Sea18. In contrast, reports from the Levantine Sea are almost entirely limited to winter and early spring months30,31,32,35.

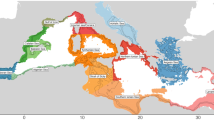

Evidence of differences in the seasonal occurrence of spinetail devil rays in different portions of the Mediterranean also emerges from the MEDLEM database17 (Fig. 1), where the predominance of the rays’ summer presence in the northwestern and central Mediterranean is complementary with the winter occurrence of the species in the Levantine Sea.

Spinetail devil ray Mediterranean occurrences (n = 567) recorded in the MEDLEM database17, subdivided into four longitudinal blocks: South west (waters of Morocco, Algeria, N. Tunisia, n = 24); North west (Spain, France, W Italy, n = 379), Central and North Eastern Mediterranean (Strait of Sicily, Adriatic, Ionian, Aegean, n = 139), Levantine Sea (n = 25). Within blocks, data are subdivided by season, as per cent of the block’s total.

Overall, based on information deriving from a multiplicity of sources, hypotheses have been proposed to argue for the seasonal migratory behaviour of the species across the Mediterranean, recommending further research on the subject16.

Gaining a better understanding of the seasonal distribution and migratory behaviour of spinetail devil rays in the Mediterranean has significant conservation relevance. To implement effective conservation strategies, it is important to fill the existing knowledge gaps concerning their movement ecology and dispersal capabilities through the understanding of the processes that influence their distribution and dynamics. Like all Mobula species, M. mobular is a long-lived k-strategist with a very limited reproductive potential14, and its susceptibility to being impacted by fishery activities in the region that occur discontinuously in space and time is of concern for its survival. In addition to a directed purse-seine fishery off Gaza35, M. mobular is also accidentally caught in a wide range of fishing gears, including purse seines22,30,31, trammel nets18,19, longlines18,37, bottom trawls19,22, pelagic paired trawls27, and fixed tuna traps38; occasionally, the species is also caught by hand harpoon in localised fisheries, such as in the Strait of Messina25. Spinetail devil rays were significantly impacted as by-catch in pelagic driftnets before this gear was banned from the Mediterranean in 200125,39,40. Still, the species is believed to continue to suffer mortality levels in illegal driftnets29 long after this type of fishing was outlawed in the Mediterranean41. Mostly due to threats from fishery activities, M. mobular is globally listed as Endangered in the IUCN’s Red List of threatened species4; for similar reasons, also the Mediterranean subpopulation is listed as Endangered42. At the global level, the species is listed in Appendix I of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS)43 and Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)44. Regionally, M. mobular is listed in Annex II to the Barcelona Convention SPA/BD Protocol45, thereby being the object of GFCM recommendation GFCM/36/2012/3 (amended by GFCM/42/2018/2)46. European Union legislation relevant to the protection of spinetail devil rays includes Regulations 2015/210247, 2016/7248, and 2019/124149. Spinetail devil rays are also protected at the national level in Croatia50, Malta51, Israel52, and Greece53.

This paper aims to help fill knowledge gaps concerning the spatial ecology of Mediterranean spinetail devil rays, including their seasonal migratory patterns, by analysing data obtained through satellite tagging of nine individuals between 2016 and 2021. Considering the uniqueness of these data, the species’ conservation status, and the general lack of knowledge of the migratory habits and habitat use of M. mobular in the region, we hope that the information presented here will contribute to a region-wide implementation of effective management and conservation measures.

Results

A total of nine spinetail devil rays were equipped with satellite transmitters (Table 1).

Horizontal movements

The individual tracks of the nine successfully tagged rays are shown in Fig. 2.

A first ray, an adult male, was tagged off Gaza in March 2016 (PTT 153,622). The ray engaged in a wide journey, moving first to the west along the African coast, crossing the Strait of Sicily in May, travelling all the way to the coast of Spain in June, back eastward north of the Balearic Islands towards the basin west of Corsica and Sardinia in July, where it remained until mid-November; from there, it retraced its earlier westward travel moving again east, reaching the waters off Lebanon and Syria in January before heading again south off Israel.

Of the eight rays tagged in the Strait of Messina, five (PTT 112,706, 202,536, 202,537, 87,640, 87,766) moved out of the Strait soon after being marked in a south-easterly direction; they travelled across the Ionian Sea and around the Italian peninsula, ending up in various locations comprised between the north-eastern Ionian Sea and the central Adriatic Sea, their tags stopping transmitting within a variable number of weeks after the deployment date, between July and November. Two other rays (PTT 87,634 and 112,719), after moving to the south-east out of the Strait of Messina and into the Ionian and Adriatic like the others, turned around and spent considerable time in the central Tyrrhenian before both tags stopped transmitting around mid-November. Finally, a tag attached to the ninth ray (PTT 112,696) lasted enough to reveal its movement until the month of March in the successive year. The animal spent several months swimming back and forth in the Ionian and south Adriatic until January before moving to the eastern Levantine Sea.

All devil rays travelled extensively during their tagging, with reported movements ranging between 14,802 and 1430 km, depending on the duration of the attachment (Table 1). The mean distance covered per day was 30.2 km (SD = 8.2 km, range = 44.9–21.2 km).

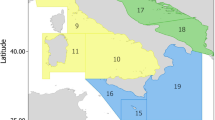

Figure 3 shows the spatial predictions of the probability of encountering spinetail devil rays in the Mediterranean across the different seasons based on selected environmental characteristics—chlorophyll, sea surface temperature, salinity, and zooplankton.

Seasonal spatial predictions of the probability of encountering spinetail devil rays in the Mediterranean, modelled using environmental covariates (see Fig. 4). The predictions highlight key areas where environmental conditions favour the presence of the species, with notable seasonal shifts in distribution, particularly between the Levantine Sea in winter and the central and western Mediterranean during warmer months.

The model points to a very high probability of the presence of rays in winter in the Levantine and Aegean seas based on the environmental variates occurring there in the colder months. A sharp eastward displacement of such probability of occurrence follows in spring, away from the Levantine and Aegean seas in this season, and more uniformly distributed throughout the Mediterranean, with a special emphasis in the central and southern Adriatic Sea. The probability of encountering spinetail devil rays in summer and autumn is similarly distributed across the central and western Mediterranean—with the higher values in autumn likely due to the higher density of available data during this season—while the absence of rays from the Levantine Sea in the warmer months is clearly noticeable.

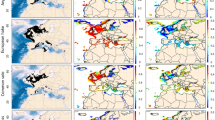

Figure 4 illustrates the probability of spinetail devil ray presence in relation to basic environmental variates such as SST, Chl-a concentration, sea surface salinity, and zooplankton concentration across different seasons. In winter, the probability of devil ray presence increases sharply at temperatures above approximately 17 °C. During spring, there is a peak in presence probability between 17.5 and 20 °C, while in summer, the probability is highest at 24–25 °C. Chl-a concentration also positively affects devil ray presence, with a higher probability of presence in areas with elevated productivity rates, particularly during summer and autumn, possibly indicating a seasonal pattern in foraging behaviour. A higher probability of finding devil rays in less saline waters is also visible in summer, and even more in autumn, indicating a likely preference for upwelling areas. Concerning the probability of finding devil rays in areas of zooplankton concentration, this appears to be highest in summer and autumn, and minimal in the colder season.

Discussion

Our study confirms that spinetail devil rays travel over wide distances within the Mediterranean Sea15, and their movements indicate a seasonal pattern.

The first devil ray tagged in this study (PTT: 153,622) was the only individual to retain the tag for almost a full year, showing a complete migration pattern. The tag remained attached to the ray and functional for 330 days, the longest in our records, likely because the tag was carefully implanted while the ray was restrained in a purse seine before being released. Tagged off Gaza at the beginning of spring in 2016, this individual moved from the eastern Levantine Sea to the western Mediterranean and returned near the location it was tagged at the end of February 2017. The other rays in the sample were tagged in June in the Strait of Messina (Sicily) because no more transmitters could be supplied in the Gaza Strip due to the intervening impossibility of getting the tags through Israeli customs. The pole-implanted tags in the Strait of Messina did not last as long (mean = 130 days, range = 28–271), therefore providing movement information only concerning a portion of their migratory cycle. Nevertheless, evidence from even this partial time window, highlighted by analyses of the movements of the target animals, points to an eastward movement after the end of summer, explaining the presumed concentration of rays in the Levantine Sea during the colder season.

As previously suggested by Notarbartolo di Sciara and colleagues (2015), it is conceivable that spinetail devil rays assemble in the western and central Mediterranean in summer to feed on small schooling fishes and zooplankton, taking advantage of these waters’ greater productivity during summer than in the rest of the Mediterranean54,55. The propensity of spinetail devil rays to engage in feeding behaviour during summer and autumn is revealed by the probability of finding them during these seasons in areas rich in Chl-a and zooplankton concentration, and cooler, less saline waters indicative of upwelling phenomena (Fig. 4). Accordingly, Important Shark and Ray Areas (ISRAs) were identified near the Balearic Islands, in the Corsica Canyons, and in the Ligurian and Tyrrhenian seas based on the observed summer aggregations of spinetail devil rays in these areas56,57. Fishermen from the Strait of Messina informed us that devil rays are rarely seen in Strait waters before summer and that June was the earliest month of the year when they could deploy satellite transmitters on them; an ISRA was identified for M. mobular in the Strait of Messina in view of the area’s importance for the species’ movements46. Spinetail devil rays have been shown to aggregate in productive upwelling systems within the wide expanses of both the Eastern Tropical Pacific58 and the Eastern Tropical Atlantic59, indicating this species’ propensity for extensive migrations, even at the ocean scale, towards places holding a favourable foraging potential.

Conversely, the Mediterranean subpopulation of M. mobular appears to concentrate in the Levantine Sea during winter, in particular around the Gaza ISRA46. The Levantine Sea’s low-productivity waters are the Mediterranean’s warmest in that season60, thus providing energetic advantages to a species which is likely to thermoregulate, as it was shown to occur in closely related species61. Accordingly, a clear increase in the probability of finding devil rays in warmer waters in winter, associated with low probabilities of finding them in productive, zooplankton-rich areas in this season, is evident from Fig. 4.

Several scientific studies emphasise the importance of environmental factors like sea surface temperature (SST), sea surface salinity (SSS), chlorophyll-a, and zooplankton concentrations in the distribution and biology of mobulid rays and other batoids. Fonseca-Ponce et al. (2022) demonstrated that SST highly influences manta rays. Sea surface temperature (SST)62, sea surface chlorophyll-a (SSC-a), and sea surface salinity (SSS) are significant predictors of mobulid ray habitat in coastal areas63. Zooplankton concentrations strongly influence manta ray sightings, particularly species like Calanoid crustaceans and Oithona nana64. Chlorophyll-a levels and lunar cycles affect the occurrence and abundance of planktivorous elasmobranchs, with lower illumination phases correlating with increased mobula ray abundance65. These environmental parameters often interact to create favourable conditions for feeding and reproduction, explaining seasonal or migratory patterns. Based on these observations, we selected SST, SSS, SSC-a, and zooplankton concentration in our model due to their known influence on the distribution and biology of mobulid rays. These variables were extracted from the Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service (CMEMS), ensuring high-resolution, seasonally accurate environmental data. The datasets were accessed for the Mediterranean Sea, providing daily and monthly mean values to capture the seasonal variation required for precise habitat modelling.

The Levantine Sea might not be the only location where spinetail devil rays spend the colder portion of the year: episodes in which numbers of these rays were caught in March along the Tunisian coasts have also been reported (https://tinyurl.com/maeh77cj). However, results from our tagging study indicate that the Levantine Sea is an evident destination for the species during winter.

Quite intriguingly, out of a total of 304 spinetail devil rays landed in Gaza between 2014 and 2016, more than 90% were males, most of which were sexually mature and ready to mate, with sperm oozing from their claspers35. These observations appear contradictory, indicating the possible existence of a sexually segregated population of rays, and yet with the male component seeming ready to actively mate. Devil rays have been rarely documented to sexually segregate (e.g., M. tarapacana in the equatorial mid-Atlantic Ocean66, M. alfredi in Mozambique67). Our current inability to explain why females were so unrepresented in the catches deserves further scientific investigation, as it underscores the possibility that the Levantine spinetail devil ray wintering area might be a breeding ground for the species in the Mediterranean Sea. The Levantine Sea is not the only Mediterranean location where spinetail devil rays are known to engage in reproductive behaviours, which have also been observed in parts of the western basin, such as the Balearic ISRA and the Corsica Canyon ISRA46.

M. mobular from other parts of the world also engage in extensive migratory displacements. Two spinetail devil rays tagged off northern New Zealand migrated 1400 and 1700 km, respectively, northward to near Vanuatu and Fiji13. Long-distance movements were also reported in 13 rays tagged with pop-up archival satellite tags (mean tag duration = 83 days) in the Gulf of California (Mexico); of these, eight were observed moving from inside the Gulf to the Pacific coast of the Baja Peninsula68.

In the absence of any information about the population structure of M. mobular in the Mediterranean, it cannot be assumed that the species is represented in the region by a single panmictic population composed of individuals that irradiate during the summer months into the more productive waters of the central and western portions of the basin to feed and concentrate in the warmer waters of the Levantine Sea during winter. Genetic investigations could reveal whether such a “panmictic hypothesis” is true or if other population nuclei reside during winter in other portions of the southern Mediterranean; we recommend further research in this direction. In the current state of knowledge, it seems that the species is most vulnerable to human impacts (i.e., fishing) when it gathers in large assemblages in the eastern and southern reaches of the Levantine Sea in winter (and possibly in other areas of the southern Mediterranean) and that conservation efforts, including place-based protection measures, should be implemented there: e.g., by establishing a seasonal conservation area along the shores of the concerned countries, where the species should be protected from both directed and accidental fishing activities, such as from the still occurring deployment of illegal pelagic driftnets.

Methods

Tag deployment

Devil rays were tagged using MiniPAT pop-up archival transmitting tag (wildlifecomputers.com) that was secured using a Wilton Anchor and nylon tether. The anchor was placed on the pectoral fin to avoid damaging vital organs. A first ray (Platform Transmitted Terminal (PTT) ID: 153,622) was tagged off Gaza, Palestine, on 31 March 2016, in position 31.7636 N, 34.3289 E (Table 1). Two rays were restrained at sea using a local purse seiner and tagged. However, only one of the two satellite transmitters was functioning; the working tag was implanted onto an adult male, its disc 297 cm wide.

Subsequently, because of the problems encountered in supplying more instruments to be implanted on rays from Gaza for political reasons, a different tagging strategy was adopted in later years (2019–2021) by resorting to the services and experience of swordfish harpoon fishermen in the Strait of Messina (Italy). The satellite transmitters were deployed from traditional local fishing boats, called ‘feluca’, equipped with a 25 m-long gangway and a 25 m-high mast, specifically designed to harpoon swordfish. Spinetail devil rays were first spotted from the mast while they were swimming close to the surface (< 1 m deep), then approached and tagged with a 4 m long pole (see details in15). Fishermen agreed to implant satellite transmitters on devil rays they encountered during their fishing activities. Because of these circumstances, information on the sex of these tagged animals could not be obtained. Based on videos of the implanting episodes provided by the fishermen, it was evident that all the tagged rays were large and, therefore, of adult age.

The tags were programmed to be released after a predefined number of days, at which point they floated to the surface and transmitted their stored data to ARGOS satellites. Position data were then downloaded and processed using Wildlife Computers’ geolocation processing proprietary software (GPE3), setting the swimming speed value to 2 m/s. In two cases, the physical recovery of the tags detached from the animals (one in Syria: PTT 112,696, and one in Tuscany, Italy: PTT 112,619) provided the opportunity to obtain detailed datasets.

All procedures followed internal Tethys Research Institute’s ethical guidelines to ensure the welfare of the devil rays. Short post-tagging monitoring from the boat’s mast indicated no adverse effects on the tagged individuals. No permits to tag the rays were required by the national legislation in either of the nations where tagging was performed.

Analyses

Most Likely Latitude and Longitude, calculated by geolocation processing software, were combined with date and time to reconstruct individual tracks. To calculate distances covered by the individual rays, the tracks were reprojected to Lambert Azimuthal Equal Area (ETRS89-EXT / LAEA Europe ESPG:3035) using QGIS LTR 3.34.4-Prizren. This projection preserves the area at its true relative size while simultaneously minimising distortion from the centre (https://tinyurl.com/hyued4f2), allowing distances to be calculated on the projection plane using simple Euclidean geometry. After reprojecting, a quality check of each track was conducted, and location inaccuracies (temporal and spatial outliers) were manually removed.

This study employed kernel density estimation (KDE) to analyse spatial data representing the XY positions of the nine mobile entities over time69. The KDE was calculated using R70. Initially, each entity’s data in XY coordinates was transformed to facilitate kernel density analysis. The transformation process involved categorising the data into different seasons (indicated by the “seasons” variable in the dataset) and then assigning geographic coordinates (longitude and latitude) to each data point. Following this, the ‘kernelUD’ function from the adehabitatHR package was employed to compute the kernel density estimates for each seasonal subset of data. The kernel density estimation process allowed for a detailed analysis of the mobile entities’ spatial distribution and movement patterns across different seasons. This approach provided valuable insights into the temporal and spatial dynamics of the entities under study, allowing us to calculate the Utilization Distribution (UD) of different devil rays. UD is the bivariate function giving the probability density that an animal is found at a point according to its geographical coordinates. Using this model, one can define the home range as the minimum area in which an animal has some specified probability of being located. The functions used here correspond to the approach described in71. The kernel method has been recommended by many authors for the estimation of the utilisation distribution54,72.

After calculating the kernel density estimates, the spatial predictions were transformed into four distinct raster files, one for each season. This conversion was essential for associating the kernel probability values with various environmental variables at corresponding spatial locations. We compiled these data into a structured data frame to facilitate a comprehensive analysis. In this data frame, the response variable was the probability derived from the kernel density (labelled ‘kernel probability’), and the explanatory variables included the season and the aforementioned environmental factors. To do this, for each spatially explicit kernel density value, a value of each of the environmental variables was extracted, and the corresponding season was associated. This approach allowed us to integrate both spatial probability and environmental variables, providing a multifaceted view of the factors influencing the distribution and behaviour of the mobile entities.

By correlating kernel density probabilities with various environmental conditions, we could investigate how different factors impacted the spatial distribution and movement patterns of the entities across seasons. This methodology enabled us to uncover intricate relationships between the tagged rays and their surrounding environmental conditions, offering insights into ecological dynamics and interactions.

To investigate the relationship between the kernel probability of the devil rays and the environmental characteristics, a Generalized Additive Model (GAM) was implemented73. This approach is particularly adept at highlighting nonlinear relationships between variables. Before fitting the model, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) index examined potential correlations among covariates. This step ensured that multicollinearity did not confound the analysis. Covariates that exhibited significant correlations were removed to maintain the model’s integrity.

The final GAM was constructed to accommodate the response variable’s range, which varies between 0 and 1. Therefore, a beta family was selected for the model, as it is suitable for modelling proportions or probabilities. The model’s formulation included smooth functions of the environmental variables, allowing for flexibility in capturing their relationships with the kernel probability. The final model was expressed as:

kernel probability ~ s(sst, by = factor(season)) + s(chl, by = factor(season)) + s(SSS, by = factor(season)) + s(zoo, by = factor(season))

In this model, ‘sst’ represents the surface temperature, ‘chl’ stands for chlorophyll concentration (as a proxy for phytoplankton), ‘SSS’ is the surface salinity, and ‘zoo’ indicates zooplankton concentration. The use of 's()' denotes a spline function, a key component of GAMs, allowing for the modelling of complex, nonlinear relationships. The inclusion of by = factor(season) enables the model to assess the influence of each season on these relationships.

Following the implementation of the GAM model, thorough residual diagnostics were conducted to ensure the robustness and reliability of the model’s results. This step is crucial in any statistical modelling to validate the assumptions underlying the model and to check for any potential issues that might affect the interpretation of the results74.

The diagnostics examined the model’s residuals to confirm their normal distribution. This is a fundamental assumption in many statistical models, as it underpins the validity of statistical inferences made from the model. A non-normal distribution of residuals can indicate model misspecification, outliers, or other issues that could invalidate the model’s conclusions.

In addition to normality, the analysis also examined the residuals for the absence of any specific trends concerning the independent variables and their spatial distribution. This is important to ensure that the model has adequately accounted for the relationships between the response and explanatory variables and that no unmodeled patterns remain. The absence of trends in residuals for both the independent variables and their spatial distribution suggests that the model has successfully captured the underlying structure of the data without leaving out significant trends or patterns.

Data availability

Data supporting the results reported in the article have been submitted as “Supplementary material”.

References

Stevens, G., Fernando, D., Dando, M. & Notarbartolo di Sciara, G. Guide to the Manta & Devil Rays of the World 144 (Wild Nature Press, 2018).

White, W. T. et al. Phylogeny of the manta and devilrays (Chondrichthyes: Mobulidae), with an updated taxonomic arrangement for the family. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 182(1), 50–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlx018 (2018).

Notarbartolo di Sciara, G., Stevens, G. & Fernando, D. The giant devil ray Mobula mobular (Bonnaterre, 1788) is not giant, but it is the only spinetail devil ray. Mar. Biodivers. Rec. 13, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-020-00187-0 (2020).

Marshall, A. et al. Mobula mobular (amended version of 2020 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2022: e.T110847130A214381504. Accessed on 10 December 2023 (2022).

Notarbartolo di Sciara, G. A revisionary study of the genus Mobula Rafinesque, 1810 (Chondrichthyes, Mobulidae), with the description of a new species. Zool. J. Linnean Soc. 91, 1–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1987.tb01723.x (1987).

Armstrong, A. O. et al. Photographic identification and citizen science combine to reveal long distance movements of individual reef manta rays Mobula alfredi along Australia’s east coast. Mar. Biodivers. Rec. 12, 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-019-0173-6 (2019).

Armstrong, A. J. et al. Satellite tagging and photographic identification reveal connectivity between two UNESCO World Heritage Areas for reef manta rays. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 725. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.00725 (2020).

Jaine, F. R. A. et al. Movements and habitat use of reef manta rays off eastern Australia: Offshore excursions, deep diving and eddy affinity revealed by satellite telemetry. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 510, 73–86. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps10910 (2014).

Lassauce, H., Chateau, O. & Wantiez, L. Spatial ecology of the population of reef manta rays, Mobula alfredi (Krefft, 1868), in New Caledonia using satellite telemetry 1–horizontal behaviour. Fishes 8(6), 328. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes8060328 (2023).

Andrzejaczek, S. et al. Individual variation in residency and regional movements of reef manta rays Mobula alfredi in a large marine protected area. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 639, 137–153. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps13270 (2020).

Peel, L. R. et al. Regional movements of reef manta rays (Mobula alfredi) in Seychelles waters. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 558. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.00558 (2020).

Stewart, J. D. et al. Spatial ecology and conservation of Manta birostris in the Indo-Pacific. Biol. Conserv. 200, 178–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.05.016 (2016).

Francis, M. P. & Jones, E. G. Movement, depth distribution and survival of spinetail devilrays (Mobula japanica) tagged and released from purse-seine catches in New Zealand. Aquatic Conserv. Mar. Freshwater Ecosyst. 27(1), 219–236. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2641 (2016).

Croll, D. A. et al. Vulnerabilities and fisheries impacts: The uncertain future of manta and devil rays. Aquatic Conserv. Mar. Freshwater Ecosyst. 26(3), 562–575. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2591 (2016).

Canese, S. et al. Diving behaviour of giant devil ray in the Mediterranean Sea. Endangered Spec. Res. 14, 171–176. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00349 (2011).

Notarbartolo di Sciara, G. et al. The devil we don’t know: Investigating habitat and abundance of endangered giant devil rays in the North-western Mediterranean Sea. PloS ONE 10(11), e0141189. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141189 (2015).

Mancusi, C. et al. MEDLEM Database, a data collection on large elasmobranchs in the Mediterranean and Black Seas. Mediterranean Mar. Sci. 21(2), 276–288. https://doi.org/10.12681/mms.21148 (2020).

Holcer, D., Lazar, B., Mackelworth, P. & Fortuna, C. M. Rare or just unknown? The occurrence of the giant devil ray (Mobula mobular) in the Adriatic Sea. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 29(1), 134–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/jai.12034 (2012).

Bradai, M. N. & Capapé, C. Captures du diable de mer, Mobula mobular, dans le Golfe de Gabès (Tunisie Méridionale, Méditerranée Centrale). Cybium 25(4), 389–391 (2001).

Capapé, C., Rafrafi-Nouira, S., El Kamel-Moutalibi, O., Boumaiza, M. & Reynaud, C. First Mediterranean records of spinetail devil ray Mobula japanica (Elasmobranchii: Raijformes: Mobulidae). Acta Ichthyologica et Piscatoria. 45(2), 211–215. https://doi.org/10.3750/AIP2015.45.2.13 (2015).

Rafrafi-Nouira, S., El Kamel-Moutalibi, O., Ben Amor, M. M. & Capapé, C. Additional records of spinetail devil ray Mobula japanica (Chondrichthyes: Mobulidae) from the Tunisian coast (Central Mediterranean). Annales. 25(2), 103–108 (2015).

Hemida, F., Mehezem, S. & Capapé, C. Captures of the giant devil ray, Mobula mobular Bonnaterre, 1788 (Chondrichthyes: Mobulidae) off the Algerian coast (southern Mediterranean). Acta Adriatica 43(2), 69–76 (2002).

Hussein, K. B. & Bensahla-Talet, L. New record of giant devil ray (Chondrichthyes: Mobulidae) from Oran Bay (Western Mediterranean Sea). Indonesian Fish. Res. J. 25(1), 55–63 (2019).

Notarbartolo di Sciara, G. & Serena, F. Term embryo of Mobula mobular (Bonnaterre, 1788) from the northern Tyrrhenian Sea. Atti della Società italiana di Scienze naturali e del Museo Civico di Storia naturale di Milano 129(4), 396–400 (1988).

Celona, A. Catture ed avvistamenti di mobula, Mobula mobular (Bonnaterre, 1788) nelle acque dello Stretto di Messina. Annales 14, 11–18 (2004).

Storai, T. et al. Bycatch of large elasmobranchs in the traditional tuna traps (tonnare) of Sardinia from 1990 to 2009. Fish. Res. 109, 74–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2011.01.018 (2011).

Scacco, U., Consalvo, I. & Mostarda, E. First documented catch of the giant devil Mobula mobular (Chondrichthyes: Mobulidae) in the Adriatic SeaJMBA2 - Biodiversity Records. 4 p. (2008).

Akyol, O., Erdem, M., Unal, V. & Ceyhan, T. Investigations on drift-net fishery for swordfish (Xiphias gladius L.) in the Aegean Sea. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 29, 1225–1231 (2005).

Akyol, O., Ceyhan, T. & Erdem, M. Turkish pelagic gillnet fishery for swordfish and incidental catches in the Aegean Sea. J. Black Sea/Mediterranean Environ. 18(2), 188–196 (2012).

Sakalli, A., Yucel, N. & Capapé, C. Confirmed occurrence in the Mediterranean Sea of Mobula japanica (Müller & Henle, 1841) with a first record off the Turkish coasts. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2016, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/jai.13218 (2016).

Basusta, N. & Ozbek, E. O. New record of giant devil ray, Mobula mobular (Bonnaterre, 1788) from the Gulf of Antalya (Eastern Mediterranean Sea). J. Black Sea/Mediterranean Environ. 23(2), 162–169 (2017).

Sakalli, A. Relationship between climate change driven sea surface temperature, Chl-a density and distribution of giant devil ray (Mobula mobular Bonnaterre, 1788) in Eastern Mediterranean: A first schooling by-catch record off Turkish coasts. Yunus Res. Bull. 2017(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.17693/yunusae.v17i26557.280070 (2017).

Gökoğlu, M. & Teker, S. First record of spinetail devil ray, Mobula japanica (Müller & Henle 1841) from the Gulf of Antalya. Acta Aquatica: Jurnal Ilmu Perairan 9(2), 131–132. https://doi.org/10.29103/aa.v9i2 (2022).

Fortuna, C. M. et al. Summer distribution and abundance of the giant devil ray (Mobula mobular) in the Adriatic Sea: Baseline data for an iterative management framework. Scientia Marina 78(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.3989/scimar.03920.30D (2014).

Abudaya, M. et al. Speak of the devil ray (Mobula mobular) fishery in Gaza. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 28, 229–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-017-9491-0 (2017).

ACCOBAMS. Estimates of abundance and distribution of cetaceans, marine mega-fauna and marine litter in the Mediterranean Sea from 2018–2019 surveys. ACCOBAMS - ACCOBAMS Survey Initiative Project, Monaco. 177 p. (2021).

Orsi Relini, L., Garibaldi, F., Palandri, G. & Cima, C. L. comunità mesopelagica e i predatori di superficie. Biologia Marina Mediterranea 1(1), 105–112 (1994).

Boero, F. & Carli, A. Catture di elasmobranchi nella tonnarella di Camogli (Genova) dal 1950 al 1974. Bollettino dei Musei e degli Istituti Biologici dell’Università di Genova 47, 27–34 (1979).

Northridge, S.P. Driftnet fisheries and their impacts on non-target species: A worldwide review. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper, No.320. Rome. 115 p. (1991).

Munoz-Chàpuli, R., Notarbartolo di Sciara, G., Séret, B. & Stehmann, M. The status of the elasmobranch fisheries in Europe. Report of the Northeast Atlantic subgroup of the IUCN shark specialist group. Annex 2 in: R.C. Earll and S.L. Fowler (eds.), Tag and release schemes and shark and ray management plans. Proceedings of the second European Shark and Ray Workshop, 15–16 February 1994, Natural History Museum, London. 23 p. (1994).

Baulch, S., Van Der Werf, W. & Perry, C. Illegal driftnetting in the Mediterranean. Document SC/65b/SM05 presented to the Meeting of the Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission, Bled, Slovenia. 12–24 May 2014. 6 p. (2014).

Notarbartolo di Sciara, G., Serena, F. & Mancusi, C. Mobula mobular. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T110847130A214367431. Accessed on 03 August 2022. (2016).

Convention on the Migratory Species of Wild Animals. Appendix I & II of CMS. https://www.cms.int/en/species/appendix-i-ii-cms (accessed on 19 October 2024).

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. The CITES Appendices. https://cites.org/eng/app/index.php (accessed on 19 October 2024).

Specially Protected Areas Regional Activity Centre. SPA/BD Protocol. https://www.rac-spa.org/protocol (accessed on 19 October 2024).

General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean. Recommendation GFCM/42/2018/2 on fisheries management measures for the conservation of sharks and rays in the GFCM area of application, amending Recommendation GFCM/36/2012/3. https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC201606/ (accessed on 19 October 2019).

Regulation (EU) 2015/2102 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 October 2015 amending Regulation (EU) No 1343/2011 on certain provisions for fishing in the GFCM (General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean) Agreement area. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32015R2102 (accessed on 19 October 2024).

Council Regulation (EU) 2016/72 of 22 January 2016 fixing for 2016 the fishing opportunities for certain fish stocks and groups of fish stocks, applicable in Union waters and, for Union fishing vessels, in certain non-Union waters, and amending Regulation (EU) 2015/104. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2016.022.01.0001.01.ENG (accessed on 19 October 2024).

Regulation (EU) 2019/1241 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on the conservation of fisheries resources and the protection of marine ecosystems through technical measures, amending Council Regulations (EC) No 1967/2006, (EC) No 1224/2009 and Regulations (EU) No 1380/2013, (EU) 2016/1139, (EU) 2018/973, (EU) 2019/472 and (EU) 2019/1022 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and repealing Council Regulations (EC) No 894/97, (EC) No 850/98, (EC) No 2549/2000, (EC) No 254/2002, (EC) No 812/2004 and (EC) No 2187/2005. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/1241/oj (accessed on 19 October 2024).

Regulation on strictly protected species. https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC143051/ (accessed on 19 October 2024).

Flora, fauna and natural habitats protection regulations, 2006. https://legislation.mt/eli/ln/2006/311/eng (accessed on 19 October 2024).

Declaration on National Parks, Nature Reserves, National Sites and Memorial Sites (Protected Natural Assets), Proclamation, 2005 (5765–2005). https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC178773/ (accessed on 19 October 2024).

Presidential decree 67/1981. https://greekbiodiversity-habitats.web.auth.gr/legal/154/ (accessed on 19 October 2024).

Casanova, B. Répartition bathymétrique des euphausiacés dans le bassin occidental de la Méditerranée. Revue des Travaux de l’Institut des Pêches Maritimes 34(2), 205–219 (1970).

Jacques, G. L’oligotrophie du milieu pélagique de Méditerranée occidentale: un paradigme qui s’éstompe?. Bulletin de la Société Zoologique de France 114(3), 17–29 (1989).

Hyde, C. A. et al. Putting sharks on the map: A global standard for improving shark area-based conservation. Front. Mar. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.968853 (2022).

IUCN SSC Shark Specialist Group. Important Shark and Ray Areas Regional Expert Workshop Report: Mediterranean and Black Seas. August 2023. Dubai: IUCN SSC Shark Specialist Group. Available from https://sharkrayareas.org/resources/workshop-reports/ (2023).

Lezama-Ochoa, N. et al. Environmental characteristics associated with the presence of the spinetail devil ray (Mobula mobular) in the eastern tropical Pacific.. PloS ONE 14(8), e0220854. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220854 (2019).

Lezama-Ochoa, N. et al. Spatio-temporal distribution of the spinetail devil ray Mobula mobular in the eastern tropical Atlantic Ocean.. Endangered Spec. Res. 43, 447–460. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01082 (2020).

Malanotte-Rizzoli, P. et al. Physical forcing and physical/biochemical variability of the Mediterranean Sea: A review of unresolved issues and directions for future research. Ocean Sci. 10(3), 281–322. https://doi.org/10.5194/os-10-281-2014 (2014).

Alexander, R. L. Evidence of brain-warming in the mobulid rays, Mobula tarapacana and Manta birostris (Chondrichthyes: Elasmobranchii: Batoidea: Myliobatiformes). Zool. J. Linnean Soc. 118, 151–164 (1996).

Fonseca-Ponce, I. A. et al. Physical and environmental drivers of oceanic manta ray Mobula birostris sightings at an aggregation site in Bahía de Banderas, Mexico. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 694, 133–148. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps14106 (2022).

Putra, M. I. H. et al. Predicting mobulid ray distribution in coastal areas of lesser Sunda seascape: Implication for spatial and fisheries management. Ocean Coastal Manag. 198, 105328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2020.105328 (2020).

Runtuboi, F. et al. Relationship between environmental parameters and manta ray occurrence in Raja Ampat Archipelago, Indonesia. ILMU KELAUTAN: Indonesian J. Mar. Sci. 29(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.14710/ik.ijms.29.1.37-47 (2024).

Saltzman, J. & White, E. R. Determining the role of environmental covariates on planktivorous elasmobranch population trends within an isolated marine protected area. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 722, 107–123. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps14435 (2023).

Alves de Mendonça, S., Luz Macena, B. C., Botelho de Araùjo, C. B., Alvares Bezerra, N. P. & Vieira Hazin, F. H. Dancing with the devil: Courtship behaviour, mating evidences and population structure of the Mobula tarapacana (Myliobatiformes: Mobulidae) in a remote archipelago in the Equatorial Mid-Atlantic Ocean. Neotropical Ichthyology 18(3), e200008. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0224-2020-0008 (2020).

Marshall, A. D. & Bennett, M. B. Reproductive ecology of the reef manta ray Manta alfredi in southern Mozambique. J. Fish Biol. 77, 169–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.2010.02669.x (2010).

Croll, D. A. et al. Movement and habitat use by the spine-tail devil ray in the Eastern Pacific Ocean. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 465, 193–200. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps09900 (2012).

Calenge, C. & Fortmann-Roe, C.F.S. adehabitatHR: Home Range Estimation. R package version 0.4.21, <https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=adehabitatHR> (2023).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. <https://www.R-project.org/> (2023).

Worton, B. J. Using Monte Carlo simulation to evaluate kernel-based home range estimators. J. Wildlife Manag. 59, 794–800 (1995).

Worton, B. J. Kernel methods for estimating the utilization distribution in home-range studies. Ecology 70, 164–168 (1989).

Wood, S. N. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R 2nd edn. (CRC Press, 2017).

Zuur, A. F., Ieno, E. N., Walker, N., Saveliev, A. A. & Smith, G. M. Mixed Effects Models and Extensions in Ecology with R (Springer, 2009).

R Core Team. R Foundation for Statistical Computing (Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing) (2023). Available at: https://www.R-project.org/

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag New York. ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4 (2016). https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org.

Acknowledgements

Funding for the collection of the data described in this paper was provided through a grant from the MAVA Foundation. We are grateful to the captain and the crew of the ‘feluca’ Aquila di Mare for the support and the skills in sighting and tagging the mobulas.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception or design: G.N.S., M.A., S.P.; data acquisition: G.N.S., M.A., J.S., S.P., S.C.; data analysis and interpretation G.N.S., M.A., G.M., S.C., V.P., S.P.; writing G.N.S., G.M., S.P.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

di Sciara, G.N., Abudaya, M., Milisenda, G. et al. Insights into spinetail devil ray spatial ecology in the Mediterranean Sea through satellite telemetry. Sci Rep 15, 2405 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77820-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77820-w