Abstract

Weeding is an important part of agricultural production. With the development of science and technology, automated weeding is regarded as the future development direction, and how to accurately and efficiently detect plants in the field is one of the key points. Corn seedlings and weeds are similar in color, shape and other characteristics, which brings serious challenges to plant detection. In this paper, we propose an improved model based on YOLOv7-tiny, called DC-YOLO. To improve the extraction of key features in the model, we propose Dual Coordinate Attention model (DCA). In addition, we introduce the Content-Aware ReAssembly of FEatures (CARAFE) operator to represent the up-sampling process as a learnable feature reorganization, which enriches the feature information of the sampled images. Finally, we decoupled the detection head to minimize conflicts between features from different tasks. The results show that applying the proposed method to corn and weed datasets, the detection accuracy of the model reaches 95.7% mean Average Precision (mAP@0.5), the computational effort of the model is 13.083 Giga Floating-point Operations (GFLOPs), and the parameter size is 5.223 Millon (M), which is better than the rest of the mainstream light-weight target detection model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Weeds compete with crops for sunlight and nutrients, and also serve as hosts for spreading diseases and pests1, leading to reduced crop yields and severe economic losses. According to statistics, weeds account for 34% of crop losses caused by various biotic stressors2, making weed control an essential task in agricultural production.

Currently, the common methods of weed control are large-scale spraying of herbicides and manual weeding. The former can lead to the abuse of pesticides, causing environmental pollution3, and thus threatening people’s food safety. The latter has higher labor costs and is not suitable for large-scale agricultural operations. With the rapid development of agricultural technology and artificial intelligence, smart weeding has become a viable solution. Compared with traditional weeding methods, it can save a lot of labor and material resources, and control the use of herbicides by accurately identifying the target weeds to achieve the purpose of reducing environmental pollution4. One of the keys to smart weeding is to accurately identify and localize plants in the field. Therefore, it is necessary to propose a plant detection algorithm suitable for the field environment.

Different from other detection tasks, crops are similar to weeds in terms of color, shape, and other characteristics at the seedling stage. Moreover, there are many types of weeds in the farmland, and there are intra-class differences between the same weed at various stages of growth5, which is the difficulty of crop and weed detection. In addition, the field environment is more complex, with changes in light, noise, and other disturbing factors posing challenges to the detection task6.

Early research on field plant detection algorithms focused on the design of feature engineering and the selection and optimization of classifiers. Alchanatis et al.7. used spectral features and robust statistical features to detect weeds. They first segmented the soil and crop using two spectral channel information and then recognized weeds based on texture features of the segmented images with a 15% false detection rate. KC Swain et al.8. used the Automatic Active Shape Matching (AASM) algorithm to identify Solanaceae plants at the two-leaf stage using the shape characteristics of the crop with 90% accuracy for Solanaceae. The above two methods have strong interpretability, but only utilize the shallow features of the plant and have poor robustness. Ahmed et al.9. took chili pepper seedlings and their five companion weeds as their research subjects. In the preprocessing stage, they segmented the plants using a binarization technique based on global thresholding and then used 14 features such as shape and color as the basis for classification, combined with a support vector machine approach, to achieve a recognition accuracy of 97%. Pulicd et al.10. used a gray-level co-occurrence matrix method to get 10 texture measurements and obtained the feature space by principal component analysis, using a parameter-optimized Support Vector Machine (SVM) to complete the classification, with an accuracy of over 90% for weed classification. These methods build recognition models through machine learning and can achieve high recognition accuracy, but require human feature design.

Earlier algorithms used one or a combination of these features as inputs by extracting the color, texture, leaf shape, and other features of a plant in order to distinguish between different types of crops or weeds using a classification method such as SVM. However, these methods require manual completion of feature extraction, which is difficult, and the actual field environment is complex and easily affected by factors such as lighting and shooting angle, so the generalization ability of the algorithm is relatively poor.

In recent years, deep learning technology has received widespread attention, and related research in the direction of computer vision based on deep learning has shown great potential for application11. Deep learning-based methods can automatically extract deep feature information in images by building network models, simplifying the feature extraction process and providing better robustness of the obtained features compared to traditional algorithms. FAWAKHER JI et al.12. combined supervised learning models based on convolutional neural networks with pixel segmentation, to identify crops and weeds in RGB images obtained by sunflower field robots. Jin et al.13. transformed the weed recognition problem into crop recognition. Firstly, the detection of vegetables is completed using the CenterNet model, and then image processing based on color features is performed to achieve weed recognition, which simplifies the complexity of the task. The above two methods fully use color features of crops, weeds, and soil, and use deep learning to improve weed recognition accuracy, but do not explore weed types further. Aanis A et al.14. identified and localized four weeds in corn and soybean using the YOLOv3 network model based on the PyTorch framework, achieving 54.7% mAP. Zhu et al.15. applied the improved attention and Generalized Intersection over Union (GIoU) loss function to YOLOX, with an average detection rate of 92.45% for seedlings and 88.94% for weeds. These two approaches consider both classification and localization problems, but the number of model parameters is large and not easy to deploy on mobile devices.

However, there are still some unresolved issues. In the future, we may need to selectively apply herbicides based on specific weed classes, but some algorithms only categorize plants into two groups: weeds and crops. In addition, the features of weeds and crops are similar to each other, so it is necessary to further extract detailed features to improve the detection accuracy. Considering that mobile embedded devices usually have low computational power, the number of parameters and the amount of computation also need to be considered when designing the model.

Therefore, we propose a field plant detection method DC-YOLO based on the lightweight model YOLOv7-Tiny, and the contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) Original images were obtained by collecting public datasets on the Internet and collecting data in the field. We produced labels in the format required for target detection after data cleaning and expansion.

(2) An improved attention model Dual Coordinate Attention (DCA) is proposed, which effectively enhances the model’s ability to extract key features.

(3) We propose a model DC-YOLO for field plant target detection, which is an optimized algorithm based on YOLOv7-tiny. After experiments, this model outperforms other mainstream lightweight object detection models in our task.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows, with the “Methods” section describing the structure of the model and the rationale for the method. The “Experiments and Discussions” section describes the datasets and experimental environments used, designs several sets of experiments, and discusses the results. The “Conclusion” section summarizes the paper.

Methods

DC-YOLO model framework

In this paper, we propose the DC-YOLO model to address the problems in the field of crop and weed detection. Figure 1 shows the network structure of DC-YOLO. We selected YOLOv7-tiny as the baseline model, which is designed to be lightweight and suitable for deployment on mobile devices while maintaining high detection accuracy. In order to solve the problem of high similarity between weeds and crops, which can be easily detected incorrectly, we propose a new attention model DCA based on the Coordinate Attention16 (CA) module and combine it with the Efficient Layer Aggregation Network (ELAN) module in the backbone network. The new DCA-ELAN has an enriched gradient flow that adaptively adjusts the feature weights according to the feature importance to improve the performance of the model. In the neck of the network, we applied the Content-Aware ReAssembly of FEatures17 (CARAFE) operator, which treats up-sampling as a process of feature reorganization and provides more semantic information to the images obtained after up-sampling by increasing the size of the sensory field of the model and using a learnable sampling method. Finally, we decouple the detectors at the head of the network and use two branches in parallel to handle the classification and localization tasks to solve the problem of feature conflicts between different tasks.

YOLOv7-tiny

YOLOv7 was proposed by Alexey Bochkovskiy et al.18. It performs better than other target detection algorithms of the same period. The size of the model can be controlled by adjusting the coefficients of the depth and width of the model, applied to object detection in different scenarios. YOLOv7-tiny is the lightweight version of this for applications on low-power platforms. The network structure can be divided into three parts: Backbone, Neck and Head.

Backbone network is the main part of the model and is responsible for the feature extraction of the input feature map. It mainly consists of Conv-BN-LeaklyRELU (CBL), ELAN and Maximum Pooling (MP) modules. The CBL module is the basic feature extraction unit in the network, which consists of standard convolution, batch normalization, and LeaklyRelu activation function. MP module is applied to downsample the feature map to reduce the complexity of the model while feature extraction. In the standard version of YOLOv7, a multipath downsampling scheme with convolution and max-pooling is applied, whereas, in the tiny version, only max-pooling is applied to maintain a lightweight structure. The ELAN module consists of two branches, one of which uses only one step of feature extraction, preserving shallow features, and the other branch uses multiple steps of feature extraction, where the results of each step are preserved. After the concat of channel dimensions on the output features, the CBL module is used to interact with the channel information. This results in the preservation of features of different depths in the ELAN module and a rich gradient stream.

Neck part uses the Path Aggregation Network19 (PAN) architecture. As shown in Fig. 2, PAN is composed of a feature pyramid network (FPN)20 and a bottom-up structure. In the process of feature extraction by the backbone network, the shallow feature map contains rich detail information, which is favorable for the detection of small targets, while the deeper feature map contains more semantic information, which is more suitable for detecting large targets. PAN takes as input the feature maps at three different scales generated by the backbone network during the feature extraction process, and the feature information flows and fuses between the three feature layers. Each feature layer contains feature information from other layers at different scales, which allows the model to adapt to the detection of multi-scale targets21.

Head part is used to output predictions. For each feature layer of Neck, YOLOv7-miny uses the CBL module to increase the dimensionality, map the features to a higher dimensional space, and improve the separability of the data. Finally, 1 × 1 convolutional layers are used to complete the integration of features and output the results. The final output tensor shape of the model is B × H × W × C, where B is the BatchSize, which denotes the batch of data processed for each forward propagation, H and W denote the two dimensions of height and width, which represent the size of the feature map. Where C = 3×(N + 5) is the number of channels, that stores the predicted values corresponding to each grid on the feature map, 3 denotes the three preset boxes corresponding to each grid, and N is the number of categories in the dataset, indicating the scores of the targets in that grid belonging to each category, 5 denotes five prediction parameters, the first four of which are used to adjust the preset box, indicating the offset values of the x and y coordinates of the center point and the height and width adjustment parameters. The last parameter indicates the confidence score for the presence of the target in that box.

YOLOv7-tiny is an efficient target detection algorithm with high detection accuracy while maintaining a lightweight model structure. Therefore, we choose YOLOv7-tiny as a baseline and improve it to solve the problems in the field of crop and weed detection.

Dual coordinate attention

Attention mechanism is used to improve the model performance, after feature extraction of the input image, we can obtain the multi-dimensional features. By learning from the data, the attentional model can determine which features are important and assign a higher weight value, while suppressing distracting features like noise that may be present.

Coordinate attention was proposed by HOU et al. in 2021. The method uses two one-dimensional global average poolings along horizontal and vertical coordinate directions to compress the information and embed it into the channel descriptor, followed by feature extraction to obtain the weight matrix and weight the input features, which possesses more accurate positional information compared to other commonly used attention methods. However, this method only uses average pooling to obtain global information in the region, which can ignore local salient features such as the texture information of plants. In field plant detection tasks, weeds, and crops are similar, so it is necessary to retain detailed local features for subsequent classification and localization tasks.

To solve this problem, we design dual coordinate attention (DCA) based on CA attention, specifically, we introduce an additional max pooling branch to capture the salient information in the features and fuse the feature information from the two branches, which helps to further the accuracy and robustness of the model. The model structure is shown in Fig. 3.

For the input feature maps, the original average pooling branch is retained. Additional maximum pooling branches are constructed along the horizontal and vertical coordinate directions to extract local detail information in the feature map, both of which are used as feature descriptors.

Following encoding, the output of the c-th channel in the feature map with height h through the 1D average pooling kernel is shown in Eq. (1). For the 1D maximum pool kernel, the output of the c-th channel in the feature map with height h is shown in Eq. (2).

Similarly, after two pooling branches, the output of the c-th channel in the feature map with width w is denoted as \(Z_{{ca}}^{w}\left( w \right)\) and \(Z_{{cm}}^{W}\left( w \right)\). The obtained four groups of feature tensors \(Z_{{ca}}^{h}\left( h \right)\), \(Z_{{cm}}^{h}\left( h \right)\), \(Z_{{ca}}^{w}\left( w \right)\) and \(Z_{{cm}}^{W}\left( w \right)\) are concatenated into two groups according to their respective branches, and 1 × 1 convolution is used to fuse the information of different spatial directions. The process is shown in Eq. (3) and Eq. (4).

Where δ represents the H-Swish activation function and F represents the convolution operation. For both branches, F is parameter shared, this is to reduce the number of parameters in the module. f1 and f2 denote the feature information from the average pooling branch and the max pooling branch, respectively. After that, the feature information of different directions was segmented, and four groups of feature vectors f1h, f1h, f1w, and f2w were obtained from the two branches. Merging information belonging to the same coordinate axis direction and further feature extraction. We can implement the interaction between the global information and the detailed texture information in the feature map. Finally, the generated attention feature vectors in each of the two directions are applied to the original feature map to enhance the representation of key feature information. The computational process is shown in Eq. (5), Eq. (6), and Eq. (7).

The ELAN in YOLOv7-tiny employs several different branches for feature extraction of the input information so that it can contain rich features from different depth layers. Fusing the information from these branches can effectively improve the utilization of features and learn more complex feature representations. However, the importance of the features of different branches may be different, so we add DCA to the ELAN module. After obtaining the features of multiple paths, we use the attention model to learn the important features among them and assign a higher weight factor. The module is called DCA-ELAN and its structure is shown in Fig. 4.

Up-sampling based on CARAFE operator

In YOLOv7-tiny, up-sampling is used to improve the resolution of the deep feature maps further to enhance the detection of targets at different scales. The model uses the nearest neighbor interpolation method for two up-sampling operations, which has the advantages of small computation and a simple algorithm. However, the method only considers the nearest pixel values and has a small sense field, which makes it difficult to provide more effective information for the sampled image. To solve this problem, we introduce the CARAFE operator. Different from traditional interpolation methods, the CARAFE operator can adaptively accomplish up-sampling based on the current feature information, has a larger sensory field and richer semantic information, and is lighter compared to other learnable up-sampling methods such as transpose convolution. As shown in Fig. 5. The whole operator can be divided into two modules: kernel prediction module and content-aware reassembly module.

For the original feature map x with a given size of C×H×W, and the multiple of up-sampling σ, The size of the upsampled image x’ generated by CARAFE is C × σH × σW. Any point l’ = (i’, j’) in the sampled image has a corresponding point l = (i, j) in the original image, where i = [i’/σ], j = [j’/σ]. Define N(xl, k) as a k×k subregion centered on any point l in the original image x. kencoder denotes the size of the convolutional kernel used to predict the recombination kernel. kup denotes the size of the kernel when feature recombination is subsequently performed.

The recombination kernel wl’ is predicted independently for each position of the sampled image x’ and the process is shown in Eq. (8).

The prediction module ψ for the recombination kernel consists of three parts. First is the channel compression module, which compresses the number of channels C of the original feature map into Cm using 1 × 1 convolution. This reduces the amount of subsequent calculations and parameter counts, keeping the module lightweight. The second part is to generate the recombination kernel, which is encoded using a convolution of size kencoder×kencoder×Cm×Cup, where Cup = σ2k2 up. Finally, the kup×kup reassembly kernel is normalized, and the softmax function is used to make the sum of the reassembly kernel values 1, avoiding changes in the mean value of the original feature map.

The content-aware reassembly module is shown in Eq. (9).

For the feature reassembly, the location l’ in the sampled image x’ can be calculated from the corresponding region N (xl, kup) in the original image centered at l = (i, j) with the recombination kernel wl’, where r = [kup / 2]. Here, we have completed the up-sampling of the image, compared with other up-sampling methods, the image after CARAFE sampling has a larger sensory field and richer semantic information, which helps to improve the detection ability of the model further.

Decoupled detector

Object detection can be decomposed into two subtasks: location and classification. In the YOLOv7-tiny network, the detectors use the same set of convolutions to complete the detection, as shown in Fig. 6a. Specifically, the input feature map is first mapped to a higher dimension feature space using a 1 × 1 convolution. Then the convolution is used to directly predict the category and location information for each grid.

It has been noted in the literature22 that the features of interest are different for classification and location regression tasks. Features in some salient regions may be rich in categorical information, while features around boundaries may be better at bounding box regression. A set of features is used for both tasks, which can lead to conflicts between features, resulting in reduced accuracy. Therefore, in this paper, the decoupled detection head is used to handle these two subtasks separately to improve the detection performance of the model. The structure is shown in Fig. 6b.

The decoupled detection head has two branches, classification and location, with individual branches only focusing on their corresponding features. To reduce the increase in computation due to decoupling operation, we perform channel compression on the input features. Then two 3 × 3 convolutions are used to extract features from their respective branches to alleviate the problem of feature conflicts and improve the detection performance of the model.

Experiments and discussion

Preparation of the dataset

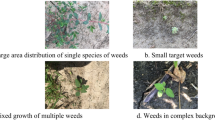

The dataset images used in this paper are primarily from the corn and weeds dataset from the literature23. The dataset was captured by a Canon PowerShot SX600 HS camera vertically orientated to the ground in a natural environment in a field of corn seedlings and contains corn with four common associated weeds such as bluegrass, chenopodium album, cirsium setosum, and sedge. To enrich the sample size, we supplemented it by capturing some corn seedlings in the farmland in Shandong, China, with mobile phones. Finally, the sample dataset is shown in Fig. 7.

Data quality is critical to the validity of the model, and we screened the collected images to obtain high-quality samples from them to construct the dataset. To improve the generalization performance of the model in different scenarios, we extended the data after dividing the dataset into training set, validation set, and test set. As shown in Fig. 8, By rotating, flipping horizontally, and transforming the contrast of the images, we simulated plant images under different shooting angles and lighting conditions. The image quality in a moving scene was simulated by adding noise and motion blur effects. We also increased the number of small target samples by image splicing. Finally, a total of 3859 images were obtained as samples for corn and weed detection, which were divided into train, validation and test sets in the ratio of 6:2:2.

The raw data has only category information and lacks the location information required for object detection. Therefore, it is necessary to produce category and location labels for each target to apply the dataset to the object detection task. We used the visual image annotation tool Labelimg to produce XML file type labels for the dataset, which were eventually collated into VOC format. The labels contain information about the category and location of the target in the image. The category information is represented using different numbers and the location information is represented using the coordinates of the smallest rectangular box containing the target.

Experimental environment and parameter configuration

The operating system used in the experiment is ubuntu20.04, the CPU model is Intel(R) Xeon(R) Platinum 8255 C, equipped with RTX 2080 Ti model GPU, and we use python3.8 as the programming language. The deep learning framework used is pytorch1.11.0.

The training parameters are set as follows: the input image size is uniformly scaled to 640 × 640, the number of training rounds epoch is set to 100, the size of BatchSize is set to 8, and the data is read using a multi-threaded approach, with the number of threads set to 4. For the shapes and sizes of the target samples in the training set, the K-means clustering algorithm is used to obtain 9 different rectangular boxes as the initial preset boxes. In the training phase, to speed up the convergence of the model, the pre-training weights of the model are loaded as initial parameters by key-value matching, and mosaic and mixup data enhancement strategies are turned on. For model optimization, the learning rate adjustment strategy of Adam optimizer and cosine annealing is chosen, where the initial learning rate is set to 1e-3 and the minimum learning rate is 1e-5, which makes periodic changes according to the form of cosine function to help the optimization algorithm to find the minimum value of the loss function. The model is trained on a training set, parameter optimization is performed through a validation set and finally, experimental results are produced on a test set.

Evaluation metrics

In the object detection task, average precision (AP) represents the detection precision of a single category in the dataset and can be calculated based on precision and recall. Mean Average Precision (mAP) as an evaluation of the overall accuracy of the model, represents the average AP value for all categories in the dataset.

Precision denotes the proportion of correct predictions in the set of samples that were predicted to be positive, as shown in Eq. (10).

Recall denotes the proportion of samples in the set of positive samples that are predicted correctly, as shown in Eq. (11).

where P and P denote precision and recall, TP and FP denote the number of positive samples predicted to be in the positive category and the number of negative samples predicted to be positive, and FN denotes the number of positive samples predicted to be in the negative category.

Precision and recall reflect misdetections and omissions in the task and need to be considered together. With P and R as the coordinate axes, the AP is represented by the area of the graph enclosed by the P-R curve and the coordinate axes, which allows for a more comprehensive assessment of the model’s detection effectiveness. The calculation of AP for a single category of targets is shown in Eq. (12).

As shown in Eq. (13), mAP is computed for all classes in the dataset, where N denotes the number of target classes.

Not only classification, the object detection task also needs to focus on the location ability of the model. Therefore, Intersection of Union (IoU) is usually combined to determine when calculating mAP, and only when the threshold is exceeded, the target is considered to be detected. As shown in Eq. (14), IoU represents the intersection and union ratio of the predicted box and the true box, which can reflect the localization ability of the model.

In the experiments of this paper, the model accuracy is evaluated by mAP, which includes two evaluation items: mAP@0.5 indicates the average accuracy of the model when the threshold of the IoU is 0.5, and is also the most commonly used evaluation metric. mAP@0.5:0.95 means that the mAP is computed every 0.05 intervals between the IoUs in the range of 0.5 to 0.95, and the final average value, which can better reflect the detection accuracy of the model under different localization threshold requirements. In addition, FLOPs is used to indicate the number of floating-point operations to measure the complexity of the model, and Params is used to indicate the total number of parameters to evaluate the size of the model, and frames per second (FPS) denotes the number of frames per second that can be processed, which is used to evaluate the inference speed of the model.

Experiments on improved modeling based on attention mechanisms

In this section, we applied the DCA attention model proposed in this paper in the ELAN module of YOLOv7-tiny, experimented on the corn and weed dataset, and compared it with other mainstream attention models (SE, CBAM, CA) in the same application. The results are shown in Table 1. where mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 denotes the accuracy of the model, higher accuracy indicates better detection performance of the model, FLOPs shows the number of floating point operations, where 1GFLOPS indicates 1 billion computations, Params indicates the trainable parameters of the model, and 1 M indicates a million parameters, the lower the number of parameters and computation, the lighter the model. FPS denotes the inference speed of the model, which indicates the number of images per second that the model can reason about.

As can be seen from Table 1, the accuracy of the model of YOLOv7-tiny is improved to different degrees after applying different attention modules, but the detection speed decreases, while the amount of computation and parameters increase slightly. After applying DCA attention, the improved model achieves the best results, reaching 94.8% for mAP@0.5 and 80.6% for mAP@0.5:0.95 in the two accuracy metrics, which is because DCA attention describes the input features in a more comprehensive way and uses the average pooling and the maximum pooling to obtain the global features and the local features, respectively, and the one-dimensional coding along the X-axis and the Y-axis also preserves more accurate positional information, which allows DCA to better weight important features and thus outperform other attention methods. Although the detection speed of the model was reduced, it was still able to meet the task requirements.

Comparative experiments on up-sampling methods

In target detection tasks, up-sampling is used to improve the resolution of deep feature maps and further enhance the detection of targets at different scales. In this section, we design controlled experiments with multiple up-sampling schemes, including bilinear interpolation, transposed convolution, and CARAFE operator, and compare them with the nearest neighbor interpolation method used on the YOLOv7-tiny model, and the results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 shows the results of the upsampling experiments. The original YOLOv7-tiny network uses nearest-neighbor interpolation, which is characterized by simple processing and fast computing speed. The disadvantage is that the algorithm can only use the value of the nearest pixel in the spatial distance, and the sensory field is small, so the detection accuracy is low. The bilinear interpolation method uses four surrounding pixels for interpolation sampling and has a larger receptive field compared to the nearest neighbor interpolation method. Both methods are traditional algorithms with fewer parameters and computations. The up-sampling method of transposed convolution and CARAFE operator implements up-sampling by convolution and the process is learnable. It has a larger sensory field and richer semantic information compared to traditional methods. Compared with transposed convolution, the computational method of the CARAFE operator is more efficient, and the kernel generation is content-aware and can be adaptively adjusted according to the input content, which has certain accuracy advantages. It achieves a detection speed of 86.2 frames per second and outperforms other up-sampling methods by 94.7% at mAP@0.5 and 80.5% at mAP@0.5:0.95.

Comparative experiments of coupled and decoupled detection head

In this section, we compare the effect of coupled and decoupled detection heads on the model and the results are shown in Table 3.

The decoupled detection head uses two branches to accomplish the classification and location regression tasks respectively, and each branch handles the input features separately, which solves the problem of feature conflict and can accomplish more accurate predictions than the coupled detection head. The experimental results show that the detection ability of the model is improved in both accuracy metrics, mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 are 0.9% and 0.2% higher than the prototype model, respectively. In addition, the design of the decoupled detection head reduces the dimensionality of the input features, which effectively reduces the number of parameters and computations of the model.

Ablation experiment

To verify the effectiveness of each module used in the methodology of this paper under individual and combined action, we conducted ablation experiments on corn and weed datasets using YOLOv7-tiny as the baseline model, and the results are shown in Table 4.

As shown by the experimental results, the three improvement strategies play a positive role in improving the detection accuracy of the model when acting individually. After applying the DCA module, mAP@0.5 reaches 94.8%, indicating that the module effectively improves the model’s ability to recognize different types of plants. After using the CARAFE operator, the model has richer semantic information and mAP@0.5 reaches 80.8%. The use of a decoupled detection head not only improves the detection accuracy but also has the lowest parameter and computation. After applying the three improved strategies simultaneously, the model has the highest detection performance, and the two composite metrics of mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 reach 95.7% and 81.7%, which are 1.4% and 1.9% higher than the baseline model, with the number of parameters and computation amount of 13.083G and 5.223 M, respectively. it is lighter compared with the original model. In terms of inference speed, after applying the above module, the inference speed of the model is 62.9 frames per second, which is reduced compared with the original model due to the reduced parallelism of the model, in addition, the inference speed of the model is affected by the type of device, the degree of optimization of the framework for certain operators, and other factors. This inference speed is sufficient for the weed detection task. We named the improved model DC-YOLO.

In order to demonstrate the detection capability of DC-YOLO more intuitively, the prediction results of the proposed model in this paper on the test set are visualized, and the results are shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 9 shows the prediction results of the model. It can be seen that in group A images, DC-YOLO detected a small weed target that was missed by the original model, which reflects the enhanced ability of the model to detect small targets. In group B and C images, the background is more complex, which causes interference with the detection of the target and easily leads to the missed detection of the target. DC-YOLO also solves this problem. The plants in Group D images are characterized by long and thin leaves, with relatively little feature information, which makes detection more difficult. In addition, the background of the plant in the lower right corner is darker, which also increases the detection difficulty, and DC-YOLO successfully detected these samples.

Experiments with mainstream lightweight object detection models

In this subsection, we compare the proposed DC-YOLO with several mainstream lightweight object detection algorithms, such as YOLOv5s, YOLOv7-tiny, YOLOv8s, YOLOXs, and YOLOv9s, and the experimental results are shown in Table 5.

From the experimental results, we can see that the detection performance of YOLOv7-tiny is slightly higher than that of YOLOv5s in our task. on mAP@0.5, YOLOXs is similar to YOLOv7-tiny, while mAP@0.5:0.95 is higher than YOLOv7-tiny, but with a higher computational complexity. YOLOv8s performs mediocrely on the metric mAP@0.5, but outperforms all other models except YOLOv9s on mAP@0.5:0.95, which suggests that the model has high localization accuracy in the case of detected targets. YOLOv9s has high detection accuracy, reaching the highest of 84.1% on mAP@0.5:0.95, which is better than the other methods, but the model’s computational amount is also the highest, along with a lower detection speed. DC-YOLO reaches 95.7% on mAP@0.5 which is comparable to YOLOv9s, and 81.7% on mAP@0.5:0.95 which is lower than YOLOv8s and YOLOv9s, but the parameter and computational complexity are lower than the other models, and the inference speed meets the requirements of the application, and the overall performance is better, which is more suitable to be deployed on mobile embedded devices. In order to qualitatively compare the detection effectiveness of our method with existing state-of-the-art methods on the corn and weed datasets, we visualize the detection results as shown in Fig. 10.

As can be seen in Fig. 10, most of the algorithms are effective in detecting large targets, while the difficulty in detection lies in a number of small targets and targets with more complex image backgrounds. In several groups of images, the number of small targets varies, contains less information, and has a more complex background. For the above difficult-to-detect samples, most algorithms have different degrees of leakage and misdetection.DC-YOLO effectively improves the extraction of key features of the difficult samples by introducing the attention module and CARAFE algorithm. The decoupled detection head further improves the classification and localization accuracy of the model, which reduces the leakage and misdetection rates and also proves the effectiveness of the improved algorithm.

Conclusion

In this paper, we present DC-YOLO, a field plant detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv7-tiny. We designed the DCA attention module to improve the key feature extraction ability of the model and introduced the CARAFE operator to optimize the up-sampling of the model, which increases the sensory field and provides more effective semantic information. By decoupling the detection head design, the problem of model feature conflict is reduced and the classification and localization ability of the model is improved. Experiments on corn seedling and weed datasets show that DC-YOLO achieves 95.7% on mAP@0.5 and 81.7% on mAP@0.5:0.95, and inference at 62.9 frames per second which is better than other mainstream algorithms. However, there are some limitations in this paper: methods such as the attention mechanism and the up-sampling operator lead to an increase in the model inference time, and in order to solve this problem, further research can be carried out in the direction of model lightweight in the future.

Data availability

Publicly available image data supporting this study comes from reference 23, which provides a link. https://github.com/zhangchuanyin/weed-datasets.

References

Ahmad, F. et al. Effect of operational parameters of UAV sprayer on spray deposition pattern in target and off-target zones during outer field weed control application. Comput. Electron. Agric. 172, 105350 (2020).

Oerke, E. C. Crop losses to pests. J. Agric. Sci. 144(1), 31–43 (2006).

Fennimore, S. A., Slaughter, D. C., Siemens, M. C., Leon, R. G. & Saber, M. N. Technology for automation of weed control in specialty crops. Weed Technol. 30(4), 823–837 (2016).

Thomas, L. F., Änäkkälä, M. & Lajunen, A. Weakly supervised perennial weed detection in a barley field. Remote Sens. 15(11), 2877 (2023).

Khan, S. D., Basalamah, S. & Naseer, A. Classification of Plant Diseases in Images Using Dense-Inception Architecture with Attention Modules (Multimedia Tools and Applications, 2024).

Genze, N. et al. Improved weed segmentation in UAV imagery of sorghum fields with a combined deblurring segmentation model. Plant. Methods. 19(1), 87 (2023).

Alchanatis, V., Ridel, L., Hetzroni, A. & Yaroslavsky, L. Weed detection in multi-spectral images of cotton fields. Comput. Electron. Agric. 47(3), 243–260 (2005).

Swain, K. C., Nørremark, M., Jørgensen, R. N., Midtiby, H. S. & Green, O. Weed identification using an automated active shape matching (AASM) technique. Biosyst. Eng. 110(4), 450–457 (2011).

Ahmed, F., Al-Mamun, H. A., Bari, A. H., Hossain, E. & Kwan, P. Classification of crops and weeds from digital images: A support vector machine approach. Crop Prot. 40, 98–104 (2012).

Pulido, C., Solaque, L. & Velasco, N. Weed recognition by SVM texture feature classification in outdoor vegetable crop images. Ingeniería Investig. 37(1), 68–74 (2017).

Ruigrok, T., van Henten, E. J. & Kootstra, G. Improved generalization of a plant-detection model for precision weed control. Comput. Electron. Agric. 204, 107554 (2023).

Fawakherji, M., Youssef, A., Bloisi, D. D., Pretto, A. & Nardi, D. Crop and weeds classification for precision agriculture using context-independent pixel-wise segmentation. Third IEEE Int. Conf. Robotic Comput. (IRC) 146–152 (2019).

Jin, X., Che, J. & Chen, Y. Weed identification using deep learning and image processing in vegetable plantation. IEEE Access. 9, 10940–10950 (2021).

Ahmad, A., Saraswat, D., Aggarwal, V., Etienne, A. & Hancock, B. Performance of deep learning models for classifying and detecting common weeds in corn and soybean production systems. Comput. Electron. Agric. 184, 106081 (2021).

Zhu, H. et al. Research on improved YOLOx weed detection based on lightweight attention module. Crop Prot. 177, 106563 (2024).

Hou, Q., Zhou, D. & Feng, J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 13713–13722 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Carafe: Content-aware reassembly of features. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 3007–3016 (2019).

Wang, C. Y., Bochkovskiy, A. & Liao, H. Y. M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 7464–7475 (2023).

Liu, S., Qi, L., Qin, H., Shi, J. & Jia, J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 8759–8768 (2018).

Lin, T. Y. et al. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2117–2125 (2017).

Khan, S. D., Alarabi, L. & Basalamah, S. Segmentation of farmlands in aerial images by deep learning framework with feature fusion and context aggregation modules. Multimed. Tools Appl. 82, 42353–42372 (2023).

Song, G., Liu, Y. & Wang, X. Revisiting the sibling head in object detector. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 11563–11572 (2020).

Jiang, H. et al. CNN feature based graph convolutional network for weed and crop recognition in smart farming. Comput. Electron. Agric. 174, 105450 (2020).

Kingma, D. P., Ba, J. & Adam A method for stochastic optimization. arxiv preprint arxiv:14126980 (2014).

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Jilin Province of China. (No.YDZJ202401352ZYTS)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.L. proposed a research plan and conducted experimental design, and was the main contributor to manuscript writing. Y.Z. has completed literature research and data preprocessing, and all authors have reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Zhang, Y. DC-YOLO: an improved field plant detection algorithm based on YOLOv7-tiny. Sci Rep 14, 26430 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77865-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77865-x

This article is cited by

-

WeedSwin hierarchical vision transformer with SAM-2 for multi-stage weed detection and classification

Scientific Reports (2025)