Abstract

Industrial green and low-carbon transformation plays a crucial role in China’s efforts to achieve its Carbon peaking and Carbon neutrality objectives. The implementation of environmental regulation policies is a key institutional framework that facilitates this transformation. Therefore, it is of great importance to explore the impact and interplay of these policies on industrial green and low-carbon transformation to foster high-quality economic development. This study categorizes environmental regulation policy instruments into three types: command-type, investment-type, and expense-type. Using industrial panel data from 30 provinces in China spanning the period from 1997 to 2021, both theoretical analysis and empirical testing are conducted to investigate the effects of these different policy instruments on industrial green and low-carbon transformation. The benchmark regression results show that the impact of command-type environmental regulation and investment-type environmental regulation on industrial green and low-carbon transformation shows an inverted U-shaped feature of rising first and then declining. The impact of cost-based environmental regulation on industrial green and low-carbon transformation shows a U-shaped feature of decreasing first and then increasing. The coupling of command-type environmental regulation and investment-type environmental regulation, command-type environmental regulation and expense-type environmental regulation, and the coupling of the three kinds of environmental regulation can promote industrial green and low-carbon transformation. The mechanism test results show that the impact of formal environmental regulation on industrial green and low-carbon transformation has a transmission mode of “formal environmental regulation–green technology innovation path–green and low-carbon transformation.”

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the reform and opening up, China has promoted the rapid expansion of its economic scale by relying on the industry-first development strategy and has successfully achieved a significant leap from the ranks of poor countries to the ranks of upper-middle-income countries1. However, while China’s industrial sector has promoted rapid economic development, the extensive development mode has also led to considerable resource consumption and pollution emissions, and the contradiction between economic development and the ecological environment has become increasingly prominent, which has become a bottleneck restricting China from achieving the “dual carbon” goal and high-quality economic development. To solve increasingly severe environmental problems, the Chinese government clearly noted that “we should accelerate the green transformation of the development model. Green and low-carbon economic and social development is the key to high-quality development.” As the main sector of energy and resource consumption and carbon emissions in China’s economic operation and development pattern, how to achieve green and low-carbon transformation at the present stage has become a hot topic in the field of environmental economics worldwide and an important topic in the process of China’s high-quality economic development.

Theoretically, environmental resources are noncompetitive, nonexclusive and scarce; thus, the definition of environmental resource property rights is relatively vague, and it is difficult to effectively allocate resources by relying on market mechanisms2,1. Therefore, it is necessary to use government means to intervene moderately in economic activities to reduce environmental pollution and resource consumption. Since 1978, the Chinese government has been committed to various types of environmental governance work and has achieved certain results. It has gradually formed a diversified environmental regulation system with Chinese characteristics, which is mainly based on government administrative directives and combines market-oriented methods, providing policy guarantees for environmental quality improvement and green economic growth. However, whether the implementation of China’s environmental policies has effectively reduced pollution emissions and promoted the green transformation of economic development is still unclear. The Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy, Yale University and the Center for International Earth Science Information Network, The 2022 Environmental Performance Index (EPI), which was jointly released by Columbia University, shows that China’s annual EPI score is only 28.4, ranking only 160th among 180 countries, reflecting to a certain extent that China’s overall environmental performance level and intensity of environmental regulation are still weak and that there is a large gap compared with those of other countries4.

China’s existing environmental regulation policies still have certain limitations, and how to build a reasonable environmental regulation system is very important for the green and low-carbon transformation of the economy. At present, the environmental regulation policy tools used in China include command-type environmental regulation, investment-type environmental regulation, and expense-type environmental regulation. What is the effect of environmental regulation policy instruments on industrial green and low-carbon transformation? What is the mechanism through which environmental regulation policy instruments affect industrial green and low-carbon transformation? Moreover, can different environmental regulation policy tools coordinate to promote green and low-carbon industrial transformation? Exploring and answering the above questions can provide not only a scientific and reasonable empirical basis and decision-making reference for the Chinese government to use and adjust various environmental regulation policy tools but also important practical significance for other countries or regions to promote green and low-carbon industrial transformation.

The remaining part of this paper is arranged as follows: The second part is Literature review, the third part is Theoretical analysis and research hypotheses, and the fourth part is Empirical analysis. the fifth part is Data collinearity and stationarity tests, the sixth part is Empirical test, and the seventh part is Replacing the explained variable. The eighth section presents Further research, and the ninth section presents Conclusions.

Literature review

Industrial green and low-carbon transformation entails a shift in the development approach of industries from “high input”, “high energy consumption”, “high carbon emission” and “low benefit” to “high efficiency”, “clean”, “low carbon,” and “circular economy” through technological innovation and upgrading of industrial structures. This transformation aims to achieve a “win-win” scenario by fostering both industrial growth and reduced carbon emissions5. From the perspective of existing research, the literature related to this paper focuses on three main aspects: the connotation and measurement of industrial green transformation or low-carbon transformation, the impact of environmental regulation on industrial green transformation or low-carbon transformation, and the selection of a technological innovation path.

With respect to the definition and measurement of industrial green transformation or low-carbon transformation, scholars adopt a process-oriented perspective that views green transformation as a progression towards “efficient utilization of energy and resources, reduced pollutant emissions, minimized environmental impact, improved labor productivity, and enhanced sustainability.” Various indicators are utilized to reflect this transformation, such as Green TFP6, carbon productivity7, the contribution rate of green TFP to economic growth8, and the ratio of green TFP growth to factor growth rate9. Additionally, attempts are made to construct a multi-dimensional index system for statistical measurement of green or low-carbon development transition. Examples of such systems include the “Green Growth Indicator” by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the Sustainable Development indicator system revised by the United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development (UNCSD), the Comprehensive Evaluation Indicator system for Green Transformation10, and other indicators directly measuring the progress of green or low-carbon transformation11.

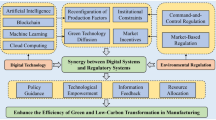

Research on the effects of environmental regulation policy tools on industrial green transformation. As an important means of promoting industrial green transformation, environmental regulation has attracted extensive attention in recent years12. On the basis of Pigou’s “external dieconomy” theory and Coase’s transaction cost model, environmental regulation aims to correct market failure and promote efficient allocation of resources. In the short term, environmental regulation may cause some pressure on industrial production by increasing enterprise costs (such as sewage charges and investment in environmental protection facilities)13. However, in the long run, these regulatory measures can stimulate the technological innovation potential of enterprises, namely, the “Porter hypothesis,” and encourage enterprises to adopt more environmentally friendly and efficient production technologies to reduce costs, increase competitiveness, and achieve green transformation14. Different types of environmental regulation (such as command-type and incentive-type) have their own emphasis on promoting industrial green transformation, and their optimal combination can lead to policy synergy and accelerate the transformation process15. In particular, the close interaction between environmental regulation and clean technology innovation not only reduces environmental pollution but also promotes industrial upgrading, laying a solid foundation for sustainable development16. Therefore, the government should further improve environmental regulation policies and increase support for clean technology innovation to promote the smooth progress of industrial green transformation4.

Research on the realization path of technological innovation originates from the theory of late-comer advantage, which was proposed by Gerchenkron (1962). However, from the perspective of the development of developing countries, the late-comer advantage of technological progress does not reflect the convergence of the technological gap between developing countries and developed countries, and even the technological gap tends to further widen17. Since then, scholars have tried to explain this “practice paradox of late-comer advantage” from the perspective of “technological innovation path selection.” Studies on the realization path of China’s technological innovation can be divided into “factor endowment theory”, which is based on the theory of comparative advantage, and “technological catch-up theory”, which is based on the theory of competitive advantage. On the basis of the theory of factor endowment, some scholars believe that China’s technology choice should match its factor endowment18, and a developing country such as China, which is relatively short in R&D resources and weak in innovation ability, should make full use of the technological gap with developed countries and promote its own industrial technological progress and upgrading through technology import. Since the reform and opening up, China’s rapid economic growth has also largely benefited from the imitation and absorption of advanced technologies at home and abroad19. On the basis of the theory of technological catch-up, some scholars believe that although it is reasonable to achieve technological progress through technology import, its role in achieving technological catch-up and economic growth convergence is questionable.

The existing literature contains valuable discussions that offer essential insights and research directions for this study. However, it also exhibits some limitations. Firstly, prior research has explored the impact of various environmental regulation types on technological innovation from both macro and micro perspectives. Secondly, most studies have focused on the effects of different environmental regulation policy instruments on regional or industrial technological innovation, examining single environmental policies individually. Thirdly, there is a lack of comprehensive theoretical analysis regarding the influence of environmental regulation policy tools on industrial green and low-carbon transformation. The causal relationship between the two has not been sufficiently demonstrated, and the research on how environmental regulation policy tools influence industrial green and low-carbon transformation through the pathway of technological innovation remains scarce.

On this basis, this paper constructs a theoretical analysis framework from the perspective of heterogeneous environmental regulation policy instruments and examines the impact and coupling effect of environmental regulation policy instruments on industrial green and low-carbon transformation using provincial panel data of Chinese industry from 1997 to 2021 as a sample. The possible contributions are reflected in three main aspects. First, the literature focuses on the perspective of environmental regulation on economic green transformation or low-carbon transformation, and there is a lack of systematic and comparable literature on the influencing factors of different environmental regulations on the green and low-carbon transformation of specific industries. On this basis, this paper analyzes the impact of environmental regulation on industrial green and low-carbon transformation from the perspective of direct effects, coupling effects and action mechanisms based on industry, which is conducive to accurately grasping and formulating appropriate environmental regulation policies to promote industrial green and low-carbon transformation. Second, this paper not only studies the heterogeneous effect of a single environmental regulation policy on industrial green and low-carbon transformation but also analyzes the effect of synergistic coupling between environmental regulation policies on industrial green and low-carbon transformation. The research conclusions of this paper provide an empirical basis for clarifying the economic performance and green performance of different environmental regulations. It also provides more targeted suggestions for the formulation and implementation of relevant environmental policies in China. Third, this paper introduces independent R&D and technology imports from the perspective of the technological innovation path and uses the causal mediation model to test the mechanism of the technological innovation path in the process of environmental regulation policy tools affecting industrial green and low-carbon transformation, which further enriches and expands the research in this field.

Theoretical analysis and research hypotheses

Scholars have extensively categorized environmental regulation policy instruments, but there is still no consensus on the criteria for classification. For example, environmental regulation can be classified into formal environmental regulation, where the government takes the lead, and informal environmental regulation, which is driven primarily by public and nongovernmental organizations20. Additionally, environmental regulation can be categorized into three types according to enterprise decision-making: legislative control, law enforcement control, and economic control21. It can also be divided based on the approach to environmental treatment, distinguishing between energy-saving regulation and emission reduction regulation. Another classification is based on the method of environmental input, resulting in two types: expense-type environmental regulation and investment-type environmental regulation22. Finally, environmental regulation can be grouped based on its attributes and forms, resulting in three types: command-type environmental regulation, market-incentive environmental regulation, and voluntary environmental regulation23. Furthermore, environmental regulation can be differentiated into explicit and implicit environmental regulation based on its form24.

To address the purpose and needs of this study, this research combines and integrates the existing classification standards of environmental regulation. It specifically chooses to focus on formal environmental regulation, where the government is the primary entity responsible for implementation. Within this framework, the paper subdivides environmental regulation policy instruments into three categories: command-type environmental regulation, investment-type environmental regulation, and expense-type environmental regulation. The study aims to conduct a theoretical analysis of the impact mechanism and potential coupling effect of these three environmental regulation policy tools on industrial green and low-carbon transformation.

Command-type environmental regulation and industrial green and low-carbon transformation

Command-type environmental regulation refers to the policy in which the state administrative department sets clear environmental goals by promulgation relevant laws, norms and standards and conducts direct management and compulsory supervision of the production and business activities of polluters25. Command-type environmental regulation may affect industrial green and low-carbon transformation through the “innovation compensation effect” and “resource crowding out effect.”

First, command-type environmental regulation may produce an “innovation compensation effect” to promote green technology innovation, thus promoting green and low-carbon industrial transformation26. When the government starts to formulate environmental regulation policies to restrict enterprises’ pollution emission behavior, although it will cause enterprises to incur certain environmental management costs, it will also stimulate enterprises to carry out green technology innovation from the outside. At this time, enterprises choose independent green technology innovation, introduce green technology, purchase green equipment and other ways to obtain corresponding green innovation results through their own innovation knowledge and innovation ability to carry out green improvement on relevant industrial production processes and terminal pollution emission indices27. It also results in more environmental economic output, enterprise competitiveness and social benefits28, which can not only compensate for environmental management costs to some extent but also further strengthen its own innovation motivation, thus forming a virtuous cycle of “compensatory benefits.”

Second, command-type environmental regulation may produce a “resource crowding out effect” to inhibit enterprises’ green technology innovation, which is not conducive to industrial green and low-carbon transformation. When the government gradually improves environmental standards, resulting in an increase in the intensity of command-type environmental regulation, enterprises face serious administrative penalties once they violate the environmental regulations issued by the government, which are characterized by mandatory, high cost and low efficiency29. In the production process, enterprises must strictly abide by the environmental policies formulated by the government and take corresponding measures to reduce environmental pollution emissions, such as purchasing pollution treatment equipment and seeking rent from the government. These measures consume many funds in the process of implementation and crowd out the resources and funds used for technology development when the income source of enterprises does not change30. In the case of resource crowding, on the one hand, enterprises are unable to use a large amount of resources and capital to invest in the development of low-carbon technologies; on the other hand, they also need to bear the R&D risks of low-carbon green technologies, as well as the long cycle of transforming them into practical technologies31.

In summary, the impacts of command-type environmental regulation on enterprises’ green and low-carbon transformation differ in terms of intensity. When the intensity of command-type environmental regulation is low, the “innovation compensation effect” generated by the constraints of environmental laws and regulations is greater than the “resource crowding out effect.” However, when the intensity of command-type environmental regulation exceeds a certain value, the strong constraints, high cost, low efficiency and other characteristics of command-type environmental regulation make the production cost of enterprises too high, which is not conducive to the development of the green R&D activities of enterprises but inhibits their green and low-carbon transformation.

Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the following:

Hypothesis 1

Command-type environmental regulation has an inverted U-shaped effect on industrial green and low-carbon transformation.

Investment-type environmental regulation and industrial green and low-carbon transformation

Investment-type environmental regulation refers to the regulatory action undertaken by the government to establish special funds for the treatment of environmental pollution, aiming to mitigate the negative externalities on the environment caused by corporate production32. This type of regulation can potentially influence the green and low-carbon transformation of industries through the “resource compensation effect” and the “capital crowding-out effect.”

On the one hand, investment-type environmental regulation may foster the “resource compensation effect,” promoting green technological innovation and thereby driving the green and low-carbon transformation of industries. Environmental governance necessitates substantial resource investments by enterprises. The introduction of investment-type environmental regulation policies alleviates a portion of the negative externalities associated with corporate production, reducing enterprises’ expenditures on pollution control. This not only eases resource constraints and financial pressures but also mitigates managers’ concerns about the uncertainty of innovative activities33. Consequently, enterprises can redirect part of their pollution control investments to research and development departments, fostering green technological innovations and enhancing production efficiency34. For example, green technological innovations in product manufacturing processes, assembly procedures, and equipment can promote a green economy, thereby generating the “resource compensation effect”35 and advancing the green and low-carbon transformation of industrial enterprises. Numerous studies have demonstrated the positive role of government investment in pollution control in stimulating enterprises’ green technological innovations.

On the other hand, investment-type environmental regulation may also lead to the capital crowding-out effect, which inhibits green technological innovation and hinders the green and low-carbon transformation of industries. This “crowding-out effect” arises primarily from enterprises’ profit-seeking nature and issues in pollution control investment supervision36. The profit-seeking nature prompts enterprises to disclose favorable environmental information to secure government subsidies, potentially leading to irregularities in information disclosure and the misappropriation of government environmental protection funds37, resulting in resource waste. Additionally, under China’s “tournament” model, it is challenging for local governments to allocate environmental subsidies efficiently and implement idealized supervision38. Consequently, enterprises receiving investments may develop a dependency mindset, neglecting green technology and product development, whereas those without investments lack incentives to engage in green technological innovation39. These two factors contribute to the inefficiency of environmental pollution investments, and the speculative behaviors induced by investment-type environmental regulation can “crowd out” resources intended for environmental management, ultimately impeding enterprises’ green and low-carbon transformation.

Therefore, the impact of investment-type environmental regulation on enterprises’ green and low-carbon transformation varies according to its intensity. Initially, when investment-type environmental regulation is implemented, the resolution of enterprises’ negative externalities encourages them to redirect pollution control investments toward green technology and product development, enhancing production efficiency and promoting green and low-carbon transformation. However, as the intensity of investment-type environmental regulation surpasses a critical threshold, government involvement in environmental governance eliminates most of the enterprises’ negative externalities, potentially leading to complacency and a lack of focus on green technology and product development, thereby hindering the green and low-carbon transformation of industries.

Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the following:

Hypothesis 2

Investment-type environmental regulation has an inverted U-shaped effect on the green and low-carbon transformation of industries.

Expense-type environmental regulation and industrial green and low-carbon transformation

Expense-type environmental regulation refers to the regulatory actions undertaken by the government that directly impact the production and operation processes of enterprises through measures such as levying pollution charges, imposing pollution taxes, or facilitating emissions trading40. This type of regulation can potentially influence industrial green and low-carbon transformation through both “crowding-out effects” and “incentive effects.”

On the one hand, expense-type environmental regulation may hinder green technological innovation and impede industrial green and low-carbon transformation via the “crowding-out effect.” Unlike command-and-control environmental regulation, expense-type regulation directly targets the production processes of enterprises, internalizing the negative externalities of environmental pollution. Firms are thus compelled to allocate funds for environmental governance, such as paying pollution charges, paying environmental taxes, or engaging in emissions trading. These actions directly increase production costs and product prices41. When consumer demand remains unchanged, if the cost of purchasing emissions allowances, paying pollution charges, or environmental taxes is lower than the cost of green technological innovation, firms tend to opt for purchasing emissions allowances, diverting funds that could have been invested in technological innovation toward pollution charges42. This results in the “crowding out” of R&D resources, insufficient R&D supply, and a decrease in green technological innovation patents and outputs, ultimately hindering industrial green and low-carbon transformation.

On the other hand, expense-type environmental regulation can foster green technological innovation and drive industrial green and low-carbon transformation through the “incentive effect.” This incentive effect manifests in both the external and internal dimensions. Externally, stakeholders concerned with environmental issues, including governments, media, and the public, closely monitor ecological conditions, urging enterprises to actively fulfill their environmental responsibilities43. This pressure compels firms to adopt proactive environmental governance strategies, such as standardizing emissions or pursuing green technological innovation, thereby promoting green and low-carbon transformation. Internally, as the intensity of expense-type environmental regulation increases, the cost of pollution control gradually surpasses that of technological innovation44. The substantial expenditure on pollution charges and emissions trading undoubtedly impacts firms’ competitiveness45, prompting managers to weigh the economic losses caused by environmental pollution in their production processes. This drives managers to adopt green innovation strategies, leading to a surge in green invention patents, low-carbon technology patents, and improved environmental and economic outputs. These outcomes further incentivize managers to invest in green and low-carbon technology R&D, creating a virtuous cycle that realizes industrial green and low-carbon transformation.

Hence, the impact of Expense-type environmental regulation on enterprises’ green and low-carbon transformation varies with intensity. Initially, as a short-term measure directly impacting production processes, expense-type regulation forces firms to allocate funds to pollution charges, taxes, or emissions allowances, thereby crowding out R&D funds, reducing innovation, and inhibiting green and low-carbon transformation. However, as the intensity of Expense-type regulation increases and surpasses a tipping point, the profitability of using funds for pollution charges decreases or even becomes negative, compelling firms to proactively adopt green technological innovations to increase product competitiveness and production efficiency, and reduce pollution emissions, thereby promoting industrial green and low-carbon transformation.

Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the following:

Hypothesis 3

Expense-type environmental regulation exerts a “U-shaped” influence on industrial green and low-carbon transformation.

Coupling effect of environmental regulation policy instruments on industrial green and low-carbon transformation

Environmental regulation policy has many fields and complexities, and there are mutual influences among policies in real life. Therefore, when designing and implementing an environmental governance mechanism, the government should not only focus on the environmental governance effect of a single policy but also comprehensively consider whether there is a coupling effect between different environmental regulation policies to have an impact on the green and low-carbon transformation of enterprises46. Environmental regulation policy instruments usually have the following coupling modes:

The first is the coupling of command- and investment-type environmental regulation. Although command-type environmental regulation can force enterprises to transform into green and low-carbon enterprises by setting environmental standards, setting environmental standards that are too high will crowd out enterprises’ research and development funds. At this time, the use of investment-type environmental regulation can help eliminate part of the environmental externalities brought by enterprises’ production, reduce enterprises’ expenditure on pollution control, and effectively alleviate capital shortages. Enterprises are encouraged to carry out green technology innovation47. Like command-type environmental regulation, investment-type environmental regulation also has the problem of the “crowding out effect” of funds in the process of implementation, which leads to poor environmental governance effects, as the government improves the environment while enterprises increase pollution emissions. The use of investment-type environmental regulation combined with command-type environmental regulation to improve the corresponding environmental standards can weaken the possible speculation behavior of enterprises and weaken the capital crowding out effect of investment-type environmental regulation48.

Second, command-type environmental regulation is coupled with cost-type environmental regulation. Command-type environmental regulation sets unified standards for the quantity and method of emissions of enterprises, which is convenient for supervision and management. Compared with command-type environmental regulation, fee-based environmental regulation has greater flexibility and enables enterprise managers to independently choose to carry out green technology innovation or purchase emission rights49. The combination of requirement-based environmental regulation and expense-type environmental regulation not only ensures unified pollution emission standards and reduces rent-seeking behaviors but also enables heterogeneous enterprises to have more space to choose green technology innovation or pollution emission control, which is more conducive to enterprises’ green technology innovation to achieve green and low-carbon transformation50.

The third factor is the coupling of investment-type environmental regulation and cost-type environmental regulation. Both the investment type and the expense type of environmental regulation are market incentive types. Expense-based environmental regulation emphasizes the regulation of enterprises’ pollution emissions, whereas investment-type environmental regulation mainly addresses the negative environmental externalities generated by enterprises51. When enterprises are faced with both Expense-type environmental regulation and investment-type environmental regulation, the intensity of both may affect the production decisions of enterprise managers: if the intensity of Expense-type environmental regulation is greater than that of investment-type environmental regulation, this indicates that the government’s environmental governance has not completely eliminated the negative environmental externalities. Similarly, if the intensity of expense-type environmental regulation is less than that of investment-type environmental regulation, this indicates that the effect of the government’s environmental governance has reached the specified level.

Fourth, the integrated use of command-type environmental regulation, investment-type environmental regulation and expense-type environmental regulation. Command-type environmental regulation aims to set consistent environmental standards for society, whereas investment-type and expense-type environmental regulation are environmental regulation policy tools that serve the market, influencing enterprises’ emission behavior through market signals and internalizing environmental externalities by economic means25. Owing to the differences between regions, the implementation of command-type environmental regulation may cause the problems of “rent-seeking” and “pollution refuge,” which cannot maintain balanced development between regions. Through market behavior, investment-type environmental regulation and expense-based environmental regulation urge enterprises to carry out independent pollution control at the minimum economic cost, which will alleviate the behavioral motivation of enterprises to shift production bases due to command-type mitigation regulation. However, owing to the scarcity and publicity of environmental resources and the negative externality of environmental pollution, relying only on market mechanisms to address the resource consumption and environmental pollution caused by industrial production is unrealistic, and it is also necessary to use government means to moderately intervene in industrial economic activities (Dong et al., 2021). On the basis of the above theoretical analysis, the following research hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 4

Coupling with formal environmental regulation may promote the green and low-carbon transformation of industry.

Empirical analysis

Model setting

Benchmark regression model

Building on the earlier theoretical analysis, to investigate the connection between environmental regulation policy instruments and industrial green and low-carbon transformation, we adopt the system Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) model for parameter estimation. Following the approach used by Wenbo et al.52, we include the lagged term of industrial green and low-carbon transformation in the model as an instrumental variable for endogeneity testing. This approach helps mitigate the endogeneity issue arising from bidirectional causality. The specific model is presented below:

where LGLit represents industrial green and low-carbon transformation, erit represents environmental regulation policy instruments (command-type environmental regulation, investment-type environmental regulation and expense-type environmental regulation), (lnerit)2 quadratic term of environmental regulation policy instruments, and control represents control variable; i is the province, t is the time; α0 is the constant term, vi represents the unobservable provincial individual effect, µt represents the time effect, and εit is the random disturbance term. Due to the lag of the impact of environmental policy instruments on industrial green and low-carbon transformation, LGLit starts from the leading first-period item of Y.

Coupling effect model

Individually, command-type environmental regulation, investment-type environmental regulation, and expense-type environmental regulation policy tools each have both positive and negative impact mechanisms on industrial green and low-carbon transformation. To investigate the combined effect of these environmental regulation policy tools on industrial green and low-carbon transformation, we introduce the coupling coordination degree (lndocit) between command-type environmental regulation, investment-type environmental regulation, and expense-type environmental regulation53. The specific model is formulated as follows:

Among these factors, α5 quantifies the coupling effect of the combined use of command-type environmental regulation, investment-type environmental regulation, and expense-type environmental regulation on China’s industrial green and low-carbon transformation. Additionally, taking into account the possibility that these three types of environmental regulation may jointly promote industrial green and low-carbon transformation, we introduce the coupling coordination degree (lncciit) to verify their combined impact54. The specific model is presented as follows:

Variable selection and data description

Explained variable

For the measurement of Industrial Green and Low-carbon Transformation (LGLit), we adopt the green and low-carbon total factor productivity calculated using the super efficiency EBM model and GML model, which consider the unexpected output and are based on the common frontier. The index for industrial green and low-carbon transformation is then accumulated. When quantifying industrial green and low-carbon TFP, the following input variables are utilized:

Capital input: Industrial capital stock over the years measured using the “perpetual inventory method”. The calculation of the capital stock in the base period refers to the treatment method of Chen et al.41, and the capital depreciation rate is based on the differentiated capital depreciation rate by year of Yu55. The actual fixed asset investment price index of each province is deflated with 1997 as the base period.

Labor input: The measurement is based on the average number of all industrial employees in each province. For provinces with missing data in 2012, we use the linear interpolation method to fill the gaps.

Energy input: We use the total energy consumption of industrial enterprises in each province, which is converted into ten thousand tons of standard coal using the standard coal conversion factor.

The selected output variables are as follows:

Desired output: The gross industrial output value data from 1997 to 2012 can be directly obtained from the “China Industrial Statistical Yearbook”. Since 2013, it has not been included in the statistical yearbook. Therefore, according to the formula “gross industrial output value = industrial sales output value - previous year’s inventory + current year’s inventory”, the data of gross industrial output value from 2013 to 2021 are supplemented.

Undesirable output: Carbon dioxide emissions (CO2) are used as the undesirable output. In the literature, two main methods are used to calculate the data of CO2 emissions: one is to multiply the total coal, oil, and natural gas consumption of each region in the energy balance table by the carbon emission coefficient of the corresponding energy to obtain the CO2 emissions of each region. This method is relatively rough because there are various specific types of subdivided energy in coal and oil products, and their carbon emission coefficients are not the same. Another method calculates CO2 emissions according to the terminal consumption of 28 primary energy sources in the energy balance table of different regions. In this way, the error of the calculated results is smaller, which is used by more scholars to calculate CO2.

However, different scholars have different methods for selecting specific energy segments to measure CO2. This paper uses the carbon dioxide emissions (CO2) of each province in China from 1997 to 2021 calculated and published by the China Carbon Accounting Database (CEADs) to measure undesirable outputs56. The reasons are as follows: first, the China Carbon Accounting Database (CEADs) is a carbon emission data platform jointly funded by the Ministry of Environmental Protection and the National Bureau of Statistics of China. Second, the CO2 calculation results of the China Carbon Accounting Database (CEADs) have an error within 3% with the data officially published by relevant national departments, and the accuracy is verified (the carbon emission data officially disclosed by relevant national departments are few and published in very few years). Third, the CO2 data calculated by the China Carbon Accounting Database (CEADs) have been used by researchers, and many high-quality academic journal papers and doctoral dissertations have been published, which means that the CEADs have been recognized by academia to some extent57.

Core explanatory variables

-

(1)

Command-type environmental regulation (cer): This paper refers to the measurement methods of Liu et al.58 and Chen et al.59 to measure the command-type environmental regulation by the number of environmental administrative penalty cases each year.

-

(2)

Expense-type environmental regulation (cber). Following the research of Li et al.60 and Ye et al.34, we use the ratio of sewage fee revenue to GDP for measuring the extent of expense-type environmental regulation. For the period from 2002 to 2006, the indicator represents the income from sewage charges; from 2007 to 2017 and beyond, it denotes the amount of discharged wastewater; and for the years 2018–2021, it refers to the environmental protection tax. The original data is sourced from the China Tax Yearbook.

-

(3)

Investment-type environmental regulation (ier). Drawing from the studies conducted by Wu et al.61 and Gong et al.62, we utilize the ratio of investment in environmental pollution control to GDP as a measure of investment-type environmental regulation. The data is obtained from the China Environmental Statistical Yearbook.

-

(4)

Coupling and coordination degree of environmental regulation policy instruments (doc). To assess the interplay between different environmental regulation policy tools, we calculate the collaborative coupling degree of these tools. This approach is inspired by the capacity coupling coefficient model in physics, and we refer to the research of Cao63 and Naikoo et al.64for this calculation. The model for assessing the coupling degree of the interaction between the two systems is as follows.

The coupling degree model of the interaction of the three systems is as follows:

In Eqs. (4) and (5), ERi represents the level of intensity for each environmental regulation policy instrument, and O denotes the coupling degree, which indicates the extent of interaction between different environmental regulation policy instruments and ranges from 0 to 1. To achieve a more precise assessment of the collaborative coupling among these policy instruments65, we develop a collaborative coupling model as follows:

In Eq. (6), the variable C represents the degree of coupling and synergy among environmental regulation policy tools, and S is the comprehensive evaluation index that assesses the synergistic effect of combining these tools. The coefficients α, β, and γ, which sum up to 1, determine the contribution of the synergistic and coupling effects among the environmental regulation policy tools, respectively. As the current rankings of the importance of environmental regulation policies by governments at various levels are not available, we assume equal importance for each policy when calculating the synergy degree of different policy combinations.

By employing the aforementioned methods, we obtain the coupling synergy degree (ci) of command-type environmental regulation and investment-type environmental regulation, the coupling synergy degree (cc) of command-type environmental regulation and expense-type environmental regulation, the coupling synergy degree (bi) of investment-type environmental regulation and expense-type environmental regulation, and the coupling synergy degree (cci) of the three environmental regulation tools.

Control variables

R&D input (ede): The industrial R&D expenditure (both internal and external) in each province contributes to green technology innovation, leading to improvements in process technology at both the front and end stages. This optimization of resource allocation and substitution of traditional production factors enhances the output of green products and drives the green and low-carbon transformation of industries. R&D expenditure is first converted into R&D capital stock using the perpetual inventory method, and then the ratio of R&D capital stock to total industrial output value is used to measure R&D investment66.

Foreign direct investment (fdi): Foreign direct investment facilitates the introduction of green technology and advanced management practices through technology diffusion or spillover effects. This enables local enterprises to acquire cutting-edge green technology and adopt cleaner production methods to reduce environmental pollution67.

Human capital (hr): Human capital plays a crucial role in facilitating independent R&D by enterprises, influencing the development and utilization of green technologies68. Additionally, it determines the technology absorption capacity of local industrial enterprises. Therefore, human capital is an essential and influential factor in achieving green and low-carbon transformation.

Urbanization level (ul): As urbanization progresses, the use of supporting industries, transportation vehicles, and energy significantly affects the development of industrial sectors and carbon emissions. The proportion of the urban population in the total regional population is used as an indicator to reflect the level of urbanization69.

Industrial structure (is): The output value of the tertiary industry reflects the local economic development, and the energy consumption in the tertiary industry is relatively low. Hence, this study selects the proportion of the tertiary industry’s output value in the local GDP of each province as an indicator to gauge the level of industrial structure70.

Data source and descriptive statistics

The primary data used in this study were collected from various official sources, including the China Industrial Statistical Yearbook, China Environment Yearbook, China Science and Technology Statistical Yearbook, China Energy Statistical Yearbook, China Statistical Yearbook, and relevant websites of the National Bureau of Statistics. To ensure data availability, the provincial panel data for China’s industry from 1997 to 2021 were selected for analysis. (The Tibet Autonomous Region was excluded due to insufficient data, and Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan were not included in this study due to data accessibility challenges). Descriptive statistics of the relevant variables can be found in Table 1.

Data collinearity and stationarity tests

Multicollinearity test

High correlation among explanatory variables can lead to undesirable consequences, such as invalid estimation results, coefficients with unreasonable economic significance, and insignificance in the tests of variable significance. However, the benchmark regression model used in this section consists of nine explanatory variables. To assess the presence of multicollinearity, we examine the variance inflation factor (VIF) value. A VIF value of 10 or less indicates no severe multicollinearity. The test results of multicollinearity for the variables are presented in Table 2. The findings reveal that the largest VIF value among the explanatory variables is only 3.310, which is significantly below 10. Hence, the model does not suffer from any significant multicollinearity issues.

Stationarity test

This study utilizes panel data covering the period from 1997 to 2021, resulting in a time span of 25 years. To ensure accurate estimation results and prevent biased outcomes due to spurious regression, we performed unit root tests on the data using HT, IPS, and ADF methods. The obtained test results are summarized below:

Based on the findings presented in Table 3, it is evident that all variables exhibit first-order single integration and possess good stationarity, as confirmed by the IPS test, HT test, and ADF test after first-order differencing. Following this, the Kao test method was employed to assess cointegration, and the results revealed a significant cointegration relationship between the dependent and independent variables.

Empirical test

Heterogeneous impact of environmental regulation policy instruments on industrial green and low-carbon transformation

Table 4 presents the findings concerning the influence of environmental regulation policy instruments on China’s industrial green and low-carbon transformation. The model setting test indicates that the p values of the AR (2) and Sargan tests are both greater than 0.1, suggesting that there is no second-difference autocorrelation in the disturbance term of the system GMM model at the 10% significance level. Consequently, the instrumental variable used is valid, and the dynamic panel model based on the system GMM yields reasonable regression results.

In Column (1), the estimated results after introducing the quadratic term of command-type environmental regulation show that the primary term of command-type environmental regulation is positively significant. Moreover, the coefficient of the quadratic term is negatively significant at the 1% level, indicating a significant inverted U-shaped relationship between command-and-control environmental regulation and industrial green and low-carbon transformation. Initially, command-type environmental regulation promoted industrial green and low-carbon transformation. However, beyond a certain intensity threshold, it inhibits the transformation. This result is also consistent with some findings in the existing literature23,25,71. The utest command is used for verification. According to the results of the utest command, the slope of the relationship between command-type environmental regulation and industrial green and low-carbon transformation is first positive (0.0286, p < 0.01) and then negative (–0.0494, p < 0.01), and the 95% Fieller interval is [6.5900, 9.2363]. However, the extreme point of command-type environmental regulation is 7.9092, which is just within the interval. Moreover, the p-value of the overall test of the U-shaped relationship is 0.0000 < 0.01, so the null hypothesis is rejected. The above results suggest that there is an inverted U-shaped relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable. These results support Hypothesis 1 of this paper, indicating the validity of the inverted U-shaped relationship between command-type environmental regulation and industrial green and low-carbon transformation.

In Column (2), the system GMM estimation result is presented after the introduction of the quadratic term of investment-type environmental regulation. The results show that the primary term of investment-type environmental regulation is positive and significant and that the coefficient of the quadratic term is negative and statistically significant at the 1% level, which indicates that there is a significant inverted U-shaped relationship between investment-type environmental regulation and industrial green and low-carbon transformation. When the intensity of investment-type environmental regulation is low and has not yet reached the inflection point, it points out the direction for enterprises to carry out green R&D activities, reduces the risk and adjustment cost caused by the uncertainty of green innovation, thus making the output such as green patents continue to increase and promoting green and low-carbon transformation. When the level of investment-type environmental regulation continues to improve and crosses the inflection point, the government’s investment in industrial pollution control is too high, which is easy to cause enterprises to rely on the government’s investment in industrial pollution control, lack independent innovation strategy, and blindly carry out green R&D activities, thus causing resource redundancy and reducing the efficiency of enterprises’ green technology R&D. At this time, investment-type environmental regulation has a negative impact on green and low-carbon transformation6,7,72. Moreover, the utest command is used to verify the robustness of the inverted U-shaped relationship between investment-type environmental regulation and industrial green and low-carbon transformation. According to the results of the utest command, the slope of the relationship between investment-type environmental regulation and industrial green and low-carbon transformation is first positive (0.0655, p < 0.01) and then negative (–0.0169, p < 0.01), and the 95% Fieller interval is [4.6691, 11.8609]. The extreme point of investment-type environmental regulation is 4.9372, which is just within the interval. Moreover, the p-value of the overall test of the U-shaped relationship is 0.0000 < 0.01, so the null hypothesis is rejected. Based on the above results, there is an inverted U-shaped relationship between investment-type environmental regulation and industrial green and low-carbon transformation. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 of this paper is also verified.

Moving to Column (3), the estimated results are presented after introducing the quadratic term of expense-type environmental regulation. The results show that the coefficient of the first-order term of Expense-type environmental regulation is negative, whereas the coefficient of the quadratic term is positive, indicating that there is a U-shaped relationship between Expense-type environmental regulation and industrial green and low-carbon transformation. Among them, the inflection point value is 10.167. It can be seen from the sample data that the intensity of fee-based environmental regulation in most provinces has not crossed the inflection point value, that is to say, most provinces have policy failures such as crowding out enterprise R&D capital investment due to the collection of pollution charge, and the cost effect of green innovation appears, while the compensation effect of green innovation has a time lag. As a result, the uncertainty of R&D resource supply increases, innovation output such as patents decreases, and industrial green and low-carbon transformation is slow. To verify the robustness of the “U” shaped relationship between Expense-type environmental regulation and industrial green and low-carbon transformation, the utest command is used for verification. According to the results of the utest command, the slope of the relationship between Expense-type environmental regulation and industrial green and low-carbon transformation is first negative (–0.1815, p < 0.01) and then positive (0.1497, p < 0.01), and the 95% Fieller interval is [6.6476, 17.1842]. The extreme point of Expense-type environmental regulation is 11.3097, which is just within the interval. Moreover, the p-value of the overall test of the U-shaped relationship is 0.0000 < 0.01, so the null hypothesis is rejected. On the basis of the above results, there is a U-shaped relationship between Expense-type environmental regulation and industrial green and low-carbon transformation. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 of this paper is also verified.

The regression results in Column (1) were selected for analysis, as there were no significant differences in the coefficients or significance of the control variables. The coefficient of R&D investment was found to be positive and statistically significant at the 1% level, suggesting that an increase in R&D investment can foster industrial green and low-carbon transformation. Similarly, the coefficient of foreign investment was positive and significant at the 1% level, indicating that foreign direct investment contributes to technology spillover effects and facilitates industrial green and low-carbon transformation. Moreover, the coefficient of human capital was positive and significant at the 1% level, indicating that an improvement in the level of human capital supports industrial green and low-carbon transformation. Furthermore, the coefficient of the urbanization level was positive and significant at the 1% level, which can be attributed to the better quality of supporting hospitals and schools in more urbanized areas, attracting a skilled workforce and fostering green and low-carbon transformation in industries. Conversely, the coefficient of the industrial structure was negative and significant at the 1% level, suggesting that an increase in the output value of tertiary industry promoted the green and low-carbon transformation of industries.

Robustness test

To ensure the reliability and consistency of the estimation results, this study uses four methods to conduct robustness tests.

-

(1)

Increase the sample volume.

To ensure the robustness of the estimated results of command-type environmental regulation on industrial green and low-carbon transformation, referring to the method of He73, this section conducts a robustness test by expanding the sample to prefecture-level cities. Specifically, the data of 269 prefecture-level cities in China from 1997 to 2021 are used for regression analysis, in which the measurement methods of industrial green and low-carbon transformation and environmental regulation tools are consistent with the provincial data. The regression results are shown in Table 5. Columns (1) and (2) show the results of the command-type environmental regulation, columns (3) and (4) show the results of the investment-type environmental regulation, and columns (5) and (6) show the results of the expense-type environmental regulation. The results show that the significance of Table 6 is basically consistent with the coefficients and significance results of the variables shown in Tables 4 and 5, indicating that the regression results are robust.

Table 5 Robustness test of expanded sample size. Table 6 Robustness test of replacing the explained variable. -

(2)

Replacing the explained variable.

In accordance with the methods of the IPCC (2006), CO2 is recalculated according to the relevant data disclosed in the China Energy Statistical Yearbook; then, the EBM model and GML index are used to measure the industrial green and low-carbon total factor productivity, and the new industrial green and low-carbon transformation index (lnLGL2) is obtained via accumulation. It is used as a proxy variable for industrial green and low-carbon transformation for regression, and the relevant results are shown in Table 6. Columns (1) and (2) present the regression results for command-type environmental regulation, columns (3) and (4) present the regression results for investment-type environmental regulation, and columns (5) and (6) present the regression results for expense-type environmental regulation. The results show that the significance of Table 8 is basically consistent with the coefficients and significance results of the variables of concern in Tables 3 and 4, which proves that the regression results are robust74.

-

(3)

Lags of one and three periods for environmental regulation instruments.

Referring to the method of Yu et al.75, we further investigate the lagged effect of command-type environmental regulation on industrial green and low-carbon transformation by one-period lagged (L.Lcer) and three-period lagged (L3.lncer) regression of the core explained variables. The lagged variable is not correlated with the error term in the current period, so the effect of the current period can be excluded to some extent and the endogeneity problem can be alleviated. At the same time, lagged variables can also capture the dynamic effects and long-term relationships of economic variables. The detailed regression results are shown in Table 7. Columns (1) and (2) present the regression results for command-type environmental regulation, columns (3) and (4) present the regression results for investment-type environmental regulation, and columns (5) and (6) present the regression results for expense-type environmental regulation. The results show that the coefficients of the primary term and quadratic term of the one-period and three-period lags of command-type environmental regulation are consistent with the results in Tables 4, 5 and 6 above, which proves that the regression results are robust.

Table 7 Robustness test of the lag period of command environmental regulation. -

(4)

Endogeneity tests for two-way causality.

The previous empirical results show that the effect of environmental regulation policies on China’s industrial green and low-carbon transformation is nonlinear. Therefore, when selecting the instrumental variable method, the two-stage residual input method (2SRI), which is more suitable for nonlinear model estimation, should be adopted.

Referring to the study of Wang et al.55, the air circulation coefficient is selected as the instrumental variable of environmental regulation. The calculation of air circulation coefficient refers to Nasution (2015), which is measured by the product of wind speed and boundary layer height76. Therefore, the size of the regional air circulation coefficient mainly depends on natural phenomena such as climatic conditions, which meets the exogeneity requirement of instrumental variables. This treatment method can overcome the endogeneity problem caused by the existence of reverse causality to a certain extent. The results show that the coefficients of the primary term and quadratic term of the one-period and three-period lags of command-type environmental regulation are consistent with the results in Tables 4, 5 and 6 above, which proves that the regression results are robust (Table 8).

Table 8 Endogeneity tests for two-way causality.

Test of coupling effect of environmental regulation policy instruments on industrial green and low-carbon transformation

In Table 9, columns (1), (2), and (3) report the regression results of the coupling coordination degree of command-type environmental regulation and investment-type environmental regulation, command-type environmental regulation and fee-based environmental regulation, and investment-type environmental regulation and fee-based environmental regulation, respectively. Columns (4), (5), and (6) present the regression results of combining the degree of coupling coordination; Column (7) presents the regression results of the degree of coupling coordination of the three formal environmental regulations.

In the regression results of Column (1), the coefficient of the coupling coordination degree of command-type environmental regulation and investment environmental regulation is positive and significant, which indicates that the collocated use of command-type environmental regulation and investment environmental regulation can promote industrial green and low-carbon transformation. The possible reason for this result is that the use of command-type environmental regulation combined with investment-type environmental regulation not only improves the environmental standard, but also effectively alleviates the situation of capital crowding out by enterprises and weakens the possible speculation behavior of enterprises, thus promoting the green technology innovation of enterprises and realizing the green and low-carbon transformation of industry.

In the regression results in Column (2), the coefficient of the coupling coordination degree of command-type environmental regulation and fee-based environmental regulation is positive, which indicates that the collocated use of command-type environmental regulation and fee-based environmental regulation can promote industrial green and low-carbon transformation because the collocated use of command-type environmental regulation and fee-based environmental regulation will integrate the institutional and flexibility of the two. This is more conducive to promoting green and low-carbon industrial transformation. This result is also consistent with the previous theoretical analysis.

In the regression results of Column (3), the coefficient of the coupling coordination degree of investment-type environmental regulation and expense-based environmental regulation fails to pass the significance test. The possible reason is that the degree of current coupling and coordination of investment-type environmental regulation and expense-based environmental regulation is not high, which prevents them from playing a better or worse role in promoting industrial green and low-carbon transformation.

Combined with the analysis of the regression results in columns (4) to (6), after the coupling and coordination degrees between the three formal environmental regulations are combined, the coupling and coordination degrees of command-type environmental regulation and investment-type environmental regulation in columns (4) to (6) are still positive and significant at the statistical level of 1%. The degree of coupling coordination between command-type environmental regulation and fee-based environmental regulation is significantly positive, whereas the degree of coupling coordination between investment-type environmental regulation and fee-based environmental regulation is not significant.

Column (7) reports the regression results with the coupling synergy degree of the three formal environmental regulations added. Therefore, when using environmental regulation tools, the government should pay attention to the collocated use of environmental regulation tools, such as the collocated use of command-type environmental regulation and investment-type environmental regulation, command-type environmental regulation and expense-type environmental regulation, and the coordinated use of the three environmental regulation policy tools can help environmental regulation play a better role.

Further research

The theoretical examination discussed earlier indicates that command-type environmental regulations influence industrial green and low-carbon transformations via the resource crowding out effect and the innovation compensation effect. Similarly, investment-type environmental regulations impact these transformations through the resource compensation effect and the crowding out effect, while expense-type environmental regulations exert influence through the crowding out effect and the incentive effect. A notable observation is that all these environmental regulation tools either promote or inhibit industrial green and low-carbon transformations by impacting the progress of enterprises’ green technology. According to the endogenous growth theory, developing countries can achieve technological progress not only through independent R&D but also via technology import77. This raises the question: do environmental regulation policy tools affect industrial green and low-carbon transformation through both of these technological innovation pathways? To address this, models (7) to (9) were devised, drawing upon the stepwise regression method for testing mediating effects as illustrated in the studies of Baron and Kenn78. This investigation seeks to understand the influence and underlying mechanisms of environmental regulation policy tools on industrial green and low-carbon transformation, considering both independent R&D and technology import aspects.

The mediating variable in this context is the technological innovation path PTEit, encompassing both independent R&D (rd) and technology import (ti). When considering independent R&D, internal R&D expenditure is converted into R&D capital stock using the perpetual inventory method. This is then expressed as the ratio of R&D capital stock to the total industrial output value to gauge independent R&D. On the other hand, technology import comprises both direct technology import expenditure and foreign direct investment. These are quantified by the expenditure allocated to technology import and the share of foreign capital in GDP. The control variables taken into account include human capital, urbanization rate, industrial structure, and trade openness, with their definitions and measurement methods aligning with those previously mentioned. Model (9) illustrates the overarching influence of environmental regulation policy tools on industrial green and low-carbon transformation, with the coefficient α1 indicating the magnitude of this total effect. In Model (10), the coefficient β1 shows the influence of environmental regulation policy instruments on the technological innovation pathway. The product β1γ2 of γ2 from Model (11) and the coefficient β1 from Model (10) represents the mediating effect of the technological innovation path. In essence, it captures how environmental regulation policy instruments impact industrial green and low-carbon transformation via the technological innovation path.

Independent research and development

In Table 10, Columns (1)–(3), (4)–(6), and (7)–(9) present the test results of the mediating effects of command-based environmental regulation, investment-type environmental regulation, and fee-based environmental regulation, respectively.

The test results in Column (1) show that at the significance level of 1%, command-type environmental regulation can promote industrial green and low-carbon transformation. The test results in Column (2) show that the coefficient of command-type environmental regulation is positive at the significance level of 1%, indicating that command-type environmental regulation promotes independent innovation. This conclusion is also supported by some literature79,80. The test results in Column (3) show that the coefficient of command-type environmental regulation is significantly positive and that the coefficient of independent innovation is also positive. Therefore, the analysis of the regression results in columns (1)–(3) reveals that independent innovation plays a partial intermediary role in the process of command-type environmental regulation promoting industrial green and low-carbon transformation and that command-type environmental regulation has a significantly positive effect on industrial green and low-carbon transformation through independent innovation.

The test results in Column (4) show that the coefficient of investment-type environmental regulation is positive at the significance level of 1%, indicating that investment-type environmental regulation can promote industrial green and low-carbon transformation. The test results in Column (5) show that the coefficient of investment-type environmental regulation is positive and significant at the level of 1%, indicating that investment-type environmental regulation has a positive effect on the R&D investment of enterprises24. The test results in Column (6) show that the coefficient of investment-type environmental regulation is significantly positive and that the coefficient of independent innovation is positive and significant. Furthermore, the analysis of the regression results in columns (3)–(6) reveals that independent innovation plays a partial intermediary role in the process of investment-type environmental regulation promoting industrial green and low-carbon transformation and that investment-type environmental regulation plays a role in promoting industrial green and low-carbon transformation through independent innovation.

The test results in Column (7) show that at the significance level of 1%, Expense-type environmental regulation has an inhibitory effect on industrial green and low-carbon transformation. The test results in Column (8) show that the coefficient of Expense-type environmental regulation is negative at the significance level of 1%, indicating that the increase in Expense-type environmental regulation leads to a reduction in R&D investment81. The test results in Column (9) show that the coefficient of Expense-type environmental regulation is significantly negative, whereas the coefficient of independent innovation is positive and significant. Combined with the regression results in columns (7)–(9), independent innovation plays a partial intermediary role in the process of Expense-type environmental regulation promoting industrial green and low-carbon transformation. Expense-type environmental regulation inhibits industrial green and low-carbon transformation by reducing independent innovation.

Technology import

In Table 11, Columns (1)–(3), (4)–(6), and (7)–(9) present the test results of the mediating effects of command-based environmental regulation, investment-type environmental regulation, and fee-based environmental regulation, respectively.

Based on the regression results in columns (1) and (3), the coefficient of command-type environmental regulation in Column (1) is significantly positive at the 1% significance level, the coefficient of command-type environmental regulation in Column (2) is significantly positive, and the coefficients of command-type environmental regulation and technology import in Column (3) are both positive and significant. This shows that technology imports play a partial intermediary role in the process of command-type environmental regulation promoting industrial green and low-carbon transformation.

Combined with the regression results in columns (4)–(6), the coefficient of investment-type environmental regulation in Column (4) is positive and significant, the coefficient of investment-type environmental regulation in Column (5) is negative at the 10% level, the coefficient of investment-type environmental regulation in Column (6) is positive and significant, and the coefficient of technology import is significantly positive at the 1% level. This shows that an increase in investment-type environmental regulation will reduce technology imports, thus weakening the promotion effect on industrial green and low-carbon transformation.

In combination with the regression results in columns (7)–(9), the coefficient of Expense-type environmental regulation in Column (7) is negative and passes the significance test of 1%, the coefficient of Expense-type environmental regulation in Column (8) is negative and significant, the coefficient of Expense-type environmental regulation in Column (9) is negative at the significance level of 1%, and the coefficient of technology import is positive and significant. This means that an increase in the intensity of Expense-type environmental regulation reduces funds for technology imports and thus inhibits the green and low-carbon transformation of industry.

Conclusions

Green and low-carbon industrial transformation stands as a crucial pathway for China in realizing its “dual carbon” objectives. The environmental regulatory policy serves as the primary institutional mechanism to promote further this green and low-carbon industrial shift. Understanding its influence, along with its combined effects on the green and low-carbon transformation, is vital for achieving high-quality economic growth. By distinguishing between three categories of environmental regulatory instruments, specifically command-type, investment-type, and expense-type, this study theoretically evaluates and empirically investigates the influence and integrated effects of these instruments on industrial green and low-carbon transformation. This investigation uses an industrial panel dataset spanning 30 Chinese provinces from 1997 to 2021. The principal findings include:

-

(1)

Preliminary regression outcomes indicate that both command-type and investment-type environmental regulations influence industrial green and low-carbon transformations in an inverted U-shape pattern – first promoting and subsequently suppressing the transformation. Conversely, expense-type environmental regulation displays a U-shape trend: initially suppressing and then endorsing the transformation. This finding is similar to the conclusions in the existing literature that the impact of different environmental regulation policy instruments on green technology innovation shows U-shaped and inverted U-shaped characteristics25,31,75. Compared with previous scholars’ research, The conclusion of this paper reveals the impact of environmental regulation policy tools on the green and low-carbon transformation of specific industries, which not only provides a new perspective for us to deeply understand the relationship between environmental regulation policy tools and industrial green development, but also provides important theoretical basis and practical guidance for the formulation of more scientific and appropriate environmental regulation policies.

-

(2)

The regression results of national data show that the coupling synergy coefficient of command-type environmental regulation and investment-type environmental regulation is positive, the coupling synergy coefficient of command-type environmental regulation and expense-type environmental regulation is positive, and the coupling synergy coefficient of expense-type environmental regulation and investment-type environmental regulation is not significant. The coefficient of coupling coordination degree of command-type, investment-type and expense-type environmental regulation is positive and significant. Previous studies have primarily focused on the impact of a single environmental regulation tool on green total factor productivity, industrial green transformation, and low-carbon transformation1,4,10. Building on this foundation, the present study delves deeper by emphasizing the synergistic coupling effects between different environmental regulation tools. The findings not only enrich the research content in the field of environmental regulation but also provide robust empirical support for formulating more comprehensive and coordinated environmental regulation policies.

-

(3)